Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

An Update On Business-iT Alignment

Hochgeladen von

joeguedesOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

An Update On Business-iT Alignment

Hochgeladen von

joeguedesCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No.

3 / Sep 2007 165 2007 University of Minnesota

Evolving IS Capabilities

An UpdAte on BUsiness-it

Alignment: A line HAs Been

drAwn

1

Jerry Luftman

Rajkumar Kempaiah

Stevens Institute of

Technology

MIS

Q

Uarterly

E

xecutive

Executive Summary

For almost three decades, practitioners, academics, consultants, and research

organizations have identifed attaining alignment between IT and business as a

pervasive problem. Is it as diffcult as drawing a line in the sand? Although we have

seen improvement, there are reasons why alignment is a persistent issueas will be

discussed.

Our research has found that no alignment silver bullet exists. Rather, alignment

involves interrelated capabilities that can be gauged by measuring six components:

communications, value, governance, partnership, scope and architecture, and skills.

These six components can then be placed in a fve-level maturity model, where Level 5 is

the highest maturity. From measuring these six components in 197 mainly Global 1,000

organizations in the United States, Latin America, Europe, and India, we found that most

organizations today are at Level 3.

Our research, and others research, has also found positive correlations between the

maturity of IT-business alignment and (1) ITs organizational structure, (2) the CIOs

reporting structure and (3) frm performance. Federated IT structures are associated

with higher alignment maturity than centralized or decentralized structures. Companies

with CIOs reporting directly to the CEO, president, or chairman have signifcantly

higher alignment maturity than those where the CIO reports to a business unit executive,

the COO, or the CFO. And higher alignment maturity correlates with higher frm

performance.

2

The PersisTenT issue of Achieving iT-Business

AlignmenT

The issue of achieving IT-business alignment was frst documented in the late 1970s

3

and was in the Top-10 IT management issues from 1980 through 1994, as reported by

the Society for Information Management (SIM). Since 1994, it has been issue #1 or

#2. These results are consistent with other studies, such as CSCs survey rankings and

The Conference Boards surveys of CEOs.

4

We have found three primary reasons why attaining IT-business alignment has been so

elusive.

1 Christina Soh and Carol Brown are the accepting Senior Editors for this article.

2 The authors wish to thank Elby Nash, currently an Affliate Professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, and

John Dorociak, who recently completed his Ph.D. under Professor Luftman in organizational management with a

specialization in information technology, for their assistance in this work.

3 The IT-business alignment issue was frst raised by Ephraim McLean and John Soden in Strategic Planning

for MIS, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1977.

4 See the 14th annual survey of Critical Issues of Information Management (North America)-CSC 2001 and:

Earl, M. J. Corporate Information Systems Management, Richard D. Irwin, Inc. Homewood, Illinois, 1983;

Ball, L., and Harris, R. SIM Members: A Membership Analysis, MIS Quarterly (6:1), March 1982, pp. 19-

38; Dickson, G. W., Leitheiser, R. L., Wetherbe, J. C., and Nechis, M. Key Information Systems Issues for the

1980s, MIS Quarterly (8:3), September 1984, pp. 135-159; Brancheau, J. C., and Wetherbe, J. C. Key Issues

in Information Systems Management, MIS Quarterly (11:1), March 1987, pp. 23-45; Brancheau, J. C., Janz, B.

D., and Wetherbe, J. C. Key Issues in Information Systems Management: 1994-95 SIM Delphi Results, MIS

Quarterly (20:2), June 1996, pp. 225-242.

MISQE is

sponsored by:

166 MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 2007 University of Minnesota

Luftman & Kempaiah / Evolving IS Capabilities

The frst reason is that the defnition of alignment

is frequently focused only on how IT is aligned

(e.g., converged, in harmony, integrated, linked,

synchronized) with the business. Alignment must also

address how the business is aligned with IT. Alignment

must focus on how IT and the business are aligned

with each other; IT can both enable and drive business

change.

The second reason is that organizations have often

looked for a silver bullet. Originally, some thought

the right technology (e.g., infrastructure, applications)

was the answer. While important, it is not enough.

Likewise, improved communications between IT

and the business help but are not enough. Similarly,

establishing a partnership is not enough nor are

balanced metrics that combine appropriate business

and technical measurements. Clearly, mature

alignment cannot be attained without effective and

effcient execution and demonstration of value, but

this alone is insuffcient.

More recently, governance has been touted as the

answerto identify and prioritize projects, resources,

and risks. Today, we also recognize the importance of

having the appropriate skills to execute and support

the environment. Our research has found that all six

of these components must be addressed to improve

alignment.

The third reason IT-business alignment has been

elusive is that there has not been an effective tool to

gauge the maturity of IT-business alignmenta tool

that can provide both a descriptive assessment and

a prescriptive roadmap on how to improve. From

measuring the six components in organizations in the

United States, Latin America, Europe, and India, we

found that most organizations today are in Level 3 of a

fve-level maturity assessment model.

Our research suggests that while there is no silver

bullet for achieving alignment, progress has been made.

In fact, we believe that our research demonstrates that

a line has been drawn.

5

When organizations cross it,

they have identifed and addressed ways to enhance

IT-business alignment. The alignment maturity model

is thus both descriptive and prescriptive. CIOs can use

it to identify their organizations alignment maturity

and identify means to increase it. Yet, that line is

dynamic and continually evolving. So alignment can

always be improved.

5 Luftman, J. Competing in the Information Age: Align in the Sand,

Oxford University Press, 2003.

A STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT

MATURITY MODEL

The Strategic Alignment Maturity (SAM) model used

in this article comes from the lead authors work since

2000.

6

The model consists of six components of an

organization that can indicate IT-business alignment

maturity. An organizations score for each one is then

placed on a maturity model, which will be discussed

shortly.

Six Components of Alignment Maturity

The six components for assessing alignment maturity

are briefy explained below. The specifc criteria

measured in each are listed in Figure 1.

Communications: 1. Measures the effectiveness

of the exchange of ideas, knowledge,

and information between IT and business

organizations, enabling both to clearly

understand the companys strategies, plans,

business and IT environments, risks, priorities,

and how to achieve them.

Value: 2. Uses balanced measurements

7

to

demonstrate the contributions of information

technology and the IT organization to the

business in terms that both the business and IT

understand and accept.

Governance: 3. Defnes who has the authority to

make IT decisions and what processes IT and

business managers use at strategic, tactical, and

operational levels to set IT priorities to allocate

IT resources.

Partnership: 4. Gauges the relationship between a

business and IT organization, including ITs role

in defning the businesss strategies, the degree

of trust between the two organizations, and how

each perceives the others contribution.

Scope and Architecture: 5. Measures ITs

provision of a fexible infrastructure, its

evaluation and application of emerging

technologies, its enabling or driving business

process changes, and its delivery of valuable

6 Luftman, J. Assessing Business-IT Alignment Maturity,

Communications of the Association for Information Systems, Volume 4,

December 2000.

7 A balanced measurement includes metrics for assessing both IT

and the business. The metrics should be easy to understand, derived

jointly by IT and business stakeholders, and prescribe a clear direction

for improvement.

2007 University of Minnesota MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 167

Evolving IS Capabilities

customized solutions to internal business units

and external customers or partners.

Skills: 6. Measures human resources practices,

such as hiring, retention, training, performance

feedback, encouraging innovation and career

opportunities, and developing the skills of

individuals. It also measures the organizations

readiness for change, capability for learning,

and ability to leverage new ideas.

Five Levels of Alignment Maturity

The scores an organization achieves for these six

components of maturity are then compared to a fve-

level maturity model to denote the organizations

IT-business alignment maturity. These fve maturity

levels draw on the core concepts of the Software

Engineering Institutes Capability Maturity Metric

(CMM), but the focus here is solely on IT-business

alignment. Following are the defnitions of the fve

levels of alignment maturity, which are summarized in

Figure 2.

Level 1: Initial or ad-hoc processes. Organizations at

Level 1 generally have poor communications between

IT and the business and also a poor understanding of

the value or contribution the other provides. Their

relationships tend to be formal and rigid, and their

metrics are usually technical rather than business

oriented. Service level agreements tend to be sporadic.

IT planning or business planning is ad-hoc. And IT is

viewed as a cost center and considered a cost of doing

business. The two parties also have minimal trust and

partnership. IT projects rarely have business sponsors

or champions. The business and IT also have little to

no career crossovers. Applications focus on traditional

back-offce support, such as e-mail, accounting, and

HR, with no integration among them. Finally, Level

1 organizations do not have an aligned IT-business

strategy.

Level 2: Committed processes. Organizations at

Level 2 have begun enhancing their IT-business

relationship. Alignment tends to focus on functions

or departments (e.g., fnance, R&D, manufacturing,

marketing) or geographical locations (e.g., U.S.,

Europe, Asia). The business and IT have limited

understanding of each others responsibilities and

roles. IT metrics and service levels are technical and

cost-oriented, and they are not linked to business

metrics. Few continuous improvement programs exist.

Management interactions between IT and the business

tend to be transaction-based rather than partnership-

based, and IT spending relates to basic operations.

Business sponsorship of IT projects is limited. At the

function level, there is some career crossover between

the business and IT. IT management considers

technical skills the most important for IT.

Level 3: Established, focused processes. In

Level 3 organizations, IT assets become more

integrated enterprise-wide. Senior and mid-level

IT management understand the business, and the

businesss understanding of IT is emerging. Service

level agreements (SLAs) begin to emerge across

Figure 1: IT-Business Alignment Maturity Criteria

-

-

- Inter -

-

iT-Business AlignmenT mATuriTy criTeriA

PArTnershiP

Business Perception of IT Value

Role of IT in Strategic Business

Planning

Shared Goals, Risk,

Rewards/Penalties

IT Program Management

Relationship/Trust Style

Business Sponsor/Champion

scoPe and

ArchiTecTure

Traditional, Enabler/Driver,

External

Standards Articulation

Architectural Integration

- Functional Organization

-Enterprise

-Inter-enterprise

Architectural Transparency,

Agility, Flexibility

Manage Emerging Technology

sKills

by Business

Liaison Effectiveness

communicATions

Understanding of Business

by IT

Understanding of IT

Inter/Intra-organizational

Learning/Education

Protocol Rigidity

Knowledge Sharing

vAlue

IT Metrics

Business Metrics

Balanced Metrics

Service Level Agreements

Benchmarking

Formal Assessments/Reviews

Continuous Improvement

governAnce

Organization Structure

IT Investment Management

Prioritization Process

Business Strategic Planning

IT Strategic Planning

Budgetary Control

Steering Committee(s)

Cultural Locus of Power

Change Readiness

Innovation, Entrepreneurship

Management Style

Career Crossover; Training/Education

Hiring and Retaining

Interpersonal Environment

Social, Political, Trusting

168 MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 2007 University of Minnesota

Luftman & Kempaiah / Evolving IS Capabilities

the enterprise; although the results are not always

shared or acted upon. Strategic planning tends to be

done at the business unit level, although some inter-

organizational planning has begun. IT is increasingly

viewed by the business as an asset, but project

prioritization still usually responds to the loudest

voice. Formal IT steering committees emerge and

meet regularly. IT spending tends to be controlled

by budgets, and IT is still seen as a cost center. But

awareness of ITs investment potential is emerging.

The business is more tolerant of risk and is willing

to share some risk with IT. At the function level, the

business sponsors IT projects and career crossovers

between business and IT occur. Both business and

technical skills are important to business and IT

managers. Technology standards and architecture

have emerged at both the enterprise level and with key

external partners.

Level 4: Improved, managed processes.

Organizations at Level 4 manage the processes they

need for strategic alignment within the enterprise.

One of the important attributes of this level is that the

gap has closed between IT understanding the business

and the business understanding IT. As a result, Level

4 organizations have effective decision making and

IT provides services that reinforce the concept of IT

as a value center. Level 4 organizations leverage their

IT assets enterprise-wide, and they focus applications

on enhancing business processes for sustainable

competitive advantage. SLAs are also enterprise-wide,

and benchmarking is a routine practice. Strategic

business and IT planning processes are managed

across the enterprise. Formal IT steering committees

meet regularly and are effective at the strategic,

tactical, and operational levels. The business views

IT as a valued service provider and as an enabler (or

driver) of change. In fact, the business shares risks and

rewards with IT by providing effective sponsorship

and championing all IT projects. Overall, change

management is highly effective. Career crossovers

between business and IT occur across functions,

with business and technical skills recognized as very

important to the business and IT.

Level 5: Optimized processes. Organizations

at Level 5 have optimized strategic IT-business

alignment through rigorous governance processes that

integrate strategic business planning and IT planning.

Alignment goes beyond the enterprise by leveraging

IT with the companys business partners, customers,

and clients, as well. IT has extended its reach to

encompass the value chains of external customers and

suppliers. Relationships between the business and IT

are informal, and knowledge is shared with external

partners. Business metrics, IT metrics, and SLAs

also extend to external partners, and benchmarking

is routinely performed with these partners. Strategic

Figure 2: Strategic Alignment Maturity Summary

2007 University of Minnesota MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 169

Evolving IS Capabilities

F

i

g

u

r

e

3

:

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

M

a

t

u

r

i

t

y

L

e

v

e

l

s

b

y

t

h

e

S

i

x

C

r

i

t

e

r

i

a

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

N

a

m

e

#

o

f

C

o

m

p

a

n

i

e

s

C

o

m

m

u

n

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

C

o

m

p

e

t

e

n

c

y

G

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

P

a

r

t

n

e

r

s

h

i

p

S

c

o

p

e

o

f

I

T

A

r

c

h

i

t

e

c

t

u

r

e

S

k

i

l

l

s

O

V

E

R

A

L

L

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

R

e

t

a

i

l

7

3

.

6

5

3

.

5

7

3

.

5

2

3

.

9

3

.

8

1

3

.

5

1

3

.

7

T

r

a

n

s

p

o

r

t

a

t

i

o

n

3

3

.

1

3

.

8

3

.

5

7

3

.

5

3

3

.

6

3

3

.

6

3

.

5

4

H

o

t

e

l

/

E

n

t

e

r

t

a

i

n

m

e

n

t

6

3

.

4

6

3

.

4

6

3

.

5

3

3

.

4

4

3

.

6

2

3

.

4

5

3

.

4

9

S

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

2

7

3

.

1

8

3

.

2

1

3

.

2

8

3

.

3

2

3

.

2

8

3

.

2

2

3

.

2

I

n

s

u

r

a

n

c

e

6

3

.

1

6

3

.

1

5

3

.

3

3

.

1

7

3

.

2

4

2

.

9

3

.

1

5

M

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

4

6

3

.

2

2

3

.

1

3

.

1

5

3

.

3

3

.

1

7

2

.

9

3

.

1

5

H

e

a

l

t

h

5

3

.

0

6

2

.

7

9

3

.

3

4

3

.

0

6

3

.

2

4

3

.

1

7

3

.

1

1

C

h

e

m

i

c

a

l

7

2

.

7

8

2

.

8

4

2

.

9

3

2

.

8

7

3

.

2

8

2

.

8

4

2

.

9

3

F

i

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

5

7

2

.

8

3

2

.

9

2

2

.

9

8

2

.

8

6

3

.

0

3

2

.

7

2

.

9

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

6

2

.

9

4

2

.

7

3

.

0

7

3

.

0

7

2

.

9

9

2

.

6

7

2

.

9

O

i

l

/

G

a

s

/

M

i

n

i

n

g

3

2

.

9

6

2

.

8

6

2

.

9

2

2

.

8

4

3

.

2

2

2

.

6

4

2

.

9

U

t

i

l

i

t

i

e

s

7

2

.

9

6

2

.

9

4

2

.

8

1

2

.

8

4

3

.

1

3

2

.

6

2

.

8

8

P

h

a

r

m

a

c

e

u

t

i

c

a

l

1

4

2

.

7

4

2

.

5

8

2

.

7

1

2

.

6

4

2

.

8

5

2

.

7

1

2

.

7

E

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

3

1

.

8

6

1

.

7

4

1

.

6

6

1

.

4

1

1

.

7

8

1

.

8

3

3

1

.

7

1

O

v

e

r

a

l

l

A

l

i

g

n

m

e

n

t

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

S

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

0

4

170 MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 2007 University of Minnesota

Luftman & Kempaiah / Evolving IS Capabilities

business and IT planning are integrated across the

organization, as well as outside the organization.

ANALYSIS OF THE ALIGNMENT

DATA

This study involved analyzing the responses of

business and IT executives from 197 companies,

primarily Global 1,000 companies.

8

Of the 197

organizations, 124 were based in the United States,

38 were in Latin America (the largest in the region,

although below the Global 1,000 level), 11 were

in Europe, and 24 were in India (half were in the IT

services industry). This article only discusses the

companies at Levels 2, 3, and 4, which comprise about

96% of the participants. We found Level 5 companies

in an earlier pilot.

Four Main Observations

We analyzed the responses in numerous ways.

9

Our

analyses uncovered four main observations, which are

briefy presented below, along with an accompanying

fgure for each one.

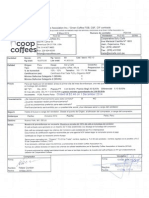

Industries vary in their alignment maturity. One

analysis was by industry. As can be seen in Figure 3,

the average overall maturity score for all the companies

was 3.04shown by the midpoint dark line. The three

industries with the highest maturity scoresretail,

transportation and hotel/entertainmentwere well

above the midpoint for Level 3 companies; however,

these industry samples were quite small.

Alignment maturity is rising. A second analysis

compared maturity scores across years. As can be

seen in Figure 4, the frst set of data was collected

from 2000 to 2003. The average alignment maturity

was a high Level 2 (2.99). The second set of data was

collected from 2004 to 2007. The average maturity

8 The six components of alignment maturity were initially validated

by evaluating 25 Fortune 500 companies. Early studies included fve

companies that were invited to participate because of their exemplar

reputation; these companies were assessed at Level 5. Our procedure

for assessing maturity is described in the Appendix. Some two-thirds

of the data was gathered from interviews or group discussions. The rest

came from questionnaires.

9 The fndings for subsets of participants have been reported in

Luftman, op. cit., 2003, as well as Nash, E. Assessing IT As a Driver

or Enabler of Transformation in the Pharmaceutical Industry Employing

the Strategic Alignment Maturity Model, Doctoral Dissertation,

Stevens Institute of Technology, 2005; Sledgianowski, D., Luftman,

J., and Reilly, R. Identifcation of Factors Affecting the Maturity

of IT-Business Strategic Alignment, Proceedings of the Americas

Conference on Information Systems, August 2004; Sledgianowski, D.

Identifcation of IT-Business Strategic Alignment Maturity Factors,

Doctoral Dissertation, Stevens Institute of Technology, 2005.

was a low Level 3 (3.18). This rise demonstrates that

maturity did increase.

The fgure also shows that some 96% of the 197

organizations were either at Level 2, Level 3, or Level

4 during these timeframes11.68% were at Level 2,

63.96% at Level 3, and 20.3% at Level 4. In the 2000-

2003 data, about 75% of the U.S. companies were at

Level 3 or higher. In 2004-2007, about 94% of the

U.S. companies were Level 3 or above. Obviously,

a marked improvement took place; a line has been

drawn.

Business executives score alignment higher than

IT executives. A fourth comparison was between

IT and business respondents, at the granular level

of the individual criteria within the six components

of maturity. In all, we had 1,527 respondents, with

727 from IT (105 CIOs, 10 CTOs, and 612 other IT

executives) and 800 from the business (88 CEOs, 97

CFOs, 159 VPs, and 456 other business executives).

Figure 5 notes that their average alignment score

overall was 3.04. It also illustrates that the business

executives generally ranked alignment maturity higher

than the IT executives.

This overall score of 3.04 indicates that IT is

becoming embedded with the business. Interestingly,

Scope and Architecture scored the highest of the six

(average maturity 3.14), while Skills scored the lowest

(2.90). Those criteria with the lowest combined IT and

business scores are highlighted in the fgure.

Rankings among Level 2, 3, and 4 companies are

remarkably consistent. A ffth analysis compared the

maturity scores of the companies in Levels 2, 3, and 4.

As shown in Figure 6, the rankings are very consistent.

Respondents in the Level 4 companies ranked almost

every criterion in the Level 4 rangeas you would

expectand only one criterion was rated lower by

Level 3 respondents than Level 2 respondentsagain,

as you would expect. Furthermore, overall, the three

sets of lines mirror each other.

Similarities and Differences Among the

Criteria

Figure 6, with the comparisons among the Level 2, 3,

and 4 organizations, deserves more analysis. So we

now look at their differences and similarities.

Scope and Architecture: Scope and Architecture

received the highest overall score of 3.14 among the

six components. This fnding reveals that the typical

frm in this sample is well within Level 3 in this

maturity component. Scope and Architecture is the

2007 University of Minnesota MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 171

Evolving IS Capabilities

Figure 4: Maturity Levels by Years

Years Number of

Companies

% of

companies

in level 1

1

% of

companies

in level 2

2

% of

companies

in level 3

3

% of

companies

in level 4

4

% of

companies

in level 5

5

Overall

Average

2000-2003 83 2.41 20.48 46.99 24.10 6.02 2.99

2004-2007 114 0.88 5.26 76.32 17.54 0.00 3.18

Overall 197 1.52 11.68 63.96 20.30 2.54 3.04

Level 1: organizations with maturity average in the range of 1.0-1.99 1.

Level 2: organizations with maturity average in the range of 2.0-2.99 2.

Level 3: organizations with maturity average in the range of 3.0-3.59 3.

Level 4: organizations with maturity average in the range of 3.60-4.50 4.

The level 5 companies with maturity average > 4.50 were selected as part of a pilot group benchmarked 5.

because of their exemplar reputation; the overall 2000-2003 average would only be 2.90 if these 5

companies were excluded

only technical component in the model. It indicates

how well IT provides a fexible infrastructure,

introduces emerging technologies, fosters business

process change, and delivers value to the business,

customers, and partners. As business executives

recognize the importance of integration across

their enterprise and external partners, they realize

the importance of understanding how to leverage

information technologies to carry out their business

strategies. Figure 6 provides an interesting comparison

among the responses from Level 2, 3, and 4 companies

in Architectural Flexibility (one of the fve criteria in

Scope and Architecture). Level 2 and 3 respondents

gave it the lowest score in Scope and Architecture. But

those from Level 4 did not, which suggests that Level

4 companies place more importance on Architectural

Flexibility. The rationale for this difference is

probably that Level 2 and 3 organizations tend to

view IT infrastructure as a utility that provides basic

IT services at minimum cost. Level 4 organizations,

on the other hand, view their IT infrastructure as a

resource to enable fast response to changes in the

marketplace. Standards Articulation and Compliance

provides another contrast across the maturity levels.

Level 2 organizations defne and enforce standards

at the function level, whereas Level 4 organizations

defne and enforce them across business units, because

they recognize the importance of integrating across the

frm. In fact, many Level 4s are beginning to integrate

their standards with external business partners. With

Level 4 architecture, business or IT change can be

made transparently across the organization, as the

following example illustrates. One online retailer in

this study, with a Level 4.0 maturity, has a customer

base of 60 million and more than one million external

partners. It has driven its technology scope and IT

architecture based on its customers expectations. Its

IT architecture is based around Web services, which

permit its transaction layer systems to handle online

business applications, while shielding its partners

databases from having to change. The difference

between a Level 4 and Level 5 company is how much

an enterprise has expanded its IT impact externally

to its customers and partners. This company has

the earmarks of approaching Level 5 architecture

maturity.

Governance: Governance received an overall maturity

score of 3.10, as shown in Figure 6, as did Partnership.

These two components of alignment maturity tied

for the second highest maturity score. IT Governance

measures how much IT decision-making authority is

defned and shared among organizational units and

how much both IT and business managers participate

in setting priorities for allocating IT resources.

Governance also involves managing external partners

and ensuring regulatory compliance. Governance is not

just about specifc decisions. It is about the underlying

principleswho makes the decisions, why, and how.

Governance maturity increases as the processes for

integrating business and IT priorities, planning, and

budgeting become more effcient and effective.

For effective IT governance, companies also need

effective communications, partnerships, and value

metrics between IT and the business. The overall

score of 3.10 places the typical frm in this sample

at Level 3 governance maturity. All three levels of

organizations scored Budgetary Control lowest in

this Governance component. Even though budgetary

control is considered the most basic governance

mechanism, it tends to promote the perception of IT

as a cost rather than as an investment or a generator

172 MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 2007 University of Minnesota

Luftman & Kempaiah / Evolving IS Capabilities

F

i

g

u

r

e

5

:

C

o

m

p

a

r

i

s

o

n

s

o

f

B

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

a

n

d

I

T

E

x

e

c

u

t

i

v

e

s

R

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

2

.

5

0

2

.

7

0

2

.

9

0

3

.

1

0

3

.

3

0

3

.

5

0

3

.

7

0

3

.

9

0

u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f B u s i n e s s b y i T

i n t e r / i n t r a o r g a n i z a t i o n a l l e a r n i n g

K n o w l e d g e s h a r i n g

B u s i n e s s m e t r i c s

s e r v i c e l e v e l a g r e e m e n t s

f o r m a l l y a c c e s s i T i n v e s t m e n t

c o n t r i b u t i o n t o i T f u n c t i o n

b u s i n e s s s t r a t e g i c p l a n n i n g

B u d g e t a r y c o n t r o l

i T i n v e s t m e n t m a n a g e m e n t

P r i r i t i z a t i o n P r o c e s s

b u s i n e s s p e r c e p t i o n o f i T v a l u e

s h a r e d r i s k s a n d r e w a r d s

r e l a t i o n s h i p / t r u s t s t y l e

e x t e r n a l s t a n d a r d s A r t i c u l a t i o n

B u s i n e s s a n d i T c h a n g e s

l o c u s o f P o w e r

c a r e e r c r o s s o v e r o p p r t u n i t i e s

s o c i a l , P o l i t i c a l , T r u s t i n g i n t e r p e r s o n a l

B

u

s

i

T

A

v

g

o

v

e

r

a

l

l

A

l

i

g

n

m

e

n

t

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

0

4

g

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

1

0

P

a

r

t

n

e

r

s

h

i

p

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

1

0

s

c

o

p

e

&

A

r

c

h

i

t

e

c

t

u

r

e

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

1

4

s

k

i

l

l

s

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

2

.

9

0

c

o

m

m

u

n

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

0

3

v

a

l

u

e

m

e

t

r

i

c

s

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

2

.

9

9

1

.

2

.

2

.

5

.

4

.

6

.

l

o

w

e

s

t

R e a c t / R e s p o n d Q u i c k l y

I n t e r / I n t r a - o r g a n i z a t i o n a l l e a r n i n g

U n d e r s t a n d i n g o f B u s i n e s s b y I T

P r o t o c o l r i g i d i t y

K n o w l e d g e S h a r i n g

u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f i T b y B u s i n e s s

L i a i s o n s B r e a d t h / E f f e c t i v e n e s s

R o l e o f I T i n S t r a t e g i c B u s i n e s s P l a n n i n g

S h a r e d G o a l s , R i s k , R e w a r d s / P e n a l t i e s

B u s i n e s s P e r c e p t i o n o f i T v a l u e

I T P r o g r a m M a n a g e m e n t

R e l a t i o n s h i p / T r u s t S t y l e

B u s i n e s s S p o n s o r / C h a m p i o n

B u s i n e s s S t r a t e g i c P l a n n i n g

I T S t r a t e g i c P l a n n i n g

B u d g e t a r y c o n t r o l

I T I n v e s t m e n t M a n a g e m e n t

S t e e r i n g C o m m i t t e e s

P r i o r i t i z a t i o n P r o c e s s

I n n o v a t i o n , E n t r e p r e n e u r s h i p

L o c u s o f P o w e r

c a r e e r c r o s s o v e r

e d u c a t i o n , c r o s s - T r a i n i n g

S o c i a l , P o l i t i c a l , T r u s t i n g I n t e r p e r s o n a l

A t t r a c t a n d R e t a i n B e s t T a l e n t

C h a n g e R e a d i n e s s

I T M e t r i c s

B u s i n e s s M e t r i c s

B a l a n c e d m e t r i c s

s e r v i c e l e v e l A g r e e m e n t s

B e n c h m a r k i n g

F o r m a l A s s e s s m e n t s / R e v i e w s

C o n t i n u o u s I m p r o v e m e n t

d e m o n s t r a t e d c o n t r i b u t i o n o f i T t o B u s i n e s s

S c o p e o f I T S y s t e m s

A r c h i t e c t u r a l I n t e g r a t i o n

B u s i n e s s a n d I T C h a n g e M a n a g e m e n t

i n f r a s t r u c t u r e f l e x i b i l i t y

S t a n d a r d s A r t i c u l a t i o n & C o m p l i a n c e

2007 University of Minnesota MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 173

Evolving IS Capabilities

F

i

g

u

r

e

6

:

C

o

m

p

a

r

i

s

o

n

s

o

f

L

e

v

e

l

2

,

3

,

a

n

d

4

R

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

1

.

5

0

2

.

0

0

2

.

5

0

3

.

0

0

3

.

5

0

4

.

0

0

4

.

5

0

u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f B u s i n e s s b y i T

i n t e r / i n t r a o r g a n i z a t i o n a l l e a r n i n g

K n o w l e d g e s h a r i n g

B u s i n e s s m e t r i c s

s e r v i c e l e v e l a g r e e m e n t s

f o r m a l l y a c c e s s i T i n v e s t m e n t

c o n t r i b u t i o n t o i T f u n c t i o n

b u s i n e s s s t r a t e g i c p l a n n i n g

B u d g e t a r y c o n t r o l

i T i n v e s t m e n t m a n a g e m e n t

P r i r i t i z a t i o n P r o c e s s

r o l e o f i T i n s t r a t e g i c b u s i n e s s p l a n n i n g

i T P r o g r a m m a n a g e m e n t

b u s i n e s s s p o n s a r s / c h a m p i o n s

T r a d i t i o n a l e n a b l e r / d r i v e r

a r c h i t e c t u r e i n t e g r a t i o n

A r c h i t e c t u r a l T r a n s p a r e n c y , f l e x i b i l i t y

i n n o v a t e , e n t e r p r e n e u r i a l e n v i r o r n m e n t

c h a n g e r e a d i n e s s

e d u c a t i o n , c r o s s T r a i n i n g

A t t r a c t a n d r e t a i n B e s t T a l e n t

s

c

o

p

e

a

n

d

A

r

c

h

i

t

e

c

t

u

r

e

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

1

4

1

.

i

T

g

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

1

0

2

P

a

r

t

n

e

r

s

h

i

p

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

1

0

2

.

i

T

v

a

l

u

e

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

2

.

9

9

5

.

c

o

m

m

u

n

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

3

.

0

3

4

.

s

k

i

l

l

s

A

v

g

.

s

c

o

r

e

:

2

.

9

0

6

.

l

e

v

e

l

4

l

e

v

e

l

3

l

e

v

e

l

2

h

-

h

i

g

h

l

-

l

o

w

I n t e r / I n t r a - o r g a n i z a t i o n a l L e a r n i n g

U n d e r s t a n d i n g o f B u s i n e s s b y I T

P r o t o c o l r i g i d i t y

K n o w l e d g e S h a r i n g

u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f i T b y B u s i n e s s

L i a i s o n s B r e a d t h / E f f e c t i v e n e s s

r o l e o f i T i n s t r a t e g i c B u s i n e s s P l a n n i n g

S h a r e d G o a l s , R i s k , R e w a r d s / P e n a l t i e s

B u s i n e s s P e r c e p t i o n o f i T v a l u e

I T P r o g r a m M a n a g e m e n t

R e l a t i o n s h i p / T r u s t S t y l e

B u s i n e s s s p o n s o r / c h a m p i o n

B u s i n e s s S t r a t e g i c P l a n n i n g

I T S t r a t e g i c P l a n n i n g

B u d g e t a r y c o n t r o l

I T I n v e s t m e n t M a n a g e m e n t

S t e e r i n g C o m m i t t e e s

P r i o r i t i z a t i o n P r o c e s s

I n n o v a t i o n , E n t r e p r e n e u r s h i p

L o c u s o f P o w e r

c a r e e r c r o s s o v e r

e d u c a t i o n , c r o s s - T r a i n i n g

S o c i a l , P o l i t i c a l , T r u s t i n g I n t e r p e r s o n a l

A t t r a c t a n d R e t a i n B e s t T a l e n t

c h a n g e r e a d i n e s s

I T M e t r i c s

B u s i n e s s M e t r i c s

B a l a n c e d m e t r i c s

s e r v i c e l e v e l A g r e e m e n t s

B e n c h m a r k i n g

F o r m a l A s s e s s m e n t s / R e v i e w s

C o n t i n u o u s I m p r o v e m e n t

S c o p e o f I T S y s t e m s

A r c h i t e c t u r a l I n t e g r a t i o n

B u s i n e s s a n d I T C h a n g e M a n a g e m e n t

i n f r a s t r u c t u r e f l e x i b i l i t y

s t a n d a r d s A r t i c u l a t i o n & c o m p l i a n c e

h

h

h

l

h

h

h

l

l

l

l

l l

h

h

h

h

h

l

l

l

l

l

h

l

h

l

h

h

l

l

l

l

h

h

h

l

l

r e a c t / r e s p o n d Q u i c k l y

d e m o n s t r a t e d c o n t r i b u t i o n o f i T t o B u s i n e s s

174 MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 2007 University of Minnesota

Luftman & Kempaiah / Evolving IS Capabilities

of proft. Perhaps that is why all levels rated this

maturity low.All three levels also gave their highest

Governance rating to React/Respond Quickly,

which indicates that IT recognizes the importance

of being fexible with its business partners. As

could be expected, the Level 4 frms rated this item

considerably higher than Levels 2 and 3. We found

that Business Strategic Planning with IT participation

and IT Strategic Planning with business participation

tended to occur only at the functional level, with

some IT participation. For example, one large fnance

company (3.0 maturity level) employs over 300,000

people and has revenues of more than $1 billion every

11 days. It has a federated IT governance structure (an

important governance consideration) with separation

of powers. Its executive branch is executive

management and its board of directors, which

oversee strategic aspects as well as development and

design priorities. Its legislative branch establishes

the goals and directions of its service oriented

architecture (SOA) efforts. And its judicial branch

is comprised of enterprise architectural boards, which

deal with confict resolution and compliance audits.

SOA initiatives are also divided hierarchically, with

enterprise, division, line of business, and departmental

levels. Management believes that mature alignment

requires effective steering committees that address

strategic, tactical, and operational decisions.

Partnership: Partnership is the relationship between

the business and IT and includes ITs role in defning

business strategies, the degree of trust between the

parties, and each ones perception of the others

contribution. Mutual trust and sharing of risks and

rewards are key attributes. The overall score of 3.10

reveals that the typical frm in this sample has a

Level 3 Partnership maturity, where IT does play a

role in defning business strategies. All three levels

of frms in this sample scored Business Sponsor/

Champion as the highest Partnership item, which

suggests that business sponsorship of initiatives is

critical to partnering. Level 2 organizations generally

only have a senior IT sponsor/champion for IT-based

initiatives. Level 3 organizations often have a senior

IT and business sponsor/champion at a functional unit

level. Level 4 organizations often have a senior IT

and business sponsor/champion at the corporate level.

Business executives must be visible in their roles as

project sponsor and champion because only they, not

IT executives, can require the business to make the

appropriate changes to the business for an IT project to

deliver its full value. For example, a large electronics

manufacturer with an overall maturity level of 3.13

successfully implemented a global supply chain

management system. Its success stemmed from the

senior business partners making sure that the business

actually implemented the appropriate organizational

and business process changes in concert with the

IT changes. These changes extended beyond the

company to foreign suppliers, integrating them into

the companys design, build, and distribution of its

products. Without the visible and active involvement

of the business sponsor and champions, this project

would have failed.

Communications: Communications captures

how well IT and business executives understand

each other. The overall score of 3.03 in this study

places Communications in fourth place among the

components and at a Level 3 maturity.

As Figure 6 shows, Liaisons Breadth/Effectiveness

is ranked highest by all three levels of organizations.

Interestingly, at one large Level 3 insurance company,

communications between the IT and business

organizations became so effective that management

decided the liaisons were no longer necessary.

Unfortunately, this is rare. Too frequently, liaisons

serve mainly as translatorsbuffers between IT and

the businessrather than as facilitators who enhance

the IT-business relationship.

As also shown in Figure 6, Level 2 frms rank Inter/

Intra-Organizational Learning lowest, likely because

it generally takes place via traditional newsletters,

reports, and group e-mails. In addition, both Level

2 and Level 3 organizations gave Protocol Rigidity

(which means diffculty in accessing stakeholders)

their highest score. In general, the communication

style between the business and IT at Level 2 tends to

be one-way, from the business. At Level 3, it tends to

be two-way. Apparently, the respondents were satisfed

with these styles, hence the high scores. Importantly,

Level 3 and Level 4 organizations gave Understanding

of IT by Business the lowest Communications score.

While it is important for both IT to understand the

business and the business to understand IT, clearly,

respondents believe that business understanding of

IT is a larger concern than ITs understanding of the

business. IT and business need to work together to

identify opportunities for enhancing effective and

effcient communications among the organizations.

As an example, another large insurance company with

a Level 3.3 maturity realized that its IT staff members

frst needed to understand the businesss processes

before they could identify opportunities to leverage

IT in those processes. So IT staff are continually

given opportunities to work closely with senior

business managers, as well as take courses that focus

2007 University of Minnesota MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 175

Evolving IS Capabilities

on the insurance industry and the business processes

important to the frms future success.

Value: Value is the contribution that IT and the IT

organization make to the business in terms that the

business and IT understand and accept. To demonstrate

their business value, many IT organizations need

a balanced dashboard that demonstrates ITs

contribution to the business.

As illustrated in Figure 6, all three levels of

respondents rated Demonstrated Contribution of IT

to the Business the highest in the Value component.

Yet, Value ranks ffth of the six components, garnering

only a 2.99 overall. So the rank within Value is high,

but not overall. Even so, this high ranking illustrates

that both the business and IT at all levels recognize

the importance of measuring the contribution that

individual IT initiatives make on the business.

Interestingly, Level 2s rating of Demonstrated

Contribution of IT to the Business is actually

higher than Level 3s ratingwhich is unexpected.

Perhaps this result is due to Level 3 frms focus on

benchmarking and formal reviews, which they may

see as obviating the need to measure IT contribution.

Level 4 organizations rank Demonstrated Contribution

of IT to the Business as the most mature of all

the criteria. A large trucking company, with an

alignment maturity of 4.4, demonstrates why. It has

leveraged its internal value metrics to change the

face of competition. Originally, its metrics aimed to

encourage more effcient and competitive IT-enabled

processes, because its transportation industry faced

falling demand and highly competitive pricing. Its

metrics led the trucking company to enhance customer

service. Customers can dial directly into the company

and review the status and location of any delivery.

Satellite technology lets the company pinpoint truck

location. The company collects this data not only for

its customers but to improve its business processes.

This data is continually analyzed. If we can measure

it, we can manage it refects the companys success in

IT-business alignment.

On the other hand, Level 3 and 4 organizations

gave SLAs the lowest score in the Value category.

Perhaps their rating is low because they see SLAs

as only setting the baselines for IT delivery, not

for contributing to business success. SLAs defne

expectations for IT support. To create proper SLAs,

and effective management processes around them, the

business needs to understand IT processes. Level 2

SLAs are primarily technically oriented. Level 3 SLAs

are both technically and relationship oriented. They

are at the functional level and are emerging at the

enterprise level. Level 4 SLAs mature beyond Level 3

at the enterprise level.

Skills: Skills is the human resources practices in IT

such as training, performance feedback, encouraging

innovation, and providing career opportunitiesas

well as the IT organizations readiness for change,

capability for learning, and ability to leverage new

ideas. Skills received the lowest overall score (2.90) of

the six components, which reveals that the typical frm

is at a Level 2 in this aspect of IT-business alignment

maturity. With the low scores for Attract and Retain

Best Talent, it is no wonder this concern has surpassed

IT-business alignment in the 2007 SIM survey of

major issues. The Change Readiness scores are also

revealing. The high rating by the Level 4 organizations

indicates that they recognize the importance of having

an effective change management process where IT and

the business work closely together. Career Crossover

similarly shows a distinct maturity gap between the

Level 4s and the Level 2s and 3s. The Level 4s see this

criterion as an excellent vehicle for preparing business

and IT staff with the empathy and the experience

needed to build strong IT-business relations. The

Level 2s and 3s do not take advantage of this practice.

For example, a large aerospace company assessed its

Skills maturity at Level 2. It had a command-and-

control management style across IT and the business.

Power resided in siloed operating units. Diverse

business cultures abounded. To move upward in its

alignment maturity, this organization would need to

instill a non-political, trusting environment between

the business and IT. Risks would need to be shared,

and the culture would need to reward innovation

and entrepreneurship. Since completing its maturity

assessment, management realized the potential value

of addressing these issues. In the past year and a half,

it has raised itself to Level 3.2. It created a well-

defned education program, as well as implemented

rotational assignments among its operating units.

Hopefully, the level of detail of the criteria provides

CIOs and their business partners fodder for evaluating

their own alignment maturity. Our research has

also uncovered links between alignment and IT

organizational structure, and alignment and CIO

reporting structure.

Alignment and IT Organizational

Structure

Does organizational structure affect alignment

maturity? We think so. The participants in this study

reported having three IT organizational structures:

176 MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 2007 University of Minnesota

Luftman & Kempaiah / Evolving IS Capabilities

Central IT organization (40% of respondents):

All IT resources report to one unit, usually led

by a CIO.

Decentralized IT organization (13% of

respondents): Each business unit has its own IT

organization.

Federated IT organization (47% of respondents):

Some parts of IT are centralized (e.g., IT

infrastructure, standards, common systems) and

other parts are decentralized (e.g., application

resources specifc to the business units).

Previously, IT organizational structure has been

associated with strategic alignment.

10

So we looked

for differences in alignment maturity among the

three structures. We found that organizations with

a federated IT had signifcantly higher alignment

maturity (3.31) than those with centralized (2.86) or

decentralized (2.89) structures. Therefore, it appears

that IT organizations that combine the strengths of

centralization and decentralization, while minimizing

their weaknesses, enhance their IT-business

relationship. However, organizing IT federally will

not by itself ensure mature alignment because there

is no silver bullet. But the evidence suggests that IT

organization structure can enable alignment.

Alignment and the CIO Reporting

Structure

Another frequent IT governance topic of discussion

is the reporting structure of the senior IT executive

because it can affect IT-business alignment. The

participants in this study reported four CIO reporting

structures. The CIOs report to the:

CEO/President/Chairman (46% of companies),

Business Unit Executive (23% of companies),

COO (19% of companies),

CFO (12% of companies).

Our analysis found that organizations whose senior IT

executive reported to the CEO, president, or chairman

had signifcantly higher alignment maturity (3.42) than

those whose senior IT executive reported to a business

unit executive (3.23), the COO (3.02), or the CFO

(2.89). This fnding suggests that having the senior IT

executive reporting to the CEO, president, or chairman

could provide the best structure for maturing their

IT-business alignment. However, having the senior

10 See Agarwal, R., and Sambamurthy, V. Principles and Models

for Organizing the IT Function, MIS Quarterly Executive (1:1), March

2002, pp. 1-16.

IT executive reporting to the most senior business

executive will not by itself ensure mature alignment

because, again, there is no silver bullet. But the

evidence suggests that the CIO reporting structure also

enables alignment.

AlignmenT And firm

PerformAnce

Research over the past three decades has consistently

identifed IT-business alignment as a pervasive

problem. This research shows that organizations

can evolve multiple IT capabilities and management

mechanisms to better align IT and business. Although

this study focused on Global 1,000 organizations, it

can apply (and has been applied) to organizations of

all sizes.

Even more compelling a reason to address the IT-

business alignment issue is recent evidence of a link

between IT-business alignment and frm performance.

The same assessment criteria discussed here were used

in two research projectsone in pharmaceuticals

11

and the other in banking.

12

These studies found an

association between higher levels of IT-business

alignment maturity and higher levels of frm

performance. Such fndings add credence to the belief

that developing IT capabilities to achieve a higher

level of IT-business alignment maturity is important.

This study provides a roadmap for improving IT-

business harmony, through the six components

that affect maturity. Organizations can begin by

benchmarking their IT-business alignment and

then developing their own path for maturing their

alignment.

ABouT The AuThors

Jerry Luftman

Jerry Luftman (jluftman@stevens.edu) is Associate

Dean and a Distinguished Professor for the graduate

11 Based on data collected in 2004 and 2005 from 145 IT and

business executives in nine large pharmaceutical frms, Nash found

that companies with higher total sales and higher productivity generally

reported higher levels of alignment maturity. See Nash, E. Assessing

IT as a Driver or Enabler of Transformation in the Pharmaceutical

Industry Employing the Strategic Alignment Maturity Model, Doctoral

Dissertation, Stevens Institute of Technology, 2005.

12 Based on data collected in 2006 and 2007 from 27 companies

in the banking industry for an in-progress doctoral dissertation at

Stevens Institute of Technology, Dorociak has reported fnding a strong

association between higher company performance measures (market

share, use of new products, customer reputation, quality, return on

investments (ROI), and technical innovation) and higher IT-business

alignment maturity levels.

2007 University of Minnesota MIS Quarterly Executive Vol. 6 No. 3 / Sep 2007 177

Evolving IS Capabilities

information systems programs at Stevens Institute

of Technology, where he also earned his doctoral

degree in information management. His 23-year

career with IBM included strategic positions in IT

management, management consulting, information

systems, marketing, and executive education. He

played a leading role in defning and introducing

IBMs Consulting Group. As a practitioner, he has

held several positions in IT, including CIO.

Luftmans research papers have appeared in dozens

of professional journals and books. His book,

Competing in the Information Age: Align in the Sand,

was published by Oxford University Press. He has

been a presenter at many executive and professional

conferences and is regularly called on by many of

the largest companies in the world. He has served on

the SIM Executive Board for over 10 years and was

president of the New Jersey Chapter of SIM.

Rajkumar Kempaiah

Rajkumar Kempaiah (rajkumar.kempaiah@stevens.

edu) is a Ph.D. candidate in information management

at the Howe School of Technology Management,

Stevens Institute of Technology, where he currently

teaches courses in systems analysis and design and IS

management. His research interests are in IT-business

alignment, knowledge management, and analysis and

development of information systems.

APPendix: The reseArch

Process

The maturity levels for about two-thirds of the

organizations in this study were gathered from

interviews or group (evaluation team) discussions;

the data from the remaining one-third were gathered

from questionnaires. The procedure using evaluation

teams was as follows.

Each of the criteria within the six components 1.

were frst assessed individually by an evaluation

team that was typically comprised of leading IT

and business executives from the organization

being assessed. All items for each component

were rated on a 15 point Likert scale, where

1 denoted very ineffective and 5 denoted

very effective. Based on these ratings, each of

the 47 criteria (only the criteria used as maturity

vehicles are included in the fgures) and the

six components were categorized at Level

1, Level 2, Level 3, Level 4, or Level 5. The

fgures do not include the items used to measure

organization structure and IT reporting.

The evaluation team of IT and business 2.

executives (usually with an outside facilitator)

then used their individual ratings to converge on

an overall assessment level/score of maturity for

the organization. This process applied the model

as a descriptive tool.

The evaluation team then applied the next higher 3.

level of maturity as a prescriptive roadmap to

improve the alignment of IT and business by

identifying specifc opportunities for moving to

that next higher level.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Injection Molding Part CostingDokument4 SeitenInjection Molding Part CostingfantinnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- IBM - Data Governance Council - Maturity ModelDokument16 SeitenIBM - Data Governance Council - Maturity Modelajulien100% (3)

- BharatBenz FINALDokument40 SeitenBharatBenz FINALarunendu100% (1)

- Creating A Strategic IT ArchitectureDokument20 SeitenCreating A Strategic IT Architecturerolandorc0% (1)

- Experiencing MIS Notes On Chapters 1 - 7Dokument10 SeitenExperiencing MIS Notes On Chapters 1 - 7Andy Jb50% (4)

- Organization Development: Developing the Processes and Resources for High-Tech BusinessesVon EverandOrganization Development: Developing the Processes and Resources for High-Tech BusinessesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vault Guide To The Top Insurance EmployersDokument192 SeitenVault Guide To The Top Insurance EmployersPatrick AdamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- BUS835M Group 5 Apple Inc.Dokument17 SeitenBUS835M Group 5 Apple Inc.Chamuel Michael Joseph SantiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internal Quality Audit Report TemplateDokument3 SeitenInternal Quality Audit Report TemplateGVS RaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrated Talent Management Scorecards: Insights From World-Class Organizations on Demonstrating ValueVon EverandIntegrated Talent Management Scorecards: Insights From World-Class Organizations on Demonstrating ValueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Account StatementDokument46 SeitenAccount Statementogagz ogagzNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Ifma FMP PM ToDokument3 SeitenI Ifma FMP PM TostranfirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 6 EntrepreneurshipDokument13 SeitenLesson 6 EntrepreneurshipRomeo BalingaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resourse Management 1Dokument41 SeitenHuman Resourse Management 1Shakti Awasthi100% (1)

- A Theoretical Framework For Strategic Knowledge Management MaturityDokument17 SeitenA Theoretical Framework For Strategic Knowledge Management MaturityadamboosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Randy Gage Haciendo Que El Primer Circulo Funciones RG1Dokument64 SeitenRandy Gage Haciendo Que El Primer Circulo Funciones RG1Viviana RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misqe Sam Luftman - Dec-2007Dokument13 SeitenMisqe Sam Luftman - Dec-2007cristhian raul ortiz hilarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mitra Sambamurthy 2011Dokument13 SeitenMitra Sambamurthy 2011Niky Triantafilo NuñezNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIT CISR Wp397 DemandShapingSurveyDokument13 SeitenMIT CISR Wp397 DemandShapingSurveyAldus PagemakerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1bfinalLuftmanJIT2015 PDFDokument22 Seiten1bfinalLuftmanJIT2015 PDFmamun afifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic IT Alignment Maturity LevelsDokument49 SeitenStrategic IT Alignment Maturity LevelsSuhelPiramidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- B - It A: Usiness LignmentDokument9 SeitenB - It A: Usiness LignmentLuis Miguel Guzman ReateguiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mis Role & Importance, Corporate Planning of MISDokument6 SeitenMis Role & Importance, Corporate Planning of MISBoobalan RNoch keine Bewertungen

- IT InfrastructureDokument9 SeitenIT InfrastructurewilberNoch keine Bewertungen

- 112case1 Topic10Dokument33 Seiten112case1 Topic10王人風Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction and Background of The StudyDokument3 SeitenIntroduction and Background of The StudyMuqarrub Ali KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- COBIT GlossaryDokument7 SeitenCOBIT GlossarysunilNoch keine Bewertungen

- IT Governance On One Page Peter Weill Jeanne W. RossDokument18 SeitenIT Governance On One Page Peter Weill Jeanne W. RossDouglas SouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrative FrameworkDokument17 SeitenIntegrative Frameworkkatee3847Noch keine Bewertungen

- Information Technology'S Role in Organizations' Performance: Ebrahim Chirani Somayeh Moghim TirgarDokument7 SeitenInformation Technology'S Role in Organizations' Performance: Ebrahim Chirani Somayeh Moghim TirgarLabaran LucasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessing_Business-IT_Alignment_MaturityDokument52 SeitenAssessing_Business-IT_Alignment_MaturityRicardo FonsecaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Support For Information Management in Virtual OrganaizationDokument54 SeitenA Study On Support For Information Management in Virtual Organaizationsmartway projectsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business and IT Alignment Answers and QuestionsDokument16 SeitenBusiness and IT Alignment Answers and QuestionsCedric CedricNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enablers and Inhibitors of Business-It AlignmentDokument33 SeitenEnablers and Inhibitors of Business-It Alignmentkarellia8100% (1)

- A Review of IT GovernanceDokument41 SeitenA Review of IT GovernanceAdi Firman Ramadhan100% (1)

- Management Control and Information SystemDokument137 SeitenManagement Control and Information SystemBeatrice Zembere KuntembweNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIS (Final) Set 1Dokument14 SeitenMIS (Final) Set 1nigistwold5192Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shiv MB00Dokument11 SeitenShiv MB00Mohamed JumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Investigation On The Effect of Strategic Information System On The Improvement of The Implementation of Organizational StrategiesDokument9 SeitenAn Investigation On The Effect of Strategic Information System On The Improvement of The Implementation of Organizational Strategiessajid bhattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- It Governance Thesis TopicsDokument6 SeitenIt Governance Thesis Topicscatherineaguirresaltlakecity100% (2)

- MB0031 Set-1Dokument15 SeitenMB0031 Set-1Shakeel ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 1: Enterprise Resource Planning and Business Model Innovation: Process, Evaluation and OutcomeDokument8 SeitenArticle 1: Enterprise Resource Planning and Business Model Innovation: Process, Evaluation and OutcomeSonal GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bits Zc471Dokument23 SeitenBits Zc471mubashkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Information System PDFDokument6 SeitenManagement Information System PDFHashim HabeedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Information System Thesis PDFDokument5 SeitenManagement Information System Thesis PDFHelpWithCollegePapersUK100% (2)

- Mboo31 - Management Information Systems Set - 1 Solved AssignmentDokument10 SeitenMboo31 - Management Information Systems Set - 1 Solved Assignmentved_laljiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review of Related Literature Management Information SystemDokument3 SeitenReview of Related Literature Management Information SystemZelop DrewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business It Alignment Master ThesisDokument4 SeitenBusiness It Alignment Master Thesisgbwav8m4100% (2)

- 5 Journal Analysis-New1Dokument10 Seiten5 Journal Analysis-New1Kukuru HiruNoch keine Bewertungen

- IT Alignment in SMEs Should It Be With Strategy or PDFDokument13 SeitenIT Alignment in SMEs Should It Be With Strategy or PDFJSCLNoch keine Bewertungen

- E-Strategy: DBIT Pvt. Circulation Notes by Prof.S.P.Sabnis 1Dokument23 SeitenE-Strategy: DBIT Pvt. Circulation Notes by Prof.S.P.Sabnis 1Jayneel GajjarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrating Knowledge Management With Business Intelligence Processes For Enhanced Organizational LearningDokument10 SeitenIntegrating Knowledge Management With Business Intelligence Processes For Enhanced Organizational LearningOki Januar Insani MNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSF Implementing Business Inteligence in SME (Article) PDFDokument22 SeitenCSF Implementing Business Inteligence in SME (Article) PDFRock BandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Human Resource in Information TechnologyDokument18 SeitenRole of Human Resource in Information TechnologyKarthi KeyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Information System in IndiaDokument5 SeitenManagement Information System in IndiaAnkur TripathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Is Success Petter DeLone McLean 2008Dokument29 SeitenMeasuring Is Success Petter DeLone McLean 2008Adrien CaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Significance of MIS for Strategic PlanningDokument9 SeitenThe Significance of MIS for Strategic PlanningKukuru HiruNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Hribar Rajteric FinalDokument23 Seiten3 Hribar Rajteric Finalessamsha3banNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name Registration Number Mupfurutsa Clarence T. H1310020K Zenda Nigel W. H1312089Z Kuveya Kelvin T. H131KDokument8 SeitenName Registration Number Mupfurutsa Clarence T. H1310020K Zenda Nigel W. H1312089Z Kuveya Kelvin T. H131KTakudzwa S MupfurutsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answer All The Following Questions: CHAPTER TWODokument10 SeitenAnswer All The Following Questions: CHAPTER TWOAmiira HodanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Information System: Syllabus OverviewDokument136 SeitenManagement Information System: Syllabus Overviewneemarawat11Noch keine Bewertungen

- MSC International Management Dissertation TopicsDokument7 SeitenMSC International Management Dissertation TopicsWriteMyPaperCheapSiouxFallsNoch keine Bewertungen

- How BI and KM interact inside organizationsDokument11 SeitenHow BI and KM interact inside organizationsMd Mehedi HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Theory and PracticeDokument7 SeitenManagement Theory and Practicesumit86Noch keine Bewertungen

- MANAGEMENT THEORY AND PRACTICE: UNDERSTANDING CULTURAL DIMENSIONSDokument10 SeitenMANAGEMENT THEORY AND PRACTICE: UNDERSTANDING CULTURAL DIMENSIONSRohit GangurdeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Processes:: Information SystemDokument44 SeitenBusiness Processes:: Information SystemHani AmirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Intelligence Success Factors: A Literature Review: Journal of Information Technology ManagementDokument15 SeitenBusiness Intelligence Success Factors: A Literature Review: Journal of Information Technology ManagementNaol LamuNoch keine Bewertungen

- MB0031 Set - 1Dokument12 SeitenMB0031 Set - 1Abhishek GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Information systems - MIS: Business strategy books, #4Von EverandManagement Information systems - MIS: Business strategy books, #4Noch keine Bewertungen

- GPB Rosneft Supermajor 25092013Dokument86 SeitenGPB Rosneft Supermajor 25092013Katarina TešićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Plan For Bakery: 18) Equipment (N) 19) Working CapitalDokument10 SeitenBusiness Plan For Bakery: 18) Equipment (N) 19) Working CapitalUmarSaboBabaDoguwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamics AX Localization - PakistanDokument9 SeitenDynamics AX Localization - PakistanAdeel EdhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Mcqs On Revenue CycleDokument6 SeitenGeneral Mcqs On Revenue CycleMohsin Kamaal100% (1)

- CVP Solutions and ExercisesDokument8 SeitenCVP Solutions and ExercisesGizachew NadewNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIS - Systems Planning - CompleteDokument89 SeitenMIS - Systems Planning - CompleteDr Rushen SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Profitability in A Manufacturing Firm Bizzan ManufactuDokument2 SeitenCustomer Profitability in A Manufacturing Firm Bizzan Manufactutrilocksp SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3.cinthol "Alive Is Awesome"Dokument1 Seite3.cinthol "Alive Is Awesome"Hemant TejwaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pest Analysis of Soccer Football Manufacturing CompanyDokument6 SeitenPest Analysis of Soccer Football Manufacturing CompanyHusnainShahid100% (1)

- GPETRO Scope TenderDokument202 SeitenGPETRO Scope Tendersudipta_kolNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNV-08 Employer's Claims PDFDokument1 SeitePNV-08 Employer's Claims PDFNatarajan SaravananNoch keine Bewertungen