Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

43221317

Hochgeladen von

Thuy HoangOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

43221317

Hochgeladen von

Thuy HoangCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

411 Corporate Governance: An International Review, 2009, 17(4): 411425

Business Group Afliation, Firm Governance, and Firm Performance: Evidence from China and India

Deeksha A. Singh* and Ajai S. Gaur

ABSTRACT Manuscript Type: Empirical Research Question/Issue: This study seeks to understand how business group afliation, within rm governance and external governance environment affect rm performance in emerging economies. We examine two aspects of within rm governance ownership concentration and board independence. Research Findings/Insights: Using archival data on the top 500 Indian and Chinese rms from multiple data sources for 2007, we found that group afliated rms performed worse than unafliated rms, and the negative relationship was stronger in the case of Indian rms than for Chinese rms. We also found that ownership concentration had a positive effect on rm performance, while board independence had a negative effect on rm performance. Further, we found that group afliation rm performance relationship in a given country context was moderated by ownership concentration. Theoretical/Academic Implications: This study utilizes an integration of agency theory with an institutional perspective, providing a more comprehensive framework to analyze the CG problems, particularly in the emerging economy rms. Empirically, our ndings support, as well as contradict, some of the conventional wisdom, and suggest useful avenues for future research. Practitioner/Policy Implications: This study shows that reforms in general and CG reforms in particular are effective in emerging economies, which is an encouraging sign for policy makers. However, our research also suggests that it may be time for India and China to stop the encouragement for the empire building through group formation in the corporate world. For practioners, our ndings suggest that rms need to balance the need for oversight with the need for advice, while selecting independent directors. Keywords: Corporate Governance, Ownership Concentration, Board Independence, China, India

INTRODUCTION

ith an increasing integration of world economies and the growth of large organizations, corporate governance (CG) has emerged as an important issue for scholars as well as managers all over the world. Using agency theory as the dominant theoretical paradigm, the extant literature has mainly focused on the efcacy of various governance mechanisms that protect the shareholders from self serving managers (Rajagopalan & Zhang, 2008). Much of this research is situated in the context of developed economies, where the external governance environment and institutions to support the internal rm governance are stable and well developed (Judge, Douglas, & Kutan, 2008).

*Address for correspondence: Department of Business Policy, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 117592. Tel: 1-757-401-5963; E-mail: deeksha@nus.edu.sg

While a focus on within rm governance mechanisms has advanced our understanding of the links between governance standards and rm performance, there is an increasing realization that the efcacy of within rm governance may be dependent on the quality of external governance and institutions (Judge et al., 2008). This issue is particularly important for emerging economies, which often lack the institutions needed to support efcient within rm governance (Peng, 2003). It is well documented that many emerging economies, such as India and China, do not have well developed external control mechanisms, such as a market for corporate control, merger, and acquisition laws, and efcient law enforcement (Khanna & Palepu, 2000a; Peng, 2003). This not only makes it more difcult to govern the organizations, but also makes standard CG practices less legitimate (Judge et al., 2008).

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd doi:10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00750.x

412

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The lack of external institutional support raises several theoretical and empirical questions that have not been examined in the extant literature. For example, the theoretical focus of much of the extant literature has been on agency theory, which focuses on the governance problems due to a conict of interest between owners and agents. While principal-agent conict is common for developed economies, emerging economies face a different type of agency problem, where majority shareholders, who are often owners, exploit the interests of minority shareholders (Claessens, Djankov, & Lang, 2000; Dharwadkar, George, & Brandes, 2000). Such a conict of interest between different groups of owners, known as principal-principal conict arises due to the lack of shareholder protection and enforcement mechanism (Dharwadkar et al., 2000). This necessitates that the agency centric view of corporate governance be suitably modied to incorporate the arguments from an institutional perspective. The unique context of emerging economies also raises important empirical questions, as the governance arrangements found in these countries are quite different from those found in developed countries. For example, rms often arrange themselves in the form of business groups through pyramidal ownership structures in countries that lack the institutions needed for efcient market based exchanges (Almedia & Wolfenzon, 2006; Khanna, 2000; La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 2000). Such governance arrangements may make traditional governance mechanisms, such as the presence of independent directors in the board redundant. The independent directors may come from sister rms of a group, and therefore may not be effective, and their role may be limited to satisfying the statutory requirements. While afliation to a business group itself may have a positive or negative impact on rm performance, depending on the level of institutional development in a country, within rm governance is likely to moderate the effect of group afliation. In this paper, we address the above-mentioned issues by using an integration of the agency theory with the institutional perspective. Specically, we investigate the relationship between group afliation, within rm governance and rm performance, and how these relationships are contingent on the country contexts. We investigate two aspects of within-rm governance presence of independent directors in the board and the ownership concentration. Further, we investigate how the within-rm governance moderates the effect of group afliation in a given country context for rm performance. In doing so, this paper contributes to the corporate governance literature by providing a more holistic theoretical framework, and empirical ndings in the context of two important emerging economies India and China. The rest of the paper is arranged as following. In the next section, we provide a background on the CG standards in India and China. We build on this discussion to develop our theoretical arguments. This is followed by a presentation of our sample, methodology, and results. Finally, we discuss our results, and provide avenues for future research in this area.

THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

Background: Corporate Governance in India and China

Good corporate governance practices are essential for the development of a market based economy and consequently, a prosperous society. In a historical analysis of the growth of different world economies, North and Thomas (1973) attributed the rise of Western economies to a better governance environment and to more developed institutions that support market based exchange. An advanced external governance environment helps in the development of sound corporate governance practices in rms (Judge et al., 2008). Emerging economies such as India and China have lagged in this aspect in comparison to their developed economy counterparts. In a ranking of 25 emerging markets, conducted by the Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia (Gill, 2001), India was ranked 6th while China was ranked 19th. Another report by Asian Corporate Governance Association (Gill & Allen, 2007) puts China towards the bottom among 11 Asian markets. While India is third place in this ranking, the report says that the CG standards in these countries are still quite low as compared to their developed economy counterparts. Since the overall institutional environment has a denite bearing on the CG standards in a country, we need to understand CG practices in view of the broader institutional characteristics. Tables 1 and 2 present the general economic reforms and CG specic reforms carried out in China and India respectively (Gaur, 2007). In the case of China, the economic reforms started in 1978 at a very modest level (Li, Park, & Li, 2004). However, it was not until 1993 that the rst important steps were taken to improve the CG standards. China passed the Company Law in 1993, which became effective in 1994. This was further modied in 1999. The Company Law provided the guidelines concerning the rights, responsibilities, and liabilities of different groups such as shareholders, board of directors, and managers. Further, in 1998, China enacted the Securities Law, to regulate the stock markets. The Securities Law stipulated strict prohibition of unfair practices such as market manipulation and insider trading. Even with these laws, China faced several corporate scandals, the biggest being a RMB 745 million fraud in a listed company named Ying Guang Xia in 2001. This prompted the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) to issue a Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies. This code species several requirements for listed companies, such as presence of independent directors in the boards, adherence to strict information disclosure norms, and equal status to minority shareholders. The objective of these reforms has been to establish CG standards similar to the US system. However, as is revealed in several CG rankings, China has a long way to go before its CG standards can come close to those of Western economies. Unlike China, India has been a slow starter in reforms, initiating the rst steps only in 1991, when it was forced to do so due to a severe balance of payment crisis. However, even before the economic reforms started in India, India had a ourishing stock market, and large private participation in

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GROUP AFFILIATION, FIRM GOVERNANCE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

413

TABLE 1 Institutional Reforms in China General economic reforms Time line Stage 1 (19781983) Key reforms Initiated during the third plenum of the 11th Chinese Communist Party Congress held in December 1978 Ideological shift from abolition of markets to accepting markets as secondary with planning being the primary tool of economic well being. Specic steps included: Agricultural reform by the introduction of household responsibility system, which made house holds residual claimant on the agricultural produce Gradual opening up of the economy beginning with Guangdong and Fujian provinces, and establishment of special economic zones, which were allowed to become market economies dominated by private ownership Partial scal decentralization, which encouraged some scal responsibility at the province level Reforms in SOEs Market liberalization through a dual track approach. SOEs could sell excess produce at market price after fullling the planned quota Introduction of contract responsibility system for SOE reform Financial reforms through bank decentralization Further opening up of the economy through coastal open cities, and development zones Entry of private and collective rms Objective was to transform China to a socialist market economic structure and build a rule-based system Unication of exchange rates and convertibility on current account Restructuring of tax and scal system Reorganization of the central bank Downsizing of government bureaucracy Privatization and restructuring of SOEs Constitutional amendment to allow for private ownership Corporate governance specic reforms Time line 1994 1998 1999 2002

Source: Gaur (2007).

Stage 2 (19841993)

Stage 3 (1994 onwards)

Key reforms Introduction of Chinas Company Law Introduction of Chinas Securities Law to regulate capital markets and trading activities The Company Law was amended Code of Corporate Governance for listed companies released

business activities. There were also explicit rules governing rm behavior, even though many of the rules may have been inadequate (RBI, 2001). As a result, Indian rms had a better exposure to CG standards than their counterparts in many other emerging economies (Rajagopalan & Zhang, 2008). The need to strengthen the CG standards was felt after the markets witnessed scandals soon after the liberalization policies were initiated in 1991. This led to the constitution of Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), which has since then become an independent regulator of capital

markets. SEBI instituted four committees over the years, headed by prominent industrialists, to suggest CG reforms for Indian rms. These committees have given recommendations on issues such as the composition of the board of directors, audit committee, shareholder rights, and board procedures. While following the American model of CG, SEBI has made sure that the reforms take into account the contingencies of the local environment. Several scholars suggest that the CG standards in India are as good as in many other developed countries, even though the enforcement

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

414

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

TABLE 2 Institutional Reforms in India General economic reforms Time line 1991 Key reforms Fiscal crisis Foreign exchange sufcient to support just two weeks of imports Pressure from IMF to start liberalization as a pre-condition to loans Realization on part of policy makers of the importance of liberalization Government initiated a limited liberalization initiative Reserve Bank of India (RBI) devalued the Indian rupee by 20 per cent Delicensing Number of industries reserved for public sector reduced from 17 to 8 Licensing system abolished except in 15 critical industries Eliminated the requirement of governments approval for expansion of large rms Foreign rms allowed to hold majority ownership in JVs Automatic approval for foreign investment up to 51 per cent in 35 industries 100 per cent ownership shares and full repatriation of prots in many industries for investments by NRIs Foreign institutional investors (FIIs) given permission to invest in all securities traded on the primary and secondary markets with certain restrictions Restrictions on the use of foreign loans abolished Foreign portfolio investors allowed to invest in listed companies Indian rupee made fully convertible on current account 100 per cent debt FIIs permitted, FIIs could buy corporate bonds, but not government bonds The maximum ownership limit of 24 per cent for all FIIs in a rm raised to 30. Further reforms in investment policies Upper limit of ownership by one FII in one rm raised form 5 per cent to 10 per cent FIIs allowed to operate in forward markets on a limited basis FIIs allowed to trade equity derivatives Requirement of having at least 50 investors for FIIs eased to 20 investors Further liberalization in the investment regime Maximum ownership limit by FIIs made 49 per cent and further raised to sectoral specic caps Corporate governance specic reforms Time line 1992 Key reforms Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) act passed by the parliament SEBI instituted as an independent regulator Over the years, SEBI instituted four committees (in 1996, 1998, 2000, and 2002) for CG reforms Government efforts to reform Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), the major stock exchange in India met with stiff resistance. Government instituted a new stock exchange, National Stock Exchange (NSE), as a competitor to BSE, establishing better practices and more standard corporate governance (BSE was an association of Brokers). Over time, this resulted in reforms in the BSE as well SEBI made as a single window approver for FIIs (earlier they had to seek approval from the federal bank also)

1992

1994 1996 1997 1998

1999 2000 onwards

1994

2003

Source: Gaur (2007).

mechanism may be relatively weaker (Rajagopalan & Zhang, 2008; Varma, 1997). The impact reforms have had on the business environment have become quite visible as reected in the business envi-

ronment ratings given by the World Competitiveness Yearbook (19972006). Table 3 presents ratings on some general reform parameters for China, India, and the US for the 10-year time period from 1997 to 2006. We included the US

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GROUP AFFILIATION, FIRM GOVERNANCE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

415

TABLE 3 Key Reform Indicators Reform indicators Government adapts policies to new economic realities Year 1997 2000 2003 2004 2005 2006 1997 2000 2003 2004 2005 2006 1997 2000 2003 2004 2005 2006 1997 2000 2003 2004 2005 2006 1997 2000 2003 2004 2005 2006 China 5.31 5.03 5.17 5.17 4.81 5.41 1.80 1.60 2.88 2.88 1.94 2.82 4.00 4.82 4.99 6.81 5.19 5.47 5.32 7.67 5.02 5.02 4.23 5.51 5.70 3.71 5.12 5.12 4.40 5.45 India 4.23 4.51 3.91 3.91 5.04 5.19 2.65 2.49 2.16 2.16 2.69 2.79 5.00 4.67 4.21 5.91 4.86 4.58 4.27 4.23 4.22 4.22 4.75 5.21 6.05 5.17 5.09 5.09 5.38 6.07 US 5.46 6.58 5.31 5.31 4.90 5.34 4.63 4.66 4.33 4.33 3.37 4.39 7.00 6.25 6.61 5.92 5.54 6.41 7.44 8.76 8.41 8.41 8.00 7.96 6.06 7.42 6.41 6.41 7.00 6.87

while those linking rm governance with rm performance primarily rely on agency theory.

Group Afliation and Firm Performance

Business groups are an important feature of many emerging economies. Khanna and Rivkin (2001:47) dene a business group as a set of rms which, though legally independent, are bound together by a constellation of formal and informal ties and are accustomed to taking coordinated action. Scholars have put forth several theoretical perspectives explaining the prevalence of business groups. These include a resource based view of business groups (Guilln, 2000), business groups as a response to market failure (Caves, 1989; Leff, 1976, 1978), institutional voids (Chang & Choi, 1988; Khanna & Palepu, 1997, 2000a, 2000b; Leff, 1978) and policy distortions (Ghemawat & Khanna, 1998); and business groups as maximizers of control through pyramidal ownership structures (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 1999). The dominant logic in explaining the presence of business groups in China and India is an institutional perspective. The institutional perspective suggests that business groups in China and India have thrived due to two main factors policy inducements, and institutional voids. In the case of China, groups emerged as a consequence of government policy of ownership reforms of state owned enterprises (SOEs). In 1987, the Chinese government started providing incentives for SOEs to form business groups. The State Administration of Industry and Commerce (SAIC) denes business groups as those in which the core company has a capital of at least 50 million Yuan, with at least ve afliated companies, whose combined capital should be greater than 100 million Yuan. The Chinese government selected some of the state owned business groups as national trial groups, whose job was to absorb the non-performing SOEs. Over time, business groups in China have come to be associated with prestige, even though there are several costs associated in managing a business group. Recognizing the reputation associated with being a business group, many entrepreneurs also formed their own business groups in China. At present, business groups in China contribute about 60 per cent of the industrial output (Yiu, Bruton, & Lu, 2005). In the case of India, the presence of business groups could be attributed to policy distortion as well as institutional voids (Kedia, Mukherjee, & Lahiri, 2007). After independence from the colonial rule in 1947, the Indian government indirectly forced rms to form business groups by imposing severe regulatory and bureaucratic hindrance to their growth. Some of the policy instruments that government used to control economic activities include the Industrial Policy Resolution (1956), Monopolies Inquiry Commission (1965), Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP, 1969), Industrial Licensing Policy Inquiry Committee (1969), and Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (1973) (see Majumdar, 2004, for details). Together, these policies created an excessively restricted environment for private businesses. Firms had to seek a host of regulatory clearances before they could start a new operation or even increase production capacity. In addition to several restrictions, there was a conspicuous

Bureaucracy does not hinder economic development

Anti-trust regulation

Intellectual property protection

Judiciary system efciency

Source: World Competitiveness Yearbook (19972006).

to provide a general sense of relative understanding of China and India. As can be seen from the table, both India and China have steadily improved their standings on key parameters, such as reducing bureaucratic hindrances, antitrust regulation (in the case of India), etc. While the business environment is still far from being close to what we observe in the Western economies, it is better than what it was in the early 1990s. An important feature of both Indian and Chinese economies has been a large presence of business groups in economic activities. We argue that business groups are not only an organizational form, but also a governance mechanism with positive as well as negative consequences. In the next section, we elaborate on the performance consequences of group afliation, along with two other rm level governance mechanisms ownership concentration and board independence. Our hypotheses linking group afliation with rm performance primarily rely on the institutional perspective,

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

416

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

absence of institutions needed for efcient functioning of product, labor, and capital markets. With explicit restrictions in the total capacity and size, and because of a lack of external institutions needed to support entrepreneurial acts, the only way rms could grow was by diversifying into areas wherever opportunities were available. By arranging rms in the form of a business group, entrepreneurs could make use of internal markets for capital, products, and labor. These things were not available to stand alone rms due to the lack of quality institutions that could support efcient capital, product and labor markets. According to the institutional perspective, business group afliation provides several benets for emerging economy rms. Business groups help rms circumvent the problems that arise due to inadequate institutional support as groups ll the institutional voids (Chang & Choi, 1988; Khanna & Palepu, 1997, 2000a, 2000b). Group afliation also provides an easier access to capital, raw materials, and markets for end products of at least some member rms. The overall size of the group allows for economies of scope in terms of umbrella branding of the afliated companies, research and development in the case of related businesses, and developing internal human resources that could be used across different afliated rms. Finally, in the case of countries such as China and India, groups generally enjoy a good reputation, and are able to derive benets through their connections with the government, which are not easily available to stand alone rms. Because of these benets, groups often indulge in a high level of unrelated diversication, and control the afliated rms through a complex, often family or state dominated, ownership structure. The complexity of the ownership arrangement in a business group poses unique governance challenges, and consequently costs of being afliated to a business group (Gaur & Kumar, 2009). For example, group afliated rms experience principal-principal agency problems that arise due to conict of interest between the controlling family shareholders and minority shareholders. Such conict may result in misallocation of resources across the group. The misallocation of resources could also be to maintain internal equity across the afliated rms. Groups may also indulge in tunneling resources from one rm to the other (Bertrand, Mehta, & Mullainathan, 2002; La Porta et al., 1999). Tunneling can take many forms such as intra-rm transactions at non-market rates, leasing of assets, and providing loans at non-market rates. In the extreme case, the group owner may decide to systematically transfer the assets of one of the rms, which may not t into the future scheme of things for the group, to other group afliated rms, and declare the rm as bankrupt in due course, or sell it off to potential buyers. At the same time, a group may have to absorb the losses of non-performing rms of the group. While such subsidization helps the unprotable ventures in sustaining their operations, it negatively affects the performance of the protable ones. The analysis of sources of benets and costs of group afliation suggests that benets primarily arise due to the context specic properties, and largely depend on the extent of inefciencies in the external governance environment. As the context changes and institutions develop to support

market-based exchanges, the benets are likely to decrease. In recent years, there has been a substantial improvement in the governance standards, and labor, capital, and product markets in India and China (Gaur, 2007), which has resulted in partial lling of the institutional voids, and thereby reducing the potential benets of group afliation. For example, in India, bank deposit rates fell from a high of 13 per cent in 1991 to 5.25 per cent in 2004, while the lending rates fell from a high of 19 per cent in 1991 to 10.25 per cent in 2004. Foreign investment inows during the same period increased from a miniscule base of US $133 million in 1992 to US $16,050 million in 2004. The transaction costs for transactions in Indian stock exchanges reduced from more than 4.75 per cent of the total transaction amount in 1994, to .60 per cent in 1999, which is close to the global best of .45 per cent. There have been several such improvements with respect to the labor and product markets in India (see Gaur, 2007 for details). While, China has been somewhat lagging behind India on the reform indices, it has also come a long way from a non-functional stock market in 1990 to the worlds fth largest stock exchange (Shanghai Stock Exchange) with a US $3.2 trillion market capitalization in 2007. Clearly, the institutional voids hypothesis (Khanna & Palepu, 2000a) would suggest that as the institutional voids disappear, the benets group afliated rms derive from such voids would also disappear. Consistent with this, several studies done in contexts with different levels of institutional development, and across different time periods have shown that the benets of group afliation decrease as the institutions develop (Gaur & Delios, 2006; Hoskisson, Johnson, Tihanyi, & White, 2005). Costs associated with group afliation on the other hand, arise due to the internal governance challenges and agency problems associated with managing a business group (Gaur & Kumar, 2009). Several of these costs, such as those arising due to the complexity in managing a diversied business portfolio may actually magnify as the environment changes, and the competition from independent, focused rms and foreign rms increases. Given the changes in the institutional environment in India and China, we expect that group afliation will no longer be benecial for rm performance in these economies. Accordingly, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 1a (H1a). Afliation to a business group will be negatively associated with rm performance in China and India. As discussed before, the institutional environment in China and India has some subtle differences. For example, there is more active, direct as well as indirect participation by the government in the case of China compared to India. Table 3 shows that China lags behind India on parameters such as bureaucratic hindrances, anti-trust regulations, and the efciency of the judicial system. As the business environment in India is more conducive for private sector activities than it is in China, group afliated rms in India enjoy fewer benets than their counterparts in China. As we elaborated upon earlier, business groups in China started as a tool for government intervention to reform SOEs and make them world class competitors (Keister, 2000). A key ingredient of reforms in China has been corporatization,

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GROUP AFFILIATION, FIRM GOVERNANCE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

417

rather than privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Keister, 2000; Li & Wong, 2003). The objective was to provide support to the SOEs so that they can stand on their own and compete against foreign and other private players. Several scholars have argued that the Chinese government policies are targeted at not allowing the private sector to play a major role in the economy (Qian, 1996; Xu & Wang, 1999). At the same time, the Chinese government encouraged formation of business groups for SOEs to ll the ownership voids created by the sudden withdrawal of direct supervision and control by the government (Li, 1997). In this sense, business groups in China essentially act as the owners of Chinese SOEs, although the ultimate control resides with the government. Chinese government has, from time to time, provided active support to business groups, and many of these organizations have indeed emerged as world class competitors. The situation in India had been quite different, where governments active participation in economic activities actually discouraged the formation of large organizations. The only way for Indian businesses to benet from government intervention was to somehow manipulate the government intervention to their advantage. While such interventions beneted some rms, they were harmful for others. In recent years, however, government intervention in economic activities is limited to providing support institutions for market-based exchanges. As a consequence, groups role as lling institutional voids has drastically reduced (Kedia et al., 2007). Moreover, the opportunities to benet from the governments intervention have been reduced, and competition from independent and foreign rms has increased signicantly (Gaur, 2007). As a net effect, we expect that group afliation will have a greater negative impact on the Indian rms than on the Chinese rms. Hypothesis 1b (H1b). Afliation to a business group will have a greater negative impact on the performance of the Indian rms than that of the Chinese rms.

Firm Governance and Firm Performance

Ownership Concentration. Research on ownership concentration and rm performance has a rich heritage (Morck, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1988; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997), with scholars investigating the effect of ownership concentration on performance of rms from both developed as well as emerging markets. Much of this literature has been developed based on agency theory and the Anglo-American model of CG (Varma, 1997). Even though increasing globalization is forcing the CG practices to converge towards the AngloAmerican model, the unique conditions in emerging economies demand investigations that take into account the effect of the local contingencies. Based on the Anglo-American model of CG, scholars have argued that a greater ownership in the hands of a few owners helps in disciplining the erring managers, even when there may not be enough legal protection (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). A greater ownership provides the needed incentive to actively engage in monitoring the actions of the managers, collect necessary information, and take actions when needed to protect self-interest. A greater ownership

also provides enough voting rights to oust the management, or even to take an outright control of the rm (Shleifer & Vishny, 1986). In a survey of corporate governance practices around the world, Shleifer and Vishny (1997) found that ownership concentration beneted rms in several ways in countries such as Germany, Japan, and the US. However, they also found that ownership concentration does not automatically provide controlling rights to owners and managers in countries such as Russia, and the effectivness of concentration as a governance mechanism depends on the extent of legal protection for the voting rights of the shareholders. In the case of emerging economies such as India and China, a higher ownership concentration may substitute for the absence of strong external governance (Dharwadkar et al., 2000). In the case of India, dominant owners often also work as managers, eliminating the principal-agency problem altogether (Carney, 2005; Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino, & Buchholtz, 2001). In the case of China, the state often works as dominant owner. Liu and Sun (2005) examined the ownership structure of the Chinese listed rms and found that 84 per cent of the rms had the state as the ultimate owner. A high ownership concentration in such cases may be benecial due to several reasons. First, a high ownership concentration minimizes the traditional agency problems related to managerial entrenchment (Walsh & Seward, 1990). Second, a high ownership concentration helps in more efcient and faster decision making, which is very important to remain competitive in the fast changing environment in emerging economies (Carney, 2005). Finally, high ownership concentration means that owners will be actively involved in making sure that their investments are successful (Gaur, 2007). In the case of emerging economies, such as China and India, owners often bring a lot of political and social capital. Such political and social capital helps emerging market rms secure easier access to raw materials and nancing, as well as government contracts. While providing several benets, a high ownership concentration, especially in the hands of a family or state also causes a few problems. Owners with a high ownership concentration may exploit the minority shareholders, and pursue actions that are not always in the best interest of the rm (Bertrand et al., 2002). A dominant owner may also exploit the minority owners using pyramidal ownership structures or complex interlocking ownership arrangements (Almedia & Wolfenzon, 2006). In the case of state owned rms, a high ownership concentration increases the instances of perquisite consumption by the salaried managers. Perquisite consumption relates to employees attempts to enhance their non-salary income and other on-job consumptions, such as wasteful expenditure on travel (Gedajlovic & Shapiro, 1998). Dharwadkar et al. (2000) attribute these agency problems to weak external governance mechanisms prevailing in emerging economies. The above discussion suggests that a greater ownership concentration in the case of Indian and Chinese rms has both positive and negative consequences. The positive effects arise as greater ownership concentration alleviates the traditional agency problems such as expropriation hazards (Schulze et al., 2001). The negative effects arise due to weak external governance environment (Dharwadkar

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

418

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

et al., 2000), and the associated principal-principal agency problems. However, as discussed before, there have been substantial improvements in the governance environment in both China and India in recent years. For example, both India and China have developed a corporate governance code for listed rms, in line with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of the US. There have also been efforts to protect the rights of the minority shareholders. In the case of China, if the controlling shareholder owns more than a 30 per cent stake, the rm must adapt a cumulative voting mechanism to give appropriate consideration to the voting rights of minority shareholders (Rajagopalan & Zhang, 2008). In addition, at least one-third of the shareholders must be independent and rms must fully disclose the related party transactions. Similar to China, Indian corporate governance code is also targeted at securing the minority rights and ensuring that the controlling stakeholders are not making undue advantage of their position for personal gains. As a result of these corporate governance specic reforms, the negative effects of high ownership concentration are likely to get reduced. Consequently, we expect the positive effects of ownership concentration to outweigh the negative effects. Accordingly, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 2a (H2a). Ownership concentration will be positively associated with rm performance in China and India. Even with many similarities in the institutional environment in India and China, we expect that the costs and benets associated with a high ownership concentration will differ for Indian and Chinese rms. In the case of India, there has been a very active participation of retail and institutional investors in recent years. This can be gauged by the fact that the Bombay Stock Index, which is the index of the main stock exchange in India, has increased more than 1,600 per cent from 1,000 in 1992 to close to 16,000 in 2007. This has been accompanied by improvements in investor protection and corporate governance laws, making it difcult for a majority owner to expropriate the rm value at the expense of minority owners. The improvement in the external governance environment means that the negative effects of ownership concentration are minimized, while the effectiveness of ownership concentration as a governance mechanism increases. As compared to India, the corporate governance laws and governance standards are not very strong in China in spite of the progress made in recent years (Rajagopalan & Zhang, 2008). The stock market in China is relatively new, and rms are still learning effective strategies for operating in a free market economy. With poorly functioning stock markets, ownership concentration as a governance mechanism is not as effective as it is in India. In fact, owners and/or managers in these rms are known to take actions that not only harm themselves, but also others around them in their pursuit of non-rationale goals (Jensen, 1998). As a result, we expect that ownership concentration is likely to be more benecial for the Indian rms than for the Chinese rms. Hypothesis 2b (H2b). Ownership concentration will have a greater positive impact on the performance of the Indian rms than that of the Chinese rms.

Board Independence. Board independence as a CG mechanism gained in prominence after the 2002 SarbanesOxley Act mandated the presence of independent directors on the boards of listed US companies. Following this other countries also mandated the use of independent directors on the boards, to strengthen the monitoring role of the boards. Scholars arguing in favor of board independence rely on the agency theory view point, which suggests that board members, who are free from the inuence of rm management, may be better able to monitor the actions of the management (Cadbury, 1992). Scholars arguing against board independence rely on the stewardship theory, which suggests that having more insiders on the boards provides a unied leadership and helps make more prudent decisions (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, 1997; Finkelstein & DAveni, 1994). The empirical evidence on the relationship between board independence and rm performance is mixed, with scholars reporting a negative (Boyd, 1995), positive (Rechner & Dalton, 1991), as well as no relationship (Daily & Dalton, 1997; Dalton, Daily, Johnson, & Ellstrand, 1999) between the two constructs. In a meta-analysis of 54 studies, Dalton et al. (1999) found no systematic relationship between board composition and rm performance. We argue that whether board independence is benecial or not depends on the function a board serves in a given context. Boards have two primary roles an oversight role and an advisory role. In the oversight role, board members are expected to mitigate the agency problems and protect the interests of the shareholders. In the advisory role, board members are expected to guide the rm in its vision and mission development as well as in strategy formulation. Board independence is important if a boards primary function is to oversee the rm management and alleviate the traditional agency problems. However, an independent board is likely to be less effective in an advisory role. Independent members are less aware of the internal functioning of the rm, its resources and capabilities, and the complexities associated with the functioning of the rm (Davis et al., 1997). A greater number of independent members also increase the chances of a conict within the board, and delay the decision making on key issues. As a result, independent members, though good from the point of view of oversight, may not be good from the point of view of an advisory role. We argue that in emerging economies such as India and China, the advisory role is likely to be more important than the oversight role due to several reasons. First, as argued before, the traditional agency problems related to the conict between owners and managers are less of a concern in emerging economies due to the unication of ownership and control (Dharwadkar et al., 2000). As the potential of conict between owners and managers reduces, so does the importance of boards oversight role. Second, owners and/or managers in emerging economy rms often view board independence as a mere statutory requirement and attempt to fulll it by appointing people who consider their role as ceremonial. The principle of board independence is thus followed only in letters and not in spirit. This problem is accentuated because of weak external governance, which allows rms to get away with loose adherence to rules and regulations about board independence. For example,

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GROUP AFFILIATION, FIRM GOVERNANCE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

419

business group afliated rms are known to employ people from other afliated companies in their boards. Third, even when the oversight role may be important, it is not easy for emerging economy rms to get the services of qualied independent directors because of the limited availability of such directors (Knowledge@Wharton, 2007). At the same time the advisory role is quite important for emerging economy rms as the rm management often lacks the requisite expertise needed for running the rm (Khanna & Palepu, 1999). With limited oversight needed, board members also consider advising as their main role. As a net result, we expect that in general, it may be more benecial for emerging economy rms to have less independent directors in the boards. Accordingly, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 3a (H3a). Board independence will be negatively associated with rm performance in China and India. We also expect country specic differences in different roles of a board. In the case of India, the unication of ownership and control is more common due to the prevalence of family managed rms and privately owned business groups (Gaur, 2007). As a result, boards may have only a limited oversight role, and the advisory role may be their main function. With an advisory role taking precedence over an oversight role, independent boards are likely to be harmful for Indian rms. On the other hand, in the case of China, an oversight role becomes more important due to the active participation of the state in business activities, and less transparent internal functioning of rms. The problem of perquisite consumption is particularly important for state owned rms and business groups as employees often indulge in corruption. Furthermore, the complex ownership arrangements in Chinese rms (Delios, Wu, & Zhou, 2006) necessitate that the board keeps an eye on the functioning of the management. As a result, board independence may still have some value in the case of Chinese rms. Accordingly, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 3b (H3b). Board independence will have a greater negative impact on the performance of the Indian rms than that of the Chinese rms.

a desired goal (Khanna & Palepu, 2000a). Such decision making is easier if the ownership is in the hands of a few, whose interests are aligned with the interests of the rms. Business group afliated rms in the case of India represent such a case as the fortunes of owners or families are directly linked with the performance of the rm. Carney (2005) suggests that ownership concentration in family owned business groups is a very effective governance mechanism for emerging economy rms. The scenario is different in the case of China as business groups in China are mostly state owned. A higher state ownership in business groups is not likely to have the same effect as a higher family or individual ownership (as is found in the case of Indian business groups). This is because unlike individual owners, the state does not always pursue prot maximization strategies. The state has many other objectives, such as societal welfare, equitable development, survival etc., which may take precedence over prot maximization (Menshikov, 1994). As a result a higher ownership concentration in the case of Chinese business groups may not be able to mitigate the negative consequences of group afliation. Accordingly, we propose the following three-way interaction hypothesis: Hypothesis 4a (H4a). The negative effect of group afliation on rm performance for the Indian rms will be reduced if there is a greater ownership concentration. Unlike ownership concentration, board independence, as a governance mechanism has a negative effect on emerging economy rms. In the case of Indian business groups, this negative effect may get amplied due to three reasons. First, for an effective functioning of afliated rms, an in-depth understanding of group-wide resources and capabilities is needed, which independent members may not possess. Second, afliated rms need to be very cohesive with each other, taking coordinated actions. Independent members may hinder such functioning of afliated rms as they may not be able to appreciate the value of coordinated actions (Davis et al., 1997). Finally, the importance of an advisory role over an oversight role requires that the board members do not unnecessarily interfere with the functioning of the group, and the board acts to assist the rm management, rather than contain it. More insiders in the board are likely to be helpful in this respect. In contrast to rms afliated with the Indian business groups, board independence in the case of rms afliated with the Chinese business groups may be benecial. Chinese business groups have evolved due to forced agglomeration of businesses by the state. Even in the case of privately and foreign owned business groups, the group formation has been due to active encouragement by the Chinese government. As a result, these afliated rms in China do not always have to take coordinated actions. In fact scholars have suggested the group formation by private rms in China may be only to conform to the mimetic pressures, than due to any economic rationale. As a consequence, the advisory role is further reduced for rms afliated with Chinese business groups. At the same time, the oversight role is accentuated to make sure that the managers in the afliated rms do not indulge in self-serving actions. Accordingly, we propose:

The Contingent Value of Firm Governance

As elaborated before, we expected that afliation with a business group will have a negative effect on rm performance. Further, we expected this negative effect to be stronger for the Indian rms than for the Chinese rms. In this section we discuss how two aspects of rm governance ownership concentration and board independence affect the group afliation, rm performance relationship in India and China. In doing so, we rely on an integration of agency theory with an institutional perspective to suggest that the costs and benets of group afliation are contingent on the type of within-rm governance. A higher ownership concentration minimizes the agency problems and enables the decision makers to make quick decisions. Given that the negative effects of group afliation primarily arise due to the governance challenges, and the complexities of managing a disparate set of businesses, cohesive actions by the afliated rms may be important to reach

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

420

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

Hypothesis 4b (H4b). The negative effect of group afliation on rm performance for the Indian rms will be increased if there are more independent members in the board. Being three-way interaction hypotheses, the previous two hypotheses include our arguments for China. We will elaborate on this when we discuss our results.

METHODS AND VARIABLES

Sample

We focused our study on China and India. We obtained a list of rms listed in the major stock exchanges in China and India from the 2008 edition of the OSIRIS database. The OSIRIS database has a comprehensive coverage of more than 55,000 rms in over 190 countries. It has a total of 1,701 Chinese listed rms and 2,957 Indian listed rms. We selected top 500 rms from both India and China, based on market capitalization at the end of 2007. We had to drop some rms for which we could not gather information on key independent variables. This resulted in a nal sample size of 813 rms, 400 of which were Indian, while 413 were Chinese.

study investigating the performance differential between rms, we included diversication as a control to account for the performance differential that can be attributed to diversication. We measured age as the number of years since foundation to 2007. Firm size was the natural logarithm of the market capitalization at the end of 2007. We measured the level of diversication by the number of subsidiaries in which the focal rm has some ownership. A better way would have been to nd a Herndhal like measure of diversication, which we could not due to data limitations. However, for a control variable, the number of afliates is a reasonable approximation. We measured board size by taking the natural logarithm of the total members in a board. Finally, country membership was an indicator variable, which took a value of one for Indian rms, and zero for the Chinese rms.

Modeling Procedure

We performed hierarchical moderated regression analysis to investigate the performance consequences of group afliation and within rm governance variables. Since our hypotheses require testing for two-way and three-way interactions, we developed the models in a hierarchical manner, introducing one interaction at a time. Such modelling procedure minimizes the problem of multicollinearity arising due to correlations between the main effect variables and their interaction terms (Wooldridge, 1999). In the models in which we tested for three-way interactions, we entered all the lower order interactions. We interpret the coefcient of main effects from the models in which interaction terms are not introduced.

Variables

Dependent Variable. We chose return on assets (ROA) as the dependent variables. ROA is one of the accounting based measures of performance, commonly used to measure rm performance. We also used return on equity (ROE) and return on sales (ROS) as alternate performance indicators, but found the results to be qualitatively similar. We obtained the data on ROA, ROE, and ROS from the OSIRIS database. Explanatory Variables. Business group afliation, ownership concentration, and board independence were the key explanatory variables. We measured group afliation by an indicator variable, which took a value of one, if the rm belonged to a business group, and zero otherwise. This is consistent with the conceptualization of group afliation in the extant literature (Khanna & Rivkin, 2001). We obtained information on the group afliation variable from the PROWESS database, which has been used extensively in research (e.g., Chacar & Vissa, 2005; Khanna & Palepu, 2000a). We measured ownership concentration by the percentage of ownership held by the largest shareholder. We obtained this information from the OSIRIS database for the Chinese rms and from the PROWESS database for the Indian rms. The ownership concentration variable was skewed, so we performed a logarithmic transformation on this variable. We measured board independence by taking a natural logarithm of the number of independent directors in the board. The OSIRIS database provides information on the board of directors, along with details such as if they are independent or not. Control Variables. We controlled for rm age, rm size, level of diversication, board size, and country membership. While rm age and rm size are standard controls in any

RESULTS

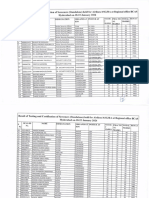

Table 4 provides the descriptive statistics and correlations. With 49 per cent Indian rms, the sample is evenly distributed between Indian and Chinese rms. Sixty-six per cent of the rms in the sample are business group afliated. Average age of the rms in the sample is 26 years. The average ownership concentration is 50 per cent, with the lowest and highest values being 7 per cent and 98 per cent respectively. The average size of the board is 8.37, with rms reporting as low as just two member boards and as high as 25 member boards. Board independence does not seem to be very common, with the average being only .31. Some rms do not have any independent members in their boards, while the maximum a rm has is seven. None of the correlations are high enough to warrant any problem of multicollinearity due to the main effect variables. The highest value of shared variance is only 42 per cent. Table 5 presents the results of regression analysis with return on assets (ROA) as the dependent variable. Model 1 has all the main effect variables along with the control variables. We introduced the interactions of group afliation, ownership concentration, and board independence with the country indicator variable in Models 2, 3, and 4. In Model 5, we introduced these interactions together. Models 6 and 7 have the three-way interactions, along with all the possible

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GROUP AFFILIATION, FIRM GOVERNANCE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

421

TABLE 4 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Variables 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Return on Assets Age Sizea Diversication Board size Board Independence Ownership Concentration 8. Group Afliation 9. Country (1 = India) Mean 6.64 26.03 1.06 7.77 8.37 .31 48.58 .66 .49 S.D. 8.61 24.57 .40 13.63 4.66 1.08 18.04 .47 .50 1 .18 -.02 -.17 .21 -.01 .11 -.17 .31 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-.26 -.33 .42 .10 .06 -.09 .58

.48 -.23 .00 .04 .14 -.50

-.42 -.12 -.22 .23 -.65

.47 .09 -.14 .65

.03 .01 .16

-.04 .12 -.23

Million US$. N = 813; Correlation >.10 and <-.10 in size are signicant at p = .05.

lower order interactions. We conducted F-tests on the signicance of the inclusion of each additional variable. As shown in Table 5, change in R-squared is signicant on inclusion of additional terms in Models 2, 5, and 6, conrming that the signicance of the additional interaction term is not spurious. H1a suggested that rms afliated with business groups will perform worse than the unafliated rms. The coefcient of group afliation variable is negative and signicant (Model 1: b = -1.94, p < .01), giving support to H1a. H1b suggested that the negative effect of group afliation will be stronger for Indian rms that for Chinese rms. A signicantly negative coefcient (Model 2: b = -2.94, p < .05) on the interaction of group afliation with the country indicator variables provides support for H1b. H2a suggested that ownership concentration will have a positive effect on rm performance. The coefcient of ownership concentration variable is positive and signicant (Model 1: b = 1.33, p < .10), giving support to H2a. H2b suggested that ownership concentration will have a greater positive impact for Indian rms than for Chinese rms. This hypothesis is not supported as the coefcient on the interaction term in Model 3 is insignicant. H3a suggested that board independence will have a negative effect on rm performance. The coefcient of the board independence variable is negative and signicant (Model 1: b = -1.32, p < .05). H3a is supported. H3b suggested that board independence will have a greater negative impact for Indian rms than for Chinese rms. This hypothesis is marginally supported as the coefcient on the interaction term in Model 4 is only marginally signicant (Model 4: b = -1.78, p < .10, one tailed). When we introduce all the two-way interaction terms together in Model 5, the coefcients and their signicance remain qualitatively the same. Next, we look at the three way interaction hypotheses. H4a proposed a three-way interaction between country indicator variable, group afliation, and ownership concentration, suggesting that the negative effect of group afliation for Indian rms will be reduced if these rms have a higher

ownership concentration. The coefcient on the three-way interaction term in Model 6 is positive and signicant (Model 6: b = 6.68, p < .05). Similar to H4a, H4b suggested that the negative effect of group afliation for Indian rms will be amplied if there are more independent members in the board of these rms. This hypothesis is not supported as the coefcient of the three-way interaction term in Model 7 is not signicant.

Robustness Tests

We tested the sensitivity of our relationships to alternate operationalizations of our key variables and on different subsamples, and found qualitatively similar results. We used return on equity (ROE) and return on sales (ROS) as alternate performance measures. In addition, we measured board independence by the ratio of independent to total directors. In all these cases, our estimation produced qualitatively similar results. Further, we created two subsamples one belonging to manufacturing rms and the other belonging to service sector rms. While all the hypothesized main effects and the two-way interaction effects were similar in sign and signicance to the results obtained in the full sample, the three way interaction effects were not signicant in the service sector subsample. This could be because of the small sample size of the service sector sub-sample.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We examined the performance consequences of business group afliation and within rm governance in India and China, which have a similar and yet distinct external governance environment. We looked at two aspects of within rm governance ownership concentration and board independence. We discussed the reform process and evolution of CG practices in India and China in recent years. Building on this, we developed our hypotheses utilizing an integration of agency theory with the institutional perspective.

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

422

Volume 17

TABLE 5 Regression Analysis (Dependent Variable: Return on Assets) Model 1 Beta .01 .25 .32 .85 1.05 .62 .73 .58 -.44 1.55 -1.78 1.25 .00 1.10*** .32 .67 8.50*** -.28 1.21 -1.30* -2.94* .01 .25 .32 .85 1.36 .94 .74 .58 1.25 .00 1.09*** .26 .65 8.15 -1.97** 1.47 -1.34* .01 .25 .32 .85 6.06 .62 .89 .58 .00 1.12*** .29 -.13 7.46*** -1.94** 1.19 .04 .01 .25 .32 1.02 1.26 .62 .70 1.12 .00 1.13*** .35 -.13 12.03* -.33 1.19 .01 -2.93* -.66 -1.74 .01 .25 .32 1.02 6.21 .94 .90 1.12 1.25 1.55 1.25 S.E. Beta S.E. Beta S.E. Beta S.E. Beta S.E. Beta .01 1.20*** .33 .03 26.14** 6.13 2.52 -.09 -28.65* -4.37 -1.49 -1.73 -.07 6.68** .143 .002 .149 .008*** Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 S.E. .01 .26 .32 1.02 9.95 7.93 1.90 1.43 12.9 2.58 1.28 2.12 1.11 3.36 .153 .004** Model 7 Beta .00 1.13*** .33 -.11 11.19 -3.52 .53 -.26 -2.81** -.47 -1.06 .84 .34 -1.00 .141 .146 .006** .141 .000 .149 .000 S.E. .01 .26 .32 1.02 6.46 6.21 1.60 1.97 1.41 1.64 2.20 1.66 2.05 2.45

Number 4

July 2009

Variables

Age Sizea Diversicationa Board Sizea India Group Afliation (GA) Ownership Conc. (OC)a Board Independence (BI)a GA India OC India BI India GA OC GA BI GA India OC GA India BI

.00 1.09*** .26 .66 6.46*** -1.94** 1.33 -1.32*

R Squared Change in R Squared

Logarithmic transformation performed. p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (all two-tailed).

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GROUP AFFILIATION, FIRM GOVERNANCE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

423

We proposed that in the changed economic environment in India and China, the costs of group afliation will outweigh the benets, making group afliation a costly governance mechanism. With respect to the within rm governance we hypothesized a positive effect of ownership concentration and a negative effect of board independence on rm performance. We proposed that within rm governance mechanisms will moderate the group afliation and rm performance relationships. Further, we expected the group afliation performance relationship in different country contexts to be contingent on the within rm governance. Our results largely support our hypotheses. We found that group afliated rms performed worse than unafliated rms, and the negative relationship was stronger in the case of Indian rms than Chinese rms. We also found that ownership concentration had a positive effect, while board independence had a negative effect on rm performance. We however, did not nd any country specic variation in the effect of these within rm governance variables. These insignicant results suggest that the relationship between withinrm governance and rm performance is not contingent on the country context in our two-country study. Further, we found that the group afliationrm performance relationship in a given country context was moderated by ownership concentration, but not by board independence. More specically, we found that the stronger negative effect of group afliation on Indian rms was abated if these rms had a higher ownership concentration. Since this is a three-way interaction hypothesis, this result also suggests that ownership concentration will not reduce the smaller negative effect of group afliation for Chinese rms. Future research should address the limitations of our study. Our data is cross-sectional in nature, which limits our ability to draw causal inferences. This study is based in Indian and Chinese contexts. Even though we controlled for country effects in all the models, it is possible that the country indicator variable may not capture all the differences between the two contexts. In addition, restriction to just two countries limits the generalizability of our ndings to other contexts. Just as we see that the ndings obtained in developed economy contexts may not be applicable to emerging economies, the ndings of this study may also be context specic. Future studies need to explore this relationship in other emerging economies. Finally, we use only accounting based measures of rm performance. Future studies could use Tobins Q or some other market based performance measures besides the accounting based performance measures. This study has important theoretical and empirical contributions. Our integration of agency theory with the institutional perspective provides a more comprehensive framework to analyze the CG problems, particularly in the emerging economy rms. Scholars have suggested that a more thorough understanding of agency problems can be gained by combining it with the institutional theory, and this paper is an effort in that direction (Eisenhardt, 1989). In addition, this paper highlights the nature of agency problems faced by rms in weak and changing institutional environments (Dharwadkar et al., 2000; Lemmon & Lins, 2003),

and how the external governance and within rm governance helps rms tackle these problems. More specically, we argue and show that neither an institutional, nor an agency logic can adequately capture the unique conditions faced by rms in emerging economies. On the one hand we nd that owner-manager arrangements in emerging economy rms alleviate the traditional agency problems. On the other hand we nd that the same ownermanager arrangement poses different types of agency problems due to weaker governance environments prevailing in emerging economies. As such, institutional perspective seems to be the dominant one for explaining rm strategy and performance in emerging economies, and we need to modify other theoretical lenses (e.g., agency theory in this study) to take into account the institutional characteristics in emerging economies. Empirically, our ndings support as well as contradict some of the conventional wisdom. Our results about the negative effect of group afliation are in contrast to the conventional wisdom that group afliation enhances rm performance (Chang & Choi, 1988; Khanna & Palepu, 1997, 2000a, 2000b). We do not disagree with the arguments that business groups ll the institutional voids in emerging economies, but we suggest that in the changed environment, costs of group afliation have become more than benets. Some other scholars also found support for this logic and showed that group afliated rms have lower protability than stand-alone rms, with the performance deteriorating more during later periods of institutional transition than the earlier periods (Gaur & Delios, 2006). It is plausible that the benets of group afliation may still be helpful for some other rm level outcomes such as sales growth, survival etc, and it would be interesting for future research to investigate just how does group afliation help emerging economy rms. Our results about the positive effect of ownership concentration conrm the conventional notion that ownership concentration helps mitigate the agency problems and improves rm performance (La Porta et al., 1999). However, the negative effect of board independence raises questions about the role of independent members in the boards of emerging economy rms. Extant research on board composition and rm performance has not been conclusive (Dalton et al., 1999). In fact, the critics of the Sarbanes-Oxley act argue that the requirement of independent members puts undue demand on rms to nd independent members and then manage smooth functioning of the board. There have been reports in the business press that rms are getting increasingly wary of the cumbersome requirements of the new CG practices, especially after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was implemented in the US and similar legislations followed in other countries. We agree that board independence may still be important from the point of view of making sure that rms do not indulge in unethical and illegal practices (Finkelstein & DAveni, 1994). However our results suggest that we should not perhaps view board independence in terms of performance gains, at least for the emerging economy rms. These results also have implications for policy makers and practioners. The negative effect we found on the group afliation variable can be attributed to the improvement in the

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

424

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

CG practices and rule based governance in India and China in recent years. This is an encouraging sign for the policy makers as the reforms initiated in India and China seem to be working at the micro level. However, this nding also suggests that it may be time for India and China to stop encouragement of empire building through group formation. For practioners, our ndings suggest that it may not be benecial for rms to blindly include many independent directors as a supervisory role is more important in the emerging economies. While selecting independent directors, rms need to balance the need for oversight with the need for advice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by an Asia Research Institute grant. We are thankful to the chief editor Bill Judge, special issue editors Shaomin Li and Anil Nair, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments during the review process.

REFERENCES

Almedia, H. & Wolfenzon, D. 2006. A theory of pyramidal ownership and family business groups. Journal of Finance, 61: 2637 2681. Bertrand, M., Mehta, P., & Mullainathan, S. 2002. Ferreting out tunneling: An application to indiAn business groups. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117: 121148. Boyd, B. K. 1995. CEO duality and rm performance: A contingency model. Strategic Management Journal, 16: 301312. Cadbury, A. 1992. Report of the committee on the nancial aspects of corporate governance. London: Gee Publishing. Carney, M. 2005. Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled rms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29: 249265. Caves, R. 1989. International Differences in Industrial organization. In R. Schmalensee & R. Willig (Eds.), Handbook of industrial organization, vol. 2: 12261249. Amsterdam: North-Holland. Chacar, A. & Vissa, B. 2005. Are emerging economies less efcient? Performance persistence and the impact of business group afliation. Strategic Management Journal, 26: 933946. Chang, S. J. & Choi, U. 1988. Strategy, structure, and performance of Korean business groups: A transaction cost approach. Journal of Industrial Economics, 37: 141158. Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. P. 2000. The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58: 81112. Daily, C. M. & Dalton, D. R. 1997. CEO and board chair roles held jointly or separately: Much ado about nothing? Academy of Management Executive, 11: 1120. Dalton, D. R., Daily, C. M., Johnson, J. L., & Ellstrand, A. E. 1999. Number of directors and nancial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 42: 674686. Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. 1997. Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22: 2047. Delios, A., Wu, Z. J., & Zhou, N. 2006. A new perspective on ownership identities in Chinas listed companies. Management and Organization Review, 2: 319343. Dharwadkar, R., George, G., & Brandes, P. 2000. Privatization in emerging economies: An agency theory perspective. Academy of Management Review, 25: 650669. Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14: 5774.

Finkelstein, S. & DAveni, R. A. 1994. CEO duality as a doubleedged sword: How boards of directors balance entrenchment avoidance and unity of command. Academy of Management, 37: 10791108. Gaur, A. S. 2007. Essays on strategic adaptation and rm performance during institutional transition. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, National University of Singapore. Gaur, A. S. & Delios, A. 2006. Business group afliation and rm performance during institutional transition. In K. M. Weaver (Ed.), Proceedings of the Sixty-sixth annual meeting of the Academy of Management (CD), ISSN 1543-8643. Gaur, A. S. & Kumar, V. 2009. International diversication, rm performance, and business group afliation: Empirical evidence from India. British Journal of Management, 20: 172 186. Gedajlovic, E. R. & Shapiro, D. M. 1998. Management and ownership effects: Evidence from ve countries. Strategic Management Journal, 19: 533553. Ghemawat, P. & Khanna, T. 1998. The nature of diversied business groups: A research design and two case studies. Journal of Industrial Economics, 46: 3561. Gill, A. 2001. Saint and sinners: Whos got religion? Hong Kong: CLSA Emerging Markets. Gill, A. & Allen, J. 2007 On a wing and a prayer: the greening of governance. Hong Kong: CLSA Asia-Pacic Markets. Guilln, M. F. 2000. Business groups in emerging economies: A resource-based view. Academy of Management Journal, 43: 362 380. Hoskisson, R. E., Johnson, R. A., Tihanyi, L., & White, R. E. 2005. Diversied business groups and corporate refocusing in emerging economies. Journal of Management, 31: 941965. Jensen, M. 1998. Self-interest, altruism, incentives, and agency. In M. Jensen (Ed.), Foundations of organizational strategy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Judge, W. Q., Douglas, T. J., & Kutan, A. M. 2008. Institutional antecedents of corporate governance legitimacy. Journal of Management, 34: 765785. Kedia, B., Mukherjee, D., & Lahiri, S. 2007. Indian business groups: Evolution and transformation. Asia Pacic Journal of Management, 23: 559577. Keister, L. 2000. Chinese business groups: The structure and impact of interrm relations during economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Khanna, T. 2000. Business groups and social welfare in emerging markets: Existing evidence and unanswered questions. European Economic Review, 44: 748761. Khanna, T. & Palepu, K. 1997. Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 75: 4151. Khanna, T. & Palepu, K. 1999. Emerging market business groups, foreign investors, and corporate governance. NBER working paper no. 6955. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, Cambridge, MA. Khanna, T. & Palepu, K. 2000a. Is group afliation protable in emerging markets? An analysis of diversied Indian business groups. Journal of Finance, 55: 867891. Khanna, T. & Palepu, K. 2000b. The future of business groups in emerging markets: Long-run evidence from Chile. Academy of Management Journal, 43: 268285. Khanna, T. & Rivkin, J. W. 2001. Estimating the performance effects of business groups in emerging markets. Strategic Management Journal, 22: 4574. Knowledge@Wharton. 2007. Corporate governance in India: Is an independent director a guardian or a burden? India Knowledge@ Wharton, February 8, 2007, Available from URL: http:// knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/india/article.cfm?articleid= 4157 (accessed on June 26, 2008).

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

GROUP AFFILIATION, FIRM GOVERNANCE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

425

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 1999. Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54: 471517. La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 2000. Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 58: 327. Leff, N. 1976. Capital markets in less developed countries: The group principle. In R. McKinnon (Ed.), Money and nance in economic growth and development. New York: Decker Press. Leff, N. 1978. Industrial organization and entrepreneurship in the developing countries: The economic groups. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 26: 661675. Lemmon, M. L. & Lins, K. V. 2003. Ownership structure, corporate governance, and rm value: Evidence from the East Asian nancial crisis. Journal of Finance, 58: 14451468. Li, M. & Wong, Y. 2003. Diversication and economic performance: An empirical assessment of Chinese rms. Asia Pacic Journal of Management, 20: 243265. Li, S., Park, S. H., & Li, S. 2004. The great leap forward: The transition from relation-based governance to rule-based governance. Organizational Dynamics, 33: 6378. Li, W. 1997. The impact of economic reform on the performance of Chinese state enterprises, 19801989. The Journal of Political Economy, 105: 10801106. Liu, G. S. & Sun, S. P. 2005. The class of shareholdings and its impacts on corporate performance: A case of state shareholding composition in Chinese publicly listed companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13: 4659. Majumdar, S. K. 2004. The hidden hand and the license Raj to an evaluation of the relationship between age and the growth of rms in India. Journal of Business Venturing, 19: 107126. Menshikov, S. 1994. The role of state enterprises in the transition from command to market economies. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 4: 289325. Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. 1988. Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical-analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 20: 293315. North, D. C. & Thomas, R. P. 1973. The rise of the western world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Peng, M. W. 2003. Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review, 28: 275296. Qian, Y. 1996. Enterprise reform in China: Agency problems and political control. Economics of Transition, 4: 427447. Rajagopalan, N. & Zhang, Y. 2008. Corporate governance reforms in

China and India: Challenges and opportunities. Business Horizons, 51: 5564. RBI. 2001. Corporate governance and international standards. http://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/docs/ 20023.doc (accessed on August 2, 2006). Rechner, P. L. & Dalton, D. R. 1991. CEO duality and organizational performance: A longitudinal analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 12: 155160. Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., Dino, R. N., & Buchholtz, A. K. 2001. Agency relationships in family rms: Theory and evidence. Organization Science, 12: 99116. Shleifer, A. & Vishny, R. W. 1986. Large shareholders and corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 294: 461491. Shleifer, A. & Vishny, R. W. 1997. A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52: 737783. Varma, J. R. (1997) Corporate governance in India: Disciplining the dominant shareholder. IIMB Management Review, 9: 5-18. Walsh, J. P. & Seward, J. K. 1990. On the efciency of internal and external corporate control mechanisms. Academy of Management Review, 15: 421458. Wooldridge, J. M. 1999. Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. New York: South Western College Publishing. World Competitiveness Yearbook (annual editions). 19972006. IMD World Competitiveness Center, Lausanne, Switzerland. Xu, X. & Wang, Y. 1999. Ownership structure and corporate governance in Chinese stock companies. China Economic Review, 10(1): 7598. Yiu, D., Bruton, G., & Lu, Y. 2005. Understanding business group performance in an emerging economy: Acquiring resources and capabilities in order to prosper. Journal of Management Studies, 42: 183296.

Deeksha A. Singh is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Business Policy at the National University of Singapore. Her research focuses on MNCs foreign investment strategies and strategy in emerging economy contexts. Ajai S. Gaur earned his Ph.D. at the National University of Singapore. He is an assistant professor in the Department of Management, College of Business and Public Administration, Old Dominion University. His research interests lie at the intersection of strategy and international management.

2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Volume 17

Number 4

July 2009