Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Population Health in Transition

Hochgeladen von

Moni SilvyOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Population Health in Transition

Hochgeladen von

Moni SilvyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A

This section looks back to some ground-breaking contributions to public health, reproducing them in their original form and adding a commentary on their significance from a modern-day perspective. John C. Caldwell reviews the 1971 paper by Abdel Omran on the epidemiological transition. Extracts from the original paper are reproduced, by permission, from The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly.

Population health in transition

John C. Caldweir^

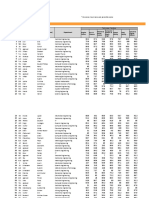

Until recent times most deaths were caused by infectious diseases, degenerative diseases, or violence. Let us ignore violent deaths, as they can occur at any age. Infectious diseases are a threat from the day of birth and, indeed, the very young are most (Susceptible to their attack. People die of degenerative disease^^t older ages because it usually takes time for the body^to degenerate and there is litde else to die from, though they must eventually die of something. What happened in the mortality transition was the conquest of infectious disease, not a mysterious displacement of infection by degeneration as the cause of death. The resulting demographic transition with its changing age of death and the existence of large numbers of people afflicted with chronic degenerative disease (rather than life-threatening infectious disease) is important for planning health services and medical training, which is the current focus of the burden of disease approach. made diseases had replaced infectious ones, which presented a picture of combat between warring camps of disease into which the health professionals could throw themselves. Omran did in places relate this replacemcefTS^ortality decline and changing age structures, though,,he touched upon age structure only ver}' lightlyand usually treated a population as an undifferentiated unit. This approach was central in giving the paper such force. Omran added strength to his argument by segmenting the epidemiological transition into periods with different mortalit}' patterns and disease levels. Thomas iVIcKeown also did this, though only his first two historical papers {3, 4) were published before Omran's. The other form of segmentation Omran used was numbered propositions, to which we now turn. Proposition One, "that mortality is a fundamental factor in population dynamics", has always been agreed: in all demographic transition theories it is the VChy did Abdel Omran's essay (7) have such an prior decline in mortality that in due course impact on the public health community, an impact with precipitates the fertility decline. It is true that for echoes of Malthus's views on population? There are decades after the Second Wodd War demographers certain similarities to The First Essay o^M?i\&{us in 1798: gave more attention to the causes and nature of the Omran firmly stated a number of propositions, which fertility decline than to those ofthe mortality decline, were only sparingly spelled out and buttressed by limited though they stressed that such attention was references. Also, he republished the paper several times necessary because of the preceding unforeseen steep although, unlike Malthus, his additions were largely mortality decline in developing countries. The limited to applying the thesis to the United States and importance of Omran's and IVIcKeown's work is suggesting a fourth stage (2). Omran postulated the that they drew attention to this imbalance. displacement of pandemics by "degenerative and manThe core of Proposition Two, "During the made diseases" without explaining what was meant by transition, a long-term shift occurs in mortality and the latter, but in 1982 he specified that it included disease patterns" is clear, but the subsequent excursion "radiation injur\', mental illness, drug dependency, into the determinants ofthe transition is siibjeet-Kuiie^ traffic accidents, occupational hazards" (2). same criticisms as have been levelled af iMcKeown's-The public health community was undoubtedly work. The ascription of the 19th-century^Western attracted by the prospect of combating man-made mortality decline primarily to ecobiological and diseases: what human activity could create, human socioeconomic factors (McKeown said nutrition), activity could correct. The other attraction was the the argument that "the influence of medical factors suggestion that somehow degenerative and manwas largely inadvertent", and the implication that the struggle against infectipus~disease was unimportant after the turn ofthe century, are all contestable. These ^ Coordinator, Health Transition Centre, National Centre for conclusions were largely drawn from the njortality Epidemiology and Population i-lealth, Australian Nationai University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Austraiia. statistics of Sweden and^_England and Wales. The problem with relegating the 20th centur}' to unimRef. No. 00-0828

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2001, 79 (2) World Health Organization 2001

159

Public Health Classics portance is that it accounts for 66% of the total mortalit)' decline between 1800 and 1971 in England and Wales and 54% in Sweden, much of which can probably be attributed to the reduction in infectious, diseases. There are also difficulties about 19thcentury chronology. In both countries mortality fell quite rapidly between 1800 and 1840, more slowly between 1840 and 1870 (in England hardly at all), and fastest in the last three decades of the centurj'. The improvement between 1800 and 1840 may have been partly propelled by improvements in personal hygiene. Of the ensuing mortality decline from 1840 to the end of the centur)', 86% in England and Wales and 67% in Sweden occurred after 1870. This was the period when advances were made in the treatment of water, the provision of sanitar)' sendees, the removal of waste, and the enforcement of laws against overcrowding. Antiseptics began to be used and, towards the end of the centur\', pasteurization, especially in the form ofthe home boiling of milk for babies. Doctors may have had only limited curative powers but they appear to have given leadership in improving hygiene, midwifery training and child care. On the other hand there is little evidence that nutrition improved (2). Even the limited 18thcentur)' mortality decline can probably be at least partly explained by more effective government action to reduce famine mortality peaks (i), and perhaps also employing findings from the contemporar)' Third World by the growth of the market and transport networks (6). Proposition Three is that "During the epidemioiogic transition the most profound changes in health and disease patterns obtain among children and young women". Certainly mortality rates fell fastest for most ofthe transition among children (7). It is not clear why Omran placed an equal stress on women, though in many countries female mortality falls in the reproductive ages as fertility declines, and men in the West damaged their health to a greater extent than women during the cigarette smoking "epidemic" that began with the First World War. Proposition Four is that "The shifts in health and disease patterns that characterize the epidemioiogic transition are closely associated with the demographic and socioecoriomic transition that constitute the modernization complex". It is plausible to argue that these shifts are the mortality side of the demographic transition. They are all, of course, the result of global economic growth and modernization. But expressing the change as being essentially socioeconomic subdy downgrades the specific contributions made by public health interventions and especially by breakthroughs in medical science. This suspicion receives powerful support from the extraordinary pot-pourri that constitutes Table 4, where everything that has happened to Western society is thrown together as if all of it had causal relationsliips. This table and the accompan)'ing account of consumption output ratios break the lucidity of the developing argument and do litde to enhance it. Proposition Five, with its three basic models of the epidemiological transition, fails to grasp the global nature and the historical sequence of the mortality transition as it spread. In truth, there are probably as many models as there are societies. It underestimates the flow around the world of ideas, behavioural models, education systems, public health approaches and medical technologies. Both Omran and others were tempted to add further stages, pardcularly a stage associated with the reducdon of age-specific death rates of degenerative diseases and the accompanying increase in life expectancy at older ages (2, 8). Omran's essay, together with the work of McKeown, makes the case for a greater concentration on the mortality side of demographic transition. It saw health change as part of social change, and led public health practitioners to regard their activities as of central importance. On the other hand, Omran seemed to argue that the change in the causes of death was a determinant rather than a consequence. His theor)' could be attacked as being insufficiently epidemiological in that its focus was the changing causes of death rather than the changing causes of patterns of illness. It seems so determined to emphasize the role of social change and, to some extent, ecobiological and environmental change, that it goes out of its way to understate the contribudons of scientific inquir)' and medical technology, in spite of their also being products of the modernizadon procesSTFew concessions are made to the roles of laborator)' expfedmentadon in showing how water can beVgudnpd, sewage made safer, and immunization prograniirves rendered possible; of doctors in giving leadership in the 19th centur)'; or of curative medicine at any dme. Its greatest value was to stimulate inquir)'. I

References

1. Omran AR. The epidemioiogic transition; a theory of the epidemiology of population change. Miibank Memoriai Eund Quarteriy 1971.29: 509-538. 2. Omran AR. Epidemioiogic transition. In: RossJA, ed., internationai encydopedia of popuiation. London, The Free Press, 1982: 172-183. 3. McKeown T, Brown RG. Medical evidence related to English population changes in the eighteenth century. Popuiation Studies, 1955,9: 119-141. 4. McKeown T, Record RG. Reasons for the decline in mortality in England and Wales during the nineteenth century. Popuiation Studies, 1962, 16:94-122. 5. Flinn MW. The stabilization of mortality in pre-industrial Western Europe. Journai of European Economic History, 1974, 5f CaldwelpJC. The Saheiian drought and its demographic \ws!ihffons Washington, DC, Overseas Liaison Committee, American Coundl on Education, 1975. 7. Caldwell P. Child survival: physical vulnerability and resilience in adversity in the European past and the contemporary Third World. Sociai Science and Medicine, 1996, 43: 609-619. 8. Olshansky SJ, Ault AB. The fourth stage of the epidemioiogic transition: the age of delayed degenerative diseases. Miibank Memoriai Fund Quarteriy 1986, 64: 355-391.

160

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2001, 79 (2)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hershkovitz I Et Al. 1997. Recognition of Sickle Cell Anemia in Skeletal Remains of Children.Dokument14 SeitenHershkovitz I Et Al. 1997. Recognition of Sickle Cell Anemia in Skeletal Remains of Children.Moni SilvyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dufour DL. 2006. Biocultural Approaches in Human Biology.Dokument9 SeitenDufour DL. 2006. Biocultural Approaches in Human Biology.Moni SilvyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Osteological ParadoxDokument10 SeitenThe Osteological ParadoxMoni SilvyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emerging and Reemerging Infectious DiseasesDokument25 SeitenEmerging and Reemerging Infectious DiseasesNorberto Francisco BaldiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Performance Management System: Business Essentials Business Accelerators Business ValuesDokument10 SeitenPerformance Management System: Business Essentials Business Accelerators Business ValuesVishwa Mohan PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- RealviewDokument62 SeitenRealviewXaxo PapoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A History of The Faculty of Agriculture, University of Port HarcourtDokument56 SeitenA History of The Faculty of Agriculture, University of Port HarcourtFACULTY OF AGRICULTURE UNIVERSITY OF PORT HARCOURTNoch keine Bewertungen

- BC TEAL Keynote Address 20140502Dokument6 SeitenBC TEAL Keynote Address 20140502Siva Sankara Narayanan SubramanianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Synonyms & Antonyms - T Đ NG Nghĩa Trái NghĩaDokument25 SeitenSynonyms & Antonyms - T Đ NG Nghĩa Trái NghĩaDiep NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exalted Signs Sun in AriesDokument6 SeitenExalted Signs Sun in AriesGaurang PandyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pts English Kelas XDokument6 SeitenPts English Kelas XindahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Certification of Anti-Seismic Devices According To The European Standard EN 15129:2009: Tasks For Manufacturers and Notified BodiesDokument9 SeitenCertification of Anti-Seismic Devices According To The European Standard EN 15129:2009: Tasks For Manufacturers and Notified BodiesRobby PermataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maria Bolboaca - Lucrare de LicentaDokument68 SeitenMaria Bolboaca - Lucrare de LicentaBucurei Ion-AlinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vmod Pht3d TutorialDokument32 SeitenVmod Pht3d TutorialluisgeologoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Pose Estimtion SeminarDokument5 SeitenHuman Pose Estimtion Seminarsangamnath teliNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2a Theory PDFDokument41 Seiten2a Theory PDF5ChEA DriveNoch keine Bewertungen

- UgvDokument24 SeitenUgvAbhishek MatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conceptualizing Teacher Professional LearningDokument33 SeitenConceptualizing Teacher Professional LearningPaula Reis Kasmirski100% (1)

- TGC 121 505558shubham AggarwalDokument4 SeitenTGC 121 505558shubham Aggarwalshubham.aggarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labacha CatalogueDokument282 SeitenLabacha CatalogueChaitanya KrishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011bibliography Part I (Preparation and Initial Assessment)Dokument188 Seiten2011bibliography Part I (Preparation and Initial Assessment)Espiritu MineralNoch keine Bewertungen

- Informal and Formal Letter Writing X E Sem II 2018 - 2019Dokument15 SeitenInformal and Formal Letter Writing X E Sem II 2018 - 2019Oana Nedelcu0% (1)

- Membrane TypesDokument92 SeitenMembrane TypesVanditaa Kothari100% (1)

- Barthes EiffelTower PDFDokument21 SeitenBarthes EiffelTower PDFegr1971Noch keine Bewertungen

- Innoventure List of Short Listed CandidatesDokument69 SeitenInnoventure List of Short Listed CandidatesgovindmalhotraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qualifications: Stephanie WarringtonDokument3 SeitenQualifications: Stephanie Warringtonapi-268210901Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stone ChapaisDokument6 SeitenStone ChapaisMaría GallardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transcript Biu2032Dokument5 SeitenTranscript Biu2032Kuna KunavathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Dynamic Model For Automotive Engine Control AnalysisDokument7 SeitenA Dynamic Model For Automotive Engine Control Analysisekitani6817Noch keine Bewertungen

- Skripsi Tanpa Bab Pembahasan PDFDokument67 SeitenSkripsi Tanpa Bab Pembahasan PDFaaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Green ManagementDokument58 SeitenGreen ManagementRavish ChaudhryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Windows Steady State HandbookDokument81 SeitenWindows Steady State HandbookcapellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemistry Chemical EngineeringDokument124 SeitenChemistry Chemical Engineeringjrobs314Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Internasional Tentang ScabiesDokument9 SeitenJurnal Internasional Tentang ScabiesGalyNoch keine Bewertungen