Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rhino Sinusitis Guidelines

Hochgeladen von

Navin NagarajOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rhino Sinusitis Guidelines

Hochgeladen von

Navin NagarajCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

COMMENTARY Open Access

Canadian guidelines for rhinosinusitis: practical

tools for the busy clinician

Shaun Kilty

Abstract

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) frequently present in clinical practice.

Guidelines for management of these conditions have been published extensively in the past. However, a set of

guidelines that addressed issues specific to the Canadian environment while offering clear guidance for first-line

clinicians was needed, and resulted in the recent publication of Canadian clinical practice guidelines for ABRS and

CRS. In addition to addressing issues specific to Canadian physicians, the presented guidelines are applicable

internationally, and offer single algorithms for the diagnosis and management of ABRS and CRS, as well as expert

opinion in areas that do not have an extensive evidence base. This commentary presents major points from the

guidelines, as well as the intended impact of the guidelines on clinical practice.

See guidelines at: http://www.aacijournal.com/content/7/1/2

Introduction

The first comprehensive Canadian clinical practice guide-

lines for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) and chronic

rhinosinusitis (CRS) have recently been co-published in

Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol [1] and in J Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg [2]. Although rhinosinusitis guidelines

have been issued by European and American medical

societies over the last few years [3-6], and guidance for the

Canadian environment has appeared [7,8], the current

Canadian guidelines mark the first time that comprehen-

sive guidelines covering both ABRS and CRS appear, with

a focus on addressing issues specific to the Canadian

healthcare environment.

The term rhinosinusitis is used to denote inflamma-

tion of the sinus and nasal passages, which often occur

simultaneously due to their close location and shared

respiratory epithelium. Rhinosinusitis is common and

increasing in prevalence worldwide. It is associated with

a significant burden on healthcare services, quality of

patients lives, and lost patient productivity. The preva-

lence of acute rhinosinusitis increased from 11% (or 26

million) of American adults in 2006 [9] to nearly 13%

(over 29 million) in 2009 [10]. Nearly 7 years ago, the

economic burden of the cost of treatment was estimated

at 6 billion dollars annually in the United States [11].

Clearly, as rhinosinusitis continues to affect more indivi-

duals, the impact on patient lives and total costs will

also continue to rise.

Discussion

Because ABRS and CRS have different pathologies and

thus management strategies, it is critical that clinicians

understand these differences so appropriate treatment

can be started. However, analysis of Canadian prescrip-

tion data demonstrated nearly identical prescribing

habits for patients with ABRS and for those with CRS

[12], highlighting that differences in the treatment of

these distinct conditions were not fully appreciated. The

Canadian guidelines provide easy-to-read and practical

recommendations to assist clinicians who face patients

with symptoms of rhinosinusitis in everyday practice.

These guidelines provide specific updates on a variety of

topics, including diagnostic symptom duration and

severity, choice of treatment, appropriate testing, and

antimicrobial resistance issues, in addition to providing

useful diagnostic tools. An overview of the diagnostic

and treatment algorithms is presented in Figure 1.

ABRS diagnosis

The diagnosis of ABRS requires the duration of appro-

priate symptoms be greater than 7 days. Prior guidelines

suggest 5 days with worsening symptoms or 10 days of

persistent symptoms as the lower end of duration [3], or

Correspondence: kiltysj@gmail.com

Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, The Ottawa Hospital,

University of Ottawa, ON, Canada

Kilty BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders 2012, 12:1

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6815/12/1

2012 Kilty; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

symptoms that persist more than 10 days after viral

symptoms present, or worsen within 10 days of initial

improvement [5]. Although symptoms of viral infections

may linger, they reach peak severity by 3 days [13,14].

Thus, the current guidelines recommend that ABRS be

considered for symptoms lasting longer than 7 days

without improvement, or for symptoms that worsens

after 5 to 7 days, or for symptoms that persist after 10

days.

A unique offering of these guidelines is the mnemonic,

PODS, to assist clinicians in recalling the major symp-

toms of ABRS. PODS stands for facial Pain/pressure/

fullness, nasal Obstruction, nasal purulence/postnasal

Discharge, and Smell alterations (hyposmia/anosmia).

For a diagnosis, at least 2 of these major symptoms

must be present, one of which must be O (obstruction)

or D (discharge). To my knowledge, this is the first set

of guidelines offering such a mnemonic for the major

diagnostic criteria of ABRS, which should help clinicians

quickly assess the information that is needed for a diag-

nosis. The guidelines also provide a discussion of pre-

diction rules that describe symptoms whose cumulative

presence increases the likelihood of bacterial infection.

In the absence of diagnostic tests, ABRS diagnosis relies

on clinical symptoms coupled with duration despite

challenges in the accuracy and specificity of signs and

symptoms.

ABRS treatment

Symptom severity plays a role in determining appropri-

ate therapeutic intervention. Previous guidelines have

defined symptom severity either on scores from a visual

analogue score [3] or based upon temperature and pain

severity [5]. The Canadian guidelines base severity by

the degree to which symptoms impair the patient. Thus,

low severity is defined as easily tolerated symptoms,

moderate severity reflects steady symptoms that are tol-

erable, and severe severity indicates that symptoms are

difficult to tolerate or interfere with sleep or daily activ-

ities. This approach does not depend on the presence of

fever, which is not included as a major symptom of

ABRS. Symptom severity is then used to determine ther-

apeutic intervention. For symptoms that are mild to

moderate in intensity, the guidelines recommend the

M

S

A8kS CkS

C C

D D

S S

C C

C C

D D

S S

S

D

WK^

C1

u C8Sn C8Sn

d

C8Sn C8Sn

lnCS

S

A

C

M M S

lnCS

l

M M S

lnCS

A

A 1MSMx

CuS C u

lnCS

A

l

S C8S

Figure 1 Overview of algorithms for ABRS and CRS.

Kilty BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders 2012, 12:1

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6815/12/1

Page 2 of 5

use of intranasal corticosteroids (INCS)but not antibio-

ticsas a first step in treatment. In mild to moderate

severity illness, antibiotics are reserved for patients who

fail to respond to INCS after 3 days and whose symp-

toms continue for more than 7 days. For patients pre-

senting with severe illness, INCS and antibiotics are

recommended in combination as a first step in treat-

ment. This approach thus reserves antibiotics for clear

cases of ABRS that are not resolving spontaneously.

In general, amoxicillin remains the first-line choice for

ABRS, with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX)

or macrolides recommended for individuals with b-lactam

allergy. However, antibiotic choice depends upon other

considerations as well, including local antimicrobial resis-

tance patterns, patient risk of resistance, and risk of com-

plications of failure due to underlying disease. For patients

with risk of resistance or complications of first-line failure,

a second-line agent (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid combina-

tions, fluoroquinolones) is recommended.

CRS diagnosis

A useful mnemonic for quick recall of major symptoms

of CRS is CPODS, standing for facial Congestion/fullness,

facial Pain/pressure, nasal Obstruction/blockage, nasal

Drainage, and Smell dysfunction (hyposmia/anosmia). At

least two of the CPODS symptoms must be present for 8

to 12 weeks, along with documented inflammation of the

nasal mucosa or paranasal sinuses. The duration of

symptoms for diagnosis has generally been proposed as

12 weeks [3,5]. However, Canadian guidelines align with

others in recommending an 8 week minimum for CRS

diagnosis [15]. The guidelines also highlight the insis-

tence of clinical or radiologic evidence in addition to

clinical symptoms in order to make a diagnosis of CRS.

Hence, a diagnosis requires the presence of 2 or more

CPODS, present for 8 to 12 weeks, plus objective evi-

dence using either endoscopy or computed tomography.

A recent study of EP3OS symptom criteria confirmed by

endoscopy reported moderate reliability of symptom-

based diagnosis for CRS, and found stability between

geographic regions [16]. These findings concur with an

earlier study that found that endoscopy was critical to

increase the specificity, and positive and negative predic-

tive values for symptom-based diagnosis of CRS [17].

Although symptom-based diagnosis had poor specificity

by itself, diagnostic accuracy improved dramatically when

combined with an objective finding (odds ratio for CRS

improved from 1.1 to 4.6 [95% CI, 2.3-9.2]).

The presence or absence of nasal polyps is used to

further categorize disease. The presence of bilateral

polyps in the middle meatus characterizes CRS with

nasal polyps (CRSwNP), while the lack of polyps consti-

tutes CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP). The guide-

lines provide detailed description of the physical

examination, including adequate tools for visual rhino-

scopy assessments and description of clinical signs,

which should provide clinicians with a better under-

standing of useful signs and symptoms.

CRS treatment

Because CRS is primarily an inflammatory disease with

unknown contributions from bacteria, cytokines, leuko-

cytes, and tissue remodeling, treatment is based upon

use of INCS as monotherapy or as adjunct therapy with

antibiotics. Before initiating one of these treatments,

predisposing and contributing conditions should be

identified and treated. Conditions that are thought to

contribute to CRS include allergic rhinitis, asthma, cili-

ary dysfunction, immune dysfunction, lost ostia patency,

aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease, and cystic

fibrosis.

Nasal or oral corticosteroids are used with or without

antibiotics for initial treatment of CRSsNP. When pre-

scribed, antibiotics should be a second-line agent with

broad-spectrum coverage (ie, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid

inhibitors, fluoroquinolones) and duration of therapy

should be longer than for ABRS.

For CRSwNP, a course of topical INCS and short

courses of oral steroids are used. Antibiotics are not

recommended for CRSwNP unless there are symptoms

suggesting infection.

Role of antibiotics

These guidelines discuss concerns of increasing rates of

antibiotic resistance, with the emergence of penicillin,

macrolide, and multi-drug resistant S. pneumoniae. Ele-

vated rates of b-lactamase-producing H. influenzae and

M. catarrhalis have also been reported, with conse-

quences for antibiotic choice. Although antibiotic resis-

tance rates increased between 1988 and 2005, some rates

have stabilized in the 5-year period between 2000 and

2005, including rates for ciprofloxacin, penicillin, and

TMP/SMX resistance [18,19]. However, resistance rates

continue to increase for erythromycin and tetracycline,

and penicillin nonsusceptibility remains elevated. Resis-

tance and nonsusceptibility rates also showed regional

differences. Similar patterns of variable and growing anti-

biotic resistance are of global concern, with the World

Health Organization dedicating World Health Day 2011

to the topic of antimicrobial resistance. Because of the

trends in resistance rates, guidelines advise judicious use

of antibiotic therapy and awareness of related issues, with

appropriate selection of therapy for clinical situation.

Ancillary therapy, testing, and prevention

Saline irrigation has emerged in these guidelines as a

strong recommendation from the experts despite limited

evidence. This expert endorsement is in line with the

Kilty BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders 2012, 12:1

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6815/12/1

Page 3 of 5

increased recognition of the benefits of saline therapy

over the last 5 to10 years in the management of sinona-

sal disease. Multiple studies report the benefit of saline

irrigation in patients with CRS [20-22], ARS [23], and in

allergic, acute and chronic rhinosinusitis [24]. The use

of saline irrigation as adjunct therapy is primarily based

upon reported symptomatic improvement and its good

safety profile.

The expert panel endorsed allergy testing in cases of

recurrent episodes of ABRS or for CRS as a potential

contributing condition to these diseases. Indeed, studies

have reported that over half of patients with recurrent

ARS or with CRS tested positive for allergies [25,26].

Whether allergy treatment helps minimize symptoms in

these cases is not known, but knowledge and avoidance

of identified allergens remains a prudent approach none

the less.

Prevention of illness is a recommendation. The impor-

tance of hand washing is highlighted as fundamental to

reduce viral transmission and prevent the development

of ABRS and acute exacerbations of CRS. Although stu-

dies are lacking, the expert recommendation strongly

encourages educating patients regarding strategies to

reduce the likelihood of contracting a viral illness.

Guideline rationale and method

The Canadian clinical practice guidelines for acute and

chronic rhinosinusitis were designed foremost to be a

valuable tool for first-line clinicians, particularly primary

care providers. As such, the guidelines are evidence

based, make specific recommendations, and comprehen-

sively address both ABRS and CRS in single algorithms

for each, while also providing the practitioner with the

opinion of clinical experts.

Previous Canadian guidelines were either outdated or

did not provide guidance for practitioners in best prac-

tices management of patients with ABRS or CRS. The

current guidelines present strategies relevant for Cana-

dian practitioners to negotiate the unique aspects of

their healthcare system, while remaining sufficiently

general to benefit an international audience. Thus, in

situations that might arise in the Canadian healthcare

system, such as delays in obtaining a computed tomo-

graphy scan or specialist referral, action points during

this waiting period are presented. However, the state-

ments and discussions throughout the document focus

on aspects central to ABRS and CRS, and apply in any

healthcare environment. Advances in the pathobiology

of these disease entities are discussed, along with the

current status of treatment options.

The guidelines were constructed using an evidence-

based strategy and present an evidence strength rating,

plus a second rating that reflects the endorsement level

of the multidisciplinary group of experts who represent

medical fields involved in treating this multifaceted con-

dition. This latter rating is particularly useful in areas

where rigorous trials are lacking in quality or number.

The guidelines were further reviewed and endorsed by

the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious

Disease Canada, Canadian Society of Allergy and Clini-

cal Immunology, Canadian Society of Otolaryngology-

Head and Neck Surgery (CSO-HNS), Canadian Associa-

tion of Emergency Physicians, and the Family Physicians

Airways Group of Canada.

The Canadian guidelines provide clear definitions and

discussion of ABRS and CRS. The diagnostic and treat-

ment flow diagrams are complete, providing detail and

ease of flow within a single algorithm for ABRS and for

CRS. The guidelines were designed to improve the

usability for general practitioners and family medicine

physicians. In addition, these guidelines provide current,

clear information for the optimal management of CRS-a

disease entity for which advances in understanding its

pathobiology and effective management strategies con-

tinue to evolve. The steps involved in the diagnosis,

management, and referral of ABRS and CRS, coupled

with strength of recommendation ratings, should help

arm general practitioners with the information necessary

to improve the management of their patients with symp-

toms of rhinosinusitis.

Conclusion

The knowledge base of ABRS and CRS pathology and

management continues to grow and evolve as the role

of pathogens are discerned, antimicrobial resistance

rates change, and treatment strategies are improved.

The Canadian guidelines recognize this changing envir-

onment and provide a solid foundation for future devel-

opments. The guidelines are a much-needed user-

friendly tool for busy physicians who want to quickly

grasp the appropriate methods of diagnosis and manage-

ment of ABRS and CRS. The inclusion of mnemonic

devices to aid in diagnosis, succinct algorithms for each

disease entity, and expert opinion to aid where studies

are lacking create a new level of utility for rhinosinusitis

guidelines. Physicians who desire to understand the cur-

rent state of the pathologies and treatment approaches

for ABRS and CRS will benefit from these guidelines,

and as an extension, their patients will benefit as well.

List of abbreviations

ABRS: acute bacterial rhinosinusitis; CRS: chronic rhinosinusitis; INCS:

intranasal corticosteroids; TMP/SMX: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Acknowledgements and funding

The author thanks Lynne Isbell, PhD for editorial assistance, which was

funded by CSO-HNS.

Kilty BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders 2012, 12:1

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6815/12/1

Page 4 of 5

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Received: 25 March 2011 Accepted: 1 February 2012

Published: 1 February 2012

References

1. Desrosiers M, Evans GA, Keith PK, Wright ED, Kaplan A, Bouchard J,

Ciavarella A, Doyle PW, Javer AR, Leith ES, et al: Canadian clinical practice

guidelines for acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy Asthma Clin

Immunol 7:2.

2. Desrosiers M, Evans GA, Keith PK, Wright ED, Kaplan A, Bouchard J,

Ciavarella A, Doyle PW, Javer AR, Leith ES, et al: Canadian clinical practice

guidelines for acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg 2011, 40(Suppl 2):S99-193.

3. Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J: European position paper on rhinosinusitis

and nasal polyps 2007. Rhinol Suppl 2007, 1-136.

4. Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R, Jones NS, Leech SC, Farooque S,

Ryan D, Walker SM, Clark AT, Dixon TA, et al: BSACI guidelines for the

management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2008,

38:19-42.

5. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S,

Ganiats TG, Gelzer A, Hamilos D, Haydon RC, Hudgins PA, et al: Clinical

practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007, 137:

S1-31.

6. Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R, Jones NS, Drake-Lee AB, Ryan D,

Dixon TA, Huber PA, Nasser SM: BSACI guidelines for the management of

rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis. Clin Exp Allergy 2008, 38:260-275.

7. Desrosiers M, Frenkiel S, Hamid QA, Low D, Small P, Carr S, Hawke M,

Kirkpatrick D, Lavigne F, Mandell L, et al: Acute bacterial sinusitis in adults:

management in the primary care setting. J Otolaryngol 2002, 31(Suppl

2):2S2-14.

8. Diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis: adults. 2008

Update. [http://www.topalbertadoctors.org/cpgs.php?sid=15&cpg_cats=56].

9. Pleis J, Lucas J: Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health

Interview Survey, 2007. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health

Stat 2009, 10.

10. Pleis JR, Ward BW, Lucas JW: Summary health statistics for U.S. adults:

National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Hyattsville, MD: National Center

for Health Statistics; 2010, Series 10, No. 249.

11. Anand VK: Epidemiology and economic impact of rhinosinusitis. Ann Otol

Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2004, 193:3-5.

12. IMS Health: Canadian Disease and Therapeutic Index (CDTI) database.

2006.

13. Gwaltney JM Jr, Hendley JO, Patrie JT: Symptom severity patterns in

experimental common colds and their usefulness in timing onset of

illness in natural colds. Clin Infect Dis 2003, 36:714-723.

14. Gwaltney JM Jr: Rhinovirus infection of the normal human airway. Am J

Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 152:S36-39.

15. Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL, Kaliner MA, Kennedy DW, Virant FS,

Wald ER, Khan DA, Blessing-Moore J, Lang DM, et al: The diagnosis and

management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2005, 116:S13-47.

16. Tomassen P, Newson RB, Hoffmans R, Lotvall J, Cardell LO,

Gunnbjornsdottir M, Thilsing T, Matricardi P, Kramer U, Makowska JS, et al:

Reliability of EP3OS symptom criteria and nasal endoscopy in the

assessment of chronic rhinosinusitisa GA(2) LEN study. Allergy 2011,

66:556-561.

17. Bhattacharyya N, Lee LN: Evaluating the diagnosis of chronic

rhinosinusitis based on clinical guidelines and endoscopy. Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg 2010, 143:147-151.

18. Green K, McGreer A, Church D, Weiss K, Davidson R, Hoban D, Kibsey P,

Kuhn M, Toye B, Pong-Porter S, et al: Trends in antimicrobial resistance in

Canadian strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, 1988-2003. 43rd Annual

Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 9/14/2003

Chicago; 2003.

19. Green K, Pong-Porter S, Plevneshi A, McGeer A, Low EE, Canadian Bacterial

Surveillance Network: Trends in antimicrobial prescribing and

pneumococcal resistance, Canada, 1993-2005. 46th Annual Interscience

Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 9/27/2006 San

Francisco; 2006.

20. Pynnonen MA, Mukerji SS, Kim HM, Adams ME, Terrell JE: Nasal saline for

chronic sinonasal symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007, 133:1115-1120.

21. Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, Scadding G: Nasal saline irrigations for the

symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007,

CD006394.

22. Ottaviano G, Marioni G, Staffieri C, Giacomelli L, Marchese-Ragona R,

Bertolin A, Staffieri A: Effects of sulfurous, salty, bromic, iodic thermal

water nasal irrigations in nonallergic chronic rhinosinusitis: a

prospective, randomized, double-blind, clinical, and cytological study.

Am J Otolaryngol 2011, 32:235-239.

23. Hauptman G, Ryan MW: The effect of saline solutions on nasal patency

and mucociliary clearance in rhinosinusitis patients. Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg 2007, 137:815-821.

24. Ural A, Oktemer TK, Kizil Y, Ileri F, Uslu S: Impact of isotonic and

hypertonic saline solutions on mucociliary activity in various nasal

pathologies: clinical study. J Laryngol Otol 2009, 123:517-521.

25. Emanuel IA, Shah SB: Chronic rhinosinusitis: allergy and sinus computed

tomography relationships. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000, 123:687-691.

26. Alho OP, Karttunen R, Karttunen TJ: Nasal mucosa in natural colds: effects

of allergic rhinitis and susceptibility to recurrent sinusitis. Clin Exp

Immunol 2004, 137:366-372.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6815/12/1/prepub

doi:10.1186/1472-6815-12-1

Cite this article as: Kilty: Canadian guidelines for rhinosinusitis: practical

tools for the busy clinician. BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders 2012 12:1.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color gure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Kilty BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders 2012, 12:1

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6815/12/1

Page 5 of 5

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Anatomy and Physiology of PlacentaDokument5 SeitenAnatomy and Physiology of PlacentaAdrianne Basa100% (1)

- Guidelines For Prescribing EyeglassesDokument18 SeitenGuidelines For Prescribing Eyeglassesratujelita100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

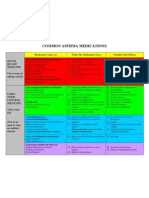

- Common Asthma MedicationsDokument1 SeiteCommon Asthma MedicationsHeart of the Valley, Pediatric CardiologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tall StatureDokument24 SeitenTall StaturedianmutiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Closed Chain Exercises: Dominic S. Adolfo, PTRPDokument56 SeitenClosed Chain Exercises: Dominic S. Adolfo, PTRPEric Carlos YumulNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAMPLE FDAR CHARTING PainDokument1 SeiteSAMPLE FDAR CHARTING Painjpm100% (1)

- Prenatal CareDokument3 SeitenPrenatal CareYolanda Dwi OktaviyaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Therapeutic CommunicationDokument82 SeitenTherapeutic CommunicationYvette Vallejo100% (2)

- HI KPI GuidelinesDokument65 SeitenHI KPI Guidelinesi_kostadinovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- MC-55-157-001 - 1-E Asg-120u Ug PDFDokument56 SeitenMC-55-157-001 - 1-E Asg-120u Ug PDFSiti NurhadijahNoch keine Bewertungen

- FY 1 Antimicrobial PrescriptionDokument10 SeitenFY 1 Antimicrobial Prescriptiongus_lionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- TITLE-class Diagram For Hospital Management SystemDokument2 SeitenTITLE-class Diagram For Hospital Management SystemShivam JhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boy: - 2. Bus: - 3. Box: - 4. Mouse: - 5. Child: - 6. BabyDokument3 SeitenBoy: - 2. Bus: - 3. Box: - 4. Mouse: - 5. Child: - 6. BabyMurni Abu BakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asthalin InhalerDokument5 SeitenAsthalin InhalerRajib MandalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Studies (Levodopa, Ropinirole, Rivastigmine Tatrate, Glucerna)Dokument12 SeitenDrug Studies (Levodopa, Ropinirole, Rivastigmine Tatrate, Glucerna)KBDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ulcerative Colitis 1. Chief ComplaintDokument5 SeitenUlcerative Colitis 1. Chief Complaintdrnareshkumar3281Noch keine Bewertungen

- Post Partum HemorrhageDokument40 SeitenPost Partum HemorrhageGita GirsangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ch02 Costing Out Nursing ServicesDokument26 SeitenCh02 Costing Out Nursing ServicesRicardo CanalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comfort Room PDFDokument1 SeiteComfort Room PDFPixaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSN FP6216 ForsythKathryn Assessment4 2Dokument6 SeitenMSN FP6216 ForsythKathryn Assessment4 2NbiNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Documents Do You Need After A Blood Transfusion?: BT Checklist 1Dokument5 SeitenWhat Documents Do You Need After A Blood Transfusion?: BT Checklist 1Edelweiss Marie CayetanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cleft Lip and PalateDokument2 SeitenCleft Lip and PalateTracy100% (1)

- Dentinogenesis ImperfectaDokument4 SeitenDentinogenesis Imperfectamirfanulhaq100% (1)

- Koo Quay Keong V Ooi Peng Jin London Lucien (2016) 5 SLR 0130Dokument16 SeitenKoo Quay Keong V Ooi Peng Jin London Lucien (2016) 5 SLR 0130a b cNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cerumen Management PDFDokument10 SeitenCerumen Management PDFHimawan WidyatmikoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual of Basic Techniques For A Health Laboratory (Part1) - WHODokument114 SeitenManual of Basic Techniques For A Health Laboratory (Part1) - WHOcholinchuchuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Times Leader 03-17-2013Dokument77 SeitenTimes Leader 03-17-2013The Times LeaderNoch keine Bewertungen

- GLUMODokument8 SeitenGLUMOZhayree R.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cesarean SectionDokument73 SeitenCesarean Sectionkalsoom sahibzadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clostridium Difficile Infection and Fecal BacteriotherapyDokument9 SeitenClostridium Difficile Infection and Fecal BacteriotherapyAnonymous nEC4alrPjGNoch keine Bewertungen