Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Artigo Wo 2000

Hochgeladen von

Carmem Lúcia PergherOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Artigo Wo 2000

Hochgeladen von

Carmem Lúcia PergherCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Apical terminus location of root canal treatment procedures

Min-Kai Wu, MD, MSD, PhD, a Paul R. Wesselink, DDS, PhD, b and Richard E. Walton, DMD, MS, c Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Iowa City, Iowa ACADEMIC CENTREFOR DENTISTRYAMSTERDAM (ACTA)AND UNIVERSITYOF IOWA, COLLEGE OF DENTISTRY

The apical termination of root canal treatment is considered an important factor in treatment success. The exact impact of termination is somewhat uncertain; most publications on outcomes are based on retrospective findings. After vital pulpectomy, the best success rate has been reported when the procedures terminated 2 to 3 mm short of the radiographic apex. With pulpal necrosis, bacteria and their byproducts, as well as infected dentinal debris may remain in the most apical portion of the canal; these irritants may jeopardize apical healing. In these cases, better success was achieved when the procedures terminated at or within 2 mm of the radiographic apex (O to 2 mm). When the therapeutic procedures were shorter than 2 mm from or past the radiographic apex, the success rate for infected canals was approximately 20% lower than that when the procedures terminated at 0 to 2 mm. Clinical determination of apical canal anatomy is difficult. An apical constriction is often absent. Based on biologic and clinical principles, instrumentation and obturation should not extend beyond the apical

foramen. (Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;89:99-103)

Canal instrumentation includes both cleaning and shaping. Cleaning is the significant reduction of tissue as well as micro-organisms and their by-products from the pulp system. With a vital pulp, micro-organisms would not be present in the apical part of the canal. In infected cases, bacterial contamination may reach the most apical part of the canal 1-3 and occasionally the periapex. 4-8 The purpose of shaping during instrumentation is to create a canal configuration suitable for obturation. Ideally, instrumentation should terminate at a suitable location, which is not necessarily the same for both vital and infected cases. If the termination is too short or too long, the outcome is negatively influenced. Obturation and restoration prevent the reinfection of the pulp space by micro-organisms from the oral cavity, to seal all portals of exit and to serve as a wound dressing against which healthy tissue can oppose. Sealers are toxic, and their irritative effects increase as the material/tissue contact surface area increases. 9 Because obturating materials (particularly sealers) may elicit sensitivity and immune responses when in contact with vital tissues, 10 they should remain in the canal to minimize contact surface and irritative effects. 11-14 Furthermore, theoretically, a small contact surface may reduce the risk of leakage as a result of less material/canal wall interface. aLecturer. bprofessor and Chairman, Departmentof CariologyEndodontology Pedodontology,AcademicCentre for DentistryAmsterdam(ACTA), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. cprofessor,Departmentof Endodontics, Universityof Iowa, College of Dentistry,Iowa City, Iowa. Received for publication Feb 2, 1999; returned for revision Mar 16 and June 15, 1999; acceptedfor publication July 10, 1999. Copyright 2000 by Mosby,Inc. 1079-2104/2000/$12.00 + 0 7/151101618

On the other hand, the extension of the root filling should not be too short. If the apical canal is not completely obturated, residual bacteria may survive and multiply1; tissue fluids percolating into the canal may provide nutritive substrate. The apical 3 mm of the root canal system has been considered to be a critical zone in the treatment of infected root canal. 15

PROGNOSIS STUDIES

In 1994, Stabholz et a116 summarized the factors influencing the success and failure based on a series of mainly retrospective studies. No influence was found for most therapeutic factors, such as number of treatment sessions, type of interappointment intracanal medicament, type of filling material, obturation technique, etc. All studies agreed, without exception, that the extension of the filling material indeed influenced the treatment outcome. 16 However, the analyses were based solely on radiographic findings, which may not coincide with histologic healing. 17-19 In addition, no adequate statistical tests were applied to investigate the simultaneous influence of several potential factors on treatment outcome. 2 However, these studies together form a very large sample; the influence of other factors may be similar in the subgroups of over-, under-, and flush-extended root fillings. Therefore, the same conclusion reached in all these studies is likely a correct observation: prognosis is decreased with overfill and with significant underfill.

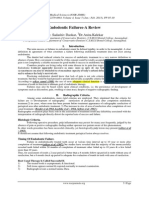

ANATOMY OF THE APICAL CANAL The apical anatomy of the root canal system (Fig 1) is important in understanding the principles of root canal treatment (RCT). The traditional classical concept of 99

100 Wu, Wesselink, and Walton

ORAL SURGERY ORAL MEDICINE ORAL PATHOLOGY January 2000

root canal

dentin

cementum _ Apex

Fig 1. Concept of the apex. Distance between the 2 landmarks, the apical constriction (AC) and the apical foramen (AF), and the true apex varies in each root considerably. The presence, location, and relationships of the AC to the AF is more theoretical than actual.

this anatomy is from Kuttler. 21 He found that usually the root canal narrowed toward the apex and expanded to form the apical foramen (AF). Further, the narrowest part of the canal formed the apical constriction (AC), just short of the AE However, in another publication, 22 the "traditional" single AC was found in less than half of the teeth. Frequently, the very apical portion of root canal was tapered or parallel. 22 Other authorslS, 23 had suggested that often no AC is present, particularly with apical pathosis and root resorption.15, 23 The classic concept (Fig 1) is also that the AC forms the minor foramen (or minor diameter)24; the most apical opening of the root canal is designated the AF or major foramen or greater diameter. 24 In reality, in more than 60% of the canals, the AF is not located at the apex, and the distance between the AF and the radiographic apex varies from 0 to 3.0 mm.21,22,z4-27The conclusion is that the classic apical canal anatomy, as shown by Kuttler, 21 is more conceptual than actual. The AC is commonly advocated as the ideal termination for RCT, being a natural narrowing of the root canal and almost at the termination of the pulp. This is supposedly where an apical stop is formed, against which the obturation materials are packed. Because this constriction is usually not present, the AF may be a more useful landmark. The distance between the AC (when present) and the AF ranges from 0.5 to 1.0 m m for teeth of different ages.21,22, 24-27 When the AF is located, the position of the AC (if it exists) can be estimated; if the AC is not present, the preparation and obturation will usually be within the confines of the root. In fact, it is difficult to locate either the AC or the AF clinically. Usually visible radiographically is the root apex. Although 0.5 to 1 mm short of the radiographic apex is commonly used as the termination point, this is only an estimate. It is an attempt to debride and obtu-

rate close to the AF but hopefully, not beyond. Obviously, this will often not be the outcome.

TERMINATION POINT WITH A VITAL PULP

With an irreversible pulpitis (vital pulp), bacteria (if present) are usually limited to the chamber. Instrumentation apically is to remove the noninfected tissue and to shape the canal. For these cases, the favorable point to terminate instrumentation and to form an apical stop appears to be 2 to 3 mm short of, rather than 0 to 2 mm from, the apex. 12,28 This principle (partial pulpectomy) was originally proposed by Davis 29 in 1922. He suggested preservation of vital pulp apically, often referred to as the apical pulp stump. Following this principle, a good success rate was obtained by Kerekes and Tronstad 28 and by Sjrgren et al.12 Therefore, for vital cases, the biologic and clinical evidence indicates it is unnecessary to terminate the procedures close to the AF. When the apical pulp stump remains, extrusion of irritating filling materials into the periradicular tissues may be prevented, thereby favoring apical healing. 14 Apparently, the reaction of the pulp stump to the filling materials will not negatively influence the health of periapical tissues. The concept that the apical periodontium should not be challenged with the extrusion of root canal filling materials beyond the end of the canal is supported by many authors. 30

TERMINATION POINT FOR INFECTED CANALS

Infected canals likely differ from teeth with vital pulps. In addition to removal of necrotic tissue and debris, an important goal is to reduce or eliminate bacteria. Because it is unknown how many bacteria remaining in the apical portion of the root canal can be managed by host defenses, instrumentation length should presumably not be shorter than the apical level

ORAL SURGERY ORAL MEDICINE ORAL PATHOLOGY Volume 89, Number 1

Wu, Wesselink, and Walton 101

"-:)." ~'.{

dentin debris

A

I II

Fig 2. Recapitulation to the working length with a small file. A, Dentin debris may shorten the working length and plug the canal at and beyond the working length. B, Recapitulation with a small file will aid in maintaining the full working length; the canal beyond the working length may still be plugged by debris.

of bacteria. Bacteria may remain sealed in the rootfilled canals of many radiographically successful cases. 31 As long as there is no pathway of bacteria or bacterial by-products to the periapex, a periapical response will not develop. If an avenue is later established, a nutritional (substrate) supply will develop, bacteria will proliferate and an inflammatory reaction may ensue. Canals with necrotic pulp tissue with or without periradicular pathosis are treated as infected canals. % An approach is to evaluate the correlation between the termination point and the success rate of infected canals by using the data from only those cases with pretreatment radiolucencies. These are likely the cases with infected canals32; the change in size of the lesion after treatment is assessed radiographically. A definite correlation between the radiographic and histologic findings has been reported for the teeth with pretreatment apical radiolucencies only. 33 Importantly, a tooth with no apical radiolucency before treatment may actually have an apical pathosis that is not radiographically visible. 34 Therefore, information about the change in lesion size after the treatment may not be provided by the radiographs if the lesion remains invisible. Perhaps this is why no definite correlation between the radiographic and histological findings could be found for the teeth without pretreatment apical radiolucencies. 33 The best success for treatment of teeth with necrotic pulps has been recorded when RCT was terminated at or within 2 m m of the radiographic apex (0 to 2 mm) for infected canals with visible apical pathosis. However, statistically significantly lower success was recorded

when treatment terminated short of 2 mm from, or was beyond the radiographic apex. 12,28,35 When procedures were more than 2 m m short of the apex, a significant reduction in success rate was recorded. 12,26 An interpretation is that the apical canal may harbor a critical count of microorganisms that would maintain periradicular inflammation. Thus, instrumentation is preferred to a level deep enough to remove or at least significantly reduce these microorganisms. During instrumentation, dentinal debris, which may be infected, is produced and may remain within the apical canal or in the periapical tissues. 1 In the canal, this debris may reduce the working length and may hinder repair. 36,37 In a study 37 of periradicular biopsies, extruded dentin debris or other materials often was associated with surrounding inflammation. These debris or materials were related to a history of RCT or apicoect0my. Why dentin chips cause periradicular inflammation 36,37 should be further studied. Recapitulation to the working length only may maintain the working length but not remove the dentinal debris that have plugged the canal beyond the working length (Fig 2). It presumably would be preferable to prevent plugging of dentinal debris in the apical portion of the canal, although it is unknown whether this debris (infected or uninfected) constitutes a significant irritant. With the use of instrumentation, techniques that involved a rotational motion, such as the balanced force, Canal Master U, Lightspeed and ProFile techniques 38,39 and frequent irrigation in sufficiently enlarged apical canals 4 have been found to be efficient in reducing accumulated dentinal debris in the apical canal.

I02

Wu, Wesselink, and Walton

ORAL SURGERY ORAL MEDICINE ORAL PATHOLOGY January 2000 bacteremia often is the result of overinstrumentation of teeth with necrotic, b a c t e r i a l l y c o l o n i z e d pulp spaces. 5 Although there is no definitive evidence that introducing bacteria or antigens from infected canals into the bloodstream causes systemic diseases, it would seem prudent to avoid this situation when possible.

A n o t h e r technique to enlarge and clean the apical canal is "apical clearing?' Parris et al,41 after step-back filing, used successively larger files a few sizes larger than the master apical file with a reaming motion; this technique did indeed enlarge and further debride the apical canal with less debris accumulation. One suggested approach to solve the problem is the "apical patency" concept. This is using a very small size file (10 or 15) to 1 m m longer than the final working length in an attempt to remove the dentinal debris from the very apical portion of the canal. This concept is taught in 50% of the United States dental schools. 42 However, the efficacy o f using a small file to remove the debris remains to be evaluated. Considering the apical canal anatomy, this approach seems unreasonable. If the patency file extends to the radiographic apex, 43 usually the instrument will go beyond the A F because the A F is usually located short of the apex. 21,22,25-27 The further the deviation of the A F from the apex, the further the instrument will penetrate and damage apical periodontium. In addition, the small file will likely not remove significant amounts o f debris. Again, this apical patency concept remains untested.

SUMMARY

Because most publications on outcomes are retrospective, definitive conclusions are not possible. Based on current information, the apical termination point of root canal treatment procedures seems to be an important influence on treatment outcomes. F o r teeth with vital pulps, leaving an apical pulp stump of up to 3 m m is recommended. For the infected canals, the length of root canal instrumentation should ideally not be short of the level to which bacteria have contaminated; locating the A F is of more importance, but it is difficult to accomplish. The final length for a few cases in which root canal therapy has failed and the failure m a y be related to infection in the very apical part of the canal, is to the AF; admittedly, the exact level of the A F cannot be determined with certainty. In conclusion, b a s e d on b i o l o g i c a l principles and experimental evidence, instrumentation or obturation should not extend beyond the apical foramen. These r e c o m m e n d a t i o n s m a y change as additional wellcontrolled, outcome-assessment studies are published.

TERMINATION POINT FOR RETREATMENT

W h e n present, the AC is the narrowest diameter of the blood supply. Apically, the canal widens and m a y have a richer b l o o d supply that m a y allow better i m m u n e activities than in the pulp canal. However, bacteria m a y s o m e t i m e s persist in the canal 44 and survive b e y o n d the AC; a speculation is that these bacteria are related to R C T failures. 1 It seems that it would be preferable to clean the canal to the A F in retreatment; the downside is the possibility of overinstrumentation, which would force materials and debris into periradicular tissues. In order to reduce the introduction of irritants into the periapex, a suggestion is to clean the coronal part of the root canal first with a step-down or crown-down sequence 45 with copious irrigation. However, instrumentation extended beyond the radiographic apex, which certainly would have its apical terminus beyond the AF, has been found to hinder apical healing significantly.4648 Although instrumentation to the A F is suggested for some failure cases, usually the apical stop should be created at 1 to 2 m m short of the A F to confine the instruments, irrigants, and obturants to the canal space.

REFERENCES

1. Nair PNR, Sjrgren U, Krey G, Kahnberg K-E, Sundqvist G. Intraradicular bacteria and fungi in root-filled asymptomatic human teeth with therapy-resistant periapical lesions: a longterm light and electron microscopic follow-up study. J Endod 1990;16:580-8. 2. Baumgartner JC, Falkler WA. Bacteria in the apical 5 mm of infected root canals. J Endod 1991;17:380-3. 3. Walton RE, Ardjmand K. Histological evaluation of the presence of bacteria in induced periapical lesions in monkeys. J Endod 1992;18:216-21. 4. Sundqvist G, Reuterving C-O. Isolation of Actinomyces israelii from periapical lesion. J Endod 1980;6:602-6. 5. Weir JC, Buck WH. Periapical actinomycosis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982;54:336-40. 6. Borssen E, Sundqvist G. Actinomyces of infected dental root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1981;51:643-8. 7. Tronstad L, Barnett F, Riso K, Slots J. Extraradicular endodontic infections. Endod Dent Tranmatol 1987;3:86-90. 8. Nair PNR. Light and electron microscopic studies of root canal flora and periapical lesions. J Endod 1987;13:29-39. 9. Meryon SD. The influence of surface area on the in vitro cytotoxicity of a range of dental materials. J Biomed Mater Res 1987;21:1179-86. 10. Kallus T, Hensten-Pettersen A, Mjrr IA. Tissue response to allergenic leachables from dental materials. J Biomed Mater Res 1983; 17:741-5. 11. Seltzer S, Turkenkopf S, Vito A, Green D, Bender IB. A histologic evaluation of periapical repair following positive and negative root canal cultures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1964;17:507-32.

SYSTEMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Concerns have recently been raised relative to the impact o f oral conditions on systemic health. 49 The impact may be by bacterial or immunogenic seeding of distant organs or tissues v i a the vascular ( b l o o d or l y m p h a t i c ) system. It has been d e m o n s t r a t e d that a

ORAL SURGERY ORAL MEDICINE ORAL P A T H O L O G Y

Wu, Wesselink, and Walton 103

Volume 89, Number 1

12. Sj0gren U, Hagglund B, Sundqvist G, Wing K. Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod 1990;16:498-504. 13. Nair PNR, Sj0gren U, Krey G, Sundqvist G. Therapy-resistant foreign body giant cell granuloma at the periapex of a root-filled human tooth. J Endod 1990;16:589-95. 14. Ricucci D, Langeland K. Apical limit of root-canal instrumentation and obturation. Int Endod J 1998;31:384-409. 15. Simon JHS. The apex: how critical is it? Gen Dent 1994;42:330-4. 16. Stabholz A, Friedman S, Tamse A. Endodontic failures and retreatment. In: Cohen S, Burns RC. editors. Pathways of the pulp. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1994. p. 690-728. 17. Brynolf I. A histological and roentgenological study of the periapical region of human upper incisors. Odont Revy 1967;18(Suppll 1):1-97. 18. Rud J, Andreasen JO, Jensen JEM. Radiographic criteria for the assessment of healing after endodontic surgery. Int J Oral Surg 1972;1:195-214. 19. Green TL, Walton RE, Taylor JK, Men'el P. Radiographic and histologic periapical findings of root canal treated teeth in cadaver. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1997;83:707-11. 20. Weiger R, Axmann-Krcmar D, Ltst C. Prognosis of conventional root canal treatment reconsidered. Endod Dent Traumatol 1998;14:1-9. 21. Kuttler Y. Microscopic investigation of root apexes. J Am Dent Assoc 1955;50:544-52. 22. Dummer PMH, McGinn JH, Rees DG. The position and topography of the apical canal constriction and apical foramen. Int Endod J 1984;17:192-8. 23. Coolidge ED. Anatomy of the root apex in relation to treatment problems. J Am Dent Assoc 1929;16:1456-65. 24. Gutmann JL. Problem solving in endodontic working-length determination. Compendium 1995;16:288-302. 25. Chapman CE. A microscopic study of the apical region of human anterior teeth. J Br Endod Soc 1969;3:52-8. 26. Palmer MJ, Weine FS, Healey HJ. Position of the apical foramen in relation to endodontic therapy. J Can Dent Assoc 1971 ;8:305-8. 27. Burch JG, Hulen S. The relationship of the apical foramen to the anatomic apex of the tooth root. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1972;34:262-8. 28. Kerekes K, Tronstad L. Long-term results of endodontic treatment performed with a standardized technique. J Endod 1979;5:83-90. 29. Davis W. Pulpectomy vs pulp-extirpation. Dental Items of Interest 1922;44:81-100. 30. Gutmann JL, Witherspoon DE. Obturation of the cleaned and shaped root canal system. In: Cohen S, Burns RC. editors. Pathways of the pulp. 7th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1998. p. 258-361. 31. Molander A, Reit C, Dahlen G, Kvist T. Microbiological status of root-filled teeth with apical periodontitis. Int Endod J 1998;31:1-7. 32. Sundqvist G. Bacteriological studies of necrotic dental pulps [PhD thesis]. Umegt University, Sweden, 1976. 33. Bender IB, Seltzer S, Soltanoff W. Endodontic success: a reappraisal of criteria: I and II. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1966;22:780-802. 34. Bender IB, Seltzer S. Roentgenographic and direct observation of experimental lesions in bone: I. J Am Dent Assoc 1961 ;62:152-60. 35. Bystr0m A, Happonen R-P, Sjtgren U, Sundqvist G. Healing of periapical lesions of pulpless teeth after endodontic treatment with controlled asepsis. Endod Dent Traumatol 1987;3:58-63. Holland R, De Souza V, Nery MJ, de Mello W, Bernabe PFE, Otoboni Fiho CD. Tissue reactions following apical plugging of the root canal with infected dentin chips. A histologic study in dogs' teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1980;49:366-9. Yusuf H. The significance of the presence of foreign material periapically as a cause of failure of root treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982:54:566-74. McKendry DJ. Comparison of balanced forces, endosonic, and step-back filing instrumentation techniques: quantification of extruded apical debris. J Endod 1990;16:24-7. Reddy SA, Hick ML. Apical extrusion of debris using two hand and two rotary instrumentation techniques. J Endod 1998;24:1803. Wu M-K, Wesselink PR. Efficacy of three techniques in cleaning the apical portion of curved root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1995;79:492-6. Parris J, Wilcox L, Walton R. Effectiveness of apical clearing: histological and radiographical evaluation. J Endod 1994;20:21924. Cailleteau JG, Mullaney TP. Prevalence of teaching apical patency and various instrumentation and obturation techniques in United States dental schools. J Endod 1997;23:394-6. Buchanan LS. Management of the curved root canal. Can Dent Assoc J 1989;17:40-7. Danin J, Linder L., Lundqvist G, Ohlsson L, Ramsktld L. Stri3mberg T. Outcome of periradicular surgery in cases with apical pathosis and untreated canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Radiol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;87:227-32 Goerig LAC, Michelich RJ, Schultz HH. Instrumentation of root canals in molars using the step-down technique. J Endod 1982;8:550-4. Seltzer S, SoltanoffW, Smith J. Biologic aspects of endodontics. V. Periapical tissue reactions to root canal instrumentation beyond the apex and root canal filling short of and beyond the apex. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1973;36:725-37. Bergenholtz G, Lekholm U, Milthon R, Engstrom B. Influence of apical overinstrumentation and over filling on retreated root canals. J Endod 1979;5:310-4. Bergenholtz G, Lekholm U, Milthon R, Heden G, 0desj0 B, Engstrom B. Retreatment of endodontic fillings. Scan J Dent Res 1979;87:217-24. Slavkin H. Does the mouth put the heart at risk? J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130:109-14. Debelian G, Olsen I, Tronstad L. Anaerobic bacteremia and fungemia in patients undergoing endodontic therapy: an overview. Ann Periodontol 1998;3:281-7.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43. 44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49. 50.

Reprint requests:

M-K Wu, MD, MSD, PhD Department of Cariology Endodontology Pedodontology Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA) Louwesweg 1 1066 EA Amsterdam, The Netherlands M.Wu@acta.nl

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Dental CodingDokument74 SeitenDental CodingSakshi Bishnoi100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Presented By: Dr. Sayak GuptaDokument47 SeitenPresented By: Dr. Sayak GuptaSayak GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020 Mcqs Dentin Pulp ComplexDokument13 Seiten2020 Mcqs Dentin Pulp Complexareej alblowi100% (1)

- Moh Exam Questions (10-7-18)Dokument9 SeitenMoh Exam Questions (10-7-18)Subhajit SahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Access Cavity Preparation An Anatomical and Clinical Perspective June 2011Dokument10 SeitenAccess Cavity Preparation An Anatomical and Clinical Perspective June 2011Eri Lupitasari100% (1)

- Esthetic Dentistry and Ceramic Restoration, 1edDokument331 SeitenEsthetic Dentistry and Ceramic Restoration, 1edMariana RaduNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 eNDODONTICS To PrintDokument19 Seiten1 eNDODONTICS To PrintDENTAL REVIEWER ONLYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cavity Classification and NomenclatureDokument23 SeitenCavity Classification and Nomenclatureyahya100% (3)

- Management of Deep Carious LesionsDokument5 SeitenManagement of Deep Carious LesionsEmeka V. ObiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Showpdf PDFDokument19 SeitenShowpdf PDFNay Oo KhantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biologic Effects of Dental MaterialsDokument13 SeitenBiologic Effects of Dental MaterialsendodoncistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Tentang Tes VitalitasDokument8 SeitenJurnal Tentang Tes Vitalitasmilton7777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Endodonta Test 2Dokument8 SeitenEndodonta Test 2Vijay K PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antibiotics As An Intracanal Medicament in EndodonticsDokument1 SeiteAntibiotics As An Intracanal Medicament in EndodonticsمعتزعليNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dental Caries As Focus of SepsisDokument77 SeitenDental Caries As Focus of SepsisnavdeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus DENT 336AAtmeh2Dokument9 SeitenSyllabus DENT 336AAtmeh2Firu LgsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Future of Laser Pediatric Dentistry PDFDokument5 SeitenFuture of Laser Pediatric Dentistry PDFsnehasthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Israeli State Exam For DentistryDokument75 SeitenIsraeli State Exam For Dentistryشبيبةالروم الملكيين الكاثوليكNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endodontic Failures-A Review: Dr. Sadashiv Daokar, DR - Anita.KalekarDokument6 SeitenEndodontic Failures-A Review: Dr. Sadashiv Daokar, DR - Anita.KalekarGunjan GargNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challenges in Dentin BondingDokument11 SeitenChallenges in Dentin BondingDanish SattarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labial Access For Lower TeethDokument3 SeitenLabial Access For Lower TeethHarish ChowdaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endodontic TT OutcomesDokument22 SeitenEndodontic TT OutcomesritikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stress Distribution in Molars Restored With Inlays or Onlays With or Without Endodontic Treatment: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element AnalysisDokument7 SeitenStress Distribution in Molars Restored With Inlays or Onlays With or Without Endodontic Treatment: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element AnalysismusaabsiddiquiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cold Testing Through Full-Coverage RestorationsDokument6 SeitenCold Testing Through Full-Coverage RestorationsSara Loureiro da LuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dental Caries: Signs and SymptomsDokument13 SeitenDental Caries: Signs and SymptomsGeorgiana IlincaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endo CrownsDokument19 SeitenEndo CrownsJyoti RahejaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulp TherapyDokument42 SeitenPulp TherapyruchikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Age Estimation by Pulp Tooth Area Ratio in Anterior Teeth Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Comparison of Four TeethDokument8 SeitenAge Estimation by Pulp Tooth Area Ratio in Anterior Teeth Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Comparison of Four TeethMeris JugadorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dental Anatomy: Đỗ Ngọc Thanh Trúc - 20RHM1Dokument9 SeitenDental Anatomy: Đỗ Ngọc Thanh Trúc - 20RHM1Dũng NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endoperiodontal Lesion: A Case ReportDokument3 SeitenEndoperiodontal Lesion: A Case ReportMarcelo MoyaNoch keine Bewertungen