Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Issues Management in The Information Planning Process

Hochgeladen von

9406513901Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Issues Management in The Information Planning Process

Hochgeladen von

9406513901Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Issues Management

Issues Management in the Information Planning Process

By: Benjamin Dansker Corporate Systems Analyst Reh. Rav Harlap 47 Jerusalem, Israel Janeen Smith Hansen Project Manager Massachusetts Port Authority 10 Park Plaza Boston, Massachusetts Ralph D. Loftin Management Consultant 60 White Pine Rd. Newton, Massachusetts Marlene A. Veldwisch Management Consultant Veldwisch Associates 9-4 Apple Ridge Rd. Maynard, Massachusetts

Many corporations have succeeded for years without much formal planning, relying instead on an annual budget cycle to set the stage for the foliowing year's activities. However, in a world of proliferating choices for technology; changing relationships among vendors, customers and competitors; rapid advances in information technology; and increased government involvement, the old way of doing business has quickly become obsolete. Today, a comprehensive MIS planning process has four distinct parts: 1. The development and management of a set of strategic technical objectives which address specific problems or opportunities facing the organization, or which position the organization to take advantage of new technologies. An applications plan, synchronized with the needs of the business. A systems architecture plan to assure the orderly and planned use of information technology. An issues management process to enable the organization to respond promptly and purposefully to unanticipated events, which is the subject of the remainder of this paper. We present this process, along with a critique based on the authors' experiences in developing and implementing issues management in a large MIS organization.

2. 3.

4.

Abstract

Major corporations have tried in recent years to formalize planning processes in their MiS organizations in response to the growing importance of information processing to corporate business functions. This paper examines the function of iong-range planning in an MiS organization with particular attention to the issues management process. This paper critiques the process, identifies both successes and difficulties, and suggests ways in which other organizations contemplating issues management might deveiop, implement, and maintain this component of the overall planning process. Keywords; Issues management, planning, iS management, management information systems ACM Categories: A.M., K.6., K.M.

Issues Management in the Context of Overall Organizational Goals

The development of the issues management process has as its primary purpose the achievement of three organizational goals: 1. To promote successful monitoring and evaluation of issues;

2. To involve MIS managers in the planning process; and 3. To bring the appropriate technical expertise to bear on broad planning questions.

Accomplishing the first goal enables the organization to adjust its activities to respond

MIS Quarterly/June 1987

223

Issues Management

appropriately to critical issues. Through the process of monitoring and evaluation, managers obtain an improved awareness of business issues, and unexpected demands on MIS resources are diminished. Furthermore, in the absence of a formal corporate planning process, the MIS issues management effort can provide a constructive focus on those items which threaten the MIS plan. The second organizational goal is to involve line MIS managers in the MIS planning process. The MIS planning process too often becomes the private (and sometimes irrelevant) domain of senior management, planning staff or the budget department. Assigning line managers responsibility for issues analysis, and acting on those analyses, demonstrates that senior MIS management regards planning as an important part of the routine work of every manager. The use of regular MIS senior staff meetings to conduct planning business is an important technique in helping to make planning more a part of the routine activity of every manager. By assigning issues analyses, discussing their results, and monitoring work related to issues at senior MIS staff meetings, the issues management process receives high visibility. Planning is made more immediate in the minds of MIS managers, and they are encouraged to increase their involvement In planning and to evidence their commitment to the process. The third organizational goal, to include technical experts in the issues management process, is partially a consequence of the highly technical environment. Broad based strategic issues often have significant and specific consequences for MIS managers with narrow, but complex areas of responsibility. By selecting the appropriate MIS managers to evaluate and monitor individual issues, the organization assures itself a more thorough, competent and complete analysis and also assures that the appropriate managers are aware of issues that may affect their activities. Although issues management often produces important findings and recommendations, these are not necessarily the most important products. As with any planning activity, the process itself serves as a catalyst. It serves to broaden the horizon of MIS managers, building their awareness of issues which extend

beyond parochial departmental concerns, while conditioning corporate management to the MIS effect on business issues.

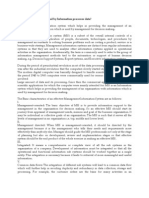

The Issues Management Process

Most companies who practice formal issues management are concerned largely with the effects of government legislation. These companies tend to view management as a broad corporate responsibility rather than the responsibility of a particular functional area. However, issues management can be more inclusive. It offers a straightforward and useful way for the MIS organization to deal with changes in the total environmenttechnical and business as well as legislative. For purposes of this article, an issue will be defined as anything which has the potential to cause unplanned work for the organization. The major purpose of issues management is to answer the question, "Does the issue appear to require any response by the organizationdoes the organization have to do any work related to this issue, either now or in the future?" If the answer is yes, then the work must be defined, assigned and managed. If the answer is no, then no more management time and attention should be given to the issue. In this way the rumors and concerns which often seem to overwhelm an organization can be reduced to those which demand an immediate commitment of resources. In many corporations the work of analyzing and evaluating issues and actions is not measured, yet it can occupy management and technical talent to such an extent that it threatens existing project commitments. Issues management focuses this work in those areas which have the highest potential payoff for the organization. The issues management process is depicted in Figure 1. The first step is issue identification. Issues come to light from a variety of sources: corporate publications; managers from other functional areas; newspapers and magazines; and simply rumors and concerns of the internal IS staff. Issues may represent threats, opportunities or both. Thus, the ap-

224

MIS Quarterly/June 1987

Issues Management

AVPS

MANAGERS

OTHERS

IDENTIFICATION

IS

PLANNING STAFF

PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS

DROP WATCH

ASSIGN ISSUES

IS SENIOR STAFF

IS PLANNING STAFF

REPORT PROGRESS

ANALYZE RECOMMEND PLAN

IS MANAGERS

REVIEW DEVELOP STRATEGIES DEVELOP STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES

IS SENIOR STAFF

DEVELOP TACTICAL PLANS MBOs

IS MANAGERS

Figure 1. Issues Management proach to the issue may be to minimize the damage or to maximize the opportunity. For example, an item of pending legislation related to mandated health benefits will impact the heaith care business. One can predict that the actuaries will require special studies using historical claims data to determine the effect on rates if the new legislation is enacted. If passed, such a bill might require claims and other systems to be modified to recognize the new benefits. For the MIS organization, an analysis of this issue might reveal opportunities to influence the effective date for the new benefits, or to appeal for a phased-in approach to provide time to accomplish the necessary program changes. Whatever the source, when an issue is identified it is brought to an MIS senior management staff meeting, usually by a planning staff person (more will be said later about the plan-

M/S Quarterly/June 1987

225

Issues Management

ning staff role). MIS senior management would include the senior MIS executive plus those who report directly to that position. This group would meet regularly with an agenda which wouid include a discussion of issues and their impacts. At that staff meeting, preliminary analysis is undertaken by the group with the help of a model known as an Issue Evaluation Aid. Several versions of this and similar models have appeared in planning literature, and the one which we have adapted for the MIS organization is depicted in Figure 2. This evaluation classifies issues according to their probability of occurrence and the degree of impact upon the organization, thus enabling the group to sort through a large number of issues which might otherwise be unmanageable.

For issues requiring further investigation, the second step in the process is to assign a particular line manager in the MIS organization responsibility for analyzing the issue further and for making recommendations to the senior MIS management group. To assist the managers in their analyses, a structured tool is recommended, referred to as "Guidance for Issues Management" and shown in Figure 3. This structured guidance has two primary advantages. First, communications and expectations are enhanced as the manager receiving the assignment is provided with the written definition and attributes of the issue as seen by senior MIS management. Second, comparison of issues is facilitated as all are subjected to a consistent analysis around the same impact areas.

Probability of Occurence High High Strategic Issues Low

Low

Figure 2. Issues Evaluation Aid The initial issue classification is generally performed without extensive formal research and is based largely on the MIS management group's own experience, knowledge, and judgement. The issues identified as strategic become the subject of further investigation. Most other issues are secondary and are reevaluated twice a year to see if any aspect has changed which would warrant reclassification. The exceptions are those which are considered unlikely to occur, but whose assumed impact is sufficiently great so as to warrant further investigation immediately. Again, the purpose of this initial screening by MIS senior management is to identify for the organization those issues which may require some responsethose for which the organization may have to either redirect some part of the current plan, or do new work. The manager selected to lead the analysis should be the person most knowledgeable in the issue subject area. If the issue is broad, other managers or technologists may be chosen for an analysis team. Persons may also be added to the team as a developmental experience, perhaps to expose them to some new business or technical area. It is important that the analysis be assigned with a short deadline, typically three weeks or less, and that the results of the analysis be in writing and limited to two or three pages. The short deadline is to avoid the "analysis paralysis" which can set in if too much time is provided. This is a preliminary analysis. The purpose is to understand more about the issue and the impacts, to allow the senior MIS managers to decide whether other resources need to be applied.

226

MIS Quarterly/June 1987

Issues Management

GUIDANCE FOR ISSUES MANAGEMENT ISSUE: Concise statement of the problem, opportunity, concern.

ATTRIBUTES: Consider the following characteristics as a minimum: Timing (urgency) Opportunity to Influence (mandated?) Input Data (more, different sources 1. 2. Output Data (more, faster, different users) Scope (corporate, single user) Processing (richer, faster)

Are the issue and attributes adequately defined? If not, redefine. Quantify the impacts to IS. How will the issue effect IS in the following areas? People Applications Organization structure Hardware Software Facilities Management methods -Budget

3. 4.

Identify near-term and long-term approaches which IS might take to soften the impact or maximize the opportunity. ' Deliver a brief (no more than three pages) report in weeks.

Figure 3. Guidance For Issues Management Requiring a brief written analysis provides an important record, and also leads the analysis team to be more thoughtful in the presentation of their findings. Often the descriptions and attributes of an issue will be clarified with key user personnel before preparing the analysis document. The analysis document is distributed to senior MIS management and planning staff, and subsequently discussed with the manager and the team who performed the analysis at an MIS senior staff meeting. Again, the focus of these discussions is to determine whether the organization should undertake any further work related to the issue. If so, the assignments are made and the work may be monitored by the same group. If no further assignments are to be made the issue should be dropped from the active list. An issue may also be dropped if the activity required to deal with it is incorporated as part of the routine work of a department. For example, a new applications system being developed as a result of an issue analysis may require no special review by the MIS senior staff. Assuming no unplanned work is required, the issue becomes inactive by definition. All issues removed from the active list for whatever reason should be marked for review at a periodic reassessment of all issues. If the issues analysis reveals that the MIS organization must perform unplanned work, this fact must be presented to an MIS resource management or priority setting committee. The presentation of issues analyses to these corporate groups provides a unique opportunity for the MIS organization to tie into broader business issues. The MIS organization is seen as having an awareness of the business, and top management is sensitized to the impact of the MIS organization on business conditions.

Implementation of the Process

Implementation of an issues management process in any organization necessarily will be an iterative activity. The purpose of this section is to identify four broad categories of problems which might be encountered by an

MIS Quarterly/June 1987

227

Issues Management

MIS organization attempting to build an issues management process, and to suggest how they might be handled:

Definition of roles and responsibiiities

One problem that can emerge early in the process is the lack of clearcut responsibility for issues management. The process is intended to be run largely by and for MIS managers. They are the people in the best position to analyze and solve problems related to issues. Planning staff support should be provided as a resource to the managers, to do research, coordinate and conduct meetings, and report the status of issues being addressed. The MIS executive and his/her direct reports should review the managers' work and decide what, if anything, should be done in response to the issues analysis. A primary challenge in the early stage is to gain acceptance for the process and to make MIS managers accountable for identifying and analyzing issues. MIS managers, already facing a seemingly insurmountable workload, can be expected to be unenthusiastic about involvement in issues management. Despite the fact that the MIS executive may profess strong support for issues analysis, there may seem to be no tangible incentives or rewards for managers to engage in creative problemsolving. Some senior MIS managers may also be skeptical about the issues management process, particularly given the volume of existing work to be done, and this skepticism may be apparent to lower level managers. The problem of motivation can be partially solved by having the planning staff take a more active role in driving the process. They can call upon managers who have been assigned issues for analysis to set up meetings, to volunteer to get information, and to become well versed in the issue so as to be able to contribute substantively to the analysis. In many cases the planning staff can convene and conduct meetings to discuss the assignment with all involved, and later assist in writing the analysis for the managers' review and approval. In this way, the planning staff makes the process easier for manager participation.

For smaller organizations who may not be able to afford dedicated planning staff, the assignment of part-time or temporary planning staff duties can be an important developmental opportunity for MIS managers, supervisors and individual contributors at all levels. The requisite interviewing and meeting facilitation skills are easily acquired and many employees welcome the opportunity to contribute outside their normal roles. The process also gains credibility with managers and others when the results of issues analyses begin to be presented to the MIS senior staff and, in some cases, to other executives in the corporation. The high visibility of results gives the process greater importance and managers feel some ownership and responsibility for their assigned issues.

Identifying and assigning issues

When the process is first undertaken everything seems to be an issue. Literally dozens can be identified through brainstorming sessions, surveys or other methods. The planning staff can help sort out this initial mass of Information by clustering those which relate to the same area of business or technology. Eventually though, the senior MIS management group must go through the list together and make an initial judgement as to which will be assigned to a manager for analysis. The approach to assigning these issues is critical. MIS senior management should resist the urge to mount an intensive effort to evaluate them all. It will be obvious to everyone that the organization could not respond to all issues, even if all the analyses were done, and such an effort will simply frustrate those whose analyses are not given serious consideration by management. A better approach is for the senior MIS management group to decide how many issues should be under anaiysis at any time. The initial set of issues is prioritized subjectively, using the Issue Evaluation Aid shown in Figure 2, and the agreed-upon top few assigned. As these issues are resolved, others can be assigned from the list in priority order. As new issues are identified, or as the status of existing issues changes over time, they can be placed on the list and assigned in accordance with their relative priority.

228

MIS Quarterly/June 1987

Issues Management

This approach assures that the top priority issues will receive the attention they deserve, and that the process will not burden managers unnecessarily. In addition, by constantly assigning issues, reviewing analyses, and discussing these with MIS and corporate management, planning work is taken out of the special, abstract, once-a-year realm and becomes more closely integrated with the daily work of every manager. The authors' experience is that for a large organization, several dozen issues will be identified at the beginning of the process and the initial screening will leave perhaps as many as twenty which should be assigned for analysis. It should be possible to resolve these in a few months (meaning to identify and assign any additional work which may be necessary). The senior MIS management group should be able to reach consensus on whether to assign a new issue with less than a one-hour discussion after the process has been working for a few weeks.

ardly. Even when the MIS executive openly supports the issues management process care must be taken not to delegate these important details to the planning staff. Assignment of responsibility for specific is sues should be decided collectively by the MIS senior management group. Each senior manager must be responsible for communi eating issues assignments directly to his/her managers, although the planning staff can be responsible for monitoring the status of those assignments. Managers' accountability for participating in the issues process can be for malized by making specific issues assignments a part of their routine performance reviews.

Breadth of issues

Perhaps one of the most difficult problems is the breadth of the issues. Many are seen as global and quite beyond the scope of MIS. and even of the corporation. Managers may be unable to assess what impact the issue might have and feel powerless to influence its direction or outcome. In most cases the MIS manager or managers responsible for the analysis possess a wealth of information about the company's business, as well as system capabilities and databases. Unfortunately, not many of them perceive the importance of their position or their ability to influence how an issue is seen by MIS management or by the company. Many are either overwhelmed by the current workload, or cynical about the organization's willingness to change and adapt to new issues in the MIS environment. However, by constructing their issue analysis carefully and presenting a good case to senior executives, these managers are in a powerful position to dictate how MIS can respond to a given issue in the future. The sense that an issue cannot be influenced will create ambivalence about the process. The risk is that the analysis will seem not only extracurricular, but pointless as well. In these cases there must be some acceptance that the process will not always result in clear proposals for dealing with complex issues, but will have value nonetheless by building awareness and provoking creative thought regarding an issue.

Issue analysis assignments

Everyone involved in the process will be frustrated if the analysis assignments given to the managers are fragmented and piecemeal. There must be standards set for what an issue analysis should cover, at what levei of detail it should address problems, how long it should be, and how much time should be spent. There must be clear expectations. Given the perceived lack of "credit" for time spent, the incentive for most managers may be to minimize the efforts in issue analysis. The "Guidance for Issues Management" shown in Figure 3 should be used to develop a standard format for analyzing each issue. The report to the MIS senior staff should be two to three pages, and might be acceptable either in outline or narrative form. The intended outcome of the analysis is an organized, consistent, systematic summary of facts, ideas and proposed solutions as a starting point for senior management discussion. A related problem is the lack of clarity regarding who should communicate the assignments, who should monitor status, and who should receive the complete assignment. Strategic issues naturally seem less important when these details are handled haphaz-

MIS Quarterly/June 1987

229

Issues Mar)agement

Conclusion

In conclusion, the authors present a series of recommendations designed to improve the likelihood of a successful issues management implementation, and insure that it can be maintained as an integral planning component. 1. When senior management begins to consider an issues management process, it should plan to involve line management early in the design of that process. This will allow line management to feel some ownership of the process, will help to clarify their concerns, and will reduce skepticism. 2. Senior management should recognize that building awareness of issues and encouraging involvement by lower-level managers are as important as the results of a specific issues analysis. 3. Line managers must not feel that their involvement in issues management is extracurricular, or done as a favor to someone. Involvement in the planning process, which includes issues management, must be an integral part of the line manager's work program and a component of his/her annual performance evaluation. It is clear that issues management can become one of the most important elements of the overall MIS planning process. However it is also the authors' experience that a successful issues management program can be developed and conducted with minimal frustration for the staff even where no overall planning framework exists.

About the Authors

Benjamin Dansker is a Corporate Systems Analyst at Luz Industries-Israel, a leader in the solar power field. He holds a Master of City and Regional Planning degree from Harvard University and a B.A. in Psychology from Emory University. His background includes transportation and environmental planning, and MIS strategic planning. Janeen Smith Hansen is a Project Manager in the Real Estate Development Department of the Massachusetts Port Authority. She holds a Master of City and Regional Planning degree from Harvard University and a B.A. in Social Science from Michigan State University. Her background includes extensive consulting and public sector experience in transportation system planning and analysis. Ralph D. Loftin is a Management Consultant specializing in planning and organizational effectiveness. He has more than 20 years experience in the management of information systems and services, including six years as Vice President of Data Processing Services for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts, He holds the B.S. and M.S. degrees In Electrical Engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology. He has authored numerous papers and articles and has spoken widely at National and International Conferences. He has served on the National Executive Council of the Society for Information Management, and was Chairman of the Boston chapter. He has taught at Georgia Tech, the University of Massachusetts and Babson College. He was appointed to the National Panel of Arbitrators in 1973. Marlene A. Veldwisch is a Management Consultant specializing in planning and health care management. She holds the M.B.A. in Strategic Planning and Organization Development from Boston College, and a B.A. in English from the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Her background includes strategic MIS planning and marketing research.

230

MIS Ouarterly/June 1987

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Dissertation On Performance Management System PDFDokument6 SeitenDissertation On Performance Management System PDFPayToWriteAPaperUKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research MethodologyDokument4 SeitenResearch MethodologykreanelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intro to Operations ResearchDokument8 SeitenIntro to Operations Researchermias alemeNoch keine Bewertungen

- BB0007 Management Information SystemsDokument29 SeitenBB0007 Management Information SystemsAshraf HussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- MC0076 Set 2Dokument7 SeitenMC0076 Set 2Ashay SawantNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Improve Strategic Planning - McKinsey & CompanyDokument4 SeitenHow To Improve Strategic Planning - McKinsey & CompanyAgnieszka KrawczykNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Science Final ExamDokument4 SeitenManagement Science Final ExamKristelle De VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mis Assignment PrintDokument10 SeitenMis Assignment Printvitazzz34Noch keine Bewertungen

- Planning and Cybernetic Control PaperDokument19 SeitenPlanning and Cybernetic Control PaperEka DarmadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Information System Assignment On Functional Areas at Different Levels Related To FinanceDokument12 SeitenManagement Information System Assignment On Functional Areas at Different Levels Related To FinanceAshad CoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 7. Strategy-ImplementationDokument27 SeitenChapter 7. Strategy-ImplementationAiralyn RosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Information Systems and Their Functionality in The Optimization of Business ProcessesDokument11 SeitenInformation Systems and Their Functionality in The Optimization of Business ProcessesTheo KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoritical Perspective (Chapter-01) (Class-02)Dokument15 SeitenTheoritical Perspective (Chapter-01) (Class-02)Sumon iqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- WIDE INFORMATION STRATEGY PLANNINGDokument6 SeitenWIDE INFORMATION STRATEGY PLANNINGMaria Therese PrietoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Egf Lesson 3cDokument7 SeitenEgf Lesson 3cChristine SondonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Strategic Management: Chapter OutlineDokument18 SeitenFundamentals of Strategic Management: Chapter OutlinealviarpitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Management Information Systems in Business Decision MakingTITLEDokument7 SeitenThe Role of Management Information Systems in Business Decision MakingTITLENishant AhujaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluating Improvement StrategyDokument6 SeitenEvaluating Improvement StrategyElla Mae SaludoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Balanced Scorecard For Small BusinessDokument22 SeitenA Balanced Scorecard For Small BusinessFeri100% (1)

- Corporate Knowledge Management SystemsDokument8 SeitenCorporate Knowledge Management Systemssymphs88Noch keine Bewertungen

- Information Sheet (IT Needs)Dokument35 SeitenInformation Sheet (IT Needs)Do DothingsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Science Lesson AutosavedDokument19 SeitenManagement Science Lesson AutosavedCygresy GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIS2Dokument10 SeitenMIS2Kapil KatukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management ScienceDokument2 SeitenManagement ScienceJianne AlegreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Management DefinitionDokument6 SeitenStrategic Management DefinitionFake ManNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Governance Using Balanced ScorecardDokument11 SeitenCorporate Governance Using Balanced Scorecardapi-3820836100% (2)

- Planning, Budgeting and Forecasting: Software Selection GuideDokument12 SeitenPlanning, Budgeting and Forecasting: Software Selection GuideranusofiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Planning Information System ModelDokument11 SeitenPlanning Information System ModelEddy ManurungNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Operation ResearchDokument4 SeitenWhat Is Operation ResearchAqua VixienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 - Ads460Dokument3 SeitenChapter 3 - Ads460Nur Diana NorlanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barrier #1: Difficult To Foster Collaboration Between Multiple StakeholdersDokument2 SeitenBarrier #1: Difficult To Foster Collaboration Between Multiple StakeholdersamuthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mari Vel CutieDokument10 SeitenMari Vel CutieJustine BatadlanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Info Systems Reflective EssayDokument5 SeitenBusiness Info Systems Reflective EssayMalcolm TumanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Management SystemDokument10 SeitenPerformance Management Systemzakuan79100% (1)

- Strategic ManagementDokument15 SeitenStrategic Managementnarumi07Noch keine Bewertungen

- Myat Pwint PhyuDokument10 SeitenMyat Pwint PhyuAung Kyaw Soe SanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Southeast University Southeast Business School MBA Program: Final Assessment Semester: Fall-2020Dokument42 SeitenSoutheast University Southeast Business School MBA Program: Final Assessment Semester: Fall-2020Farah TamjidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name Registration Number Mupfurutsa Clarence T. H1310020K Zenda Nigel W. H1312089Z Kuveya Kelvin T. H131KDokument8 SeitenName Registration Number Mupfurutsa Clarence T. H1310020K Zenda Nigel W. H1312089Z Kuveya Kelvin T. H131KTakudzwa S MupfurutsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Database System Concepts 6th EditionDokument15 SeitenDatabase System Concepts 6th EditiontrishaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coursework AssessmentDokument11 SeitenCoursework AssessmentSig SGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human resource planning processes and best practicesDokument17 SeitenHuman resource planning processes and best practicesnandini.vjyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11-Planning and Budgeting-Easing The Pain, Maximizing The Gain (Pages 65-72)Dokument8 Seiten11-Planning and Budgeting-Easing The Pain, Maximizing The Gain (Pages 65-72)newaznahianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management and StrategyDokument16 SeitenManagement and StrategyImran ShahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Swiss PAR Framework For Assessing Incentives in Results Based ManagementDokument11 SeitenSwiss PAR Framework For Assessing Incentives in Results Based ManagementRicardo Rosas LezamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 1 - MGT SciDokument14 SeitenLecture 1 - MGT SciJhunsam SamacoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit I: What Is Strategy?Dokument7 SeitenUnit I: What Is Strategy?anon-10224Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mid Term Answer PaperDokument12 SeitenMid Term Answer PaperMaliha FarzanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- System Planning and Investigation for Security IntegrationDokument9 SeitenSystem Planning and Investigation for Security IntegrationNaresh PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q1 Examine The Strategy Formulation Process in Detail.: Assignment 2Dokument10 SeitenQ1 Examine The Strategy Formulation Process in Detail.: Assignment 2AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christine Marie Ramirez - Activity - 2Dokument2 SeitenChristine Marie Ramirez - Activity - 2Christine Marie T. RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Planning Basics for FP&MDokument3 SeitenStrategic Planning Basics for FP&MatukbarazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Ms of ManagementDokument5 Seiten7 Ms of Managementnica100% (3)

- MIS (Final) Set 1Dokument14 SeitenMIS (Final) Set 1nigistwold5192Noch keine Bewertungen

- Q1. What Do You Understand by Information Processes Data? Ans:-MIS Is An Information System Which Helps in Providing The Management of AnDokument4 SeitenQ1. What Do You Understand by Information Processes Data? Ans:-MIS Is An Information System Which Helps in Providing The Management of Anbhandari0148Noch keine Bewertungen

- Strategy ImplementationDokument6 SeitenStrategy Implementationswatisingla786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Best Practices For Planning and BudgetingDokument20 SeitenBest Practices For Planning and BudgetingSilky SmoothNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Information - Critical Evaluation of Relevant IssuesDokument11 SeitenManaging Information - Critical Evaluation of Relevant IssuesZahra NabeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Information systems - MIS: Business strategy books, #4Von EverandManagement Information systems - MIS: Business strategy books, #4Noch keine Bewertungen

- AcknowledgementDokument2 SeitenAcknowledgement9406513901Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Case On Maruti Suzuki: Disha Patil Vibha Singh Priya Chavan Drishti Bhadra Shalki Rana Vaibhauv VijayDokument9 SeitenA Case On Maruti Suzuki: Disha Patil Vibha Singh Priya Chavan Drishti Bhadra Shalki Rana Vaibhauv Vijay9406513901Noch keine Bewertungen

- ODDokument2 SeitenOD9406513901Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lee Kun-HeeDokument4 SeitenLee Kun-Hee9406513901Noch keine Bewertungen

- Design Viewing Poject File Submitted by - Ananya SinghalDokument30 SeitenDesign Viewing Poject File Submitted by - Ananya SinghalRian vlogsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavioral Interview Fit MatrixDokument31 SeitenBehavioral Interview Fit MatrixAdithi RajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- McKinsey Response To RFPDokument73 SeitenMcKinsey Response To RFPQUEST96% (25)

- Math Project 2 - Math Literature ActivityDokument4 SeitenMath Project 2 - Math Literature Activityapi-240597767Noch keine Bewertungen

- SAS Skills For EmployabilityDokument4 SeitenSAS Skills For EmployabilityAdine Jeminah LimonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scope of Nle1109Dokument376 SeitenScope of Nle1109ericNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creative ThinkingDokument25 SeitenCreative Thinkingapi-203625970Noch keine Bewertungen

- VERITAS D1.7.1 BDokument171 SeitenVERITAS D1.7.1 BgkoutNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSC 413 AssDokument7 SeitenCSC 413 AssKc MamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brian Tracy Phoenix SeminarDokument2 SeitenBrian Tracy Phoenix SeminarIncriptat OnEarth50% (4)

- SE 2 Mid Term AssignmentDokument43 SeitenSE 2 Mid Term AssignmentliveforotherzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Big Data and Cognitive ComputingDokument10 SeitenBig Data and Cognitive ComputingRajesh MurugesanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Math101 - Modern WorldDokument16 SeitenMath101 - Modern WorldBRENT THEA ALVEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIC - NIC AnalysisDokument14 SeitenPIC - NIC AnalysistecnicaseplNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2-Problem Solving MethodsDokument63 SeitenChapter 2-Problem Solving MethodsBadrul Afif Imran89% (9)

- The Evolution of Geostatistics: G. Matheron and W.1. KleingeldDokument4 SeitenThe Evolution of Geostatistics: G. Matheron and W.1. KleingeldFredy HCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q8 IM06 FinalDokument39 SeitenQ8 IM06 FinalJb MacarocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training and DevelopmentDokument49 SeitenTraining and Developmentthehrmaven2013100% (1)

- What We Know About Effects of Sport and Elite Athletics On Child Development OutcomesDokument82 SeitenWhat We Know About Effects of Sport and Elite Athletics On Child Development Outcomesandreea_zgrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Research MethodologyDokument35 SeitenAdvanced Research Methodologyaiman_fatima69Noch keine Bewertungen

- DP Math Analysis Unit Plan - Number and Alegbra (Core SL-HL)Dokument8 SeitenDP Math Analysis Unit Plan - Number and Alegbra (Core SL-HL)Raymond Meris100% (1)

- Alsup 060417 PDFDokument1 SeiteAlsup 060417 PDFethanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Software Project Management Assignment 1Dokument5 SeitenSoftware Project Management Assignment 1Kanwar ZainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carte Cap2Dokument10 SeitenCarte Cap2Irina DumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electromechanical Engineering Technician 2010Dokument16 SeitenElectromechanical Engineering Technician 2010Aman BrarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wild RiftDokument8 SeitenWild RiftKomal AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infant Toddler Child DevelopmentDokument5 SeitenInfant Toddler Child DevelopmentBrookeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Science LectureDokument22 SeitenManagement Science LectureDianne LawrenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- BBW Nicer Work ReportDokument32 SeitenBBW Nicer Work Reportrahib203Noch keine Bewertungen