Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Evidence-Based Care of A Patient With A Myocardial Infarction

Hochgeladen von

Lara Denise Tordecilla AbadOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Evidence-Based Care of A Patient With A Myocardial Infarction

Hochgeladen von

Lara Denise Tordecilla AbadCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CLINICAL

Evidence-based care of a patient with a myocardial infarction

Jacinta Kelly

Abstract

Quality nursing care of the patient with a myocardial infarction is realized in accordance with evidence-based practice and by the willingness of nurses to adjust nursing practice as new evidence emerges. The framework for the holistic care of the patient following a myocardial infarction encompasses a comprehensive assessment, planning, intervention and evaluation process. The intention of this case study is to illustrate the rationale and evidence base underpinning the holistic approach to the care of this patient group. However, constant in the care of the patient following a myocardial infarction (MI) is the nursing commitment to an evidence-based holistic approach. Applying a case study method, this article explores the current evidence base that informs the process of assessment, clinical decision making and selection of nursing interventions in the first 12 hours of holistic care of a patient with a MI. A pseudonym is used to maintain the patients anonymity.

CASE PRESENTATION

I

Jacinta Kelly is Postgraduate Nursing Student, Waterford Regional Hospital, Ardkeen, Co. Waterford, Ireland Accepted for publication: December 2003

t is essential to optimize services for patients presenting with cardiac problems to enhance the continuing downturn in death rates from cardiovascular disease (Department of Health and Children, 1999). Consequently, changes in the delivery of health care and the increasing awareness of the need urgently to treat patients with acute coronary syndromes have led to the provision of thrombolysis in the emergency department as opposed to the coronary care unit.

aVR

V1

V4

II

aVL

V2

V5

Joseph Ryan, a 60-year-old man, was admitted to the emergency room of a regional healthcare facility complaining of central chest pain, radiating down his arms and into his jaw. Joseph reported the pain as the worst pain ever; he was short of breath, clammy and nauseous. The pain began approximately 2 hours before admission to the emergency department while he was cutting the hedge and was unrelieved by rest. However, the pain returned and persisted, despite rest. An immediate electrocardiograph (ECG) (Figure 1), together with a brief targeted history and physical examination, confirmed a diagnosis of an inferior MI. An additional right-sided ECG was performed that excluded concurrent right ventricular involvement.

IMMEDIATE NURSING MANAGEMENT IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

III

aVF

V3

V6

V3R

V4R

V5R

V6R

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram indicating Josephs inferior myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation in leads 11, 111, aVF and reciprocal ST segment depression in leads V1V4, 1 and aVL.

In the emergency department, the immediate nursing management was as follows: Joseph and his family were reassured Blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate were ascertained Oxygen therapy was delivered via nasal cannulae at 4 litres per minute Continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation was commenced Continuous cardiac monitoring was applied

12

BRITISH JOURNAL

OF

NURSING, 2004, VOL 13, NO 1

EVIDENCE-BASED CARE OF A PATIENT WITH A MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

Soluble aspirin 300 mg was administered in an effervescent drink Intravenous accesses were placed in the antecubital fossae of both arms Blood specimens were reserved for biochemical profile, full blood count, coagulation studies and troponin I. Observing the indications and contraindications to thrombolysis and in accordance with evidence-based hospital guidelines for the treatment of MI (Table 1), Josephs intravenous thrombolytic and adjunctive therapy were administered with his consent within 20 minutes of arrival at the emergency department. This is referred to as the door-to-needle time, so a time of 20 minutes was duly audited.

PREPARATION FOR TRANSFER

Table 1. Hospital guidelines for the evidence-based treatment of coronary thrombosis

Two puffs of sublingual nitroglycerine were administered at 5-minute intervals to a maximum of 3 x 2 puffs Clopidogrel 300 mg orally Indications and contraindications to thrombolytic therapy were observed Consent to administer thrombolytic therapy was obtained Weight-adjusted dose of intravenous tenecteplase 8000 units (thrombolytic agent) was administered over 10 seconds Subcutaneous low weight molecular heparin at 1 mg/kg Intravenous metoprolol 5 mg over 5 minutes, repeated x 2 to 15 mg total Intravenous Cyclimorph was administered at 2.5 mg that care was taken to maintain his dignity and privacy (Vickers, 2003).

Woodrow (2000) advised that patients with uncomplicated MIs are best cared for in specialist coronary care units. Therefore, attention was directed towards preparing for Josephs safe transfer from the emergency department to the coronary care unit. Specific emphasis was placed on the provision and functionality of vital transfer equipment, such as: Oxygen supply Cardiac monitor Defibrillator Pulse oximetry Emergency drugs. Before Josephs transfer from the emergency room, a precursory history and summary of treatments received was communicated to the coronary care staff by the chest pain nurse specialist. A comprehensive verbal and written report was obtained once Joseph was safely transferred to his monitored coronary care bed.

HOLISTIC ASSESSMENT STRATEGY

Haemodynamic assessment

An assessment of vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate and 12-lead ECG, was immediately undertaken. To assess blood pressure, the left arm was used because of its proximity to the main aorta (Docherty, 2002). The absence of relative coolness of Josephs distal limbs served as a rapid and useful guide to peripheral perfusion (Hillman and Bishop, 1996). ECG monitoring for assessment of dysrhythmias and ST segment elevation was implemented as an assessment tool because it is noninvasive, well tolerated by patients and provides continuous information about the heart (Docherty and Douglas, 2003). However, it should be remembered that the patient is always more important than the monitor (Wark, 1997). ECGs are adjuncts to, and not a substitute for, patient care (Woodrow, 2000). Therefore, it was imperative to observe Joseph as well as the monitor. Furthermore, Darovic and Franklin (1999) advise that assessment of haemodynamic stability should also take into account the pathophysiology and compensatory changes for the patients underlying problem. Subsequently, a working comprehension of the pathophysiology of inferior MI underpinned Josephs haemodynamic assessment process.

In the coronary care unit, a holistic approach to Josephs assessment was carried out which evaluated his total state of being (Dossey et al, 1995). Maintaining accurate clinical records was also essential for an accurate assessment of Josephs physical, psychological and social wellbeing and, whenever necessary, the views and observations of family members were obtained in relation to that assessment (An Bord Altranais, 2002). Throughout his assessment, Joseph was reassured and interventions were explained, which signified

Respiratory assessment

Initial assessment of the patient involved the nurse observing problems, such as visible cyanosis of the lips or being cold to touch (Jevon and Ewens, 2001). Rate, rhythm and

BRITISH JOURNAL

OF

NURSING, 2004, VOL 13, NO 1

13

CLINICAL

regularity of breathing as well as chest expansion were all noted and documented (Docherty, 2002). Chest symmetry, skin condition and accessory muscle use were assessed and documented (Cox and McGrath, 1999). Wilson and Channer (1997) demonstrated that hypoxaemia in the first 24 hours after an MI is a frequent and predictable occurrence that remains undetected unless a pulse oximeter is used. While pulse oximetry was used continuously to assess Josephs oxygenation status, it was acknowledged that there are factors that can interfere with pulse oximeter accuracy (Table 2). However, pulse oximetry is only one component of the complex system of oxygen metabolism (Darovic and Franklin, 1999). Therefore, respiratory assessment was also carried out for signs and symptoms of fatigue, weakness, exertional dyspnoea or dizziness, which may have been indicative of tissue hypoxia (Sole et al, 2001).

Pain assessment

Pain assessment was a priority because continued pain is a symptom of ongoing MI, which places additional risk on non-infarcted myocardial tissue (Urden et al, 2002). Teanby (2003) commented that pain and pain assessment are vital to good medical and nursing care for judging a patients progress, the impact of treatment and occasionally for arriving at a proper diagnosis. The P, Q, R, S, T approach (Table 3) to Josephs chest pain assessment was implemented. To minimize bias and obtain reliable and valid data, the Manchester triage (Figure 2) assessment ruler was also used to assess accurately and consistently the severity of Josephs pain. The Manchester Triage Group (1997) cautioned that the environment and patients perceptions and beliefs can be barriers to effective pain assessment. Therefore, Josephs pain assessment also included noting subjective manifestations such as grimacing, increased muscle tone or restlessness (Kitt et al, 1995).

Table 2. Factors interfering with oximeter accuracy

False-high oxygen saturation levels Hypothermia Ambient light False-low oxygen saturation levels Skin pigment Elevated serum lipids Ambient light Poor signal detection Motion Poor peripheral perfusion Hypothermia

Adapted from Hillman and Bishop (1996)

Anxiety assessment

Josephs level of anxiety was assessed because increased anxiety levels result in raised neuroendocrine activity, which may worsen myocardial ischaemia (Evans, 1998). Verbalization of anxiety, tense facial expression and body movements are indicative of patient anxiety (Sole et al, 2001). Alternatively, autonomic responses to anxiety (rapid pulse rate, increased blood pressure, increased respirations, dilated pupils, dry mouth and peripheral vasoconstriction), are frequently the most reliable index of the degree of anxiety when behavioural and verbal responses are not congruent with the circumstances (Hudak et al, 1998).

OBJECTIVE FINDINGS

Table 3. P, Q, R, S, T approach to chest pain assessment

P Precipitating and palliative factors: patients are asked to describe what brought on the pain and what measures have helped relieve the pain Q Quality: patients are asked to describe in their own words what the pain feels like R Region and radiation: patients are asked to point to the location of the pain and if the pain goes anywhere S Severity: patients are asked to rate the pain on a scale of 110 with 10 being the worst pain ever experienced T Time: patients are asked how long the pain lasts and any temporal associations

Adapted from Urden et al (2002)

Josephs blood pressure was 140/90, oxygen saturation 99% on 4 litres of oxygen/minute, temperature 36.4C and heart rate 92 beats per minute with normal sinus rhythm and resolution of ST segment elevation. Neck vein distension and peripheral oedema were not present. On chest auscultation, there was no evidence of adventitious sounds. Joseph reported his central chest pain as 2 on the Manchester triage scale and described the pain as mild. The results of the biochemistry profile, coagulation studies, full blood count and chest radiograph were unremarkable. However, the specific test

14

BRITISH JOURNAL

OF

NURSING, 2004, VOL 13, NO 1

EVIDENCE-BASED CARE OF A PATIENT WITH A MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

for detection of myocardial damage, troponin I, was decidedly positive at 4.8 ng/dl.

PSYCHOSOCIALSPIRITUAL FINDINGS

Joseph, a widowed farmer with four teenage children, although anxious, was fully alert and oriented on presentation to the coronary care unit (Glasgow Coma Scale 15/15). He lives an active life, smokes 1015 cigarettes daily and consumes alcohol occasionally (around 4 units/week). Joseph enjoyed excellent health until his admission. His hobbies include fishing and supporting Gaelic football. He is a practising Roman Catholic.

NURSING PLAN

glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) 20 mg/20 ml via syringe driver at 0.6 ml/hr was increased to 0.9 ml/hr as per hospital guidelines, to dilate coronary arteries and reduce ischaemic pain (Vickers, 2003). Repeated narcotic drug therapy (morphine sulphate 24 mg intravenous bolus) aimed to relieve pain and anxiety, as this may lead to a lowered threshold for cardiac arrhythmias, increased myocardial workload and provocation of coronary artery

Excruciating Worst ever Very bad Severe

Nursing goals were to relieve Josephs symptoms, limit the extent of myocardial damage, reduce cardiac workload and manage complications (Sole et al, 2001). Josephs nursing care plan incorporated a human perspective (Figure 3), which considered his physical needs in association with his psychological and sociocultural needs (Kinney et al, 1998).

Quite bad Moderate Mild stinging

Interventions for myocardial tissue perfusion

Oxygen therapy was continued at 4 litres per minute via nasal cannulae because it was important to assist the myocardial tissue to continue its pumping activity and to repair the damaged tissue around the site of the infarct (Sole et al, 2001). An upright position was preferable to foster better lung expansion, decreasing venous return, lowering preload and decreasing cardiac workload (Urden et al, 2002). However, if Joseph had been offered a choice of position, it may have helped him retain a sense of control and prevented feelings of powerlessness (Kinney et al, 1998). Oxygen therapy was humidified to prevent damage to ciliary function and to moisten the upper airway, thereby enhancing gas exchange (Adam and Osborne, 1997). Further humidification was offered in the form of mouth care as a comfort measure. Bed rest was also promoted, as it is effective in improving oxygenation, thereby promoting healing and relieving pain (Thompson, 1997).

No pain at all

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

No control

Disabling Stops normal activities

Causes dificulties

Few problems Do most things

Normal activities

Figure 2. Manchester triage pain scale. Adapted from: Manchester Triage Group (1997).

Survival Recovery Minimal suffering

Seen as an individual Provided with information Respected Involved in decision making Receive emotional comfort and support

Physical needs

Family relationships Connection to the real world

Psychological needs

Sociocultural needs

Religious or spiritual beliefs Cultural values

Interpersonal norms

Interventions for pain relief

Having established that Josephs three peripheral vascular lines were patent and intact,

Figure 3. Human needs of the critically ill (adapted from Kinney et al, 1998).

BRITISH JOURNAL

OF

NURSING, 2004, VOL 13, NO 1

15

CLINICAL

Ongoing explanations, reassurance and support were necessary to allay fear and anxiety for Joseph and his family. Indicated by Josephs behavioural, verbal and autonomic responses, the nurses therapeutic use of touch contributed to anxiety reduction and illustrated touch as a powerful tool for preserving patient individuality, coping mechanisms and self-identity...

Table 4. Complications of myocardial infarction

Cardiogenic shock Cardiac rupture Heart failure Sudden death Thromboembolism Ventricular septal defect Ventricular aneurysm Ruptured papillary muscles Extension of myocardial infarction Atrioventricular heart block which frequently follows an inferior wall myocardial infarction with the right coronary artery perfusing the atrioventricular node in 90% of the population

Adapted from Hubbard (2003)

Ensuring that staff conversation did not disturb patients (Kinney et al, 1998) Acknowledging his fears and anxieties (Whiteley et al, 2000) Addressing and treating him respectfully (Kinney et al, 1998) Facilitating his family to be present to touch and comfort their loved one (Whiteley et al, 2000) Active listening (Hudak et al, 1998) Staff identifying themselves by name (Kinney et al, 1998) Consistent use of curtains to maintain his dignity and privacy (Kinney et al, 1998) Pain control (Docherty and Douglas, 2003) Presencing (Kinney et al, 1998) Implementing care in a calm, supportive and confident manner (Sole et al, 2001) Spiritual care (Hudak et al, 1998; Kinney et al, 1998; Sole et al, 2001; Urden et al, 2002) Providing him with a call bell (Urden et al, 2002).

spasm (Thompson, 1997). While morphines vasodilatory properties may have the potential to reduce blood pressure, Woodrow (2000) argues that adequate pain relief is important both for humanitarian reasons and to prevent further stress responses. Further to providing comfort during pain, a relationship of trust, respect and support enabling empowerment of the patient was actively promoted by means of presencing simply being there for the patient and partnership (Taylor, 1992).

Interventions for complications of myocardial infarction

Dysrhythmias are experienced more frequently than any other MI complications, with the incidence at virtually 100% (Hubbard, 2003). Vigilance for ventricular fibrillation with cardiac monitoring was maintained as this represents a life-threatening arrhythmia (Docherty and Roe, 2001). Bed rest was strongly advocated to reduce cardiac workload. To ensure Josephs dignity and comfort and to facilitate monitoring of urinary output, the use of a bedside commode was permitted (Sole et al, 2001). Subsequent to Josephs arrival in the coronary care unit, 510 second runs of an accelerated idioventricular rhythm and frequent premature ventricular contractions were noted. Maj et al (2001) advise that these reperfusion arrhythmias are often self-limiting and may not require treatment. While Joseph did not require intervention, emergency cardiac drugs had nonetheless been made readily available. Nursing interventions also included being alert to any further complications (Table 4). Manifestly, Joseph did not develop complications as significant deviations in his baseline subjective and objective observations were not observed.

Interventions for anxiety and stress relief

Ongoing explanations, reassurance and support were necessary to allay fear and anxiety for Joseph and his family. Indicated by Josephs behavioural, verbal and autonomic responses, the nurses therapeutic use of touch contributed to anxiety reduction and illustrated touch as a powerful tool for preserving patient individuality, coping mechanisms and self-identity (Kinney et al, 1998). However, it was also important to establish and maintain professional boundaries by ensuring that the nurse/patient relationship does not become personal and avoiding over involvement with the patient (Sheets, 2001). Additional measures to prevent Joseph experiencing stress included: Noise control (Urden et al, 2002) Orienting him to the sounds of alarms (Woodrow, 2000)

Interventions for complications of therapy

Bleeding is the most significant potential complication associated with thrombolytic

16

BRITISH JOURNAL

OF

NURSING, 2004, VOL 13, NO 1

EVIDENCE-BASED CARE OF A PATIENT WITH A MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

therapy, particularly intracranial bleeding (Brown et al, 2000). Therefore, ongoing neurological assessment with the Glasgow Coma Scale was implemented as a nursing intervention. Fortunately, Joseph did not exhibit any signs of bleeding, such as neurological changes, hypotension, tachycardia or narrowed pulse pressure (Whiteley et al, 2000). Nonetheless, continuous monitoring of heart rate and rhythm, oxygen saturation and intermittent blood pressure were undertaken. Furthermore, all three vascular access sites were covered with clear, occlusive dressings to facilitate assessment of these sites for bleeding and infection (Casey et al, 1998). Intramuscular injections and further insertion of access devices into non-compressible arterial or venous sites were avoided as thrombolytic therapy disrupts normal blood clotting and could precipitate bleeding via these routes (Maj et al, 2001). Additionally, frequent assessment was carried out for overt bleeding in urine, sputum, gums and stool (Urden et al, 2002). Maj et al (2001) advised that the patient be encouraged to report suspicious signs of bleeding or anaphylaxis, such as headache, lower back pain, nausea, abdominal pain, rash, vomiting, fever or extensive bruising.

CARE OF THE FAMILY

EVALUATION

As a result of timely evidence-based interventions, Josephs vital signs remained stable and resolution of ST segment elevation was sustained. In the first 12 hours of his admission to hospital, Joseph did not display any untoward effects of the thrombolytic therapy or complications of MI, and his chest pain and anxiety resolved completely. Lockhart et al (2000) affirmed that patients who have been admitted to hospital and survive a MI are usually highly motivated to reduce their risk of a further infarction. Therefore, referral forms for the cardiac rehabilitation nurse, dietitian and smoking cessation nurse were prepared. Joseph and his family expressed satisfaction with their overall care.

CONCLUSION

Offering open-ended visiting times as an intervention to reduce the familys crisis response has shown demonstrable benefits (Carr and Clarke, 1997). Hartshorn et al (1997) argued, however, that prolonged visits can deplete the patient of valuable energy required for vital healing and recovery. Therefore, a compromise was found between the familys need for proximity and Josephs need for rest by the nurses ability to reassure the family and provide information without excessive distrubance to Joseph. Research on the needs of families of patients in coronary care units has suggested that the family place utmost importance on having hope and receiving assurances about the treatment and prognosis of the patient (Appleyard et al, 2000). Leske (1998) suggested that the family need to have environmental comforts and supportive interventions available. Table 5 lists practical interventions that were extended to Josephs family.

The rapid expansion in knowledge of the treatment for patients with MI has led to an awareness of the need to adjust practice on an ongoing basis (Brown et al, 2000). In Josephs case, judicious and expeditious initiation of thrombolytic therapy in the emergency department provided an undeniably successful outcome. A safe and well-coordinated transfer of the patient to the appropriate setting of the coronary care unit ensured that further evidence-based assessments and interventions could be provided. A humanistic assessment and intervention strategy encompassing psychological, social, biological and spiritual elements of the person

Table 5. Supportive interventions for Josephs family

Personal needs, such as bathroom facilities, cafeteria and telephone Facilities where they could be alone or privately consult with physicians, counsellors or religious leaders Orientation to coronary care unit Explanation of procedures and treatments Education Supplementary information in pamphlet form Frequent and honest verbal information Involvement in care and decision making Encouragement and support Telephone number of coronary care unit Overnight accommodation in the hospital family room

BRITISH JOURNAL

OF

NURSING, 2004, VOL 13, NO 1

17

CLINICAL

was found to be the most appropriate method by which to care for a patient in the coronary care unit. Interventions were directed at establishing a secure environment, provided by monitoring equipment and experienced coronary care nurses, to observe for complications of MI and of therapy. Consideration for the family was recognized as integral to providing holistic care for the patient in the coronary care unit. Evaluation of the patient identified the need to provide further supportive measures in the form of secondary prevention, rehabilitation and education. This article has demonstrated that the optimal care of the patient presenting with an acute MI relies on the commitment of critical care nurses to the application of current evidence-based holistic practices and their enthusiasm to embrace new roles as new evidence emerges. BJN

Adam SK, Osborne S (1997) Critical Care Nursing: Science and Practice. Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford An Bord Altranais (2002) Recording Clinical Practice Guidelines to Nurses and Midwives. An Bord Altranais, Dublin Appleyard ME, Gavaghan SR, Ananian L, Tyrell R, Carroll DL (2000) Nurse-coached intervention for the families of patients in critical care units. Crit Care Nurse 20(3): 408 Brown A, Horgan J, Conway M et al (2000) Thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction: Third Irish Working Party Consensus. Ir J Med Sci 169: 979 Carr JM, Clarke P (1997) Development of the concept of family vigilance. West J Nurs Res 19: 72639 Casey K, Bedker DL, Roussel-McElmeel PL (1998) Myocardial infarction: review of clinical trials and treatment strategies. Crit Care Nurse 18(2): 3952 Cox LC, McGrath A (1999) Respiratory assessment in critical care units. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 15: 22634

KEY POINTS

A holistic approach to the nursing care of the patient with a myocardial infarction is well supported by evidence and literature. Effective communication and safe transfer of the coronary care patient to a monitored environment is paramount. Application of a holistic assessment, planning, intervention and evaluation strategy is conducive to quality care in this client group. Research-based evidence provides information on how to adjust nursing practice to optimize patient care.

Darovic GO, Franklin CM (1999) Handbook of Haemodynamic Monitoring. WB Saunders, Philadelphia Department of Health and Children (1999) Building Healthier Hearts. Department of Health and Children, Dublin Docherty B (2002) Cardiorespiratory physical assessment for the acutely ill: 2. Br J Nurs 11: 8007 Docherty B, Douglas M (2003) Cardiac care: 1. Interpretation of electrocardiogram rhythm strips. Prof Nurse 18: 3225 Docherty B, Roe J (2001) Cardiac arrhythmias: recognition and care. Prof Nurse 16: 14926 Dossey BM, Keegan L, Guzetta CE, Kolkmeier LG (1995) Holistic Nursing. A Handbook for Practice. 2nd edn. Aspen Publishers, Gaithersburg Evans P (1998) The Psychology of Health: An Introduction. 2nd edn. Routledge, London Hartshorn JC, Sole ML, Lamborn ML (1997) Introduction to Critical Care Nursing. 2nd edn. WB Saunders, London Hillman K, Bishop G (1996) Clinical Intensive Care. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Hubbard J (2003) Complications associated with myocardial infarction. Nurs Times 99(15): 289 Hudak CM, Gallo BM, Morton PG (1998) Critical Care Nursing. A Holistic Approach. 7th edn. Lippincott, Philadelphia Jevon P, Ewens B (2001) Assessment of a breathless patient. Nurs Stand 15(16): 4853 Kinney MR, Dunbar SB, Brooks-Brunn JA, Molter N, Vitello J M (1998) AACN Clinical Reference for Critical Care Nursing. 4th edn. Mosby, London Kitt S, Selfridge-Thomas J, Proehl JA, Kaiser J (1995) Emergency Nursing. A Physiological and Clinical Perspective. 2nd edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia Leske JS (1998) Treatment for family members in crisis after critical injury. AACN Clinical Issues 9(1): 12939 Lockhart L, McMeeken K, Mark J, Cross S, Tait G, Isles C (2000) Secondary prevention after myocardial infarction: reducing the risk of further cardiovascular events. Coronary Health Care 4: 8291 Maj M, De Jong J, Sabadie-Garretson W (2001) Tenecteplase: a promising new fibrinolytic agent. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 20(6): 1923 Manchester Triage Group (1997) Emergency Triage. BMJ Publishing Group, London Sheets VR (2001) Professional boundaries. Staying in the lines. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 20(5): 3640 Sole ML, Lamborn M, Hartshorn J (2001) Introduction to Critical Care Nursing. WB Saunders, Philadelphia Taylor BJ (1992) Relieving pain through the ordinariness in nursing. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 15: 3343 Teanby S (2003) A literature review into pain assessment at triage in accident and emergency departments. Accid Emerg Nurs 11: 1217 Thompson PL (1997) Coronary Care Manual. Churchill Livingstone, New York Urden LD, Stacy KM, Lough ME (2002) Thelans Critical Care Nursing. Diagnosis and Management. Mosby, London Vickers D (2003) Management of a patient admitted with acute non-ST-elevation MI. Prof Nurse 18: 2935 Wark K (1997) Electrocardiography, defibrillation, pacing and pacemakers. In: Goldhill D, Withington S, eds. Textbook of Intensive Care. Chapman & Hall Medical, London Whiteley SM, Bodenham A, Bellamy MC (2000) Churchills Pocketbook of Intensive Care. Churchill Livingstone, London Wilson AT, Channer KS (1997) Hypoxaemia and supplemental oxygen therapy in the first 24 hours after myocardial infarction: the role of pulse oximetry. J R Coll Physicians Lond 31(6): 65760 Woodrow P (2000) Intensive Care Nursing. A Framework for Practice. Routledge, London

18

BRITISH JOURNAL

OF

NURSING, 2004, VOL 13, NO 1

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Bedside Procedures for the IntensivistVon EverandBedside Procedures for the IntensivistHeidi L. FrankelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence-Based Nursing Care of Patient With Acute Myocardial Infarction: Case ReportDokument7 SeitenEvidence-Based Nursing Care of Patient With Acute Myocardial Infarction: Case ReportAhmed AlkhaqaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Improving Patient CareDokument10 SeitenImproving Patient CarebrookswalshNoch keine Bewertungen

- KASUS KELOMPOK 4 A Dan 4 BDokument2 SeitenKASUS KELOMPOK 4 A Dan 4 BAngelika MayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACS Case StudyDokument26 SeitenACS Case StudyMari Lyn100% (1)

- Effectiveness of Chinese Hand Massage On Anxiety Among Patients Awaitng Coronary AngiographyDokument8 SeitenEffectiveness of Chinese Hand Massage On Anxiety Among Patients Awaitng Coronary AngiographyLia AgustinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Safety of Mobilisation and Its Effect On Haemodynamic and Respiratory Status of Intensive Care PatientsDokument11 SeitenThe Safety of Mobilisation and Its Effect On Haemodynamic and Respiratory Status of Intensive Care PatientsRavneet singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- CorrespondenceDokument3 SeitenCorrespondenceFayza RihastaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simulation Acute Coronary Syndrome (Learner)Dokument2 SeitenSimulation Acute Coronary Syndrome (Learner)Wanda Nowell0% (1)

- Incidence Severity and Detection of Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Perturbations in Postoperative Ward Patients After Noncardiac Surgery ScienceDirectDokument6 SeitenIncidence Severity and Detection of Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Perturbations in Postoperative Ward Patients After Noncardiac Surgery ScienceDirectChristian OpinaldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pain Assessment Tool in The Critically Ill Post-Open Heart Surgery Patient PopulationDokument27 SeitenPain Assessment Tool in The Critically Ill Post-Open Heart Surgery Patient PopulationjheighreinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Report: Diabetic Myonecrosis: Uncommon Complications in Common DiseasesDokument3 SeitenCase Report: Diabetic Myonecrosis: Uncommon Complications in Common DiseasesRezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Analysis of Christopher Hammitt CaseDokument8 SeitenNursing Care Analysis of Christopher Hammitt CaseKelly J Wilson0% (1)

- Analgesia en Apendicitis AgudaDokument3 SeitenAnalgesia en Apendicitis Agudasilvia barbosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eco in Cardiac Sugrery Anesthesic 1-s2.0-S1053077020305875-MainDokument11 SeitenEco in Cardiac Sugrery Anesthesic 1-s2.0-S1053077020305875-MainCésar Marriaga ZárateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnostic Values of Chest Pain History, ECG, Troponin and Clinical Gestalt in Patients With Chest Pain and Potential Acute Coronary Syndrome Assessed in The Emergency DepartmentDokument9 SeitenDiagnostic Values of Chest Pain History, ECG, Troponin and Clinical Gestalt in Patients With Chest Pain and Potential Acute Coronary Syndrome Assessed in The Emergency DepartmentMonica Gabriella K. TambajongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whole Body Massage For Reducing Anxiety and Stabilizing Vital Signs of Patients in Cardiac Care UnitDokument10 SeitenWhole Body Massage For Reducing Anxiety and Stabilizing Vital Signs of Patients in Cardiac Care UnitTina AgustinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Article: Review and Outcome of Prolonged Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDokument9 SeitenReview Article: Review and Outcome of Prolonged Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation28121998Noch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Simulation Day 1 Care Plan ms3 Chest Pain SHDokument3 SeitenClinical Simulation Day 1 Care Plan ms3 Chest Pain SHapi-575469761Noch keine Bewertungen

- jcm-08-00051-v2Dokument7 Seitenjcm-08-00051-v2joelruizmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Relaxation Training On Patient-Perceived Measures of Anxiety, Pain, and Outcomes After Interventional Electrophysiology ProceduresDokument7 SeitenImpact of Relaxation Training On Patient-Perceived Measures of Anxiety, Pain, and Outcomes After Interventional Electrophysiology Proceduresdaedalusx99Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nur 111 Session 4 Sas 1Dokument6 SeitenNur 111 Session 4 Sas 1Zzimply Tri Sha UmaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Association Between Emergency Department Crowding and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Chest PainDokument10 SeitenThe Association Between Emergency Department Crowding and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Chest PainGrace Angelica Organo TolitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Original Research: Intensive Care Unit Structure Variation and Implications For Early Mobilization PracticesDokument12 SeitenOriginal Research: Intensive Care Unit Structure Variation and Implications For Early Mobilization Practicesandi kurniawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief CB Intervention in Refractory AnginaDokument7 SeitenA Brief CB Intervention in Refractory Anginagerard sansNoch keine Bewertungen

- BARRIERS TO ICU MOBILIZATIONDokument4 SeitenBARRIERS TO ICU MOBILIZATIONTote Cifuentes AmigoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cabot 2007Dokument10 SeitenCabot 2007Luis Andres Villar InfanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- A. Discussion of The Health ConditionDokument5 SeitenA. Discussion of The Health ConditionPeter AbellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Pain in Intensive Care Units: EpidemiologyDokument9 SeitenManaging Pain in Intensive Care Units: EpidemiologyMega SudibiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qara Syifa Fachrani - 2010221030 - Description of Ventricular Arrhythmia After Taking Herbal Medicines in Middle-Aged CouplesDokument4 SeitenQara Syifa Fachrani - 2010221030 - Description of Ventricular Arrhythmia After Taking Herbal Medicines in Middle-Aged CouplesQara Syifa FNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thailand Anest,+02-Raviwan-FinalDokument8 SeitenThailand Anest,+02-Raviwan-FinalAldaherlen BangunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sharshar 2009 Debil y EstadiaDokument7 SeitenSharshar 2009 Debil y EstadiaStefania Anahi MartelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To AnesthesiologyDokument68 SeitenIntroduction To AnesthesiologyAmanda PadmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review of Chronic Pain After Inguinal HerniorrhaphyDokument7 SeitenA Review of Chronic Pain After Inguinal HerniorrhaphyStefano FizNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Study of Phenylephrine, Ephedrine and Mephentermine For Maintainance of Arterial Pressure During Spinal Anaesthesia in Caesarean SectionDokument6 SeitenA Comparative Study of Phenylephrine, Ephedrine and Mephentermine For Maintainance of Arterial Pressure During Spinal Anaesthesia in Caesarean SectionInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Xiphodynia - A Diagnostic ConundrumDokument6 SeitenXiphodynia - A Diagnostic Conundrumweb3351Noch keine Bewertungen

- KGD 3 PDFDokument8 SeitenKGD 3 PDFRiyan LeonardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Reducing Time To Analgesia in The Emergency Department Using ADokument10 Seiten5 Reducing Time To Analgesia in The Emergency Department Using AMegaHandayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To AnesthesiologyDokument68 SeitenIntroduction To AnesthesiologyKatherine HermantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consideration of Pain Felt by Patients in The ICU: Commentary Open AccessDokument2 SeitenConsideration of Pain Felt by Patients in The ICU: Commentary Open AccessevernotegeniusNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Journal of CardiologyDokument5 SeitenInternational Journal of CardiologyDiah Kris AyuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy VersusDokument7 SeitenExtracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy VersusGiannis SaramantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypertension Arterielle 2016Dokument5 SeitenHypertension Arterielle 2016Nabil YahioucheNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Challenge of Diagnosing Psoas Abscess: Case ReportDokument4 SeitenThe Challenge of Diagnosing Psoas Abscess: Case ReportNataliaMaedyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Australian Journal of PhysiotherapyDokument24 SeitenThe Australian Journal of PhysiotherapyFadhia AdliahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medi 96 E6490Dokument4 SeitenMedi 96 E6490TheEdgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angina PectorisDokument5 SeitenAngina PectorisyunikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthesia-Related Complications in ChildrenDokument14 SeitenAnesthesia-Related Complications in ChildrenAissyiyah Nur An NisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MoxaDokument8 SeitenMoxaPipita BaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Non-Cardiac Chest PainDokument5 SeitenNon-Cardiac Chest PainRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research ArticleDokument8 SeitenResearch ArticlesefhilaputriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rehabilitation ResearchDokument20 SeitenRehabilitation ResearchebookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthesiology - History and Basic Concepts - LecturioDokument19 SeitenAnesthesiology - History and Basic Concepts - Lecturiowe care when you're not awareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 8Dokument4 SeitenArticle 8umair muqriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bispectral Index Monitoring DesfluraneDokument10 SeitenBispectral Index Monitoring DesfluraneVJNoch keine Bewertungen

- CA Glar 2016Dokument7 SeitenCA Glar 2016bdhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amel 8Dokument7 SeitenAmel 8melon segerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vital Signs: Valid Indicators To Assess Pain in Intensive Care Unit Patients? An Observational, Descriptive StudyDokument7 SeitenVital Signs: Valid Indicators To Assess Pain in Intensive Care Unit Patients? An Observational, Descriptive Studybardah wasalamahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emergence Delirium in Adults in The Post-Anaesthesia Care UnitDokument7 SeitenEmergence Delirium in Adults in The Post-Anaesthesia Care Unitpooria shNoch keine Bewertungen

- NLR As Biomarker of DeleriumDokument9 SeitenNLR As Biomarker of DeleriumbrendaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misoprostol For Treatment of Early Pregnancy LossDokument2 SeitenMisoprostol For Treatment of Early Pregnancy LossJuan KipronoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hubungan Antara Abdominal Perfusion Pressure: (App) Dengan Outcome Post OperasiDokument17 SeitenHubungan Antara Abdominal Perfusion Pressure: (App) Dengan Outcome Post OperasidrelvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Triada de CharcotDokument1 SeiteTriada de Charcotdanitza pilcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barrier Free ArchitectureDokument3 SeitenBarrier Free ArchitectureAmarjit SahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Local Data: Roanoke City and Alleghany Health Districts / 12.28.21Dokument2 SeitenLocal Data: Roanoke City and Alleghany Health Districts / 12.28.21Pat ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zirconia Crowns Improve Patient SmileDokument4 SeitenZirconia Crowns Improve Patient SmileWiwin Nuril FalahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of The Urologic Sepsis SyndromeDokument10 SeitenManagement of The Urologic Sepsis SyndromeNur Syamsiah MNoch keine Bewertungen

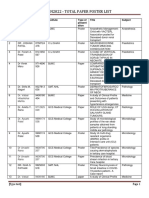

- Amacon2022 - Total Paper Poster List: SR No Presentor Name Contact Number Institute Type of Present Ation Title SubjectDokument35 SeitenAmacon2022 - Total Paper Poster List: SR No Presentor Name Contact Number Institute Type of Present Ation Title SubjectViraj ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smriti Mishra BCG NCCDokument1 SeiteSmriti Mishra BCG NCCashish bondiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- South African Family Practice ManualDokument468 SeitenSouth African Family Practice ManualMahiba Hussain96% (23)

- Pediatric Cardiac Patients: History TakingDokument31 SeitenPediatric Cardiac Patients: History TakingnovylatifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apollo: Reliability Meets Realism For Nursing or Prehospital CareDokument2 SeitenApollo: Reliability Meets Realism For Nursing or Prehospital CareBárbara BabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glossary of EMTDokument5 SeitenGlossary of EMTErnan BaldomeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- BP Monitoring Log BookDokument2 SeitenBP Monitoring Log Bookroland acacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endovenous Microwave Ablation of Great Saphenous VeinDokument3 SeitenEndovenous Microwave Ablation of Great Saphenous VeinMalekseuofi مالك السيوفيNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maritime Declaration of HealthDokument1 SeiteMaritime Declaration of HealthKarym DangerousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abdominoperineal Resection MilesDokument17 SeitenAbdominoperineal Resection MilesHugoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yes, it hurts here.Roxana: I'm going to give you an injection to numb the area. Now I'm going to check the tooth with the probe again. Does it still hurtDokument5 SeitenYes, it hurts here.Roxana: I'm going to give you an injection to numb the area. Now I'm going to check the tooth with the probe again. Does it still hurtCristian IugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Need To Call To Confirm HoursDokument35 SeitenNeed To Call To Confirm HoursRadyusman RajagukgukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ambu BagDokument29 SeitenAmbu BagJessa Borre100% (2)

- ListenDokument105 SeitenListenVinujah SukumaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Autism AlarmDokument2 SeitenAutism AlarmUmair KaziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonopuls 490 User ManualDokument57 SeitenSonopuls 490 User ManualMaryam BushraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individualized Neoantigen-Specific ImmunotherapyDokument16 SeitenIndividualized Neoantigen-Specific ImmunotherapyEhed AymazNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOP 6-Minute-Walk Test 1. General Considerations: 6-Minute Walking Distance: Covered Distance inDokument5 SeitenSOP 6-Minute-Walk Test 1. General Considerations: 6-Minute Walking Distance: Covered Distance inadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- დ მიქელაძის-ბიოქიმიაDokument201 Seitenდ მიქელაძის-ბიოქიმიაJuli JulianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Studies and Research Design PDFDokument5 SeitenTypes of Studies and Research Design PDFPaulina VoicuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leucorrhea KnowledgeDokument3 SeitenLeucorrhea KnowledgeAnamika ChoudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Surgical Hand WashDokument2 SeitenPre-Surgical Hand WashRatna LamaNoch keine Bewertungen