Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Invesigating The Source of Idiom Transparency Intuitions

Hochgeladen von

Zahraa LotfyOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Invesigating The Source of Idiom Transparency Intuitions

Hochgeladen von

Zahraa LotfyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by: [American University in Cairo] On: 19 March 2012, At: 14:22 Publisher: Psychology

Press Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Metaphor and Symbol

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hmet20

Investigating the Source of Idiom Transparency Intuitions

Sophia Skoufaki

a a

National Taiwan University

Available online: 16 Jan 2009

To cite this article: Sophia Skoufaki (2008): Investigating the Source of Idiom Transparency Intuitions, Metaphor and Symbol, 24:1, 20-41 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926480802568448

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Metaphor and Symbol, 24: 2041, 2009 Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1092-6488 print / 1532-7868 online DOI: 10.1080/10926480802568448

Metaphor 1532-7868 1092-6488 HMET and Symbol Vol. 24, No. 1, November 2008: pp. 144 Symbol,

Investigating the Source of Idiom Transparency Intuitions

Sophia Skoufaki

National Taiwan University

SKOUFAKI Investigating the Source of Idiom Transparency Intuitions

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

Two accounts have been given for the formation of idiom transparency intuitions. For most researchers, an idiom is transparent to the degree that a link can be found between its form and meaning. Cognitive linguists agree with the aforementioned view, but claim there is an additional source of transparency intuitions. They claim that transparency is partly the degree to which features inherent in an idiom (e.g., conceptual metaphors that are considered to underlie it) are seen as contributing to the idioms meaning even before someone learns it. This article reports the results of an experiment which examines whether the cognitive linguistic claim about a hybrid source of idiom transparency intuitions is correct. Advanced second language learners of English guessed at the meaning of unknown idioms presented in or out of context. The results are congruent only with the hybrid view of idiom transparency. They indicate that idiom-inherent features contribute to the formation of transparency intuitions. In particular, although the idioms were unknown to participants, (1) high-transparency idioms received a significantly smaller number of interpretation types (not tokens) than low-transparency idioms in both context conditions, and (2) a significantly higher-than-chance number of correct idiom interpretations was given to high- rather than low- transparency idioms. However, the definition of transparency as the extent to which the meaning of an idiom can be guessed correctly, which is supported by some cognitive linguists, is not supported here: (a) the level of association between transparency and correct interpretations was low, and (b) when context was provided, the difference in the number of correct definitions between high- and low-transparency idioms was not significant.

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS According to traditional linguistic research, idioms are expressions whose meanings cannot be computed compositionally (e.g., Fraser, 1970: 22; Strassler, 1982: 15). However, the innovatory work of Nunberg and his colleagues (e.g., Nunberg, 1977; Nunberg, Sag, & Wasow, 1994) has shown that idioms do not form a homogeneous group, but vary in terms of various dimensions, such as informality, figuration, and transparency. Idiom researchers agree that idiom transparency is the degree to which native speakers consider an idiomatic expression as related to its figurative meaning, but there is controversy over the mental processes that lead to idiom transparency intuitions. This paper aims to shed some light on the sources of idiom transparency intuitions. For most researchers, intuitions of transparency stem from the explanation a language user thinks of to motivate the form of an idiom after learning its idiomatic meaning. For example, for

Address correspondence to Sophia Skoufaki, Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Taiwan University, 1 Roosevelt Road, Sec. 4, Taipei 10617, Taiwan. E-mail: sophiaskoufaki@ntu.edu.tw

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

21

Nunberg, Sag, and Wasow (1994: 496), an idiom is transparent to the extent that native speakers can recover the rationale for the figuration it involves. Similarly, Cacciari, Glucksberg, and their colleagues (Cacciari & Levorato, 1998; Cacciari & Glucksberg, 1991; Glucksberg, 1993) have posited that an idiom is analysabletheir term for transparentto the extent that someone can perceive a link between the meaning of the words forming the idiom and its overall figurative interpretation. By contrast, cognitive linguists (e.g., Geeraerts, 1995) and psychologists who use this framework (e.g., Gibbs et al., 1997) support a hybrid view of idiom transparency. They agree that intuitions of transparency stem from ones search for a link between an idioms meaning and form after one has learned that meaning, but claim that one partly forms transparency intuitions by resorting to knowledge structures considered inherent in an idiom, such as conceptual metaphors, metonymies, and encyclopedic knowledge. The belief of some cognitive linguists in the central role of the aforementioned conceptual structures in transparency intuitions formation has led to the conceptualisation of transparency as the degree to which it is possible for one to guess at the meaning of an idiom based on an examination of its form (e.g., see the definition of transparency in Boers & Demecheleer, 2001: 255). A few experimental studies have examined which of the two aforementioned positions about the determinants of idiom transparency intuitions is correct. Results in Keysar and Bly (1995) support the claim that idiom transparency intuitions are formed only after one has learned an idioms meaning. Keysar and Blys two experiments began with the implicit instruction of true or false meanings of idioms shown to be unknown to participants according to a norming study. This norming study consisted of a familiarity rating for each of 20 idioms, and the selection of one of two definitions for each idiom, one being the original definition and the other being its opposite. The researchers selected 15 idioms that had a mean score of 2 on a 7-point scale ascending in familiarity and that were, on average, equally biased towards the original and opposite meanings. In their first experiment, participants learned either the original or the opposite meaning of an idiom by reading a story which biased them towards one of the two meanings. For example, the text for the idiom the goose hangs high, read that the two protagonists-farmers would have a good harvest and finished with one of them agreeing with the others comment that this year looks good by saying, Aye, John, the goose hangs high. This text biased the reader towards the original meaning of the idiom. The other text biased the reader for the opposite interpretation, by having the narrator say that the year had been disastrous for them. Participants then chose which of the three meanings supplied to them they considered correct. These meanings were the two aforementioned ones and an unpredictable one serving as control. After finishing this task for all 15 idioms, participants proceeded to the second phase of the experiment. They were asked to indicate which of the three meanings they expected a person who did not know the meaning of the idiom would think of if (s)he overheard it, and to rate their confidence about their choices. The researchers hypothesis was that participants (a) would expect the overhearer to think of the meaning they had learned, (b) would be fairly confident in their choices, and (c) would be more confident when they attributed the meaning they had learned to the overhearer than when they attributed the opposite meaning to him or her. These results were found in most cases, thus providing evidence that there is nothing inherent in an idiom that determines its interpretation; otherwise, the original interpretation would be considered more likely to be thought of by a nave overhearer. Their second experiment was a variation of the first. Its results indicated that the more an idiom had been practiced, the less sense the non-learned meaning made to the participants; by contrast, the learned meanings ratings were unaffected by use.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

22

SKOUFAKI

Keysar and Bly (1995) concluded that features of idioms do not determine intuitions of transparency. Their speculation about how other sources of information about an idioms meaning can interact with the meaning that has been learned is that once one has learned the meaning of an idiom, (s)he looks for elements in the idiom which allow such a meaning. According to Keysar and Bly, this is the point where ones conceptual metaphoric, metonymic, and encyclopedic knowledge may influence ones representation of an idioms transparency. However, there is reason to think that their experimental results are due to the methodology used. First, according to a transparency rating study (Skoufaki, 2006: 105107) which will be summarized in the Materials section of this paper, 11 out of the 14 idioms in the study are of low transparency. This fact could indicate that their claim holds only for low-transparency idioms. Second, the presentation of idioms in highly biasing contexts is not ecologically valid and may have led subjects to base their answers more on contextual information than on idiom-internal features. Third, asking subjects to circle one of three definitions for each idiom instead of asking them to offer their own interpretations in the idiom-learning phase may have also preempted their use of guessing strategies based on idiom-inherent features. Finally, in both experiments participants who had been taught the opposite meaning may have responded that they considered it more sensible than the original meaning not because they indeed considered it more sensible. It is common knowledge that idiom forms are arbitrarily linked to their meanings, so their judgment may have been biased by the meaning they had been taught. These criticisms seem all the more warranted given the results of the norming study that preceded the experiments. As mentioned above, one of the tasks in this study was the selection of one of two definitions for each idiom, one being the original definition and the other its opposite. The mean correct choices were 51%, but the original meaning was chosen out of context with a significantly higher than chance rate for some idioms, since correct choices ranged from 15% to 82% (Keysar & Bly, 1995: 93). Based on this fact and on the finding that in this norming study familiarity did not significantly correlate with accuracy, one could suppose that not only the biasing contexts, but also differences among idioms in terms of the ease of guessing an idioms meaning correctlywhich was not controlled forcaused the pattern of replies to the multiple choice definition task in the experiments. Bortfeld (1998, 2002) conducted a set of studies which support cognitive linguistic claims regarding the source of idiom transparency intuitions. The hypothesis was that non-native (L2) speakers of English would express the same kind of knowledge when asked to describe the mental images evoked by idioms unknown to them and presented out of context (e.g., go off your rocker) as the native speakers, who would be familiar with the idioms.1 Her first and second experiment had a methodological confound. Since participants were presented with the meanings of idioms and then asked to talk about their mental images, their reported images may have indicated their knowledge of the idioms meanings, rather than the conceptual knowledge they would have used in order to guess at them. To avoid this confound and other methodological problems of these experiments, Bortfeld conducted another experiment where L2 learners wrote about the image evoked by each idiom and answered questions about it both before and after they had been told the definition of each idiom. The results showed that L2 learners used their

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

1 These questions, as well as the design of her experiments, were modelled after Gibbs and OBriens (1990) similar studies.

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

23

conceptual metaphoric knowledge when thinking of the images for the idioms both before and after the definition. After the imaging task, participants images and answers to the relevant questions showed that 49% of the time they could understand the meaning of the idiom correctly, even when they had not been told an idioms definition. Bortfeld (2002: 292293) considers this finding as evidence that transparency is a feature of the idiom and does not have to result from an attempt to link the idioms form with its meaning. Bortfeld (2003) further investigated the nature of idiom transparency. One of her claims is that an idioms decomposability can affect how well and fast someone can guess the meaning of an unknown idiom. This claim is related to our discussion because (1) decomposability is an idiom characteristic that is considered by some researchers as one of the causes of idiom transparency intuitions (e.g., Boer & Demecheleer, 2001; Gibbs & Nayak, 1989), and (2) as we have mentioned above, idiom transparency has been understood by some cognitive linguists as the extent to which an idioms meaning is guessable (e.g. Boers & Demecheleer, 2001). Taken together, these cognitive linguistic claims lead to the claim that if idiom-inherent features contribute to transparency intuitions, perhaps an idioms level of compositionality may affect how guessable its meaning is. Decomposability is a concept initially posited by Nunberg (1977). Idioms are divided into decomposable (a link between an idioms meaning and its form can be found by native speakers) and non-decomposable (where no such link can be found). Decomposable idioms are divided into normally and abnormally decomposable. In normally decomposable idioms, a link can be found between certain literal meanings of the idioms words and parts of the idiomatic meaning (e.g., in pop the question, one can easily infer that pop refers to asking the question and the question is the proposal, because knowledge of the idioms meaning guides one toward the relevant literal meanings of the words pop and question). In abnormally decomposable idioms, a metaphor, rather than literal word meanings, linking the literal and idiomatic meanings determines the meaning people assign to the words in the idiom (e.g., ring a bell is linked to its meaning through a conventional metaphor whereby becoming aware of something is associated to being alarmed by a sound). The hypothesis in Bortfeld (2003) that is of interest to us is that native English speakers will be able to choose the correct definitions of idioms translated into English from an unknown language more often when they are normally decomposable rather than abnormally decomposable or non-decomposable. The rationale is that the former idioms are linked to conceptual structures which are shared cross-linguistically. In Bortfelds first experiment, idioms previously rated in terms of their decomposability by two native speakers of English (e.g., to go into pieces) were individually presented out of context on a computer screen to native speakers of English. Participants were asked to state, after seeing each idiom, whether its meaning was related to the concept of Revelation, Insanity, Control, Anger, or Secretiveness by pressing one of the buttons corresponding to each of these concepts. Their performance with native-language idioms was compared with the performance of native English speakers with translations of Latvian idioms in Experiment 2, and Mandarin idioms in Experiment 3. The result relevant to our discussion was that both these experiments showed the same descending pattern in terms of correct meaning categorizations depending on idiom decomposability as Experiment 1: the normally decomposable idioms were categorized correctly most often, followed by the abnormally decomposable, and then the non-decomposable idioms. This pattern was seen as indicating that the surface forms of many idioms are, in fact, analyzable for their underlying figurative meaning. (Bortfeld, 2003: 226). However, as Bortfeld

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

24

SKOUFAKI

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

(2003: 227) admits, her experiments did not give any distractors in the multiple choice categorization questions. Therefore, one cannot say that in Experiments 2 and 3 participants could guess at the meaning of normally decomposable idioms more often than the rest, but just that given the very restricted meaning choice they were given, they could make sense more easily of the form of the normally decomposable idioms. If the same result was found with a wider variety of choices, or if the learners were asked to give their own definitions, these experiments would constitute compelling evidence that the meaning of normally decomposable idioms can be guessed at correctly more often than that of abnormally decomposable and non-decomposable idioms. The experiment reported here aims to give a clearer answer to the controversy surrounding the sources of idiom transparency intuitions. Since there is no controversy regarding the claim that idiom transparency intuitions are formed through an attempt to find some motivation for an idioms form after the idioms meaning has been learned, this experiment focuses on examining whether knowledge structures, such as conceptual metaphors, encyclopedic knowledge, and semantic knowledge, about words in idioms contribute to ones intuitions of idiom transparency before one has learned the meaning of an idiom. In this experiment, participants are presented with unknown idioms in or out of context and are asked to guess at the meaning of these idioms and supply their idiom interpretations. The main hypothesis is that if participants use idiominherent features to guess at the meanings of idioms, a smaller number of types (not tokens) of interpretations will be given for high- rather than low-transparency idioms. A secondary hypothesis is that this difference in the number of interpretation types will be lower in the context than in the no-context condition because participants will rely more on contextual clues when provided.

THE STUDY The experiment reported here tests whether the hybrid view of idiom transparency, that is, the claim that both knowledge of an idioms meaning and knowledge derived from idiom-inherent features contribute to the formation of transparency intuitions, is correct. It uses an idiom-meaning guessing task to examine which of the following predictions will be supported. On one hand, the hybrid view of transparency predicts that the number of different types (not tokens) of idiom interpretations will be significantly smaller for high- as compared to low-transparency idioms. Such evidence would indicate that idiom-inherent features can have an effect on idiom transparency intuitions. On the other hand, the usual view of idiom transparency, that is, that idiom transparency intuitions are formed only after one has learned an idioms meaning, predicts that there will be no significant difference between the number of interpretation types given to highversus low-transparency idioms. Such data would indicate that people do not form any idiom transparency intuitions before learning the meaning of an idiom. In the introductory section of this paper, it has been claimed that in Keysar and Bly (1995), presenting idioms in highly biasing contexts may have led subjects to base their answers more on contextual information than on idiom-internal features. The experiment reported here tested this claim by presenting half of the participants with the idioms out of biasing contexts, and the other half in biasing contexts and comparing the number of idiom interpretation types between the out-of-context and in-context conditions. The hypothesis that supports the hybrid view of idiom transparency is that fewer interpretation types will be given to idioms when they are presented within context than when they are presented outside context.

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

25

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

In the study reported here, Greek advanced-level learners of English wrote their guesses of the meanings of idioms unknown to them.2 Participants were advanced learners rather than native speakers of English because this experiment was conducted with language learning and teaching implications in mind. Guessing at idiom meanings has been proposed by applied linguists of both cognitive linguistic (Boers & Demecheleer, 2001; Kvecses & Szab, 1996) and non-cognitive linguistic background (Irujo, 1984, 1993; Lennon, 1998) as an effective way of promoting the memorization of L2 idioms form and meaning. This idiom instruction proposal is relevant to the issue of the source of idiom transparency intuitions because most of the aforementioned researchers (Boers and Demecheleer, 2001; Irujo, 1993; Kvecses and Szab, 1996) claim that the meaning of highly transparent idioms can be guessed at correctly. If the experimental participants offer fewer idiom interpretation types for high- rather than low-transparency idioms, this finding can be seen as evidence that L2 learners are likely to be able to learn the meaning of high-transparency idioms by guessing at their meaning. This claim will be supported more directly if significantly more correct idiom interpretations are provided by participants for high-transparency rather than low-transparency idioms. Therefore, the third hypothesis of this study is that more correct idiom interpretations will be given for high- rather than low-transparency idioms. Method Participants. Sixty-four Greek advanced-level second-language learners of English (mean age = 20.6 years, SD = 4.1 years) participated in this study. They were all native speakers of Greek and students of various disciplines at the University of Athens, Greece. They all attended English lessons preparing them for the CPE (Cambridge Proficiency in English) examination at the Language Center of the university. They were paid for their participation. Materials. Twenty-four idioms with the structure Verb+Noun Phrase (Prepositional Phrase) were the materials in this study. In one condition, they appeared out of context, and in the other inside context. They were selected from the study mentioned earlier as showing that the majority of the idioms in Keysar and Bly (1995) were of low transparency. The criteria of selection were that (a) half of the idioms were of low transparency and half were of high transparency, and (b) they would be unknown or of very low familiarity to native speakers of English (the rationale was that if native English speakers were not familiar with certain idioms, advanced learners of English would probably not know them either). As mentioned above, this norming study included the idioms used in Keysar and Bly (1995). It also included 46 of the 136 Verb+Noun Phrase (Prepositional Phrase) idioms rated in a previous norming study I conducted using the same method. The latter were used as fillers so that the participants attention would be distracted from the fact that the idioms I was interested in were

This study also aimed to examine the kinds of knowledge structures that participants used to guess at the meanings of these unknown idioms (e.g., word meanings, conceptual metaphors, idioms with the same or semantically related words). In order to reach this goal, the study used a method similar to that in Cacciari (1993). Immediately after supplying an interpretation for an idiom, participants had to describe the train of thought that led them to it. However, the data derived from these immediate retrospective verbal protocols is not analysed here because this issue is not within the scope of this article. For the details of the procedure, results, and conclusions relating to this issue, see Skoufaki (2006: 112113, 120129, 131132), respectively.

2

26

SKOUFAKI

low in familiarity. To have an equal number of idioms from each level of familiarity (low, medium, high), I included only six fillers that had been rated as low familiarity, and two groups of 20 fillers, one of medium and the other of high familiarity idioms. I also wanted to balance the idioms in terms of transparency level (low, medium, high) and expected that most of the Keysar and Bly idioms would be low in transparency. Therefore, half of the low familiarity idioms were chosen to be of medium and half of high transparency; in each of the other two familiarity groups, three idioms were of low transparency, eight idioms were of medium transparency, and nine of high transparency. This norming study, as well as the one mentioned above, consisted of a transparency and a familiarity rating task. Twenty British students at the University of Cambridge were asked to rate 60 Verb+Noun Phrase (Prepositional Phrase) idioms on a 7-point scale in terms of familiarity and transparency. The idioms appeared in sentences with personal pronouns filling the subject, object, and any other related position (e.g., They praised him to the skies.). Below each idiom was its definition adapted from the Collins COBUILD Dictionary of Idioms (Sinclair, 1995). In both rating tasks, participants were instructed to feel free to use the entire scale in making their ratings. In the familiarity rating task, idioms appeared on paper in a list, and next to each was a 7-point rating scale, where 1 stood for never heard it and 7 for hear it often. Participants were instructed not to try to compare the relative familiarity of the variants but just give the familiarity rating of the form they were more familiar with irrespective of whether it is in the booklet or not, although an attempt was made to present all the variants of an idiom (e.g., The idiom to reach the end of the road/line was presented as It has reached the end of the road/line.). This task was followed by a transparency rating one. A non-technical definition of transparency was given with examples of high- and low-transparency idioms. Participants were asked to rate, on a 7-point scale, the idioms they had seen in the previous task in terms of how much they thought the meanings of words or phrases in each idiom and the idioms meaning were related. In this scale, 1 meant totally unrelated and 7 meant very related to the idioms meaning. As some participants might take this task as an investigation of their knowledge of how an idioms meaning came about, the instructions also read that participants should not use any knowledge of the idiomatic meanings origin but state the degree to which the meaning of the words themselves is related to that of the idiom. The ratings for each idiom were averaged. Out of the 14 idioms in Keysar and Bly (1995), 1 was rated as highly transparent, 11 as low transparency, and 2 as medium transparency. From these idioms, I included in the materials the high-transparency one and 7 of the low-transparency ones. Two of the other low-transparency ones (row cross-handed and get the deadwood on someone) were excluded because the learners might have unknown words in them, according to the judgment of three Greek teachers of English. The third low-transparency idiom, eat someones salt, was not included because I expected that there would be an unusually high rate of correct idiom-meaning guesses for this idiom due to positive transfer from a Greek idiom with similar form and meaning. The last low-transparency idiom, come the uncle over someone, was not included because its transparency ratings distribution was not normal. I intended to have an equal number of low-, medium-, and high-transparency idioms in the experiment. However, it was impossible to find enough items in each of these categories, so idioms were recategorized into two transparency categories. Those that had a mean of 3.5 or above were named high-transparency and the rest were low-transparency that idioms.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

27

The materials of the main study consisted of 12 low-transparency and 12 high-transparency idioms. Because there were 24 idioms in total, and in the pilot study of this experiment participants needed one hour to guess at the meaning of 10 idioms, half of the idioms are presented out of context to a group of 16 people and the other half to another group, and the same applies to the within-context condition. So, there are 4 groups of people, 16 in each group. Four filler texts containing one high-transparency idiom each were included in the materials to make sure that the data from the subjects in the different conditions were comparable. These texts appeared in both the context and no-context conditions. They are presented in Appendix A. In the data analysis, I compared the proportions of each kind of definition (literal, correct, plausible, no answer/nonsense) given for these idioms among the conditions to find out whether the participants differed significantly in terms of their judgment across groups. As mentioned above, context is a factor in the experiment in order to compare the role that idiom-inherent features play when contextual clues are provided and when they are not. In one condition, idioms appeared with only their subject, object, or any other related position filled in with pronouns (e.g., She set her cap at him.), whereas in the other, half the idioms appeared in the last line of short texts. Keysar and Bly supplied the texts they used to bias participants towards the original and opposite interpretation for all the idioms used in this experiment except set ones cap at someone. Therefore, I constructed my own text for this idiom. The text for play the bird with the long neck seemed to me to have many words which might be unknown to the participants, so I substituted it with one which I constructed. To render all texts equally biasing, that is, offering a similar amount of assistance to the reader to reach the correct idiom interpretation, the clues in the texts were standardized. According to research on the informativeness of textual clues about unknown words in a text (e.g., Ames, 1966; Carnine, Kameenui, & Coyle, 1984), both the texts in Keysar and Bly (1995) and my texts for the rest of the idioms are more or less equally informative; most of them let the reader infer the meaning of the idiom instead of giving him or her more explicit information about it (e.g., a synonym or an antonym, which have been shown to be more helpful than expressions which promote inference). Experiments which manipulate the distance between the clues and the unknown word in a text (e.g., Carnine, Kameenui, & Coyle, 1984) show that guesses are less successful when the clue is distant. Therefore, the distance between the clue and the idiom was standardized in the following way. Three Greek teachers of English located the clues for the idioms interpretations in these texts so that the standardization of the clues would not be based on my judgment alone. Whenever their judgments differed, they were asked to cooperate in order to reach a common decision. They also checked whether the texts contained any words that could be unknown to advanced-level students. Then I amended the texts so that each would have only one clue and there would be around 10 words between the clue and the idiom. Therefore, each text had one clue and the distance between the idiom and the clue ranged from 6 to 14 words. The number of sentences in each text was also kept similar, ranging from five to eight lines. Appendix B presents the idioms as they appeared in the no-context and context conditions. Procedure. As mentioned above, because there were 24 idioms in total and in the pilot study of this experiment participants needed one hour to guess at the meaning of 10 idioms, half of the idioms out of context were presented to a group of 16 people and the other half to another group and the same happened in the within-context condition. In each group, half of the experimental items were low transparency and the other half were high transparency.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

28

SKOUFAKI

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

Each participant was presented with a booklet. Each page in the booklet contained two questions about an idiom. The first was a yes/no question on whether they already knew the meaning of this idiom. If a participant gave a negative answer, he or she should go on to the second question and write his or her interpretation of the idiom.3 Participants were also asked to circle any word in the idiom or the text in which it occurred if they thought that their lack of knowledge for this word prevented them from understanding the idioms meaning. They were also told that they could also ask me, since I conducted the experiment, for Greek translations of these words, if they wanted, so that their idiom interpretations would not be based on unknown vocabulary 4. As mentioned in the Materials section of this paper, when idioms were presented out of context, personal pronouns filled the subject, object, and any other related position. In the other condition, idioms were presented in italics in the last sentences of small texts containing clues about the idioms meaning. The materials were presented in a different order to each participant and participants were assigned randomly to conditions. Participants were tested in groups. The experiment lasted one hour.

RESULTS Two judges other than the aforementioned Greek teachers of English, both adult Greeks fluent in English, categorized the definitions participants gave for the idioms among the following categories: literal, correct, plausible, and no answer/nonsense. To do this task, they were provided with the instructions shown in Appendix C together with a list of correct idiom definitions. The judges also categorized the participants reports of thoughts leading to the interpretations in categories formed by themselves. However, this analysis does not form part of the focus of this paper, so these results will not be reported here. I excluded from the analysis responses where an idiom had not been interpreted by a participant (6% of the total number of answers), cases where the idiom had been interpreted literally (2% of the total number of answers), cases where the participant stated that (s)he already knew the idiom and indeed offered a correct interpretation (3% of the total number of answers), and cases where a participant had circled a word to signify that it was unknown to him/her and which either belonged to the idiom or to the parts of the text that had been identified by the EFL teachers during materials construction as part of the idiom-meaning clues (4% of the total number of answers).

3 As mentioned in footnote 2, participants were then asked to describe the train of thought that led to this interpretation, but the relevant results and conclusions will not be reported here. 4 The translations I provided them with were those for the literal word meaning and whenever a word had an array of literal meanings, I gave them the one which seemed to me to be the most central. For example, board (which is in the idiom go by the board) has many literal meanings. According to the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (Fox et al., 2004), which cites the meanings in order of frequency, the first meaning is a flat wide piece of wood, plastic, etc. that you can use to show information, the second is a flat piece of wood, plastic, card, etc. that you use for a particular purpose such as cutting things on, or for playing indoor games, the third is a group of people in a company or other organisation who make the rules and important decisions, the fourth is used in the name of some organisations, and the fifth (after which, the dictionary cited idiomatic expressions including the word board) is a long thin flat piece of wood used for making floors, walls, fences, etc. I told the participants that this word can mean many things and gave them the meaning piece of wood.

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

29

After collecting the responses of the judges, I found the discrepancies in their categorizations of the participants interpretations in the literal, correct, plausible, and no answer/nonsense categories and asked them to resolve these differences. Their agreement before the resolution of their differences was assessed via Kappa tests, one for each of the four filler idioms common in all conditions. The agreement for only two of the fillers, fight ones corner (92%) and raise the roof (76%), exceeds the 70% minimum acceptable agreement level (Cramer, 1994). However, the low agreement level for the other two fillers, be in bad smell with someone and crack the whip, is not due to considerable differences between the two judges categorizations of definitions. A close inspection of the contingency tables for these two fillers5 shows that the majority of the discrepancies between the judges for the fillers were cases where judge A considered a definition plausible whereas judge B considered it correct. It seems, therefore, that the difference between the judges in these cases were only due to judge A being more strict on whether a definition is correct than judge B. Given that in the items where agreement was low the inter-judge differences were just a matter of whether they considered a definition correct or just plausible, inter-judge agreement was considered satisfactory. Since filler idioms were included in the materials of all groups, a chi-square test was conducted for each filler idiom to examine whether the four participant groups were comparable. The dependent variable was the literal, correct, plausible, no answer/nonsense response. Because the literal answers were very few, I compiled them with the no answer/nonsense answers. The chi-square test was not significant (Pearsons chi-square = 5.918, p(two-sided) > 0.05), so participant groups did not differ significantly in terms of the kinds of definitions produced. The main hypothesis of this study was that if idiom-inherent features influence the interpretation of unknown idioms, the number of different types (not tokens) of idiom interpretations would be significantly smaller for high- as compared to low-transparency idioms. Therefore, the mean number of interpretation types between high- and low-transparency idioms had to be compared to test this hypothesis. To determine the number of interpretation types given to each idiom, I categorized the interpretations for each idiom into groups expressing what I considered to be more or less the same meaning. Another Greek fluent speaker of English was asked to categorize the definitions into meaning groups as well. The instructions for this task are presented in Appendix D. The number of interpretations to categorize was very large (768) and the interpretation categories were not determined a priori but on the basis of the participants interpretations. Therefore, it would be very difficult to reach a common taxonomy through discussion of the differences between my and the other judges categorizations. Irrespective of that, in most cases, our categorizations differed only in terms of granularity, so it did not make sense to prefer one against the other by creating a final taxonomy. For example, one of the categories that the other judge created for the definitions for be heading for a fall corresponded to two of mine (To be on the way to fail/be destroyed possibly due to your own mistakes and despite your efforts versus to do something which may destroy you and to be heading for a disaster). The fact that the same pattern of statistical results appeared for both taxonomies can be seen as proof that my taxonomy was not biased by my being the researcher. Due to space limitations, I will present in detail the analysis of the results of only my, not the other judges, categorization of the definitions.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

These tables appear in Skoufaki (2006: 116).

30

SKOUFAKI

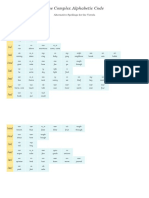

TABLE 1 Mean number of Definition Types Depending on Transparency and Context Conditions Transparency Low Out of context Within context High Out of context Within context Mean

7.73 5.02 4.93 2.96

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

The descriptive statistics in Table 1 indicate that low-transparency idioms received more definition types than high-transparency idioms and both kinds of idioms received more definition types when presented out of context than within context. Standard deviations are not mentioned because the distribution of the number of definition types was not normal (Shapiro-Wilk test = 0.94, p < 0.05). According to a Box-Cox normality plot, data was transformed via the square root transformation. Then a complex ANOVA for independent samples was run on this data. Transparency (high versus low) and context (context versus no context) were the independent variables and number of definition types was the dependent variable. There was a main effect for both transparency and context (F(1,63) = 3.54, p < 0.005 and F(1,63) = 3.24, p < 0.001, respectively). Their interaction was not significant (F(1,44) = 0.005, p > 0.05). The main effect for transparency and the lack of an interaction between the independent variables jointly indicate that transparency affected the number of interpretation types participants thought of in its own right, that is, not only when idioms appeared out of context. The main effect for context supports the view that in Keysar and Bly (1995), the presentation of idioms in highly biasing contexts may have led subjects to base their answers more on contextual information than on idiom-internal features. The smaller number of interpretation types given in both context conditions for high- rather than low-transparency idioms constitutes evidence that transparency stems not only from the analysis of the form-meaning links when one knows an idioms meaning, but also from the derivation of meaning from idiom-inherent features when one does not know it. It seemed reasonable, therefore, to test the cognitive linguistic claim that the meanings of highly transparent idioms are likely to be guessed at correctly more frequently than those of low-transparency idioms. For this test, the plausible and no answer/nonsense definitions were collapsed in order to compare the number of correct and false definitions irrespective of false-definition type. A chisquare test was conducted to examine whether the actual breakdown of correct and incorrect interpretations between the high- and low-transparency idioms differs significantly from the one which would be expected if the number of correct interpretations was unrelated to transparency. The independent variable was transparency (high versus low) and the dependent variable was interpretation success (correct versus incorrect interpretations). According to the contingency table, the majority of correct interpretations (71%) were given to the high-transparency idioms and the majority of incorrect interpretations (61%) were given to the low-transparency idioms. The value of the Pearson chi-square test was 4.463 and it was significant (p < 0.05). Taken together, the information in the contingency table and the chi-square tests significance indicate

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

31

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

that transparency affected the distribution of correct and incorrect interpretations given to idioms; a significantly higher than chance number of correct idiom interpretations were given to high-transparency idioms and a significantly higher than chance number of incorrect idiom interpretations were given to low-transparency idioms. To assess the power of the association between transparency level and number of correct and incorrect guesses, I tested for the significance of Cramers V. The value of this test was 0.305 (out of a possible maximum value of 1) and it was significant (p < 0.05). This low level of association between transparency and correct guesses indicates that some other factor determines the variety of definitions. A chi-square test where the dependent variable was interpretation success (correct versus incorrect interpretations) and the independent variable was transparency (high versus low) layered by context (context versus no context) was conducted to examine whether this factor is context. According to the contingency table, in both context conditions the majority of the correct interpretations were given to the high-transparency idioms, but this effect was stronger in the no-context condition (83%) than in the context condition (64%). By contrast, the provision of context did not affect the breakdown of the wrong definitions between high- and low-transparency idioms, since the same percentage of wrong definitions was given to each kind of idiom in the two context conditions (62% to low-transparency idioms). In the context condition, transparency did not have a significant effect on the number of correct and incorrect definitions given, since Pearsons chi-square = 0.686 and p(two-sided) > 0.05. The chi-square test was not valid in the no-context condition because of small expected frequencies (2 of the expected count cells were below 5). To summarize the results, on one hand the ANOVA test indicated that transparency affects the interpretations people come up with irrespective of context condition. On the other, the first chisquare test showed a low level of association between transparency and number of correct idiom interpretations and the second chi-square test showed no significant difference from that expected by chance in the distribution of correct and incorrect interpretations in the context condition. In view of these results, one can claim that transparency induced by idiom features affects idiom-meaning guesses both in and out of context. However, if transparency is defined as the extent to which the meaning of an idiom can be guessed correctly, the results show that when context is provided people rely more on contextual clues than on idiom-inherent features to form their transparency intuitions.

DISCUSSION The study presented in this paper provides empirical evidence in favor of the hybrid view of idiom transparency. On the one hand, although participants were not familiar with the input idioms, hightransparency idioms received significantly fewer types of interpretations than the low-transparency ones when presented both in and out of context. This finding indicates that intuitions of idiom transparency are based not only on mental processes which link an idioms form with its already known meaning, but also on mental processes that use idiom-inherent and contextual features to guess at the meaning of an idiom when one first encounters it. On the other hand, a low level of association was found between idiom transparency and correct idiom interpretations and in the context condition, the distribution of correct and incorrect idiom interpretations between high- and low-transparency idioms was not significantly different than that predicted by chance. These last two findings indicate that contextual clues were the main source of transparency intuitions.

32

SKOUFAKI

These results contrast with those in Keysar and Bly (1995). Because they found that the original meanings of idioms were not considered more sensible more often than the opposite meanings, they concluded that knowledge of an idioms meaning determines intuitions of transparency. The study reported here indicates that even when context is given, highly transparent idioms lead to a significantly smaller variety of definitions than low-transparency idioms. This finding contrasts with Keysar and Bly (1995) in that it indicates that idiom transparency intuitions are created not only when one knows an idioms meaning but also during ones initial encounter with an idiom. Moreover, this finding and the significant effect of transparency on and the number of correct idiom interpretations indicate that during ones first encounter with an idiom not only context but also idiom-inherent features play a role in creating transparency intuitions. I attribute the conflicting results to the fact that Keysar and Blys results seem to be, to a considerable extent, methodological artefacts. As shown by the results of my transparency rating study, native speakers rated most of their idioms as low in transparency. This fact combined with my finding that low-transparency idioms were given more definition types than the hightransparency ones indicates that their results may be due to their using mainly low-transparency idioms. Moreover, the use of low-transparency idioms in highly biasing contexts and forced definition choice may have preempted the partial reliance of participants on idiom-inherent features to form their interpretations. A methodological criticism that could be expressed about the study reported here is that the use of learners of a language instead of native speakers as experimental participants does not lead to native-like intuitions of transparency. For example, Keysar and Bly (1999: 1566) criticize Coulmass (1981:149) parallelism between the mental processes involved in the interpretation of an unknown L2 idiom and the mental processes involved in making sense of novel idioms in ones native tongue. Keysar and Bly say that the non-native speakers mental processes might not be native-like, because foreigners possess a different conceptual system. I think that this criticism does not apply to my experiment, given certain features of its design and participants. Instead of presenting the English idioms translated into Greek to the Greek learners, I presented them in English; hence, the learners had to use their knowledge of English vocabulary and syntax, rather than Greek. Moreover, participants were urged to circle any unknown words they had in an idiom and/or its preceding text, and when these words were crucial to the interpretation of the idiom their reply was excluded from the analysis. As mentioned in the Procedure section of this paper, participants could also ask me for Greek translations of unknown words, so the replies they gave could not be attributed to their ignorance of L2 vocabulary. Finally, the conceptual structure differences that may be due to cultural and linguistic factors cannot be substantial. Both English and Greek are Indo-European languages and both cultures are Western, so no big differences in the conceptual structure should be expected. Interestingly, the studys findings support my view that the conceptual structures that Greek L2 learners use when guessing at idiom meanings are similar to those that native English speakers would use to form transparency intuitions. Since the kinds of interpretations the L2 learners gave were fewer for the high- rather than for the low-transparency idioms, it seems that the native speakers in the norming study and the L2 learners agreed in their perception of idiom transparency levels although only the native speakers were presented with the idiom definitions. This finding could be seen as pointing to the close similarity of the conceptual knowledge that the L2 Greek participants and the native speakers in the norming study used to guess at the idioms meanings and judge their transparency level, respectively.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

33

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

The experiment reported here has two limitations with respect to the generalizability of the findings. One limitation is caused by the exclusive use of Verb Phrase (VP) idioms. English idioms fall into many different syntactic types and in order to render my research manageable I chose to investigate how transparency intuitions are formed for VP idioms. The use of only one syntactic type of idiom in the experiments does not allow for the results to be generalized across all types of idiom structures (e.g., phrasal verbs, phrasal constructions such as Adjective+Noun, frozen similes). The second limitation is the relatively small number of participants, which may be the reason why the last chi-square test was not valid in the no-context condition. Therefore, this study should be seen as exploratory and should be replicated with larger numbers of participants and idioms of other syntactic types. Greek advanced learners of English were used as participants because this experiment was partly conducted to see whether the experimental findings are congruent with the claim that guessing at idiomatic meaning can promote the memorization of unknown L2 idioms. According to the results of this experiment, idiom-transparency intuitions are not only based on context but also on idiom-inherent features. This finding may not support, but is at least congruent with the claim that L2 learners can fruitfully use idiom-inherent features to guess at idiomatic meaning. Moreover, the cognitive linguistic claim that the meaning of high-transparency idioms is more likely to be guessed at correctly than that of low-transparency idioms is supported since, according to the results of the first chi-square test, high-transparency was associated with correct idiom interpretations. However, this association was not strong, and, at least when context was given, transparency did not have a significant effect on the number of correct definitions.6 This result seems to imply that unambiguous contextual or other clues are necessary for learners to reach the correct idiom interpretation, a conclusion also supported by studies on the role of meaning inference in L2 vocabulary learning in general (e.g., Hulstijn, 1992; Wesche & Paribakht, 1998) and that of idioms in particular (Skoufaki, 2006, 2008). To conclude, the results of this study offer support to the hybrid view of idiom transparency. First, they indicate that idiom transparency intuitions are created not only after one has learned an idioms meaning but also when one is guessing at its meaning. Second, they also indicate that idiom-inherent features play a role in the formation of idiom transparency intuitions irrespective of whether they appear in a biasing context or not. Finally, if one considers transparency as the extent to which the meaning of an idiom can be guessed correctly, results indicate that contextual clues play a more important role than idiom-inherent features in the formation of idiom transparency intuitions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This article is based on my doctoral dissertation. Therefore, I would like to thank my supervising committee, Richard Breheny, Gillian Brown, and John Williams, for their valuable feedback and advice. I was supported by the Isaac Newton Trust, the Cambridge European Trust, the Allen, Meek, and Read Fund, Clare Hall, and the Research Centre for English and Applied Linguistics at the University of Cambridge.

6 No conclusion can be drawn about the role of transparency in the no-context condition since the chi-square statistic was not valid for this condition.

34

SKOUFAKI

REFERENCES

Ames, W. S. (1966). The development of a classification scheme of contextual aids. Reading Research Quarterly, 2(1), 5782. Boers, F., & Demecheleer, M. (2001). Measuring the impact of cross-cultural differences on learners; comprehension of imageable idioms. ELT Journal, 55(3), 255262. Bortfeld, H. (1998). A cross-linguistic analysis of idiom comprehension by native and non-native speakers. Ph.D. dissertation. Stony Brook, NY: State University of New York. Bortfeld, H. (2002). What native and non-native speakers images for idioms tell us about figurative language. In Heredia, R., & Altarriba, J. (Eds.), Advances in Psychology: Bilingual Sentence Processing (pp. 275295). North Holland: Elsevier Press. Bortfeld, H. (2003). Comprehending idioms cross-linguistically. Experimental Psychology, 50(3), 217230. Cacciari, C. (1993). The place of idioms in a literal and metaphorical world. In Cacciari, C., & Tabossi, P. (Eds.), Idioms: Processing, Structure, and Interpretation (pp. 2756). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Cacciari, C., & Glucksberg, S. (1991). Understanding idiomatic expressions: the contribution of word meanings. In Simpson, G. B. (Ed.), Understanding Word and Sentence (pp. 217240). Amsterdam: Elsevier. Cacciari, C., & Levorato, M. C. (1998). The effect of semantic analyzability of idioms in metalinguistic tasks. Metaphor and Symbol, 13(3), 159177. Carnine, D., Kameenui, E. J., & Coyle, G. (1984). Utilization of contextual information in determining the meaning of unfamiliar words. Reading Research Quarterly, 19(2), 188204. Coulmas, F. (1981). Idiomaticity as a problem of pragmatics. In Parret, H., Sbis, M., & Verschueren, J. (Eds.), Possibilities and limitations of pragmatics: Proceedings of the Conference on Pragmatics, Urbino, July 814, 1979 (pp. 139151). Amsterdam: Benjamins. Cramer, D. (1994). Introducing statistics for social research. Step-by-step calculations and computer techniques using SPSS. New York: Routledge. Fox, C., Manning, E., Murphy, M., Urbom, R., & Cleveland Marwick, K. (Eds.) (2004). Longman dictionary of contemporary English. Harlow: Longman. Fraser, B. (1970). Idioms in a transformational grammar. Foundations of Language, 6(1), 2242. Geeraerts, D. (1995). Specialisation and reinterpretation in idioms. In Everaert, M., van der Linden, E-J, Schenk, A., & Schreuder, R. (Eds.), Idioms. Structural and Psychological Perspectives (pp. 5774). Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Gibbs, R. W. Jr., Bogdanovich, J. M., Sykes, J. R., & Barr, D. J. (1997). Metaphor in idiom comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language, 37(2), 141154. Gibbs, R. W., & Nayak, N. P. (1989). Psycholinguistic studies on the syntactic behavior of idioms. Cognitive Psychology, 21(1), 100138. Gibbs, R. W., & O'Brien, J. (1990). Idioms and mental imagery: The metaphorical motivation for idiomatic meaning. Cognition, 36(1), 3568. Glucksberg, S. (1993). Idiom meanings and allusional context. In Cacciari, C., & Tabossi, P. (Eds.), Idioms: Processing, Structure, and Interpretation (pp. 326). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Hulstijn, J. H. (1992). Retention of inferred and given word meanings: Experiments in incidental vocabulary learning. In Arnaud, P. J. L., & Bjoint, H. (Eds.), Vocabulary and applied linguistics (pp. 113125). London: Macmillan. Irujo, S. (1984). The effects of transfer on the acquisition of idioms in a second language. Doctor of Education thesis. Boston University. UMI. Irujo, S. (1993). Steering clear: avoidance in the production of idioms. IRAL, 31(3), 205-19. Keysar, B., & Bly, B. M. (1995). Intuitions of the transparency of idioms: Can one keep a secret by spilling the beans? Journal of Memory and Language, 34(1), 89109. Keysar, B., & Bly, B. M. (1999). Swimming against the current: Do idioms reflect conceptual structure? Journal of Pragmatics, 31(12), 15591578. Kvecses, Z., & Szab, P. (1996). Idioms: a view from cognitive semantics. Applied Linguistics, 17(3), 326355. Lennon, P. (1998). Approaches to the teaching of idiomatic language. IRAL, 36(1), 1130. Nunberg, G. (1977). The pragmatics of reference. Dissertation. New York: City University of New York Center. Nunberg, G., Sag, I. A., & Wasow, T. (1994). Idioms. Language, 70(3), 491538. Sinclair, J. (1995). Collins COBUILD dictionary of idioms. London: HarperCollins. Skoufaki, S. (2006). Investigating idiom instruction methods. PhD dissertation. University of Cambridge.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

35

Skoufaki, S. (2008). Conceptual metaphoric meaning clues in two idiom presentation methods. In Boers, F., & Lindstromberg, S. (Eds.), Cognitive linguistic approaches to teaching vocabulary and phraseology (pp. 101132). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Strassler, J. (1982). Idioms in English. Tbingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. Wesche, M., & Paribakht, T.S. (1998). The influence of task in reading-based L2 vocabulary acquisition: Evidence from introspective studies. In Haastrup, K., & Viberg, . (Eds.), Perspectives on lexical acquisition in a second language (pp. 1959). Lund: Lund University Press.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

APPENDIX A FILLER TEXTS 1. Pauls party was a great success! He had invited many people and nearly all of them came! Fortunately, his house stood alone on top of a hill, so there was no neighbour to complain about the music, the shouting and the laughter that went on till morning. He always mentioned it, later on, as the party where the guests had a lot of fun and raised the roof! 2. Although Mary was very intelligent and had her own opinions about many topics, she always tried to stop having a conversation with someone when she felt it would turn into an argument. She was afraid that people would dislike her. The result was, however, that people thought she was hypocritical and arrogant. In the end, she started to fight her corner. 3. When Helen became the head of the ZEUS TV channel, nobody there expected she would keep things under control. They were fooled by her slender figure and kind face. They soon found out that Helen wanted to set high standards for the quality of the channels programmes. She could become very strict in order to achieve this goal. In all the meetings of the board of directors she criticised the work done so far and demanded better cooperation and more effort. She cracked the whip! 4. John and Gerald were working in the same laboratory when they were undergraduate students at the University. They had to cooperate in order to do certain projects and they cooperated well. One day, John started to make fun of Gerald. He did not mean to be rude. He understood that Gerald was hurt and apologized. Gerald said it was OK. However, from then onwards, John was in bad smell with Gerald.

APPENDIX B IDIOMS AS THEY APPEARED IN (A) THE NO-CONTEXT AND (B) THE CONTEXT CONDITIONS 1. (a) She laid him out in lavender. (b) My mother always had a way of getting us to do what we had to do. When I was 5 years old I hated needles and I always started screaming to keep away from them.

36

SKOUFAKI

One day, my mother and I went to the doctor and when I saw him, I panicked. My mother looked me straight in the eye and commanded me to cooperate. I followed her orders. I think that at that time my fear of mothers scolding was greater than my fear of the doctor. She certainly knew how to lay someone out in lavender. 2. (a) He laid his nuts aside. (b) James had always been a hard worker. When he entered the university, he studied even harder than before, so as to be the best student in his year. He was tempted to go out with his friends or go to a party, but he decided not to and continued studying. His father told him: Im proud of you, but dont be so quick to lay your nuts aside. 3. (a) She has set her cap at him. (b) Jenny thought her work was the most important thing in her life. When she met Chris, she was immediately attracted to him. She always wanted to be near him. In the end they started dating. Having a family was not in her plans. However, not long after that, she set her cap at him, as our mothers say. 4. (a) The goose hangs high. (b) The two farmers walked side by side. That summer the weather had been very good for their plants. They would each begin taking their crops in a few days and it looked like the harvest would be the best ever. There was no sign of a storm that could delay harvest and there were many men and machines to do the work. At the place where they would have to follow opposite directions, John told Olaf: The goose hangs high this year and Olaf agreed. 5. (a) They had him dead to rights. (b) Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, on the seventeenth of October at approximately 5:22 p.m., three people saw this man walk into the bookshop without wearing anything to cover his face. He held up a gun to the woman at the counter and told her he would shoot her if she tried to call security. He then took money from the counter and ran out of the store. We see here a case of armed robbery and attempted murder. Clearly, our countrys justice system has this man dead to rights. 6. (a) It went by the board. (b) The committee was trying to decide which of the projects at the University the government should continue to sponsor. The head of the committee asked whether they should continue sponsoring a certain project in biology. One of the committee members said that they should not sponsor it. He said: At the beginning, the prognosis looked good. Now, I am afraid, this project is out of control. This project is hopeless. It is obvious that it has completely gone by the board. 7. (a) He made a clean breast of it. (b) After so many years of happily married life, Tom cheated on his wife. He did it mainly because he was bored. He was still in love with her. So, he was feeling awful for having done this. In the end, he reached the conclusion that he should make a clean breast of it.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

37

8. (a) He kicked the bucket. (b) Jack seemed a very healthy man. Despite the fact that he was a heavy drinker, he had never had any health problem. He was doing sports very regularly: He jogged every evening and followed kick boxing lessons three times a week. Then, one evening we were shocked to hear that he kicked the bucket. 9. (a) He played the bird with the long neck. (b) Tim lost his favourite toy again. He was sitting looking sad. He expected someone else to find it for him. His grandmother believed that children should learn to do things on their own. So, she did not help him but waited for him to play the bird with the long neck. 10. (a) They cooked her goose. (b) Mary was one of the top students at the university. In the end of her first year at the university, she talked with some of her fellow students about a presentation she was going to give in class. The next day those classmates borrowed all the books that were relevant to her topic from the university library so that she would not be able to give the presentation. So, she had to cancel her presentation. She was sad for a long time after realising that those classmates cooked her goose. 11. (a) She gave him a rocket. (b) Little Jim was very afraid of his parents. So, when he accidentally broke a plate instead of telling his mother, he hid the broken pieces. He was hoping that his mother would not find out about it. In the end, however, his mother discovered the pieces of glass under the sofa. Tim understood that his plan had failed and didnt say anything. She gave him a rocket! 12. (a) They chewed the fat. (b) John spent his summer holiday in Greece on his own. One day, he was very glad to see that one of his fellow travelers on the train was a friend of his from high school. They had not seen each other for ages because they were now working in different cities. They had been away from each other for a long time. However, they very soon started feeling close to each other again. During the rest of the journey they were chewing the fat. 13. (a) We applauded to the echo. (b) A movie review of the 1988 Richman film When Edie killed Fred. This production is a masterpiece. Richman, once again, succeeds in making an interesting film by narrating the unusual, charming, and problematic relationship between two persons with young and freedom-loving minds. This film was so wonderful that I laughed, I cried, I even brought my mother to see it. My mother loved it. Everyone in the theatre loved it. The newspapers reported that the cinema audience all over the world applauded to the echo. 14. (a) It was too hot to handle. (b) Jack is a detective. He has a lot of experience and believes that he can solve any mystery. However, last month a woman came to his office saying that she

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

38

SKOUFAKI

thought her husband had been kidnapped or killed. She said that he did not return from work one afternoon. Jack found out that her husband, apart from working as a bank clerk was also a drug dealer. He immediately decided that he would not go on with that case. He told his client that he found it too hot to handle. 15. (a) She throws mud at them. (b) Mark and Tom had come to the company at the same time. However, Tom was smarter and more hard-working and he got promoted. Mark was very jealous about Toms promotion. He was also very popular with everyone, including the boss. So, Mark decided that, to get Tom fired, he would have to throw mud at Tom.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

16. (a) They have set the ball rolling. (b) John and his friends were trying to write an essay that they had to do as a group. It was their first long essay in the university and they were not sure on how to do it. Although they had all collected the necessary data and had done a lot of thinking about it, they could not start writing it. After a long period of silence, John proposed they should do a plan of the essay writing what each chapter should contain. The rest agreed and were relieved that someone had finally set the ball rolling. 17. (a) He holds all the cards. (b) Mary and Fred were discussing the current state of politics around the world. At some point the discussion turned to the issue of economic development. Mary said that the European Union is a threat against America, because America is already too developed to be able to compete with the European countries. Fred disagreed. He just said slowly and calmly without explaining his opinion: The US will hold all the cards for a long time. 18. (a) We will lighten the load. (b) John, Mary and Philip were classmates at the university. One day, they met at a coffee shop to chat. At some point, they started talking about the exams at the end of the following month. Although they were good students, they thought that the books and articles they had to read for the exams were too many. Mary said they should cooperate. She told the guys: Each of us can read one third of the material and at the end of each week we can meet and exchange notes on what we have read. This way, I think that we will hopefully be able to somehow lighten the load. 19. (a) It stood or fell by that. (b) American film producer David Oliver Selznick tried for years to find the actress to play the role of Scarlett OHara in his most famous film, Gone with the Wind. To decide which actress would play the role, he had various famous actresses act in certain scenes of the film but he kept on being dissatisfied with their acting. He finally decided that Vivian Lee would play the part. However, even during the shooting he was constantly giving her advice on how to act. He strongly believed that such a film stood or fell by the leading actresss performance.

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

39

20. (a) He has taken his place. (b) Like so many artists, Vincent van Gogh was not successful during his lifetime. People did not appreciate his painting style, so he was very poor. However, he was so devoted to his art that he painted to the point of exhaustion. This led him to a nervous breakdown and he was put into a psychiatric asylum. He continued to paint there as well. In the twentieth century, his work started to be considered unique and radically different from that of his contemporaries and now his paintings are very expensive. Not only because of his genius, but also thanks to todays views on art, he has taken his place as an artist.

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

21. (a) They praised him to the skies. (b) The Greek writer Yannis Skaribas had a very successful career right from the beginning. His first novella, The Sacred Ram, was considered by critics and fellow writers as the Greek masterpiece of Modernism. The works which he produced afterwards were not so successful. Back then, all magazines praised him to the skies. 22. (a) They were heading for a fall. (b) The conservative partys course in the government started well. However, they kept on making mistakes in all sectors after a certain time. The lack of a strong profile in foreign affairs and the increase in taxes decreased its popularity. Also, a sex scandal of one of the ministers damaged the partys reputation. It was obvious that they were heading for a fall. 23. (a) It reached boiling point. (b) Ben never really liked Sam. Sam often made fun of Ben in front of others and especially in front of the girl they both liked. In the end of the year, Sam started dating her and referred to her often in conversations with Ben to make him jealous. One day, he said that she obviously had too good taste in men to date Ben. Everyone in the room could feel that the situation had finally reached boiling point. 24. (a) She had her knife into him. (b) Mary and Jane were close friends in high-school. They knew each others secrets and seemed inseparable. However, their friendship collapsed when they fell in love with the same guy. Soon, Jane started dating him. Mary revealed little by little all of Janes secrets to the whole class and gave Jane wrong advice when they studied together. She pretended to be Janes best friend and was very sweet to Jane, but she had her knife into Jane.

40

SKOUFAKI

APPENDIX C INSTRUCTIONS IN THE JUDGES DEFINITION CATEGORIZATION TASK You are given sheets, each of which has written at its top the initials of each of the participants in the experiment. The participants first task was to guess the meanings of idioms after first answering the question Do you know the meaning of this idiom?. You are asked to categorise their responses. You are asked to place each response of each participant in one of the following categories:

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012

a. literal interpretation (when you think a participant has interpreted an idiom literally) For example, supposing that one were given the idiom to spill the beans, which means to reveal a secret, and he or she wrote the following definition for the idiom: to spill by accident the beans that were boiling in the saucepan, this definition should be categorised as a literal one. b. correct interpretation (when you think a participant has guessed an idioms meaning) The answer neednt be identical to the one I have given for each idiom but they should both convey the same overall meaning. c. possible interpretation (when you think the interpretation a participant gave is not the correct one but seems a reasonable guess, because, for instance, it is warranted by some interpretation of a word or words) In some cases, the definition will be enough to show you whether it is possible, but there may be cases where the definition is too brief to let you draw a conclusion about its plausibility. In these cases, look at the explanation the participant has given about how he or she reached this definition to find evidence for or against the plausibility of the definition. For example, in a similar experiment, a participants definition for the idiom to hose down, which means to rain heavily, was to defeat someone in a game. In the explanation given about how he or she reached this interpretation, he or she wrote that hose is related to clean, so he or she thought it meant to clean somebody up, which means to defeat someone. Whenever you need to check the participants explanations of how they came up with their definitions, go to the last part of their booklets. d. no answer/nonsense. Please circle one of these alternatives written after each idiom on the sheet for each participants responses.

APPENDIX D INSTRUCTIONS TO THE JUDGE WHO CATEGORIZED THE PARTICIPANTS IDIOM INTERPRETATIONS IN EXPERIMENT 17 Your task is to categorise the definitions listed next to each idiom into meaning categories you yourself will create. To do so, please read through the definitions for each idiom and write the categories of definitions you will come up with at the first row provided underneath the definitions.

7

The task was done electronically and the list of texts referred to in the instructions is the same as in Appendix B.

INVESTIGATING THE SOURCE OF IDIOM TRANSPARENCY INTUITIONS

41

Downloaded by [American University in Cairo] at 14:22 19 March 2012