Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Reading Habits

Hochgeladen von

shilpaiprOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Reading Habits

Hochgeladen von

shilpaiprCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

THE READING HABIT - A MISSING LINK BETWEEN LITERACY AND LIBRARIES Angela Phillip Dept of Extension Studies, University

of Papua New Guinea

ABSTRACT It is argued that there is little point in putting energy into teaching literacy if there is no follow-up programme to establish reading habits. The U.P.N.G. Extension Studies Book Programme has highlighted three needs in relation to this: 1) the need to take the books to the people rather than waiting for the people to come to the books, 2) the need to provide books that are easy enough for people to enjoy, and 3) the need for ongoing commitment to the programme. It is argued that the the reading habit is not only a missing link between literacy and libraries, but it is a link so vital that at every level from village to university the people in PNG are drastically underachieving in their daily work. INTRODUCTION Giving someone literacy skills is rather like teaching a person to drive and then giving them only a few drops of petrol to practise with - the machine is perfect and the driving skill has been acquired but it is not yet an automatic skill because there has not been enough practice. Once the fuel runs out the driving skill becomes useless and begins to deteriorate. Giving someone the reading habit, on the other hand, involves providing a continuous supply of easily processed fuel so that the new driver can go places, can get to enjoy driving and can eventually realise the limitless possibilities it opens up. The initial step is getting the driver to appreciate what exciting new trips the fuel makes possible so that he or she will search for more fuel when the current supply runs out. In other words it is necessary to provide people with enough easily accessible interesting books for them to find reading so enjoyable that they themselves want to do more of it. This has to be achieved somehow or the newly literate will never consolidate their skills by using the libraries, because they will not know what delights lurk within. People start trying a new food or a new drink or any new experience because it becomes available in a familiar place and because it is enjoyable. People make the new food part of their regular diet if it continues to be available long enough for them to decide they do not want to do without it. It is the same with books. Once people have developed the reading habit they will come looking for the books. Until that time the libraries will stock

their shelves in vain and the literacy workers will have largely wasted their efforts. It is not only the newly literate, however, who need the reading habit in order to mentally grow and fulfil their potential. Students in PNG even after ten or more years of schooling do not often have the reading habit. This is mostly because there have never been enough suitable books around to establish the habit. Reading tends to be associated with course work and difficulty, rarely with pleasure. Whatever their discipline students cannot fulfil their potential if they do not read widely. Their general knowledge remains low and the standard of their written work remains low. To combat this problem and to enable our students to achieve better in Extension Studies at U.P.N.G. we devised a Book Programme. Its aim was to get the students reading as a part of daily life, and to establish books as a habit that would always be needed and enjoyed. The Book Programme has highlighted three main needs involved in creating book addiction. The first need is to make reading material easily available, to take the books to the people rather than wait for the people to come to the books. The second need is to provide reading material that is easy enough to be enjoyable. The third need overrides any others. It is the need for the people involved in the project to believe in the value of what they are doing. It is this belief that will generate the ongoing commitment that is needed to provide the sustained driving force necessary for the success of such projects. TAKING THE BOOKS TO THE PEOPLE Why It is much better to begin with to take books to the people than to expect people to come to libraries to look for books. There are two reasons for this. The first reason is that people do not go to libraries because it is not a culturally familar thing to do. The second reason is that if people do pluck up courage and venture through library doors they often find that it is such an alien place that they leave as soon as possible and do not come back. Almost all our valuable life-enriching habits are given to us by our parents, our peers or our teachers. The people that are culturally closest to us and who are therefore most influential are our parents and our peers. In PNG neither of these two groups are likely to lead people into libraries because they usually do not go there themselves. Even teachers are unlikely to get their students to become regular library-goers because although teachers preach the value of reading, they usually do not read much themselves, because they too were not given the gift of the reading habit. If people in PNG are lucky enough to live within reach of the few libraries that exist, they are unlikely to appreciate their luck because the library is such an alien place. It does not seem like a place to relax because you cannot chew, you cannot smoke and in most libraries you cannot even talk or laugh or sit on the floor. It seems rather like school with library guardians on the look-out for offenders. Unless a person is convinced in advance

that there is something worth coming for, he or she will most likely leave fairly quickly and avoid coming back. To most people a visit to the library would not be worth a trek through the bush or the effort of getting to a provincial centre during limited opening times. How There are of course many methods of taking books to the people. One way would be for library staff to set up market stalls. Another way would be to set up a library truck and make a mobile library which could visit the villages. With the Extension Studies Book Programme we decided the best way was to give each tutor a box of books to be taken each week into the classroom. At the beginning or end of every tutorial, students could change their books. To minimise administration for the tutor each book was provided with a card which was put in an envelope attached to the back cover. When the students borrow a book, they remove the card from the book pocket, write their name and the date and then put the card in the book box. When they return a book, they find the card, put it back in the book pocket and replace the book in the box. Points to note Extra Costs The cost of buying the books and getting them to Port Moresby had been carefully calculated and budgetted for. There were in addtion transport costs from the wharf, processing, packing and mailing costs which had either not been foreseen or else had been grossly underestimated. Despite a massive amount of help with processing from the Library and Information Studies Department and a donation of cardboard boxes to pack the books in from the F.T. Wimble Company, the strain on the already heavily stressed resources of Extension Studies was considerable. Book Loss Even before the books left Port Moresby, quite a few of them "walked". Although it was in some ways encouraging to realise that people around the university considered them worth stealing it meant that there were less books to send to the students round the country. It is too early at this point to know what the loss rate will be. It is anticipated to be fairly heavy given the frequent turnover of part-time tutors in Extension Studies and the fairly high student drop-out rate associated with distance education. Book loss, however, was not an unexpected problem and it is hoped that as the programme becomes better established and as books become more widely available there will be less misappropriation. Correct Usage

It has been difficult to ensure that the books actually stayed in the boxes and were taken to the students. There have been some reports that the books have been removed from the boxes and put prettily on shelves in locked offices. Such behaviour in relation to books is common and is caused by the book controller's addiction to orderly care of books as described below. Care of Books By far the most difficult problem to cope with emotionally for a lover of books has been the disorderly state of the book box at the end of borrowing time. The books that have been rooted through and rejected look frayed at the edges after a single session. The books that have actually been out on loan come back stained and bent and the initial reaction is to shout angrily at the borrowers and remove the books to a safe place. Librarians the world over seem to be similarly affected by an allergy to disorder as is evidenced by phenomena such as the conventional library book display, or the library seating arrangement. Books in displays, allegedly to tempt readers, are generally for looking, often not for touching, and certainly not for reading. To borrow a book shown in a book display and actually read it, it is usually necessary to go to the display armed with pen and paper and make detailed notes of title author etc. It is then necessary to come back one or two weeks later and locate it on the shelves where it will certainly be put before a prospective reader is allowed to carry it off to read. This is akin to a test, that most potential readers do not pass. Seating arrangements in libraries are another area where librarians tend to put their love of order before their desire to encourage reading. Seating is usually hard and formal and arranged at tables or in rows. In Papua New Guinea especially it would seem sensible to arrange for at least some of the seating to be informal and comfortable and possibly at floor level. It seems that poor care of books and general disorder of reading areas are aspects of getting people into the reading habit that have to be faced and accepted cheerfully. This does not mean that book care and good order should not be encouraged. It does mean that book controllers who already love books should not be angry with new readers and chase them away. PROVIDING EASY ENJOYABLE READING MATERIAL Why To be enjoyable, an activity must not be too difficult. This applies to reading as much as to any other leisure pursuit and so reading habits need to be established with easy reading material. In PNG the reading levels of the vast majority of educated people are very low. The initial reason for poor reading levels is the fact that there are generally very few

books available in PNG and in the past there were even fewer. Part of the reason they remain so low, however, is that institutions such as schools, university departments and teachers' colleges do not like to face the reality of how low the present reading proficiencies actually are. This reluctance to face the facts means that nothing is done to raise the reading levels because students at all levels tend to be given reading material that is too hard for them. In Extension Studies for example, out of a sample of 480 students who applied for entry into the matriculation programme in Semester 2 1990 only 4.2% could read independently at grade ten level. The minimum requirement before sitting the entry test for the matriculation programme is a pass at grade ten. John Herman (1988) examined the reading levels of students in post-secondary institutions and had similar findings. He found that no-one in his sample of teachers from the Inservice College could read independently at grade ten level and only one student from Gaulim Teachers College could do so. Of the sample of national high school students at Sogeri only 8% could read at grade ten level. It must be noted however that his samples were very small. A more recent study with a much larger sample, however, shows similar results. McLaughlin investigated the reading levels of 90 teachers applying for the B.Ed programme at U.P.N.G. and found that only 27% of them could read independently at grade ten level. (McLaughlin, reported in Mohok-Mclaughlin, 90) The most depressing picture of all, perhaps, is painted by Julie Mohok-McLaughlin in her study on community school teachers' reading levels. (Mohok-McLaughlin, 1990) She found that of teachers doing preservice courses at four colleges in PNG only 11% could read at grade ten level and that of a sample of teachers doing inservice courses at the Inservice College in Port Moresby, only 5% could read at grade ten level. As she said in July 1990 when presenting these findings at the TESLA Conference in Lae: "Things are sliding towards the impossible." The chosen books must then be easy enough to be read without a struggle and the content must be interesting enough to be tempting. How The best judge of the right reading level and the most interesting content is the prospective reader. For this reason books covering a range of reading levels from grade 8 to grade 12 and above were provided for the students. Both graded readers and first language texts were included. Most of the books provided were fiction. This decision was made on the assumption that most people prefer to read stories for pleasure rather than instructional texts. It is not always easy to predict what people will find interesting so once again a range of story types was included in the programme.

The programme has a monitoring component where students are asked to write very brief book reviews on the books they read and the tutor has instructions to send in the reviews at the end of each semester. In this way it is hoped to discover which are the more popular books. It is also hoped to monitor changes of interest. For example, science fiction seems to have become more interesting to PNG readers recently, possibly because of the influence of television. Points to note It is too early in the programme to assess how appropriate the difficulty and interest levels are. The reports so far are that students are reading avidly so there seem to be no major problems with choice of books although the programme does not supply enough books and it seems that students are rapidly exhausting the present supply. The monitoring system is not very reliable because there is no way to ensure that the student writes an honest review, or even that he or she writes a review at all. One way to monitor more effectively without changing the voluntary nature of the project would be to ask tutors to interview students about the books they have read but this would be unacceptably time consuming given that there is only one tutorial session each week. What is most important to note is that "a range of books" does not mean "any books". It is essential to to provide the books that the readers want to read and this is difficult for two reasons. The first is that Book Programmes often depend on Aid Agencies that find it difficult to donate specific books. It seems, however, that Aid Agencies will try to provide the books that are needed if they are adequately informed. This is the case with the Asia Foundation which is kindly supplying books for Phase Two of the Extension Studies Book Programme. The second reason is that it is very hard for the book lovers in charge of the project to accept that the books that they value are not the books that the new readers want to read. It is very hard to provide books that are considered "rubbish" in preference to books that are well written and inspiring. This is probably the hardest part of all, but it is essential that people are given freedom to find their own way into reading. They will progress by themselves if we have faith in them. After all, we did! COMMITMENT GENERATED BY BELIEF IN THE VALUE OF ENCOURAGING THE READING HABIT Why Without a core of people who are committed to encouraging the reading habit because of their belief in its value, it will not be possible to get people reading. Book projects require seemingly endless boring hard work and they need continuing financial support which often necessitates arduous exhausting begging.

How There are two ways to generate commitment to such projects. One is to make sure the project organisers are themselves addicted to reading, the other is to explain what is known about the value of encouraging the reading habit. There are two major reasons why taking people further than basic literacy skills by encouraging reading is worthwhile: one is its importance to the mental growth of the individual and the second is its importance to the economic growth of the state. Mental Growth of the Individual Many claims have been made about the mental growth associated with the acquisition of literacy skills, but these claims tend to be confused by two issues. One is the literacy definition issue. There is a need to determine exactly what being literate involves before one can claim specific effects for such a state. The second issue is the confusion between the effects of schooling and the effects of literacy. In most studies the effects of schooling have not been separated from the effects of literacy, but this fact has been largely glossed over and all cognitive gains have been imputed to the effects of literacy. Both these issues have a bearing on the most interesting question to do with the acquisition of literacy: At what point do literacy skills have a significant effect on cognitive development? There is as yet no conclusive answer to this question, mainly because of the difficulty of separating out background variables and precisely identifying stages of development, but there are some indications. The claims that literacy affects cognition have been investigated by Vygotsky (1962), Luria (1976) and more recently by Scribner and Cole (1981). Both Vygotsky and Luria found that literacy affected cognition. Scribner and Cole, however, pointed out that in the studies conducted by both these researchers as well as investigations undertaken by others, such as the work in Senegal conducted by Greenfield and Bruner (reported in Scribner and Cole, 1981) there was a failure to distinguish between the effects of literacy and schooling. In order to clarify this confusion , Scribner and Cole isolated the effects of literacy from schooling by studying the Vai people in Liberia, some of whom are literate but have never been to school. The Scribner and Cole results were interesting, but were not what they had expected. They found that schooling had the greatest overall effect on cognition and that literacy had specific minor effects which varied from one written language to another (e.g. Vai compared with Arabic). It is worth noting at this point, however, that Vai has limited uses in the society and is confined mainly to formulaic letters and records. These findings indicate that something more than basic literacy skills are needed in order for the big leap in problem-solving skills to occur. In a brief review of writing research Krashen (1984) reports five studies that show a correlation between pleasure reading and competence in writing and only one that does not. While it is not possible to come to any firm conclusions on the grounds of

correlational studies that may have many uncontrolled variables, it does seem reasonable to believe that increased practice in reading will help performance in written language. It seems that although every small step forward in the mental process of acquisition of literacy will undoubtedly have a beneficial effect on cognitive development, the most significant effect probably occurs when the literacy skills become automatic and the individual starts to move forward alone. Economic Growth of the State According to a study by Anderson & Bowman in 1966 (reported in Oxenham 1980) there is a threshold of about 40% adult literacy or of primary school enrolment needed for economic development to take place. The reasons for this are partly because the tendency to adopt innovations seems to be related to levels of literacy and education and partly because it is believed that literate people learn faster and retain longer. The Copper Mining companies in Zambia, for example, found that not only were schooled and literate people easier to train, but they were also better able to hold on to what they had learned. (Oxenham 1980) Differences in the memory patterns of literate people were also claimed by Vygotsky (1978) who believed that illiterate people tended to use "natural" memory, or what would in modern terms be called "episodic " memory (Gregg 1986), which is directly linked to personal experience rather than "semantic memory" which is a meaning network. Memory and written language are obviously vital components of the education which is needed in order to make use of new technologies and as Osser (1983) points out, it is generally agreed that educational failure is primarily to do with a child's language skills. Such awareness of the difference a schooled and literate population makes to a country's economy is at the heart of the world-wide drive towards universal literacy which has occurred only in the last 20 to 30 years despite that the fact that the written word has been around for some 5,000 years. Neither is it only developing countries that are showing concern. As recently as June 1990 a newspaper in Australia ran a long article under the headline "Work Illiteracy costs more than $3bn a year". (Bean, Weekend Australian, June 1990) Points to note There have been no problems in generating commitment to the project in our immediate work area. The project owes its success so far to people like Dr Howard Van Trease, the Director of Extension Studies, without whose support the project could not have started, as well as to people like Kevin Ahipum who is Extension Studies most lowly administrative assistant. Because Kevin believes that the project is worthwhile he has spent countless hours writing out bookcards, chasing up lost books, looking for packing materials and other such tasks in addition to his normal duties. He has personally benefitted by borrowing some of the books and he has valued this so much that he continues to give extra help to make the books available to others. These are just two

examples of people without whom the project would not work. To generate commitment further afield to set up similar projects is the work of all those in any country who share such beliefs. The responsibility rests especially with those occupying positions of power and authority, whom the people regard as their leaders. CONCLUSION It is important to encourage the reading habit so that people grow mentally and fulfil their potential at every level from village to university. Neither a subsistence farmer nor a graduate chemist can fulfil his or her potential without the cognitive growth that comes from reading widely and people will not read further than their immediate needs if they are not given the reading habit. Such growth is every person's right and will benefit the country economically as well as benefitting the individual personally. To foster such a reading habit and forge the link between people with basic literacy skills and the libraries, it is necessary for the libraries to reach out to the people. Librarians will have to take the books to the people rather than waiting for the people to come to the books if they really want the people to read. It is also necessary to provide material that is easy enough to be enjoyable so that people want to read. Librarians must learn to step out of their secure domains and get closer to the grass roots. If we give people what they want, rather than what we think they should have, they will start reading. Then the literacy skills will grow and yield fruit rather than wasting away for lack of use. Finally and most important of all it is necessary to spread the word, to create a general awareness of the importance of books to the mental growth of the individual and to the economic growth of the nation. It is necessary most of all to give books to the people, to give plenty of books which are both easy and interesting and to provide these in a manner that is culturally acceptable. Once people get the reading habit, they will pass it on, the demand for books will grow and the citizens of Papua New Guinea will start to achieve as they should. REFERENCES Bean R. 1990 Work Illiteracy costs more than $3bn a year Weekend Australian 22-24 June 1990 Gregg V.H. 1986 Introduction to Human Memory London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Herman J. 1988 ESL Reading in Post-Secondary Institutions PNG Journal of Education 24,2 1988:204-213 Krashen S. D. 1984 Writing: Research, Theory and Applications Oxford: Pergamon Luria A.R. 1976 Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press Mohok-McLaughlin J. 1990 Reading Abilities of Inservice and Preservice Teachers Unpublished B.A. Honours thesis, Dept of Lang. & Literature, U.P.N.G. Osser H. 1983 Language as an Instrument of School Socialisation: An Examination of Bernstein's Thesis In B. Bain (ed) The Sociogenesis of Language and Human Conduct New York: Plenum Press 1983:311-322 Oxenham J. 1980 Literacy: Writing, Reading and Social Organisation London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Scribner S. & M. Cole 1981 The Psychology of Literacy Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press Vygotsky L. 1962 Thought and Language Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Vygotsky L. 1978 Mind in Society Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Open Library - Center For LearningDokument28 SeitenOpen Library - Center For LearningPratham BooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beyond Books: Advice for New School LibrariansVon EverandBeyond Books: Advice for New School LibrariansBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Mommy, Teach Me to Read!: A Complete and Easy-to-Use Home Reading ProgramVon EverandMommy, Teach Me to Read!: A Complete and Easy-to-Use Home Reading ProgramBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- Material PosterDokument3 SeitenMaterial PosterccNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Seven E's of Reading for Pleasure: Alphabet Sevens, #4Von EverandThe Seven E's of Reading for Pleasure: Alphabet Sevens, #4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Benefits of ReadingDokument4 SeitenBenefits of ReadingKelly Cham100% (4)

- Beyond the Answer Sheet: Academic Success for <Br>International StudentsVon EverandBeyond the Answer Sheet: Academic Success for <Br>International StudentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guided Reading: Learn Proven Teaching Methods, Strategies, and Lessons for Helping Every Student Become a Better Reader and for Fostering Literacy Across the GradesVon EverandGuided Reading: Learn Proven Teaching Methods, Strategies, and Lessons for Helping Every Student Become a Better Reader and for Fostering Literacy Across the GradesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (36)

- Reading HabitDokument3 SeitenReading HabitReynal LwrceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arunav Golden Jubilee Year Pages 88 91Dokument4 SeitenArunav Golden Jubilee Year Pages 88 91anne hathawayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raising Readers: How to nurture a child's love of booksVon EverandRaising Readers: How to nurture a child's love of booksBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (3)

- English at WorkplaceDokument9 SeitenEnglish at WorkplaceAirani Idani0% (1)

- Reading For EnjoymentDokument44 SeitenReading For EnjoymentK MAHADEONoch keine Bewertungen

- Let Them Have Books: A Formula for Universal Reading ProficiencyVon EverandLet Them Have Books: A Formula for Universal Reading ProficiencyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Your Child to Read: A Parent's Guide to Encouraging a Love of ReadingVon EverandTeaching Your Child to Read: A Parent's Guide to Encouraging a Love of ReadingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Welcome!: ENGL 552-81 Young Adult LiteratureDokument18 SeitenWelcome!: ENGL 552-81 Young Adult LiteratureRosmery MejiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading with Babies, Toddlers and Twos: A Guide to Laughing, Learning and Growing Together Through BooksVon EverandReading with Babies, Toddlers and Twos: A Guide to Laughing, Learning and Growing Together Through BooksBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (10)

- Becoming and Being: Reflections On Teacher-LibrarianshipDokument296 SeitenBecoming and Being: Reflections On Teacher-Librarianshipualbertatldl100% (1)

- How To Develop Reading Habits in StudentsDokument4 SeitenHow To Develop Reading Habits in StudentsFaith AmosNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Commonplace Book on Teaching and Learning: Reflections on Learning Processes, Teaching Methods, and Their Effects on Scientific LiteracyVon EverandA Commonplace Book on Teaching and Learning: Reflections on Learning Processes, Teaching Methods, and Their Effects on Scientific LiteracyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group Assignment: International Islamic University Malaysia Semester I 2008/2009Dokument11 SeitenGroup Assignment: International Islamic University Malaysia Semester I 2008/2009Zulkifli ZakariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digital Access Printed Dvds Bibliographic Databases: Citation Needed Citation NeededDokument3 SeitenDigital Access Printed Dvds Bibliographic Databases: Citation Needed Citation NeededNpt VeluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation Beyond Program - LISDokument4 SeitenInnovation Beyond Program - LISMichelBorresValentinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 2A and 2B Activity and Application AnswerDokument2 SeitenLesson 2A and 2B Activity and Application AnswerNeil ApoliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Promotion ProgramDokument8 SeitenReading Promotion Programapi-295546924Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Book Whisperer: Awakening the Inner Reader in Every ChildVon EverandThe Book Whisperer: Awakening the Inner Reader in Every ChildBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (37)

- Choosing a Good Private School for Your Child: The Ultimate Guide for Parents and Guardians in ZambiaVon EverandChoosing a Good Private School for Your Child: The Ultimate Guide for Parents and Guardians in ZambiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Konglish: The Ultimate Survival Guide for Teaching English in South KoreaVon EverandKonglish: The Ultimate Survival Guide for Teaching English in South KoreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual For Running A Library in A High School by Usha MukundaDokument10 SeitenManual For Running A Library in A High School by Usha MukundaPratham BooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christine Lopez Glms Program ReflectionDokument12 SeitenChristine Lopez Glms Program Reflectionapi-707702428Noch keine Bewertungen

- Time To Read Int 04 0Dokument70 SeitenTime To Read Int 04 0Lillis SarahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article ComprehensionDokument8 SeitenArticle Comprehensionroshdan69Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cultivating A Love of Reading in StudentsDokument21 SeitenCultivating A Love of Reading in StudentsRose Ann DingalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mary Tobin Initial Impressions EssayDokument3 SeitenMary Tobin Initial Impressions Essayapi-252326399Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ej 1063949Dokument8 SeitenEj 1063949api-520294983Noch keine Bewertungen

- Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Information Literacy But Were Afraid to GoogleVon EverandEverything You Always Wanted to Know About Information Literacy But Were Afraid to GoogleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lead with Literacy: A Pirate Leader's Guide to Developing a Culture of ReadersVon EverandLead with Literacy: A Pirate Leader's Guide to Developing a Culture of ReadersBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Traditional Library Versus New Technology Such As eDokument10 SeitenTraditional Library Versus New Technology Such As eAnonymous fjFtyLiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Information Literacy in Higher Education: Effective Teaching and Active LearningVon EverandTeaching Information Literacy in Higher Education: Effective Teaching and Active LearningBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Teaching Children to Read Effectively: Strategies for ParentsVon EverandTeaching Children to Read Effectively: Strategies for ParentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opening Doors to a Richer English Curriculum for Ages 10 to 13 (Opening Doors series)Von EverandOpening Doors to a Richer English Curriculum for Ages 10 to 13 (Opening Doors series)Noch keine Bewertungen

- For The Love of Reading Engaging Students in A Lifelong PursuitDokument6 SeitenFor The Love of Reading Engaging Students in A Lifelong PursuitPrinces Andrea CANLASNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Nanny’S Day—The Professional Way! the Social Studies Book: A Curriculum Book for the Professional Early Childhood NannyVon EverandA Nanny’S Day—The Professional Way! the Social Studies Book: A Curriculum Book for the Professional Early Childhood NannyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Questions About Independent ReadingDokument4 Seiten10 Questions About Independent ReadingSylvia IbarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maam SheddDokument2 SeitenMaam SheddNur-Sallah AbbasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Read for a Better World ™ Educator Guide Grades PreK-1Von EverandRead for a Better World ™ Educator Guide Grades PreK-1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Informal Learning and Field Trips: Engaging Students in Standards-Based Experiences across the K?5 CurriculumVon EverandInformal Learning and Field Trips: Engaging Students in Standards-Based Experiences across the K?5 CurriculumNoch keine Bewertungen

- StrategiesDokument2 SeitenStrategiesangelynardeno28Noch keine Bewertungen

- High Impact Reading Instruction and Intervention in the Primary Years: From Theory to PracticeVon EverandHigh Impact Reading Instruction and Intervention in the Primary Years: From Theory to PracticeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Fortuitous Teacher: A Guide to Successful One-Shot Library InstructionVon EverandThe Fortuitous Teacher: A Guide to Successful One-Shot Library InstructionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Read for a Better World ™ Educator Guide Grades 2-3Von EverandRead for a Better World ™ Educator Guide Grades 2-3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Construction Begins, But ITER's Costs SpiralDokument1 SeiteConstruction Begins, But ITER's Costs SpiralshilpaiprNoch keine Bewertungen

- Block 4 BLIS 03 Unit 12Dokument17 SeitenBlock 4 BLIS 03 Unit 12ravinderreddynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Block 4 BLIS 03 Unit 12Dokument17 SeitenBlock 4 BLIS 03 Unit 12ravinderreddynNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Tale of Two Libraries - The HinduDokument9 SeitenA Tale of Two Libraries - The HindushilpaiprNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hamiltonian Formulation For The Classical EM Radiation-Reaction Problem: Application To The Kinetic Theory For Relativistic Collisionless PlasmasDokument31 SeitenHamiltonian Formulation For The Classical EM Radiation-Reaction Problem: Application To The Kinetic Theory For Relativistic Collisionless PlasmasshilpaiprNoch keine Bewertungen

- NASA-CR-195454: Enhanced Analysis and Users Manual For Radial-Inflow Turbine Conceptual Design Code RTDDokument26 SeitenNASA-CR-195454: Enhanced Analysis and Users Manual For Radial-Inflow Turbine Conceptual Design Code RTDshilpaiprNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zero DiallingDokument1 SeiteZero DiallingshilpaiprNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shared Reading Week of 0127Dokument10 SeitenShared Reading Week of 0127api-241777721Noch keine Bewertungen

- Zahavi Dan Husserl S Phenomenology PDFDokument188 SeitenZahavi Dan Husserl S Phenomenology PDFManuel Pepo Salfate50% (2)

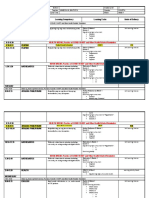

- Weekly Home Learning Plan Day and Time Learning Area Learning Competency Learning Tasks Mode of Delivery Monday 8:00-9:15 FilipinoDokument5 SeitenWeekly Home Learning Plan Day and Time Learning Area Learning Competency Learning Tasks Mode of Delivery Monday 8:00-9:15 FilipinoVanessa BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLP Contemporary Arts COTDokument8 SeitenDLP Contemporary Arts COTriza macasinag86% (7)

- A Study On The Relationship Between Burnout and Occupational Stress Among Nurses in Ormoc CityDokument18 SeitenA Study On The Relationship Between Burnout and Occupational Stress Among Nurses in Ormoc CityNyCh 18Noch keine Bewertungen

- Intercultural CommunicationDokument4 SeitenIntercultural CommunicationlilychengmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLP Mapeh G7Dokument2 SeitenDLP Mapeh G7HannahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Five Educational PhilosophiesDokument2 SeitenSummary of Five Educational PhilosophiesKheona MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Das 2 Self AdministerednDokument5 SeitenWho Das 2 Self AdministerednJarmy BjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report Journal Review - Group 15Dokument12 SeitenReport Journal Review - Group 15e22a0428Noch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Directions Fy 2017-2022Dokument20 SeitenStrategic Directions Fy 2017-2022GJ BadenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing Leadership & Management (6HR510) : Derby - Ac.uDokument26 SeitenDeveloping Leadership & Management (6HR510) : Derby - Ac.uaakanksha_rinniNoch keine Bewertungen

- გაკვეთილის ანალიზიDokument2 Seitenგაკვეთილის ანალიზიliliNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA Coaching and Institutes IndiaDokument2 SeitenMBA Coaching and Institutes IndiamakemycareerNoch keine Bewertungen

- English 9 Efdt 3Dokument6 SeitenEnglish 9 Efdt 3John Mark PascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student LogbookDokument9 SeitenStudent LogbookMohd Yusuf100% (1)

- PTC First Year SyllabusDokument3 SeitenPTC First Year Syllabuscm_chemical81100% (2)

- Teaching ESL Learners - Assignment 1 Syllabus Design Tôn N Hoàng Anh Ho Chi Minh City Open UniversityDokument18 SeitenTeaching ESL Learners - Assignment 1 Syllabus Design Tôn N Hoàng Anh Ho Chi Minh City Open UniversityAnh TonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Influential Factors Among Senior High School Students' Career Preferences: A Case of Private SchoolDokument16 SeitenInfluential Factors Among Senior High School Students' Career Preferences: A Case of Private SchoolLOPEZ, Maria Alessandra B.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Blooms Taxonomy of Educational Objectives-RevisedDokument12 SeitenBlooms Taxonomy of Educational Objectives-RevisedMary Ann FutalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Theories of Public Policy Decision MakingDokument30 SeitenIntroduction To Theories of Public Policy Decision Makingpaakwesi1015Noch keine Bewertungen

- Athanasia Gounari CVDokument2 SeitenAthanasia Gounari CVMiss NancyNoch keine Bewertungen

- PathologyDokument5 SeitenPathologyjohn aveaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand Engagement SynopsisDokument15 SeitenBrand Engagement SynopsisKhushboo ManchandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aguilera Sánchez, Mavy Lena - BS4S14 A2Dokument6 SeitenAguilera Sánchez, Mavy Lena - BS4S14 A2Mavy Aguilera SánchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manal KhalilDokument2 SeitenManal KhalilBagi MojsovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CU 7. Developing Teaching PlanDokument36 SeitenCU 7. Developing Teaching PlanJeramie MacabutasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arief PDFDokument8 SeitenArief PDFElya AmaliiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vdoc - Pub - Teaching Secondary MathematicsDokument401 SeitenVdoc - Pub - Teaching Secondary MathematicsMohammed FazilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cohesive Explicitness and Explicitation in An English-German Translation CorpusDokument25 SeitenCohesive Explicitness and Explicitation in An English-German Translation CorpusWaleed OthmanNoch keine Bewertungen