Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Allomorph Selection and Lexical Preferences in Judeo-Spanish - Travis G. Bradley

Hochgeladen von

Pablo Carrión ARGOriginaltitel

Copyright

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Allomorph Selection and Lexical Preferences in Judeo-Spanish - Travis G. Bradley

Hochgeladen von

Pablo Carrión ARGCopyright:

Allomorph Selection and Lexical Preferences in Judeo-Spanish Travis G.

Bradley, UC Davis Migration is known to favor the creation of weak ties within social networks, which can in turn promote linguistic change (Milroy & Milroy 1985, Milroy 1987). Despite conventional descriptions as conservative and archaic, Judeo-Spanish (JS) shows many innovations vis--vis Modern Spanish (MS) due to dialect mixing and competition among variant linguistic forms that arose in Sephardic communities after their expulsion from Spain in 1492 (Penny 1992, 2000). The present study analyzes two such cases of variation in phonologically conditioned allomorphy. One consequence of dialect mixing was competition between variants from central areas of the Peninsula in which Latin tonic // and // had given rise to diphthongs [je] and [we] and those from lateral areas which preserved the monophthongs (Penny 1992:253, 2000:188-9). In many cases, variation can be observed within the same lexeme and the same dialect. The JS forms in (1a,b) show free variation between diphthongs and mid vowels, where the corresponding MS forms show only the diphthong. In other cases, as seen in (2a,b), an innovative alternation has been introduced in JS words whose Latin etymon did not contain tonic // or // and whose MS correspondents show only mid vowels. For some speakers, the vacillation between diphthongs and mid vowels has led to the analogical extension of [je] and [we] to morphologically derived words. The JS forms in (3a,b) have the diphthong regardless of stress, whereas the MS forms show an alternation between stressed diphthongs and unstressed mid vowels. Recent work in Optimality Theory has proposed that surface allomorphs are derived not from a common underlier but from an ordered set of allomorphs in the input (Bonet et al 2007). The constraint in (4a) demands faithfulness to the lexically specified ordering and favors the least marked allomorph. I adopt the constraint in (4b) as an informal label for whatever contextsensitive markedness constraints favor diphthongs in tonic syllables (Bermdez-Otero 2007:285; see also Holt 2007:384-5). I propose an account of the free variation in JS (1) in which (i) mid vowels are ordered above diphthongs in the set of input allomorphs, e.g., /d{e1>je2}nt-i/, and (ii) the constraints PRIORITY and TONICDIPHTHONGAL are variably ranked. When markedness dominates, the diphthong is optimal in stressed syllables (5c), while the opposite ranking favors the mid vowel (5e). High-ranking IDENT ensures phonological faithfulness within allomorphs by ruling out the e1je1 and je2e2 mappings in (5b,f) and (5d,h), respectively. The same analysis covers the data in (2) on the assumption that the JS speakers in question have extended the {mid vowel>diphthong} ordering to novel lexemes whose etyma lacked tonic // and //, e.g., /k{e1>je2}z-u/. Finally, the fixed ranking of TONICDIPHTHONGAL PRIORITY in MS derives the alternation between [djnte] (6c) and [dentsta] (6e). Although not shown here, the ranking of IDENT TONICDIPHTHONGAL is necessary in MS to preserve input mid vowels in non-alternating forms, e.g., terco, *tierco stubborn ~ terquedad stubbornness. JS speakers who level the alternation in (3a,b) have simply eliminated mid vowels from the set of input allomorphs for the relevant lexemes, rendering PRIORITY irrelevant. IDENT preserves the input diphthongs in [djnti] (7b) and [djentsta] (7d). The second case of phonologically conditioned allomorphy in JS involves diminutive suffixation. There was competition among variant suffixes in the 16th century, but by the 18th century iko/a had come to predominate, subject to certain phonological restrictions (Bunis 2003). For example, the preferred suffix iko/a appears when the final consonant of a stem is non-dorsal (8a), but after dorsals ito/a appears instead (8b). I propose that these allomorphic preferences are encoded in the lexical ordering {ik1>it2} and that the alternation in present-day JS is driven by the fixed ranking of (9) above PRIORITY. The preferred allomorph surfaces in (10a) but is blocked in (10e) by OCP(DOR), whereby the next best allomorph emerges as optimal in (10g). The ranking of IDENT OCP(DOR) is necessary to preserve input /k/ in non-alternating suffixes, e.g., JS monarka monarch ~ monarkiko, *monarkito monarchist.

(1) (2) (4)

a. b. a. b. a.

JS MS JS djnti ~ dnti djnte tooth (3) a. djnti kwpu ~ kpu kwpu body djentsta kzu ~ kjzu kso cheese b. bwnu plvu ~ pwlvu plo dust bwend PRIOR(ITY) Bonet et al (2007:906) Respect lexical priority (ordering) of allomorphs. b. T(ONIC)D(IPHTHONGAL) Bermdez-Otero (2007:285) Diphthongs are favored in stressed syllables.

MS djnte dentsta bwno bond

tooth dentist good goodness

(5) /d{e1>je2}nt-i/ IDENT TD PRIOR a. d1nti *! b. dj1nti *! c. dj2nti * d. d2nti *! * * (6) /d{e1>je2}nt-e/ IDENT TD PRIOR a. d1nte *! b. dj1nte *! c. dj2nte * d. d2nte *! * * (7) /djent-i/ IDENT TD PRIOR a. dnti *! * (n/a) b. djnti (n/a) (8)

/d{e1>je2}nt-i/ IDENT PRIOR TD e. d1nti * f. dj1nti *! g. dj2nti *! h. d2nti *! * * /d{e1>je2}nt-ista/ IDENT TD PRIOR e. de1ntsta * f. dje1ntsta *! * g. dje2ntsta * *! h. de2ntsta *! * * /djent-ista/ IDENT TD PRIOR c. dentsta *! * (n/a) d. djentsta * (n/a)

(9)

a. lto altko tall kamno kaminko path rza rizka laugh pao paako bird b. blko blakto, *blakko white ma mita, *mika crumb fwa fawta, *fawka forge OCP(DOR) Avoid adjacent segments on the consonantal tier that are identical in DORSAL place. /blak-{ik1>it2}-o/ IDENT OCP PRIOR e. blakk1o *! f. blakt1o *! g. blakt2o * h. blakk2o *! * *

(10) /alt-{ik1>it2}-o/ IDENT OCP PRIOR a. altk1o b. altt1o *! c. altt2o *! d. altk2o *! *

Selected References Bonet, Eullia, Maria-Rosa Lloret, & Joan Mascar. 2007. Allomorph selection and lexical preferences: Two case studies. Lingua 117.903-927. Bunis, David. 2003. Ottoman Judezmo diminutives and other hypocoristics. Linguistique des langues juives et linguistique gnrale, 193-246. Paris: CNRS ditions. Penny, Ralph. 1992. La innovacin fonolgica del judeoespaol. Actas del II Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Lengua Espaola. Tomo II, 251-257. Madrid: Pabelln de Espaa.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Bible Translations Into Sanskrit - WikipediaDokument2 SeitenBible Translations Into Sanskrit - WikipediaPablo Carrión ARG100% (1)

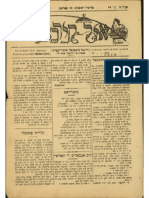

- La Renesansa Djudea 1927 - April 29thDokument1 SeiteLa Renesansa Djudea 1927 - April 29thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taking Community Seriously? Communitarian Critiques of Liberalism - Aneta GawkowskaDokument16 SeitenTaking Community Seriously? Communitarian Critiques of Liberalism - Aneta GawkowskaPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communitarianism As The Social and Legal Theory Behind The German Constitution - Winfried BruggerDokument30 SeitenCommunitarianism As The Social and Legal Theory Behind The German Constitution - Winfried BruggerPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gazeta de Amsterdam 1672 - Sept 12thDokument1 SeiteGazeta de Amsterdam 1672 - Sept 12thCurso De Ladino Djudeo-EspanyolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verdict Handwritten by Rabbi Aharon Katz of Paderborn (Soletreo)Dokument1 SeiteVerdict Handwritten by Rabbi Aharon Katz of Paderborn (Soletreo)Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Descriptive Sumerian GrammarDokument777 SeitenA Descriptive Sumerian GrammarAsier Basagoiti100% (3)

- Sumerian in A NutshellDokument13 SeitenSumerian in A NutshellPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sumerian GrammarDokument215 SeitenSumerian GrammarBaskar Saminathnan100% (18)

- A Sheet of Livorno Haggadah 1838 Hebrew and Ladino (Katz Center Library)Dokument1 SeiteA Sheet of Livorno Haggadah 1838 Hebrew and Ladino (Katz Center Library)Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Trezoro Newspaper Cover Bulgaria 1894Dokument1 SeiteEl Trezoro Newspaper Cover Bulgaria 1894Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Pountchon 1925 - April 24thDokument1 SeiteEl Pountchon 1925 - April 24thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ladino Translation of Festival Prayer Book Written in Oriental Cursive Hand Soletreo (Palestine, 18th Century)Dokument1 SeiteLadino Translation of Festival Prayer Book Written in Oriental Cursive Hand Soletreo (Palestine, 18th Century)Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Postal Soletreo Ladino 1938Dokument1 SeitePostal Soletreo Ladino 1938Curso De Ladino Djudeo-Espanyol100% (1)

- El Primo Bezo 1922 (Portada-Cover)Dokument1 SeiteEl Primo Bezo 1922 (Portada-Cover)Curso De Ladino Djudeo-EspanyolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Esther Scroll From The Ottoman EmpireDokument1 SeiteEsther Scroll From The Ottoman EmpirePablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Pountchon 1910 - March 17thDokument1 SeiteEl Pountchon 1910 - March 17thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mesadjero 1938 - February 17thDokument1 SeiteMesadjero 1938 - February 17thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Kirbatch 1911 February 24thDokument1 SeiteEl Kirbatch 1911 February 24thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Kirbatch 1911 March 24thDokument1 SeiteEl Kirbatch 1911 March 24thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Pountchon 1925 - May 8thDokument1 SeiteEl Pountchon 1925 - May 8thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Pountchon 1925 - May 22thDokument1 SeiteEl Pountchon 1925 - May 22thPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Pountchon 1925 - May 1stDokument1 SeiteEl Pountchon 1925 - May 1stPablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bitolya Ladino Jewish Club Flyer 1917Dokument1 SeiteBitolya Ladino Jewish Club Flyer 1917Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- .Ar - Prosodically-Conditioned Sibilant Voicing in Balkan Judeo-Spanish - Travis G. BradleyDokument13 Seiten.Ar - Prosodically-Conditioned Sibilant Voicing in Balkan Judeo-Spanish - Travis G. BradleyCurso De Ladino Djudeo-EspanyolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Almanac Israelite, Thessaloniki 1923 (Portada-Cover)Dokument1 SeiteAlmanac Israelite, Thessaloniki 1923 (Portada-Cover)Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hebreos Católicos: Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos en Ladino Djudeo-EspanyolDokument5 SeitenHebreos Católicos: Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos en Ladino Djudeo-EspanyolHebreos Católicos de ArgentinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ladino Translation of Festival Prayer Book Written in Oriental Cursive Hand Soletreo (Palestine, 18th Century)Dokument1 SeiteLadino Translation of Festival Prayer Book Written in Oriental Cursive Hand Soletreo (Palestine, 18th Century)Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meam Loez (Sefer Bereshit Complete Edition)Dokument596 SeitenMeam Loez (Sefer Bereshit Complete Edition)Pablo Carrión ARG80% (5)

- El Trezoro Newspaper Cover Bulgaria 1894Dokument1 SeiteEl Trezoro Newspaper Cover Bulgaria 1894Pablo Carrión ARGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Sosai Masutatsu Oyama - Founder of Kyokushin KarateDokument9 SeitenSosai Masutatsu Oyama - Founder of Kyokushin KarateAdriano HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bakhtar University: Graduate School of Business AdministrationDokument3 SeitenBakhtar University: Graduate School of Business AdministrationIhsanulhaqnooriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Revised ResearchDokument35 SeitenFinal Revised ResearchRia Joy SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lean Foundation TrainingDokument9 SeitenLean Foundation TrainingSaja Unķnøwñ ĞirłNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anschutz Nautopilot 5000Dokument4 SeitenAnschutz Nautopilot 5000Văn Phú PhạmNoch keine Bewertungen

- HED - PterygiumDokument2 SeitenHED - Pterygiumterry johnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- HiaceDokument1 SeiteHiaceburjmalabarautoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TAFJ-H2 InstallDokument11 SeitenTAFJ-H2 InstallMrCHANTHANoch keine Bewertungen

- Script For The FiestaDokument3 SeitenScript For The FiestaPaul Romano Benavides Royo95% (21)

- Engaged Listening Worksheet 3 - 24Dokument3 SeitenEngaged Listening Worksheet 3 - 24John BennettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visual AnalysisDokument4 SeitenVisual Analysisapi-35602981850% (2)

- Guest Speaker SpeechDokument12 SeitenGuest Speaker SpeechNorhana Manas83% (82)

- Revision and Second Term TestDokument15 SeitenRevision and Second Term TestThu HươngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecological Modernization Theory: Taking Stock, Moving ForwardDokument19 SeitenEcological Modernization Theory: Taking Stock, Moving ForwardFritzner PIERRENoch keine Bewertungen

- Drama For Kids A Mini Unit On Emotions and Character F 2Dokument5 SeitenDrama For Kids A Mini Unit On Emotions and Character F 2api-355762287Noch keine Bewertungen

- Issues and Concerns Related To Assessment in MalaysianDokument22 SeitenIssues and Concerns Related To Assessment in MalaysianHarrish ZainurinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Court of Appeals: DecisionDokument11 SeitenCourt of Appeals: DecisionBrian del MundoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guerrero vs Benitez tenancy disputeDokument1 SeiteGuerrero vs Benitez tenancy disputeAb CastilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 4 CasesDokument181 SeitenWeek 4 CasesMary Ann AmbitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Script - TEST 5 (1st Mid-Term)Dokument2 SeitenScript - TEST 5 (1st Mid-Term)Thu PhạmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Project On Employee EngagementDokument48 SeitenFinal Project On Employee Engagementanuja_solanki8903100% (1)

- 52 Codes For Conscious Self EvolutionDokument35 Seiten52 Codes For Conscious Self EvolutionSorina LutasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Analytics in Practice /TITLEDokument43 SeitenFundamentals of Analytics in Practice /TITLEAcad ProgrammerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On The Hells AngelsDokument6 SeitenResearch Paper On The Hells Angelsfvg2xg5r100% (1)

- Heat Wave Action Plan RMC 2017Dokument30 SeitenHeat Wave Action Plan RMC 2017Saarthak BadaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eng9 - Q3 - M4 - W4 - Interpret The Message Conveyed in A Poster - V5Dokument19 SeitenEng9 - Q3 - M4 - W4 - Interpret The Message Conveyed in A Poster - V5FITZ100% (1)

- TASKalfa 2-3-4 Series Final TestDokument4 SeitenTASKalfa 2-3-4 Series Final TesteldhinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class Homework Chapter 1Dokument9 SeitenClass Homework Chapter 1Ela BallıoğluNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Train Enquiry System: 12612 Nzm-Mas Garib Rath Exp Garib Rath 12434 Nzm-Mas Rajdhani Exp RajdhaniDokument1 SeiteNational Train Enquiry System: 12612 Nzm-Mas Garib Rath Exp Garib Rath 12434 Nzm-Mas Rajdhani Exp RajdhanishubhamformeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1995 - Legacy SystemsDokument5 Seiten1995 - Legacy SystemsJosé MªNoch keine Bewertungen