Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

City Limits Magazine, October 1991 Issue

Hochgeladen von

City Limits (New York)Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

City Limits Magazine, October 1991 Issue

Hochgeladen von

City Limits (New York)Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

.

------------_

October 1991 New York's Community Affairs News Magazine $2.50

C H A R T E R R E V I S I O N W R A N G L I N G D Y O U T H I N C R O W N H E I G H T S

T H E N E W 1 0 - Y E A R H O U S I N G P L A N

City Limits

Volume XVI Number 8

City Limits is published ten times per year.

monthly except bi-monthly issues in June/

July and August/September. by the City Limits

Community Information Service, Inc .. a non-

profit organization devoted to disseminating

information concerning neighborhood

revitalization.

Sponsors

Association for Neighborhood and

Housing Development, Inc.

Community Service Society of New York

New York Urban Coalition

Pratt Institute Center for Community and

Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of Directors

Eddie Bautista. NYLPIICharter Rights

Project

Beverly Cheuvront. NYC Department of

Employment

Mary Martinez. Montefiore Hospital

Rebecca Reich. Turf Companies

Andrew Reicher. UHAB

Tom Robbins, Journalist

Jay Small, ANHD

Walter Stafford, New York University

Pete Williams. Center for Law and

Social Justice

Affiliations for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals and

community groups, $20/0ne Year, $30/Two

Years; for businesses, foundations , banks,

government agencies and libraries, $35/0ne

Year. $50/Two Years. Low income, unem-

ployed. $10/0ne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article

contributions. Please include a stamped, self-

addressed envelope for return manuscripts.

Material in City Limits does not necessarily

reflect the opinion ofthe sponsoring organiza-

tions. Send correspondence to: CITY LIMITS,

40 Prince St .. New York, NY 10012.

Second class postage paid

New York, NY 10001

City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)

(212) 925-9820

FAX (212) 966-3407

Editor: Lisa Glazer

Senior Editor: Andrew White

Contributing Editors: Mary Keefe,

Peter Marcuse. Margaret Mittelbach

Editorial Intern: Paula Kalakowski

Production: Chip Cliffe

Photographers: Andrew Lichtenstein,

Franklin Kearney

Copyright 1991. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be

reprinted without the express permission of

the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from

University Microfiims International,AnnArbor,

Ml46106.

2/0CTOBER 1991/CITY UMITS

Homeless Bashing

A

shamed and embarrassed. That's how a small but influential group

of city officials and journalists should be feeling for encouraging a

dangerous new trend-homeless bashing.

The most egregious example occurred in The New York Times,

where a front-page article by Celia Dugger depicted the shelter system as

a comfortable haven for lazy individuals angling for a city apartment.

There were no statistics backing up this claim, just one shocking

comment from Renita Steeley, a wife and mother of three who lives in the

Jackson Family Center in the Bronx. She said, "I consider this a little

vacation."

Maybe Celia Dugger should take a vacation for misquoting Steeley. In

a letter to the Times that was never printed, Steeley says she doesn't recall

the damning statement and adds, "The Jackson Family Center is no

vacation. Yes, we are grateful to have a roof over our heads, but we would

never have subjected ourselves to these conditions if we had the choice."

New York Magazine put a new twist on the homeless bashing trend in

their article, "Sue City." Author Peter Hellman never bothered to get out

of his office and interview anyone homeless-he just looked in his

rolodex and decided to blast homeless advocates like Bob Hayes and

Steven Banks for bankrupting the city.

When times are hard it's always tempting to look for an easy scapegoat.

Every homeless person isn't honest and litigation isn't the best way to set

social policy. But this is hardly the root cause of New York's problems.

Remember the recession? Rising unemployment? The ongoing crisis in

low-income housing? Just because these problems have been around for

a while doesn't mean they've gone away .

Sad to say, the new tone toward the homeless came from City Hall.

When the "Alternative Pathways" policy was announced last year, city

officials blamed the homeless for deluging the shelter system in the hopes

of finding a new apartment. As Steeley writes in her letter, "I had no

home, and I went to the city asking for shelter. If that's taking advantage

of the system, then what's the system for?"

* * *

Here's some news regarding City Limits. Close readers will recognize

a new byline this month-Andrew White has joined the magazine as

Senior Editor. A graduate of Columbia Journalism School, White has

freelanced for the Village Voice, the New York Observer and Metropolis.

Like community groups across New York, City Limits had a lean

summer. Many thanks are due to our enthusiastic summer interns-Anne

Sanger and Jodie Skillicorn-who helped keep the office running.

Finally, all of our readers are invited to the City Limits fundraising

party on Tuesday, October 15 at Two Boots Restaurant in Park Slope.

There will be live music, great food and autumn ambience, all for just $10.

If you can't make it out to Brooklyn, consider making a donation. Your

support is always welcome.

* * *

Correction: In last month's feature article, "A Synagogue Grows in

Brooklyn," we misidentified a Satmar leader. He was Grand Rebbe Joel

Teitelbaum. 0

Cover photograph by Ricky Aores

FEATURES

Disposable Dreams

The city trashes community recycling

Charter Revision: The Big Nothing?

Promises, promises. What became of them?

DEPARTMENTS

Editorial

12

16

Homeless Bashing .................................................... 3

Briefs

Market Makers .. ....................................................... 4

Banking Fight ........ .......... ......... ... ............. ... ....... ...... 4

Rent Reversal ........................................................... 4

Squatter Lawsuit ...................................................... 5

Profile

Where Credit Is Due ................................................. 6

Pipeline

Cosmetic Improvements ... ........... ... .... ..................... 8

Vital Statistics

Ten Year Housing Plan: The Update ...... .. ...... .... ... 20

Cityview

Passion and Pain .................................................... 22

Review

On The Outside Looking In ............................ ....... 23

Letters .... .............. ..... .... ..... .. ................... ... ..... ... ........ 24

Credit/Page 6

Trashed/Page 12

Charter/Page 16

CITY UMRS/OcrOBER 1991/3

MARKET MAKERS

After five years of inaction, a

developer is tinally moving

ahead with the revitalization of

La Marqueta, the dingy, rodent-

infested public market beneath

the Park Avenue viaduct in East

Harlem. But a large new retailer

is undercutting local merchants,

and William Del Toro's involve-

ment in the project is raising

neighborhoOd concern.

The developer, Constellation

Marketplace, is a subsidiary of

a midtown realty firm operating

under a lease from the Depart-

ment of Ports and Trade, which

is now part of the Department of

Business Services (DBS). Last

spring Constellation com"leted

the renovation of one of the

market buildings and Tops in

the Bronx, a large-scale dis-

count meat and grocery retailer,

moved in.

A few members of Commu-

nity Board 11 repart that Tops is

undercutting the prices of the

eight small vendors still present

in the market. Commissioner

Wallace Ford of DBS confirms

their charges. But Constellation

vice president Mark Ahasic says

that he is under no obligation to

protect the current vendors from

competition. He says the success

of the market depends on an

anchor store like Tops, and

arglJes that the increased foot

traffic Tops attracted this summer

only helped the small merchants.

Some neighborhood advo-

cates fear that the market's

redevelopment will spur

gentrification. "Several years

ago the community took a stand

on what we wanted," says Betsy

Colon, former chairperson of

Community Board 11. "It

wasn't just renovation. We

wanted a place for the small

vendors. They gave it away to

Tops in the Bronx."

La Marqueta has housed a

declining number of small mer-

chants since its heyday in the

1930s. The lease agreement

with Constellation includes

clauses that require the devel-

oper to I?rotect the small ven-

dors, to focus the Rroject toward

the development of an ethnic

marketplace, and to promote

jobs for local residents.

Commissioner Ford says his

staff contacted T <?ps and Con-

stellation in an effort to stop the

wholesaler from selling the

same products as the other

vendors. But, he adds, "I'm

convinced the introduction of

Tops has been helpful in terms

of stabilizing the market."

Del Toro is executive director

of the Hispanic Housing and

Economic Development Task

Force, a statewide, non-profit

Local Development Corparation

that is likely to become an offi -

cial fJOrtner in the La Marqueta

development, according to

Ahasic. He is a convicted felon

and has long been described by

community activists as a strong

supporter of gentrification.

Del T oro recently ran for City

Council and won the Demo-

cratic primary by 24 votes,

according to early returns. Ford

says that if Del T oro is the offi-

cial winner of the Council seat,

the new councilman will have to

recuse himself from any partici-

pation in the development work.

o Andrew White.

BANKING FIGHT

Community groups won a

tough fight this summer and

saved a crucial weapon against

discrimination by bonks.

Through letter-writing, phone

calling and steadyaavocacy,

they killed a banking lobby

attempt to weaken the power of

the Community Reinvestment

Act.

"It's gratifying how much

grass roots groups have

weighed into this fight. I think

they astounded members of

Congress," says Allen Fishbein,

general counsel for the Center

for Community Change in

Washington.

The proposed changes,

known as the Shelby-Mack bill,

would have weakened the

power of the Community Rein-

vestment Act (CRA), a law that

gives community groups the

ability to challenge discrimina-

tory bank lending "ractices. The

legislators intended to exempt

almost 90 percent of all banks

from the CRA challenge

process.

CRA was created in 1977 to

........

sa

sa

II.

...

NYC ......... '-IIJ C .. ..

.,

"

a

a

So

0 ... --

.PI , ..

4/0CTOBER 1991/CITY UMITS

( ......... ., .... )

counter "redlining," the bank

practice of denying loans and

services to low-income neigh-

barhoods-many of them Afri-

can-American and Latino. If a

community group has proof that

a bank discriminates, they can

use this information to challenge

the bank when it applies for

permission to expand its opera-

tions. Regulators can turn down

a bank's application as a result,

but this is usually avoided be-

cause the banks often negotiate

agreements to reinvest in the

community. More than 150

agreements have been negoti-

ated in 125 cities, pumping at

least $7.5 billion back into

communities, according to

studies.

Shelby-Mack would have

given a two-year "safe harbor"

exemption from any challenge

to banks receiving a favorable

reinvestment rating from regula-

tors. Fishbein estimates about

89 percent of banks get satis-

factory or higher ratings. It also

would have raised the threshold

above which banks must dis-

close lending data from $10

million in assets to $100 million.

Richard Wong, assistant

director of Asian Americans for

Equality, says the bill's defeat

showed that grassroots groups

can make their voices heard in

Washington. "Banking lobbyists

said this was something they

hadn't seen in a long time--on

outpouring of community action

on a bill in committee. It had the

effect of persuading representa-

tives to look more favorably on

the community aspect of the

legislation."

Fishbein notes that the fight

to save the CRA is not over. As

City Limits goes to press, the

Senate and House banking bills

are going to their respective

Aoors, and amendments similar

to Shelby-Mack could still be

introduced. Fishbein advises

community groups to remain

alert. 0 Judith Berek

RENT REVERSAL

Bronx tenants are being

forced to pay thousands ot

dollars in bock rent because the

state's housing department

reversed an earlier decision

f

..

granting rent abotements to the

tenants.

Four years ago, the tenants

of 3464 Knox Place in the

Norwood section of the Bronx

were granted a 7.5 percent

reduction in rent after inspectors

from the state's Department of

Housing and Community

Renewal found hot water

violations. The building's owner,

Gjerovica Associates, immedi-

ately appealed the decision,

saying that on the date of

inspection the boiler was being

cleaned, thereby explaining the

lack of hot water.

Calling the first decision

"erroneaus," DHCR ruled in

favor of the landlord this winter

and ordered tenants to pay

bock rent. Confused tenants

appealed the reversal but the

state agency decided this

summer to let the decision

stand.

"This whole thing, I think, is

very unfair to us. They gave it to

us ... and out of the clear blue

sky they tell us it was revoked,"

says Marian Ruiz a tenant who

now owes $1,359.44 in bock

rent. Ruiz, a single, unemployed

parent, explains that heat has

been consistently inadequate,

causing her to use space

heaters, seal her windows with

plastic and bring her 11-year-

old child into her bedroom to

sleep because his was so cold.

Claiming that this was an

ongoing, documented problem,

the tenants' association,

together with the Northwest

Bronx Community and Clergy

Coolition (NWBCCC), cited nine

New York City Department of

Housing Preservation and

Development (HPD) findings of

heat and hot water violations

over a three year period.

In their response to the

tenants' appeal, DHCR officials

stated, "In such cases, impartial

and corroborative evidence is of

great importance in determina-

tion of the issues. The only

corroboration in the record to

support the allegations are HPD

violations covering a four year

period .. . The Commissioner is of

the <?pinion that there is

insufticient independent proof to

sustain the allegation of a

building-wide dimunition of

. "

services.

Assistant Commissioner

Joseph A. D' Agosta explains

Face-to-face: Tenants in buildings owned by Finklestein-Morgan protested recently at the Westchester home

of Steven Finklestein (at right). They said the landlord repeatedly failed to make basic repairs. The protest

was orgamzed by the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition.

that while the case was under

investigation, DHCR inspectors

found adequate heat and hot

water on several 1990-1991

visits to the apartment building.

Based on this information, he

says, the decision was reversed.

Helen Schaub, a NWBCCC

organizer, argues that while the

heat problem might now be

solved, this does not erase three

frigid winters or justify demand-

ing four years of bock rent. 0

Tracey Tully

SQUAnER LAWSUIT

About 500 squatters in city-

owned apartment buildings are

being saved from eviction, at

least for the time being, as the

result of a recent order issued

by the appellate division of New

York Supreme Court.

The order comes on the heels

of a lower court ruling that said

squatters must be informed,

before they are evicted, of a city

policy that could allow some of

them to receive legitimate

leases.

Justice John Carro de-

manded that the Department of

Housing Preservation and De-

velopment delay evicting the

squatters while government

lawyers appeal to reverse the

lower court ruling. The squatters

are secure in their apartments at

least until the next court date in

December.

The original lawsuit in the

lower court was brought by the

Legal Aid Society against the

Department of Housing Preser-

vation and Development. Legal

Aid is representing squatters in

city-owned buildings in Brook-

lyn, Manhattan and the Bronx.

At issue is HPD's three-year-

old Unauthorized Occupant

Policy, which outlines how ille-

gal tenants in in-rem buildings

should be evaluated and, in

deserving cases, offered leases

by city property managers.

Legal Aid and the squatters

contend that they were never

told about the policy.

But Daniel T urbow, the city

lawyer representing HPD, says

the policy was only applicable

to squatters occupying city

apartments before April 1,

1988, or those coming after

who had special circumstances,

such as family members of a

former tenant, occupants with

children, pregnant women or

persons with a permanent dis-

ability. These qualifications are

not mentioned in a 1988 HPD

memo outlining the policy to city

property managers.

Marshall Green, attorney for

the squatters, says that the

policy was applied arbitrarily

and secretively from the very

beginning. "I think on one hand

[HPD) wanted a policy, but on

the other hand they wanted to

keep it a secret," he says. ''The

court found that it's inconsistent

with due process to have a

secret process."

Michael Kink, another Legal

Aid attorney, says that many

occupants learned of the policy

for the first time when they were

in court protesting eviction

notices. T urbow says the city

attempted to notify the squatters,

but they did not answer their

doors when managers knocked.

Tom Gogan, a coordinator

for the Union of City Tenants,

questions the efforts made by

building managers. "Unfortu-

nately, not all the HPD manag-

ers themselves are on the

up-and-up," he says, adding

that all the tenants of a building

should be consulted in the deter-

mination of who should be

offered leases, rather than

letting a city employee make an

arbitrary decision.

Advocates note that although

some squatters - particularly

drug dealers - are unwelcome

in city-owned buildings, others

move in with the approval of

active tenant associations and

spend their own money fixing

up their apartments for their

families.

Meanwhile, the city is re-

viewing the Unauthorized Occu-

pant Policy. Depending on the

outcome of the lawsuit, Turbow

says it may be modified or

completely eliminated. 0

Bonnie PfIster

CITY UMITS/OCTOBER 1991/5

By Abby Scher

Where Credit is Due

Economic empowerment in Central Brooklyn.

F

inding a bank in a six-mile slice

of Central Brooklyn is to embark

on an odyssey. I took such a trip

in a modern-day Argus, a dark

blue Hyundai driven with alarming

speed and (some) skill by Errol T.

Louis. Most ofthe banks we encoun-

tered were shuttered graffiti-laden

shells. Their entry ways sometimes

served as shelter to men drinking beer.

One had been converted into a dis-

count store.

Louis and his political twin, Mark

Griffith, are on a mission to transform

the bleak bankless landscape of Bed-

Stuy and Crown Heights with a com-

munity-run credit union and a

revolving loan fund that will provide

much-needed financing for their

neighborhoods.

While their goal of economic em-

powerment may seem far-fetched in

the face of chronic redlining by banks,

government budget cuts and a rising

unemployment rate, the hard work

and political experience of these

young men are turning a pipe dream

into reality. They hope to open the

credit union by December, and the

Urban Development Corporation is

disbursing $200,000 for a revolving

loan fund to be run jointly by three

community groups, including Louis'

and Griffith's base of operations, the

Central Brooklyn Partnership for Eco-

nomic Development. The Central

Brooklyn Partnership is a loosely-

affiliated alliance of 10 groups, in-

cluding the Prospect Heights

Neighborhood Corp. and the Park-

way-Stuyvesant Community and

Housing Council, which is organizing

the credit union and bank advocacy

efforts.

Even though Griffith and Louis are

only in their late 20s, they have a

well-formed vision for their commu-

nity. They share a commitment to

community-run financial institutions

that are not subject to the whim of

powerful political figures, funding

cuts or the continuing drain of local

deposits into the coffers of big banks.

They also want to nurture economic

self-help within the African-Ameri-

can community as a way to generate

jobs, healthy businesses and adequate

housing.

a/OCTOBER 1991/CITY UMITS

Saving Jobs and Homes

"You can save a person's job, save

their family and their home just by

making a loan," says Louis. "If we

acquire a building and get the credit

union charter, we'll help stabilize a

lot of the damage being done to the

community by the downturn in the

economy."

The money men: Errol Louis and Mark Griffith.

They have found some enthusias-

tic allies. On a recent visit to St. Gre-

gory the Great Roman Catholic Church

on Brooklyn Avenue, their sales pitch

spurred about 80 parishioners to join

more than 500 other Central Brooklyn

residents in pledging to deposit money

into the credit union organized by the

Central Brooklyn Partnership. A num-

ber of St. Gregory parishioners also

intend to join the operation of the

institution.

"A credit union would be helpful

for our community because it would

be readily accessible for people with-

out large amounts of money to get

loans," says Milton Lovell, a parishio-

ner who owns a brownstone in the

neighborhood. "My experience with

banks is that you have to prove to

them that you don't need a loan before

you get one. I think a credit union

would be somewhat different."

Beyond 500 Pledges

Some of the hundreds who made

pledges have never held bank accounts

and regularly spend $1.25 on money

orders to pay bills. Others have saved

in Caribbean-style sou sous, which

carry some risk and offer no interest.

These commitments put the organiz-

ing effort well into its first phase.

During the review of charter applica-

tions for a federally-insured credit

union the National Credit Union Ad-

ministration evaluates the depth of

community support, and 500 pledges

is usually the benchmark number.

Two recent events have pushed up

the pace and increased the chances

for success. The bankruptcy of the

Harlem -based Freedom National Bank

and the shutdown of its Nostrand

Avenue branch last winter sparked

enormous anger within the neighbor-

hood about the community's failure

to control the financial institutions in

its midst. Helping to direct that anger

was a $2,000 seed grant from the North

Star Foundation to the Central Brook-

lyn Partnership, which paid for a

summer intern who organized the

pledge drive for the credit union. The

intern arranged information sessions

about the loan fund and credit union

with local merchant associations,

churches, a hospital and day care cen-

ter staff.

Emotional Infrastructure

The obvious affection Louis and

Griffith hold for one another provides

the little-seen emotional infrastruc-

You can save a

person's home by

making a loan.

ture underlying the endeavor. Their

friendship has sustained the Central

Brooklyn Partnership in the three

years since the credit union idea was

first floated by the director of the

Crown Heights Neighborhood Im-

provement Association, where Griffith

used to work.

Their backgrounds are remarkably

similar; it's as though the men were

identical political twins separated at

birth and reunited by some twist of

fate. Both are sons of civil servants in

Caribbean-American families with

roots in the area. Griffith lived his

early years in Bed-Stuy before mov-

ing to Queens, and then back again

after college. Louis, who grew up in

New Rochelle, moved to Crown

Heights to be a live-in repairman at a

brownstone his aunt purchased in the

1950s. Both cut their political teeth

organizing South Africa divestment

campaigns at Ivy League universities

-Griffith at Brown and Louis at

Harvard. Freelance writing is a side-

line for them both and readers may

recognize them as occasional contribu-

tors to City Limits.

They also share a congenial opti-

mism. Phrases like "relentlessly en-

ergetic" come to mind. "They don't

seem to grow weary. They always

seem on the upbeat," says Kenneth

Gulley, an ally who runs the Mid-

Brooklyn Community Economic De-

velopment Corporation.

Clifford Rosenthal, the executive

director of the National Federation of

Community Development Credit

Unions, where Louis is a program

officer, suggests that Louis sustains

his remarkable organizing energy be-

cause he has the "blend of idealism

and pragmatism" that is needed to

survive doing public service work in

New York City. That pragmatism is

reflected in the organizers' matter-of-

fact pitch to bankers: they ask politely

for money to support the Partnership's

initiatives while waving documenta-

tion of the bank's racist redlining.

Louis and Griffith's full-time work

schedules and 40-hour volunteer

weeks mean that they often hold strat-

egy sessions for the Partnership over

dinner at inexpensive restaurants,

since neither has time to cook meals.

Griffith will soon leave his job as a

paid political organizer at the Com-

munity Service Society to work full-

time running the Revolving Loan Fund

and Partnership operations-hope-

fully for a salary. Louis is switching to

part-time hours at the National Fed-

eration of Community Development

Credit Unions to attend to the Partner-

ship and his Ph.D studies in political

science at Yale University.

With more time devoted to the

credit union, Louis and Griffith hope

to develop an active and committed

volunteer base. They want to draw

supporters from the different segments

of the community-working class

homeowners who need renovation

loans, owners of small businesses who

require extra money to tide them

through the recession, homeless

people who have no place else to set

up a bank account.

Referring to the nascent project,

Griffith says, "We're at a critical point

right now. Community empowerment

doesn't mean anything unless people

really take ownership ofit." 0

Abby Scher is a freelance writer who

specializes in banking issues.

Advertise

In

Ci ty Limi t8!

Call

925-9820

Competitively Priced Insurance

We have been providing low-cost insurance programs

and quality service for HDFCs, TENANTS,

COMMUNITY MANAGEMENT and other NONPROFIT

organizations for over a decade.

Our Coverages Include:

FIRE LIABILITY BONDS

DIRECTORS' & OFFICERS' LIABILITY

SPECIAL BUILDING PACKAGES

ilLiberal Payment T erms"

PSFS,INCo

(FORMERLY POHANI ASSOCIATES)

LET US DO A FREE EVALUATION OF

YOUR INSURANCE NEEDS

306 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10001

(212) 279-8300 Ask for: Bala Ramanathan

CITY UMITS/OCTOBER 1991/7

By Chris Yurko

Cosmetic Improvements

Shelter families get renovated city-owned

apartments-in decrepit buildings.

R

osemary Roldan smiles as she

sweeps the black and white li-

noleum floor of her new apart-

ment. She has a brand new stove

and refrigerator in the kitchen, spar-

kling new fixtures

in the bathroom,

recently painted

walls and ceil-

ings. She loves

her new home,

she says. But the

picture is not per-

fect.

known as "Alternative Pathways,"

apartments in completely renovated

city buildings are now set aside for

families living doubled-up with rela-

tives and friends. This means that

Spiller, deputy commissioner of

HPD's Office of Property Management.

The repair agency is also responsible

for connecting prospective homeless

tenants with the renovated apart-

ments, and for the administrative de-

tails that follow. Thirty days after a

family moves in, they become tenants

of HPD's Division of Property Man-

agement (DPM).

During the late 1980s, BV ARR be-

came a target of criticism by advo-

cates for the homeless because of sub-

standard and in-

complete repair

work, and in 1988

the city comp-

troller's office

blasted the bu-

reau for shoddy

renovation and a

total lack of coor-

dination between

the different com-

ponents of build-

ing repair. Since

then, Spiller says

BVARR has

cleaned up its act.

Advocates agree

that newly re-

paired apart-

~ ments are much

~ better than they

~ were a few years

If) ago.

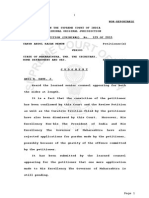

When Roldan

moved into her

apartment last

December, the

new linoleum

floor was already

cracked. After six

months, the new

paint job was

scarred by water

stains carving a

path down a kit-

chen wall to an

electrical outlet

above the coun-

ter. And plaster is

now dangling

from a 'yellow-

Water ways: Leaks are ruining the ceilings and walls in Rosema.ry Roldan's BV ARR apartment.

But the criticism

hasn't ceased.

"Our cry has been

edged hole in the living room ceiling.

What's the cause of these prob-

lems? The rest of the city-owned build-

ing is in lousy shape. Leaks in pipes

above Roldan's rooms are slowly ru-

ining the ceilings and walls. And in

the hallways and stairwells, the wind

and unwelcome visitors enter through

broken windows and the doorless front

hall. Drug dealers operate out of a

neighbor's apartment. Still, the 30-

year-old single mother of four prefers

the conditions of her new residence at

440 East 139th Street in the South

Bronx to those of the welfare hotel on

Crotona Park North where she used to

live.

Her apartment is one of 1,648 pre-

viously vacant units renovated in the

past fiscal year by the Bureau of Va-

cant Apartment Repair and Rental

(BV ARR), a sub-section of the city's

housing department that dwarfs all

others in housing for the homeless.

Because of a recent city policy

a/OCTOBER 1991/CITY UMITS

BVARR apartments are virtually the

only source of permanent housing for

families from the shelter system. Ad-

vocates say that while the quality of

the apartments has improved in re-

cent years, enormous problems per-

sist because of the severe decrepitude

of most city-owned buildings.

Creation of BV ARR

The Koch administration created

BV ARR in 1983 after policymakers

announced that all vacant apartments

in occupied city-owned buildings

would be renovated for the homeless.

Since then, BV ARR has produced

14,857 of the 25,222 apartments cre-

ated for homeless families by the de-

partment of Housing Preservation and

Development. At a cost of $27,000,

each unit receives new appliances,

new wiring, new fixtures, new

sheetrock, new tiling in the bathroom,

new linoleum on the floors and a fresh

coat of paint, according to William

that you can't

spend money on the vacant apart-

ments and not touch the rest of the

building," says Rose Anello, coordi-

nator of the Emergency Alliance for

Homeless Families. Tom Gogan, a

coordinator at the Union of City Ten-

ants (UCT) , agrees. "You often get

people moving in and saying the re-

pairs were just a cosmetic job," he

says. "The walls and ceilings were

fixed, but the [building's] plumbing

never got done. That's the most com-

mon problem. You have a situation

where the basic systems are not dealt

with."

Spiller says BV ARR does have a

responsibility to repair adjacent apart-

ments if problems are affecting work

in BV ARR units. He says the repair

team will not renovate any apartment

if there are severe structural problems

in the building.

But Anello notes that almost all the

3,300 buildings managed by HPD's

Division of Property Management are

in such bad shape that only building-

wide rehabilitation can solve the prob-

lems BV ARR tenants face. " If any-

thing these are the buildings that need

the most intense advocacy, " she says,

arguing that the city should stop wast-

ing resources on superficial repairs

and spend more money on fixing struc-

tural problems like faulty plumbing,

wiring, and crumbling ceilings and

floors.

A study prepared by the Commu-

nity Service Society, set for release

this month, reports that 82 percent of

the 375 apartments surveyed in East

Harlem's DPM-managed buildings

"These are the

buildings that need

the most intense

advocacy. "

have one or more serious rroblems.

According to Luis Sierra 0 CSS, the

problems counted were: no heat or

hot water, severe cracks and holes in

walls and ceilings, exposed wiring,

and sagging and rotting floors.

Budget Cuts

Despite these problems, major bud-

get cuts at the city's housing depart-

mentmean that homeless families who

move into BV ARR apartments, and

become tenants of DPM, may have to

wait a long time before they receive

any kind of repairs.

Spiller says there is a backlog of

86,000 repair orders within central

management. And according to the

housing department, each building

manager is responsible for 330 apart-

ments this year, up from 250, because

of a hiring freeze.

Another city effort, the Capital Im-

provement Program, fixes structural

problems in buildings and renovates

occupied apartments, but that pro-

gram was cut by more than 37 per-

cent, or $14 million, this fiscal year.

Within the BVARR unit, 27 staff

members have been lost through attri-

tion and future renovations will con-

sist of more repairs to existing fixtures

and less replacement. Spiller notes

that some of this year's 1,648 BV ARR

units will be transferred to the Capital

Improvement Program for more ex-

tensive work, but is unable to specify

how many apartments this policy shift

will affect.

Class System

Besides the repair problems ,

BV ARR also comes under fire for cre-

ating a virtual class system among

tenants in city-owned buildings. Ten-

ants of Roldan's building fought for

years to get basic repairs done on their

broken walls, tumbling ceilings and

leaking pipes. Last year, some of the

occupied apartments were fixed, some

weren't. Meanwhile, BV ARR painted

the walls and installed new fixtures

in what later became Roldan's new

home.

SUPPORT SERVICES FOR NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

Writing 0 Reports 0 Proposals 0 Newsletters 0 Manuals 0 Program

Description and Justification 0 Procedures 0 Training Materials

Research and Evaluation 0 Needs Assessment 0 Project Monitoring and

Documentation 0 Census/Demographics 0 Project and Performance

Evaluation

Planning and Development 0 Projects and Organizations 0 Budgets

o Management 0 Procedures and Systems

Call or write Sue Fox

710 WEST END AVENUE

NEW YORK, N.Y. 10025

(212) 222-9946

Nonprofit Facilities Fund

10 Years of Service to the Not-For-Profit Community

Loans for Capital Projects

Capital Improvement Planning

Energy and Preventive Maintenance Consulting

contact: Jeanne Vass or Liza Paschal

Nonprofit Facilities Fund

12 West 31st Street/2nd Floor

New York, New York 10001

Tel: (212) 868-6710

CITY UMnS/ OCTOBER 1991/9

Roldan says many of her neighbors

resent that she has such a nice apart-

ment. "Everybody says I have the

cleanest apartment in the whole build-

ing," she comments. "Everybody got

upset, but it wasn't my fault."

For 12 years the Rivera family has

lived in a fifth floor apartment in the

same building. Luis Rivera, 32, says

he has been complaining to central

management for seven months about

a stove that doesn't work. Meanwhile,

the family has been using a portable

propane stove to cook. "Propane is

very dangerous, but what else can we

do?" asks Rivera. "The people that

live here the longest have the worst

apartments. It's not fair."

These problems are repeated across

the city. Bernard Alston, an organizer

at UCT, says that in another Bronx

building where BV ARR is currently

renovating a top floor apartment with

"brand new circuit breakers, gates on

windows, stuff other tenants can't get,"

another tenant downstairs has had a

Pension Plans

All types of Plans and Benefits

Contributory and Non-Contributory Qualified and Non-Qualified

Free consultation Free evaluation of your present plans

Health and Life Insurance Employee Savings Plans

Go with MetLife the leader in Pensions, Benefits, and Life Insurance with

top ratings from A.M. Best, Standard and Poors, and other rating services.

So find out why more Non-Profits are saying ...

"Get Met. It Pays"

Larry Hochwald (718) 287-4731 MetLife

15 Bay Ridge Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y. 11220

!I

broken sink lying on the floor of her

bathroom for two and a half years. She

has gone to court, gotten repair orders

from the judge, withheld rent, and

still the sink hasn't been fixed. Now

HPD is taking her to court for non-

payment of rent.

"Generally, [BV ARR] does create

some resentment," concedes Spiller.

"It would make more sense if we could

be relieved of BV ARR. If we could do

capital improvements in all buildings

it would improve everybody's life.

But that would mean fewer apart-

ments for people in the shelter sys-

tem. [Capital improvements] take one

year, BV ARR takes two months."

In a time of limited resources, city

agencies can only pursue limited

goals, and true improvements to city-

owned buildings are getting further

out of reach these days. As Anello

sees it, community advocates will have

to stand tough to prevent the quality

of both BV ARR and central manage-

ment apartments from collapsing. She

isn't confident. Without strident

advocacy, she says, "it's pretty clear

there will be another downward

spiral." D

Chris Yurko is a freelance writer based

in New York City.

Bankers Trust Company

Community Development Group

A resource for the non .... profit

development community

Gary Hattem,Vice President

280 Park Avenue, 19West New York, New York 10017

Tel:212,850,3487 FAX:212,850,2380

10/0CTOBER 1991/CITY UMITS

'.

Blueprint

For Change

Case in Point: h _ ..-.

Fulton Landing---

Incubator Project

The NY/NJ Minority Purchasing Council

has a dream: create an incubator for

small business minority entrepreneurs.

The incubator itself is a four-story water-

front building in the Fulton Landing

area of downtown Brooklyn. When

completed, it will offer shared office

services, managerial and technical

assistance, and below market rents.

Citibank, through its Citibuilders Pro-

gram, is financing $220,000 of the nearly

$310,000 needed for the first phase

of this project. The Minority Purchasing

Council is providing the rest. They asked

if Brooklyn Union's Area Development

Fund could help with a one-year work-

ing capital loan of $50,000.

We could and we did. We've found

that our Area Development Fund is a

working blueprint for change in the

economic and social life of New York. If

your company would like to help as has

Citibank, Pfizer, Bankers Trust Company

and so many others, talk to Jan Childress

at (718) 403-2583. You'll find him

working for a stronger New York at

Brooklyn Union Gas ... naturally.

Union Gas,

Naturally .S. >i=

Ar_ Fund

CITY UMrrs/OCTOBER 1991/11

Disposable Dreams

Budget cuts may kill community-based recycling.

BY ANDREW WHITE

s the heat settled on Brooklyn this summer, Lorraine

A

Floyd and John Cousar of All Boro Recycling had

to make radical changes to their business plan.

They lost government contracts. Their main source

of income fell victim to the recession. Suddenly,

their business had no clear future.

Cousar and Floyd employ five men and women from

the streets of Central Brooklyn. The team sorts, transports

and sells recyclable garbage, including plastics, card-

board, newspaper, glass, steel, brass, copper and alumi-

nium. Their three trucks carry most of the materials

collected by community recycling drop-off centers in

three boroughs to a community-run buy-back, processing

and marketing center in the South Bronx.

For years, All Boro made money selling recyclable

material to the processing center, known as R2B2. More

recently, they helped sustain voluntary recycling centers

in neighborhoods like Prospect Heights, Marine Park,

Nottingham and Canarsie because they offered their truck-

ing services for free. In some cases, they even gave some of

their profits back to community groups. Not any more.

All Boro, R2B2 and more than a dozen voluntary drop-

off centers across the city are part of a fledgling commu-

nity recycling network that provides a panoply of economic

and environmental benefits. The organizations save the

city money by reducing the flow of garbage to the nearly-

12/0CTOBER 1991/CITY UMITS

full Fresh Kills landfill. They offer jobs for unskilled

workers in need of steady income. And they give practical

recycling experience to residents of neighborhoods across

the city.

In the wake of draconian budget cuts, this network is

now facing extinction. The Department of Sanitation's

recycling funds for the current fiscal year have been

slashed from $65.5 million to $11.4 million and all outside

contracts with community-based groups have been elimi-

nated.

Representatives from more than a dozen groups came

together recently to create the Community Recycling Al-

liance. They're determined to fight back and organize so

that community recycling can be saved-and eventually

expanded. "Never underestimate the resilience or re-

sourcefulness of committed individuals and community

based organizations in the face of hardship," says David

Muchnick, chairman of the board ofR2B2.

"Someday community recycling centers will be allover

the place," adds Karen Gleeson, a long-time recycling

activist and organizer of the Prospect Heights drop-off

center in Brooklyn. "We're creating a dream we all have.

We're doing something for the city."

Curbside Focus

When New York City started its recycling program two

years ago, community-based efforts were only one small

part of the plan. The bulk of the funding was directed

towards curbside recy-

cling, managed and

operated by the Sani-

tation Department.

That program has not

been a success; less

than six percent of the

city's waste stream is

now collected for re-

cycling.

Drastic cuts

R2B2, which stands

for Recoverable Re-

sources/Boro Bronx

2000, is the under-

pinning of the entire

community recycling

network. A nonprofit

community organi-

zation, R2B2 pays com-

munity groups for the

trash they pickup, then

processes it into bales

of raw material that are

sold to manufacturers

and distributors

around the country.

City and state laws

mandate, respectively,

25 percent recycling by

1994 and 42 percent

by 1997. Environmen-

talists charge that the

city undermined its

own effort by failing to

educate residents

about the program on

Uncertain future: R2B2's buy-back operation may have to close.

But the loss of city

contracts and the re-

the streets and in the neighborhoods. Even the most

committed activists agree that a curbside program must

playa role in the city's recycling future. But they say

neighborhood groups are the most obvious and cost-

efficient method of spreading the word.

"Ithey had started at the community level and worked

up, using the kind of cash they had, we would have had an

enormously successful project by now," says Nancy Wolf,

executi ve director of the Environmental Action Coalition.

Instead, the government set up its own disorganized

outreach program, and the neighborhood groups won just

a few small grants of government support.

Meanwhile, officials at the sanitation department say

that recycling just doesn't work very well in New York.

They point to low success rates for the curbside program

in low-income neighborhoods. Activists react with vehe-

mence. "We said over and over again, do not go into low-

income neighborhoods with this, but they ignored us,"

Wolf says. "We said don't do curbside. Educate in the

schools and through the community-based organizations.

Send mobile buy-backs to the housing projects. After the

people understand, that's when you start curbside recy-

cling. That's several years down the road."

Today, even the curbside program is in jeopardy. The

administration decided to fund the program until Decem-

ber 1, when all funds are scheduled to run out. At that

time, the department plans to set the program in mothballs

until at least next July 1. Meanwhile, the city is rapidly

moving forward with plans to pursue incineration as New

York's primary waste disposal strategy for the 21st cen-

tury. (See sidebar.)

Members of community recycling groups say the bud-

get cuts reveal New York City's minimal commitment to

recycling. They see policy makers pushing forward with

the incineration plan and intentionally fumbling the recy-

cling option. "Everywhere else, recycling is being devel-

oped, markets are being developed," says Carl Hultberg,

an organizer for the Village Green Recycling Team in

Greenwich Village. "Here it's just a charade."

City officials confirm that community-based recycling

organizations are an expendable accoutrement in the

city's garbage disposal plans. They're "worth funding

when you have the option," says DOS spokesperson Anne

Canty, but they are "not the type of service an agency like

this is mandated to provide."

cession in the manu-

facturing and construction industries, where most

recyclables end up, has undermined R2B2. This summer,

the company had to cut back the staff and hours of

operation dedicated to buying materials from the commu-

nity groups. What's worse, the plant has stopped paying

for everything except aluminium cans and newspaper,

and only buys plastic by the truckload. And they pay just

a fraction of the price they were worth six months ago.

That means All Boro and other truckers have lost their

main source of income.

David Muchnick from R2B2 says he isn't sure the

company will be able to continue accepting anything but

plastics after the next few months. Asked if he is confident

that he can continue the buy-back operation that sustains

All Boro Recycling and the drop-off centers throughout

the city, he responds with gloom in his voice. "I'm not

confident. But we will do our damndest."

Yet the future remains clear for recycling. World mar-

kets for the materials are growing steadily, particularly in

the far east and in Eastern Europe, says Jerry Powell of

Resource Recycling magazine. And intensive recycling

has been shown to be an effective method of waste man-

agement. Newark, New Jersey, now collects between 45

and 55 percent of its waste for recycling. Seattle has done

equally well. And New York has an advantage over most

other cities: the Port of New York and New Jersey sends

out a huge proportion of the world's recyclable materials,

collected from much of the eastern United States.

Despite this growing market, the impending closure of

Fresh Kills landfill and the increasingly exorbitant cost of

alternatives, like trucking garbage to the Midwest, city

support for recycling is rapidly diminishing. As Hultberg

says, "Before long, we'll be back to where we were 10 years

ago when there was only one recycling center in the city."

Closing Doors

Last spring, the outlook for community recycling wasn't

nearly as bleak. The Brooklyn Recycling Center (BRC), a

buy-back and processing plant funded by the city and

operated by R2B2 and Brooklyn Ecumenical Coopera-

tives, opened on the Sunset Park waterfront. Ten new

neighborhood drop-off centers sprouted in Brooklyn. Small

groups started carrying materials to the center in vans and

cars, earning a little cash. It was the birth of a movement.

In Kensington, seven men and women got together and

CITY UMnS/OCTOBER 1991/13

Burning Money

Sanitation Commissioner Steven Polan's recent

announcement that the city plans to build three new

incinerators confirms the Dinkins administration's

commitment to burning garbage instead of recycling

it. Review of recent budget figures reveals the huge

cost of this commitment.

Cost estimates for the three new incinerators have

not yet been released, but the city has already pledged

hundreds of millions of dollars to renovating exist-

ing incinerators.

According to the administration's capital plan for

the years 1991 to 1995, more than $283 million is

allotted to pollution control and "other improve-

ments" at the 33-year-old Greenpoint incinerator,

the 42-year-old waste-to-energy plant in Woodside

and the 31-year-old Southwest Brooklyn incinera-

tor . And another $559 million has been

reappropriated from last year's capital budget plan

for the construction of a new incinerator at the

Brooklyn Navy Yard in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

"If they took a fraction of what they're putting into

incineration and put it toward recycling, we could

have thoroughly effective systems lasting many

years," says Alisa Culver of the Park Slope Recycling

Campaign, an outreach program of Barry Commoner's

Center for the Biology of Natural Systems. "It's crazy

that the city put even a penny into trying to fix the

incinerators from the 1960s," she says. "I wouldn't

put a cent into a car I bought in the 1960s."

Culver and other environmentalists argue that the

city can't sustain an effective recycling program

while funnelling cash into incinerators. To remain

economically viable, they say, incinerators must

burn trash at a near-capacity pace every day of their

lives. That means the city will have to limit the

amount of recyclable materials removed from the

waste stream, because most of the trash that is recy-

clable is also burnable. "Most communities that are

doing very well with recycling have abandoned

spending on incinerators," Culver says. Seattle, for

instance, abandoned its incineration plan in 1987,

diverted most budget resources towards recycling,

and currently recycles about 45 percent of its waste

stream. The city plans to reach 60 percent within a

few years.

Incinerators can only consume 70 percent of the

waste volume fed into their furnaces, and the ash

that remains has to be disposed of as landfill. Environ-

mentalists estimate that intensive recycling programs

can dispose of between 60 and 75 percent of the

waste stream.

But the Dinkins administration has shown little

faith in recycling as an effective alternative for waste

management. "There are many communities in the

city that would never achieve" 60 percent recycling,

says sanitation department spokesperson Anne

Canty. "Some individuals might, but whole commu-

nities never will." Cynically, the city government

believes New Yorkers prefer to breathe their waste

rather than make the effort to recycle it. Andrew

White

14/0CTOBER 1991/CITY UMITS

started a Sunday collection of recyclables, carrying the

material to the Brooklyn buy-back center and turning the

earnings over to the 70th Precinct Youth Council. The

concept was spreading beyond these budding groups

when the cudgel fell. On July 31, the city withdrew BRC's

contract, and the center closed.

The city hasn't reimbursed BEC or R2B2 for the money

they funneled into the ill-fated buy-back, says David

Hurd, recycling operations specialist at Bronx 2000. "We

spent months and months developing business plans,

finding a site, renovating the building, then they revoked

the funding. They left us holding the bag." He says the city

is still obliged by contract to cover the costs, but the budget

crisis has frozen the payment process for the time being.

Last year, on the other side of Brooklyn, the East New

York Urban Youth Corps started collecting glass, metal

and cardboard from many of the 64 companies based in

the East New York Industrial Park. Teenagers ran the

business and kept track of finances with the help of Carey

Shea, the corps' executive director. They collected, sorted

and packaged the materials and loaded them on All-Boro' s

trucks. All Boro sold the loads to R2B2, and passed the

proceeds on to the youth group. But once the city dropped

All Boro's contracts, the company could no longer afford

to give the corps any cash for the truckloads. "Our project

became a real money loser," says Shea. In mid-August, the

program that employed 20 young men and teenagers

crumbled as its funds disappeared.

On the Lower East Side in Manhattan, Outstanding

Renewal Enterprises has two recycling drop-off points

and a new ecology center on East Seventh Street between

avenues B and C. The group collects and processes about

10 tons of recyclable goods each month. At the Seventh

Street site, income from the sale of recyclables to R2B2,

compost made from kitchen waste collected from neigh-

borhood residents, and the hard work of volunteers com-

bined to transform a rubble-strewn lot into an urban green

space. It's a physical manifestation of the web that binds

recycling to the environment, says Christina Datz, the

creator of the project. She says the work has taught local

people the value of their so-called "garbage."

But the greening of Loisaida isn't free, and the crisis

may kill Datz' program. "It's come to a brutal halt," she

says. "We have no money for fuel, no money for truck

maintenance, no money for educating children. I'm giving

myself until December. Ifwe don't get funding we have to

close. This is just overwhelming."

Innovate to Survive

The crisis blind-sided All Boro as well. Last fall, Floyd

and Cousar quit their full time jobs at Rochdale Village in

Queens, where Cousar was head of security and Floyd was

executive secretary, to devote themselves fully to their 12-

year-old business.

"We had dollars saved," says Floyd. "Prices for materi-

als were up high. The city was opening up the new plant

in Brooklyn. We was making out." Then the city dropped

about $19,000 worth of contracts with the company, says

Cousar, and the Brooklyn buy-back center closed. As of

August, Floyd says, the pair's savings accounts were just

about exhausted.

But All Boro found new ways to make money. They

clean abandoned lots and salvage appliances for resale.

They hire out their trucks as moving vans. And in mid-

August All Boro opened the front gate of a cluttered

,

~

storage lot near the corner of Classon and Lexington

avenues in Clinton Hill, set up a table and started trading

a nickle for every two deposit bottles and cans that

neighborhood resident turned in. Word spread quickly.

Block associations, senior citizens and homeless men

from the Atlantic Avenue shelter a few blocks away came

to All Boro to avoid the harassment they experience at

local supermarkets. All Boro makes a profit by redeeming

the bottles and cans for full value at a We Can redemption

center in Manhattan. Floyd says she paid out $266 to local

people at Classon A venue in one day during the second

week of operations. "This is just a way to survive," she

says.

But Cousar isn't entirely confident. If R2B2 closes its

buy-back operation, he says, "we would probably go

under shortly after that."

Economic Development

All Boro, R2B2 and the other community recycling

operations do more than just process trash. They also

harness the intrinsic value of recyclable material for

economic development.

In the South Bronx, R2B2 employs 20 local workers and

helps neighborhood businesses reduce their waste disposal

costs and add income through selling recyclables. David

Hurd from Bronx 2000, estimates that R2B2 has created $2

million worth of economic benefits for the immediate

community. "These are jobs for unskilled labor," says

Gleeson of the Prospect Heights center. "They're the kind

of jobs we're losing rapidly. It's the low end of the economic

spectrum."

The possibilities for job creation and industrial devel-

opment based on recycling in New York are far from

negligible. The city's curbside program is run in a way that

creates a dirty mix of recyclable materials that is difficult

to sort. A better approach, using the methods of commu-

nity groups as a model, can generate a valuable stream of

high-quality recyclable goods that can be sold for top

dollar. Muchnick of R2B2 estimates that the city is blow-

ing the opportunity to develop a $500 million industry in

the city centered around recycling.

"One ought to start with the presumption that a substan-

tial portion of the material in the city's waste stream, ifit's

separated out ahead of time, is not waste. In fact it's a raw

material," he says. "Even if landfilling and incineration

were healthful and environmentally benign, they would

be a waste of money." The solution, he says, is to promote

quality control within whatever recycling infrastructure

is set up, and to create incentives like paying for tenant

associations and businesses to properly sort their trash.

He argues that if the Department of Sanitation would fund

facilities that practice quality recycling instead of build-

ing incinerators, the city would have a far cheaper, cleaner

and more efficient waste management program.

"It's foolhardy to give away valuable material,"

Muchnick says. "Folks ought to be able to participate and

get a piece of the pie. It's not just lawyers, investment

bankers, construction folks, and research institutes who

should profit from huge public expenditures on our waste

infrastructure." That idea may end up in the smoke of an

incinerator chimney.

"My parents were sharecroppers," says John Cousar. "I

got a whipping if they caught me wasting things. As for the

politicians, what can you do beyond telling them that the

number of jobs we provide for unskilled people is

important?" 0

Are administrative duties eonsuming too mueh

Money?

those barriers!

We can help you reduce expenses or increase

operating effieieney! Our fees are Oexible.

Breakthrough

Office Services

and Consulting

334 East 74 Streeet

Suite 1E

New York, New York

10021

Call for a brochure

212-249-8660

Dorothy Turnier

Principal

Specializing in

Non-Profit Organizations

Financial

'bookkeeping services

budget preparation

and tracking

'periodic financial

statements

all. on an automated basis

Administrative

'co-ordinating volunteers

answering correspondence

scheduling meetings

mailings ... you name it!

Consulting

CITY UMnS/OCTOBER 1991/115

Charter Revision:

The Big Nothing?

Don't hold your breath for the new

and improved version of New York City government.

BY LISA GLAZER

n November

0

8 ,1989, New

YorkCityvot-

ers stepped

into creaky

polling booths and

were confronted with

a proposal to com-

pletely overhaul the

constitution of local

government-the

New York City char-

ter. By many ac-

counts, the changes

were right up there

with apple pie and

motherhood. Their goals included: Fair and effective

representation! Increased public participation! A shift

from crisis management to long-term planning! Who

could turn this down?

When the votes were counted, charter revision was

duly approved and nearly two years later city government

appears transformed. The eight-member Board of Estimate

has been abolished and the City Council is expanding to

51 members, nearly half of them African-American or

Latino. Borough presidents have lost much of their power

while the City Planning Commission has acquired consid-

erable clout. Equally important, new rules are in place for

the procedures at the heart of public policy work-

budgeting, contracting and land-use decision making.

"This shows that even in New York City, change can

happen and it can happen quickly," says Gordon Campbell,

deputy director of the mayor's office of operations, which

oversees charter implementation. "What we're doing is

shaping how the city will look and operate into the next

century. When you think about it, it's very heady stuff."

Nonetheless, New York City still has a very powerful

mayor, a Ci ty Council under the iron rule of Speaker Peter

Vallone and an incredibly complex bureaucracy. Not

exactly a radical reversal of history. New offices intended

1S/0CTOBER 1991/CITY UMRS

to make government

user-friendly have

been dropped like hot

potatoes, ostensibly

because of budget

cuts. And potentially-

historic guidelines for

community-based

planning and the sit-

ing of city facilities are

muted by purpose-

fully-vague phrases

like "shall consider"

and "may request."

"I'd say we're in the

same place or going

backwards," says Sam

Sue, an attorney from

the Charter Rights Project, which has been monitoring the

changes. "Charter revision raised the expectation that

people would have a role in the planning process. There's

an appearance of this but it's not substantive."

The charter changes are as vast as city government itself

and it's hard to get a handle on the big picture. But a close

look at the new land use process reveals disturbing trends.

The revised procedures are more complicated than ever;

you need a guidebook to find out when development plans

can bounce from the expanded City Planning Commission

to the City Council, the mayor and then back to the

council. There are extra public hearings along the way,

and new opportunities for early information sharing be-

tween community boards, developers, and city officials.

But, as Marcy Benstock, the director of the Clean Air

Campaign, exclaims, "Talking is not Democracy! It's nice-

but it's not the same as having real policy choices in the

use of public resources."

The true effect of charter revision won't be clear for

another few years, when (and if) the development slump

ends, the new City Council matures and community

groups and city agencies become familiar with the nuts

and bolts of charter change. At the moment, the range of

opinion reflects a diversity of attitudes towards city gov-

-

ernment. Technocrats inside the system see helpful im-

provements while community advocates see extra bu-

reaucratic layers that could actually increase the gulf of

disaffection between New Yorkers and their leaders.

The organizing process that evolved around the charter

issue shows how difficult it is to bring government closer

to the people. The starting point for debate was the charter

itself-hardly popular reading material among the New

York City masses. Because of this, many community

groups and individuals were alienated

from the outset. Once the charter re-

visions were passed and it was time to

Still, the news isn't entirely bleak. There's a small

possibility that CPIC may eventually be refunded, and in

the meantime the 15 appointed members ofthe commis-

sion are continuing meeting monthly in Stein's office.

Their early work-conducting a feasibility study of

cablecasting City Council proceedings-is complete and

Rojas is pursuing programming for a five-channel munici-

pal cable television network that will be starting this

winter. The public access channels will include programs

produced by city agencies and one

channel is slated for gavel-to-gavel

coverage of City Council proceed-

draft new rules, much of the "commu-

nity" advocacy was done by a core

group of professional organizers, most

of them with law degrees. This is better

than no public input whatsoever, but

it's hardly a historic redistribution of

power.

The Independent

Budget Office

was dead on

ings-if funding is approved. An-

other project, compiling a listing of

computerized information from city

agencies that is available to the pub-

lic, is being completed by the staff at

Stein's office.

If the Commission on Public In-

formation and Communication ex-

pired slowly and painfully, the

Independent Budget Office was dead

Even the policy junkies found charter

revision rough going at times. "It's civic

castor oil-good for you but very hard

to swallow," says Gene Russianoff, a

arrival.

government expert from the New York

Public Interest Research Group

(NYPIRG). "This is the rules of the game stuff-it's dense,

very tough going. About a third of my work involves the

process of government and I have perpetual angst over

whether it makes a difference or is just a hill of beans."

He pauses to consider the charter changes, which

NYPIRG supported, and comments, "I think they do make

a difference." Longer pause. "But how much of a differ-

ence is very hard to know."

Response to Frustration

The 15-member Charter Revision Commission held 29

public meetings, 25 public hearings and hundreds of

informal listening sessions before they drafted their final

proposals. They held meetings in every single borough,

listening to suggestions and complaints about city govern-

ment. As the months went by, one point became crystal

clear: New Yorkers find government remote, uncaring and

difficult to navigate.

In response to this outpouring of frustration, the Char-

ter Revision Commission mandated the creation of a

numberofnew government entities. Two new offices, the

Independent Budget Office and the Commission on Public

Information and Communication, were meant to provide

much-needed details about how government operates-

from an independent vantage point outside of City Hall.

Another good government reform was a plan to expand

staffing at community boards, the most local branch of city

government.

These changes-the icing on the cake of charter revi-

sion-have been rendered virtually meaningless. The

Commission on Public Information and Communication

(CPIC) set up shop in a small room on the 20th floor of the

municipal building in November,1990. Less than a year

later their doors were closed because of the budget crisis.

The commission's executive director, Maria Teresa

Rojas, is working for the Department of Telecommunica-

tions, but her support staff has been laid off. Calls to CPIC

are transferred to the office of City Council President

Andrew Stein, where a receptionist answers, ''I'm taking

calls but I don't know what the commission was."

on arrival. The official reason was

budget constraints, but the real prob-

lem was the city's political leaders,

who have shown very little interest in dispensing essen-

tial financial information to City Council members, com-

munity boards and the general public.

"Defunding the Independent Budget Office was a very

cynical act," notes Penelope Pi-Sunyer, executive director

of Alterbudget. Pi-Sunyer says that a 10-member advisory

committee-appointed by the mayor, the City Council,

the comptroller and the borough presidents-labored

fruitlessly for months to choose an executive director for

the office.

Because of the lack of progress toward the Independent

Budget Office, some advocates say a lawsuit may be in the

works. Pi-Sunyer says she will continue to fight for its

creation. "It's very important because people still have

trouble getting access to timely and reliable budget infor-

mation. A lot of trouble. Even City Council members can't

get information. Here at Alterbudget, we're not finance

fanatics-we're backed by service groups-but you have

to find out where the dollars are going so you can translate

rhetoric into reality."

Plans to increase funding for community boards, which

receive $141,818 each, led to another exercise in dashed

expectations. According to a number of people closely

involved in crafting the charter changes, an early version

included very clear language requiring new funding for

professional planners at each community board. But some

board leaders said they didn't necessarily want full-time

planners-they might prefer a consultant plus an extra

secretary or outreach staff.

In the charter revision universe, wording is everything,

and the final charter proposals authorize but do not

mandate new professional staff for the boards. Not

surprisingly, not a penny extra was allocated. With quiet

irony, Miriam Josephs from the Office of Management and

Budget explains, "The community boards wanted more

flexibility ... they got more flexibility than they hoped for."

Contradictory Goals

The Charter Revision Commission reached for contra-

dictory goals when it revised the basic formulas of land

CITY UMITS/oCTOBER 1991/17

use policy. The commissioners sought greater efficiency

and more public participation. The end result is a process

that even Eric Lane, the former counsel for the commis-

sion, describes as "cumbersome."

Under the old charter, development proposals went

through the city's lengthy uniform land use review process

(ULURP). To simplify, plans went from community board

to the City Planning Commission and finally on to the

Board of Estimate, where the ultimate decisions were

made.

The new system is fairly similar in the beginning,

except that community boards are required to be invited

to special environmental hearings known as "scoping

sessions" at the preliminary stages of a development

proposal-before it even starts ULURP. After that, business

basically proceeds as usual until a proposal reaches the

City Planning Commission, which has been enlarged from

seven to 13 members and given much greater authority.

Sometimes the planning commission is the end of the

line, but in some instances proposals move forward to the

City Council. Multiple factors determine how and when

a development can be considered by the City Council,

which can reverse or modify the City Planning

Commission's decision. Then the mayor can veto the

Council's decision ... but if two-thirds of the City Council

comes together, they can reverse the mayor's veto. Call it

the ping-pong approach to land use.

"Things are procedurally much worse," says Sue from