Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Cases Ii

Hochgeladen von

sebastinian_lawyers3827Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cases Ii

Hochgeladen von

sebastinian_lawyers3827Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

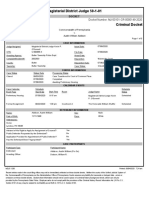

FIRST DIVISION [G.R. No. 146775. January 30, 2002] SAN MIGUEL CORPORATION, petitioner, vs.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS-FORMER THIRTEENTH DIVISION, HON. UNDERSECRETARY JOSE M. ESPAOL, JR., Hon. CRESENCIANO B. TRAJANO, and HON. REGIONAL DIRECTOR ALLAN M. MACARAYA, respondents. DECISION KAPUNAN, J.: Assailed in the petition before us are the decision, promulgated on 08 May 2000, and the resolution, promulgated on 18 October 2000, of the Court of Appeals in CA G.R. SP-53269. The facts of the case are as follows: On 17 October 1992, the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), Iligan District Office, conducted a routine inspection in the premises of San Miguel Corporation (SMC) in Sta. Filomena, Iligan City. In the course of the inspection, it was discovered that there was underpayment by SMC of regular Muslim holiday pay to its employees. DOLE sent a copy of the inspection result to SMC and it was received by and explained to its personnel officer Elena dela Puerta. SMC contested the findings and DOLE conducted summary hearings on 19 November 1992, 28 May 1993 and 4 and 5 October 1993. Still, SMC failed to submit proof that it was paying regular Muslim holiday pay to its employees. Hence, Alan M. Macaraya, Director IV of DOLE Iligan District Office issued a compliance order, dated 17 December 1993, directing SMC to consider Muslim holidays as regular holidays and to pay both its Muslim and non-Muslim employees holiday pay within thirty (30) days from the receipt of the order. SMC appealed to the DOLE main office in Manila but its appeal was dismissed for having been filed late. The dismissal of the appeal for late filing was later on reconsidered in the order of 17 July 1998 after it was found that the appeal was filed within the reglementary period.

However, the appeal was still dismissed for lack of merit and the order of Director Macaraya was affirmed. SMC went to this Court for relief via a petition for certiorari, which this Court referred to the Court of Appeals pursuant to St. Martin Funeral Homes vs. NLRC. The appellate court, in the now questioned decision, promulgated on 08 May 2000, ruled, as follows: WHEREFORE, the Order dated December 17, 1993 of Director Macaraya and Order dated July 17, 1998 of Undersecretary Espaol, Jr. is hereby MODIFIED with regards the payment of Muslim holiday pay from 200% to 150% of the employee's basic salary. Let this case be remanded to the Regional Director for the proper computation of the said holiday pay. SO ORDERED. Its motion for reconsideration having been denied for lack of merit, SMC filed a petition for certiorari before this Court, alleging that: PUBLIC RESPONDENTS SERIOUSLY ERRED AND COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION WHEN THEY GRANTED MUSLIM HOLIDAY PAY TO NON-MUSLIM EMPLOYEES OF SMC-ILICOCO AND ORDERING SMC TO PAY THE SAME RETROACTIVE FOR ONE (1) YEAR FROM THE DATE OF THE PROMULGATION OF THE COMPLIANCE ORDER ISSUED ON DECEMBER 17, 1993, IT BEING CONTRARY TO THE PROVISIONS, INTENT AND PURPOSE OF P.D. 1083 AND PREVAILING JURISPRUDENCE. THE ISSUANCE OF THE COMPLIANCE ORDER WAS TAINTED WITH GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN THAT SAN MIGUEL CORPORATION WAS NOT ACCORDED DUE PROCESS OF LAW; HENCE, THE ASSAILED COMPLIANCE ORDER AND ALL SUBSEQUENT ORDERS, DECISION AND RESOLUTION OF PUBLIC RESPONDENTS WERE ALL ISSUED WITH GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION AND ARE VOID AB INITIO. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION WHEN IT DECLARED THAT REGIONAL DIRECTOR MACARAYA, UNDERSECRETARY TRAJANO AND UNDERSECRETARY

1

ESPAOL, JR., WHO ALL LIKEWISE ACTED WITH GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION AND WITHOUT OR IN EXCESS OF THEIR JURISDICTION, HAVE JURISDICTION IN ISSUING THE ASSAILED COMPLIANCE ORDER AND SUBSEQUENT ORDERS, WHEN IN FACT THEY HAVE NO JURISDICTION OR HAS LOST JURISDICTION OVER THE HEREIN LABOR STANDARD CASE. At the outset, petitioner came to this Court via a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 instead of an appeal under Rule 45 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure. In National Irrigation Administration vs. Court of Appeals, the Court declared: x x x (S)ince the Court of Appeals had jurisdiction over the petition under Rule 65, any alleged errors committed by it in the exercise of its jurisdiction would be errors of judgment which are reviewable by timely appeal and not by a special civil action of certiorari. If the aggrieved party fails to do so within the reglementary period, and the decision accordingly becomes final and executory, he cannot avail himself of the writ of certiorari, his predicament being the effect of his deliberate inaction. The appeal from a final disposition of the Court of Appeals is a petition for review under Rule 45 and not a special civil action under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, now Rule 45 and Rule 65, respectively, of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure. Rule 45 is clear that decisions, final orders or resolutions of the Court of Appeals in any case, i.e., regardless of the nature of the action or proceeding involved, may be appealed to this Court by filing a petition for review, which would be but a continuation of the appellate process over the original case. Under Rule 45 the reglementary period to appeal is fifteen (15) days from notice of judgment or denial of motion for reconsideration. xxx For the writ of certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court to issue, a petitioner must show that he has no plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of law against its perceived grievance. A remedy is considered "plain, speedy and adequate" if it will promptly relieve the petitioner from the injurious effects of the judgment and the acts of the lower court or agency. In this case, appeal was not only available but also a speedy and adequate remedy.

Well-settled is the rule that certiorari cannot be availed of as a substitute for a lost appeal. For failure of petitioner to file a timely appeal, the questioned decision of the Court of Appeals had already become final and executory. In any event, the Court finds no reason to reverse the decision of the Court of Appeals. Muslim holidays are provided under Articles 169 and 170, Title I, Book V, of Presidential Decree No. 1083, otherwise known as the Code of Muslim Personal Laws, which states: Art. 169. Official Muslim holidays. - The following are hereby recognized as legal Muslim holidays: (a) Amun Jad d (New Year), which falls on the first day of the first lunar month of Muharram; (b) Maulid-un-Nab (Birthday of the Prophet Muhammad), which falls on the twelfth day of the third lunar month of Rabi-ul-Awwal; (c) Lailatul Isr Wal Mir j (Nocturnal Journey and Ascension of the Prophet Muhammad), which falls on the twenty-seventh day of the seventh lunar month of Rajab; (d) d-ul-Fitr (Hari Raya Puasa), which falls on the first day of the tenth lunar month of Shawwal, commemorating the end of the fasting season; and (e) d- l-Adh (Hari Raya Haji),which falls on the tenth day of the twelfth lunar month of Dh l-Hijja. Art. 170. Provinces and cities where officially observed. - (1) Muslim holidays shall be officially observed in the Provinces of Basilan, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, North Cotabato, Iligan, Marawi, Pagadian, and Zamboanga and in such other Muslim provinces and cities as may hereafter be created;

(2) Upon proclamation by the President of the Philippines, Muslim holidays may also be officially observed in other provinces and cities. The foregoing provisions should be read in conjunction with Article 94 of the Labor Code, which provides: Art. 94. Right to holiday pay. (a) Every worker shall be paid his regular daily wage during regular holidays, except in retail and service establishments regularly employing less than ten (10) workers; The employer may require an employee to work on any holiday but such employee shall be paid a compensation equivalent to twice his regular rate; x x x.

Considering that all private corporations, offices, agencies, and entities or establishments operating within the designated Muslim provinces and cities are required to observe Muslim holidays, both Muslim and Christians working within the Muslim areas may not report for work on the days designated by law as Muslim holidays. On the question regarding the jurisdiction of the Regional Director Allan M. Macaraya, Article 128, Section B of the Labor Code, as amended by Republic Act No. 7730, provides: Article 128. Visitorial and enforcement power. xxx

(b)

Petitioner asserts that Article 3(3) of Presidential Decree No. 1083 provides that (t)he provisions of this Code shall be applicable only to Muslims x x x. However, there should be no distinction between Muslims and non-Muslims as regards payment of benefits for Muslim holidays. The Court of Appeals did not err in sustaining Undersecretary Espaol who stated: Assuming arguendo that the respondents position is correct, then by the same token, Muslims throughout the Philippines are also not entitled to holiday pays on Christian holidays declared by law as regular holidays. We must remind the respondent-appellant that wages and other emoluments granted by law to the working man are determined on the basis of the criteria laid down by laws and certainly not on the basis of the workers faith or religion. At any rate, Article 3(3) of Presidential Decree No. 1083 also declares that x x x nothing herein shall be construed to operate to the prejudice of a non-Muslim. In addition, the 1999 Handbook on Workers Statutory Benefits, approved by then DOLE Secretary Bienvenido E. Laguesma on 14 December 1999 categorically stated:

(b) Notwithstanding the provisions of Article 129 and 217 of this Code to the contrary, and in cases where the relationship of employeremployee still exists, the Secretary of Labor and Employment or his duly authorized representatives shall have the power to issue compliance orders to give effect to the labor standards provisions of this Code and other labor legislation based on the findings of labor employment and enforcement officers or industrial safety engineers made in the course of the inspection. The Secretary or his duly authorized representative shall issue writs of execution to the appropriate authority for the enforcement of their orders, except in cases where the employer contests the findings of the labor employment and enforcement officer and raises issues supported by documentary proofs which were not considered in the course of inspection. xxx In the case before us, Regional Director Macaraya acted as the duly authorized representative of the Secretary of Labor and Employment and it was within his power to issue the compliance order to SMC. In addition, the Court agrees with the Solicitor General that the petitioner did not deny that it was not paying Muslim holiday pay to its non-Muslim employees. Indeed, petitioner merely contends that its non-Muslim employees are not entitled to Muslim holiday pay. Hence, the issue could be resolved even without documentary proofs. In any case, there was no indication that Regional Director Macaraya failed

3

to consider any documentary proof presented by SMC in the course of the inspection. Anent the allegation that petitioner was not accorded due process, we sustain the Court of Appeals in finding that SMC was furnished a copy of the inspection order and it was received by and explained to its Personnel Officer. Further, a series of summary hearings were conducted by DOLE on 19 November 1992, 28 May 1993 and 4 and 5 October 1993. Thus, SMC could not claim that it was not given an opportunity to defend itself. Finally, as regards the allegation that the issue on Muslim holiday pay was already resolved in NLRC CA No. M-000915-92 (Napoleon E. Fernan vs. San Miguel Corporation Beer Division and Leopoldo Zaldarriaga), the Court notes that the case was primarily for illegal dismissal and the claim for benefits was only incidental to the main case. In that case, the NLRC Cagayan de Oro City declared, in passing: We also deny the claims for Muslim holiday pay for lack of factual and legal basis. Muslim holidays are legally observed within the area of jurisdiction of the present Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), particularly in the provinces of Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi. It is only upon Presidential Proclamation that Muslim holidays may be officially observed outside the Autonomous Region and generally extends to Muslims to enable them the observe said holidays. The decision has no consequence to issues before us, and as aptly declared by Undersecretary Espaol, it can never be a benchmark nor a guideline to the present case x x x. WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the petition is DISMISSED. SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila THIRD DIVISION G.R. No. 144664 March 15, 2004

ASIAN TRANSMISSION CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. The Hon. COURT OF APPEALS, Thirteenth Division, HON. FROILAN M. BACUNGAN as Voluntary Arbitrator, KISHIN A. LALWANI, Union, Union representative to the Panel Arbitrators; BISIG NG ASIAN TRANSMISSION LABOR UNION (BATLU); HON. BIENVENIDO T. LAGUESMA in his capacity as Secretary of Labor and Employment; and DIRECTOR CHITA G. CILINDRO in her capacity as Director of Bureau of Working Conditions, respondents. DECISION CARPIO-MORALES, J.: Petitioner, Asian Transmission Corporation, seeks via petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the 1995 Rules of Civil Procedure the nullification of the March 28, 2000 Decision1 of the Court of Appeals denying its petition to annul 1) the March 11, 1993 "Explanatory Bulletin"2 of the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) entitled "Workers Entitlement to Holiday Pay on April 9, 1993, Araw ng Kagitingan and Good Friday", which bulletin the DOLE reproduced on January 23, 1998, 2) the July 31, 1998 Decision3 of the Panel of Voluntary Arbitrators ruling that the said explanatory bulletin applied as well to April 9, 1998, and 3) the September 18, 19984 Resolution of the Panel of Voluntary Arbitration denying its Motion for Reconsideration. The following facts, as found by the Court of Appeals, are undisputed: The Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), through Undersecretary Cresenciano B. Trajano, issued an Explanatory Bulletin dated March 11, 1993 wherein it clarified, inter alia, that employees

4

are entitled to 200% of their basic wage on April 9, 1993, whether unworked, which[,] apart from being Good Friday [and, therefore, a legal holiday], is also Araw ng Kagitingan [which is also a legal holiday]. The bulletin reads: "On the correct payment of holiday compensation on April 9, 1993 which apart from being Good Friday is also Araw ng Kagitingan, i.e., two regular holidays falling on the same day, this Department is of the view that the covered employees are entitled to at least two hundred percent (200%) of their basic wage even if said holiday is unworked. The first 100% represents the payment of holiday pay on April 9, 1993 as Good Friday and the second 100% is the payment of holiday pay for the same date as Araw ng Kagitingan. Said bulletin was reproduced on January 23, 1998, when April 9, 1998 was both Maundy Thursday and Araw ng Kagitingan x x x x Despite the explanatory bulletin, petitioner [Asian Transmission Corporation] opted to pay its daily paid employees only 100% of their basic pay on April 9, 1998. Respondent Bisig ng Asian Transmission Labor Union (BATLU) protested. In accordance with Step 6 of the grievance procedure of the Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) existing between petitioner and BATLU, the controversy was submitted for voluntary arbitration. x x x x On July 31, 1998, the Office of the Voluntary Arbitrator rendered a decision directing petitioner to pay its covered employees "200% and not just 100% of their regular daily wages for the unworked April 9, 1998 which covers two regular holidays, namely, Araw ng Kagitignan and Maundy Thursday." (Emphasis and underscoring supplied) Subject of interpretation in the case at bar is Article 94 of the Labor Code which reads: ART. 94. Right to holiday pay. - (a) Every worker shall be paid his regular daily wage during regular holidays, except in retail and service establishments regularly employing less than ten (10) workers;

(b) The employer may require an employee to work on any holiday but such employee shall be paid a compensation equivalent to twice his regular rate; and (c) As used in this Article, "holiday" includes: New Years Day, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, the ninth of April, the first of May, the twelfth of June, the fourth of July, the thirtieth of November, the twenty-fifth and thirtieth of December and the day designated by law for holding a general election, which was amended by Executive Order No. 203 issued on June 30, 1987, such that the regular holidays are now: 1. New Years Day January 1 2. Maundy Thursday Movable Date 3. Good Friday Movable Date 4. Araw ng Kagitingan April 9 (Bataan and Corregidor Day) 5. Labor Day May 1 6. Independence Day June 12 7. National Heroes Day Last Sunday of August 8. Bonifacio Day November 30 9. Christmas Day December 25 10. Rizal Day December 30 In deciding in favor of the Bisig ng Asian Transmission Labor Union (BATLU), the Voluntary Arbitrator held that Article 94 of the Labor Code provides for holiday pay for every regular holiday, the computation of which is determined by a legal formula which is not changed by the fact that there are two holidays falling on one day, like on April 9, 1998 when it was Araw ng Kagitingan and at the same time was Maundy Thursday; and that that the law, as amended, enumerates ten regular holidays for every year should not be interpreted as authorizing a reduction to nine the number of paid regular holidays "just because April 9 (Araw ng Kagitingan) in certain years, like 1993 and 1998, is also Holy Friday or Maundy Thursday." In the assailed decision, the Court of Appeals upheld the findings of the Voluntary Arbitrator, holding that the Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) between petitioner and BATLU, the law governing the relations between them, clearly recognizes their intent to consider Araw ng Kagitingan and Maundy Thursday, on whatever date they

5

may fall in any calendar year, as paid legal holidays during the effectivity of the CBA and that "[t]here is no condition, qualification or exception for any variance from the clear intent that all holidays shall be compensated."5 The Court of Appeals further held that "in the absence of an explicit provision in law which provides for [a] reduction of holiday pay if two holidays happen to fall on the same day, any doubt in the interpretation and implementation of the Labor Code provisions on holiday pay must be resolved in favor of labor." By the present petition, petitioners raise the following issues: I WHETHER OR NOT THE RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN ERRONEOUSLY INTERPRETING THE TERMS OF THE COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE PARTIES AND SUBSTITUTING ITS OWN JUDGMENT IN PLACE OF THE AGREEMENTS MADE BY THE PARTIES THEMSELVES II

WHETHER OR NOT THE SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT (DOLE) BY ISSUING EXPLANATORY BULLETIN DATED MARCH 11, 1993, IN THE GUISE OF PROVIDING GUIDELINES ON ART. 94 OF THE LABOR CODE, COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION, AS IT LEGISLATED AND INTERPRETED LEGAL PROVISIONS IN SUCH A MANNER AS TO CREATE OBLIGATIONS WHERE NONE ARE INTENDED BY THE LAW V WHETHER OR NOT THE RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN SUSTAINING THE SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR IN REITERATING ITS EXPLANATORY BULLETIN DATED MARCH 11, 1993 AND IN ORDERING THAT THE SAME POLICY OBTAINED FOR APRIL 9, 1998 DESPITE THE RULINGS OF THE SUPREME COURT TO THE CONTRARY VI WHETHER OR NOT RESPONDENTS ACTS WILL DEPRIVE PETITIONER OF PROPERTY WITHOUT DUE PROCESS BY THE "EXPLANATORY BULLETIN" AS WELL AS EQUAL PROTECTION OF LAWS The petition is devoid of merit.

WHETHER OR NOT THE RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN HOLDING THAT ANY DOUBTS ABOUT THE VALIDITY OF THE POLICIES ENUNCIATED IN THE EXPLANATORY BULLETIN WAS LAID TO REST BY THE REISSUANCE OF THE SAID EXPLANATORY BULLETIN III WHETHER OR NOT THE RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN UPHOLDING THE VALIDITY OF THE EXPLANATORY BULLETIN EVEN WHILE ADMITTING THAT THE SAID BULLEITN WAS NOT AN EXAMPLE OF A JUDICIAL, QUASI-JUDICIAL, OR ONE OF THE RULES AND REGULATIONS THAT [Department of Labor and Employment] DOLE MAY PROMULGATE IV

At the outset, it bears noting that instead of assailing the Court of Appeals Decision by petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, petitioner lodged the present petition for certiorari under Rule 65. [S]ince the Court of Appeals had jurisdiction over the petition under Rule 65, any alleged errors committed by it in the exercise of its jurisdiction would be errors of judgment which are reviewable by timely appeal and not by a special civil action of certiorari. If the aggrieved party fails to do so within the reglementary period, and the decision accordingly becomes final and executory, he cannot avail himself of the writ of certiorari, his predicament being the effect of his deliberate inaction. The appeal from a final disposition of the Court of Appeals is a petition for review under Rule 45 and not a special civil action under Rule 65

6

of the Rules of Court, now Rule 45 and Rule 65, respectively, of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure. Rule 45 is clear that the decisions, final orders or resolutions of the Court of Appeals in any case, i.e., regardless of the nature of the action or proceeding involved, may be appealed to this Court by filing a petition for review, which would be but a continuation of the appellate process over the original case. Under Rule 45 the reglementary period to appeal is fifteen (15) days from notice of judgment or denial of motion for reconsideration. xxx For the writ of certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court to issue, a petitioner must show that he has no plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of law against its perceived grievance. A remedy is considered "plain, speedy and adequate" if it will promptly relieve the petitioner from the injurious effects of the judgment and the acts of the lower court or agency. In this case, appeal was not only available but also a speedy and adequate remedy.6 The records of the case show that following petitioners receipt on August 18, 2000 of a copy of the August 10, 2000 Resolution of the Court of Appeals denying its Motion for Reconsideration, it filed the present petition for certiorari on September 15, 2000, at which time the Court of Appeals decision had become final and executory, the 15-day period to appeal it under Rule 45 having expired. Technicality aside, this Court finds no ground to disturb the assailed decision. Holiday pay is a legislated benefit enacted as part of the Constitutional imperative that the State shall afford protection to labor.7 Its purpose is not merely "to prevent diminution of the monthly income of the workers on account of work interruptions. In other words, although the worker is forced to take a rest, he earns what he should earn, that is, his holiday pay."8 It is also intended to enable the worker to participate in the national celebrations held during the days identified as with great historical and cultural significance.

Independence Day (June 12), Araw ng Kagitingan (April 9), National Heroes Day (last Sunday of August), Bonifacio Day (November 30) and Rizal Day (December 30) were declared national holidays to afford Filipinos with a recurring opportunity to commemorate the heroism of the Filipino people, promote national identity, and deepen the spirit of patriotism. Labor Day (May 1) is a day traditionally reserved to celebrate the contributions of the working class to the development of the nation, while the religious holidays designated in Executive Order No. 203 allow the worker to celebrate his faith with his family. As reflected above, Art. 94 of the Labor Code, as amended, affords a worker the enjoyment of ten paid regular holidays.9 The provision is mandatory,10 regardless of whether an employee is paid on a monthly or daily basis.11 Unlike a bonus, which is a management prerogative,12 holiday pay is a statutory benefit demandable under the law. Since a worker is entitled to the enjoyment of ten paid regular holidays, the fact that two holidays fall on the same date should not operate to reduce to nine the ten holiday pay benefits a worker is entitled to receive. It is elementary, under the rules of statutory construction, that when the language of the law is clear and unequivocal, the law must be taken to mean exactly what it says.13 In the case at bar, there is nothing in the law which provides or indicates that the entitlement to ten days of holiday pay shall be reduced to nine when two holidays fall on the same day. Petitioners assertion that Wellington v. Trajano14 has "overruled" the DOLE March 11, 1993 Explanatory Bulletin does not lie. In Wellington, the issue was whether monthly-paid employees are entitled to an additional days pay if a holiday falls on a Sunday. This Court, in answering the issue in the negative, observed that in fixing the monthly salary of its employees, Wellington took into account "every working day of the year including the holidays specified by law and excluding only Sunday." In the instant case, the issue is whether dailypaid employees are entitled to be paid for two regular holidays which fall on the same day.15 In any event, Art. 4 of the Labor Code provides that all doubts in the implementation and interpretation of its provisions, including its

7

implementing rules and regulations, shall be resolved in favor of labor. For the working mans welfare should be the primordial and paramount consideration.16 Moreover, Sec. 11, Rule IV, Book III of the Omnibus Rules to Implement the Labor Code provides that "Nothing in the law or the rules shall justify an employer in withdrawing or reducing any benefits, supplements or payments for unworked regular holidays as provided in existing individual or collective agreement or employer practice or policy."17 From the pertinent provisions of the CBA entered into by the parties, petitioner had obligated itself to pay for the legal holidays as required by law. Thus, the 1997-1998 CBA incorporates the following provision: ARTICLE XIV PAID LEGAL HOLIDAYS The following legal holidays shall be paid by the COMPANY as required by law: 1. New Years Day (January 1st) 2. Holy Thursday (moveable) 3. Good Friday (moveable) 4. Araw ng Kagitingan (April 9th) 5. Labor Day (May 1st) 6. Independence Day (June 12th) 7. Bonifacio Day [November 30] 8. Christmas Day (December 25th) 9. Rizal Day (December 30th) 10. General Election designated by law, if declared public nonworking holiday 11. National Heroes Day (Last Sunday of August) Only an employee who works on the day immediately preceding or after a regular holiday shall be entitled to the holiday pay. A paid legal holiday occurring during the scheduled vacation leave will result in holiday payment in addition to normal vacation pay but will not entitle the employee to another vacation leave.

Under similar circumstances, the COMPANY will give a days wage for November 1st and December 31st whenever declared a holiday. When required to work on said days, the employee will be paid according to Art. VI, Sec. 3B hereof.18 WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby DISMISSED. SO ORDERED.

-Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila FIRST DIVISION G.R. No. L-65482 December 1, 1987 JOSE RIZAL COLLEGE, petitioner, vs. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION AND NATIONAL ALLIANCE OF TEACHERS/OFFICE WORKERS, respondents. PARAS, J.: This is a petition for certiorari with prayer for the issuance of a writ of preliminary injunction, seeking the annulment of the decision of the National Labor Relations Commission * in NLRC Case No. RB-IV 2303778 (Case No. R4-1-1081-71) entitled "National Alliance of Teachers and Office Workers and Juan E. Estacio, Jaime Medina, et al. vs. Jose Rizal College" modifying the decision of the Labor Arbiter as follows: WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing considerations, the decision appealed from is MODIFIED, in the sense that teaching personnel paid by the hour are hereby declared to be entitled to holiday pay.

SO ORDERED. The factual background of this case which is undisputed is as follows: Petitioner is a non-stock, non-profit educational institution duly organized and existing under the laws of the Philippines. It has three groups of employees categorized as follows: (a) personnel on monthly basis, who receive their monthly salary uniformly throughout the year, irrespective of the actual number of working days in a month without deduction for holidays; (b) personnel on daily basis who are paid on actual days worked and they receive unworked holiday pay and (c) collegiate faculty who are paid on the basis of student contract hour. Before the start of the semester they sign contracts with the college undertaking to meet their classes as per schedule. Unable to receive their corresponding holiday pay, as claimed, from 1975 to 1977, private respondent National Alliance of Teachers and Office Workers (NATOW) in behalf of the faculty and personnel of Jose Rizal College filed with the Ministry of Labor a complaint against the college for said alleged non-payment of holiday pay, docketed as Case No. R04-10-81-72. Due to the failure of the parties to settle their differences on conciliation, the case was certified for compulsory arbitration where it was docketed as RB-IV-23037-78 (Rollo, pp. 155156). After the parties had submitted their respective position papers, the Labor Arbiter ** rendered a decision on February 5, 1979, the dispositive portion of which reads: WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered as follows: 1. The faculty and personnel of the respondent Jose Rizal College who are paid their salary by the month uniformly in a school year, irrespective of the number of working days in a month, without deduction for holidays, are presumed to be already paid the 10 paid legal holidays and are no longer entitled to separate payment for the said regular holidays; 2. The personnel of the respondent Jose Rizal College who are paid their wages daily are entitled to be paid the 10 unworked regular

holidays according to the pertinent provisions of the Rules and Regulations Implementing the Labor Code; 3. Collegiate faculty of the respondent Jose Rizal College who by contract are paid compensation per student contract hour are not entitled to unworked regular holiday pay considering that these regular holidays have been excluded in the programming of the student contact hours. (Rollo. pp. 26-27) On appeal, respondent National Labor Relations Commission in a decision promulgated on June 2, 1982, modified the decision appealed from, in the sense that teaching personnel paid by the hour are declared to be entitled to holiday pay (Rollo. p. 33). Hence, this petition. The sole issue in this case is whether or not the school faculty who according to their contracts are paid per lecture hour are entitled to unworked holiday pay. Labor Arbiter Julio Andres, Jr. found that faculty and personnel employed by petitioner who are paid their salaries monthly, are uniformly paid throughout the school year regardless of working days, hence their holiday pay are included therein while the daily paid employees are renumerated for work performed during holidays per affidavit of petitioner's treasurer (Rollo, pp. 72-73). There appears to be no problem therefore as to the first two classes or categories of petitioner's workers. The problem, however, lies with its faculty members, who are paid on an hourly basis, for while the Labor Arbiter sustains the view that said instructors and professors are not entitled to holiday pay, his decision was modified by the National Labor Relations Commission holding the contrary. Otherwise stated, on appeal the NLRC ruled that teaching personnel paid by the hour are declared to be entitled to holiday pay. Petitioner maintains the position among others, that it is not covered by Book V of the Labor Code on Labor Relations considering that it is

9

a non- profit institution and that its hourly paid faculty members are paid on a "contract" basis because they are required to hold classes for a particular number of hours. In the programming of these student contract hours, legal holidays are excluded and labelled in the schedule as "no class day. " On the other hand, if a regular week day is declared a holiday, the school calendar is extended to compensate for that day. Thus petitioner argues that the advent of any of the legal holidays within the semester will not affect the faculty's salary because this day is not included in their schedule while the calendar is extended to compensate for special holidays. Thus the programmed number of lecture hours is not diminished (Rollo, pp. 157158). The Solicitor General on the other hand, argues that under Article 94 of the Labor Code (P.D. No. 442 as amended), holiday pay applies to all employees except those in retail and service establishments. To deprive therefore employees paid at an hourly rate of unworked holiday pay is contrary to the policy considerations underlying such presidential enactment, and its precursor, the Blue Sunday Law (Republic Act No. 946) apart from the constitutional mandate to grant greater rights to labor (Constitution, Article II, Section 9). (Reno, pp. 7677). In addition, respondent National Labor Relations Commission in its decision promulgated on June 2, 1982, ruled that the purpose of a holiday pay is obvious; that is to prevent diminution of the monthly income of the workers on account of work interruptions. In other words, although the worker is forced to take a rest, he earns what he should earn. That is his holiday pay. It is no excuse therefore that the school calendar is extended whenever holidays occur, because such happens only in cases of special holidays (Rollo, p. 32). Subject holiday pay is provided for in the Labor Code (Presidential Decree No. 442, as amended), which reads: Art. 94. Right to holiday pay (a) Every worker shall be paid his regular daily wage during regular holidays, except in retail and service establishments regularly employing less than ten (10) workers;

(b) The employer may require an employee to work on any holiday but such employee shall be paid a compensation equivalent to twice his regular rate; ... " and in the Implementing Rules and Regulations, Rule IV, Book III, which reads: SEC. 8. Holiday pay of certain employees. (a) Private school teachers, including faculty members of colleges and universities, may not be paid for the regular holidays during semestral vacations. They shall, however, be paid for the regular holidays during Christmas vacations. ... Under the foregoing provisions, apparently, the petitioner, although a non-profit institution is under obligation to give pay even on unworked regular holidays to hourly paid faculty members subject to the terms and conditions provided for therein. We believe that the aforementioned implementing rule is not justified by the provisions of the law which after all is silent with respect to faculty members paid by the hour who because of their teaching contracts are obliged to work and consent to be paid only for work actually done (except when an emergency or a fortuitous event or a national need calls for the declaration of special holidays). Regular holidays specified as such by law are known to both school and faculty members as no class days;" certainly the latter do not expect payment for said unworked days, and this was clearly in their minds when they entered into the teaching contracts. On the other hand, both the law and the Implementing Rules governing holiday pay are silent as to payment on Special Public Holidays. It is readily apparent that the declared purpose of the holiday pay which is the prevention of diminution of the monthly income of the employees on account of work interruptions is defeated when a regular class day is cancelled on account of a special public holiday and class hours are held on another working day to make up for time lost in the school calendar. Otherwise stated, the faculty member, although forced to take a rest, does not earn what he should earn on

10

that day. Be it noted that when a special public holiday is declared, the faculty member paid by the hour is deprived of expected income, and it does not matter that the school calendar is extended in view of the days or hours lost, for their income that could be earned from other sources is lost during the extended days. Similarly, when classes are called off or shortened on account of typhoons, floods, rallies, and the like, these faculty members must likewise be paid, whether or not extensions are ordered. Petitioner alleges that it was deprived of due process as it was not notified of the appeal made to the NLRC against the decision of the labor arbiter. The Court has already set forth what is now known as the "cardinal primary" requirements of due process in administrative proceedings, to wit: "(1) the right to a hearing which includes the right to present one's case and submit evidence in support thereof; (2) the tribunal must consider the evidence presented; (3) the decision must have something to support itself; (4) the evidence must be substantial, and substantial evidence means such evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion; (5) the decision must be based on the evidence presented at the hearing, or at least contained in the record and disclosed to the parties affected; (6) the tribunal or body of any of its judges must act on its or his own independent consideration of the law and facts of the controversy, and not simply accept the views of a subordinate; (7) the board or body should in all controversial questions, render its decisions in such manner that the parties to the proceeding can know the various issues involved, and the reason for the decision rendered. " (Doruelo vs. Commission on Elections, 133 SCRA 382 [1984]). The records show petitioner JRC was amply heard and represented in the instant proceedings. It submitted its position paper before the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC and even filed a motion for reconsideration of the decision of the latter, as well as an "Urgent Motion for Hearing En Banc" (Rollo, p. 175). Thus, petitioner's claim of lack of due process is unfounded. PREMISES CONSIDERED, the decision of respondent National Labor Relations Commission is hereby set aside, and a new one is hereby RENDERED:

(a) exempting petitioner from paying hourly paid faculty members their pay for regular holidays, whether the same be during the regular semesters of the school year or during semestral, Christmas, or Holy Week vacations; (b) but ordering petitioner to pay said faculty members their regular hourly rate on days declared as special holidays or for some reason classes are called off or shortened for the hours they are supposed to have taught, whether extensions of class days be ordered or not; in case of extensions said faculty members shall likewise be paid their hourly rates should they teach during said extensions. SO ORDERED.

-Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila SECOND DIVISION G.R. No. 114698 July 3, 1995 WELLINGTON INVESTMENT AND MANUFACTURING CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. CRESENCIANO B. TRAJANO, Under-Secretary of Labor and Employment, ELMER ABADILLA, and 34 others, respondents.

NARVASA, C.J.: The basic issue raised by petitioner in this case is, as its counsel puts it, "whether or not a monthly-paid employee, receiving a fixed monthly

11

compensation, is entitled to an additional pay aside from his usual holiday pay, whenever a regular holiday falls on a Sunday." The case arose from a routine inspection conducted by a Labor Enforcement Officer on August 6, 1991 of the Wellington Flour Mills, an establishment owned and operated by petitioner Wellington Investment and Manufacturing Corporation (hereafter, simply Wellington). The officer thereafter drew up a report, a copy of which was "explained to and received by" Wellington's personnel manager, in which he set forth his finding of "(n)on-payment of regular holidays falling on a Sunday for monthly-paid employees." 1 Wellington sought reconsideration of the Labor Inspector's report, by letter dated August 10, 1991. It argued that "the monthly salary of the company's monthly-salaried employees already includes holiday pay for all regular holidays . . . (and hence) there is no legal basis for the finding of alleged non-payment of regular holidays falling on a Sunday." 2 It expounded on this thesis in a position paper subsequently submitted to the Regional Director, asserting that it pays its monthlypaid employees a fixed monthly compensation "using the 314 factor which undeniably covers and already includes payment for all the working days in a month as well as all the 10 unworked regular holidays within a year." 3 Wellington's arguments failed to persuade the Regional Director who, in an Order issued on July 28, 1992, ruled that "when a regular holiday falls on a Sunday, an extra or additional working day is created and the employer has the obligation to pay the employees for the extra day except the last Sunday of August since the payment for the said holiday is already included in the 314 factor," and accordingly directed Wellington to pay its employees compensation corresponding to four (4) extra working days. 4 Wellington timely filed a motion for reconsideration of this Order of August 10, 1992, pointing out that it was in effect being compelled to "shell out an additional pay for an alleged extra working day" despite its complete payment of all compensation lawfully due its workers, using the 314 factor. 5 Its motion was treated as an appeal and was acted on by respondent Undersecretary. By Order dated September 22, the latter affirmed the challenged order of the Regional Director, holding that "the divisor being used by the respondent (Wellington)

does not reliably reflect the actual working days in a year, " and consequently commanded Wellington to pay its employees the "six additional working days resulting from regular holidays falling on Sundays in 1988, 1989 and 1990." 6 Again, Wellington moved for reconsideration, 7 and again was rebuffed. 8 Wellington then instituted the special civil action of certiorari at bar in an attempt to nullify the orders above mentioned. By Resolution dated July 4, 1994, this Court authorized the issuance of a temporary restraining order enjoining the respondents from enforcing the questioned orders. 9 Every worker should, according to the Labor Code, 10 "be paid his regular daily wage during regular holidays, except in retail and service establishments regularly employing less than ten (10) workers;" this, of course, even if the worker does no work on these holidays. The regular holidays include: "New Year's Day, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, the ninth of April, the first of May, the twelfth of June, the fourth of July, the thirtieth of November, the twenty-fifth of December, and the day designated by law for holding a general election (or national referendum or plebiscite). 11 Particularly as regards employees "who are uniformly paid by the month, "the monthly minimum wage shall not be less than the statutory minimum wage multiplied by 365 days divided by twelve." 12 This monthly salary shall serve as compensation "for all days in the month whether worked or not," and "irrespective of the number of working days therein." 13 In other words, whether the month is of thirty (30) or thirty-one (31) days' duration, or twenty-eight (28) or twentynine (29) (as in February), the employee is entitled to receive the entire monthly salary. So, too, in the event of the declaration of any special holiday, or any fortuitous cause precluding work on any particular day or days (such as transportation strikes, riots, or typhoons or other natural calamities), the employee is entitled to the salary for the entire month and the employer has no right to deduct the proportionate amount corresponding to the days when no work was done. The monthly compensation is evidently intended precisely to avoid computations and adjustments resulting from the contingencies just mentioned which are routinely made in the case of workers paid on daily basis.

12

In Wellington's case, there seems to be no question that at the time of the inspection conducted by the Labor Enforcement Officer on August 6, 1991, it was and had been paying its employees "a salary of not less than the statutory or established minimum wage," and that the monthly salary thus paid was "not . . . less than the statutory minimum wage multiplied by 365 days divided by twelve," supra. There is, in other words, no issue that to this extent, Wellington complied with the minimum norm laid down by law. Apparently the monthly salary was fixed by Wellington to provide for compensation for every working day of the year including the holidays specified by law and excluding only Sundays. In fixing the salary, Wellington used what it calls the "314 factor;" that is to say, it simply deducted 51 Sundays from the 365 days normally comprising a year and used the difference, 314, as basis for determining the monthly salary. The monthly salary thus fixed actually covers payment for 314 days of the year, including regular and special holidays, as well as days when no work is done by reason of fortuitous cause, as above specified, or causes not attributable to the employees. The Labor Officer who conducted the routine inspection of Wellington discovered that in certain years, two or three regular holidays had fallen on Sundays. He reasoned that this had precluded the enjoyment by the employees of a non-working day, and the employees had consequently had to work an additional day for that month. This ratiocination received the approval of his Regional Director who opined 14 that "when a regular holiday falls on a Sunday, an extra or additional working day is created and the employer has the obligation to pay its employees for the extra day except the last Sunday of August since the payment for the said holiday is already included in the 314 factor." 15 This ingenuous theory was adopted and further explained by respondent Labor Undersecretary, to whom the matter was appealed, as follows: 16 . . . By using said (314) factor, the respondent (Wellington) assumes that all the regular holidays fell on ordinary days and never on a Sunday. Thus, the respondent failed to consider the circumstance that whenever a regular holiday coincides with a Sunday, an additional working day is created and left unpaid. In other words, while the said

divisor may be utilized as proof evidencing payment of 302 working days, 2 special days and the ten regular holidays in a calendar year, the same does not cover or include payment of additional working days created as a result of some regular holidays falling on Sundays. He pointed out that in 1988 there was "an increase of three (3) working days resulting from regular holidays falling on Sundays;" hence Wellington "should pay for 317 days, instead of 314 days." By the same process of ratiocination, respondent Undersecretary theorized that there should be additional payment by Wellington to its monthly-paid employees for "an increment of three (3) working days" for 1989 and again, for 1990. What he is saying is that in those years, Wellington should have used the "317 factor," not the "314 factor." The theory loses sight of the fact that the monthly salary in Wellington which is based on the so-called "314 factor" accounts for all 365 days of a year; i.e., Wellington's "314 factor" leaves no day unaccounted for; it is paying for all the days of a year with the exception only of 51 Sundays. The respondents' theory would make each of the years in question (1988, 1989, 1990), a year of 368 days. Pursuant to this theory, no employer opting to pay his employees by the month would have any definite basis to determine the number of days in a year for which compensation should be given to his work force. He would have to ascertain the number of times legal holidays would fall on Sundays in all the years of the expected or extrapolated lifetime of his business. Alternatively, he would be compelled to make adjustments in his employees' monthly salaries every year, depending on the number of times that a legal holiday fell on a Sunday. There is no provision of law requiring any employer to make such adjustments in the monthly salary rate set by him to take account of legal holidays falling on Sundays in a given year, or, contrary to the legal provisions bearing on the point, otherwise to reckon a year at more than 365 days. As earlier mentioned, what the law requires of employers opting to pay by the month is to assure that "the monthly minimum wage shall not be less than the statutory minimum wage multiplied by 365 days divided by twelve," 17 and to pay that salary "for all days in the month whether worked or not," and "irrespective of the number of working days therein." 18 That salary is due and payable

13

regardless of the declaration of any special holiday in the entire country or a particular place therein, or any fortuitous cause precluding work on any particular day or days (such as transportation strikes, riots, or typhoons or other natural calamities), or cause not imputable to the worker. And as also earlier pointed out, the legal provisions governing monthly compensation are evidently intended precisely to avoid re-computations and alterations in salary on account of the contingencies just mentioned, which, by the way, are routinely made between employer and employees when the wages are paid on daily basis. The public respondents argue that their challenged conclusions and dispositions may be justified by Section 2, Rule X, Book III of the Implementing Rules, giving the Regional Director power 19 . . . to order and administer (in cases where employeremployee relations still exist), after due notice and hearing, compliance with the labor standards provisions of the Code and the other labor legislations based on the findings of their Regulations Officers or Industrial Safety Engineers (Labor Standard and Welfare Officers) and made in the course of inspection, and to issue writs of execution to the appropriate authority for the enforcement of his order, in line with the provisions of Article 128 in relation to Articles 289 and 290 of the Labor Code, as amended. . . . The respondents beg the question. Their argument assumes that there are some "labor standards provisions of the Code and the other labor legislations" imposing on employers the obligation to give additional compensation to their monthly-paid employees in the event that a legal holiday should fall on a Sunday in a particular month with which compliance may be commanded by the Regional Director when the existence of said provisions is precisely the matter to be established. In promulgating the orders complained of the public respondents have attempted to legislate, or interpret legal provisions in such a manner as to create obligations where none are intended. They have acted without authority, or at the very least, with grave abuse of their discretion. Their acts must be nullified and set aside.

WHEREFORE, the orders complained of, namely: that of the respondent Undersecretary dated September 22, 1993, and that of the Regional Director dated July 30, 1992, are NULLIFIED AND SET ASIDE, and the proceeding against petitioner DISMISSED. SO ORDERED.

-Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila SECOND DIVISION G.R. No. 157634 May 16, 2005

MAYON HOTEL & RESTAURANT, PACITA O. PO and/or JOSEFA PO LAM, petitioners, vs. ROLANDO ADANA, CHONA BUMALAY, ROGER BURCE, EDUARDO ALAMARES, AMADO ALAMARES, EDGARDO TORREFRANCA, LOURDES CAMIGLA, TEODORO LAURENARIA, WENEFREDO LOVERES, LUIS GUADES, AMADO MACANDOG, PATERNO LLARENA, GREGORIO NICERIO, JOSE ATRACTIVO, MIGUEL TORREFRANCA, and SANTOS BROOLA, respondents. DECISION PUNO, J.: This is a petition for certiorari to reverse and set aside the Decision issued by the Court of Appeals (CA)1 in CA-G.R. SP No. 68642, entitled "Rolando Adana, Wenefredo Loveres, et. al. vs. National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC), Mayon Hotel & Restaurant/Pacita O. Po, et al.," and the Resolution2 denying petitioners' motion for reconsideration. The assailed CA decision reversed the NLRC Decision

14

which had dismissed all of respondents' complaints,3 and reinstated the Joint Decision of the Labor Arbiter4 which ruled that respondents were illegally dismissed and entitled to their money claims. The facts, culled from the records, are as follows:5 Petitioner Mayon Hotel & Restaurant is a single proprietor business registered in the name of petitioner Pacita O. Po,6 whose mother, petitioner Josefa Po Lam, manages the establishment.7 The hotel and restaurant employed about sixteen (16) employees. Records show that on various dates starting in 1981, petitioner hotel and restaurant hired the following people, all respondents in this case, with the following jobs: 1. Wenefredo Loveres 2. Paterno Llarena 3. Gregorio Nicerio 4. Amado Macandog 5. Luis Guades 6. Santos Broola 7. Teodoro Laurenaria 8. Eduardo Alamares 9. Lourdes Camigla 10. Chona Bumalay 11. Jose Atractivo 12. Amado Alamares 13. Roger Burce 14. Rolando Adana 15. Miguel Torrefranca 16. Edgardo Torrefranca Accountant and Officer-incharge Front Desk Clerk Supervisory Waiter Roomboy Utility/Maintenance Worker Roomboy Waiter Roomboy/Waiter Cashier Cashier Technician Dishwasher and Kitchen Helper Cook Waiter Cook Cook

Legazpi City.10 Only nine (9) of the sixteen (16) employees continued working in the Mayon Restaurant at its new site.11 On various dates of April and May 1997, the 16 employees filed complaints for underpayment of wages and other money claims against petitioners, as follows:12 Wenefredo Loveres, Luis Guades, Amado Macandog and Jose Atractivo for illegal dismissal, underpayment of wages, nonpayment of holiday and rest day pay; service incentive leave pay (SILP) and claims for separation pay plus damages; Paterno Llarena and Gregorio Nicerio for illegal dismissal with claims for underpayment of wages; nonpayment of cost of living allowance (COLA) and overtime pay; premium pay for holiday and rest day; SILP; nightshift differential pay and separation pay plus damages; Miguel Torrefranca, Chona Bumalay and Lourdes Camigla for underpayment of wages; nonpayment of holiday and rest day pay and SILP; Rolando Adana, Roger Burce and Amado Alamares for underpayment of wages; nonpayment of COLA, overtime, holiday, rest day, SILP and nightshift differential pay; Eduardo Alamares for underpayment of wages, nonpayment of holiday, rest day and SILP and night shift differential pay; Santos Broola for illegal dismissal, underpayment of wages, overtime pay, rest day pay, holiday pay, SILP, and damages;13 and Teodoro Laurenaria for underpayment of wages; nonpayment of COLA and overtime pay; premium pay for holiday and rest day, and SILP. On July 14, 2000, Executive Labor Arbiter Gelacio L. Rivera, Jr. rendered a Joint Decision in favor of the employees. The Labor Arbiter awarded substantially all of respondents' money claims, and held that respondents Loveres, Macandog and Llarena were entitled to

Due to the expiration and non-renewal of the lease contract for the rented space occupied by the said hotel and restaurant at Rizal Street, the hotel operations of the business were suspended on March 31, 1997.9 The operation of the restaurant was continued in its new location at Elizondo Street, Legazpi City, while waiting for the construction of a new Mayon Hotel & Restaurant at Pearanda Street,

15

separation pay, while respondents Guades, Nicerio and Alamares were entitled to their retirement pay. The Labor Arbiter also held that based on the evidence presented, Josefa Po Lam is the owner/proprietor of Mayon Hotel & Restaurant and the proper respondent in these cases. On appeal to the NLRC, the decision of the Labor Arbiter was reversed, and all the complaints were dismissed. Respondents filed a motion for reconsideration with the NLRC and when this was denied, they filed a petition for certiorari with the CA which rendered the now assailed decision. After their motion for reconsideration was denied, petitioners now come to this Court, seeking the reversal of the CA decision on the following grounds: I. The Honorable Court of Appeals erred in reversing the decision of the National Labor Relations Commission (Second Division) by holding that the findings of fact of the NLRC were not supported by substantial evidence despite ample and sufficient evidence showing that the NLRC decision is indeed supported by substantial evidence; II. The Honorable Court of Appeals erred in upholding the joint decision of the labor arbiter which ruled that private respondents were illegally dismissed from their employment, despite the fact that the reason why private respondents were out of work was not due to the fault of petitioners but to causes beyond the control of petitioners. III. The Honorable Court of Appeals erred in upholding the award of monetary benefits by the labor arbiter in his joint decision in favor of the private respondentS, including the award of damages to six (6) of the private respondents, despite the fact that the private respondents have not proven by substantial evidence their entitlement thereto and especially the fact that they were not illegally dismissed by the petitioners. IV. The Honorable Court of Appeals erred in holding that Pacita Ong Po is the owner of the business establishment, petitioner Mayon Hotel and Restaurant, thus disregarding the certificate of registration of the

business establishment ISSUED by the local government, which is a public document, and the unqualified admissions of complainantsprivate respondents.14 In essence, the petition calls for a review of the following issues: 1. Was it correct for petitioner Josefa Po Lam to be held liable as the owner of petitioner Mayon Hotel & Restaurant, and the proper respondent in this case? 2. Were respondents Loveres, Guades, Macandog, Atractivo, Llarena and Nicerio illegally dismissed? 3. Are respondents entitled to their money claims due to underpayment of wages, and nonpayment of holiday pay, rest day premium, SILP, COLA, overtime pay, and night shift differential pay? It is petitioners' contention that the above issues have already been threshed out sufficiently and definitively by the NLRC. They therefore assail the CA's reversal of the NLRC decision, claiming that based on the ruling in Castillo v. NLRC,15 it is non sequitur that the CA should reexamine the factual findings of both the NLRC and the Labor Arbiter, especially as in this case the NLRC's findings are allegedly supported by substantial evidence. We do not agree. There is no denying that it is within the NLRC's competence, as an appellate agency reviewing decisions of Labor Arbiters, to disagree with and set aside the latter's findings.16 But it stands to reason that the NLRC should state an acceptable cause therefore, otherwise it would be a whimsical, capricious, oppressive, illogical, unreasonable exercise of quasi-judicial prerogative, subject to invalidation by the extraordinary writ of certiorari.17 And when the factual findings of the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC are diametrically opposed and this disparity of findings is called into question, there is, necessarily, a reexamination of the factual findings to ascertain which opinion should be sustained.18 As ruled in Asuncion v. NLRC,19

16

Although, it is a legal tenet that factual findings of administrative bodies are entitled to great weight and respect, we are constrained to take a second look at the facts before us because of the diversity in the opinions of the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC. A disharmony between the factual findings of the Labor Arbiter and those of the NLRC opens the door to a review thereof by this Court.20 The CA, therefore, did not err in reviewing the records to determine which opinion was supported by substantial evidence. Moreover, it is explicit in Castillo v. NLRC21 that factual findings of administrative bodies like the NLRC are affirmed only if they are supported by substantial evidence that is manifest in the decision and on the records. As stated in Castillo: [A]buse of discretion does not necessarily follow from a reversal by the NLRC of a decision of a Labor Arbiter. Mere variance in evidentiary assessment between the NLRC and the Labor Arbiter does not automatically call for a full review of the facts by this Court. The NLRC's decision, so long as it is not bereft of substantial support from the records, deserves respect from this Court. As a rule, the original and exclusive jurisdiction to review a decision or resolution of respondent NLRC in a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court does not include a correction of its evaluation of the evidence but is confined to issues of jurisdiction or grave abuse of discretion. Thus, the NLRC's factual findings, if supported by substantial evidence, are entitled to great respect and even finality, unless petitioner is able to show that it simply and arbitrarily disregarded the evidence before it or had misappreciated the evidence to such an extent as to compel a contrary conclusion if such evidence had been properly appreciated. (citations omitted)22 After careful review, we find that the reversal of the NLRC's decision was in order precisely because it was not supported by substantial evidence. 1. Ownership by Josefa Po Lam The Labor Arbiter ruled that as regards the claims of the employees, petitioner Josefa Po Lam is, in fact, the owner of Mayon Hotel &

Restaurant. Although the NLRC reversed this decision, the CA, on review, agreed with the Labor Arbiter that notwithstanding the certificate of registration in the name of Pacita Po, it is Josefa Po Lam who is the owner/proprietor of Mayon Hotel & Restaurant, and the proper respondent in the complaints filed by the employees. The CA decision states in part: [Despite] the existence of the Certificate of Registration in the name of Pacita Po, we cannot fault the labor arbiter in ruling that Josefa Po Lam is the owner of the subject hotel and restaurant. There were conflicting documents submitted by Josefa herself. She was ordered to submit additional documents to clearly establish ownership of the hotel and restaurant, considering the testimonies given by the [respondents] and the non-appearance and failure to submit her own position paper by Pacita Po. But Josefa did not comply with the directive of the Labor Arbiter. The ruling of the Supreme Court in Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company v. Court of Appeals applies to Josefa Po Lam which is stated in this wise: When the evidence tends to prove a material fact which imposes a liability on a party, and he has it in his power to produce evidence which from its very nature must overthrow the case made against him if it is not founded on fact, and he refuses to produce such evidence, the presumption arises that the evidence[,] if produced, would operate to his prejudice, and support the case of his adversary. Furthermore, in ruling that Josefa Po Lam is the real owner of the hotel and restaurant, the labor arbiter relied also on the testimonies of the witnesses, during the hearing of the instant case. When the conclusions of the labor arbiter are sufficiently corroborated by evidence on record, the same should be respected by appellate tribunals, since he is in a better position to assess and evaluate the credibility of the contending parties.23 (citations omitted) Petitioners insist that it was error for the Labor Arbiter and the CA to have ruled that petitioner Josefa Po Lam is the owner of Mayon Hotel & Restaurant. They allege that the documents they submitted to the Labor Arbiter sufficiently and clearly establish the fact of ownership by petitioner Pacita Po, and not her mother, petitioner Josefa Po Lam. They contend that petitioner Josefa Po Lam's participation was limited to merely (a) being the overseer; (b) receiving the month-to-month

17

and/or year-to-year financial reports prepared and submitted by respondent Loveres; and (c) visitation of the premises.24 They also put emphasis on the admission of the respondents in their position paper submitted to the Labor Arbiter, identifying petitioner Josefa Po Lam as the manager, and Pacita Po as the owner.25 This, they claim, is a judicial admission and is binding on respondents. They protest the reliance the Labor Arbiter and the CA placed on their failure to submit additional documents to clearly establish ownership of the hotel and restaurant, claiming that there was no need for petitioner Josefa Po Lam to submit additional documents considering that the Certificate of Registration is the best and primary evidence of ownership. We disagree with petitioners. We have scrutinized the records and find the claim that petitioner Josefa Po Lam is merely the overseer is not borne out by the evidence. First. It is significant that only Josefa Po Lam appeared in the proceedings with the Labor Arbiter. Despite receipt of the Labor Arbiter's notice and summons, other notices and Orders, petitioner Pacita Po failed to appear in any of the proceedings with the Labor Arbiter in these cases, nor file her position paper.26 It was only on appeal with the NLRC that Pacita Po signed the pleadings.27 The apathy shown by petitioner Pacita Po is contrary to human experience as one would think that the owner of an establishment would naturally be concerned when all her employees file complaints against her. Second. The records of the case belie petitioner Josefa Po Lam's claim that she is merely an overseer. The findings of the Labor Arbiter on this question were based on credible, competent and substantial evidence. We again quote the Joint Decision on this matter: Mayon Hotel and Restaurant is a [business name] of an enterprise. While [petitioner] Josefa Po Lam claims that it is her daughter, Pacita Po, who owns the hotel and restaurant when the latter purchased the same from one Palanos in 1981, Josefa failed to submit the document of sale from said Palanos to Pacita as allegedly the sale was only verbal although the license to operate said hotel and restaurant is in the name of Pacita which, despite our Order to Josefa to present the same, she failed to comply (p. 38, tsn. August 13, 1998). While several documentary evidences were submitted by Josefa wherein Pacita

was named therein as owner of the hotel and restaurant (pp. 64, 65, 67 to 69; vol. I, rollo)[,] there were documentary evidences also that were submitted by Josefa showing her ownership of said enterprise (pp. 468 to 469; vol. II, rollo). While Josefa explained her participation and interest in the business as merely to help and assist her daughter as the hotel and restaurant was near the former's store, the testimonies of [respondents] and Josefa as well as her demeanor during the trial in these cases proves (sic) that Josefa Po Lam owns Mayon Hotel and Restaurant. [Respondents] testified that it was Josefa who exercises all the acts and manifestation of ownership of the hotel and restaurant like transferring employees from the Greatwall Palace Restaurant which she and her husband Roy Po Lam previously owned; it is Josefa to whom the employees submits (sic) reports, draws money for payment of payables and for marketing, attending (sic) to Labor Inspectors during ocular inspections. Except for documents whereby Pacita Po appears as the owner of Mayon Hotel and Restaurant, nothing in the record shows any circumstance or manifestation that Pacita Po is the owner of Mayon Hotel and Restaurant. The least that can be said is that it is absurd for a person to purchase a hotel and restaurant in the very heart of the City of Legazpi verbally. Assuming this to be true, when [petitioners], particularly Josefa, was directed to submit evidence as to the ownership of Pacita of the hotel and restaurant, considering the testimonies of [respondents], the former should [have] submitted the lease contract between the owner of the building where Mayon Hotel and Restaurant was located at Rizal St., Legazpi City and Pacita Po to clearly establish ownership by the latter of said enterprise. Josefa failed. We are not surprised why some employers employ schemes to mislead Us in order to evade liabilities. We therefore consider and hold Josefa Po Lam as the owner/proprietor of Mayon Hotel and Restaurant and the proper respondent in these cases.28 Petitioners' reliance on the rules of evidence, i.e., the certificate of registration being the best proof of ownership, is misplaced. Notwithstanding the certificate of registration, doubts were cast as to the true nature of petitioner Josefa Po Lam's involvement in the enterprise, and the Labor Arbiter had the authority to resolve this issue. It was therefore within his jurisdiction to require the additional documents to ascertain who was the real owner of petitioner Mayon Hotel & Restaurant.

18

Article 221 of the Labor Code is clear: technical rules are not binding, and the application of technical rules of procedure may be relaxed in labor cases to serve the demand of substantial justice.29 The rule of evidence prevailing in court of law or equity shall not be controlling in labor cases and it is the spirit and intention of the Labor Code that the Labor Arbiter shall use every and all reasonable means to ascertain the facts in each case speedily and objectively and without regard to technicalities of law or procedure, all in the interest of due process.30 Labor laws mandate the speedy administration of justice, with least attention to technicalities but without sacrificing the fundamental requisites of due process.31 Similarly, the fact that the respondents' complaints contained no allegation that petitioner Josefa Po Lam is the owner is of no moment. To apply the concept of judicial admissions to respondents who are but lowly employees - would be to exact compliance with technicalities of law that is contrary to the demands of substantial justice. Moreover, the issue of ownership was an issue that arose only during the course of the proceedings with the Labor Arbiter, as an incident of determining respondents' claims, and was well within his jurisdiction.32 Petitioners were also not denied due process, as they were given sufficient opportunity to be heard on the issue of ownership.33 The essence of due process in administrative proceedings is simply an opportunity to explain one's side or an opportunity to seek reconsideration of the action or ruling complained of.34 And there is nothing in the records which would suggest that petitioners had absolute lack of opportunity to be heard.35 Obviously, the choice not to present evidence was made by petitioners themselves.36 But more significantly, we sustain the Labor Arbiter and the CA because even when the case was on appeal with the NLRC, nothing was submitted to negate the Labor Arbiter's finding that Pacita Po is not the real owner of the subject hotel and restaurant. Indeed, no such evidence was submitted in the proceedings with the CA nor with this Court. Considering that petitioners vehemently deny ownership by petitioner Josefa Po Lam, it is most telling that they continue to withhold evidence which would shed more light on this issue. We therefore agree with the CA that the failure to submit could only

mean that if produced, it would have been adverse to petitioners' case.37 Thus, we find that there is substantial evidence to rule that petitioner Josefa Po Lam is the owner of petitioner Mayon Hotel & Restaurant. 2. Illegal Dismissal: claim for separation pay Of the sixteen employees, only the following filed a case for illegal dismissal: respondents Loveres, Llarena, Nicerio, Macandog, Guades, Atractivo and Broola.38 The Labor Arbiter found that there was illegal dismissal, and granted separation pay to respondents Loveres, Macandog and Llarena. As respondents Guades, Nicerio and Alamares were already 79, 66 and 65 years old respectively at the time of the dismissal, the Labor Arbiter granted retirement benefits pursuant to Article 287 of the Labor Code as amended.39 The Labor Arbiter ruled that respondent Atractivo was not entitled to separation pay because he had been transferred to work in the restaurant operations in Elizondo Street, but awarded him damages. Respondents Loveres, Llarena, Nicerio, Macandog and Guades were also awarded damages.40 The NLRC reversed the Labor Arbiter, finding that "no clear act of termination is attendant in the case at bar" and that respondents "did not submit any evidence to that effect, but the finding and conclusion of the Labor Arbiter [are] merely based on his own surmises and conjectures."41 In turn, the NLRC was reversed by the CA. It is petitioners contention that the CA should have sustained the NLRC finding that none of the above-named respondents were illegally dismissed, or entitled to separation or retirement pay. According to petitioners, even the Labor Arbiter and the CA admit that when the illegal dismissal case was filed by respondents on April 1997, they had as yet no cause of action. Petitioners therefore conclude that the filing by respondents of the illegal dismissal case was premature and should have been dismissed outright by the Labor Arbiter.42 Petitioners also claim that since the validity of respondents' dismissal is a factual question, it is not for the reviewing court to weigh the conflicting evidence.43

19

We do not agree. Whether respondents are still working for petitioners is a factual question. And the records are unequivocal that since April 1997, when petitioner Mayon Hotel & Restaurant suspended its hotel operations and transferred its restaurant operations in Elizondo Street, respondents Loveres, Macandog, Llarena, Guades and Nicerio have not been permitted to work for petitioners. Respondent Alamares, on the other hand, was also laid-off when the Elizondo Street operations closed, as were all the other respondents. Since then, respondents have not been permitted to work nor recalled, even after the construction of the new premises at Pearanda Street and the reopening of the hotel operations with the restaurant in this new site. As stated by the Joint Decision of the Labor Arbiter on July 2000, or more than three (3) years after the complaint was filed:44 [F]rom the records, more than six months had lapsed without [petitioner] having resumed operation of the hotel. After more than one year from the temporary closure of Mayon Hotel and the temporary transfer to another site of Mayon Restaurant, the building which [petitioner] Josefa allege[d] w[h]ere the hotel and restaurant will be transferred has been finally constructed and the same is operated as a hotel with bar and restaurant nevertheless, none of [respondents] herein who were employed at Mayon Hotel and Restaurant which was also closed on April 30, 1998 was/were recalled by [petitioner] to continue their services... Parenthetically, the Labor Arbiter did not grant separation pay to the other respondents as they had not filed an amended complaint to question the cessation of their employment after the closure of Mayon Hotel & Restaurant on March 31, 1997.45 The above factual finding of the Labor Arbiter was never refuted by petitioners in their appeal with the NLRC. It confounds us, therefore, how the NLRC could have so cavalierly treated this uncontroverted factual finding by ruling that respondents have not introduced any evidence to show that they were illegally dismissed, and that the Labor Arbiter's finding was based on conjecture.46 It was a serious error that the NLRC did not inquire as to the legality of the cessation of employment. Article 286 of the Labor Code is clear there is termination of employment when an otherwise bona fide suspension of work exceeds six (6) months.47 The cessation of employment for

more than six months was patent and the employer has the burden of proving that the termination was for a just or authorized cause.48 Moreover, we are not impressed by any of petitioners' attempts to exculpate themselves from the charges. First, in the proceedings with the Labor Arbiter, they claimed that it could not be illegal dismissal because the lay-off was merely temporary (and due to the expiration of the lease contract over the old premises of the hotel). They specifically invoked Article 286 of the Labor Code to argue that the claim for separation pay was premature and without legal and factual basis.49 Then, because the Labor Arbiter had ruled that there was already illegal dismissal when the lay-off had exceeded the sixmonth period provided for in Article 286, petitioners raise this novel argument, to wit: It is the firm but respectful submission of petitioners that reliance on Article 286 of the Labor Code is misplaced, considering that the reason why private respondents were out of work was not due to the fault of petitioners. The failure of petitioners to reinstate the private respondents to their former positions should not likewise be attributable to said petitioners as the private respondents did not submit any evidence to prove their alleged illegal dismissal. The petitioners cannot discern why they should be made liable to the private respondents for their failure to be reinstated considering that the fact that they were out of work was not due to the fault of petitioners but due to circumstances beyond the control of petitioners, which are the termination and non-renewal of the lease contract over the subject premises. Private respondents, however, argue in their Comment that petitioners themselves sought the application of Article 286 of the Labor Code in their case in their Position Paper filed before the Labor Arbiter. In refutation, petitioners humbly submit that even if they invoke Article 286 of the Labor Code, still the fact remains, and this bears stress and emphasis, that the temporary suspension of the operations of the establishment arising from the non-renewal of the lease contract did not result in the termination of employment of private respondents and, therefore, the petitioners cannot be faulted if said private respondents were out of work, and consequently, they are not entitled to their money claims against the petitioners.50

20