Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Establishment and Opposition of the Malayan Union

Hochgeladen von

Nigel LewOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Establishment and Opposition of the Malayan Union

Hochgeladen von

Nigel LewCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The establishment of the Federation of Malaya In January 1946 the British government published proposals for a Malayan Union,

which would unite the whole of the peninsula (except Singapore, which was to become a separate colony) under a governor and a strong central government, and which considerably curtailed the authority of the rulers and the states. These proposals were strongly resisted by the Malays, who rapidly formed a political organization, the United Malay National Organization, with branches all over the country. Their attitude was supported by a group of retired Malayan civil servants in England, including Frank Swettenham, and the scheme for a Malayan Union was abandoned. In its place the Federation of Malaya Agreement was signed in Kuala Lumpur on 21 January 1948, and came into force on 1 February of that year. This agreement provided for a high commissioner and a federal legislative council containing 75 members, 50 of whom were unofficial. A considerable degree of authority was restored to the rulers, acting in consultation with their state executive councils, and a form of common citizenship was created for all who acknowledged Malaya as their permanent home and the object of their undivided loyalty. Within this framework the settlements of Penang and Malacca remained British territory, and Singapore became a separate colony under its own governor. ___________________________________________________________________________ THE Malayan Union, which the British Labour Government inaugurated in post-war Malaya on April 1, 1945, lasted slightly more than two years. Although it was a shortlived constitutional experiment, it led to dramatic political developments. In present-day Malaysian history textbooks, the Malayan Union is regarded as having awakened political activity, and heightened ethnic consciousness and nationalism among the peninsulas different ethnic groups. For the Malays, their opposition to the Malayan Union led to the birth of the United Malays National Organisation or Umno which was inaugurated on May 11, 1946 in Johor Baru and the emergence of Datuk Onn Jaafar as its first president. Umno obtained support from all strata of Malay society in opposing the Malayan Union the aristocrats, the radical Parti Kebangsaan Melayu Malaya (Malay Nationalist Party or MNP), Islamic groups, civil servants, rural leaders like the penghulus (village heads), and even the police and ex-service personnel. Umno opposed the Malayan Union because it restricted the Malay rulers powers and Malay special privileges, and granted citizenship and equal rights to non-Malays who qualified on birth, residential and other terms. Umno demanded a return to the prewar political structures, set up in the Malay states according to treaties signed with the Malay rulers under which the British protected the Malay states and advised the rulers in all matters except Islam and Malay customs. The protests and demonstrations against the Malayan Union saw Malay women breaking tradition by joining marches and carrying placards. Many Malays wrapped white cloth around their songkok (cap) as a symbol of mourning. Umno urged Malay civil servants to boycott the Malayan Union government by refusing to carry out any work. Also at Umnos

urging, the Malay rulers boycotted Sir Edward Gents inauguration as Malayan Union governor. Non-Malays were also prompted to fight for their rights, and organised political parties such as the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC) and the Malayan Democratic Union, which came under an umbrella organisation the All-Malaya Council of Joint Action (AMCJA) headed by prominent Chinese leader Tan Cheng Lock. Several trade unions and womens groups aligned with the then semi-legal Communist Party of Malaya also joined the AMCJA. For the first time, politics during the Malayan Union led to the formation of a multi-racial alliance between the non-Malay AMCJA and the Malay-based Pusat Tenaga Raayat (Putera), a coalition under the MNPs leadership that comprised its youth and women wings, and Malay cultural bodies. Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy became Putera-AMCJA president, with Tan as deputy president. This followed the MNPs departure from Umno over differences regarding Umnos flag. The MNP decided to team up with the AMCJA to fight for an independent United Malaya with equal citizenship for all, and an elected Parliament in which the Malay rulers would become constitutional monarchs. The coalitions parties also agreed that Malay would be the national language, and all citizens would be known as Melayu nationals. The proposed Melayu nationality was controversial, but it was quite different from bangsa Melayu and was not a racial but a national identity. The Malays opposed the term Malayan because it was associated with the Malayan Union, so Puteras non-Malay partners agreed not to use it. At the same time, the term Malaysian did not yet exist. The AMCJA-Putera Peoples Constitution which incorporated these points was a blueprint for Malayas future. Many observers were surprised that Chinese and pro-communist groups were willing to make such major concessions to accommodate the MNPs Malay nationalism, and equally surprised that the MNP was willing to accept non-Malays as equal citizens if they demonstrated their loyalty to Malaya. However, the British government rejected the AMCJA-Putera proposals, and decided to concede instead to the demands of Umno and the Malay rulers. The British were not yet ready to grant self-government and independence and attempted to negotiate a deal that would not endanger its political, economic and military interests. Umno and the Malay rulers had taken up their grievances with the Colonial Office in London by writing petitions to British members of Parliament and waging a public relations campaign. They received support from prominent former British government officers like Sir Richard Winstedt and Sir Frank Swettenham.

The British finally agreed to the Malay demands for the return of sovereignty to the Malay rulers, and a tightening of citizenship laws for Chinese, Indians and others. In return, Umno and the Malay rulers agreed to the British proposal to set up the Federation of Malaya as a mutually acceptable frame of government to replace the Malayan Union. ___________________________________________________________________________ The citizenship of Malayan Union Malayan Union introduced equal rights to those who want Malayan nationality. Thus, many people will become Malayan citizens. People who were born in any British Malaya or Singapores states will automatically become the citizens of Malaya if they were living there before 15 February 1942, born outside British Malaya or the Straits Settlements only if their fathers were citizens of the Malayan Union and those who reached 18 years old and who had lived in British Malaya or Singapore, 10 out of 15 years before 15 February 1942. People who want citizenship and eligible for the application must possess good characteristics and fluent in English or Malay. Furthermore, they had to take an oath of allegiance to the Malayan Union. The reduction of Sultans power The genuine ruler of Malaya known as Sultan will be put aside. Their power will be greatly reduced. Sir Edward Gent is the governor of Malayan Union. The State Councils will be administered by British Residents results in the political status of the Sultans will decrease. Formation of the Malayan Union On April 1, 1946, the Malayan Union officially came into existence with Sir Edward Gent as its governor. The capital of the Union was Kuala Lumpur. The idea of the Union was first expressed by the British on October 1945 (plans had been presented to the War Cabinet as early as May 1944 in the aftermath of the Second World War by the British Military Administration. Sir Harold MacMichael was assigned the task of gathering the Malay state rulers' approval for the Malayan Union in the same month. In a short period of time, he managed to obtain all the Malay rulers approval. The reasons for their agreement, despite the loss of political power that it entailed for the Malay rulers, has been much debated; the consensus appears to be that the main reasons were that as the Malay rulers were of course resident during the Japanese occupation, they were open to the accusation of collaboration, and that they were threatened with dethronement. Hence the approval was given, though it was with utmost reluctance. The Malayan Union gave equal rights to people who wished to apply for citizenship. It was automatically granted to people who were born in any state in British Malaya or Singapore and were living there before 15 February 1942, born outside British Malaya or the Straits Settlements only if their fathers were citizens of the Malayan Union and those who reached 18 years old and who had lived in British Malaya or Singapore "10 out of 15 years before 15 February 1942". The group of people eligible for application of citizenship had to live in Singapore or British Malaya "for 5 out of 8 years preceding the application", had to be of good character, understand and speak the English or Malay language and "had to take an oath of allegiance to the Malayan Union".

The Sultans, the traditional rulers of the Malay states, conceded all their powers to the British Crown except in religious matters. The Malayan Union was placed under the jurisdiction of a British Governor, signalling the formal inauguration of British colonial rule in the Malay peninsula. Moreover, even though State Councils were still kept functioning in the former Federated Malay States, it lost the limited autonomy that they enjoyed as they administered some local and less important aspects of government and the Federal government in Kuala Lumpur controlling vital aspects. State Councils became an extended hand of the Federal government that had to do its bidding. Also, British Residents replacing the Sultans as the head of the State Councils meant that the political status of the Sultans were greatly reduced. Opposition, dissolution of the Malayan Union and the creation of the Federation of Malaya The Malays generally opposed the creation of the Union. The opposition was due to the methods Sir Harold MacMichael used to acquire the Sultans' approval, the reduction of the Sultans' powers, and the granting of citizenship to non-Malay immigrants and their descendants-especially the ethnic Chinese, not only because of their racial and religious difference but also because their economic dominance was seen as a threat to the Malays. The United Malays National Organization or UMNO, a Malay political association formed by Dato' Onn bin Ja'afar on March 1, 1946, led the opposition against the Malayan Union. Malays also wore white bands around their heads, signifying their mourning for the loss of the Sultans' political rights. However, ex-Malayan government officials criticised the way these constitutional reforms were brought about in Malaya, even saying that it went against the principles of the Atlantic Charter. They also encouraged Malay opposition to the Malayan Union. The fact that people were allowed to hold dual nationalities meant there was a possibility that the Chinese and Indians would be loyal to their home country, rather than Malaya. After the inauguration of the Malayan Union, the Malays, under UMNO, continued opposing the Malayan Union. They utilised civil disobedience as a means of protest by refusing to attend the installation ceremonies of the British governors. They had also refused to participate in the meetings of the Advisory Councils, hence Malay participation in the government bureaucracy and the political process had totally stopped. The British had recognised this problem and took measures to consider the opinions of the major races in Malaya before making amendments to the constitution. The Malayan Union ceased to exist in January, 1948. It was replaced by the Federation of Malaya.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Fate of the Land Ko nga Akinga a nga Rangatira: Maori political struggle in the Liberal era 1891–1912Von EverandThe Fate of the Land Ko nga Akinga a nga Rangatira: Maori political struggle in the Liberal era 1891–1912Noch keine Bewertungen

- Maori and the State: Crown–Maori Relations in New Zealand/Aotearoa, 1950–2000Von EverandMaori and the State: Crown–Maori Relations in New Zealand/Aotearoa, 1950–2000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Formation of The Malayan UnionDokument2 SeitenFormation of The Malayan Unionakmal_JLXNoch keine Bewertungen

- SabbathDokument29 SeitenSabbathlyanca majanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Malayan Union, Putera-Amcja and The People's Constitution, Cheah Boon Keng, SunDokument4 SeitenThe Malayan Union, Putera-Amcja and The People's Constitution, Cheah Boon Keng, SunMala KahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Malayan Union Was ObjectedDokument2 SeitenWhy Malayan Union Was ObjectedPrashand NinozNoch keine Bewertungen

- L11 Malayan Union 1946Dokument15 SeitenL11 Malayan Union 1946Vishal SidhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- MALAYAN UNION AND FEDERATION OF MALAYADokument8 SeitenMALAYAN UNION AND FEDERATION OF MALAYAMohd Azmi ArifinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contest and Contestant MalayaDokument49 SeitenContest and Contestant MalayaSaminathan MunisamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jus SoliDokument32 SeitenJus SoliEjan LancerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malayan UnionDokument2 SeitenMalayan Unionmsokenu100% (1)

- Communist Insurgency in MalayaDokument21 SeitenCommunist Insurgency in MalayaCruise_IceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federation of Malaya: Persekutuan Tanah Melayu (PTM)Dokument22 SeitenFederation of Malaya: Persekutuan Tanah Melayu (PTM)Cruise_IceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nota Malayan UnionDokument9 SeitenNota Malayan UnionWong Chun KitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federation of MalayaDokument6 SeitenFederation of MalayaQues LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Updated) Chapter 1.5 - Malayan UnionDokument53 Seiten(Updated) Chapter 1.5 - Malayan UnionThanh TrầnNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Formation of The Federation of MalayaDokument16 SeitenThe Formation of The Federation of MalayaSekolah Menengah Rimba90% (10)

- British Reaction To Malay OppositionDokument16 SeitenBritish Reaction To Malay OppositionUmmu DhaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- MPW 2133 - The Struggle For IndependenceDokument22 SeitenMPW 2133 - The Struggle For IndependenceJayross Koi50% (2)

- Malaysia (1957-2000) 2023 Lectures 12-13Dokument24 SeitenMalaysia (1957-2000) 2023 Lectures 12-13Shoots den BrahNoch keine Bewertungen

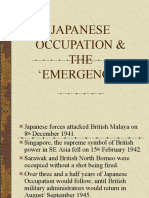

- Japanese Occupation & THE Emergency'Dokument15 SeitenJapanese Occupation & THE Emergency'farahnormiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malaysian Studies Assignment 1Dokument10 SeitenMalaysian Studies Assignment 1Kai Jie100% (1)

- The Federal Constitution - NUSRAH (1221488)Dokument2 SeitenThe Federal Constitution - NUSRAH (1221488)nusrah rahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50 Years of Constitutional Government in MalaysiaDokument11 Seiten50 Years of Constitutional Government in MalaysiaPKMB1-0618 Jong Xiao WeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Implication of British Colonization Towards The Federal ConstitutionDokument3 SeitenImplication of British Colonization Towards The Federal ConstitutionFarah ArdiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- MALAYSIAN PERCEPTIONS OF CHINA EXAMINEDDokument13 SeitenMALAYSIAN PERCEPTIONS OF CHINA EXAMINEDDANIEL BENITEZ FIGUEROANoch keine Bewertungen

- Independence of Malaya and The Formation of MalaysiaDokument8 SeitenIndependence of Malaya and The Formation of Malaysiaman_dainese100% (14)

- Chapter 2 (Background and History of Malaysia)Dokument9 SeitenChapter 2 (Background and History of Malaysia)Nur AlisharNoch keine Bewertungen

- SYSTEMS AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN MALAYSIADokument16 SeitenSYSTEMS AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN MALAYSIAJeremyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1948 and The Cold War in Malaya: Samplings of Malay ReactionsDokument25 Seiten1948 and The Cold War in Malaya: Samplings of Malay ReactionsCheAzahariCheAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 Historical Background of Malaysia Part 2Dokument32 SeitenChapter 3 Historical Background of Malaysia Part 2Dharshica MohanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 6 - The Malayan UnionDokument30 SeitenLecture 6 - The Malayan UnionRajen RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- POLITICAL TESTAMENT BETWEEN UMNO, MCA & MICDokument12 SeitenPOLITICAL TESTAMENT BETWEEN UMNO, MCA & MICKhairil Anwar MuhajirNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOPIK 5 (Modified)Dokument33 SeitenTOPIK 5 (Modified)Manimaran a/l Vadivelu JHEPNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Struggle For IndependenceDokument93 SeitenThe Struggle For IndependenceSammie PingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explain The Problem of Racial Unity in The Country After The Independence of MalaysiaDokument14 SeitenExplain The Problem of Racial Unity in The Country After The Independence of MalaysiaFarhan Sheikh MuhammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Of A NationDokument6 SeitenOf A NationSalman FarisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bahan Pameran - Menuju KemerdekaanDokument6 SeitenBahan Pameran - Menuju KemerdekaansszmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tun Tan Cheng Lock: Home News Room About Us Join Us Download Zone Contact Us About MCA About MCA Youth About Wanita MCADokument20 SeitenTun Tan Cheng Lock: Home News Room About Us Join Us Download Zone Contact Us About MCA About MCA Youth About Wanita MCAAnip AbuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historical Background of Malaysian ConstitutionDokument19 SeitenHistorical Background of Malaysian ConstitutionNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malaya_case_studyDokument29 SeitenMalaya_case_studyshanddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- MALAYSIA (AutoRecovered)Dokument2 SeitenMALAYSIA (AutoRecovered)Lucky KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Assignment: Semester Jun - Oktober 2018Dokument14 SeitenIndividual Assignment: Semester Jun - Oktober 2018Space WarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kronologi Pembentukan MalaysiaDokument1 SeiteKronologi Pembentukan MalaysiaFaridil FikriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malaysian Studies Chapter2 030306Dokument8 SeitenMalaysian Studies Chapter2 030306Nur Khairunnisa MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tamil United Liberation Front - General Election Manifesto 1977Dokument18 SeitenTamil United Liberation Front - General Election Manifesto 1977SarawananNadarasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assigment For MPWDokument7 SeitenAssigment For MPW900109-13-5069100% (1)

- Malaysian Culture Uuw 235: Lecturer: Associate Prof. Dr. Mohd Mizan AslamDokument14 SeitenMalaysian Culture Uuw 235: Lecturer: Associate Prof. Dr. Mohd Mizan AslamsuleimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formation of Malaysia's First GovernmentDokument35 SeitenFormation of Malaysia's First GovernmentHazwani HusinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group AssignmentDokument18 SeitenGroup Assignmentmnmd199Noch keine Bewertungen

- MALAYSIAN STUDIES The Struggle For IndependenceDokument97 SeitenMALAYSIAN STUDIES The Struggle For Independencehakim_956980% (5)

- Term 2 Essay AssignmentDokument4 SeitenTerm 2 Essay AssignmentRachel Anne PreeceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malaysian Legal System and Application of English Common LawDokument4 SeitenMalaysian Legal System and Application of English Common LawMouri RanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Malaysia's Constitutional EvolutionDokument13 SeitenUnderstanding Malaysia's Constitutional EvolutionChina WeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Towards Independence: Uwtv Watermark ID LogoDokument26 SeitenTowards Independence: Uwtv Watermark ID LogoMichelle TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asean AustraliaDokument10 SeitenAsean Australianurathirah ramliNoch keine Bewertungen

- GeEng 1 - Research (Singapore)Dokument3 SeitenGeEng 1 - Research (Singapore)MÁYÔRÄ YÄPNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary History of MalaysiaDokument5 SeitenSummary History of Malaysialucinda_johannesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malaysia: Merdeka Square Kuala LumpurDokument2 SeitenMalaysia: Merdeka Square Kuala LumpurRosmaliza AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11 MalaysiaDokument17 SeitenChapter 11 MalaysiaAlicia LizardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coca Cola Vs GomezDokument2 SeitenCoca Cola Vs Gomezyannie11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pilgrim Pursuit of HappinessDokument76 SeitenPilgrim Pursuit of Happinessbjtuttle100% (1)

- Corporate BylawsDokument4 SeitenCorporate BylawsRocketLawyer100% (4)

- MendicancyDokument46 SeitenMendicancyLoueljie Antigua100% (2)

- 2017 Chan Last Minute TipsDokument45 Seiten2017 Chan Last Minute TipsEdz Votefornoymar Del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The State of Emergency in Ethiopia: Compatibility To International Human Rights ObligationsDokument16 SeitenThe State of Emergency in Ethiopia: Compatibility To International Human Rights ObligationsBewesenu50% (2)

- Republic v. EspinosaDokument1 SeiteRepublic v. EspinosaJerry Cane100% (1)

- Memorandum Order No 247Dokument2 SeitenMemorandum Order No 247madamcloudnineNoch keine Bewertungen

- RP V Sandiganbayan, Ramas, DimaanoDokument3 SeitenRP V Sandiganbayan, Ramas, DimaanoTony TopacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Land Titles And Deeds Case Digest: Carino V. Insular Government (1909Dokument20 SeitenLand Titles And Deeds Case Digest: Carino V. Insular Government (1909Janet Tal-udanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1331 Federal QuestionDokument132 Seiten1331 Federal QuestionJames Copley100% (1)

- 1463 Jesus V AyalaDokument2 Seiten1463 Jesus V AyalabubblingbrookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of Popular MovementsDokument6 SeitenRise of Popular MovementsRamita Udayashankar91% (11)

- ILO ConstitutionDokument30 SeitenILO ConstitutionMajid KianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malaysian ConstitutionDokument25 SeitenMalaysian Constitutionmusbri mohamed93% (14)

- Reflecting Political and Social Menace in NigeriaDokument6 SeitenReflecting Political and Social Menace in NigeriaKAYODE OLADIPUPONoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines for issuing income & asset certificate to EWSDokument6 SeitenGuidelines for issuing income & asset certificate to EWSpiyuah aroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- NB Statement of Claim FINALDokument29 SeitenNB Statement of Claim FINALMarie DaigleNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1987 Ethiopia ConstitutionDokument3 Seiten1987 Ethiopia ConstitutionMenilek AlemsegedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chamber of Real Estate and Builders' Assoc. Vs Hon. Exec. Sec. Alberto RomuloDokument2 SeitenChamber of Real Estate and Builders' Assoc. Vs Hon. Exec. Sec. Alberto RomuloRhea Mae Lasay-Sumpiao100% (1)

- Telebap v. Comelec (1998)Dokument3 SeitenTelebap v. Comelec (1998)Carlo MercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic Vs AFP DigestDokument1 SeiteRepublic Vs AFP DigestTyrone HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Inclusion Policies and Practices in Nepal by Om Gurung 2009Dokument15 SeitenSocial Inclusion Policies and Practices in Nepal by Om Gurung 2009Deepak Kumar KhadkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- P.A. Inamdar & Ors Vs State of Maharashtra & Ors On 12 August, 2005Dokument42 SeitenP.A. Inamdar & Ors Vs State of Maharashtra & Ors On 12 August, 2005Pritha SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Beginning of The Gay Rights Movement: Gay Right Movements Since The Mid-20Th CenturyDokument3 SeitenThe Beginning of The Gay Rights Movement: Gay Right Movements Since The Mid-20Th CenturydriparuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jinnah's Works and Career As ALegislator (1921-1929)Dokument17 SeitenJinnah's Works and Career As ALegislator (1921-1929)Fayyaz AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life & Works of Rizal ModuleDokument66 SeitenLife & Works of Rizal ModulePsyche Ocol DeguitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Akshay Jain EssayDokument2 SeitenAkshay Jain EssaySasank TippavarjulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masikip V City of PasigDokument1 SeiteMasikip V City of PasigBen Dover McDuffinsNoch keine Bewertungen