Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

John Marmysz - 2002 - The Cutting Edge Between Trash Cinema and High Art

Hochgeladen von

Andrea BallatoreOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

John Marmysz - 2002 - The Cutting Edge Between Trash Cinema and High Art

Hochgeladen von

Andrea BallatoreCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Film-Philosophy

Journal | Salon | Portal (ISSN 1466-4615) Vol. 6 No. 8, April 2002

John Marmysz The Cutting Edge Between Trash Cinema and High Art

Joan Hawkins _Cutting Edge: Art-Horror and the Horrific Avant-garde_ Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000 ISBN 0-8166-3414-9 326 pp.

In her book _Cutting Edge: Art-Horror and the Horrific Avantgarde_, Joan Hawkins examines a type of film that is frequently considered to be lacking in artistic, philosophical, and social worth by mainstream critics and scholars. The category of film she is interested in includes titles drawn from pornography, violent horror, exploitation, and other 'body genres'. These body genre films have customarily been excluded from serious critical analysis, the author claims, because of their emphasis on 'affect' over 'intellect'. Since they provoke visceral reactions in members of the audience and directly influence the viewers' somatic condition, Hawkins claims that serious critics have dismissed these films as nothing more than pieces of exploitation or of lowly, trash culture. However, according to Hawkins, the fact that a pornographic film arouses an audience sexually, or that a

splatter film fills an audience with disgust and revulsion, is not sufficient reason to dismiss it altogether. Such films often have merits that go beyond their otherwise base and vulgar qualities.

Hawkins refers to body genre films as examples of 'paracinema', a term which emphasizes the outsider status these films enjoy in relation to the mainstream of moviemaking. Part of what she claims in her book is that paracinematic films serve a political, and not just a bodily purpose, insofar as they challenge the tastes of mainstream culture. In doing so, paracinema rebels against the 'regulation of culture' (31) by the middle class, a group which has traditionally set public standards of decency and good taste. In this manner, body genre films share an affinity with forms of high art whose intended purpose is to challenge taken-forgranted assumptions and to push the boundaries of what is considered socially and aesthetically acceptable.

Hawkins's book is less a work of philosophical argumentation than it is a collection of essays exploring the thematic overlap between low and high culture in films. The most philosophical sections of the book are the first three chapters in which the author draws on the work of Linda Williams, Lawrence W. Levine, Pierre Bourdieu, Susan Sontag, Pauline Kael, Marshal McLuhan, and Mikhail Bakhtin. The remaining five chapters and the conclusion of the book are devoted to analysis and evaluation of particular films that illustrate her main thesis. In examining such films as _Eyes Without A Face_, _The Awful Dr Orlof_, _Faceless_, _Rape_, _Snuff_, _Freaks_, Andy Warhol's _Dracula_ and _Frankenstein_, and finally _The People vs Larry Flint_, Hawkins demonstrates that many films generally considered to be examples of trash cinema actually have a dimension that goes beyond the merely shocking or arousing. Although the entire book is quite engaging, I found the chapter on Jess Franco's films and the chapters on _Rape_ and _Snuff_ to be especially interesting. It is in these sections that Hawkins most successfully illustrates the sort of crossover that sometimes exists between examples of high and low art. She also quite vividly shows that there is a whole spectrum of historical, cultural, and political circumstances that influence such designations. The cultural acceptance of a piece of work as legitimate art

often has less to do with the intrinsic qualities of the piece itself and more to do with the social circumstances into which the piece is delivered.

For instance, in her discussion of the films of Jess Franco, Hawkins explains how the legacy of fascism and the particular artistic traditions of Spain contributed to an atmosphere in which graphic horror films became a sophisticated vehicle for the delivery of subversive political messages. The depiction of 'eroticized violence' (94) became a way for post-war Spanish horror directors not just to titillate audiences, but to comment upon the cruelty and inhumanity of the political state. Lacking a literary tradition of horror, Spanish filmmakers drew inspiration from imagery originating in their country's rich tradition of horrific painting. Artists such as Goya and Velazquez provided visual inspiration for the nasty and rather crude depictions of sex and violence that are commonplace in Spanish horror films. To American audiences, Hawkins tells us, these sorts of depictions are received out of their original context, and so are often interpreted not as examples of art at all, but of lowly, vulgar exploitation. However, within Spain, and among those better prepared to understand the purposes and influences of Spanish horror, these films are viewed as examples of legitimate artistic expression.

This particularly effective example illustrates Hawkins's excellent point that an audience lacking the necessary background information to interpret a film in an educated and informed manner will miss subtleties and nuances that are essential to give any work of art a fair assessment. Film viewing is never a passive undertaking, and the more sophisticated and challenging a film becomes, the less passive an audience can afford to be. Many of the other examples of paracinema that Hawkins refers to throughout her book share the characteristic of being 'difficult' in the sense that they are 'demanding in unexpected ways' (97). In addition to dealing with themes and subject matter that may be unfamiliar to mainstream audiences, the films of the paracinema tend to depict violent and sexual imagery, and are often technically clumsy and cheaply made. These sorts of films may run the risk being dismissed as trash culture, thus, not because they lack social, historical, cultural or aesthetic significance, but because that significance is lost on

an audience unwilling or unable to put the effort into looking past surfaces.

Part of the discussion in _Cutting Edge_ is intended to highlight how class bias colors the attitudes of mainstream audiences and critics. Hawkins tells us that although the lower-classes have a distinctive aesthetic sense of their own, *good taste* is most commonly imposed from the top down, either by the middle- or the upper-classes. Regardless of the fact that both 'trash cinema' and 'art films' commonly violate middle-class standards of decency, Hawkins claims that works appealing to the educated tastes of the upper-classes are much more likely to be accepted as valuable and legitimate by the mainstream than similar works that comes from a lower-class perspective. Hawkins illustrates this sort of class bias in her comparison of the films _Rape_ and _Snuff_. _Rape_, conventionally considered an art film and not a piece of lowly exploitation, was directed by Yoko Ono and John Lennon. The film consists of the seventy-seven minute stalking of a German woman through the streets of London. The most disturbing thing about this piece is that the action depicted in it is real. The cameraman randomly picks out and follows the subject of the film in an unrelenting pursuit that ends with the woman cornered and emotionally traumatized in her own apartment. Despite the questionable morality of the methods used in its production, _Rape_ was financed and directed by recognized artists who offered the film not for mainstream titillation but for the consumption and appreciation of serious art critics. Within this context, _Rape_ garnered notoriety for its social commentary and political message. It was both presented and received as a legitimate and serious 'indictment of mass media' (125). The movie _Snuff_, on the other hand, which *was not* intended for consumption by an educated elite, met with widespread condemnation as immoral pornography in spite of the fact that it is a completely fictional work in which no one is actually injured or victimized. The uproar over this film stemmed from a staged rape and murder sequence tacked on to the end of the movie in order to capitalize on news stories about real-life snuff films. Hawkins points out that the controversy surrounding _Snuff_ had the consequence of focusing at least as much public attention on social issues concerning the politics of the media as _Rape_ did. Yet _Snuff_ is conventionally considered lowly trash cinema while _Rape_ is

considered legitimate art.

In comparing the public reception of both _Rape_ and _Snuff_, Hawkins demonstrates that the designations 'art film' and 'trash cinema' are influenced by factors that go far beyond the actual content of a film or the consequences that it has on critical discourse. Two works, depicting equally disturbing imagery and fostering similar cultural debates on similar issues, may meet with widely different critical reactions simply on the basis of where and to whom they are shown. _Rape_ was exhibited at art museums. _Snuff_ was exhibited at 'grind houses'. The former was, thus, 'coded' by the audience as serious art. The latter was 'coded' by the audience as trash. This is, I think, a sound observation on the part of the author. As I mentioned above, it is important to recognize the central role played by an audience in film interpretation.

Nevertheless, when assessing the aesthetic merits of cinematic works, Hawkins often seems to over-emphasize audience reaction at the cost of under-emphasizing both the intentions of filmmakers and the very *being* of the art works themselves. Certainly Hawkins is correct that the *categorization* of a film as high or low art has much to do with the audience that receives it. However, it is unclear from her account whether or not she thinks that this is the *only* thing involved in establishing the legitimacy of art works. At times she seems to advocate the view that there is no objective distinction to be made between better and worse films, and that all movies are equal in their capacity to be imbued with aesthetic value. This comes out most forcefully in the second chapter of the book where Hawkins even suggests that 'channel surfing' television shows is a potentially avant-garde cinematic experience. 'Channel surfing itself . . . is the domestic version of a mode of viewing that, in an earlier time, was decidedly surreal, that is, avantgarde' (37). This I find somewhat bizarre. I appreciate that Hawkins is here attempting to highlight the active nature of those who choose to flip through channels in order to select the bits and pieces of television programming that they desire to consume. She wants to claim that such viewing is not necessarily 'distracted' but is, rather, an example of active, involved spectatorship. But does this active involvement alone

elevate 'channel surfing' into a form of legitimate art? I tend to think not. By emphasizing the part of the spectator so completely, Hawkins ignores the role that a film (or television) producer's skill, artistry, and intentions play in the creation of the final product. The purposes of those who make films, and the specific content of the films themselves, do not appear to be very important on this view, and so Hawkins's account in _Cutting Edge_ might be read as a suggestion that it is solely up to the viewer to bring meaning and worth to a film. Any low-brow film, the author sometimes seems to suggest, might be given an interesting, deep, and significant interpretation by a viewer, and it is this process of interpretation that elevates the film in question to a higher artistic level. This is the theme that, to me, seems most prominent throughout her book, although she never comes out and unequivocally states it.

On the other hand, however, there are places where Hawkins seems to suggest (but never states outright) just the opposite view. For instance, in the second chapter again, while discussing the propensity of paracinema enthusiasts to collect many versions of the same film, including 'directors cuts' and 'rough director's cuts', Hawkins writes: 'the closer you get to the source (in this case the director), the purer and more unadulterated the goods, the better the high' (49). This passage, instead of emphasizing the viewer's subjective powers of imagination and interpretation, shifts the emphasis towards the film director's vision. Here, the suggestion seems to be that the merits and worthiness of a film rely upon successfully receiving the message imparted to the film by the filmmaker. That message, already lying latent within the very being of the film itself, awaits viewers who are clever and diligent enough to discover it. Here, the interpretive activities of viewers are downplayed and the audience is treated more like a receptacle for the filmmaker's ready-made message.

Thus, it remains unclear whether Hawkins is an objectivist or a subjectivist when it comes to the aesthetic merits of film. Perhaps, as would be most reasonable, she stands somewhere in between these two extremes. But as a reader I'm left with no clear answer on this point and, as it stands, I come away from _Cutting Edge_ unsure of the philosophical foundations underlying Hawkins's largely social and political critique of film. Does the meaning and merit of a visual art

form lie completely in the hands of each individual interpreter of that work? Is there any objective essence that lies in a piece of artwork itself, independent of the viewer? I myself am not sure how to answer these complicated philosophical questions, but I think it would be worthwhile if Hawkins devoted more space to clarifying her own thoughts on these matters and offered more arguments in support of her position, whatever it may be.

My two final and brief criticisms of Hawkins's book center on her techniques of analysis. First of all, the method used by Hawkins to convince us of the value of trash/low culture films is often by way of demonstrating their similarity in content, tone, or style to films that are customarily accepted by critics and scholars as examples of legitimate art. This is ironic since part of the message of _Cutting Edge_ is that trash/low culture films promote an aesthetic sense that is lower- rather than upper-class, and that as such they represent a bottomup rebellion against the top-down imposition of good taste by the upper-class promoters of high art. Alluding to the work of Bakhtin, Hawkins wants to assert that trash/low culture films invert 'traditional power hierarchies' (200), yet the effect of her discussion throughout the book is to emphasize the shared resistance to middle-class taste by both the upper-class proponents of high art and the lower-class proponents of low art. This does not so much demonstrate that trash/low culture films *invert* traditional hierarchies as it shows that both upper- and lower-class tastes are opposed to middle-class conventionality. It would be interesting to see Hawkins spend more time arguing for the distinctive value of trash/low culture cinema on the basis of its own merits, exploring how an emphasis on 'affect' over 'intellect' contributes to the unique aesthetic appeal of the body genre. Hawkins, instead, seems more concerned with intellectualizing 'trash cinema' by transforming it into something not 'trashy' at all.

Lastly, I'm left somewhat perplexed concerning the relationships that hold between the various conceptual categories Hawkins utilizes throughout the course of her discussion. Clearly, the main point Hawkins repeatedly emphasizes is that the separation between the categories of high and low culture is not unambiguous or indisputable. What is less explicit is how she intends many of the other

concepts she introduces to relate to one another. Hawkins often speaks equivocally of 'body genre', 'low culture', 'trash culture', and 'paracinema', blurring the distinctions between these categories in the same manner that she blurs the distinctions between high and low culture. The effect is sometimes confusing and leaves me wishing either for more conceptual clarification or for the elimination of some of the superfluous concepts.

Aside from these criticisms, I found _Cutting Edge_ to be an entertaining and exciting book. Hawkins gives serious attention to films that are usually ignored or denigrated by the mainstream, not necessarily because they are lacking in aesthetic worth, but because they challenge conventional assumptions about good taste.

Corning Community College, New York, USA

Copyright _Film-Philosophy_ 2002

John Marmysz, 'The Cutting Edge Between Trash Cinema and High Art', _Film-Philosophy_, vol. 6 no. 8, April 2002 <http://www.film-philosophy.com/vol6-2002/n8marmysz>.

Save as Plain Text Document...Print...Read...Recycle

Join the Film-Philosophy salon, and receive the journal articles via email as they are published. here

Film-Philosophy (ISSN 1466-4615)

PO Box 26161, London SW8 4WD, England Contact: editor@film-philosophy.com

Back to the Film-Philosophy homepage

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Web Will Kill Them All: New Media, Digital Utopia, and Political Struggle in The Italian 5-Star MovementDokument27 SeitenThe Web Will Kill Them All: New Media, Digital Utopia, and Political Struggle in The Italian 5-Star MovementAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Semantic Similarity EnsembleDokument17 SeitenThe Semantic Similarity EnsembleAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- RecoMap - An Interactive and Adaptive Map-Based RecommenderDokument5 SeitenRecoMap - An Interactive and Adaptive Map-Based RecommenderAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semantically Enriching VGI in Support of Implicit Feedback AnalysisDokument16 SeitenSemantically Enriching VGI in Support of Implicit Feedback AnalysisAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Collaborative Filtering - A Group Profiling Algorithm For Personalisation in A Spatial Recommender SystemDokument7 SeitenCollaborative Filtering - A Group Profiling Algorithm For Personalisation in A Spatial Recommender SystemAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Open-Source Web Architecture For Adaptive LbsDokument6 SeitenOpen-Source Web Architecture For Adaptive LbsAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparison of Open Source Geospatial TechnologiesDokument21 SeitenA Comparison of Open Source Geospatial TechnologiesAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 - The Similarity Jury - Combining Expert Judgements On Geographic Concepts - Ballatore Et AlDokument10 Seiten2012 - The Similarity Jury - Combining Expert Judgements On Geographic Concepts - Ballatore Et AlAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparison of Open Source Geospatial TechnologiesDokument21 SeitenA Comparison of Open Source Geospatial TechnologiesAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Holistic Semantic Similarity Measure For Viewports in Interactive MapsDokument16 SeitenA Holistic Semantic Similarity Measure For Viewports in Interactive MapsAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geographic Knowledge Extraction and Semantic Similarity in OpenStreetMapDokument21 SeitenGeographic Knowledge Extraction and Semantic Similarity in OpenStreetMapAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 - Grounding Linked Open Data in WordNet - The Case of The OSM Semantic Network - Ballatore Et AlDokument15 Seiten2013 - Grounding Linked Open Data in WordNet - The Case of The OSM Semantic Network - Ballatore Et AlAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Survey of Volunteered Open Geo-Knowledge Bases in The Semantic WebDokument27 SeitenA Survey of Volunteered Open Geo-Knowledge Bases in The Semantic WebAndrea BallatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Acr Ellen Digital Lesson 3Dokument5 SeitenAcr Ellen Digital Lesson 3Charles AvilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer Certificate SampleDokument1 SeiteTransfer Certificate Sampleashutosh SAKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pythagoras Theorem LessonDokument5 SeitenPythagoras Theorem Lessononek1edNoch keine Bewertungen

- Certify App Development With Swift Certification Apple CertiportDokument1 SeiteCertify App Development With Swift Certification Apple CertiportStoyan IvanovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ele 3 To 5 Math UkrainianDokument22 SeitenEle 3 To 5 Math UkrainianAhmed Saeid Mahmmoud OufNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Lees of SingaporeDokument14 SeitenThe Lees of Singaporecl100% (1)

- Lori Obendorf Resume 2017Dokument2 SeitenLori Obendorf Resume 2017api-347145295Noch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary School Records Form 3Dokument1 SeiteSecondary School Records Form 3yasmeenabelallyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2 Reflection-Strategies For Management of Multi-Grade TeachingDokument3 SeitenUnit 2 Reflection-Strategies For Management of Multi-Grade Teachingapi-550734106Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 International Tuition FeesDokument37 Seiten2018 International Tuition FeesSafi UllahKhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phonemic Awareness and PhonicsDokument19 SeitenPhonemic Awareness and PhonicsMaile Lei RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- TSLB3073 Week 3Dokument39 SeitenTSLB3073 Week 3Bryan AndrewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice 3 Assessment - TeamDokument20 SeitenPractice 3 Assessment - TeamTrang Anh Thi TrầnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approaches To Multicultural Curriculum ReformDokument4 SeitenApproaches To Multicultural Curriculum ReformFran CatladyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Childhood Care and Education Framework India - DraftDokument23 SeitenEarly Childhood Care and Education Framework India - DraftInglês The Right WayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Old Lesson Plan in EnglishDokument20 SeitenOld Lesson Plan in EnglishMhairo AkiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- AUD Information BulletinDokument20 SeitenAUD Information BulletinMota ChashmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AFHS Admission EnquiryDokument2 SeitenAFHS Admission EnquiryPassionate EducatorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food Science PHD CIP Code 11001: Left With Master's Not Enrolled Still EnrolledDokument1 SeiteFood Science PHD CIP Code 11001: Left With Master's Not Enrolled Still EnrolledJill DagreatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom Continuity Plan SolcpDokument2 SeitenClassroom Continuity Plan SolcpGina Dio Nonan100% (1)

- General Training IELTS Writing Task 1 - Greetings and Salutation - Jeffrey-IELTS BlogDokument4 SeitenGeneral Training IELTS Writing Task 1 - Greetings and Salutation - Jeffrey-IELTS Blogkunta_kNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action Research On Student and Pupil Absenteeism in Lower MainitDokument8 SeitenAction Research On Student and Pupil Absenteeism in Lower MainitChendieClaireSalaumGuladaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study On Training and DevelopmentDokument5 SeitenCase Study On Training and DevelopmentAakanksha SharanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top MBA Colleges in India - Ranking - Rating - FeesDokument3 SeitenTop MBA Colleges in India - Ranking - Rating - FeesSaniyaMirzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innocent Heroes Foundation (IHF)Dokument7 SeitenInnocent Heroes Foundation (IHF)api-25886263Noch keine Bewertungen

- List Beasiswa S3 PDFDokument1 SeiteList Beasiswa S3 PDFwhyudodisNoch keine Bewertungen

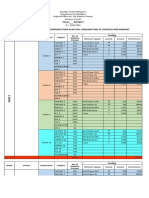

- Palo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedDokument5 SeitenPalo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedEiddik ErepmasNoch keine Bewertungen

- KS2 - 2000 - Mathematics - Test B - Part 2Dokument11 SeitenKS2 - 2000 - Mathematics - Test B - Part 2henry_g84Noch keine Bewertungen

- Foreign Language Teaching and Learning PDFDokument7 SeitenForeign Language Teaching and Learning PDFAna Laura MazieroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prospectus of Law 2019-20Dokument51 SeitenProspectus of Law 2019-20SanreetiNoch keine Bewertungen