Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Conducting Literature Search RCN

Hochgeladen von

Bini ThomasOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Conducting Literature Search RCN

Hochgeladen von

Bini ThomasCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

p43-49w24

13/2/09

12:58 pm

Page 43

learning zone

CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Page 50 Mixed literature multiple choice questionnaire Page 51 Read Diana Murrys practice profile on pilonidal sinus disease Page 52 Guidelines on how to write a practice profile

Guidance on conducting a literature search and reviewing mixed literature

NS480 Price B (2009) Guidance on conducting a literature search and reviewing mixed literature. Nursing Standard. 23, 24, 43-49. Date of acceptance: November 25 2008.

Summary

This article sets out recommendations for conducting a review of different categories of literature, known as mixed literature.

Author

Bob Price is director, postgraduate awards in advancing healthcare practice, Open University, Milton Keynes. Email: altanprice@aol.com

Keywords

Literature and writing; Literature searching; Research These keywords are based on the subject headings from the British Nursing Index. This article has been subject to double-blind review. For author and research article guidelines visit the Nursing Standard home page at nursingstandard.rcnpublishing.co.uk. For related articles visit our online archive and search using the keywords.

and reviewing literature is a key skill. Developing policies and protocols, strategies for practice development, research design and preparing articles for publication or conference presentation are all underpinned by a good understanding of the literature. It helps us to locate a new initiative in its context and to examine new ideas (Steward 2004). If the literature is based on robust research we can feel confident in using it to develop our work. The literature is often mixed. This means that it has come from many different sources, has been written for different purposes and written in different contexts. It is necessary to make sense of mixed literature, interpreting what it tells us about the state of current knowledge.

Literature Aims and intended learning outcomes

THIS ARTICLE AIMS to help you conduct a literature search, review of mixed literature and to write a final description that incorporates different ways of examining what the literature tells us. After reading this article you should be able to: Plan an effective literature search strategy. Identify the most appropriate ways to review the different types of literature obtained. Explore ways to write up your evaluation of the literature as a whole. Reach an informed opinion on the ways that others have reviewed the literature. It can be difficult to plan a new nursing initiative when the state of healthcare knowledge seems so uncertain. However much we might wish that our practice is evidence-based, we have to accept that the knowledge base is often incomplete, fragmented and/or confused. There might be no single truth to rely on. Instead of one category of literature reporting on the world of health care there are, arguably, several and each of these has been written for a different purpose and with different sets of assumptions. Each category can present a different truth about what is central and important in nursing. For example, literature can be designed to report research and to present evidence emerging from completed studies (nursing as a science). However it might be polemical, arguing why health care should be delivered in a particular way (nursing as advocacy). In many circumstances literature is experiential and february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009 43

Introduction

Healthcare literature forms the basis of a great deal of work that nurses do, therefore searching NURSING STANDARD

p43-49w24

13/2/09

12:58 pm

Page 44

learning zone professional issues

invites readers to interpret or make sense of events or issues encountered in practice (nursing as a reflective, aesthetic or artistic process). There are different notions of truth, that which is valid, important, worthy and defensible (Harrison and McDonald 2008). Different categories of literature invite readers to engage with it in different ways perhaps examining arguments made or reflecting on whether they share the same philosophical view. Understanding each category of literature and identifying which articles operate in which category will help us to manage the process of reviewing the literature. It is important to recognise the purpose of the literature that we review to make sense of its contribution to our knowledge.

Time out 1

Select a healthcare topic for a literature review and consider which categories of literature make a contribution. The following list of categories should be helpful: Research is a systematic investigation to establish facts or principles. Theoretical proposes or explains a theory. Philosophical highlights how best to proceed, the issues for consideration, morally or ethically. Alternatively, that which espouses an ideology about what should happen. Experiential describes experience or offers a case study.

Research literature

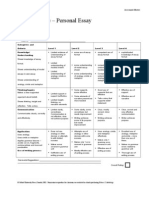

Research literature exists to report findings from individual studies, or a collection of studies (a meta-analysis) that help the reader to appreciate the volume and the quality of evidence supporting TABLE 1 Scientific paradigms

Research paradigm Typical research approaches

a particular area of healthcare practice (Johnson and Martinson 2007, Price and Thomas-Varcoe 2008). Research literature is influenced by different paradigms that affect the way projects are designed, their findings and the claims that the researcher might make (Crossan 2003, Brotchie et al 2008) (Table 1). Paradigms or world views are mindsets for the explanation of the world around us and can come to dominate how we think the world should be seen. Research conducted in the positivist paradigm focuses on empirical facts and the sorts of designs that help the researcher to assert something about a sample of participants. It might be used to infer how a larger population of people might behave. To use osteoporosis as an example, research conducted in the positivist paradigm could consist of a drug trial designed to improve the absorption of calcium, which might limit the risk of fractured hips in older people. Other research, that which has been conducted in the naturalistic paradigm, is designed to explore others experiences and behaviours in the natural context (Lee 2006). Researchers are eager to illuminate the experience and lives of others, rather than predict what will happen next or work best. Researchers working with different approaches in this paradigm for example ethnography and phenomenology work in subtly different ways. They share in common a belief that research needs to be conducted in the world as it is, rather than under controlled conditions or in a laboratory. An osteoporosis example might involve a study of people as they cope with the pain associated with deteriorating spinal vertebrae. Researchers working with the critical theory paradigm claim that no research can be completely objective and it is, therefore, more honest to conduct research that works to empower the disadvantaged (Brotchie et al 2008). A feminist study of women and their efforts to

Criteria for judging research claims Validity. Reliability. Checks for bias and the influence of intervening variables. Authenticity can the reader ascertain how the data were produced? Transferability does it help the reader explain experiences encountered elsewhere? Clarity or otherwise of the political assumptions underpinning research. Exposure of real issues blighting the lives of others.

Positivist carefully designed studies, Randomised controlled clinical trials. devised to scrutinise dispassionately Quasi-experimental designs. empirical data and theoretical explanations. Descriptive surveys using carefully constructed questionnaires, interview or observation schedules. Naturalistic explorative studies in natural Grounded theory. settings that help explain the ways in which Phenomenology. others behave. Some forms of case study, ethnography and qualitative data surveys. Critical theory theoretical or ideologically-driven enquiries designed to expose inequality and to help liberate others.

(Adapted from Brotchie et al 2008)

Feminist or Marxist forms of research, including critical theory-driven case studies and phenomenology. Action research.

44 february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009

NURSING STANDARD

p43-49w24

13/2/09

12:58 pm

Page 45

secure adequate support when dealing with postmenopausal osteoporosis falls into this category. The key point arising from this is that we need to appreciate what paradigm influences the research that we read. Understanding what the researcher believes to be important or true as indicated by his or her approach to research, helps us to evaluate the evidence and arguments he or she constructs.

patient advocacy following a fractured hip. The concern in such an article is not simply to counter the complications following such an injury and surgery, it is also about helping the patient back towards independence and feeling whole again.

Experiential literature

Much nursing literature is based on experience (Purkis and Bjrnsdttir 2006). Experiential literature is often written to help colleagues make sense of their own experiences. Case studies, reflective episodes or observations from practice are used to select the key features of what it is to deliver care in a certain way. There is no special claim made that what is shared applies to other patients and other situations, but the author highlights what he or she noted and invites readers to make comparisons with their own experience.

Theoretical literature

Theory serves a different purpose from research and is important in health care. It can, for example, offer concepts to help the reader think about the way in which care is designed and delivered. The concept of consumerism is an example, suggesting a collection of attitudes and values that could describe the orientation of patients to healthcare services. Theory-based literature often invites the reader to answer a number of questions such as, does this explain what is happening? Does this help us to access ideas or ways of working that might enhance nursing care? Could the ideas contained in it help us to improve nursing practice? Theory operates at different levels and some of it is designed to help nurses conceptualise what they do in a variety of contexts. Many of the nursing models that were first expounded in the 1980s set out to offer an explanation of what characterised the work of the nurse (Tierney 1998, Wimpenny 2002, Salvage 2006). It is easy to dismiss theory-based literature as being inferior to research but they often work closely together. For example, a theory might be developed that explains how individuals counter the risks associated with osteoporosis, and later a research study might test the theory, interviewing patients to understand their risk management strategies. Theorising is an appropriate and natural part of health care.

Time out 2

Make brief notes on how you might recognise literature that falls into each of the categories listed in Time out 1. Does some literature cross boundaries?

Planning an effective search strategy

An understanding of the different categories of literature available and their purpose can be put to good use when planning a literature search. We might wish to focus our interests from the outset, for example by choosing search terms that help us to secure a particular sort of article, such as a research article on osteoporosis prevention. In other situations, and especially where a subject is new and we suspect that there has been less written about it, we might prepare a wider variety of search terms in anticipation of securing the best balance of literature available. For example, we might conduct a series of searches, using search terms such as osteoporosis case study and osteoporosis care philosophy. Planning search terms in a more strategic way assists us to organise our enquiry and to defend what we say about that which is already known. We might then, for example, be able to conclude at the end of the review that a considerable amount of literature exists on the philosophy of care and that important points are made about how patients should be supported. Nurses are accustomed to setting a variety of other parameters when undertaking a literature search, for example which databases the search will take place in, whether it will also extend to websites and include a review of the textbook holdings of a library, what period will be included in the search (for example, the last five years) and february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009 45

Philosophical literature

Much healthcare literature is philosophical in nature and pertains to the values and beliefs associated with what it means to be healthy, ill and to care (Nyatanga 2005). Other philosophical literature deals with the dilemmas associated with delivering health care and with the practice or research decisions that need to be confronted, for example, Giblin (2002) and Gavrin (2007). Where literature is driven by strongly held professional or personal views, it can be described as ideological (Taylor 1997, Ellil et al 2007). Some of the literature on caring in nursing falls into this category and encourages colleagues to conceive their work in particular ways. There is, for example, a close association made between nursing and holism (Erickson 2007, Potter and Frisch 2007). We might imagine a philosophical article on NURSING STANDARD

p43-49w24

13/2/09

12:58 pm

Page 46

learning zone professional issues

in which languages articles will be read (often English) (Cronin et al 2008). It is useful to consider where articles and books that represent the sort of literature you are interested in might appear. It is important to note all of the search terms and the sources that we use and to then record the number of hits that are returned electronically for our search. The hits are those articles or books that are suggested as a possible match for the search terms that we have typed in. Recording the number of hits has several benefits. We can: Decide to refine our search terms to secure a more manageable number of articles to review. Gain a sense of how extensive the literature is. Start preparing an account of our enquiries that is included in the final report. The literature we are interested in does not always come from published sources. Much doctoral and masters degree research is not published but held in the collections of a university. We might also need to talk to professional colleagues to source policy and other documents that capture the ways in which the topic is understood. Different examples of literature can be found in different places.

Time out 3

What are the advantages and limitations of searching the literature for articles that have been written for different purposes? Is there merit in conducting a review of the philosophy of a particular aspect of care?

If, for example, the research has been designed in the positivist paradigm, the criteria usually applied are reliability and validity. One aspect to ascertain is whether it is likely that the results obtained are valid. Reliability refers to a judgement on whether the same research design might produce the same or similar results if it were replicated. It is important to be realistic about reliability as human subjects are conscious and aware of their responses to questions or the observations made of them in an experiment. In practice, it may be difficult to replicate a study or to avoid participants manipulating their responses in the future. Criteria associated with naturalistic paradigm research are different and usually refer to authenticity and transferability. To judge this we need a research audit trail (a clear account) of how the research was conducted and data secured, see for example, Montgomery and Bailey (2007). In critical theory paradigm research, we might ask whether the researcher has been clear about the theoretical or ideological assumptions that underpin the research. Having ascertained by what criteria we might evaluate the research studies found, we can proceed to test the claims against the data provided. We only have some of the data when we read a published article. A comprehensive scrutiny is only possible when we read the whole research report and are able to make comparisons with the raw data. It is encouraging when the researcher acknowledges the limitations of the study. Consideration of whether the evidence base provided through a collection of articles is complete and unambiguous (Price and ThomasVarcoe 2008) is termed a judgement call. There is no definition of what constitutes complete evidence. However, you should comment on: Where different conclusions and perspectives are presented by authors. Where contexts seem to have an important influence on findings. Where trends in findings seem to be emerging. Where new circumstances have arisen that could undermine what research findings can teach us. Where the literature seems to overlook an important facet of the topic perhaps indicating the need for additional work.

Reviewing research-based literature

Three important tasks are associated with the review of research literature: Deciding which criteria to use to evaluate the article in other words which paradigm to use. Testing whether the claims made in an article are supported by the evidence. Deciding whether the collection of articles provides complete and unambiguous evidence. The first is associated with the paradigm the research is located in and therefore the criteria by which claims associated with the research should be judged (Creswell 2002, Brotchie et al 2008). 46 february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009

Reviewing theory-based literature

Complex accounts have been given of how theories can be analysed, but here we will follow a more accessible approach and one that enables you to prepare an account alongside your review of the research articles. Theory provides us with NURSING STANDARD

p43-49w24

13/2/09

12:58 pm

Page 47

the concepts and processes to help us explain or examine a topic and they may or may not be clear (Siegert et al 2005, Edgar et al 2006). Concepts are the building blocks of theory, while processes describe how the concepts work together. So, for example, rehabilitation might be a theory made up of concepts, such as support, patient education and care planning. A rehabilitation process is that which brings these concepts together to produce a desirable end.

or do the majority of these articles offer broadly similar explanations of health care? From this we can sometimes sense what constitutes accepted wisdom.

Reviewing philosophy-based literature

We can think of several divisions of philosophical writing, among those related to ethics (moral decision making), that associated with aesthetics and values (what is worthwhile or valuable) and that associated with idealised forms of practice (ideology). While this remains a simplified description of a large category of literature, it does serve to remind us of some of the ways in which practice might be considered. In ethics, we consider principles of how we should behave (deontological) or, alternatively, the likely consequences of action or inaction (teleological) (Blackburn 2003). The reader is invited to consider arguments about the advantages and disadvantages of these as a basis for planning nursing action. Philosophy-based literature that discusses the philosophical base of nursing, and health care in general, introduces arguments that the reader is invited to evaluate and either support or reject. It might be argued that it is the nurses role to advocate the concerns of individual patients as part of delivering individualised care. While this is a moral argument, it is also associated with the definition of nursing and how we should practise. Although arguments are often balanced by counter arguments. In the above example the advocacy of one patient and his or her needs might involve compromises in the care provided for others. The most expert analysis of philosophy-based literature is likely to be carried out by philosophers who are versed in rhetoric (the process of debating ideas and arguments) (Tindale 2007). Questions are asked about such fundamental matters as what we can know and deduce from human experience. Nurses are required to make sense of philosophical literature so here we might establish what arguments are being made and what assumptions these are based on. As the articles often recommend what should be done, or what needs to be considered, it is important to ask why? Under what circumstances would the arguments be true and encourage us to support them? While research tells us about evidence (variously defined) and theory-based literature offers an idea of how health care could be viewed, philosophical literature might offer a vision of how healthcare practice should be perceived, or alternatively, alerts us to the discrepancies and challenges in understanding health care (Nyantanga 2005). For example, an article might contain a series of arguments about february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009 47

Time out 4

Return to the subject you identified in Time out 1 and note what concepts are important to explain it to other people. For example, in osteoporosis that might include: bone formation and degeneration, risk, risk management, pain, disability or impairment and endocrine control. It is only when the concepts and processes are clear and open to scrutiny that we can evaluate the theory. Do the concepts and processes describe the theory and indicate something of its usefulness in practice? A theory does not necessarily conform to the familiar; it can challenge us, propose an alternative and enhanced method of representing illness or health care. Nevertheless, the concepts and processes should be accessible. So, for example a theoretical article associated with osteoporosis might explain the ways in which womens experience of menopause and decisions made about hormone replacement therapy (HRT) start to shape the risk of osteoporosis that emerges later. That theory is accessible to the extent that it accounts for things that we know to be important in the way HRT is used, for example the composition of medication and the length of time that it is used. Where a theory seems to ignore something that we observe as being important and relevant in practice we can critique it. A series of questions can be asked including: Are the concepts described in this theory clear and, in our experience, relevant? Does the theory propose processes to explain change? Does the theory reflect our experience of delivering care or the needs and requirements of patients? If there are significant discrepancies, is this because the theory is inadequate or because we have become complacent? Does the theory challenge us, prompting further reflection and local investigation? Does a collection of theory-based articles offer competing explanations of what is happening, NURSING STANDARD

p43-49w24

13/2/09

12:58 pm

Page 48

learning zone professional issues

the holistic care of patients dealing with the after effects of a fractured hip. The success of that article rests largely on whether the author can demonstrate why this vision for care is necessary, desirable and sustainable. You can begin to evaluate philosophical literature by ascertaining: The chief assumptions of the article and whether these can be supported. The arguments are being made and whether these are clear and supportable. Whether the account of dilemmas and challenges (ethical literature) or ideology seems to fit with your experience of practice.

recommendations published by governments or royal colleges. While research often reports a planned change, and theory-based literature might suggest how change could be conceived, it is the experiential literature that offers the richest source of information about what it is like to deliver change (Purkis and Bjrnsdttir 2006). It often reflects the untidy nature of health care, what is involved in making sense of how best to proceed as we encounter different challenges. As nursing is a dynamic process, based on care relationships and changes in circumstance, it is important to capture this more fluid aspect of knowledge. If we have access to a large number of experiential accounts then we may be able to reflect on some trends.

Time out 5

Consider whether highlighting the way in which other reported experience contrasts with your own and provides insights into the process of care. Why might such a review complement that offered by the research, theoretical and philosophical categories of literature?

Reviewing experience-based literature

Historically, nursing journals published a large number of nursing care studies, accounts of support provided to patients that illustrated what care giving involved or what problems or patient needs were being met. Medical journals published accounts of treatment designed to alert colleagues to different ways of proceeding. More recently, nurses have been encouraged to report their reflections on practice, using one or other framework to describe the relationship between professional reasoning and care delivery (Lister and Crisp 2007). Because the authors of such work set out to describe local experience and practice it is inappropriate to evaluate these works in terms of their authority or truth. Large numbers of reflective accounts of practice can accumulate and some of these are very valuable because they incorporate useful accounts of patients. We might find such work represented on websites, especially those associated with patient support groups. Making sense of such literature involves two approaches that can help us to review what is being shared. Approach one We can begin by comparing the published accounts against local experience to identify any differences that exist between the two. Recognising what seems distinctly different about others experience, alerts us to what needs to be considered when delivering care ourselves. Sharply contrasting accounts of care remind us that practice is not universal. Differences in practice can relate to different healthcare systems, different cultures and organisational contexts, and available resources, but they can also prompt us to consider what seems better. Approach two We might then make further comparisons with best practice guidelines or 48 february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009

Writing a literature review

Where there is a large volume of mixed literature on a chosen topic, it is important to select at the outset what will be included in the review (Cronin et al 2008, Price and Thomas-Varcoe 2008). A review that covers each of the categories of literature outlined in this article can be longer than a review that deals solely with one, but it should not become unduly laborious simply because we have not ascertained at the start what we need to understand. It is better to break the review down into sections and to ask different questions of each category of literature (see questions listed under the heading Reviewing research-based literature on page 46). Having shared our observations in each of these areas you need to make conclusions about what the literature as a whole tells us. It is easy to make a mistake here and judge some of the literature as less rigorous and some as more robust. In practice, nursing needs to work with different types of literature that assure us about empirical evidence, and suggest new ways of thinking. The concluding points of the review should therefore refer back to the purpose and focus of the literature review. How complete is the account of the subject in the different categories of literature? Are there gaps or points of contention that warrant further NURSING STANDARD

p43-49w24

13/2/09

12:58 pm

Page 49

investigation or, at least, help us to explain why care-giving in that area seems so difficult? You might discover that significant tensions are uncovered. For example, experiential literature can report that nurses struggle to deliver the care they want. Nursing theory, however, espouses an idealistic way of viewing practice and this is reinforced by philosophical articles about moral nursing. Kirpal (2004) noted this tension when she examined nurses efforts to work closely with patients in a way they considered professional, but also had to attend to the priorities set by the organisation. In these circumstances the mixed literature review does not have to resolve the issue and decide what is right, but helps us to examine the relevant issues. A review offers a summary of knowledge development to date. Some areas of knowledge might have developed faster and seem richer as a result. Other literature will highlight where doubts remain. Even where more is debated than agreed it is possible to point to the richness and the complexity of the literature available. Simply appreciating this is important, as, for example, when we consider what multidisciplinary work

offers in the treatment of patients with osteoporosis. Where different professions describe problems in different ways and have made quite different assumptions about what is desirable, it is in the mixed literature, written by different practitioners, that we realise how much work remains.

Conclusion

While conducting a mixed literature review can seem a daunting task, it is possible to present information that works appropriately with your stated aims. We make sense of different categories of literature in different ways and therefore it is important to begin by understanding articles in terms of their respective purpose NS

Time out 6

Now that you have completed the article you might like to write a practice profile. Guidelines to help you are on page 52.

References

Blackburn S (2003) Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Brotchie J, Clark L, Draper J, Price B, Smith P (2008) K824 Designing healthcare research. Study guide. The Open University, Milton Keynes. Creswell JW (2002) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Second edition. Sage, Thousand Oaks, California CA. Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M (2008) Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step guide. British Journal of Nursing. 17, 1, 38-43. Crossan F (2003) Research philosophy: towards an understanding. Nurse Researcher. 11, 1, 46-55. Edgar R, Herbert R, Lambert S, MacDonald J, Dubois S, Latimer M (2006) The joint venture model of knowledge utilisation: a guide for change in nursing. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership (Toronto, Canada). 19, 2, 41-55. Ellil H, Vlimki M, Warne T, Sourander A (2007) Ideology of nursing care in child psychiatric inpatient treatment. Nursing Ethics. 14, 5, 583-596. Erickson HL (2007) Philosophy and theory of holism. Nursing Clinics of North America. 42, 2, 139-163. Gavrin JR (2007) Ethical considerations at the end of life in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 35, Suppl 2, S85-S94. Giblin MJ (2002) Beyond principles: virtue ethics in hospice and palliative care. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 19, 4, 235-239. Harrison S, McDonald R (2008) The Politics of Healthcare in Britain. Sage, London. Johnson M, Martinson M (2007) Efficacy of electrical nerve stimulation for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain. 130, 1-2, 157-165. Kirpal S (2004) Work identities of nurses: between caring and efficiency demands. Career Development International. 9, 3, 274-304. Lee P (2006) Understanding some naturalistic research methodologies. Paediatric Nursing. 18, 3, 44-46. Lister PG, Crisp BR (2007) Critical incident analyses: a practice learning tool for students and practitioners. Practice. 19, 1, 47-60. Montgomery P, Bailey PH (2007) Field notes and theoretical memos in grounded theory. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 29, 1, 65-79. Nyatanga L (2005) Nursing and the philosophy of science. Nurse Education Today. 25, 8, 670-677. Potter PJ, Frisch N (2007) Holistic assessment and care: presence in the process, Nursing Clinics of North America. 42, 2, 213-228. Price B, Thomas-Varcoe C (2008) K800 Dissertation: a research project. Study guide. The Open University, Milton Keynes. Purkis ME, Bjrnsdttir K (2006) Intelligent nursing: accounting for knowledge as action in practice. Nursing Philosophy. 7, 4, 247-256. Salvage J (2006) Model thinking. Nursing Standard. 20, 17, 24-25. Siegert RJ, McPherson KM, Dean SG (2005) Theory development and a science of rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation. 27, 24, 1493-1501. Steward B (2004) Writing a literature review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 67, 11, 495-500. Taylor JS (1997) Nursing ideology: identification and legitimation, Journal of Advanced Nursing. 25, 3, 442-446. Tierney AJ (1998) Nursing models: extant or extinct. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 28, 1, 77-85. Tindale CW (2007) Fallacies and Argument Appraisal. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Wimpenny P (2002) The meaning of models of nursing to practising nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 40, 3, 346-354.

NURSING STANDARD

february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009 49

p50w24

13/2/09

1:05 pm

Page 50

learning zone assessment

Mixed literature

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE AND WIN A 50 BOOK TOKEN

HOW TO USE THIS ASSESSMENT

This self-assessment questionnaire (SAQ) will help you to test your knowledge. Each week you will find ten multiple-choice questions that are broadly linked to the learning zone article. Note: There is only one correct answer for each question. Ways to use this assessment You could test your subject knowledge by attempting the questions before reading the article, and then go back over them to see if you would answer any differently. You might like to read the article to update yourself before attempting the questions. Prize draw Each week there is a draw for correct entries. Please send your answers on a postcard to: Zena Latcham, Nursing Standard, The Heights, 59-65 Lowlands Road, Harrow-on-the-Hill, Middlesex HA1 3AW, or send them by email to: zena.latcham@rcnpublishing.co.uk Ensure you include your name and address and the SAQ number. This is SAQ no. 480. Entries must be received by 10am on Tuesday March 3 2009. When you have completed your self-assessment, cut out this page and add it to your professional portfolio. You can record the amount of time it has taken. Space has been provided for comments and additional reading. You might like to consider writing a practice profile, see page 52.

c) Philosophy d) Randomised controlled trials

9. What criteria should be used for judging positivist research? a) Checks for bias b) Reliability c) Validity d) All of the above 10. What criteria should naturalistic research be judged against? a) Authenticity and transferability b) Grounded theory c) Reliability and validity d) Theoretical explanation This self-assessment questionnaire was compiled by Christine Walker The answers to this questionnaire will be published on March 4.

Report back

This activity has taken me ____ hours to complete.

1. Mixed literature can best be explained as being: a) Obtained from different sources b) Obtained from the same source c) Of differing quality d) Of poor quality 2. Nursing practice should be: a) Anecdotally based b) Evidence based c) Hypothetical d) Impractical

5. Ethnography and phenomenology are examples of: a) Empiricism b) Meta-analysis c) Naturalistic research d) Positivist research 6. Randomised controlled trials are examples of: a) Critical theory b) Descriptive survey c) Naturalistic paradigm d) Positivist research 7. An effective literature search should begin with: a) Choosing specific search terms b) Randomly searching databases c) Typing random questions into search engines d) Writing the final report 8. In which category of literature would ethics usually belong? a) Action research b) Experiential

Other comments:

3. Mixed literature includes which of the following categories: a) Experiential literature b) Philosophical literature c) Research d) All of the above 4. An account of findings from a collection of studies is a: a) Meta-analysis b) Paradigm c) Randomised controlled trial d) Survey

Now that I have read this article and completed this assessment, I think my knowledge is: Excellent Good Satisfactory Unsatisfactory Poor As a result of this I intend to:

Answers

The answers to SAQ no. 478 on isolation precautions, which appeared in the February 4 issue, are: 1. d 2. b 3. c 4. d 5. c 6. b 7. d 8. d 9. d 10. a

50 february 18 :: vol 23 no 24 :: 2009

NURSING STANDARD

Copyright of Nursing Standard is the property of RCN Publishing Company and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- (Len Barton) Education and Society 25 Years of THDokument385 Seiten(Len Barton) Education and Society 25 Years of THAndreea CraciunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mor Research ProposalDokument7 SeitenMor Research ProposalMikaella ManzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- HSL Contacting The Spiritual WorldDokument7 SeitenHSL Contacting The Spiritual WorldusrmosfetNoch keine Bewertungen

- GMAT CAT Critical ReasoningDokument2 SeitenGMAT CAT Critical ReasoningVishnu RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Materialism Vs SpiritualismDokument6 SeitenMaterialism Vs SpiritualismShashank TiwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Do We Study GeometryDokument33 SeitenWhy Do We Study GeometryLiviu Orlescu100% (1)

- Truth or Consequences Individuality, Reference, and The Fiction or Nonfiction DistinctionDokument11 SeitenTruth or Consequences Individuality, Reference, and The Fiction or Nonfiction DistinctionMoh FathoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPCH ActsDokument3 SeitenSPCH ActsJessa Peñano OdavarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christian ApologeticsDokument5 SeitenChristian ApologeticsAlbert Muya MurayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing Seminar Papers 1-10-2Dokument2 SeitenWriting Seminar Papers 1-10-2Skand BhupendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stages of Faith by James WDokument3 SeitenStages of Faith by James WKathzkaMaeAgcaoili100% (1)

- Design-Based Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational ChangeDokument5 SeitenDesign-Based Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational ChangeJoshua RuhlesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misita How To Believe in Nothing and Set Yourself FreeDokument165 SeitenMisita How To Believe in Nothing and Set Yourself FreeEsdfsd SdfsNoch keine Bewertungen

- This I Believe RubricDokument2 SeitenThis I Believe RubricDanika BarkerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Meaning in Context and Critical Reading StrategyDokument13 SeitenLiterary Meaning in Context and Critical Reading StrategyKelly Ace33% (3)

- Numerical: Lembar Kerja Peserta Didik Materi Aritmatika Sosial Dengan Model Pengembangan ThiagarajanDokument20 SeitenNumerical: Lembar Kerja Peserta Didik Materi Aritmatika Sosial Dengan Model Pengembangan Thiagarajandian kartikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aschenbrenner 1964-Aesthetics and Logic - An AnalogyDokument18 SeitenAschenbrenner 1964-Aesthetics and Logic - An AnalogyΧάρης ΦραντζικινάκηςNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business CommunicationDokument12 SeitenBusiness CommunicationwaqasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Milan Radulović, Religious Heritage in Serbian Literature (Part I)Dokument14 SeitenMilan Radulović, Religious Heritage in Serbian Literature (Part I)Stefan SoponaruNoch keine Bewertungen

- NICOLESCU The Idea of Levels of Reality and It Relevance For Non-Reduction and PersonhoodDokument13 SeitenNICOLESCU The Idea of Levels of Reality and It Relevance For Non-Reduction and PersonhoodDavid García DíazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 2Dokument19 SeitenLecture 2Arif ImranNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review of B. Alan Wallace's The Taboo of Subjectivity'Dokument8 SeitenA Review of B. Alan Wallace's The Taboo of Subjectivity'jovani333Noch keine Bewertungen

- Papers From Sheffiel Symposium On Urban LegendsDokument252 SeitenPapers From Sheffiel Symposium On Urban LegendsbronkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nag ArjunaDokument6 SeitenNag ArjunanieotyagiNoch keine Bewertungen

- BonJour, Ernest Sosa - Epistemic Justification Internal Ism vs. External Ism, Foundations vs. Virtues - WileyDokument248 SeitenBonJour, Ernest Sosa - Epistemic Justification Internal Ism vs. External Ism, Foundations vs. Virtues - WileyKave Behbahani100% (7)

- Cognitive PsychologyDokument22 SeitenCognitive PsychologySaeed Al-Yafei100% (6)

- A Conversation With Jean Luc MarionDokument6 SeitenA Conversation With Jean Luc MarionJavier SuarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRITICAL THINKING MOVEMENTDokument6 SeitenCRITICAL THINKING MOVEMENTmark_torreonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Einstein Quotes On SpiritualityDokument2 SeitenEinstein Quotes On Spiritualitybob jamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transdisciplinarity in Science and Religion, No 2, 2007Dokument336 SeitenTransdisciplinarity in Science and Religion, No 2, 2007Basarab Nicolescu100% (5)