Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Aztreonam Review

Hochgeladen von

ncpscientist_2Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Aztreonam Review

Hochgeladen von

ncpscientist_2Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

AZTREONAM

BURKE A. CUNHA, M.D.

From the Infectious Disease Division, Winthrop-University Hospital, Mineola, and the School of Medicine, State University of New York, Stony Brook, New York ABSTRACT-Axtreonam is the first monobactam and is unique among fl-hutam antibiotics for its spectrum of activity that is exclusively active agai:$::t gram-negative aerobic bacteria. Broad clinical experience with this agent suplports its use in the treatment of adults with severe or complicated urologic infections. Axtreonam may be safely used in patients with penicillin allergy. With a spectrum of activity that is comparable to the aminoglycosides bz t without the potential for ototoxicity or nephrotoxicity, axtreonam represent,s a rational choice of therapy for treatment of systemic urinary tract infections due to susceptible organisms. Urinary tract infections are a significant source of morbidity and mortality in the hospitalized patient. Approximately 500,000 urinary tract infections occur annually in acute-care hospitals in the United States, and nosocomial urosepsis is responsible for over 3,500 deaths each year.2 The urinary tract is the site of origin for approximately 40 percent of gram-negative bacillary bacteremias that develop in patients.3 Traditional therapy of serious urinary tract infections with or without urologic complications consists of parenteral antibiotics. Aminoglycosides are frequently used in this setting because they achieve high concentrations in blood, renal tissue, and urine. In addition, the aminoglycosides are bactericidal and are active against many aerobic gram-negative uropathogens, including the Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The potential for toxicity remains a significant disadvantage to aminoglycoside therapy, and therapeutic serum concentration monitoring elevates the cost of therapy and complicates patient management. Economic analysis of aminoglycoside therapy has shown that the development of aminoglycoside-induced renal toxicity increases the cost per patient per course of therapy by $2,500. Even in patients in whom nephrotoxicity does not develop as a consequence of aminoglycoside therapy, renal function tests, serum drug concentration monitoring, and consultations add an additional $620 to the hospital bi11.4 Aztreonam has a spectrum of antimicrcbial activity that consists exclusively of aerobic gram-negative pathogens. Thus, the in vitro activity of aztreonam resembles that of the aminoglycosides. 5 High concentrations are achieved in the urine and renal tissues, and aztreonam is a remarkably safe ant:ibiotic. :Empiric therapy with aztreonam for infectio:ns, such as pneumonia or intra-abdominal. infection, requires administration with1 other antibiotics that have activity against anaerobes and gram-positive aerobes. However, when the Gram stain of the urine is not suggestive of a gram-positive infection, aztreonam is an appropriate empiric choice for monotherapy of urinary tract infections caused by susceptible gram-negative aerobic pathogens. Historical Background The discovery of a new class of naturally occurring compounds with antimicrobial activity was reported independently in the early 1980s by two separate teams of investigatorse17 These agents were named monobactams because they were derived from monocyclic P-lactams produced by bacteria. 8 Structural modifications, which were necessary to improve the relatively poor in vitro activity of the natural monobactams, resulted in the development of aztreonam (Fig. 1). The sulfonic acid group at position 1 activates the @-lactam ring. The a-methoxy

UROLOGY

MARCH

1993

VOLUME

41, NUMBER 3

249

FIGURE1. Chemical activity relationships from Ma&en PO, et

configuration and structureof aztreonam (reproduced al.,51 with permission).

group at position 4 increases antibacterial activity and also provides stability to P-lactamases. The aminothiazole oxime group at position 3 is responsible for activity against gram-negative aerobes. Increased activity against Pseudomonas is attributed to the presence of a carboxyl group at this position.e-ll Antimicrobial Activity

Aztreonam is a bactericidal antibiotic with a mechanism of action that is similar to the penicillins and cephalosporins. Aztreonam inhibits the bacterial cell-wall synthesis of gram-negative bacteria by binding preferentially to penicillin-binding protein (PBP)-3. Aztreonam does not bind the PBP found in gram-positive or anaerobic bacteria, which accounts for the narrow spectrum of activity of this agent. After binding to PBP-3, aztreonam causes elongation or filamentation, holes in the cell wall, cell lysis, and cell death.i2 Aztreonam is highly stable to the P-lactamases produced by gram-negative and gram-positive organisms. 13,14 Aztreonam possesses in vitro activity against gram-negative aerobic uropathogens, including

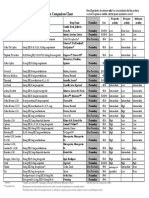

TABLE I. Oganism

most Enterobacteriaceae and many Pseudomonas species (Table I). Established susceptibility breakpoints for aztreonam with agar or broth dilution techniques are 18 PglmL (susceptible), 16 pg/mL (intermediate), and 132 pg/mL (resistant). Inhibition zones using the KirbyBauer disk diffusion technique (with a disk containing 30 pg of aztreonam) are 222 mm (susceptible), 16 to 22 mm (moderate), and 515 mm (resistant). l5 Aztreonam demonstrates minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) that are equal to, or twofold or fourfold greater than, the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for susceptible strains of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Morganella morganii, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens, and P aeruginosa. 16-l The inhibitory concentrations for most Enterobacteriaceae are well below achievable concentrations of aztreonam in the urine, renal parenchyma, and prostate.lE21 When tested in vitro against clinical isolates from patients with complicated or nosocomial urinary tract infectionsle or a variety of other infections,1eT22-24 most strains of Enterobacteriaceae are inhibited by concentrations of aztreonam that are less than or equal to 1.6 PglmL. Higher concentrations are needed for inhibition of Enterobacter species and I? aeruginosa. The activity of aztreonam against gram-negative aerobes is therefore similar to that of the third-generation cephalosporins. However, aztreonam possesses no activity against gram-positive organisms or anaerobic organisms. Thus, the microbiologic activity of aztreonam is unique among /3-lactam agents and is similar to the anti-aerobic, gramnegative spectrum of aminoglycosides.

and third-generation cephalosporins *

Cefoperazone >lOO >lOO 100 >lOO > 100 2.4 5.8 10.7 6.3 > 100 4.7 0.2 6.0

In vitro activity of axtreonam

Aztreonam 0.2 0.3 12.5 33.3 1.6 <O.l <O.l <O.l 0.6 <O.l ::: 12.0

(No. of Strains)

E. coli (79) K. pneumoniae (68) E. cloacae (29) E. aerogenes (13) S. marcescens (113) F! mirabilis (25) P. vulgaris (11) P. rettgeri (6) l? morganii (19) F! stuartii (15) C. freundii (25) N. gonorrhoeae (20) l? aeruginosa (61)

Cefotaxime 0.2 0.3 25.0 42.9 8.4 <O.l 5.5 0.2 1.6 3.0 0.4 <O.l NA

MIGo (pglmL) Ceftazidime 0.4 1.1 12.5 >lOO 1.5 0.1 <O.l 2.3 3.1 4.7 2.0 <O.l 3.0

KEY: NA = not applicable. *Adapted from SykesRB, et al. ,24 with permission.

250

UROLOGY

MARCH 1993

VOLUME 41, NUMBER

TABLE

II. Pharmacokinetic parameters aztreonam in healthy volunteers

Parameter cont. (IV)

of

Mean Value 38.7 pg/mL 99.5 pg/mL 242 PglmL

Peak serum 0.5 g lg 2g Peak serum 0.5 g

cont.

(IM) 18.2 PglmL 36.1 pg/mL (IM) lh lh 1.7 h 0.21 L/kg 89 mL/min 66 mL/min 56% 600%74% FIGURE 2. Mean urinary concentrations of aztreonam (pg/mL) after intravenous and intramuscular administration in healthy volunteers.31

lg Time to peak serum cont. 0.5 g

lg Elimination half-life (IV) Volume of distribution (IV) (steady state) Clearance (IV) Plasma Renal Protein binding (IV) 24-hour urinary recovery (IV)

KEY: IV = intravenous;

IM = intramuscular.

Because of its fl-lactam structure, hydrolysis by fl-lactamases is the most important means of bacterial resistance to aztreonam.25 Aztreonam is stable to hydrolysis by most plasmid-mediated fl-lactamases from E. coli and F! aeruginosa and chromosomally mediated enzymes from C. freundii, E. cloacae, E. coli, M. morganii, Providencia species, Serratia species, and I? aeruginosa. Some fl-lactamases, particularly Kl and SHV-5 from Klebsiella species and the PSE-2 from I?. aeruginosa are able to hydrolyze aztreonam, resulting in microbial resistance to these strains. 17,26*27 Unlike some other plactam antibiotics (e.g., cefoxitin), aztreonam has not been shown to induce the production of chromosomally mediated fl-lactamases in E. cloacae and M . morganii.28 Pharmacokinetics

Absorption and distribution

Less than 1 percent of an administered dose of aztreonam is absorbed following oral administration.2e Thus, aztreonam is given exclusively via parenteral administration. Aztreonam is rapidly absorbed following intramuscular administration. Peak serum concentrations of 18.2 pg/mL and 36.1 pg/mL are attained within one hour of single intramuscular doses of 0.5 g and 1 g, respectively. Peak serum concentrations were 38.7 PglmL, 99.5 pg/mL, and 242 PglmL following three-minute intravenous infusions of 0.5 g, 1 g,30 and 2 g,31 respectively (Table II). Mean serum concentrations c

UROLOGY

twelve hours after a l-g dose were 0.65 PglmL (intramuscular administrations) and 0.51 pgl mL (intravenous administration) .31 Therapeutic doses of 0.5 g and 1 g result in high and sustained urinary concentrations of aztreonam (Fig. 2). Urine concentrations are ten-fold to one hundred-fold greater than concurrent serum concentrations. Peak urine concentrations after a l-g intravenous dose are 3,000 pg/mL; urinary concentrations twelve hours after the dose are 11 pg/mLa31 In general, urine concentrations of aztreonam greatly exceed the MICso values for most gram-negative uropathogens for at least twelve hours after the dose. The pharmacokinetic properties of aztreonam can be characterized by a two-compartment, open, linear model. The mean elimination half-life is 1.7 hours and the volume of distribution at steady state is 0.21 L/kg, which approximates total extracellular fluid volume.30 In healthy volunteers, approximately 56 percent of an administered dose of aztreonam is bound to plasma proteins (Table II). 3o These parameters are similar to many penicillins and cephalosporins. 32*33 Aztreonam distributes to various body fluids, including peritoneal fluid,= blister fluid 35 cerebrospinal fluid,3e aqueous humour, bronchial secretions,38 bile, and breast milk.3e The concentrations of aztreonam also have been measured in human prostate tissue18,21 and in renal tissue from postnephrectomy patients (Table III).2o Prostate tissue was obtained from men undergoing transurethral resection following single l-g intravenous doses of aztreonam. m21 The mean aztreonam concentrations in prostate tissue between fifty and one hundred eighty minutes after the dose were

MARCH 1993

/ VOLUME 41, NUMBER 3

251

TABLE III. Diagnosis (N) Renal tissue Severe renal disease Transplant rejection (1) Transplant rejection (1) Transplant rejection (1) Transplant rejection (1) Chronic glomerulonephritis Chronic glomerulonephritis Polycystic (1) Chronic pyelonephritis (1)

Aztreonam concentrations in serum, renal tissue, and prostate1ae1

Serum Cont. (pg/mL) -Tissue Cortex Conc~~;a~ns (cg/g)Papilla

(1) (1)

52 43 162 108 101 90 156 141 68 62 111 86

R L R L R L R L

27 50 70 16 51 36 62 61 4.6 5.7 83 66

31 49 62 32 62 46 74 60 . . ii . .

34 57 103 25 63 51 60 77 . . ii 73

Prostate tissue Benign hypertrophy Benign hypertrophy

(8) (10)

31 38

7.8 6

7.P and 6 pg/g tissue.21 The mean prostate: serum concentration ratio was 0.25 and exceeded the MIC values for most Enterobacteriaceae that cause chronic prostatitis. * The postnephrectomy findings from 8 patients with severe renal disease demonstrate that intrarenal aztreonam concentrations (i.e., 16 pglg to 103 pg/g) are somewhat lower than simultaneous serum concentrations (i.e., 43 PglmL to 162 PgI mL), but are higher than the MIC& values of susceptible gram-negative uropathogens.20 Metabolism and excretion Aztreonam is excreted unchanged in the urine by both glomerular filtration and tubular secretion.40,41 The renal clearance of aztreonam is 66 mllmin, and 60 percent to 74 percent of an administered dose is excreted in the urine after twenty-four hours (Table II).3o,35 A minor proportion of the dose (1% ) is excreted unchanged in the feces. A microbiologically inactive metabolite accounts for an additional 7 percent of urinary and 3 percent of fecal excretion.42 The elimination half-life of 1.7 hours in healthy subjects is prolonged to 2.2 hours in patients with biliary cirrhosis and 3.2 hours in alcoholics.43 Pharmacokinetics in special populations The pharmacokinetic properties of aztreonam have been described in normal volunteers,31,35 healthy elderly volunteers,10 patients with renal failure,44,45 hematologic ma43 lignancies, 48 alcoholic cirrhosis 9 infections,34x47

Time (h)

FIGURE 3. Urinary concentrations (mean f SD) and cumulative urinary excretion (% of dose injected) in 9 elderly patients after a single l-g intravenous dose of axtreonam (reproduced from Naber KG, et al., with permission). O

and thermal injury. 48 Because of minimal metabolism and predominant urinary elimination, the pharmacokinetic properties of aztreonam are most affected by renal impairment.40 Pharmacokinetics in the elderly. The elimination half-life of aztreonam in elderly individuals is prolonged from 1.7 to 2.7 hours.lg However, approximately 70 percent of an administered dose is excreted in the urine in twelve hours9 (Fig. 3) and serum concentrations associated with equivalent doses are not higher in elderly versus younger patients.4g Dosage adjustments based solely on advanced age are, therefore, not necessary. Pharmacokinetics in renal dysfunction. The elimination half-life of aztreonam increases to six hours and the renal clearance decreases to

252

UROLOGY

/ MARCH1993

/ VOLUME41,NUMBER3

29 mL/min in anephric patients. There is no change in the volume of distribution, but the hypoproteinemic state that is associated with renal failure reduces protein binding to 36 percent. Thus, serum concentrations of free and pharmacologically active antibiotic (i.e., that portion of the dose that is not bound to plasma proteins) are somewhat increased.45 Pharmacokinetics in renal dialysis. A fourhour hemodialysis session in 6 anephric patients increased mean aztreonam plasma clearance from 24 mL/min to 40 mL/min and decreased elimination half-life from 7.9 to 2.7 hours. Hemodialysis removed approximately 40 percent of the administered dose of aztreonam.44 Thus, half of the aztreonam dose should be given at the conclusion of hemodialysis. Chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis increased aztreonam plasma clearance by less than 10 percent when the dose was administered intravenously. Dialysate concentrations of 105 pg/mL were achieved six hours following an intraperitoneal dose of 1 g; measurable drug concentrations persisted for forty-eight hours after the dose despite 8 dialysate exchanges,44 which suggests that the intraperitoneal route of administration may be of use in these patients. Clinical Use in Urology Clinical experience with aztreonam is extensive, and urinary tract infections represent the most frequent types of infection that are treated with this agent. 50-52Pooled data from studies conducted around the world reveal clinical response rates to aztreonam monotherapy for urinary tract infections in excess of 80 percent. 51-53 Aztreonam is effective in the treatment of complicated, uncomplicated, and recurrent urinary tract infections, including pyelonephritis, cystitis, prostatitis, epididymitis, and other types of unspecified urinary tract infections.51,53 As with other antibiotics, therapeutic response depends to a large extent on the presence of complicating factors, such as urologic abnormalities, obstruction, and foreign bodies. Microbiologic cures have been attained in infections caused by I? aeruginosa and Pseudomonas species and various Enterobacteriaceae, including E. coli and Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Serratia, Proteus, Citrobacter, Providencia, Acinetobatter, and Morganella species. 53 Controlled studies have compared aztreonam with second- and third-generation cephalospo-

rins and the aminoglycosides in the treatment of urinary tract infections. The clinical and microbiologic efficacy of aztreonam is comparable to standard therapy with these agents. Cefamandole (1 g three times daily) was compared to aztreonam (0.5 or 1 g twice or thrice daily) in 159 patients with nosocomial urinary tract infection.54 After five to nine days of therapy, pathogens were eradicated from the urine of 87.5 percent of patients treated with aztreonam three times daily. This response was slightly greater than that attained in the aztreonam twice-daily (82.7 %) or cefamandole (78.3 %) groups. Relapse, reinfection, and superinfection in patients treated with aztreonam were most commonly caused by Enterobacteriaceae (i.e., E. coli, Klebsiella species, and Citrobacter species). I? aeruginosa was the most common cause of treatment failure among patients treated with cefamandole. Aztreonam also has been shown to be as effective as cefotaxime19 and cefuroxime55 in hospitalized patients with complicated urinary tract infections. In one series, aztreonam (1 g twice daily) was compared with cefotaxime (1 g twice daily) in the treatment of 39 adult urologic patients with complicated and/or nosocomial urinary tract infections.lg The initial infecting pathogens were eradicated in all patients in the aztreonam group and in 19 of 20 cefotaxime patients; complete cures were attained in approximately one third of patients in both groups. However, one to two days after completing therapy, 16 percent of aztreonam patients and 10 percent of cefotaxime patients had significant bacteriuria. At follow-up one to four weeks later, superinfections (3 for aztreonam; 1 for cefotaxime), relapses (7 for aztreonam; 6 for cefotaxime), and reinfections (3 for aztreonam; 5 for cefotaxime) had occurred in both treatment groups. Enterococci were associated with reinfection, particularly in postoperative patients. In another series, aztreonam (1 g three times daily) produced comparable clinical (89 % versus 87 % ) and microbiologic cures (70 % versus 73 % ) as cefuroxime (1.5 g three times daily) .55 Aztreonam has been compared with aminoglycoside therapy and is as effective as gentamicin, 56,57tobramycin,5s,59 or amikacin58 in patients with urinary tract infections. Sattler and colleagues 57 demonstrated that aztreonam was as effective and may be less toxic than gentamicin in 52 hospitalized patients with serious urinary tract infections. Most patients achieved

UROLOGY

MARCH

1993

/ VOLUME

41, NUMBER 3

253

unequivocal clinical cures (66 % aztreonam; 53 % gentamicin), cures with relapse (17 % aztreonam; 6 % gentamicin), or cures with reinfection (17 % aztreonam; 24 % gentamicin) . (Cure rates between treatment groups were not significantly different.) Side effects that were associated with aztreonam therapy were limited to injection-site phlebitis (1 patient), bad taste (1)) Candida vaginitis (1)) and asymptomatic hepatic function test abnormalities (7), but 4 patients in the gentamicin group experienced significantly elevated serum creatinine concentrations (p = 0.009). Enterococcal superinfection was more common in the aztreonam group. In vitro susceptibility studies revealed that isolates of I? aeruginosa, E. coli, and S. marcescens that were resistant or moderately susceptible to gentamicin were sensitive to aztreonam. Prostatitis Aztreonam penetrates into prostate tissue1*s21 and has been shown to be effective in the treatment of prostatitis, including infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria.53,80 In an open study of 16 patients with prostatitis, aztreonam therapy resulted in favorable clinical responses (100% of 16 patients) and microbiologic cures (81%) .53 Larger, comparative studies are needed before the place of aztreonam in the treatment of prostatitis is determined. Multidrug-resistant pathogens

P aeruginosa infection is common in patients with complicated urinary tract infections, especially in those who have received multiple courses of antibiotics. In the series by COX,~O unqualified cure (i.e., without relapse or superinfection) of urinary tract infections caused by multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas occurred in 96 percent of 55 patients, When data from open and controlled clinical studies involving 681 patients with urinary tract infections were pooled, aztreonam therapy resulted in clinical and microbiologic cure rates of 98 percent and 76 percent, respectively, in 112 patients infected with F! aeruginosa. 53 Pseudomonal superinfections occur more often in patients treated with cefamandole or aminoglycosides than during aztreonam therapy. In contrast, aztreonam is more commonly associated with staphylococcal and enterococcal superinfections. 51+31 Dosage of axtreonam in urologic infections Aztreonam may be administered intramuscularly or intravenously in doses of 0.5 or 1 g every eight or twelve hours for most urinary tract infections in the adult population. Serious infections (e.g., pyelonephritis with bacteremia) or those caused by less susceptible organisms (e.g., I? aeruginosa) may require more aggressive treatment with intravenous doses of up to 2 g every six to eight hours. Patients with hepatic dysfunction do not require dosage adjustment; however, dosage adjustments are needed in patients with renal impairment. Aztreonam clearance correlates directly with adjusted creatinine clearance. This observation, together with the pharmacokinetic changes associated with renal dysfunction, form the basis for dosage adjustment in patients with systemic disease. Patients with normal renal function (e.g., creatinine clearances of 100 mL/min) would receive 0.5 g or 1 g every eight or twelve hours for urinary tract infections. Higher and/or more frequent doses are appropriate for severe or systemic infections (i.e., 1 g or 2 g every 6 or 8 hours). The maintenance dose of aztreonam for patients with moderate renal impairment (e.g., creatinine clearances of approximately 30 mL/min) should be halved after the administration of an initial loading dose of 1 g or 2 g.e2 Anephric or hemodialysis patients should receive an initial loading dose of 0.5 g or 1 g followed by maintenance doses administered after dialysis that are 25 percent of the loading dose. Old age alone is not cause for dosage adjustment. However, renal function as

Aztreonam has been evaluated in the treatment of urinary tract infections caused by organisms that are resistant to multiple antibiotics.53,s0 In one study, 135 patients with urinary tract infections that were complicated by multidrug-resistance and obstruction, genitourinary tract malignancy, neurogenic disease, renal calculi, or chronic pyelonephritis were treated with aztreonam.eO To be eligible for this study, the pathogen had to demonstrate resistance on disk diffusion to ampicillin and firstand second-generation cephalosporins, with or without resistance to the aminoglycosides. The study regimens consisted of aztreonam 1 g three times a day (40 patients) or 0.5 g twice daily (95 patients). The most common pathogen in the two dosage groups was F! aeruginosa. E. coli, Serratia, Morganella, and Providencia species were also very commonly isolated. Clinical cures were attained in 98 percent and 96 percent of patients in the 1 g three-times-daily and the 0.5 g twice-daily groups, respectively.e0

254

UROLOGY

/ MARCH

1993

VOLUME

41, NUMBER 3

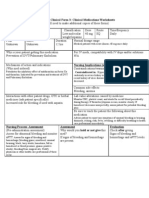

TABLE IV.

Adverse effects of axtreonam therapy*

Effect Incidence 1.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 1.0 0.6 0.2 0.3 0.1 1.9 0.2 0.1 0.2 0.07 0.04 0.09 0.4

Adverse

( %)

Dermatologic (1.8 % ) Rash Rash with eosinophilia Pruritus Purpura Gastrointestinal (2.2%) Diarrhea Nausea/vomiting Taste alteration Clostridium difficile colitis Jaundice/hepatitis Thrombophlebitis Central nervous system (0.5 %) Headache Dizziness Other Miscellaneous Drug fever Hypersensitivity Bleeding Other

*Adapted from Chartrand SA,B3 with permission.

determined by creatinine clearance is a primary determinant of dosage adjustment in elderly patients, l8 and higher doses may be needed in patients with severe burn injury.48 Safety of axtreonam The adverse-effect profile of aztreonam in the general adult, elderly, and pediatric populations49,63,64 and in patients with urinary tract infectionP has been extensively reviewed. Adverse reactions occur in 7 percent of patients and are serious enough to require discontinuation of therapy in 2 percent of patients.e4 A review of pooled findings from published studies and data from the manufacturer in over 4,500 adults83 reveals a low incidence of adverse effects (Table IV). Rash, which occurred in less than 2 percent of patients, was the most commonly reported adverse effect. Diarrhea was reported by 1 percent of patients. Individual central nervous system effects occurred in fewer than 0.5 percent of patients, and none had seizures that were related to aztreonam therapy. Aztreonam does not contain the Nmethylthiotetrazole group and does not alter the anaerobic bowel flora; therefore bleeding diatheses do not occur during therapy. The spectrum of laboratory abnormalities associated with aztreonam therapy is similar to therapy with cefamandole and the aminoglycosides. A notable exception is the relatively greater incidence of elevated serum creatinine

concentrations that are associated with aminoglycoside therapy as compared with aztreonam. The findings of comparative studies of aztreonam and aminoglycosides in patients with urinary tract infections or lower respiratory tract infections were evaluated for marked deviations in serum creatinine concentrations. Marked deviations in serum creatinine concentrations were defined as an increase of 20.5 mg/dL in patients with baseline values of < 3.0 mg/dL or an increase of 2 1.0 mg/dL when baseline values were 2 3.0 mg/dL. Aminoglycoside therapy was associated with markedly elevated serum creatinine in 9 percent of 121 patients, in 5 of whom azotemia also developed. In contrast, 4 percent of 275 aztreonam-treated patients exhibited elevated serum creatinine concentrations and none became azotemic.e4 The lack of renal toxicity associated with aztreonam was confirmed in a study of 11 patients with urinary tract infections. Evaluation of renal function tests and concentrations of urinary enzymes before, during, and after a five-day course of therapy revealed no clinically significant adverse effects on renal function.e5 When the dose is adjusted according to creatinine clearance, aztreonam can be safely administered to patients with renal insufficiency,ea including the elderly.49 Sion and colleagues 66 treated 39 patients (25 with chronic and 14 with acute renal failure) with a variety of gram-negative infections (22 urinary tract infections) with aztreonam. Adverse effects were limited to transient elevations in serum transaminases (4 patients) and intramuscular injection-site reactions (5 patients). Renal function improved in this population as demonstrated by mean reductions in serum creatinine concentrations from 3.79 f 2.84 mg/dL (baseline) to 3.30 f 2.52 mg/dL (end of therapy; ~~0.003). Clinically significant changes in laboratory test values during aztreonam therapy are uncommon. Aztreonam therapy was associated with three-fold increases in hepatic transaminases in 27 of 2,388 patients from a pooled database. Elevated liver enzymes resolved spontaneously in 21 of the 27 patients and were not judged to be related to aztreonam therapy in 5 others. Adverse clinical effects or abnormal laboratory test findings resulted in premature discontinuation of aztreonam therapy in 2 percent of 2,388 patients because of rash or other dermatologic reaction (nearly half of patients), abnormal liver function tests (10 patients), or other reactions. In comparative studies, the

UROLOGY

MARCH 1993

VOLUME

41, NUMBER 3

25s

discontinuation of aztreonam therapy because of adverse effects or laboratory test abnormalities occurred at the same rate as in cefamandole or aminoglycoside therapy (1.7 percent versus 1.5 percent, respectively). 64 The possibility of cross-reactions in patients who are allergic to penicillins or cephalosporins is of potential concern with the use of agents possessing a /3-lactam ring structure (e.g., aztreonam). However, the findings from reviews of clinical experience in the general population8~51~67-0e and studies designed to assess its immunogenic potential in penicillin-allergic individuals70-74 indicate that aztreonam therapy presents minimal risk of hypersensitivity reactions. Fewer than 1 percent of persons with documented allergy to penicillins and cephalosporins exhibited possible hypersensitivity reactions to aztreonam. 7o-72,74 Antibodies produced in rabbits in response to penicillin G, including immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies to major and minor determinants, and cephalothin were not cross-reactive with aztreonam, which suggests that aztreonam may be safely administered to patients who are allergic to penicillin On and the cephalosporins . Summary Extensive clinical experience supports the use of aztreonam in the treatment of serious urinary tract infections. This monobactam possesses a spectrum of activity similar to the aminoglycosides yet without their toxic effects. Usual therapeutic doses of 0.5 or 1 g achieve concentrations in the blood, renal parenchyma, prostate tissue, and urine that exceed the minimum inhibitory concentrations of most gramnegative uropathogens. Intravenous doses of 2 g administered every eight hours are needed for infections caused by I? aeruginosa. Comparative clinical studies of adults with serious and/or complicated aerobic, gram-negative urinary tract infections have demonstrated that monotherapy with aztreonam is as effective as cephalosporins and aminoglycosides. Aztreonam is remarkably well tolerated. The most commonly reported adverse reactions are rash and diarrhea, which are mild, fully reversible, and have generally not been severe enough to require discontinuation of therapy. Aztreonam does not cause renal toxicity and may be administered to patients with penicillin allergy. Thus, aztreonam represents rational therapy for patients with complicated/severe urinary

TABLE V. Urologic Infection

Urologic uses of aztreonam Empiric Monotherapy Combination Therapy

Acute cystitis (gramnegative bacilli in compromised hosts) Acute prostatitis Young patient Elderly patient Acute epididymitis Young patient Elderly patient Acute pyelonephritis Urosepsis Postinstrumentation

+ + +

NA NA Add ampicillin if enterococci present Add doxycycline for Chlamydia NA NA

+ +* +

+ * Add ampicillin if enterococci present Nonleukopenic compromised host (diabetic, lupus, immunosuppressive therapy) +* NA Abnormal anatomy/ obstetric + Add ampicillin if enterococci present

KEY: NA = not applicable. aeruginosa is a common pathogen in these settings. Specific P therapy should be guided by susceptibility testing. If P aeruginosa resistance to aztreonam is a problem, initial empiric therapy with amikacin would be preferable.

tract infections. Aztreonam may be used as a single agent when Gram stain of the urine indicates the presence of a gram-negative pathogen. However, when gram-positive organisms (e.g., enterococci) are present, an antibiotic that covers these organisms should be used instead or added to the therapeutic regimen (Table V).

Infectious Disease Division Winthrop-University Hospital Mineola, New York 11501 References

1. Platt R: Diagnosis and empiric therapy of urinary tract infection in the seriously ill patient, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl 1) 5: S65 (1983). 2. Bryan CS, and Reynolds KL: Hospital-acquired bacteremic urinary tract infection: epidemiology and outcome, J Urol 132: 494 (1984). 3. Bryan CS, Reynolds KL, and Brenner ER: Analysis of 1,186 episodes of gram-negative bacteremia in nonuniversity hospitals: the effects of antimicrobial therapy, Rev Infect Dis 5: 629 (1983). 4. Eisenberg JM, et al: What is the cost of nephrotoxicity associated with aminoglycosides? Ann Intern Med 107: 900 (1987). 5. Cunha BA: Aminoglycosides in urology, Urology 36: 1 (1990). 6. Imada A, et al: Sulfazecin and isosulfazecin, novel @-lactam antibiotics of bacterial origin, Nature 289: 590 (1981). 7. Sykes RB, et aE: Monocyclic S-lactam antibiotics produced

256

UROLOGY

/ MARCH 1993 / VOLUME 41, NUMBER 3

by bacteria, Nature 291: 489 (1981). 8. Tunkel AR, and Scheld WM: Aztreonam, Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 11: 486 (1990). 9. Bonner DP, and Sykes RB: Structure activity relationships among the monobactams, J Antimicrob Chemother 14: 313 (1984). 10. Breuer H, et al: Monobactams-structure-activity relationships leading to SQ 26,776, J Antimicrob Chemother (Suppl E) 8: 21 (1981). 11. Neu HC: /3-lactam antibiotics: structural relationships affecting in vitro activity and pharmacologic properties, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl 3) 8: S237 (1986). 12. Georgopapadakou NH, Smith SA, and Sykes RB: Mode of action of aztreonam, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 21: 950 (1982). 13. Neu HC: Aztreonam: the first monobactam, Med Clin North Am 72: 555 (1988). 14. Sykes RB, Bormer DP Bush K, Georgopapadakou NH, and Wells JS: Monobactams-monocyclic fi-lactam antibiotics produced by bacteria, J Antimicrob Chemother (Suppl E) 8: 1 (1981). 15. Barry AL, Thornsberry C, Jones RN, and Cavan TL: Aztreonam: antibacterial activity, @lactamase stability, and interpretive standards and quality control guidelines for disk-diffusion susceptibility tests, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl 4) 7: 594 (1985). 16. Neu HC. and Labthavikul P: Antibacterial activitv of a monocyclic 6 lactam SQ 26,776, J Antimicrob Chemother (Suppl E) 8: 111 (1981). 17. Phillips I, King A, Shannon K, and Warren C: SQ 26,776: in vitro antibacterial activity and susceptibility to p-lactamases, J Antimicrob Chemother (Suppl E): 8: 103 (1981). 18. Madsen PO, Dhruv R, and Friedhoff LT: Aztreonam concentrations in human prostatic tissue, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 26: 20 (1984). 19. Naber KG, et al: Pharmacokinetics, in vitro activity, therapeutic efficacy, and clinical safety of aztreonam vs cefotaxime in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections, J Antimicrab Chemother 17: 517 (1986). 20. Watson AJS, Stout RL, and Whelton A: The intrarenal distribution of aztreonam in healthy and diseased kidneys: clinical therapeutic implications, J Infect Dis 150: 631 (1984). 21. Whitby M, et al: Penetration of monobactam antibiotics (aztreonam, carumonam) into human prostatic tissue, Chemotherapy 35: 7 (1989). 22. Jacobus NV, Ferreira MC, and Barza M: In vitro activity of aztreonam, a monobactam antibiotic, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 22: 832 (1982). 23. Reeves DS, Bywater MJ, and Holt HA: Antibacterial activity of the monobactam SQ 26,776 against antibiotic resistant enterobacteria, including Serratia sp, J Antimicrob Chemother (Suppl E) 8: 57 (1981). 24. Sykes RB, Bonner DP, Bush K, and Georgopapadakou NH: Aztreonam (SQ 26,776), a synthetic monobactam specifically active against aerobic gram-negative bacteria, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 21: 85 (1982). 25. Dever LA, and Dermody TS: Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, Arch Intern Med 151: 886 (1991). 26. Cutmann L, et al: SHV-5, a novel SHV-type fl-lactamase that hydrolyzes broad-spectrum cephalosporins and monobactams, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33: 951 (1989). 27. Zurenko GE, et al: In vitro antibacterial activity and interactions with fi-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins of the new monocarbam antibiotic U-78608, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34: 884 (1990). 28. Sykes RB, and Bonner DP: Discovery and development of the monobactams, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl4) 7: S579 (1985). 29. Swabb EA, Sugerman AA, and Stern M: Oral bioavailability of the monobactam aztreonam (SQ 26,776) in healthy subjects, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 23: 548 (1983). 30. Swabb EA, Sugerman AA, and McKinstry DN: Multipledose pharmacokinetics of the monobactam aztreonam (SQ 26,776) in healthy sbjects, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 23: 125 (1983).

31. Swabb EA, et al: Single-dose pharmacokinetics of the monobactam aztreonam (SQ 26,776) in healthy subjects, Antimicrab Agents Chemother 21: 944 (1982). 32. Barza M, and Weinstein L: Pharmacokinetics of the penicillins in man, Clin Pharmacokinet 1: 297 (1976). 33. Bergan T: Pharmacokinetic properties of the cephalosporins, Drugs (Suppl 2) 34: 89 (1987). 34. Winslade NE, et al: Pharmacokinetics and extravascular penetration of aztreonam in patients with abdominal sepsis, Rev Infec Dis (Suppl 4) 7: 716 (1985). 35. Wise R, Dyas A, Hegarty A, and Andrews JM: Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of aztreonam, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 222: 969 (1982). 36. Greenman RL, et al: Penetration of aztreonam into human cerebrospinal fluid in the presence of meningeal inflammation, J Antimicrob Chemother 15: 637 (1985). of aztieonam in the 37. Haroche G, et al: Pharmacokinetics aqueous humour, J Antimicrob Chemother 18: 195 (1986). 38. Bechard DL, Hawkins SS, Dhruv R, and Friedhoff LT: Penetration of aztreonam into human bronchial secretions, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 27: 263 (1985). 39. Stutman HR: Aztreonam: clinical pharmacology, Pediatr Infect Dis J 8: S104 (1989). 40. Mattie H: Clinical pharmacokinetics of aztreonam, Clin Pharmacokinet 14: 148 (1988). 41. Swabb EA, et al: Renal handling of the monobactam aztreonam in healthy subjects, Clin Pharmacol Ther 33: 609 (1983). and pharmacokinetics of 42. Swabb EA, et al: Metabolism aztreonam in healthy subjects, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 24: 394 (1983). 43. MacLeod CM, et al: Effects of cirrhosis on kinetics of aztreonam, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 26: 493 (1984). 44. Gerig JS, et al: Effect of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis on aztreonam pharmacokinetics, Kidney Int 26: 308 (1984). 45. Mihindu JCL, et al: Pharmacokinetics of aztreonam in patients with various degrees of renal dysfunction, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 24: 252 (1983). 46. Jones PG, et al: Clinical pharmacokinetics of aztreonam in cancer patients, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 26: 455 (1984). 47. Janicke DM, et al: Pharmacokinetics of aztreonam in patients with gram-negative infections, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 27: 16 (1985). 48. Friedrich LV, et al: Aztreonam pharmacokinetics in burn patients, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35: 57 (1991). 49. Sattler FR, Scbramm M, and Swabb EA: Safety of aztreonam and SQ 26,992 in elderly patients with renal insufficiency, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl 4) 1: S622 (1985). 50. Bosso JA, and Black PG: The use of aztreonam in pediatric patients: a review, Pharmacotherapy 11: 20 (1991). 51. Madsen PO, Nielsen KT, and Craversen PH: Aztreonam: critical evaluation of the first monobactam antibiotic in treatment of urinarv tract infections. 1 Urol 140: 925 0988). 52. Stutman HR: Clinical experience with aztreonam, Pediatr Infect Dis J (Suppl 9) 8: S109 (1989). 53. Swabb EA, Jenkins SA, and Muir JG: Summary of worldwide clinical trials of aztreonam in patients with urinary tract infections, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl4) 7: 772 (1985). 54. Childs S: Aztreonam in the treatment of urinary tract infection, Am J Med (Suppl 2A) 78: 44 (1985). comparison of aztreonam 55. Friman G, et al: Randomized and cefuroxime in gram-negative upper urinary tract infections, Infection 17: 284 (1989). 56. Albertazzi A, et al: Multicenter comparative study of aztreonam and zentamicin in the treatment of renal and urinarv tract infections,-Chemotherapy (Suppl 1) 35: 77 (1989). 57. Sattler FR, et al: Aztreonam compared with gentamicin for treatment of serious urinary tract infections, Lancet 1: 1315 (1984). 58. DeMaria A Jr, et al: Randomized clinical trial of aztreonam and aminoglycoside antibiotics in the treatment of serious infections caused by gram-negative bacilli, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33: 1137 (1989).

UROLOGY

/ MARCH

1993

VOLUME

41, NUMBER

257

59. Fridmodt-Moller PC, and Madsen PO: A comparative study of aztreonam and tobramycin in treatment of complicated urinary tract infections, presented at 13th International Congress of Chemotherapy, Vienna, Austria, 1983. 66. Cox CE: Aztreonam therapy for complicated urinary tract infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria, Rev Infect Dis (Supp14) 7: 767 (1985). 61. Rabinad E, Bosch-Perez A, and Collaborative Study Group: A multicenter comparative trial of aztreonam in the treatment of gram-negative infections in compromised intensive-care patients, Chemotherapy (Suppl 1) 35: 1 (1989). 62. Cunha BA, and Friedman PE: Antibiotic dosing in patients with renal insufficiency or receiving dialysis, Heart Lung 17: 612 (1988). 63. Chartrand SA: Safety and toxicity profile of aztreonam, Pediatr Infect Dis I 8: S120 (1989). 64. Newman TJ, Dreslinski GR, and Tadros SS: Safety profile of aztreonam in clinical trials, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl 4) 7: S648 (1985). 65. Donadio C, et al: Aztreonam in the treatment of urinary tract infection: evaluation of efficacy, renal effects, and nephrotoxicity, Drugs Exp Clin Res 13: 167 (1987). 66. Sion ML, et al: Efficacy and safety of aztreonam in the treatment of patients with renal failure, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl7)

13: s652 (1991). 67. Daikos GK: Clinical experience with aztreonam in four Mediterranean countries, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl 4): 7: S831 (1985). 68. Hara K, et al: Clinical studies of aztreonam in Japan, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl4) 7: S810 (1985). 69. Stille W, and Gillissen J: Clinical experience with aztreonam in Germany and Austria, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl4) 7: S825 (1985). 70. Adkinson NF Jr, Saxon A, Spence MR, and Swabb EA: Cross-allergenicity and immunogenicity of aztreonam, Rev Infect Dis (Suppl 4) 7: S613 (1985). 71. Adkinson NF Jr, Swabb EA, and Sugarman AA: Immunology of the monobactam aztreonam, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 25: 93 (1984). 72. Henry SA, and Bendush CB: Aztreonam: worldwide overview of the treatment of patients with gram-negative infections, Am J Med (Suppl2A) 78: 57 (1985). 73. Jensen T, Pedersen SS, Hoiby N, and Koch C: Safety of aztreonam in patients with cystic fibrosis and allergy to fl-lactam antibiotics. Rev Infect Dis (SUKJD~ 13: S594 (1991). 7) between 74. Saxon A, et al: LaS of cross-reactivity aztreonam, a monobactam antibiotic, and penicillin in penicillinallergic subjects, J Infect Dis 149: 16 (1984).

258

UROLOGY

MARCH 1993

VOLUME 41, NUMBER 3

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Antimicrobial Therapy in Veterinary MedicineVon EverandAntimicrobial Therapy in Veterinary MedicineSteeve GiguèreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Adult Infectious Disease Bulletpoints HandbookVon EverandAdult Infectious Disease Bulletpoints HandbookBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (9)

- 22 1-S2.0-S0924857908002392-MainDokument3 Seiten22 1-S2.0-S0924857908002392-MainLookpear ShiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Current Senerio of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates in East Uttar Pradesh, IndiaDokument4 SeitenCurrent Senerio of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates in East Uttar Pradesh, IndiaPraveen GautamNoch keine Bewertungen

- CEFACLOR-cefaclor Caps Ule Carls Bad Technology, IncDokument13 SeitenCEFACLOR-cefaclor Caps Ule Carls Bad Technology, IncsadafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Piocianic EsblDokument15 SeitenPiocianic EsblMari FereNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aminoglycoside: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument11 SeitenAminoglycoside: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaawajahat100% (3)

- Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy-2016-Oshima-e02056-16.fullDokument9 SeitenAntimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy-2016-Oshima-e02056-16.fullI Made AryanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claforan (Cefotaxime) PDFDokument18 SeitenClaforan (Cefotaxime) PDFdinniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14 Antibiotik Dan Antiseptik Untuk IskDokument40 Seiten14 Antibiotik Dan Antiseptik Untuk IskSintaKleoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aminoglycoside Antibiotics in Infectious Diseases. An Overview PDFDokument13 SeitenAminoglycoside Antibiotics in Infectious Diseases. An Overview PDFjoadascouvesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter OneDokument17 SeitenChapter OneBrix RosalijosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aminoglycoside: Systemic AminoglycosidesDokument47 SeitenAminoglycoside: Systemic AminoglycosidesPawan PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aminoglycosides: Aminoglycoside Is CategoryDokument6 SeitenAminoglycosides: Aminoglycoside Is CategoryAnonymous RJwbBCkrHNoch keine Bewertungen

- A C A D e M I C S C I e N C e SDokument11 SeitenA C A D e M I C S C I e N C e SWalid EbaiedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feng Lin Et Al, 2022Dokument14 SeitenFeng Lin Et Al, 2022VivianKlembergNoch keine Bewertungen

- AntibioticsDokument53 SeitenAntibioticsMaheen IdreesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paterson Et Al., 2021Dokument3 SeitenPaterson Et Al., 2021Caio Bonfim MottaNoch keine Bewertungen

- S 024 LBLDokument19 SeitenS 024 LBLLAURA DANIELA PIÑEROS PIÑEROSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotic ResistanceDokument32 SeitenAntibiotic ResistanceEmine Alaaddinoglu100% (2)

- 4 C 566 A 70 Da 279 BCFDokument8 Seiten4 C 566 A 70 Da 279 BCFMazin AlmaziniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aminoglucósidos-Nefrotoxicidad en NiñosDokument11 SeitenAminoglucósidos-Nefrotoxicidad en NiñosDaniel Maron Miranda LozanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cefadroxil Drug ProfileDokument17 SeitenCefadroxil Drug ProfileChaudryNomiNoch keine Bewertungen

- DP On AglDokument12 SeitenDP On AglDeepikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antimicrobials RevisionDokument5 SeitenAntimicrobials RevisionDanny LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiple-Antibiotic Resistance Mediated by Plasmids and Integrons in Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella PneumoniaeDokument5 SeitenMultiple-Antibiotic Resistance Mediated by Plasmids and Integrons in Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella PneumoniaeProbioticsAnywhereNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMINOGLYCOSIDESDokument45 SeitenAMINOGLYCOSIDESAbdullah EmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacology 2Dokument8 SeitenPharmacology 2Chariza MayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9 Surgical Infections and Antibiotic SelectionDokument42 SeitenChapter 9 Surgical Infections and Antibiotic SelectionSteven Mark MananguNoch keine Bewertungen

- MalariaDokument13 SeitenMalariaGiska VelindaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Antimicrobial TherapyDokument19 SeitenPrinciples of Antimicrobial TherapyMERVENoch keine Bewertungen

- Cystic FibrosisjgjhvkjDokument9 SeitenCystic FibrosisjgjhvkjDwitari Novalia HaraziNoch keine Bewertungen

- KANAMYCIN - Kanamycin Injection, S Olution Fres Enius Kabi USA, LLCDokument15 SeitenKANAMYCIN - Kanamycin Injection, S Olution Fres Enius Kabi USA, LLCheristiana pratiwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multidrug Resistant On PseudomonasDokument5 SeitenMultidrug Resistant On PseudomonasMinh Nguyen HoangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tratamiento de Infecciones Fúngicas Sistémicas Primera Parte: Fluconazol, Itraconazol y VoriconazolDokument13 SeitenTratamiento de Infecciones Fúngicas Sistémicas Primera Parte: Fluconazol, Itraconazol y VoriconazolKenyi CristianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community-Acquired Urinary Tract InfectionDokument7 SeitenCommunity-Acquired Urinary Tract InfectionAlexander DeckerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modified P.aerugenosaDokument21 SeitenModified P.aerugenosaranjitsinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modified P.aerugenosaDokument21 SeitenModified P.aerugenosaranjitsinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stromectol PiDokument7 SeitenStromectol PiZainul AnwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mi: Mfxnv:Rx1 Mefoxin (Cefoxitin For Injection) 1 G, 2 G and 10 G RX OnlyDokument14 SeitenMi: Mfxnv:Rx1 Mefoxin (Cefoxitin For Injection) 1 G, 2 G and 10 G RX Onlymarvin bangayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- CeftazidimeDokument16 SeitenCeftazidimeNakorn BaisriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotic ClassificationDokument10 SeitenAntibiotic ClassificationRipka_uliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Day 12Dokument2 SeitenDay 12Iiah Adda DiciniieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases Among Isolated Isolated From Blood Culture in A Tertiary Care HospitalDokument4 SeitenPrevalence of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases Among Isolated Isolated From Blood Culture in A Tertiary Care HospitalMohammad K AlshomraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hussain 2018Dokument12 SeitenHussain 2018SHUBHAM SAWANTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibacterial Drugs: B.K. SatriyasaDokument56 SeitenAntibacterial Drugs: B.K. SatriyasaVicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fmicb 12 642541Dokument15 SeitenFmicb 12 642541AsmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Reading Antifungal Treatment For Pityriasis VersicolorDokument22 SeitenJournal Reading Antifungal Treatment For Pityriasis Versicolorelok ainika prautamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- All 2Dokument14 SeitenAll 2Waseem HaiderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aminoglycoside - WikipediaDokument52 SeitenAminoglycoside - WikipediaRustam LoharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mechanisms of ResistanceDokument75 SeitenMechanisms of ResistancedewantarisaputriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotic Resistance Pattern in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Species Isolated at A Tertiary Care Hospital, AhmadabadDokument4 SeitenAntibiotic Resistance Pattern in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Species Isolated at A Tertiary Care Hospital, AhmadabadDrashua AshuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cid/cix182 (Traducido)Dokument35 SeitenCid/cix182 (Traducido)Carlos Manuel Pérez GómezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ceftobiprol Toleranta PDFDokument3 SeitenCeftobiprol Toleranta PDFLavinia RizeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolated From Sputum, Urine and Pus SamplesDokument6 SeitenAntibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolated From Sputum, Urine and Pus SamplesPutri Nilam SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotic Impregnated Tablets For Screening Esbl and Ampc Beta LactamasesDokument4 SeitenAntibiotic Impregnated Tablets For Screening Esbl and Ampc Beta LactamasesIOSR Journal of PharmacyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cefazolin (Ancef ®) : D5W, NsDokument9 SeitenCefazolin (Ancef ®) : D5W, Nsbabe5606Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1 RP130001 PDFDokument8 Seiten1 RP130001 PDFDiga AlbrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tetracyclines: Mechanism of ActionDokument16 SeitenTetracyclines: Mechanism of Actionammar amerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2JMAA-8-12 - 2015sharma PDFDokument5 Seiten2JMAA-8-12 - 2015sharma PDFAMBS ABMS JMAANoch keine Bewertungen

- ALAXAN Module Part1Dokument30 SeitenALAXAN Module Part1api-19864075Noch keine Bewertungen

- Breast Cancer Staging SystemDokument4 SeitenBreast Cancer Staging SystemGabriella PatriciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prelim List of DrugsDokument20 SeitenPrelim List of DrugsJayson Izon SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contraceptive Comparison ChartDokument1 SeiteContraceptive Comparison ChartdryasirsaeedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health Proposal RevisedDokument7 SeitenMental Health Proposal Revisedapi-316749800Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rao 2017Dokument5 SeitenRao 2017drzana78Noch keine Bewertungen

- Protein-Calories, Malnutrition & Nutritional DeficienciesDokument15 SeitenProtein-Calories, Malnutrition & Nutritional DeficienciesChino Paolo SamsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neonatal Pneumonia Case StudyDokument2 SeitenNeonatal Pneumonia Case StudyAngel Villamor0% (1)

- Dissociative Disorder - Treatment GuidelinesDokument81 SeitenDissociative Disorder - Treatment Guidelinesdvladas100% (1)

- Geriatric AssessmentDokument8 SeitenGeriatric AssessmentSai BondadNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Practical Approach To The Science of Ayurveda - BalkrishnaDokument324 SeitenA Practical Approach To The Science of Ayurveda - BalkrishnaLuiz Felipe Castelo Branco100% (4)

- What Is SkincareDokument9 SeitenWhat Is SkincareSYEDA UROOJ BSSENoch keine Bewertungen

- LovenoxDokument1 SeiteLovenoxKatie McPeek100% (2)

- NCP-Ineffective AirwayDokument5 SeitenNCP-Ineffective Airwayjava_biscocho1229Noch keine Bewertungen

- OET Test 14Dokument10 SeitenOET Test 14shiela8329gmailcomNoch keine Bewertungen

- MebendazolDokument11 SeitenMebendazolDiego SalvatierraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Investigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceDokument38 SeitenInvestigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceUjas PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Solutions For Personality Theories Workbook 6th Edition by AshcraftDokument7 SeitenCase Solutions For Personality Theories Workbook 6th Edition by AshcraftMonikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clough K Oncoplasty BJSDokument7 SeitenClough K Oncoplasty BJSkomlanihou_890233161Noch keine Bewertungen

- 7 - Transactional AnalysisDokument32 Seiten7 - Transactional AnalysisHitesh Parmar100% (1)

- Treatment Options For Cranial Cruciate Ligament RuptureDokument7 SeitenTreatment Options For Cranial Cruciate Ligament RuptureDwi MahdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Grade10 4th QuarterDokument40 SeitenHealth Grade10 4th QuarterYnjel HilarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug StudyDokument5 SeitenDrug StudyColleen De la RosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soul Link PDFDokument8 SeitenSoul Link PDFCr HtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Plan On: Ca OvaryDokument13 SeitenNursing Care Plan On: Ca Ovaryvaishali TayadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- PsmsformsDokument1 SeitePsmsformsapi-261670650Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lac CaninumDokument4 SeitenLac CaninumByron José Cerda PalaciosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bilateral Using MusicDokument11 SeitenBilateral Using Musicmuitasorte9Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wound Management of Venous Leg Ulcer, Hartmann, 2006Dokument47 SeitenWound Management of Venous Leg Ulcer, Hartmann, 2006Karen PinemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Portfolio 2007Dokument2 SeitenProfessional Portfolio 2007api-276072200100% (1)