Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Thakurta Tapati - Monuments, Objects, Histories

Hochgeladen von

Nidhi SubramanyamOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Thakurta Tapati - Monuments, Objects, Histories

Hochgeladen von

Nidhi SubramanyamCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

TAPATI GUHA-THAKURTA.

Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Postcolonial India, Cultures of History 2, New York: Columbia University Press, 2004, xxv, 404 pp. ISBN 0-231-12998-X (Cloth), $ 75.00

It was almost a commonplace to deal with art history of India as consisting of two equally path-breaking periods the first being that of knowledge gathering in British India and the second the nationalist outburst that followed the former. Revealing different values of art and aesthetics over each of these periods was seen as the clearest differentiating aspect of changing models in art historical writings. This consideration pervades an array of proliferating studies on Indian nationalist aesthetics that by now would stand as a nodal point for postcolonial analysis of Indian art history. Tapati Guha-Thakurtas new book, meanwhile, demonstrates that what was common to both periods is the strategies of appropriating the Indias past through art objects. As a result, the survey of the institutions that implemented that appropriation falls under meticulous scrutiny. The main target of the book is related to the practices of the disciplines of archaeology and history and presents a project involving both colonial and native actors which posited a scientific history based on archaeological investigation over textual sources. Colonial politics of the discipline as well as a role that the pioneers in the field of exploration of Indian antiquities, James Fergusson and Alexander Cunningham, played in the creation of the visual and textual archive on the subjects of Indias historical monuments were crucial for valorizing them through attaching

BOOK REVIEWS

237

particular histories to those monuments. It is this concern that is thrown into a sharp focus in Part One of the book dealing with the beginnings of mapping Indias ancient historical sites. Tapati Guha-Thakurtas statement that the project of architectural documentation undertaken by James Fergusson provided the footing for a new scientific discipline is an apparently well-known fact. However the attention paid to the strategies of visualization that no less put the documenting practices of the pioneering scholars in the lineage of picturesque aesthetics of the 18th and 19th centuries is a discerning argument which poses the subject in the framework of aesthetic and intellectual ideas of the period. That is clearly shown in the case of James Fergussons meticulous sketches prepared with his camera lucida on the historical sites, which were targeted to transformation of objects into images by involving aesthetic mediation to pursue the quest for a majestic, better organized and viewable image (p. 112). As Guha-Thakurta rightly argues, the picturesque resonated in his work as a residual aesthetic, mediating the parallel drive for order and history (p. 13). Yet, more than a mere aesthetic compulsion, it was rather the Fergussons method of picking history out of stone that worked through using these pictorial metaphors. From this idea, found in Fergussons early text Picturesque Illustrations, Guha-Thakurta promisingly turns to a larger field of compiling the visual archive of Indian architecture. Here the role of Fergusson was crucial in positing architecture as a far more reliable index of the past in comparison with languages and literatures. However, to pursue the conceptual undertakings in the beginning of the chapter to view Fergussons architectural studies as revolving around a [] method of attaching histories to monuments through the use of analytical formula regarding the development and decline of forms, this point is vaguely delineated and rather boldly stated by the author while dealing with scholars developed methods of historicizing Indian architecture. Even though the divide between Fergusson and Alexander Cunningham as proponents of history of architecture and archaeology can be drawn, from the disciplinary and methodological standpoints both of them provided a foretaste of the kinds of disputes over the veracity of sources and interpretations. Contrary to Fergussons religiously indiscriminating approach to architectural styles of India, Cunninghams attaching histories to the monuments is accomplished with the main focus on ancient Buddhist sites. Encompassed in the predominant Orientalist milieu, Cunninghams preoccupation with Buddhist monuments resulted not so much in drawing a framework for inverted evolution of Buddhist architecture as it was with his contemporary Fergusson, but in demarcating the greatest achievements of imperial India as seen in Sanchi and Amaravati, with Bharhut in between, as representing heydays of Indias Buddhist civilization of the Mauryan and Gupta periods. As Guha-Thakurta puts it, it is the imperial consolidation, once again under the British Empire, that propelled Western fascination with Indias Buddhist past with the primary

238

BOOK REVIEWS

aim to underplay the importance of Brahmanism as the paramount religion of India (p. 37). Thus, the birth of the discipline of field archaeology, the founder figure of which Cunningham is supposed to be, also inaugurated the interpretative strategies that later found their ways both in orientalist and nationalist approaches to the past and present of India. Chapter Two deals with the institution of museum in colonial India, focusing on the ways museums produced and disseminated knowledge, not only supported but also deviated form the idea of the museum as part of the knowledge-producing apparatus. To this end, the chapter addresses the modes of convergence in the twin histories of museums and archaeology in nineteenth-century India, taking the point of variant genealogies of the disciplinesits deviations and dissonancesin the colony rather than adding the particular case to the explorations of Foucauldian theory of technologies of knowledge powers. As a token of these deviations Guha-Thakurta primarily sees the rather new capacity of museums in India, which they gained with the intention of storing up the specimens of living tradition of craftsmanship and at the same time moved from being disciplinary repositories of history and science to being repositories of nations art. The central topic of Chapter Two is the early history of the Indian Museum of Calcutta, which reveals the beginnings of the Indian archaeological collections and the practices of collecting, classification, and display through which museum as a new epistemic institution was produced. Keeping the already mentioned working hypothesis of the early archaeological project as attaching histories to the archaeological monuments and sites, Guha-Thakurta shows progressively how rendering monuments through photographing them, classifying, conserving and providing them with textual accretions in the museum contributed to justifying their historical denomination. However, to avoid a plain statement of these historical denominations being the base for colonial history construction, the author rather aims at revealing the practice of creating history through the display of historical artefacts at the museums. It is persuasively argued that the very practices of accrediting historical meaning by the methods of classification adopted natural history helped to historicize the archaeological relics and produced the historical frame for the art history of India. To put it in other words, it is museum with its modes of historical representation of the artefacts into periods or dynasties that offered, in support of the visual segmentation, a conceptual carcass for the Indian art history as a disciplinary knowledge system which in its own way provided not only Indian history, but also Indias ethnography, religion, mythology, her social and cultural history with historical evidence. Chapter Three sets out to explore the local Indian scholarship that began to guide and inform the colonial project of archaeological investigation and the ways that guidance turned into the sanctioning of national historiography. As a pioneer in the field is considered the art historian Rajendralal Mitra who can be claimed to be the first

BOOK REVIEWS

239

(notwithstanding his predecessor Ram Raz about whom only scarce information is available) native scholar negotiating his identity as an orientalist. Moreover, from the point of view of the projects of writing the history of Indian art, it is he who exercised a turn from Buddhist-centring history to Hindu-centring one. The issues at stake for such turn were rather unconcealed. The dismantling of the antiquity of Buddhist art was supported by claims, apparent from the famous contention with James Fergusson, to expunge the Indias past of any foreign influences, mostly debated in the case of Gandharan Buddhist sculpture. For this reason the Hindu architecture was made the testing grounds of the claims of nations antiquity and uniqueness, since it was never implied, even by his most ardent contestant, that the ancient Aryans [] were dwellers in thatched huts and mud dwellings [] and [first] learnt the art of building from the Grecians (p. 109). While architecture in the form of Orissan antiquities stood, for Rajendralal, as a microcosm of a larger pan-Indian architectural history, sculpture was becoming the tool of physical ethnology, allowing the scholar to pick out from them characteristics of facial features, physiognomy, and costumes that were deemed national (pp.1056). Chapter Four explores the initiatives of the premier Bengali archaeologist, Rakhaldas Banerjee, whose scientific and popular writings in English and Bengali would inscribe the scientific discipline with the regional and national identities. This chapter contributes much to expanding the overall project of nationalist historiography of art, the commencement of which by most scholars, only passingly taking on the subject, used to be associated with its aesthetic discourse in the works of Havel, Coomaraswamy and their peers, thus detaching the early history of writing on Indian art from the field of archaeology. Guha-Thakurta, while touching the key issue of working out the precedence of archaeological over textual sources in historical writings of the period (the more elaborately exposed juxtaposition of those modes of scientific evidences could have shed more light on the propensities of Rakhaldas and his successors history of Indian art as well as its long-established archaeologization), concentrates on the role of Rakhaldas as a nationalist narrator of the historical past of Bengal, employing both scientific material as well as semifictional stories to flesh out the former. The historical novel by Banerjee Pashaner Katha (The Tale of Stone) interestingly presents a chapter in the national historiography that was rather invented by the nationalist imagination of the nineteenth century than scientifically discovered. To quote Guha-Thakurtas accurate remark, the transformation of something fundamentally ambivalent and tenuous into something aggressively self-evident became the mark of success of nationalist ideology (p. 139). However, what needs to be added to the inspecting presentation of nationalist strategies in the writings of Indian art history is that it is the archaeological track hereof that shaped history as devoid of its real actorsarchitects and sculptorsand as acted by the stone monuments after the scenario of epigraphic chronologies.

240

BOOK REVIEWS

Chapter Five deals mainly with the so-called nationalist project in the writings on Indian art. The subject, exhaustively discussed in an earlier book by Guha-Thakurta, The Making of a New Indian Art (Cambridge, 1992), posits the whole nationalist discourse as to offer a discussion on the actors and conditions that made the nationalist discourse a sharp counterstance between historians and aesthetes of Indian art. The positing of the problem and the Bengali sources of the nationalist ideas used are undoubtedly new, at least for English readers, and shed a new evidence on the nationalist agenda in writings on art. The Bengali texts that Guha-Thakurta sets to introduceShyamacharan Srimanis history of Bengal art and Abanindranath Tagores tract on Indian artmark, however, dissenting positions towards the pedigree of Indianness in Indian art that enables to trace the ways whereby orientalist disciplinary knowledge was most effectively transmuted into the language of nationalist art criticism (p. 167). As a consequence of the differentiation of art history and aesthetics as discrete fields that emerges in the nationalist discourse, Guha-Thakurta rightly asserts the idea of the nationalist project being rather an autonomous scholarly endeavour customarily inaccessible to the mainstream art criticism because of its linguistic milieu that pertained to establishing different strategies of transforming Western disciplines into nationalist thought than, as usually thought, an anti-colonial quarrelling against orientalist visions of Indias past that used to monopolize disciplinary science. Chapter Six demonstrates the producing and naturalizing of national identities through mapping Indian art both historically and aesthetically and fixing them institutionally through displaying Indian art at the Exhibition of Indian Art in 1948, New Delhi. This exhibition marks the practice of exhibiting as a national ritual that, in its own, enforces recasting objects from archaeological artefacts to works of art. Made possible through the act of museumizing, this recasting evolves in the turn of Independence as a meaningful strategy of the new secular nation-state formation. Its core designations are fully demonstrated by observing the career of the National Museum at New Delhi as the repository of the nations art treasures whose pedagogical and educational role, yet, would always remain illusory and elusive (p. 204). By problematizing art as a national ritual, mainly in the case of National Museum, New Delhi, Guha-Thakurta pitches predominately the problem of the public in the project of producing the Nations art that is posited against the official agenda. It is this theoretical background that enables to approach the tensions that issued from the positioning of art historical and archaeological knowledges within a mass public domain in contemporary India. To demonstrate the ways of naturalizing histories of the particular artefacts, Chapter Seven discusses the institutional practices that determine the modern biographies of religious art objects coming under the purview of art history. The central image that Guha-Thakurta discusses, the Didarganj Yakshi, is taken here both as an emblem of the

BOOK REVIEWS

241

antiquity of Indian art which became possible by inscribing its Mauryan designations, and as an icon of seductive femininity that, paradoxically, by developing colonial legacy in feminising Indian culture, marked the priority of a new aesthetic gaze. Taking up the arguments of her predecessors in the field of the biographies of art objects, such as Richard Davis, Guha-Thakurta points out how the institutional practices of historicizing the Didarganj Yakshi through display and stylistic investigations led to the investing of Mauryan art history that was by no means seen as a valiant struggle for feeing the history of national art of the burdens of Western (whether Achamaenid and Hellenistic) influences. Evidently the contestations over the identities of the Yakshi thereby pointedly disclose the central tenor of Indian art historiography of the period that was permeated with conflicts over the provenance of style of the early image of Buddha in Gandharan art. Thus, the new designations of yakshis by marking a new framework for the art history also proliferated the new aesthetic values that were by now profoundly related with the symbolism of the nude. Following the lead of the Didarganj Yakshi, the imagery of the archetypical nude as it appears in modern historical art writings, is taken up in Chapter Eight. The topic is of the commodification of the nude that comes into light only due to the penetrating art historical exploration instead of deflecting the overall discourse to the bare political considerations. Although the erotic feminine forms and icons abound in the medieval Indian sculpture, the art historical legitimising the sexualised feminine body, as Guha-Thakurta pointedly argues, required the contentious negotiation of different sets of interpretation. The diversity of these sets is properly illustrated by two cases that exemplify efforts to both to proliferate and obfuscate the theme of sexuality in Indian art: writings on and interpretations of the erotic sculpture of Khajuraho and the condemnations of the depiction of the nude Hindu Godessess by the modern Indian painter Maqbool Fida Husain (so-called Husain affair). By demarcating art historical horizons of treating the nude in Indian art since the 1930s, Guha-Thakurta emphasizes the strategies of valorization of the erotic that range from the concern to differentiate the form and the nature of female nudity in Indian art from their position in the Western tradition to the new obsessive preoccupation with the site of Khajuraho in the 1960s, so-to-call from sole nudity to the celestial beauties (surasundaris). What is common to all these genres of writing about the nudity in art is the continuous reminder of the hidden fund of spiritual and sublime meanings these images encode (pp. 2589). To conclude the topic of institutional identities imposed on the objects of art, the author demonstrates how the archaeological jurisdiction extricating the monuments from the community, under the claim of custody of them, confronts the steadfast religious relationships and capacitates the contestations over them. Finally, Chapter Nine sets up to probe the limits of archaeological jurisdiction that are disclosed when positing archaeological restitution of monuments against sacred

242

BOOK REVIEWS

histories and public remembrance of the sites. Based on the disputes on Ayodhyas Ramjanmabhumi and the Mahabodhi temple in Bodhgaya, the author focuses on the tension which arises between the archaeological valuation of monuments and the spheres of beliefs, imaginings, and residual meanings that lie beyond the bounds of scientific knowledge (p. 278) hereby putting under discussion the very nature of authentic archaeological knowledge. Guha-Thakurta argues that the controversy of contentious identities stems from the tension between the archaeological valuation of monuments and their various alternative configurations, whether in popular, collective memory or () in the nations newly manufactured memory (ibid.). The conclusion drawn is that it is myths and metaphors metamorphosed into true histories that produce historical designations of the sites like those as well as merges the histories of professional historians with those belonging to a larger public. The accurate scrutinizing of the archaeological knowledges, sacred histories, and public remembrance as structures of authority enables the author to trace the rich biographies of two sites with the focal attention to the role of archaeology in the process of producing their true identities. Thus, even though the author leaves the issue open as to the continual redrawing and re-establishing between sacred and secular infringements, between national and extra-national structures of authority (p. 303), the issue proves to emphasize the unambiguous limitations of scientific knowledges and their procedures in dealing with public memories and claimsthe sphere which calls for application of the appropriate theories if one strives to overstep the bonds of a particular knowledge generating discipline whether it were archaeology or art history. Without tracing the disciplinary history of art history and archaeology, Tapati Guha-Thakurta provides the most penetrating and conceptual frame for the institutional history of Indian art the systematic elaboration of which still awaits publication. The research is a valuable chapter in the research onas indicated by the title of the series this book belongs tothe cultures of history of Indian art the knowledge of which will hopefully induce to recoil upon the alternative reconstructions of the cultures of Indian art as replete with gleanings from the theory of art as met in the texts of the shastras or from the data about the real makers of the monuments.

Valdas JASKNAS, Center of Oriental Studies, Vilnius University

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Rootsverb For MSPR 00whit Rich - BWDokument276 SeitenRootsverb For MSPR 00whit Rich - BWgeronpa7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Matilal's Insightful Approach to Understanding Indian PhilosophyDokument11 SeitenMatilal's Insightful Approach to Understanding Indian Philosophypatel_musicmsncomNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cow Is Sucking at The Calf's Teet: Kabir's Upside-Down Language: Linda HessDokument26 SeitenThe Cow Is Sucking at The Calf's Teet: Kabir's Upside-Down Language: Linda HessC Marrewa Karwoski100% (1)

- UtrechtDokument31 SeitenUtrechtAigo Seiga CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Hypnotic SuggestibilityDokument36 SeitenMeasuring Hypnotic SuggestibilityFrancisca GonçalvesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Theory of The Sacrifice in The YajurvedaDokument6 SeitenThe Theory of The Sacrifice in The YajurvedaSiarhej SankoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Note On The Caraka Samhita and BuddhismDokument6 SeitenA Note On The Caraka Samhita and BuddhismJigdrel77Noch keine Bewertungen

- Springer Journal of Indian Philosophy: This Content Downloaded From 5.62.41.138 On Mon, 30 Dec 2019 16:08:58 UTCDokument26 SeitenSpringer Journal of Indian Philosophy: This Content Downloaded From 5.62.41.138 On Mon, 30 Dec 2019 16:08:58 UTCMariana CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddhism in KashmirDokument13 SeitenBuddhism in KashmirDrYounis ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aklujkar Gerow JAOS92.1 SantarasaDokument9 SeitenAklujkar Gerow JAOS92.1 SantarasaBen WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Prison Literatur by Nivin and Lanya PDFDokument18 SeitenEnglish Prison Literatur by Nivin and Lanya PDFJutyar SalihNoch keine Bewertungen

- JIBS - TathagatotpattisambhavanirdesaDokument6 SeitenJIBS - TathagatotpattisambhavanirdesaAadadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smith on Rituals in Religion: Bare FactsDokument9 SeitenSmith on Rituals in Religion: Bare FactsLeleScieriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avatāra - Brill ReferenceDokument8 SeitenAvatāra - Brill ReferenceSofiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- K. Sankarnarayan & Parineeta Deshpande - Ashvaghosha and NirvanaDokument12 SeitenK. Sankarnarayan & Parineeta Deshpande - Ashvaghosha and NirvanasengcanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Initiation Rituals in Shingon and Tibetan Buddhism: Jolanta Gablankowska-KukuczDokument11 SeitenInitiation Rituals in Shingon and Tibetan Buddhism: Jolanta Gablankowska-KukuczAnonymous 8332bjVSYNoch keine Bewertungen

- ASanskrit ReaderDokument448 SeitenASanskrit Readerc_mc20% (1)

- Samarkand, Uzbekistan - Travel GuideDokument1 SeiteSamarkand, Uzbekistan - Travel Guidesh.malika08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thai Buddhism-Some Indigenous Perspectives (1) JDokument10 SeitenThai Buddhism-Some Indigenous Perspectives (1) Jkutty moneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impressive Sculpture of Shiva Battling the Elephant 35Dokument20 SeitenImpressive Sculpture of Shiva Battling the Elephant 35Rahul GabdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rite of Durga in Medieval Bengal An PDFDokument66 SeitenThe Rite of Durga in Medieval Bengal An PDFAnimesh NagarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Galambos 2012 Sir Aurel Stein's Visit To Japan His Diary and NotebookDokument9 SeitenGalambos 2012 Sir Aurel Stein's Visit To Japan His Diary and NotebookRóbert MikusNoch keine Bewertungen

- JIP 06 4 ApohaDokument64 SeitenJIP 06 4 Apohaindology2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Goodding 2011 Historical Context of JīvanmuktivivekaDokument18 SeitenGoodding 2011 Historical Context of JīvanmuktivivekaflyingfakirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Svabhava in CarvakaDokument22 SeitenSvabhava in CarvakaloundoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhāranā From The Perspective of Computer ScienceDokument18 SeitenDhāranā From The Perspective of Computer ScienceJeldsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1969 EandW On The Purification Concept in Indian Tradition With Special Regard To YogaDokument37 Seiten1969 EandW On The Purification Concept in Indian Tradition With Special Regard To Yogawujastyk100% (1)

- Apastamba's Yajna Paribhasha Sutra Index PDFDokument22 SeitenApastamba's Yajna Paribhasha Sutra Index PDFRamaswamy SastryNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rigveda: A Historical AnalysisDokument308 SeitenThe Rigveda: A Historical AnalysisRanjit KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goodwin, Mysticism and Ethics An Examination of Radhakrishnan's Reply To Schweitzer's Critique of Indian ThoughtDokument18 SeitenGoodwin, Mysticism and Ethics An Examination of Radhakrishnan's Reply To Schweitzer's Critique of Indian ThoughtKeren MiceNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sutta On Understanding Death in The Transmission of Boran Meditation From Siam To The Kandyan Court Crosby Skilton Gunasena JIP 2012Dokument22 SeitenThe Sutta On Understanding Death in The Transmission of Boran Meditation From Siam To The Kandyan Court Crosby Skilton Gunasena JIP 2012abccollectiveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vedic Kinship Terms yatar- and giriArDokument5 SeitenVedic Kinship Terms yatar- and giriArSanatan SinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alex Wayman - Two Traditions of India - Truth and SilenceDokument16 SeitenAlex Wayman - Two Traditions of India - Truth and SilenceSzenkovics DezsőNoch keine Bewertungen

- Locative AbsoluteDokument2 SeitenLocative AbsolutesuznsansNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Yantras in Early Saiva TantrasDokument17 SeitenOn Yantras in Early Saiva TantrasJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alikakaravada RatnakarasantiDokument20 SeitenAlikakaravada RatnakarasantiChungwhan SungNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 Verses Critical EditionDokument7 Seiten15 Verses Critical EditionKevin SengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Einoo, Shingo - Ritual Calender - Change in The Conceptions of Time and SpaceDokument0 SeitenEinoo, Shingo - Ritual Calender - Change in The Conceptions of Time and SpaceABNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hiltebeitel - Rethinking The MahabharataDokument187 SeitenHiltebeitel - Rethinking The MahabharatajarubirubiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thompson Richard L. (Aka Sadaputa Dasa) - Vedic Cosmography and Astronomy PDFDokument147 SeitenThompson Richard L. (Aka Sadaputa Dasa) - Vedic Cosmography and Astronomy PDFChandra Bhal SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bronislaw MalinowskiDokument21 SeitenBronislaw Malinowskisoukumar8305Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Sacred Books of The East (Volume 8)Dokument509 SeitenThe Sacred Books of The East (Volume 8)anandrag100% (2)

- Sanskrit and Tamil LiteratureDokument26 SeitenSanskrit and Tamil LiteratureShashank Kumar SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ardhanarishvara PDFDokument10 SeitenArdhanarishvara PDFToniNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Outline of History of KashmirDokument240 SeitenA Outline of History of KashmirVineet Kaul0% (1)

- ShatangayurmantrahDokument3 SeitenShatangayurmantrahExcelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Folk Tradition of Sanskrit Theatre A Study of Kutiyattam in Medieval Kerala PDFDokument11 SeitenFolk Tradition of Sanskrit Theatre A Study of Kutiyattam in Medieval Kerala PDFanjanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kuvalayamala 1Dokument7 SeitenKuvalayamala 1Priyanka MokkapatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06 Chapter 3Dokument101 Seiten06 Chapter 3Cassidy EnglishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mi LindaDokument100 SeitenMi LindatrungdaongoNoch keine Bewertungen

- J. R. Freeman, Possession Rites and The Tantric TempleDokument27 SeitenJ. R. Freeman, Possession Rites and The Tantric Templenandana11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Appaya DikshitaDokument15 SeitenAppaya DikshitaSivasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Archaeological Evidence Identifies Piprahwa as Ancient KapilavastuDokument11 SeitenArchaeological Evidence Identifies Piprahwa as Ancient Kapilavastucrizna1Noch keine Bewertungen

- 3756-Article Text-5897-1-10-20150413Dokument7 Seiten3756-Article Text-5897-1-10-20150413Sanskar MohapatraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Art, Artists, and Its Historical Perspective: International Journal of Academic Research and DevelopmentDokument6 SeitenIndian Art, Artists, and Its Historical Perspective: International Journal of Academic Research and DevelopmentsantonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historiography of Art in Tamil Nadu: Approaches and InterpretationsDokument12 SeitenHistoriography of Art in Tamil Nadu: Approaches and InterpretationsTJPRC PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Art and ArchitectureDokument7 SeitenIndian Art and ArchitectureSonia KhileriNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Primary Sources and Asian Pasts) Primary Sources and Asian Pasts - Beyond The Boundaries of The "Gupta Period"Dokument18 Seiten(Primary Sources and Asian Pasts) Primary Sources and Asian Pasts - Beyond The Boundaries of The "Gupta Period"Eric BourdonneauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and Archetecture AssignmentDokument12 SeitenArt and Archetecture AssignmentAnushree DeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cog TestsDokument31 SeitenCog TestsVictoria DeJacoNoch keine Bewertungen

- AdhdDokument13 SeitenAdhdDilfera HermiatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article Comp Science CJ ST WordDokument32 SeitenArticle Comp Science CJ ST Wordwanda Diaz-MercedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role Play Rubric: Levels of Quality Criteria 4 Excellent 3 Proficient 2 Adequate 1 LimitedDokument8 SeitenRole Play Rubric: Levels of Quality Criteria 4 Excellent 3 Proficient 2 Adequate 1 LimitedAL RYANNE GATCHONoch keine Bewertungen

- Abend-David, D (Ed.) (2014) - Media and Translation: AnDokument4 SeitenAbend-David, D (Ed.) (2014) - Media and Translation: AnedibuduNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADHD and Math Disabilities: Cognitive Similarities and InstructionalDokument7 SeitenADHD and Math Disabilities: Cognitive Similarities and InstructionalNur Dalila GhazaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- IJHRM Violence Resubmission 05-12-16 FinalDokument35 SeitenIJHRM Violence Resubmission 05-12-16 FinalgustaadgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brain Based Teaching and Learning2Dokument14 SeitenBrain Based Teaching and Learning2Gerard-Ivan Apacible NotocseNoch keine Bewertungen

- WTO Public ForumDokument3 SeitenWTO Public ForumNotanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conducting Key Stakeholder InterviewsDokument4 SeitenConducting Key Stakeholder Interviewsfatih jumongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bonus - Take Her Breath AwayDokument42 SeitenBonus - Take Her Breath AwayJohannes Hansen100% (1)

- Musical Form After The Avant-Garde Revolution: A New Approach To Composition TeachingDokument10 SeitenMusical Form After The Avant-Garde Revolution: A New Approach To Composition TeachingEduardo Fabricio Łuciuk Frigatti100% (1)

- City and Sanctuary in Hellenistic Asia Minor Constructing Civic Identity in The Sacred Landscapes of Mylasa and Stratonikeia in KariaDokument10 SeitenCity and Sanctuary in Hellenistic Asia Minor Constructing Civic Identity in The Sacred Landscapes of Mylasa and Stratonikeia in KariaChristina WilliamsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecological Research 2021 Suzuki Animal Linguistics Exploring Referentiality and Compositionality in Bird CallsDokument11 SeitenEcological Research 2021 Suzuki Animal Linguistics Exploring Referentiality and Compositionality in Bird CallsHoney Brylle TandayagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Site Visit NotesDokument2 SeitenSite Visit Notesapi-353818228Noch keine Bewertungen

- RWJF Reality Mining Whitepaper 0309Dokument29 SeitenRWJF Reality Mining Whitepaper 0309rkasturiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Habits and Mistakes Fuel LearningDokument21 SeitenReading Habits and Mistakes Fuel LearningPhong NgôNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conscious DisciplineDokument10 SeitenConscious Disciplineapi-41913050867% (3)

- "If Only HP Knew What HP Knows": The Roots of Knowledge Management at Hewlett-PackardDokument7 Seiten"If Only HP Knew What HP Knows": The Roots of Knowledge Management at Hewlett-Packardhamidnazary2002Noch keine Bewertungen

- MalqDokument1 SeiteMalqaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Mind For NumbersDokument269 SeitenA Mind For NumbersAnil Kumar Jha95% (20)

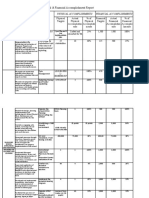

- Physical & Financial Report SummaryDokument26 SeitenPhysical & Financial Report SummaryJanetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploiting Digital ResourcesDokument3 SeitenExploiting Digital ResourcesNiinNoch keine Bewertungen

- English 9: Quarter 3, Module 3Dokument14 SeitenEnglish 9: Quarter 3, Module 3Monaliza PawilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thomas D Albright, Eric R Kandel and Michael I Posner: Cognitive NeuroscienceDokument13 SeitenThomas D Albright, Eric R Kandel and Michael I Posner: Cognitive NeuroscienceCindy Quito MéndezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Feminist Critique of Family StudiesDokument12 SeitenA Feminist Critique of Family StudiesConall CashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 1Dokument4 SeitenLesson 1api-325715593Noch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Perceived Crowding on Mental HealthDokument6 SeitenEffect of Perceived Crowding on Mental Healthshen adindaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 25 PDFDokument6 Seiten25 PDFNirza I. de GonzaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- August 25,2022 NoiseDokument6 SeitenAugust 25,2022 NoiseWenna CellarNoch keine Bewertungen