Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Puerto Rico: A Failure of The Modern Colonial Experiment in The Enchanted Isle'

Hochgeladen von

alex_rivera3101Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Puerto Rico: A Failure of The Modern Colonial Experiment in The Enchanted Isle'

Hochgeladen von

alex_rivera3101Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

P20472!

Puerto Rico: A Failure of the Modern Colonial Experiment in the Enchanted Isle

Historical Background1 ! Throughout its modern history, the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico has been

subjected to rule by a foreign power. In 1508, Spanish conquistadores settled on the island, spelling the demise of the native tano people (Arawak amerindians). As a result of disease brought by the Europeans, forced hard labor in gold mines, and an uprising against the Spaniards in 1511, the native population was decimated. By 1520, most of the tanos had disappeared; the small number that remained being decreed free by the Spanish Crown.2 After an unsuccessful attempt at evangelising the natives, the Spanish turned to African slavery as a substitute for the decreasing native workforce. In Tras Monges words, the Spanishs attention turned to saving the souls of the blacks.3 From 1511 until its abolishment in 1873, African slave labor was used, at rst, to sustain the mainly agricultural economy in low prot-yielding crops, such as cassava, cereals, tropical fruits, vegetables and rice; as of the 18th century, slaves worked in the more protable sugarcane, coffee and tobacco plantation system.4 ! Puerto Ricos advantageous geographical position at the entry to the Americas

rst stop en route from the Iberian peninsula on the North Atlantic surface current made it the initial line of defence for the Spanish possessions in the Caribbean and beyond. Other European powers recognised the value of the island, as the French, British and Dutch repeatedly raided the island in hopes of annexing it to their respective

Unless otherwise stated, the historical background is based on Tras Monge, Jos, Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997) Schimmer, Russell, Genocide Studies Program Research Project on Colonial Genocides: Puerto Rico, Yale University, 2010, Web <http://www.yale.edu/gsp/colonial/puerto-rico/index.html>

2 3 4

Trias Monge, op. cit., p. 5 Schimmer, op. cit.

P20472! empires.5 This strategic vantage point would later be recognised, and employed by the United States. ! The Crown exercised direct control of the island via its Council of the Indies,

which regulated and ruled on all matters of law and government. In 1812, the rst Spanish constitution granted the New World colonies full voting representation, Spanish citizenship, male universal suffrage, freedom of expression and assembly, and recognition of human rights. This experiment with representative institutions would be short-lived, as the constitution was overthrown two years later. From then on, Puerto Ricos rights and liberties were caught in a pendulum cycle, as these were continually bestowed and taken away by the Spanish throughout the 19th century. After the Latin American Wars of Independence, Spain began to exercise tighter control over Cuba and Puerto Rico, its last remaining colonies. Puerto Rico experienced increasing tensions among the population, as the island was politically divided among those seeking independence from Spain, those loyal to the Crown who desired full integration, and a third group opting for increased autonomy and self-government without completely seceding from Spain. The advocates of Puerto Rican independence for the island staged a major uprising in 1863, followed by an attempted coup in 1897. The colonial authorities were successful in suppressing these rebellions; however, Spain became increasingly aware of its precarious position vis--vis its remaining colonies. Under pressure from the United States and the colonies independence movements, in 1897, Spain granted the islands their autonomy by decree. The Autonomic Charter of 1897, modelled after the British concept of dominion, represented the attainment of a high level of self-government for the people of Puerto Rico. ! The Autonomic Charter was not to endure, however. In April of 1898, Spain

declared war on the United States, giving rise to the Spanish-American war of 1898. The war culminated in a decisive victory on the part of the United States. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1898) that signalled the end of the war, Spain ceded the

Trias Monge, op. cit., pp.6-8

P20472! islands of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States. Although Cuba

was also to become independent from Spain, the Teller Amendment prevented the U.S. from formally annexing the island. Puerto Rico, on the other hand, was placed under military rule for the following two years until the passage of the Foraker Act of 1900. Rooted on the belief that Puerto Ricans were unt to govern themselves, the Foraker Act established a civilian government headed by American appointees, with limited native-born representation in the legislative branch of government. The passage of this act represented the loss of liberties and rights gained with the Autonomic Charter, mainly Puerto Rico lost the right to government by consent of the governed.6 With the passage of the Jones Act of 1917, United States citizenship was imposed on Puerto Ricans via a process of collective naturalisation. Contrary to its intentions, such imposition heightened the support for independence, and would eventually lead to further deepening of the socio-political cleavages already present, with the status issue being at the forefront of the political discourse, even to this day. ! In the 1940s, the then governor of the island Rexford G. Tugwell, recommended

to President Franklin Roosevelt that Puerto Ricans should be allowed to elect their own governor. The President tasked Congress with creating a commission to evaluate the amendments to the Jones Act that were needed to allow the ofce of Governor to be elected by the Puerto Rican populace. After much deliberation, Puerto Ricans elected their rst governor, Luis Muz Marn, in 1948. The current status of Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico (Commonwealth of Puerto Rico) began as an attempt at regaining self-government for the people of Puerto Rico in the spirit of the Autonomic Charter of 1897. It would have established a constitutional government on the island and dened Puerto Rican citizenship based on a compact of mutual agreement between the United States and Puerto Rico, which could only be altered with the consent of both parties. Despite local efforts, however, Congress decided to uphold United States sovereignty over the island by making the Constitution subject to Congressional approval, and allowing Congress to repeal any law of the

Trias Monge, op. cit., p.43

P20472! Commonwealth of Puerto Rico with which it does not agree. In essence, Congress still

has the power to legislate for Puerto Rico, if it so chooses. With the establishment of the Commonwealth in 1952, the United States was able to deect international attention and criticism of its colonial practices via a facade of self-government, while still maintaining full, unilateral control over Puerto Ricos destiny. ! The rst half of the 20th century, was characterised by the failed project of

American cultural assimilation, a plantation economy based on production and export of sugar, rampant unemployment, poverty and dissatisfaction with the colonial status. During the second half of the century, the developmental policies undertaken aimed to industrialise, develop and improve living conditions on the island. The next section of this paper will therefore examine the poor economic conditions currently experienced on in Puerto Rico in the context of the relative failure of such policies in improving living conditions for a majority of the population. Colonial Economic Development ! Todays Puerto Rico is suffering the consequences short-sighted development

policies, discrimination, and a culture of dependence that has been fostered by the United States since the late 1940s. Operacin Manos a la Obra, or Operation Bootstrap, was a development policy pursued in order to transform the economy of Puerto Rico from the production of primary agricultural products into a modern industrial economy. The approach was to attract foreign direct investment from U.S. enterprises in the form of export-based manufacturing operations that would meet the demands of the United States market. Such a strategy required signicant incentives to lure companies to set-up shop in Puerto Rico. This was mainly achieved by the approval of an exemption from all local taxes coupled with existing federal tax exemptions for enterprises operating on the island. Potentially low wages, political stabilitythe U.S. government being the guarantor of stability via the repression of hardline nationalist or

P20472! other destabilising movements7and a capable workforce rounded out the package offered to companies willing to relocate their production to Puerto Rico.8 ! The potential benets of the industrialisation venture to the Puerto Rican

economy were to come from the increased employment, wages, and improvement in local infrastructure. During the rst two decades of Operation Bootstrap, the program was hailed as a success and a potential model to be followed by other developing nations.9 Income per capita in 1970 had risen to more than ve and a half times that of 1950, trending towards convergence with U.S. per capita income gures.10 The average Puerto Rican experienced an improvement in their livelihood as absolute incomes grew rapidly, allowing families greater purchasing power. Also, the rural, agricultural way of life rapidly shifted into an urban and modern lifestyle for many Puerto Rican families. When analysing several key social indicators from 1950 to 2000, there is evidence supporting an improvement in social conditions on the island. The birth, death, and infant mortality rates dramatically decreased, while life expectancy increased signicantly, from 61 to 74 years.11 ! After 1970, however, the Puerto Rican economy began to lag further and further

behind; the initial gains from previous decades proving to be unsustainable. Although there was reversal of the trend of Puerto Ricos income converging to U.S. levels during the 1970s, that trend resumed during the late 1980s up to 2005, albeit at a very slow pace. By the year 2000, Puerto Ricos income per capita did not even comprise 50 per

For more information on direct U.S. involvement in the repression of the nationalist movement, reference the ofcial FBI documentation titled Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico (NPPR) SJ 100-3, Volume 18 publicly released and published on http://www.pr-secretles.net/binders/SJ-100-3_18_018_152.pdf.

8

Based on Dietz, James L., Puerto Rico: Negotiating Development and Change (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2003), pp.1-22

9

Ibid., p.14 Ibid., p.6 Ibid., pp.7-8

10 11

P20472! cent of the per capita income of Mississippi, the poorest state of the Union.12 Moreover, as Graph 1 13 illustrates, per capita income relative to that of the U.S. started to decline in the past ve years. A similar story emerges when analysing the unemployment rate.

Unemployment, which directly impacts poverty levels on the island, has been sustained at double-digit rates since the 1950s. Graph 2 14 illustrates how the unemployment rate fell from 1950 until 1970, followed by an increase to its highest level around 1980. The unemployment rate fell once more when the development focus was shifted from the industrial sector to the service and high-nance industries during the late 1980s and 1990s. Yet, a new millennium marked a turning point for the worse in Puerto Ricos unemployment rate: from 11 per cent in 2000, it increased gradually up to 16.1 per cent in 2010, inching once more towards the 17 per cent high reached in 1980. Such a pattern in both the unemployment rate and per capita income makes evident that the gains attained when shifting the economic focus are not sustainable in the long-term. ! Another important economic indicator is the labor force participation. This rate

measures the proportion of the labor force (those employed and the unemployed seeking work) to the entire civil population that is of age and able to work. When analysing the data for this indicator, Puerto Rico exhibits dismal results. There has been a signicant downward trend in the labor participation since the 1950s (see Graph 3)14. In 2010, the participation rate reached an all-time low of 42 per cent. This suggests that more than half of the civilian population that is able to work does not participate in the formal labor economy. When coupling labor participation to unemployment, it becomes clear that a signicant portion of the population does not earn wages from legal work. Therefore, real unemployment levels in the island are signicantly worse than the ofcial unemployment rate reects. Under those circumstances, what then explains the sustained increase in personal income in Puerto Rico?

12 13

Ibid., p.6

Data from USDA, Real Historical Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Per Capita and Growth Rates of GDP Per Capita, ERS International Macroeconomic Data Set, 2011, Web <www.ers.usda.gov/data/.../ HistoricalRealPerCapitaIncomeValues.xls>

14

Data from Puerto Rico Planning Board, P.R. Economic Indicators, 2012, Web (http:// www.jp.gobierno.pr/)

P20472! Graph 1

P.R. Per Capita Income as a Percentage of U.S. Income (GDP)

55%

50%

50%

48%

48% 46%

45%

42%

43%

40%

38%

35% 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

Graph 2

P.R. Unemployment Rate 1950-2010

20%

18%

17.0% 16.1%

16%

14.3%

14%

12.9%

13.1%

12%

10.3%

11.0%

10% 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

P20472! Graph 3

P.R. Labor Force Participation Rate 1950-2010

55%

53%

52%

49%

46%

45% 45%

46% 46% 43% 42%

43%

40% 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

As Dietz remarks, poverty decreased because of the growth of federal transfer

payments to individuals that compensated for the structural failures of the development program and industrial phasing to reduce the incidence of poverty.15 Graph 416 highlights the increasing levels of transfer payments that the U.S. government provides qualied individuals in Puerto Rico for nutritional assistance since 1985. In 2010 alone, the U.S. government provided 1.6 billion dollars in assistance, notwithstanding the millions of dollars in Social Security disability payments, and other transfers to the Puerto Rican government. In the year 2000, 44.6 per cent of families in the island had an income that placed them under the U.S. poverty line, that is, inclusive of economic assistance. Thus, transfer payments have not only helped mask the real economic woes that people in Puerto Rico face, but have also contributed to the declining labor

15 16

Dietz, op. cit., p.166

Puerto Rico Planning Board, Economic Report of the Governor, Table 1324. Puerto Rico--Transfer Payments, Web <http://www.gdb-pur.com/economy/documents/2011-05-16-AETabla21-2010.pdf>

P20472! participation rate by incentivising government dependence among the poorest segments of society. In addition, the U.S. minimum wage requirements, which apply to Puerto Rico, has made it increasingly difcult for low-skill workers to nd adequate employment, as there is a surplus of higher-skilled workers ready to accept lower wages, given the meagre availability of prospective jobs.17 Graph 4

Assistance Transfer Payments to Individuals in Puerto Rico

$1,700

1,605

$1,500

Millions of USD

$1,300

1,193 1,063

1,306

$1,100

$900

880

$700

780

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Poverty + Consumerism + Informal Economy => Violence ! The pervasive American cultural values that have been entrenched on the island

have engendered an aspirational standard of living, as many look to the U.S. when devising a rubric for their living conditions. Nevertheless, To live like an American, the average person in Puerto Rico must spend not just tomorrow's wages, but next year's

17

Marxuach, Sergio M., The Puerto Rican Economy: Historical Perspectives and Current Challenges, Luis Muz Marn Foundation Publications, 2007, Web <www.grupocne.org/information_bank/FLMM.pdf>

P20472! wages, today.18 Aided by easily available credit, and the ubiquitous shopping centre,

10

the people of Puerto Rico have adopted rampant consumerist habits, mirroring those of their counterparts in the U.S. mainland.In Puerto Rico, two things are true: Politics is the national sport, and shopping is the national pastime.19 Consumers in the island though are confronted with high unemployment and ination, and relatively low wages, which limit their purchasing power. Given these limitations, how is it then possible to maintain such counterintuitive spending habits? Credit has traditionally been the answer for many; increasingly, however, the informal economy, particularly the drug trade, is providing a relatively fast and effective alternative to obtain the supplemental income needed to maintain, at a minimum, the appearance of a comfortable lifestyle. ! Since the 1980s, Puerto Rico has been ooded with drugs coming from South

American cartels. However, it has not been since the recent U.S.-Mexico crackdown on drug cartels in Mexico, that the Caribbean became prominent in the illicit drug supplychain from South America to the United States. With its unparalleled access to the U.S. mainland, Puerto Rico has become a very important distribution node in the drug network. When set in the context of the recent economic downturn, which greatly affected the island, it is not surprising that when drug trafc increased during this period, plenty of impoverished young men were willing to move it along for an easy buck.20 Again, the diminishing job prospects on the island, lead many not only to depend on the government (which is forced to hand-out less aid per person as the amount of recipients increases), but also to partake in illicit activities such as drug trafcking. This represents another explanatory variable in accounting for the low labor participation rates.

18

Oliver, Lance, Emulating (The Worst Of) The United States, The Puerto Rico Herald, 3 Dec 1999, Web <http://www.puertorico-herald.org/issues/vol3n49/LOEmulatingUS-en.html>

19

Padilla, Maria T., Lovely Island's Pastime: Shop Till You Drop, Orlando Sentinel via The Puerto Rico Herald, 4 Dec 2002, Web <http://www.puertorico-herald.org/issues/2002/vol6n50/LvelyPstmeShopen.html>

20

Sierra-Zorita, Gretchen, Drug Violence at Americas Other Southern Border, The Washington Post, 25 Nov 2011, Web <http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/drug-violence-at-americas-other-southernborder/2011/11/23/gIQAw6uhtN_story.html>

P20472! !

11

Increased economic hardship and the surge in drug trafcking operations on the

island have contributed to the widespread violence that has become a part of the Puerto Rican daily life. Data on the number of murders per year for the island underscore the escalation of violent conict aficting the Commonwealth. Graph 5 21 depicts the number of murders per annum since 1980, revealing a drastic surge in the murder rate, especially in the past 5 years. The year 2011 culminated in an historic record of murders: 1,135 murders in total that year22 , at a rate of 30.6 murders per 100,000 people, one of the highest in the world. The murder rate, however, is only one of the many indicators of violent conict that have consistently increased since the 1990s. ! Although Puerto Rico possesses the second-largest police force in the United

States (around 17,000 police ofcers)23 , their efforts have not been adequate enough to control the situation. Among the problems encumbering the Puerto Rico Police Department are insufcient training, equipment and ofcer pay. Corruption has become the law of the land, as many police ofcers either enable or participate in the drug trade in order to make a quick buck, thereby exacerbating the problem. CNN reported, as a case in point, that In the biggest crackdown on police corruption in the FBI's 102-year history, authorities charged a total of 133 individuals in Puerto Rico [in 2010]...as the result of a probe into whether police provided protection for drug dealers.24 Furthermore, the unbridled corruption across all levels of society and government has fomented an atmosphere of impunity among those involved in the drug trade, helping to incentivise criminal activity over legal work, particularly in the most vulnerable communities.

21

Vico, Manuel L., Compendio de estadsticas: Violencia en Puerto Rico, Tendenciaspr- Project of the University of Puerto Rico, 2009, Web <http://www.tendenciaspr.com>; 2010 Figures from Puerto Rico Police Department, DELITOS TIPO I INFORMADOS EN PUERTO RICO, 2011, Web <www.policia.gobierno.pr/>

22

Rivera Ortiz, Joel, Cifra rcord de asesinatos en el 2011, El Nuevo Da, 1/1/2012, Web <http:// www.elnuevodia.com/cifrarecorddeasesinatosenel2011-1156442.html>

23 24

Sierra-Zorita, op. cit.

CNN Wire Staff, FBI: Puerto Rico cops protected cocaine dealers, CNN Justice, 6 Oct 2010, Web <http://articles.cnn.com/2010-10-06/justice/puerto.rico.arrests_1_puerto-rico-police-department-fbiinformants-drug-trafcking?_s=PM:CRIME>

P20472! Concluding Remarks ! The UN Ofce on Drugs and Crime states that High levels of crime are both a

12

major cause and a result of poverty, insecurity and underdevelopment. Crime drives away business, erodes human capital and destabilises society.25 In Puerto Rico, the present colonial status has been at the heart of the problems currently experienced on the island. The present conditions of poverty and instability have contributed to the surge of violence aficting Puerto Ricans of every walk of life. Such poverty and instability is rooted in misguided policies on the part of the Puerto Rican and American administrations since the colonial experiments inception. ! It can be argued that Puerto Ricans are to blame for their own mistakes since the

granting of the right to elect their own leadership in 1948. Although not entirely untrue, this argument is shortsighted in its perception of Puerto Rican politics. As Dietz points out, The seemingly perpetual search for a solutions to Puerto Ricos status vis--vis the United States...has sapped valuable resources, both human and nancial, that could have been better utilised elsewhere in the economy and in the public sector.26 Moreover, the majority of local elections for both executive and legislative positions are decided on the basis of which political party can garner the most support for its own solution to the status problem, instead of forcing the electorate to choose leaders based on a solid platform that addresses the complex dilemma of stalled economic and social progress27 in Puerto Rico. Notwithstanding the status issue, the islands leaders have also unwisely depended on outside answers for the islands problems, in lieu of Puerto Rican answers to Puerto Rican problems. As Malavet illustrates:

25

United Nations Ofce on Drugs and Crime, UNODC study shows that homicide rates are highest in parts of the Americas and Africa, Global Study on Homicide, 6 Oct 2011, Web <http://www.unodc.org/ unodc/en/frontpage/2011/October/unodc-study-shows-that-homicide-rates-are-highest-in-parts-of-theamericas-and-africa.html>

26 27

Dietz, op. cit., p.177 Ibid., p.14

P20472! Perhaps the greatest damage caused by the United States to the people

13

of Puerto Rico can be labeled their crisis of self-condence. This form of internalised oppression that aficts the people of Puerto Rico has let them to conclude that they are incapable of self-government. That is, Puerto Ricans believe that they lack the economic power to create an independent nation and lack the discipline and intellectual and moral capacity for government.28

Graph 5

Number of Murders Per Annum in Puerto Rico

1200 1050 900

864 894 815 766 695 739 730 983 1135

# of Murders

750 600

572

600

450 472 300 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

28

Malavet, Pedro A., Americas Colony: The Political and Cultural Conict between the United States and Puerto rico (New York: New York University Press, 2004), pp.150-151

P20472!

14

Bibliography

Tras Monge, Jos, Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World (New Haven, CT: Yale ! University Press, 1997) Schimmer, Russell, Genocide Studies Program Research Project on Colonial Genocides: Puerto Rico, ! Yale University, 2010, Web <http://www.yale.edu/gsp/colonial/puerto-rico/index.html> Federal Bureau of Investigation, Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico (NPPR) SJ 100-3, Volume 18, Web ! <http://www.pr-secretles.net/binders/SJ-100-3_18_018_152.pdf> Dietz, James L., Puerto Rico: Negotiating Development and Change (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner ! Publishers, Inc., 2003) USDA, Real Historical Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Per Capita and Growth Rates of GDP Per ! Capita, ERS International Macroeconomic Data Set, 2011, Web ! <www.ers.usda.gov/data/.../HistoricalRealPerCapitaIncomeValues.xls> Puerto Rico Planning Board, P.R. Economic Indicators, 2012, Web (http://www.jp.gobierno.pr/) Puerto Rico Planning Board, Economic Report of the Governor, Table 1324. Puerto Rico--Transfer ! Payments, Web <http://www.gdb-pur.com/economy/documents/2011-05-16-AETabla21-2010.pdf> Marxuach, Sergio M., The Puerto Rican Economy: Historical Perspectives and Current Challenges, Luis ! Muz Marn Foundation Publications, 2007, Web ! <www.grupocne.org/information_bank/FLMM.pdf> Oliver, Lance, Emulating (The Worst Of) The United States, The Puerto Rico Herald, 3 Dec 1999, Web ! <http://www.puertorico-herald.org/issues/vol3n49/LOEmulatingUS-en.html> Padilla, Maria T., Lovely Island's Pastime: Shop Till You Drop, Orlando Sentinel via The Puerto Rico ! Herald, 4 Dec 2002, Web ! <http://www.puertorico-herald.org/issues/2002/vol6n50/LvelyPstmeShop-en.html> Sierra-Zorita, Gretchen, Drug Violence at Americas Other Southern Border, The Washington Post, 25 ! Nov 2011, Web <http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/drug-violence-at-americas-othersouthern-border/2011/11/23/gIQAw6uhtN_story.html> Vico, Manuel L., Compendio de estadsticas: Violencia en Puerto Rico, Tendenciaspr- Project of the ! University of Puerto Rico, 2009, Web <http://www.tendenciaspr.com> Rivera Ortiz, Joel, Cifra rcord de asesinatos en el 2011, El Nuevo Da, 1/1/2012, Web ! <http://www.elnuevodia.com/cifrarecorddeasesinatosenel2011-1156442.html> CNN Wire Staff, FBI: Puerto Rico cops protected cocaine dealers, CNN Justice, 6 Oct 2010, Web <http://articles.cnn.com/2010-10-06/justice/puerto.rico.arrests_1_puerto-rico-police-departmentfbi-informants-drug-trafcking?_s=PM:CRIME> United Nations Ofce on Drugs and Crime, UNODC study shows that homicide rates are highest in parts ! of the Americas and Africa, Global Study on Homicide, 6 Oct 2011, Web ! <http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2011/October/unodc-study-shows-that-homiciderates-are-highest-in-parts-of-the-americas-and-africa.html>

P20472!

15

Malavet, Pedro A., Americas Colony: The Political and Cultural Conict between the United States and ! Puerto rico (New York: New York University Press, 2004) Quintero Rivera, A.G., Conictos de Clase y Poltica (Ro Piedras, PR: Ediciones Huracn, 1977) Duffy Burnett, Christina and Marshall, Burke, Foreign in a Domestic Sense: Puerto rico, American ! Expansion, and the Constitution (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Torts Exam NotesDokument130 SeitenTorts Exam NotesobaahemaegcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories in Criminal LawDokument26 SeitenTheories in Criminal LawSeagal UmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ipc - II MemorialDokument18 SeitenIpc - II MemorialMohd TabishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus-Criminal Law 1Dokument4 SeitenSyllabus-Criminal Law 1Kae EstreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ANDREOPOULOS, 1994. Genocide. Conceptual and Historical DimensionsDokument585 SeitenANDREOPOULOS, 1994. Genocide. Conceptual and Historical DimensionseugeniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Small Project 3 Comparing Local Crime RatesDokument7 SeitenSmall Project 3 Comparing Local Crime Ratesapi-664752911Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection PaperDokument6 SeitenReflection Paperapi-242607057Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1980 BarDokument5 Seiten1980 BarMajho OaggabNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Angry MenDokument3 Seiten12 Angry MenEmmagine E EyanaNoch keine Bewertungen

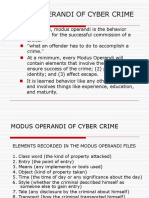

- Modus Operandi of Cyber CrimeDokument10 SeitenModus Operandi of Cyber CrimeRanvidsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Procedure Quiz QuestionaireDokument5 SeitenCriminal Procedure Quiz Questionairejames badinNoch keine Bewertungen

- DigitalForensics Autonomous SyllabusDokument2 SeitenDigitalForensics Autonomous Syllabusswarna_793238588Noch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Ruby in The SmokeDokument2 Seiten7 Ruby in The SmokeAdham DamirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit Jose Carrion Aka BONGDokument19 SeitenAffidavit Jose Carrion Aka BONGMarikitNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNIT - 1 Cyber Jurisprudence & Law, Approaches, Cyber Ethics, Cyber Jurisdictin CompleteDokument41 SeitenUNIT - 1 Cyber Jurisprudence & Law, Approaches, Cyber Ethics, Cyber Jurisdictin CompleteAarzoo Garg0% (1)

- Reading Comprehension Test: Teenage CriminalsDokument5 SeitenReading Comprehension Test: Teenage Criminalsalex92sekulicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fictional DetailsDokument3 SeitenFictional DetailsAllen GomesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Correctional Administration 1: I. Basic Definition of Terms: PENOLOGY DefinedDokument21 SeitenCorrectional Administration 1: I. Basic Definition of Terms: PENOLOGY DefinedTinTinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trifles PresentationDokument30 SeitenTrifles PresentationNgô Thanh Duy0% (1)

- Write A Narrative Essay Beginning With The FollowingDokument2 SeitenWrite A Narrative Essay Beginning With The Followingmiriam harriottNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic Date Case Title GR No Doctrine: People vs. MonjeDokument4 SeitenTopic Date Case Title GR No Doctrine: People vs. MonjeJasenNoch keine Bewertungen

- AML CDD CFT Policy - Customized To UAE Legal Regulatory ObligationsDokument26 SeitenAML CDD CFT Policy - Customized To UAE Legal Regulatory ObligationsMuktinath CapitalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oscar Suarez's Arrest AffidavitDokument10 SeitenOscar Suarez's Arrest AffidavitAmanda RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Venezuela's Gold Heist - Ebus & MartinelliDokument18 SeitenVenezuela's Gold Heist - Ebus & MartinelliBram EbusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rocket Launched PowerPoint TemplateDokument30 SeitenRocket Launched PowerPoint TemplateBảo UyênnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law Pre-WritesDokument1 SeiteCriminal Law Pre-WritesAlex HardenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corad FC BorsbaDokument545 SeitenCorad FC BorsbaAce MapuyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Custodial Torture in BangladeshDokument3 SeitenCustodial Torture in BangladeshpriyankaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 203 - Digest - People V de Guzman - G.R. No. 185843 - 03 March 2010Dokument2 Seiten203 - Digest - People V de Guzman - G.R. No. 185843 - 03 March 2010Christian Kenneth TapiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Think Watson Think - Activity Handouts: © 2019 (24) 7.ai, IncDokument2 SeitenThink Watson Think - Activity Handouts: © 2019 (24) 7.ai, IncValeria AlexandraNoch keine Bewertungen