Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Journal of Visual Culture: Books

Hochgeladen von

lthrasherOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Journal of Visual Culture: Books

Hochgeladen von

lthrasherCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

journal of visual culture

Books

Cecilia Novero, Antidiets of the Avant-Garde: From Futurist Cooking to Eat Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. 368 pp. ISBN 978-0816646012. The massication of food TV shows and magazines as well as lines of designer cookware evidence the contextualization of the culinary within consumer capitalism. It is difcult to ignore this now bloated industry as it instructs in good taste and parades appealing food identities pre-designed to satisfy and stimulate more demand. This cuts to the point: embodied within the glossy images of feta-stuffed red peppers, pan-seared tuna steaks, and chocolatedipped strawberries are values and drives. What often goes unnoticed are the subtle ways that food practices can reify nationalist discourses and stabilize subjectivities, forming relationships between social semiotic orders and the materiality of the body. In other words, if you are what you eat, then you are not just materially constituted by food but socially constituted as well. This is precisely how Cecilia Novero, thinks about food in her new book, Antidiets of the Avant-Garde. And this is precisely why Antidiets is timely; read from todays food-obsessed perspective, revisiting the subversive movements of the avant-garde is a much-needed dirty nger stuck right in the center of the new celebrity-chef-pie. On the surface, Noveros project is to explore the performative qualities in food and eating as they manifest themselves in avant-garde manifestos, magazines, declarations, instructions, and so forth, as well as, surprisingly, in actual cookbooks (p. ix).The immediate focus, then, is on what Novero terms antidiets or the sometimes disgusting, sometimes wild, and sometimes aggressive avantgarde food-as-art engagements that shatter the cultural senses, disrupt elitist ne dining experiences, scoff at the Italian way to eat, spoil the comforting smells that make us feel at home with food and, overall, reject the dominant model of eating. But the book also delves into the less obvious forays within this art history that are not already accessible within singular texts of individual avant-garde movements. In fact, the most compelling ingredient of Antidiets is Noveros effort to explore both the early avant-garde of the 1930s and the later neo-avantgarde of the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, Noveros discussion of Filippo Tommaso

journal of visual culture [http://vcu.sagepub.com] SAGE Publications (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC) Copyright The Author(s), 2010. Reprints and permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalspermissions.nav Vol 10(2): 266273 DOI 10.1177/1470412911413187

Books

267

Marinetti, Walter Benajmin, and Daniel Spoerri, as well as several other artists who exhibited at the Eat Art Gallery, proves satisfying largely because Novero shows how, in their own unique ways, these artists believed that food could reify or subvert governing orders; she explains how Marinetti, to take just one example, campaigned to end the mass consumption of pasta in Italy because the resulting thick and heavy body was anti-Modern and would only, in his view, encourage loud, bombastic nationalistic discourses (pp. 268). In short, Novero demonstrates how each avant-garde artist identied hegemonic mechanisms of power rooted in naturalized material practices, right down to what was being served at the dining-room table. However, Antidiets is most sophisticated when it investigates the strange oppositions at play within and among avant-garde movements, such as the continual dedication to alternative futures, by returning to basic human needs or by incorporating whatever is already-present. This particular mode of action is witnessed in the neo-avant-garde practice of eating art to incite a rejection of art as capitalist production, a literal consumption and digestion that destroys art instead of preserving art, an excrement of art meant to revitalize art (p. 256). Interestingly, it is while tracing this knotty history that Noveros text performs the avant-garde act of revision, moving ever forward through the avant-garde by returning, again and again, to what has already been discussed; Novero never ceases to re-visit a prior discussion in the midst of a new one in order to (re) write the avant-garde. For example, in chapter three, while Novero details how Walter Benjamin views a Modern chemically-oriented diet as offering nothing more than the repetition of the same, Novero recalls chapter one to draw a contrast with the Italian Futurists who embraced a chemical diet precisely because it leaves the need for cooking behind and transforms it thus into a realm of experimentation (p. 99).Yet, it is precisely when highlighting this moment of contrast that Novero turns around to embrace a similarity between Benjamin and Italian Futurists like Marinetti; she suggests that both, despite their different views of the Modern diet, hope to resist enshrinement in heritage (p. 100). And this point of similarity recalls an earlier point of contrast, where Novero is attentive to Marinettis amboyant protests against preserving history, even while he undertakes an assiduous recording of all the documents, conservations, and inventions (p. 4). This is just a taste of the layers baked into this book. The points of contrast are nearly endless, some surprisingly far apart and subtle. For instance, at one point in chapter two, Novero attends to the desire of Tristan Tzara, Walter Turner and others in the Dada movement to emphasize indigestion, excess, vomit, and diarrhea block in order to render inefcient the principles shoring up consumer society and the capitalist system (p. 87), and then, much later, in chapter ve, she cunningly re-visits this counter-physiology to situate Piero Manzonis living body sculptures as well as his belief in creation as a constant act of consumption (p. 252). Her lack of hesitancy to re-visit the Dada movement at this particular moment serves as a constructive point of contrast for Manzonis art of consciousness that takes shape in and through living matter (p. 248).The fun and the intellectual curiosity of this book are then, discovered as each chapter

268

journal of visual culture 10(2)

builds layers of complex denials and afrmations between successive writers and philosophers forming the various historical avant-garde movements, thereby rewriting the history of the avant-garde as one boiling over with slippages. If Antidiets ever too strictly territorializes the avant-garde, it does so as a result of its most compelling feature its dependence on contrast and comparison. Although the opening chapters discussion of Modernism, Italy and the First World War serves as a useful reference point for a discussion of later avant-garde artists, the contextualization given to the Italian Futurists in this chapter seems, at times, neglected in subsequent chapters, which lack the same attention to the historical moment. For instance, despite the fact that Spoerris 1960s petried landscapes of food are well discussed in terms of being a response to Western consumer society and clearly follow from the irreverent manner of the Dada movement (pp. 14651), Novero never fully explains how Spoerris choice to re-adopt a view from and of the stomachs labyrinths and instruments (p. 150) through his trap paintings could, right at that historical moment, extend the avantgarde in the way that they did. Each new artwork is situated primarily in relation to the individual artists beliefs about the economic system or to philosophers previously discussed in the text, with little discussion of what it was about the type of extension the movement toward aggressiveness or passivity with food, toward enticement or disgust that highlighted events of that time period. As one example, the inuence of the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze on the neo-avantgarde practice of Spoerri is made clear, but the discussion would benet from a longer and more overt connection to the broader rejection of traditional Marxist ideas about the structural realities of production or the social engagement with civil rights movements of the time. Additionally, the book spins its own internal discussion into a complex of productive connections but then ends without looking forward to the place and role of the avant-garde today. This was a bit disappointing because it is difcult not to apply everything in this book to today, and it is equally difcult not to desire Novero to continue the discussion. Without question, though, the socially conscious and shocking avant-garde food artworks explored in the book are not very far distanced from what many artists are still doing with food. When one considers James Reynolds (2009) austere food photographs of a Death Row prisoners last meals or John Rubins (2010) Conict Kitchen in Pittsburg, it is worth wondering, or drooling over, what Novero could do with all that fresh material. Nevertheless, pointing out these missed opportunities may only be accusing Novero of failing to do everything, since what she does do with and through this book is more than enough to walk away feeling full. Readers of Antidiets need not feel dismayed at any perceived oversight or over-emphasis, since Noveros approach to the avant-garde through food is, as she explains in her introduction, intent on resisting any essentializing and, consequently, asks its reader to accept it as an open site (p. xxxvi). Thus, Antidiets beckons for its own antidiet, and responding, even if in distaste, would only be tting. So even if the book should be bolstered by historical detail or could be extended by folding in discussion of food art today, responding to this book by politely lifting the napkin to the mouth will be difcult to do. In fact,

Books

269

even if this book, like each avant-garde movement, is destined to failure as it is written over and shoved into historical insignicance, then its robust discussion ensures that it will do so along the trail of the avant-garde, as an experiment designed to release its readers from majoritarian perspectives on the body, pleasure, and society. And the success of that experiment, even if short-lived, is felt the moment the book is put down to turn on the Food Network or to nd a new place to go out to dinner, and the stomach feels unsettled about what is being offered and why. References

Reynolds, J. (2009) Last Suppers: About James Reynolds. URL (consulted 3 Nov. 2010): http://www.jwgreynolds.co.uk/index.php?/last-suppers/ Rubin, J. (2010) John Rubins Current/Upcoming Work. JON RUBIN. URL (consulted 3 Nov. 2010): http://www.jonrubin.net/

David Gruber North Carolina State University [email: Drgruber@ncsu.edu]

Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton, Cartographies of Time: A History of the Timeline. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010. 272 pp. ISBN: 1-568987633 May not duration be imitated and represented as effectively to the senses as distinctly as space, and may not intervals of time be as easily counted in degrees? The seductive analogy of mapping historical time is evident in the title of this history of the timeline by Daniel Rosenberg of the University of Oregon and Anthony Grafton of Princeton. The question was posed in the mid-18th century by Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg, a Parisian doctor, botanist, philologist and aspiring arms supplier to the American Revolution (defeated in that capacity by Beaumarchais). This was a time of signicant innovation in visual culture, yet, as Rosenberg has said, historians do not study timelines; an object central to many peoples learning of history has gone largely unnoticed. Cartographies of Time is therefore not just a welcome book, it is a necessary one which deals with a neglected aspect of past historiography and an important cultural form.The most signicant prior work in this area is that of the authors themselves, including Rosenberg on Joseph Priestleys graphic invention of modern time (2007) and Graftons intensive two-volume study of Joseph Scaliger (1993[1983]), so it is fortunate that these two have now pooled their expertise. How should time be mapped visually? The answers emerging from this richly illustrated history demonstrate vividly the correspondence between certain distinctive visual forms and particular cultural models of time.Although, as Alfred Gell pointed out in Anthropology of Time (1992), even to refer to such a model is to beg the question: a society may have a model of the relationship between events, or between now and the past, but not necessarily have a model of time

270

journal of visual culture 10(2)

per se. Feeney remarked in Caesars Calendar (2007) the near-impossibility of our recovering in imagination the character of events before we had a standardized numerical grid for history, and emphasized the recency of its invention. Rosenberg and Grafton develop this theme to show how the line, visible or implied as a metaphor for time, is a product of only the last 250 years.They document a series of key inuences on chronology and chronography: the explosion of conicting sources faced by Renaissance scholars, the realization that astronomical records might be used as a historical clock to correct dates corrupted or lost, the eschatological motive (many chronologies and chronographics mapped the past in order to predict the future), and the pain experienced by Christian chronologers as evidence accumulated in the form of reliable records from other cultures and the growth of deep time through geological investigation that the Bible could no longer be treated as history. Perhaps there could have been more on Descartes essential groundwork in visualizing number as line, and the crucial proposition of Newton (so exciting to DAlembert that he featured it in the Discours Prliminaire as well as his article Chronologie for the Encyclopdie) that time is a measurable container analogous to space. Pivotal in the narrative running from Eusebius to the present day, and literally central in Cartographies of Time, is the work of a fervent admirer of Newton: Joseph Priestley, preacher, scientist and radical, and, like BarbeuDubourg, a friend and correspondent of Benjamin Franklin. While many of the charts in the book are rich in graphical conceits, such as trees, rivers, streams, chains and wheels of time, Priestleys Chart of Biography (1765) is wonderfully minimal and arguably egalitarian with its spread of 2000 undifferentiated named lifelines, an arithmetical presentation appropriate to Priestleys scientic and Dissenting philosophy and symptomatic of mechanical sympathies in those optimistic, improving times. His depiction shows exactly that homogenous and empty time is anathematized by Walter Benjamin (2001[1940]), but it is remarkable how the empty spaces, the drifts and clusters of names, in themselves convey meaning without the need for additional graphical rhetoric. The account of Priestleys achievement might have said more about another of his innovations: the visual representation of uncertainty, a vital aspect of chronography ignored in most visualization then and since. The 19th century brings in chronographical games, mostly intended to be educational. Occasionally ingenious, these represent in some ways a nadir of the discipline, essentially childish and hardly a tool for investigation or serious thought. Nevertheless, it is nice to learn that a chronographic game was explicitly designed by Mark Twain so as to be winnable by any player knowing a lot of minor events, as much as by someone who knew the dates of the monarchs and battles so beloved of conservative champions of the Important Date. Profoundly knowledgeable in historiography, the authors write sensitively about the visual, and effortlessly connect the two. For them the graphical is not a childish substitute for the sophistication of words but an essential counterpart. An admirable feature of the books design by Jan Haux is the synergy of the text and illustrations. The gures are printed close to the relevant text, the captions

Books

271

are informative, and the authors draw out with verve the features they want the reader to notice. The closing chapters are more cursory, touching on timelines as public monuments, timelines as art including Maciunas chart of time and space-based art for Fluxus, John Cages graphical scores, and Shapolsky et al.s Manhattan Real Estate Holdings. Some exclusions are a little surprising: if Mareys chronophotography is in, should the comic strip and the lm storyboard be out? The exhibition timelines of Charles and Ray Eames, the grandest of which mounted physical historic objects onto extended graphical representations of time, do not appear. Michael Twyman at Reading, author of signicant work in this area prior to the authors own, seems not to be acknowledged. But these are quibbles about a book whose long historical perspective is one of its nest features. In the middle of discussing modern grand timelines in museums and public spaces, the authors tell us of Augustus carved fasti consulares of the rst century BCE; a frivolous modern timeline on a folding ruler is juxtaposed with Drer, and Sarah Fanellis Tate Artist Timeline with Piranesi. It would be nice to believe that chronography will no longer be unimportant once this exceptionally well researched book is widely seen. References

Benjamin,Walter (2001[1940]) On the Concept of History, trans. Dennis Redmond. URL (consulted Oct. 2010). http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/ history.htm Feeney, Denis (2007) Caesars Calendar: Ancient Time and the Beginnings of History. Berkeley: University of California Press. Gell, Alfred (1992) The Anthropology of Time: Cultural Constructions of Temporal Maps and Images. Oxford: Berg. Grafton, Anthony (1993[1983]) Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Rosenberg, Daniel (2007) Joseph Priestley and the Graphic Invention of Modern Time, Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 36(1): 55103.

Stephen Boyd Davis Middlesex University [email: S.Boyd-Davis@mdx.ac.uk]

Roy Harris, The Great Debate about Art. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2010. 130 pp. ISBN 978-0984201006 Harris suggests that the question that drives the Great Debate about Art What is art? only really becomes a question with the advent of the inherently ambiguous doctrine of art for arts sake, originated by Benjamin Constant in 1804. This claim of artistic autonomy stands in direct opposition to assumptions of arts responsibility toward society, deeply embedded in the Western tradition going back to Plato and Aristotle. With arts liberation from this social responsibility, a certain critical space is opened up for the question of arts identication

272

journal of visual culture 10(2)

and evaluation apart from any didactic function, and Harris identies three paradigmatic attempts to answer this question, each corresponding to an established position recognizable in the discussion of art today: institutionalism, idiocentrism, and conceptualism. In the view of institutionalists, certain authoritative voices (curators, dealers, critics, patrons, teachers, historians, etc.) determine the answer to the question of what art is, and society simply accepts this determination. Idiocentrics counter that art is an essentially individual experience, intrinsically private (Harriss example is a toothache), and that no amount of institutional control can produce an authentic encounter with a work of art. Finally, conceptualists hold that the concept alone, in abstraction from any material realization, is all that matters (p. 33) a view that Harris characterizes as sounding like a badly digested dose of Hegel. At stake in the formulation of this question and its response is the very epistemological category of art, which Harris argues ultimately collapses under the weight of the mountain of language piled on top of unsuspecting works of art, language so impenetrably dense that the work of art itself becomes completely obscured. The result is that we are no longer in a position to answer, or even to ask the question of what art is, and perhaps more importantly what art is not. Artspeak, artbollocks, art journalese, pseudospeak, mediaspeak, claptrap, and jargon are just some of the keywords for the argument that Harris makes on this point concerning the collapse of art as an epistemological supercategory, his claim being that we are still living amid the debris resulting from that collapse. Consequently, one of Harriss main claims in this slight pamphlet is that the Great Debate about Art is not at all great because it is not really about art any more, not since the irrevocable failure of art and art criticism to repulse Dada and other forms of modern anti-art, all too hastily assimilated under the conceptual category of art. Harriss pronouncement is that the Great Debate is now dead (p. 124), but not because the debate itself has died out just the opposite; the controversy and clamor surrounding the provocation of absurdity have produced complete obfuscation,reduc[ing] the Great Debate to a dialogue of the deaf (p. 42). Harriss account of modern arts implosion is basically that of a failed dialectic, where the negative moment is misrecognized and therefore the movement falters: Dadas negativity failed to emerge properly because the sophists of art criticism and art history have mistaken the subversive threat posed by this antiart as an opportunity for a simple expansion of the concept of art which for Harris is equivalent to declaring atheism to be a religious doctrine acceptable to the orthodox church (p. 86). Rather than sublating the profound negativity of Dada, and redening the epistemological boundaries of the category of art, we have effectively allowed the absurd provocation to blind us to the difference between art and anti-art: Like oncoming car headlights, the glare of absurdity blinds one to what lies behind it (p. 47). What lies behind Dadaist iconoclasm is the struggle between the visual and the verbal in aesthetic representation, namely the revolutionary attempt to liberate art from the hegemony of language (p. 63), which Harris argues is constitutive for mimetic representation, but he asserts that this is also an essential site of conict for non-mimetic modes of

Books

273

art. Modern art does not merely frustrate our perception in visual terms, rather our inability to name what is presented also communicates a profoundly antilinguistic message (p. 70). Again, the focus is on the misrecognized negativity of modern art, which presents a world out of joint in both verbal and visual terms. Ultimately, Harris grounds his entire argument on the negative function of anti-art, but this is also the most problematic element in this work. For one thing, this negative articulation of the concept of art is the counter-product of universal education: artists cultivate difculty and obscurity in order to be regarded as intellectuals, confounding a public suddenly in possession of various forms of literacy, putting the arts beyond the intellectual reach of the hoi polloi.This deliberate unintelligibility necessitates a supplement, an intricate apparatus of theoretical support, without which the artifact remains effectively illegible, but the explanation itself, cast in esoteric terms accessible only to intellectuals and specialists, reemphasizes this problem of indeterminacy. Arts negation follows directly, then, from the fact of its intelligibility via education. Second, the negativity that Harris attributes to Dada is not entirely consistent that is to say, Harris seems to distinguish within Dada between good and bad anti-art, the good being the most emphatic expressions of negativity. But this is not entirely consistent with Hans Richters own insistence on the retention of the paradox that Dada is both positive and negative, manchmal als Kunst und dann wieder als Verneinung der Kunst [sometimes as art and then again as the negation of art] (Richter, 1978: 9).The one-sided portrayal of Dada as anti-art, as essentially negative, is exactly what Richter rejects as a myth. But perhaps Harris must hold on to this mythologization if he is to present Dada as the end of the debate about art, a negative moment to which the entire Western tradition has succumbed. Readers familiar with the line of pamphlet-polemics issued by the Prickly Paradigm Press will appreciate the critical accounting Harris makes of the complicated relationship between word and image, and observant readers will recognize in this argument an attempt at revitalization. Reference

Richter, Hans (1978) Dada-Kunst und Antikunst: Der Beitrag zur Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts. Mit einem Nachwort von Werner Haftmann. Kln: DuMont Buchverlag.

Kurt R. Buhanan University of California, Irvine [email: kbuhanan@uci.edu]

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- TSR 9440 - Ruined KingdomsDokument128 SeitenTSR 9440 - Ruined KingdomsJulien Noblet100% (15)

- Vietnamese Alphabet and PronounDokument10 SeitenVietnamese Alphabet and Pronounhati92Noch keine Bewertungen

- SubcultureDokument35 SeitenSubcultureiosifelulfrumuselul100% (1)

- Lewis - The Condition of ImprovisationDokument8 SeitenLewis - The Condition of ImprovisationAnonymous uFZHfqpBNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Dawn To Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 To The PresentDokument14 SeitenFrom Dawn To Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 To The PresentFiona13% (8)

- Cookbooks India Appadurai 1988Dokument23 SeitenCookbooks India Appadurai 1988Keith Egan100% (1)

- Foster Hal Recodings Art Spectacle and Cultural Politics PDFDokument260 SeitenFoster Hal Recodings Art Spectacle and Cultural Politics PDFLaura FlórezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2002 CT Saturation and Polarity TestDokument11 Seiten2002 CT Saturation and Polarity Testhashmishahbaz672100% (1)

- COACHING TOOLS Mod4 TGOROWDokument6 SeitenCOACHING TOOLS Mod4 TGOROWZoltan GZoltanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asimovs Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Isaac Asimov 941pDokument1.004 SeitenAsimovs Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Isaac Asimov 941p6ylinder100% (3)

- Renaissance in Italy (Vol. 1-7): Complete EditionVon EverandRenaissance in Italy (Vol. 1-7): Complete EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical AnthropologyDokument25 SeitenCritical AnthropologyBenny Apriariska Syahrani100% (1)

- The Theater of Truth: The Ideology of (Neo)Baroque AestheticsVon EverandThe Theater of Truth: The Ideology of (Neo)Baroque AestheticsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eri PBDokument307 SeitenEri PBpepe100% (7)

- Preboard Practice PDFDokument25 SeitenPreboard Practice PDFGracielle NebresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food The ArtsDokument138 SeitenFood The ArtsKatarina Tešić100% (4)

- Seeing All Things Whole: The Scientific Mysticism and Art of Kagawa Toyohiko (1888–1960)Von EverandSeeing All Things Whole: The Scientific Mysticism and Art of Kagawa Toyohiko (1888–1960)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Appadurai Arjun 1988 How To Make National Cuisine en Comparative Studies in Society and History Vol 30 No 1Dokument23 SeitenAppadurai Arjun 1988 How To Make National Cuisine en Comparative Studies in Society and History Vol 30 No 1Anku Bharadwaj100% (1)

- A Short History of Spaghetti with Tomato Sauce: The Unbelievable True Story of the World's Most Beloved DishVon EverandA Short History of Spaghetti with Tomato Sauce: The Unbelievable True Story of the World's Most Beloved DishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asimovs Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Isaac Asimov 941p PDFDokument1.004 SeitenAsimovs Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Isaac Asimov 941p PDFMuhammad Saqlain100% (3)

- The Enlightenment and religion: The myths of modernityVon EverandThe Enlightenment and religion: The myths of modernityNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Ben Highmore) Michel de Certeau Analysing CulturDokument201 Seiten(Ben Highmore) Michel de Certeau Analysing CulturDiego MachadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proletarian Nights: The Workers' Dream in Nineteenth-Century FranceVon EverandProletarian Nights: The Workers' Dream in Nineteenth-Century FranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Byzantine CutleryDokument27 SeitenByzantine CutleryDimitris BoukasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Members List Iei Mysore Local CentreDokument296 SeitenCorporate Members List Iei Mysore Local CentreNagarjun GowdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life Assessment of High Temperature HeadersDokument31 SeitenLife Assessment of High Temperature HeadersAnonymous UoHUag100% (1)

- Eating the Enlightenment: Food and the Sciences in Paris, 1670-1760Von EverandEating the Enlightenment: Food and the Sciences in Paris, 1670-1760Noch keine Bewertungen

- Food in Painting From The Renaissance To The PresentDokument241 SeitenFood in Painting From The Renaissance To The Presentfcrevatin86% (7)

- Bourdieu TasteDokument387 SeitenBourdieu TasteMarco PogacnikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal KORELASI ANTARA STATUS GIZI IBU MENYUSUI DENGAN KECUKUPAN ASIDokument9 SeitenJurnal KORELASI ANTARA STATUS GIZI IBU MENYUSUI DENGAN KECUKUPAN ASIMarsaidNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Taste of Art: Cooking, Food, and Counterculture in Contemporary PracticesVon EverandThe Taste of Art: Cooking, Food, and Counterculture in Contemporary PracticesSilvia BottinelliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palma, Pina - Savoring Power, Consuming The Times. The Metaphors of Food in Medieval and Renaissance Italian Literature PDFDokument443 SeitenPalma, Pina - Savoring Power, Consuming The Times. The Metaphors of Food in Medieval and Renaissance Italian Literature PDFBenedict HandlifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- On the Importance of Being an Individual in Renaissance Italy: Men, Their Professions, and Their BeardsVon EverandOn the Importance of Being an Individual in Renaissance Italy: Men, Their Professions, and Their BeardsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mar García RanedoDokument10 SeitenMar García RanedomargarciaranedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tasting Modernism: An IntroductionDokument10 SeitenTasting Modernism: An IntroductionvalesoldaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Una Historia de La Verdad en Occidente Ciencia ArtDokument6 SeitenUna Historia de La Verdad en Occidente Ciencia Artvalelu.20069Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Society Tut 2Dokument5 SeitenAncient Society Tut 2ittifaqanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food in Italian History, Society and ArtDokument5 SeitenFood in Italian History, Society and ArtKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sollegue TFA166 LL1Dokument1 SeiteSollegue TFA166 LL1Maja Angela Victoria SollegueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modernism MummifiedDokument12 SeitenModernism Mummifiedsfisk004821Noch keine Bewertungen

- ERJAVEC Introducción Postsocialism, Posmodernis and BeyondDokument30 SeitenERJAVEC Introducción Postsocialism, Posmodernis and Beyondivonne sbNoch keine Bewertungen

- ContentServer PDFDokument25 SeitenContentServer PDFJulie Bustos VelandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Italian Renaissance Research PaperDokument7 SeitenItalian Renaissance Research Paperajqkrxplg100% (1)

- From Chinese Cosmology to English Romanticism: The Intricate Journey of a Monistic IdeaVon EverandFrom Chinese Cosmology to English Romanticism: The Intricate Journey of a Monistic IdeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HEINICH, Nathalie. What Does Sociology of Culture' MeanDokument9 SeitenHEINICH, Nathalie. What Does Sociology of Culture' MeanWeslei Estradiote RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carrier - History and Tradition in Melanesian AnthropologyDokument242 SeitenCarrier - History and Tradition in Melanesian AnthropologyvarnamalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renaissance Research Paper OutlineDokument7 SeitenRenaissance Research Paper Outlinegw163ckj100% (1)

- Narratives EnglishDokument26 SeitenNarratives EnglishNicolás Perilla ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 10 17 - RomancingDokument15 Seiten2015 10 17 - RomancingD-2o4j48dol20iilylz0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Feasts, Fasts, Famine: Food/or Thought: Pat CaplanDokument35 SeitenFeasts, Fasts, Famine: Food/or Thought: Pat CaplanFarah Ridzky AnandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Renaissance in Italy (Complete 7 Volumes)Von EverandThe Renaissance in Italy (Complete 7 Volumes)Noch keine Bewertungen

- New ModernsDokument15 SeitenNew ModernsSimon O'SullivanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trivellato, Microstoria:Microhistoire:MicrohistoryDokument13 SeitenTrivellato, Microstoria:Microhistoire:MicrohistoryMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper RenaissanceDokument7 SeitenResearch Paper Renaissancemajvbwund100% (1)

- Garc-A-2013-The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean AnthropologyDokument20 SeitenGarc-A-2013-The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean AnthropologyJulieta ChaparroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blackwell Publishing American Anthropological AssociationDokument4 SeitenBlackwell Publishing American Anthropological AssociationAnth5334Noch keine Bewertungen

- Why Food Matters IntroductionDokument16 SeitenWhy Food Matters IntroductionAngelica ValeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Issue 3 Volume 7 Literophile PDFDokument28 SeitenIssue 3 Volume 7 Literophile PDFkousikNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Council For Traditional Music Yearbook For Traditional MusicDokument5 SeitenInternational Council For Traditional Music Yearbook For Traditional MusicL. De BaereNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To The NDQ Special Volume On SlowDokument5 SeitenIntroduction To The NDQ Special Volume On SlowbillcaraherNoch keine Bewertungen

- CR David CahillDokument11 SeitenCR David CahillCorbel VivasNoch keine Bewertungen

- English 6, Quarter 1, Week 7, Day 1Dokument32 SeitenEnglish 6, Quarter 1, Week 7, Day 1Rodel AgcaoiliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Direct and Indirect Pulp CappingDokument9 SeitenJurnal Direct and Indirect Pulp Cappingninis anisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test 1801 New Holland TS100 DieselDokument5 SeitenTest 1801 New Holland TS100 DieselAPENTOMOTIKI WEST GREECENoch keine Bewertungen

- Zimbabwe - Youth and Tourism Enhancement Project - National Tourism Masterplan - EOIDokument1 SeiteZimbabwe - Youth and Tourism Enhancement Project - National Tourism Masterplan - EOIcarlton.mamire.gtNoch keine Bewertungen

- C7.5 Lecture 18: The Schwarzschild Solution 5: Black Holes, White Holes, WormholesDokument13 SeitenC7.5 Lecture 18: The Schwarzschild Solution 5: Black Holes, White Holes, WormholesBhat SaqibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quadratic SDokument20 SeitenQuadratic SAnubastNoch keine Bewertungen

- Northern Lights - 7 Best Places To See The Aurora Borealis in 2022Dokument15 SeitenNorthern Lights - 7 Best Places To See The Aurora Borealis in 2022labendetNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA 2nd Sem SyllabusDokument6 SeitenMBA 2nd Sem SyllabusMohammad Ameen Ul HaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facts About The TudorsDokument3 SeitenFacts About The TudorsRaluca MuresanNoch keine Bewertungen

- T2 Group4 English+for+BusinessDokument8 SeitenT2 Group4 English+for+Businessshamerli Cerna OlanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industry GeneralDokument24 SeitenIndustry GeneralilieoniciucNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacy System Project PlanDokument8 SeitenPharmacy System Project PlankkumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buku BaruDokument51 SeitenBuku BaruFirdaus HoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Đề Anh DHBB K10 (15-16) CBNDokument17 SeitenĐề Anh DHBB K10 (15-16) CBNThân Hoàng Minh0% (1)

- A List of 142 Adjectives To Learn For Success in The TOEFLDokument4 SeitenA List of 142 Adjectives To Learn For Success in The TOEFLchintyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20 Ijrerd-C153Dokument9 Seiten20 Ijrerd-C153Akmaruddin Bin JofriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service M5X0G SMDokument98 SeitenService M5X0G SMbiancocfNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7540 Physics Question Paper 1 Jan 2011Dokument20 Seiten7540 Physics Question Paper 1 Jan 2011abdulhadii0% (1)

- - Анализ текста The happy man для ФЛиС ЮФУ, Аракин, 3 курсDokument2 Seiten- Анализ текста The happy man для ФЛиС ЮФУ, Аракин, 3 курсJimmy KarashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idoc - Pub - Pokemon Liquid Crystal PokedexDokument19 SeitenIdoc - Pub - Pokemon Liquid Crystal PokedexPerfect SlaNaaCNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Ways To Support Your Babys Learning Today Monti KidsDokument19 Seiten7 Ways To Support Your Babys Learning Today Monti KidsMareim A HachiNoch keine Bewertungen

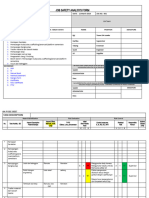

- JSA FormDokument4 SeitenJSA Formfinjho839Noch keine Bewertungen