Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Mark Anderson, Reappraisal of The Total Novel

Hochgeladen von

manderake9999Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Mark Anderson, Reappraisal of The Total Novel

Hochgeladen von

manderake9999Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

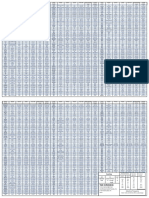

EDITORIAL BOARD

(Department of

Languages, Literatures,

and Linguistics

Syracuse University)

Augustus Pallotta

Editor

Paul Archambault

Review Editor

Beverly Allen

Pedro Cuperman

Kathryn Everly

Ken Frieden

Erika Haber

Harold G. Jones

Dennis McCort

Gerlinde Ulm Sanford

Amy Wyngaard

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Frank Paul Bowman

University of Pennsylvania

Lilian R. Furst

University of North Carolina

Gail K. Hart

University of California, Irvine

Angele Kingue

Bucknell University

Bettina L. Knapp

Hunter College, CUNY

John Kronik

CorneLL University

Lucienne Frappier-Mazur

University of Pennsylvania

Paolo Possiedi

Montclair State University

Nadia A. Saleh

Syracuse University

John Walker

Queen's University, Ontario

ABOUT THE COVER

Author Carlos Fuentes. Photograph

courtesy of Royce Carlton, Inc., New

York.

HELDREF PUBLICATIONS

Director

Douglas J ... Kirkpnt;riol(

Prodllcfton Editor

S tlzabeth Fox well

Ediforial Production Director

Jennifer Pricola

S,>ealive Director.

CaT1l'len S. Jessup

Q,t tpUic A rtisl

Janrieite Whippy

Production Manager

R ichard Pepple

Cl rcLilal/on Diroctlfr

Fred HU.ber

F'uljillmenr a/ld Reprints-Manager

Jelln Kline

Mal'/wting.Ar:(Dirl!ctor

Owe.n T. D a'il j g,c

PmmotionS Associqre

Uwl Basaninyen-zi

Advertising M anager

Alison Mayhew .

'Logi$tif;$ (md fi'qcilitie$ Manager

Ronnie McMi.llian

Permissiolls k;sociate

Mary Jaine Wjnokur

AtcOlmJ(ng Managef

Ronald 'P. era.nston

AC(J'ounJing Assistarlt

Azal ia St'ephenS

SYMPOSIUM

A QUARTERLY JOURNAL IN MODERN LITERATURES

VOLUME 57 NUMBER 2 SUMMER 2003

A Reappraisal of the ''Total'' Novel: Totality and Communicative

Systems in Carlos Fuentes's Terra Nostra

Mark Anderson

Carlos Puentes 's monumental novel Terra Nostra ( 1975) is often described as a

"total" or "encyclopedic" novel. One way that this novel creates the illusion of

totality is through the manipulation of communicative systems. By creating a

Hagelian dialectic between opposing di scourses in a wide variety of media,

Terra Noslra stimulates the reader to arrive at a synthetic understanding of

power relations. However, this synthesis is also directly written into the text,

thus raising questions about the autonomy of the process.

La re-creaci6n del romanticismo en La Reina de las Nieves de

Martin Gaite

Nuria Cruz-Cdmara

La Reina de la.\' Nieves (1994) by Carmen Martin Gaite rearticulates central

romantic themes from a femini st perspective. The masculinist aspects of the

romantic self are el iminated to create an ideal symbol of gender integration, the

androgyne, which becomes the embodiment or new identities, free from gender

prescriptions.

L'adolescence devant la mort dans les oeuvres de Camus et

de Sartre

Vincent Gregoire

The theme of adolescence is rarely treated in twentieth-century French litera

ture. Camus' s and Same' s works are no different, except in the case of an

imprisonment ending before a flring squard. This article addresses issues such

as misunderstanding, bad faith, and betrayal faced by adolescents in Sarrre's

"Le MlIr" and Morts sans sepultures, and Camus 's Lellres (/ lin ami al/emand.

'"

Reviews

Vernon A. Chamberlin. "The Perils of Interpreting Fortunata's

Dream" and Other Studies in Gald6s: 1961-2002.

James C. Courtad

Louise McReynolds and Joan Neuberger, eds. Imitations of Life:

Two Centuries of Melodrama in Russia.

Erika Haber

59

81

93

107

109

MARK ANDERSON

SYMPOSIUM

QUARTERLY JOURNAL IN MODERN LITERATURES

A REAPPRAISAL OF THE "TOTAL" NOVEL:

Symposium (ISSN 0039-7709) is published

qu. arterly by Heldref Publications, 1319 Eigh

teenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036

1802. Heldref publications is the educational

publishing division of the Helen Dwight Reid

Educational Foundation, a nonprofit 50 I (c)(3)

organization, Jeane J. Kirkpatrick,

president, (202) 296-6267; fax (202) 296

5 1 49. Heldref publications is the operational

division of the foundation, which seeks to ful

fill an educational and charitable mission

through the publication of educational jour

nals and magazines. Any contributions to the

fo undation are tax deductible and will go to

su PPOrl the publications.

Periodicals postage paid at Washington,

DC, and at additional mailing offices. POST

M ASTER: Send address changes to Sympo

sium, Heldref Publications, 1319 Eighteenth

Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036-1802.

The annual subscription rate is $99.00 for

institutions and $47.00 for individuals. Single

coPy price is $24.75. Add $14 for subscriptions

outside the U.S. Allow six weeks for shipment of

first copy. Foreign subscriptions must be paid in

U_S. currency. For subscription orders and CllS

tomer service inquiries only, call 1-800-365

9753. Claims for missing issues made within six

months will be serviced free of charge.

Copyright 2003 Helen Dwight Reid Edu

cational Foundation. Copyright is retained by

the author where noted.

Contact Heldref Publications for copyright

permission, or contact the authors if they retain

copyright. For permission to photocopy He!

dref-copyrighted items for classroom use, con

tact the Copyright Clearance Cent.er (CCC),

Academic Permissions Service, (978) 750

8400. Copyright Clearance Center (CCC)-reg

istered users should contact the Transactional

Reponing Service.

Symposium is indexed. scanned or abstract

ed in the Arts and Humanities Citation Index,

Current Contents/Arts & Humanities. Human

ities Index, Research Alert, and Social Plan

ning/Policy & Development Abstracts.

Symposium does not accept responsibility

for views expressed in articles, reviews. and

other contributions that appear in its pages. It

provides opportunities for the publication of

materials that may represent divergent ideas,

judgments, and opinions.

TOTALITY AND COMMUNICATIVE SYSTEMS IN

CARLOS FUENTES'S TERRA NOSTRA

OF THE NUMEROUS LENGTHY AND COMPLEX NOVELS written by Mexican authors

in recent decades, Carlos Fuentes's Terra Nostra (1975) is the longest and

generally considered one of the most complex. This novel is Fuentes's most

exhaustive exploration of the origins of Mexican culture. Through a symbol

ic rewriting of history from the Conquest up through the present, Fuentes pre

sents a global vision of the roots of modern Mexican society. The novel's

panoramic scope defies facile summarization. In the broadest of terms, Terra

Nostra is divided into three parts that correspond to three overlapping geo

graphic and cultural spaces.

The first part, "EI Viejo Mundo," deals with shifting power relations as six

teenth-century Spain experienced the transition from a feudal society toward

an emerging capitalism. The central figure in this section, Felipe or simply "EI

Senor," is a composite figure of several sixteenth- and sevenleenth-century

Spanish monarchs. This character, obsessed with monologic political and reli

gious discourse, is placed in opposition to a socially and racially diverse group

that attempts to undermine his control through a discourse of plurality. The

second section, "EI Mundo Nuevo," explores the Americas as exotic otherness

as well as a blank site for the construction of cont1icting European utopias .

Two Spaniards, self-exiled for political reasons, are the first Europeans to

arrive at the shores of the New World. Pedro, a dispossessed farm laborer and

sailor, immediately claims a piece of the land for himself by fencing it otT. As

the concept of private property is foreign to the indigenous groups who inhab

it the coast, he is eventually killed for his refusal to take down the fence. In

contrast, his companion, "EI Peregrino," is integrated into the indigenoLls cul

ture as the reincarnation of the Mesoamerican god Quetzaicoatl and makes a

symbolic dream journey to Tenochtitlan in which he undergoes a series of

tests that lead to a final confrontation with his double, "EI Espejo Humeante."

The third and final section, "EI Otro Mundo," represents the collision of

these two worlds and the ensuing formation of a hybrid mestizo culture that,

interestingly, has its center in Paris. However, the hybridization of the two

worlds is not shown to be the final victory of plurality over monologism.

Through the temporal juxtaposition of scenes that highlight power relations

from Roman times through the year 2000 (nearly twenty-tive years after the

59

61

Summer 2UUJ

SYMPOSIUM

6()

pL1 blication of the novel) and the reincarnation of characters from earlier time

pe-riods, the novel portrays power relations not as a simple binomial opposition

bLI- t as a constantly oscillating pendulum that reaches critical mass in Paris on

toe eve of the third millennium. The resulting apocalypse leaves only Polo

the reincarnation of "El Peregrino," and the reincarnated La Celestina

alive as the Edenic pair who may generate a new beginning for the human race.

The scope and density of Terra Nostra have elicited a wide gamut of

from scholars and critics, ranging from "a sprawling, encyclopedic

rO- cnster" (Brashear 1 0 1) to "novela monumental" (Marquez Rodriguez 185);

fc

om

the product of "una ambicion ilimitada" and "un proposito totalizador"

(Goytisolo 237) to "palimpsest" and "roman gourmand" (Price 48). Roberto

Gcnzalez Echevarria has written that "Fuentes' voluminous novel represents a

considerable effort to achieve an absolute knowledge of Hispanic culture" (89),

wbereas Lucille Kerr describes Terra Nostra as "Fuentes' attempt to write a

'1:o

t

a1' and 'eternal' novel" (99). Indeed, two rubrics surface time and again in

the critical discourse on this novel, like mantras to complement Fuentes's rnan

clala: the concept of the "total" novel and its synonym, the "encyclopedic"

aovel. I However, these terms are rarely qualified by their users.

Tbe Theory of the Total Novel

According to one critic, "The term 'totalizadora' apparently derives from

sociology where it first came into vogue in Latin America. The idea is that

subjects of study need to be seen in their 'totality'-almost a.Renaissance

man's intellectual approach" (Brashear 102). This perception of society as an

'.organic" whole can be traced to Auguste Comte's formulation of positivism,

a theory that became popular in Latin America during the late nineteenth cen

tury.2 However, it was not until the 1960s that the denomination novela total "' .

izadora, or "total" novel, surfaced in Spanish American letters, along with the

authors of the Boom. During this period, writers such as Alejo Carpentier,

Julio Cortazar, Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Gabriel Garcia

1'1arquez published a series of essays and novels in an attempt to redefine the

parameters of the novelistic tradition in Latin America. Among these writings

was Vargas Llosa's critical introduction to loanet Martorell's Tirant 10 Blanc

( L 969), where he articulates the beginnings of a theory of the total novel, in

which the novelist supplants or displaces God by creating an autonomous fic

tional world capable of competing with exterior reality. According to the Peru

vian novelist, Martorell begins this tradition of fictive creation in his chivalric

ncvel Tirant 10 Blanc: "Martorell es el primero de esa estirpe de suplantadores

de Dios-Fielding, Balzac, Dickens, Flaubert, Tolstoi, loyce, Faulkner-que

pretenden crear en sus novelas una'realidad total,' el mas remoto caso de nov

elista todopoderoso, desinteresado, omnisciente y ubicuo" (11). Novelists

assume the role of God within the fictional world, exercising complete con-

Anderson SYMPOSIUM

trol over their tictional creations. However, the author of a novel does not live

in a vacuum, and this fictional "total reality" is not constructed from nothing

ness. Rather, the referents that form the fictional world reflect the world out

side the novel. The act of creation lies in constructing a novelistic system from

a preexisting set of elements: "El novelista crea a partir de algo ; el novelista

total , ese voraz, crea a partir de todo" (29). Consequently, for Vargas Llosa,

this "totalizing impulse" is closely linked to the representation and mediation

of reality, even if the constructed world of the novel is synthetic and ultimately

parodic of its modeL Yet he is acutely aware of the essential superficiality of

this representation and its ultimate fictional or illusory nature:

La representacion de la realidad total que puede dar una novela es ilu

soria, un espejismo: cualitativamente identical, es cuuntitativamente una

infima particular imperceptible confrontada al infinito vertigo que la

inspira. Da la impresion de ser un caos tan vasto como el real, pero no

es ese caos; representa la realidad porque tomo de ella todos los aromos

de su ser, pero no es esa realidad. (33)

Within the confines of the novel, exterior reality becomes subordinated to the

interior, fictional reality of the novel. The exogenous elements that both con

stitute the fictional world and reach outward from it, bringing to bear entire

fields of knowledge that are directly or indirectly related to them in the com

plex system of reality, confer a deceptive sense of legitimacy to the fictional

world. These referents have a centripetal effect, concentrating spheres of

information from far beyond the limits of the novel. However, the structuring

of these elements within the novel is never the same as in reality (as much as

it may wish to imitate it); this is how the novel gives the impression of being

the "chaos" of totality, without being totality itself.3

In his essay La nueva novela hispanownericana (1969), Fuentes employs

Vargas Llosa's terminology of the total novel in his analysis of several con

temporary Latin American works, including Vargas Llosa's own Lil Cilsa verde

(1966). According to Fuentes, the modern novel is epitomized in the totaliz

ing tradition of authors such as Faulkner, Lowry, Broch, and Golding

[quienes] crearon una convenci6n representativa de la realidad que pre

tende ser totalizante en cuanto inventa una segunda realidad paralela,

finalmente, un espacio para 10 real, a traves de un mito en el que se puede

reconocer tanto la mitad oculta, pero no por ello men os verdadera, de la

vida, como el significado y la unidad del tiempo disperso. (19)

If Vargas Llosa associates the total novel with realism in literature, Fuentes

highlights the importance of myth.

4

For Fuentes, myth and reality are insepa

rable. One cannot exist without the other, even if myth is habitually subsumed

to reality. Consequently, he writes that "solo la palabra vertida puededescol

oral' eso que pas a pOl' 'realidad' para mostrarnos 10 real: 10 que la 'realida,d'

Summer 2003

6::2 SYMPOSIUM

c; onsagrada oculta: la totalidad escondida 0 mutilada por la l6gica conven

c;i.onal (por no decir: de convenci6n)" (85). Fuentes, then, sees myth as a con

s. tituent of totality. Fuentes's reinstatement of myth as a structural component

o:f the novel reveals a crisis in realism that the total novel attempts to address

bY including parts of reality that are masked or "mutilated" (to use Fuentes's

plJrase) by conventional logic.

Working with elements delineated by Vargas Llosa and Fuentes, Robin W.

piddian has generated a provisional list of tendencies that he considers com

LXlon to total novels.

s

Fiddian's addition to Vargas Llosa's and Fuentes's con

tributions is his analysis of language, informed by Severo Sarduy's influential

s;t:udy of the Latin American neobaroque literary style.

6

Indeed, the use of a

'baroque" verbal texture and the "paradigmatic overspill" are symptomatic in

the fiction of these authors. The baroque surface of these novels, in fact,

results from the sheer number of linguistic and cultural referents that occur

"""ithin them, and the "paradigmatic overspill" perceived by the reader can

often be attributed to the presence of heteroglossia as well as to the theoreti

c al interests of their authors. The excesses of these novels are not limited to

their authors' aesthetic preferences; rather the referential overload is neces

sary to evoke the connection with totality in the mind of the reader.

7

'The Encyclopedic Novel

The marking of the encyclopedia as a metaphor for the construction of cos

:o1ography by Jorge Luis Borges in "TWn, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" hits the nail

on its head. Few objects more aptly symbolize a world view in which all

lcnowledge is perceived as immanently catalogable and leads to a unified,

absolute system or truth. It is not surprising that totalizing novels such as .

... .

Joyce's Ulysses, Del Paso' s Palinuro de Mexico, and Pynchon's I Gravity's

Rainbow have often been described by critics as "encyclopedic narrative." In

{act, Vargas Llosa's and Fuentes's delineations of the total novel find a paral

lel expression in the concepts of the encyclopedic novel articulated by Edward

Mendelson and Mexican novelist Gustavo Sainz. Sainz provides the follow

j:ng definition:

Encyclopedic narrative attempts to put in perspective the totality of

knowledge and beliefs of a nation's culture and, at the same time, to

identify the ideological perspectives to which that culture conforms and

by which it interprets its knowledge. Keeping in mind that it is a prod

uct of an epoch in which human knowledge is greater than any single

person is able to master, it necessarily makes frequent use of synec

doche. No one encyclopedic narrative can encompass all the natural sci

ences, so one or two serve to represent the entire spectrum of scientific

learning. (570)

Anderson

SYMPOSIUM 63

Sainz's definition of encyclopedic narrative articulates three fundamental

points. First, it defines the relation of the encyclopedic novel to reality in

terms of Hegelian totality (parts to the whole). Second, it recognizes that this

relation functions on a basic mechanism of metonymical or synecdochal asso

ciation. Third, it inscribes the encyclopedic novel within a national context

and underscores the critical relationship that total novels develop with respect

to their cultures' ideological coding.

Mendelson coincides with Sainz's delineation of encyclopedic narrative,

stating that "all encyclopedic narratives [ ...Jare metonymic compendia of the

data, both scientific and aesthetic, valued by their culture. They attempt to

incorporate representative elements of all the varieties of knowledge their soci

eties put to use" (9). It is significant that Mendelson associates encyclopedic

narrative with indicators of a certain moment in which national cultures begin

to recognize their uniqueness (10). For Mendelson, encyclopedic narrative per

forms a role in the construction of national identity. This statement is particu

larly engaging in the context of Latin American narrative, especially when one

considers that most of the truly encyclopedic works of narrative in the Latin

American tradition begin appearing around the mid-twentieth century.s

Hegelian Dialectics and the Total Novel

Precursors such as Don Quixote, Tristam Shandy, and several other early

novels clearly demonstrate totalizing tendencies. However, modern total nov

els such as Terra Nostra consciously deploy a Hegelian conceptualization of

totality in their attempt to capture the complexity of reality. Indeed, Arnold

Hauser has suggested that modern art in general IS characterized by a "mania

for totality" (237). That mania is rooted in the revolution of scientific and

philosophical thought of the two preceding centuries and more specifically in

Hegel's writings Y As Sainz pointed out, encyclopedic novels operate on a

basic synecdochical relation of the parts to the whole. a relation developed by

Hegel in his dialectical method.

Hegel is particularly concerned with the formation of an individual con

sciousness that is equipped to conceive totality. His model of consciousness

postulates an "absolute" or "universal truth," which is at the same time the

underlying essence and the irreducible totality of all things. The perception of

this totality requires a shift in scale from "finite spirit" to "infinite spirit" (Intro

duction 33). However, he writes, "we have on hand for the essentially specula

tive nature of the Absolute only finite materials which are all that can serve us

to comprehend and express the nature and character of the infinite, whether in

a wholly literal or also symbolic sense" (33). The total. infinite nature of reali

ty, then, can only be inferred through the observation of its tinite parts.

In his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, Hegel further explores

the relations between "das Ganze" (the whole) and "die Teile" (the parts). He

6- 4 SYMPOSIUM Summer 2003

observes that as a system, the "parts" can only be understood as a "whole." In

other words, the parts make no sense if they are taken out of context. The con

text, or web of interrelations between the parts, coalesces a meaning that the

parts themselves cannot individually signify. For Hegel, isolated parts are

abstract entities that can only be understood subjectively without the objecti

fying influence of the context or system to which they belong. The subjective

act of perceiving these parts only attains objectivity through the context of

totality. Yet, because of the finite nature of human perception, a consciousness

of totality can only be reached through the contemplation of the parts, which

are also finite and therefore can be perceived directly. Because these parts

simultaneously constitute the system, they also conceal the keys to its dis

cernment. The systematic relations that govern the whole may be discovered

in the play between opposing parts or binomial oppositions. The whole is thus

inferred from the parts by discovering the dialectical movement that exists

between them. Furthermore, each part contains dialectical elements evocative

of other systems within itself. In this way, the parts are autonomous and rep

resentative of the whole themselves.

Lukacs has argued that the novel has been a "totalizing" genre from the

:llloment of its inception. 10 Lukacs, following Hegel, associates the self-reflex

i vity that characterizes the novel as a genre with the perception of the parts in

relation to totality:

Thus a new perspective of life is reached on an entirely new basis-that

of the indissoluble connection between the relative independence of the

parts and their attachment to the whole. But the parts, despite this attach

ment, can never lose their inexorable, abstract self-dependence; and their

relationship to the totality, although it approximates as closely as possi

ble to an organic one, is nevertheless not a true-born organic relationship

but a conceptual one which is abolished again and again. (75-76)

Addressing the "inner form" of the novel, Lukacs distinguishes between a

conceptual and a "true-born organic" relationship between the parts and the

system to which they pertain. A more accurate term, "referents," may be sub

stituted here for "parts" to highlight the relation of the novel as a conceptual

totality to the real world as an epistemological or factual totality and the fact

that referents in the novel are a symbolic presence, functioning by metonymy.

Referents work within the novel to evoke fields of information that are exoge

nous to the novel. Consequently, Lukacs places much emphasis on the alle

gorical nature of the novel. 1 1 He establishes a conceptual connection between

referents in the novel and the exterior world: the novel is a space in which the

"system of regulative ideas that constitutes totality" becomes visible (81). He

further asserts that "the outside world cannot be represented" because, by def

inition, transcribing totality is impossible and therefore any attempt to repre

sent it becomes subjective (79). Only the systematic relations between sub-

Anderson SYMPOSIUM 65

jects and objects within totality can be objecti vely portrayed in the novel. For

Lukacs, the novel's relation with the totality of reality is thus based on the

inclusion of social, cultural, and historical components that invoke the sys

tematic relations that exist within it. Terra Nostra, like other total novels, con

sciously exploits this model of totality in an attempt to acti vate the reader to

the perception of these systematic relations, which for Hegel constitute the

"Absolute" and must be inferred through the dialectic method.

12

The Dialectics of Communication in Terra Nostra

Several critics have amply demonstrated the vastness of the cultural and

historical knowledge that underpins Terra Nostra and the interwoven, syn

thetic nature of the social, cultural, and historical referents that appear in it.

13

The dialectical relations between these real world referents work to create a

system within the novel that imitates and at the same time supplants exterior

reality, negating its model. Simultaneously, a dialectic forms among the his

torical object, the group of texts that constitute the historical irnagination, and

the fictional creation that requires the reader to arrive at a resolution. Howev

er, the interplay within the vast field of referents included in Terra Nostra does

not completely account for its effect on the reader. A significant factor is

Bakhtin's concept of dialogism. Bakhtin builds from Lukacs's model, but he

disagrees with Lukacs's assertion that the novel's relationship to totality is

purely conceptual. 14 He recognizes that the novel as a textual construction is

created primarily from language and that all language bears an ideological

load that cannot be stripped away. Indeed, for Bakhtin, "form and content in

discourse are one, once we understand that verbal discourse is a social phe

nomenon-social throughout its entire range and in each and every of its fac

tors, from the sound image to the furthest reaches of abstract meaning" (251).

Bakhtin deflates and concretes the metaphysical component of Lukacs's

vision of totality (which he had inherited from Hegel). He does not, however,

discard the term itself. Rather, totality, like language, becomes a concrete

social phenomenon that is reflected in the system of languages in the text:

"The novel orchestrates all its themes, the totality of the world of objects and

ideas depicted and expressed in it, by means of the social diversity of speech

types and by the differing individual voices that flourish under such condi

tions" (263). Lukacs's "parts," or referents, become heteroglossia in Bakhtin;

the invocation of the whole now functions through a concrete system of

socially diverse languages rather than an abstract system of objects. Through

the presence of heteroglossia, the novel becomes a microcosm of the society

to which it pertains. Totality is thus represented through the inclusion of social

heteroglossia in the text, which results in the dialogic nature of the novel.

According to Bakhtin, this polyphony creates the multiple, conflictive points

of view that allow for the utilization of Hegel's dialectic method to infer the

66 SYMPOSIUM

Summer 2003

t:otality of social stratification within a society. The novel, then, becomes an

encyclopedia of languages that captures the totality of an era's heteroglossia.

7erra Nostra capitalizes on this multiplicity of discourses to create the impres

sion of what Corral calls a "collectivizing of subjectivities" (319), a web of

i-ndividual discourses that form an objective system through a complex

process of counterpoint and juxtaposition of subjective modes of expression.

Communication is one system in Terra Nostra that is configured to create

a polyphonic sense of totality in the mind of the reader through the use of

dialectically opposed subjectivities. The self-conscious orchestration of sev

eral levels of communication in Terra Nostra relies on basic organizing and

structural principles of metonymical and synecdochical association. The novel

invites the reader to analyze the roles of written, spoken, and nonverbal com

munication by creating dialectic systems that appear in the fissures of the

mimetic or rhetorical representation of communication as a total system with

in a social context. The systems themselves are also directly textualized; char

acters and narrators alike demonstrate reflexivity about their own discourse

and an awareness of their textuality that transcends the borders of their fic

tional world. On the extradiegetic level, Fuentes explores the relationship

between author and reader as well as between one text and the system of texts

to which it pertains. Within the limits of the text, both the narrators and char

acters show themselves to be conscious of the textuality of their discourse(s)

and of the ultimate verbal (and communicative) economy in which all their

transactions take place. Through the inclusion of a wide range of commu

nicative components and elements of verbal and nonverbal communication,

Fuentes evokes a sense of polyphonic totality in the mind of the reader.

"Verbal Communication

...

The use of verbal communication in Terra Nostra hinges on three distinct

considerations: language as power, reflexive writing (metafiction), and the use

of linguistic multiplicity as a symbol of cultural and religious plurality. Each

of these considerations represents the resolution of a dialectic opposition that

jIl tum leads to a general synthesis in which power relations emerge as a cen

tral organizing principle in the novel.

In Terra Nostra, the conflation of discourse and power is a central thematic

concern (Kerr 96). Fuentes's fantastic rewriting of history can hardly be con

s trued as realism. Instead, it directs the reader toward a critical re-evaluation of

history and the power relations that propel it. The repressive authoritarian and

<::entralized power that Felipe and his "texto unico" represent are in a constant

:5 truggle for the control of discourse against the decentralization and plurality

that Ludovico, Celestina, Fray Julian, EI Cronista, and others embody as a

<::ollective threat to homogeneity. In Felipe's world, power is based on the pos

session of this "texto unico" that "asegura la perrnanencia y la legitimidad de

' Anderson SYMPOSIUM 67

los actos del poder" (194). But for Felipe, the constitutive power of the text

extends beyond the physical plane. The text is capable of prefiguring reality,

as he tells Guzman: "Escribe: nada existe realmente si no es consignado al

papel" (111). Felipe's "one text" is also associated with truth: "Escribe,

Guzman, escribe, 10 escrito permanece, 10 escrito es verdad en sf porque no se

Ie puede someter a la prueba de la verdad ni a comprobaci6n alguna [ .. .]"

(193). Felipe's statement echoes Fuentes's ideas on the nature of the total

novel. Writing in general, and particularl y fiction, is inherently truthful

because it uncovers that "masked" part of reality that cannot readil y be per

ceived because of societal conventions.

However, the Cronista counters Felipe's assertion: "Mi rad asf el misterio

de cuanto queda escrito 0 pintado, que mientras mas imaginario es, por mas

verdadero se Ie tiene" (240). The Cronista refutes Felipe's claims that his text

has the power to constitute truth and reality by alluding to Cervantes's ques

tioning of legitimacy in Don Quixote. Felipe' s doubt s regarding the validity of

his discourse also undermine the claims he makes for hi s text: "i, Tu nunca

dudas, Guzman, a ti nunca se te acerca un demonio que te dice, no fue asf, no

fue s610 asf, pudo ser asf pero tambien de mil maneras diferentes, depende de

quien 10 cuenta, depende de quien 10 vio y c6mo 10 vio?" (194). Felipe ques

tions the unity of his text, of his history, and of the transmission of history in

general. These moments of self-doubt are the space in which appear what

Foucault terms "systems of exclusion" and the institutions that they defend.

Both Felipe's doubts and the Croni sta's dissenting voice are silenced by these

systems of exclusion. The agent of the silencing is the Inquisition , and in both

cases the characters are forcefully isolated from ,society. In the scene immedi

ately following Felipe's voicing of his doubts, Guzman drugs him and

attempts to betray him to the Inquisition by turning the "testamento" contain

ing his heretical ravings over to Fray Julian. It is significant that "testamento"

is a polysemic word that evokes both the rites of succession and the tran

scription of the revelations that Felipe has witnessed. Felipe's testament is

threatening in that it denies the succession of power and because it gives voice

to the possibility of plurality. Guzman's betrayal is therefore a political act

that both subverts and reinforces the centers of power: he takes revenge on his

despised master and at the same time protects the status quo. Guzman acts as

the agent of the institution of nobility that struggles to conserve its power, or

rather regain that which it has lost. Felipe is only saved by the intervention of

Fray Toribio, who burns the evidence. In any case, the shadowy, neurotically

totalitarian side of Felipe's personality has already isolated him from society:

he has locked himself into the seemingl y impenetrable EI Escorial. The Cro

nista is also silenced, condemned to the galleys, after he is betrayed to the

Inquisition by his friend, Fray Julian. The church, like the nobility, must also

toil to conserve its power and the uniqueness of its text.

Related to the ties between power and the text, meditations on the function

vo Summer 2003

and uses of writing are an important thematic consideration in Terra Nostra .

The narrators show awareness of the act of narration as communication.

Celestina, apparently speaking to the Naufrago, catches the attention of the

reader with statements such as this: "Quiero que oigas mi cuento. Escucha.

Escucho y veo por ti" (65). This passage certainly seems an apt description of

the narrator's position in relation to her listeners: to hear and see for us. The

reader is drawn into the novel through the use of pronouns in the second per

son; the characters, directly or indirectly, appear to be speaking to us. Teodoro

also appears to address himself to an extratextual reader in the parchment from

the second green bottle: "Yo, Teodoro, el narrador de estos hechos, he pasado

la noche reflexionando sobre ellos, escribiendolos en los papeles que tienes 0

algun dla tendnis entre tus manos, lector, y considenindome a m! mismo como

otra persona: tercer a persona de la narraci6n objetiva; segunda persona de la

narraci6n subjetiva" (691). The narrator, by showi ng his awareness of an audi

ence as well as admitting his manipulation of voices, creates a disruption in the

complex layering of narrative levels in which he performs a metalepsis. By

directing himself to an unspecified reader, he communicates anachronically,

through time, on the mimetic level to reach characters in the distant future of

his world and through narrative distance on the diegetic level to reach the

implied reader of the novel. He thus communicates simultaneously within and

outside of the narrative structure of the novel. In this way, the dialectic fic

tion/reality is stressed, requiring a synthetic resolution from the reader.

The inclusion of all three voices of the triad of personal pronouns is anoth

er way in which Fuentes uses dialectics to represent the totality of communi

cation and simultaneously emphasizes its hierarchical nature. As Barthes has

stated, a polarity exists between personal pronouns that "involves neither

equality nor symmetry: I always has a position of transcendence with respect

to thou, I being interior to the enonce and thou remaining exterior to it; how

ever, I and thou are reversible-I can always become thou and vice-versa" (45).

However, "this is not true of the non-person (he or it), which can never reverse

itself into person or vice-versa," as "he is situated outside discourse" (45). Nar

ration in the second person "tL'" voice is inclusive, and narration in the first

person "yo" presupposes a listener who may reverse the order of communica

tion, while narration in the third person automatically precludes interaction in

the discourse, effectively negating any possibility of agency other than that of

the speaker. In thi s sense, third-person narration is hermetic, for it is closed dis

course. In Terra Nostra, Fuentes avails himself of these distinctions to elabo

rate the hierarchy of power and discourse. The narration that focalizes on

Felipe is written in third person. Felipe's desire for absolute control is mirrored

in the closed nature of the narration. Although the distance between character

and narrator sometimes wanes, the narrator always maintains tight control over

the discourse. When the narrator gets too close to the character, satirical lan

guage is used to re-establish distance. In contrast, the sections that deal with

characters and narrators that represent plurality (Celestina, Ludovico, el

Naufrago) tend to be narrated in first or second person, thus opening the di s

course to the possibility of interpersonal communication. These sections seem

to invite the participation of both characters, who may interrupt the narration,

and readers, who are drawn closer to the speaker. This polarization is further

illustrated in the presence of fictionalized listeners in the novel : Felipe's inter

locutors are often mirror images of himself (his conversations with his dog,

Bocanegra, with paintings, or with actual mirrors), denoting an interiorized,

circular system in which he is both the sender and the receiver of his message.

In contrast, the representatives of plurality often speak toward the exterior, to

other, different humans. The monologic nature of Felipe's di scourse is thus

contrasted with the dialogic exchange of his adversaries. This dialectic opposi

tion further develops the systems of power present in the novel.

Parallel to the manipulation of the triad of personal pronouns, Fuentes cre

ates an opposition between Felipe's language and desire for homogenous dis

course and the plurality of voices and linguistic diversity represented by other

characters and narrators. The interruption of these voices at both the mimetic

and diegetic levels can be read as heteroglossia. Fuentes consciollsly uses this

technique to represent the struggle for power at the linguistic level. The fol

lowing vocabulary of exclusion is employed by the side of closed, mono logic

order: "marrano converso," "falso cristiano," "judaizante vero," "hereje judaf

co," and so on (Terra Nostra 68). A rhetoric of inclusion and plurality is

placed in opposition to this vocabulary and spoken by its proponents. Ludovi

co describes this second, heterogeneous group: "Mas alia de las l1lurallas de

tu necr6polis y de su severa fachada de unidad, Felipe, otra Espana se ha ges

tado, lIna Espana antigua, original y variada, obm de muchas culturas, plurales

aspiraciones y distintas lecturas de un solo libro [ ...J" (624). Ludovico's

Spain is a decentered Spain of linguistic and cultural ditlerence that contrasts

with Felipe's totalitarian views, symbolized in the monolithic EI Escorial.

Self-conscious intertextuality forms the bedrock of the narrative structure

of Terra Nostra . Throughout the novel, Fuentes works against the genealogy

of influence that critics such as Harold Bloom propose. 15 Rather than a sim

ple acknowledgment or agonistic effacement of his models, he performs a

self-conscious Borgesian creation of his precursors. 16 Using a series of liter

ary referents and borrowing characters from other sources, Fuentes actively

manipulates what Barthes calls the circular memory of reading. The reader's

memory of the texts cited is challenged by the mutation that these texts under

go in Fuentes's rewriting . In addition, he engages in an appropriation and

transformation of the three most prominent archetypes of Spani sh literature:

Don Quixote, Don Juan, and La Celestina. By invoking these characters and

then erasing the readers' expectations of them, Fuentes willingly negates the

presence in his text of the authors of hi s pre-texts. Except in the case of Cer

vantes, who is transmogrified into another archetypal tigure, the Cronista, the

I V t....J .l. .1." '-J\J ....,J.".L ....

authors of these texts are not invoked and the characters themselves are trans

formed. By removing the authorial presence and authority, the origin and the

unity of meaning in these texts is removed and left open to revision and muta

tion. Fuentes effaces the points of cohesion in these texts, cutting the bonds

that hold them to a fixed interpretation or meaning, thereby granting the char

acters certain autonomy from their creators. In this way, the reader is forced

to create a synthetic character that mediates between Fuentes's mutated arche

types and the original, a process that requires a critical consciousness with

respect to their role in Hispanic culture.

Nonverbal Communication

In Terra Nostra, Fuentes both describes nonverbal behavior and expands its

communicative capacities. As linguists such as Fernando Poyatos have point

ed out, gesture, or "kinesics," is an integral part of communicative systems.

Other body parts are often as responsible for the transmission of meaning as

the tongue. In Terra Nostra, gesture plays a central role in the performance of

power: the language of power is as much action as verb. The kind of gesture

that Ekman and Friesen (71) have termed "emblems," or those signs that are

acted out consciously by a speaker and have a fixed meaning within a cultur

al context, is particularly effective for the communication of hierarchy and

power, as is evident in this passage:

El hombre del bigote trenzado tom6 el pelo del naufrago con un puno y

levant6 violentamente la cabeza prisionera: la mirada opaca del joven se

fij6 en el gesto impaciente de la cabeza de la mujer, enmarcada por las

altas alas blancas de una gola. [ ...J La mujer levant6 un brazo de man

gas abombadas y dijo, al tiempo que con el dedo fndice ordenaba a la

guardia de negros: -T6menlo. (Terra Nostra 45)

This fragment contains a broad range of symbolism and gesture that not only

complements the command at the end but effectively defines it. In the first

sentence, the guard takes the prisoner by the hair with his ','puno." The

clenched fist is a universal symbol of force, an emblematic sign that commu

nicates aggressiveness and a threat of violence to the person to whom it is

directed. This use of "puno" is complemented by the adverb "violentamente"

later in the sentence. The Naufrago is placed in a low, subjected, and ulti

mately powerless position, which is contrasted to that of the Queen Mother,

who looks down on him and orders with the impatience of authority. It is note

worthy that the narrator does not describe her gesture; rather, he captures its

essence, the impatience. In the second sentence, her raised arm coincides with

the fist of the guard as a display of power that culminates in the order:

"T6menlo." Here a sequence of emblematic gestures demonstrates a hierarchy

of power in which a person in a position of authority communicates her power

through intermediaries, leading up to the final verbal expression of that

power: the order.

Emblems are also used to contradict the discourse of power. Such is the

case in this paragraph:

Desde su posici6n arrodillada, Guzman, allevantar la mirada para entregar

el brevi ari 0, mir6 tijamente, por un instante, al Senor y debi6 arquear las

cejas de una manera que ofendi6 al amo; pero este no podfa reprocharle a

su servidor la celeridad con que demostraba su obediencia y SLi respeto; el

acto visible era el del mas excelente vasallo, aunque la intenci6n secreta de

la mirada se prestase, mas que nada por indetinida, a interpretaciones que

el Senor, a un tiempo, deseaba admitir y rechazar. (46)

Guzman's apparently servile attitude toward his master (embodied by his

kneeling before him) is belied by one gesture: the arching of his eyebrows, an

emblem that reveals a questioning attitude. This emblem contrasts with other

signals by which the vassal communicates to his master "obedience and

respect." In this way, one ambiguous emblem is able to subvert an entire

sequence of signs that display servility.

The visual image also holds a privileged position in Terra Nostra. Howev

er, it is not always just what is seen that is important. Fuentes places great

emphasis on both who does the seeing and the transfer of information through

gaze. Mirar is one of the verbs that occur most frequently in the novel (Espina

57). Gaze provides unity both to the structure of the novel (it opens the first

chapter and closes each of the three sections) and as a shared perspective

between characters (Williams 94). Gaze can also confer power to another or

dissipate one's own power, as Felipe's father tells him: "Desele al mas por

diosero de los pordioseros de esta tierra de mendigos el menor signo de dis

..f:.. tinci6n, y en seguida se comportanl como un hidalgo vano y pretencioso; no

los distingas, hijo, ni con una mirada, es gente sin importancia" (43). Felipe

remembers his father's advice too late during his hunting trip, after glancing

angrily at his subordinates when they were too slow to react to his orders:

"Quizas, encaramados en la siena, recordaban al Senor que par un momento

se habla dignado de fulminarlos con una mirada, sin necesidad de hablarles ;

y si su padre tenia raz6n, de esa mirada nacerfa multiplicadas soberbias y

rebeliones" (43). Openly recognizing the existence of anyone not on his social

level opens channels of communication that threaten his power. It gives the

voiceless mass a voice, an individuality that breaks forth from the anonymity

of the collectively ignored. This idea is echoed by one of Felipe's hallucinat

ed Christs speaking about the Romans: 17

Yo agradecfa la ceguera del amo extranjero ante la raza extrana y

sometida, pues si nosotros sabemos distinguir el rostro de cada opresor

extranjero ya que en ello se nos va la vida, ellos nos miran como 10 que

somos: una masa de esclavos, sin fisonoinias individuales, cada uno

indistinguible delos demas. (208)

When Felipe breaks the social norm of not deigning to look at his subordi

nates, both parties undergo a psychological shift. The faceless mass suddenly

becomes a group of subjects capable of action rather than objects to be dis

posed of at his will.

Sex is an important medium for the communication of power in Terra Nos

tra as well. The text contains explicit heterosexual and homosexual sex acts

as well as incest, sadomasochism, bestiality, necrophilia, masturbation, and

abstinence. The communicative value of these acts varies according to their

context. In some cases, for example, heterosexual contact becomes a means to

communicate messages that are impossible to signify with words, such as

what occurs in one encounter between Celestina and the Naufrago (Terra Nos

tra 278). In these cases, sex acts acquire a verbal capacity superior to that of

dialogue itself. Likewise, abstinence from heterosexual sex often reflects an

absence of communication. Felipe's abstinence with respect to his wife, La

Senora, fits in perfectly with his fixation on immutability and isolation. As he

reveals in one moment: "[...J mi muerte absoluta, mi absoluta remisi6n a la

inexistencia, a la incomunicaci6n hermetic a con toda forma de vida; este es

mi proyecto secreto" (203). His sexual abstinence is thus closely linked to his

metaphysical project of total hermeticism.

Felipe's desire to be the last of his line and to achieve mystical nonexis

tence through abstinence contrasts with his father's animal sexuality. Felipe el

Hermoso uses sex to communicate his authority, to delimit the geographic and

human topography under his control. His violent animal sexuality is that of

the wolf: he fornicates almost unconsciously, making no distinction for social

class or even between humans and animals. Yet his conjugal relationship with

1>: ~

the Dama Loca also negates the possibility of communication through sex.

The Dama Loca explains: "A mf me tomaba a oscuras; a mf me tomaba para

procrear herederos; conmigo invocaba el ceremonial que veda todo deleite de

vista y de tacto" (74). With the senses denied their functions, the sex act

becomes mechanical and incommunicative.

Masturbation falls into the same category of noncommunication. Because it

is a self-contained discourse with no interlocutor, there can be no transmission

of a message. The Dama Loca, denied the possibility of a shared and meaning

ful sexual experience with her husband, becomes obsessed with his body after

his death. His death permanently closes the possibility of any communication

between them; she must resort to the interiorization of the sexual experience

through fantasizing, masturbation, and ultimately necrophilia. The pattern of

sexual repression and isolation leading to necrophilia continues in La Senora,

who fabricates several substitute lovers, the last of whom is a sort of Frankestein

pieced together from the body parts of Felipe's dead ancestors.

f U I U t : C ~ U I I ':)1 l"Jr'!.:l.1U1Y.l I.)

In contrast, homosexuality emerges as a form of resistance against

Felipe's absolutism. The bisexual Miguel de la Vida appears as a symbol of

tolerance: "AW vivfamos juntas todas las razas : mira mis ojos negros, viejo,

y mi rubia caballera. Soy dueno de todas las sangres" (252). Felipe orders

him to be burnt at the stake, because he represents a threat to Felipe person- .

ally, as his wife's lover, and on a political level , as a symbol of plurality

(racially, culturally, and sexually) that threatens Felipe's absolutism. Homo

sexuality also becomes entangled with religious heresy in one of Felipe's

delirious bouts of disbelief. Speaking of Christ, he muses that Hel dfa de su

bautizo que quizas s610 fue el dfa de sus nupcias sodomitas con Juan el

Bautista que quizas era un hombre que quiz8.s muri6, como el otro dfa muri6

el muchacho quemado aquf junto a las caballerizas, por sus amores nefandos

con el hijo del carpintero" (206). It is significant that Felipe places a moral

value on homosexuality. By applying the adjective "nefando," he classifies

homosexuality as deviant , unnatural, and ultimately evil. However, the "evil"

nature of homosexuality in this scene depends more on the heretical over

tones of the scene than the sexual act itself. For Felipe, homosexuality is pri

marily evil because it represents a threat to his absolutism.

Other forms of sexuality are used to illustrate the decadence and sterility of

the centers of power. In particular, the sex ual pleasure that Tiberio takes in both

hearing and viewing the pain of others is symbolic of the structures of politi

cal power that he has created. The fact that the actors in the orgies that he

directs are all in some way deformed also brings attention to the state of his

empire. Incest is another metaphor for the decadence of dynasty. La Senora's

incestuous relationship with her son fathered by Felipe el Hermoso, Johannes

Agrippa (who later becomes Don Juan), promotes a kind of sexual liberty that

rebels against the strict controls in place within El Escorial. Their relationship

also draws attention to the closed circuitry of Felipe's world. Although their

sex act as communication is not completely hermetic, its incestuous nature

places limits on the diffusion of the message: it is kept in the family.

More so than sex, physical violence as a communicative act is an intrinsi

cally coded behavior (Ekman and Friesen 69). Its action encodes its message:

it communicates itself directly without the mediation of words. Violence as a

communicative medium is intimately linked to power structures. Authority

maintains its power through the threat of violence, and the oppressed often

reject authority with a rhetoric of violence or violence itself. In Term NastY(!,

Felipe frequently answers challenges to his authority with violence. In fact,

the legitimacy of his power has been constructed on a base of physical vio

lence: young Felipe betrays his friends Celestina and Ludovico and the

Adamite movement they lead to consolidate his power, a move that results in

the slaughter of hundreds of people. His answer to heresy, which represents a

challenge to his "texto unico," is the same throughout the novel: after mas

sacring the Adamites, he lays siege to Rochelle and annihilates the Flemish

74 SYMPOSIUM Summer 2003

Protestants. Like the real-life, historical Spanish monarchs on which he is

modeled, Felipe silences difference by eliminating it.

Silence is perhaps a fitting topic to close thi s discussion of nonverbal com

munication. Two central manifestations of silence appear in Terra Nostra. The

first, fundamentally linked to with major thematic concerns of the novel, is the

silencing of social groups. There is the focus on the physical silencing of social

groups through the use of violence, intimidation, and simply ignoring them, as

was descri bed above. At the same time, Felipe's "texto unico," the written text

that embodies the official history, censures and silences any dissenting ver

sions. As Guzman states, "No es elsilencio el resorte de la autoridad del Senor,

sino la declaraci6n, el edicto, la ley escrita, la ordenanza, el estatuto, el pape\"

(273). Silence is the lot of the repressed, not those who hold the power and

therefore control the word. The absolute authority of the written text silences

all di ssonance. The power of writing to constitute and maintain reality is con

trasted with the fragility and temporality of the oral discourse of the unlettered

masses. However, oral discourse is shown to be more flexible than written dis

course, and orality infuses supposedly "fixed" or immutable texts. In this way,

Fuentes demonstrates the gap between rhetoric and social reality. Felipe's

authoritarian political language is ultimately ineffective before the oral reports

of the existence of the New World: he attempts to decree the nonexistence of

the New World in writing, but his attempts to silence the message brought by

the Peregrino are impotent. Through the manipulations of Guzman, who sees

his chance to avenge himself of his despised master, the discovery becomes

common knowledge. The silencing of social groups and di ssenting versions of

history support the global theme of power that underpins the text.

The second manifestation of silence in the novel is its use as a structuring

element. Silences or gaps in the narration that involve the reader in a process

of co-creation are integral to the construction of meaning (Iser 168-69).

Fuentes exploits the interplay between the implicit and the explicit in Terra

Nostra. Because of the omnivorous scope of the novel, its author resorts to a

fragmented structure in which only miniscule samples of explicit information

are presented, leaving sizeable gaps for the reader to fill in. Fuentes deals with

the immensity of the knowledge at hi s di sposal (after spending six years

researching the novel) by reducing forms to their lowest common denomina

tor. With the active reader's participation, one oblique referent can bring an

entire tield of concepts to bear on the interpretation of the novel. Williams has

provided an example: By setting a large section of Terra Nostra in EI Escori

aI, Fuentes evokes an entire tradition of Spanish religious architecture as well

as the political ramifications associated with such structures.

18

Thus, single

referents evoke larger constellations of information that the reader must

access from a common cultural background. Of course, if the reader is not

privy to the same cultural knowledge as the author, many of these referents

may pass unnoticed, and the scope of the novel is thus limited. .

Anderson SYMPOSIUM 7S

Conclusion

In Terra Nostra, systematic power relations are explored through a process

of representative selection of referents and social heteroglossia and the con

scious creation of a Hegelian dialectic between these elements. In this way, a

central locus of meaning is diffused throughout many different mediums that

are reassembled within the mind of the reader to create a total vision. One sys

tem that functions in such a way is communication: the dialectical represen

tation of both verbal and nonverbal communication in Terra Nostra creates an

autonomous fictional world within the mind of the reader that simultaneously

contends and interacts with reality. In other words, a dialectical sampling of

communicative elements leads the reader to arrive at a total vision of power

relations through a synthesis of the disparate verbal and nonverbal compo

nents that are represented.

,

The view of totality offered by Terra Nostra is necessarily limited cultur

ally, geographically, and ideologically, but the power relations and "human

values" it portrays are placed within a framework that models them as "uni

versal" OJ! "absolute."19 In this sense, Vargas L1osa's view that the total novel

ist assumes the role of God within the world of the novel becomes particular

ly provocative, especially when one examines how issues of legitimacy are

treated in this total novel. Ultimately, the role of the narrator in this novel, at

least at the highest level, is to be believed.

2o

The metanarrator, the compiler of

all the diverse narrating voices, is omniscient and as such holds the keys to

absolute truth. And, as Lyotard states, "God is not deceptive" (24). The mul

tiple voices that permeate the text coincide to reaffirm the legitimacy of the

synthetic meaning that is prefigured in the text under the control of this meta

narrator. Indeed, there can be little doubt that Terra Nostra contains multiple,

conflictive coding similar to that described by Carlos Alonso in his explo

ration of modernity in Latin American narrative. The sheer number of refer

ents in this novel and the transparency of its philosophical moorings are tes

tament to the critical discourse that surfaces through the narration, a critical

discourse repeated in Fuentes's companion essay Cervantes 0 la critica de la

lectura.

21

Likewise, thematic and semantic redundancy is the glue that main

tains cohesion within the extreme fragmentation of Terra Nostra's narration.

22

The ideological weight of Fuentes's critical discourse, together with the con

sensus historical perspective that opposes his fictional construction (as much

as that construction may undermine it), displaces the story line, which is then

forced into a supplemental position with respect to both history and theory. 23

The novel's critical apparatus promoting plurality and tolerance is thus at odds

with its own content; the insistence on its message ends up creating a unity or

centrality within the text that belies its own proposal. In other words,

Fuentes's critical discourse proposes "different readings of a single text"

(629), while at the same time enforcing a single reading through repetition.

24

76 SYMPOSIUM Summer 2003

In the end, the stress placed on ideol ogical content forces the reader to arrive

at a synthesis of dialecti cal opposites that has already been written into the

text by its author. This procedure undermines the autonomy of the parts that

is fundamental in Hegel' s method, thus putting into question the integrity of

the process, if not its conclusions.

University of California, Riverside

I. Fuentes comments on the mandalic structure of Terra NOSIra in an interview with Marce

lo Coddou. "Terra Nos/ro , 0 la critica de los cielos" 8.

2. Comtc's intluence on turn-of-the-century Latin American thought was pervasive in later

movements of national identity. as has heen well documented in works such as Leopoldo Zea's

El POsiTivim1O ,!II Mexico: Nacimiel/To, apogeo y decadencia (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Mexi

cana. 19(8) and Ahelardo Villegas's PoSiTivismo y /iorfirismo (Mexico: SEP, 1972).

J. It could hc argued that Vargas Liosa reformulates ideas proposed by Chilean poet Vicente

Huidohro decades earlier. Huidobro proclaimed in "Arte poetica" ( 1916) that "EI poeta es un

pequeno dios" and advocated a "totalizing" aesthetic in his manifesto "Total" ( 1932). Huidobro's

totalizing approach to poetry was not unique; Julien Benda, in his st udy of the French avant-garde

wi th which Huidohro was so intimately associated, states that "L' hymne 11 la totalite est une sorte

de lieu commun chel. tout un monde de litterateurs modernes" (48).

4. Although Vargas Llosa distinguishes a mythical component in TirO-ntlo Blanc, he does not

place the overarclling emphasis on myth that Fuentes does.

5. "I) The total novel aspires to represent an inexhaustible reality, and cultivates an encyclo

pedic range of references as a means towards that end. 2) The total novel is conceived as a self

contained system or microcosm of signification which accommodates ambiguity as a matter of

course. 3) The lotal novel is characterized by a fusion of mythical and historical perspectives, and

by a transgression of conventional norms of narrative economy. 4) The total novel displays a ver

bal texture that tends to the baroque, and typically exhibits paradigmatic overspiJl on to the syn

tagmatic axis of language" (Fiddian 33).

6. See Sarduy.

7. As Wilfrido Corral suggests in "Novel istas sin tim6n: Exceso y subjetividad en el concep

to de la novela total," total novels are characterized by an aesthetic of excess and an accumula

tion of suhiectivities. Howevcr, the techniques employed by these authors are not limited to a

purely aesthet ic function. They work to provoke a particular mode of perception in the reader.

8. Novcls such as Agustin YMiez's AI filo del ag/'/{1 (1947) and Leopoldo Marecha],s Addn

Buel/osa)'res (1948) bring an encyclopedic approach to the exploration of national identity and

origins to Mexico and Argentina respectively. Doris Sommer discerns a si milar trend when she

asserts that the novels of the Boom rewrite the Spanish American fictions (27-29).

9. Hayden White traces Hegel 's intluence on historical and philosophical discourse.

10. In The Theory f The Novel, he writes that "The novel seeks, by giving fonn, to uncover

and construct the concealed totality of life" (60).

II. Lukacs develops a model for an allegorical relationship between characters in the novel

and real world social problems (54-55).

12. Djelal Kadir details the underlying presence of a Hegelian concept of the Absolute in Terra

NOSTra in his chapter on the novel in QueSTing Fictions; and Gonzalez Echevarria has demon

strated Fuentes' familiarity wit h Lukacs's thought on the origins of the novel (90-91).

13. Gonzalez Echevarria has described the vast array of social , cultural, and historical referents

that appear in Terra NosTra as functioning on a basic metonymical relationship with reality: "Cul

ture and history are a structure of knowledge, a key for the comprehension of everything that pre

cedes the text and gives it meaning" (89). Juan Goytisolo also remarks on the breadth of the cul

tural referents that appear in Terra Nos/ra: "Las libeJ1ades que se toma Fuentes con nuestro

patrimoni o cultural son indice de una ambicion creadora omnivora. Su museo imaginario abarca

por igual novel as y cr6nicas, pinturas, leyendas, ciencias y mitos" (237). Goytisolo concludes that

Anderson SYMPOSIUM 77

Terra Nostra reads like "un saqueo cultural" (250). Marquez Rodriguez is si milarl y attracted by

the scope of cultural motifs found in the novel: "La historia es el trasfondo. Sobre este se entrete

jen la poiftica, las pasiones humanas, la mitologia, las artes, la filosoffa, la religion, La

antropologia, la psicologia, la educacion, la teologfa, el esoterismo, la hechicerfa, la cabala, las

ciencias, la tecnologia, la gastronomia [.. .)" (191-92). As Oviedo sums up, "Lo que esta novel a

quiere ser es, sencillamente, todo: una suma de los mitos humanos, una reescritura de la historia,

una interpretacion de Espana, una reflex ion americana, un ensayo disidente sobre la funcj6n de

la religi6n, el me y la literatura en el destino humano, una propuesta ut6pica, un collage de otras

obras, un tratado de erudici6n, una novela de aventuras, un nuevo di1ilogo de la lengua, un exa

men del pasado, una predkci6n del futuro y (no por ultimo) un inmenso poema er6tico" (19).

14. For a further discussion of the complementarity of Bakhtin's and Lukacs' s views on the

novel, see Hall.

15. In Anxiety of Influence, Bloom studies literary influence as an overbearing accumUlation

of texts and precursors that causes poets psychological anxiet y and a feeling of "belatedness" that

becomes evident in their need to affirm their originality and deny their antecedents.

16. Borges elaborates an alternative theory of influence in "Kafka y sus precursores," in which

authors "create" their predecessors in their own image, thus modifying our reading of past texts.

17. By extension, the Spanish Empire and all other colonial powers are also implicated.

18. See Williams's chapter on Terra Nostra in The Writings of Carlos Fuentes, in which he

develops a series of parallels between the labyrinthic structure ofEI Escorial and that of the novel.

19. "Universal" is employed here with reference to the manner in which it was used by

Fuentes, Vargas Liosa, and other Latin American writers throughout the twentieth century, going

back at least as far as Alfonso Reyes, to denote a largel y Western myth of common cultural ori

gins. Likewise, "Absolute" refers to the Hegelian Absolute cited earlier in this study.

20. A tangled network of narrators shares the task of storytelling, some of whom (s uch as the

Cronista) actually question the truthfulness of their narration. However, as Gonzalez Echevarria

points out, the authorial voice of Fuentes' companion essay to the novel, Cervantes a la cr[tita

de una leclUra ( 1976), spills over into Terra Nost ra, fixing the meaning and the authority of the

text (90-91).

21. Fuentes establishes the complementarity of this text with Terra Nostra by including a

"shared" bibliography for the two works at the end of Cervantes.

22. Susan Suleiman studies how redundancy works to enforce a single reading of a text,

23. Speaking against a superficial reading of Fuentes' deconstruction of historiographic dis

course, Van Delden affirms that "Fuentes does not fictionalize history in order to demonstrate the

distance between text and realit y. Hidden within the fiction of Terra Nostra, there is a reading of

the past that we as readers are meant to take with utter seriousness" (139).

24. In a review that appeared shortly after the publication of the novel, Mexican writer and crit

ic Jose Joaquin Blanco, perhaps sensing this contradiction, accused Fuentes of monologism and

described Terra Nostra as "Iiteratura sin democracia" (14).

WORKS CITED

Alonso, Carlos. The Burdell of Moderniry: The Rhetoric of Cultural Discourse in Latin America.

New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael

Holquist. Austin: U of Texas P, 1981.

Barthes, Roland. "To Write: An Intransitive Verb?" Modern LiTerary Theory: A Reader. Ed. Philip

Rice and Patricia Waugh. London: Arnold, 1998.41-50.

Benda, Julien. La France byzantine 0/./ Ie triomphe de la litlli rature pure: Mallarnui. Gide, Vatery,

Alain. Giraudoux. Suanis. Les S/./mialistes: Essai d'une psychologie originelle du lil/erateur.

Paris: Gallimard, 1945.

Blanco, Jose Joaquin. "Mas alia de la lectura: Las intenciones monumentales." La cultwa en

Mexico 14Jan 1976: 9-16.

Bloom, Harold. The Anxiery of Influence: A TheolY of Poetry. New York: Oxford UP, 1973.

Borges, Jorge Luis. " Kafka y sus precursores." Ficcionario: Una antologla de sus rextos. Ed.

Emir Rodriguez Monegal. Mexico: Tierra Finne, 1998. 307-D9.

78 SYMPOSIUM Summer 2003

Brashear de Gonzalez. Anne. "La Novela Totalizadora: Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow and

Fuentes's Terra Noslro." Kanina 5.2 (198 1): 99-106.

Coddou, Marcelo. "Terra Nostra, 0 la critica de los cielos: Entrevista a Carlos Fuentes." The

American Hispanisl 3.24 (1978): 8-10.

Corra\. Wilfrido. "Novelistas sin tim6n: Exceso y subjetividad en el concepto de la ' novela totaL'"

MLN 116.2 (2001): 315-49.

Ekman, Paul, and Wallace Y. Friesen. "The Repertoire of Nonverbal Behavior: Categories, Ori

gins, Usage, and Coding." Nonverbal Communication, Imeraction, and Gesture: Selections

from Semiotica. Ed. Thomas A. Sebek. The Hague: Mouton, 1981.

Espina. Eduardo. "Terra Noslra: Fragmentos de un discurso miratorio." Ant(podas 8-9

(198R-89): 56-67.

Fiddian. Robin William. "James Joyce and Spanish-American Fiction: A Study of the Origins and

Transmission of Literary Influence." Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 66 (1989): 23-39.

Fuentes. Carlos. La nueva novela ilispanoamericana. Mexico: Moniz, 1969.

---. Terra NosTro. Mexico: Moniz, 1998.

Gonzalez Echevarria, Roberto. "Terra Noslra: Theory and Practice." The Voi ce of the Masters:

WriTing alld AUThority ill Modern Lalill American LiTerature. Austin: U of Texas p, 1988.

Goytisolo. Juan . "Terra NOSlra." Disidencias. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1977.221-56.

Hall. Jonathan. ''Totality and the Dialogic: Two Versions of the Novel?" Tamkang Review I6. 1-4

(1984-85): 5-30.

Hauser, Arnold. The Social HislOry ofArt. Vol. 4. New York: Vintage, 1963.

Hege l, G. W. F. Hegel's Logic: Being Part One of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences.

1830. Trans. William Wallace. Oxford: Clarendon, 1975.

---. 117IroduClion TO the Lectures on the History of Philosophy. Trans. T. M. Knox and A. Y.

Miller. Oxford: Clarendon, 1985.

Huidobro, Vicente. Allrolog(a poe,ica. Ed, Andres Morales, Buenos Aires: Corregidor, 1993.

Iscr. Wolfgang. The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

UP. 1978.

Kadir, Djelal. Qu('slillg PiCliol1s: Latin America's Pamily Romance. Minneapolis: U of Minneso

ta P. 1986.

Kerr. Lucille. "The Paradox of Power and Mystery: Carlos Fuentes's Terra NOSlra," PMLA 95

(1980): 91-102.

Lukacs. Georg. The Theory of the Novel: A HiSlorico-Philosophical Essay on the Porms of Great

Epic Lilerature, Trans, Anna Borstock. Cambridge: MIT P, 1971.

Lyotard, Jean The Posll1wdem Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Trans. Geoff Ben

nington. Minneapolis: U or Minnesota P, 1984.

Marquez Rodriguez. Alexis, "Aproximacion preliminar a Terra Nostra: La ficci6n como reinter

pretacion de la historia." La obra de Carlos Puenles: Una visi6n multiple. Ed. Ana Marfa

Hernandez de L6pez. Madrid: Pliegos, 1'988. 183-92.

Mendelson, Edward. Introduction. Pynchon: A Col/ectioll of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs:

Prentice-Hall, 1978. 1-15.

Oviedo. Jose Miguel. "Fuentes: Sinfonfa del Nuevo Mundo," Hispamerica 6.16 (1977): 19-32.

Poyatos. Fernando. ''The Multichannel Reality of Discourse: Language-Paralanguage-Kinesics

and the Totality of Communicative Systems." Language Sciences 6.2 (1984): 307-37.

Price. David \y, History Made, Hislory imagined: Contemporary Literature, Poesis, and the Past.

Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1999.

Sainz. Gustavo. "Carlos Fuentes: A Permanent Bedazzlement." World Literature Today 57.4

(1983): 568-72.

Sarduy. Severo. "The Baroque and the Neo-Baroque." Latill America ill its Literature. Ed, Cesar

Fernandez Moreno. New York: Holmes. 1980. 115-32.

Sommer, Doris, POUlIdcllional PiCliolls: Th e Natiollal Romances of Latin America. Berkeley: U of

California P, 1991.

Suleiman. Susan. Aulhorilalil'e Pic/ions: The Ideological Novel as a Literary Genre. New York:

Columbia UP, 1983.

Van Delden. Maarten. Carlos Puentes, Mexico, and Modernity, Nashville: Vanderbilt UP,

1998.

Vargas Liosa, Mario. Carta de bawlla por Tircmtlo Blanc. Barcelona: Seix Barral , 1991.

Anderson SYMPOSIUM 79

White, Hayden. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Ninetee11lh-Century Europe. Balti

more: Johns Hopkins UP, 1973.

Williams, Raymond L. The Writings of Carlos Fuentes. Austin: U of Texas P, 1996.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Mark Anderson, Recasting The ChinoDokument13 SeitenMark Anderson, Recasting The Chinomanderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mark Anderson, Treacherous WatersDokument16 SeitenMark Anderson, Treacherous Watersmanderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mark Anderson, Recasting The ChinoDokument13 SeitenMark Anderson, Recasting The Chinomanderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mark Anderson, National Natures and Ecologies of Abjection in Brazilian Literature, 1889-1930Dokument17 SeitenMark Anderson, National Natures and Ecologies of Abjection in Brazilian Literature, 1889-1930manderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mark Anderson, Reappraisal of The Total Novel1Dokument22 SeitenMark Anderson, Reappraisal of The Total Novel1manderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mark Anderson, Yanez's Total Mexico1Dokument22 SeitenMark Anderson, Yanez's Total Mexico1manderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Recasting The Chino PDFDokument13 SeitenRecasting The Chino PDFmanderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Recasting The Chino PDFDokument13 SeitenRecasting The Chino PDFmanderake9999Noch keine Bewertungen