Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Civ Pro Barbri

Hochgeladen von

Es AzcuetaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Civ Pro Barbri

Hochgeladen von

Es AzcuetaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1/15/2012 11:02:00 PM Civ Pro Barbri VI.

Pleadings documents filed that states claims and defenses Section A- Complaint -Filed by P -Filing this is what starts the case Requirements are in Rule 8A 1. statement of SMJ 2. short and plain statement of the claim 3. make demand for relief- money, injunction.. etc **8A2- short and plain statement of the claim -Historically the federal rules used notice pleading to simply give enough detail to give the other side notice, not a whole lot of detail -Federal rules have always avoided the word facts bc a lot of state laws had required fact pleading and the idea of fact gave people a hard time -Federal rule relied on notion to give notice All of that changes with Twombly and Iqbal (Twiqbal) -this has imposed a higher standard, a tougher burden, for P to state a claim Twiqbal 1. ignore conclusions of lawthe court will ignore conclusions of law. If P, in her complaint makes a conclusion of law, they will ignore it. Ex. D was reckless or conspired 2.** P must plead facts supporting a plausible claim -kind of odd because rule 8 has never required pleading of fact. Look only at allegations of fact, facts supporting a PLAUSIBLE claim not just possible. Not enough that it is possible, it must be plausible 3. court will use its own experience and common sense to determine if a claim is plausible -allows great discretion in trail judge -resulted in a lot more challenges to pleadings, now you need facts supporting a plausible claim.

-*certain areas in which you have to plead in greater detail 9B 9G -have to give particulars 9B allegations of fraud or mistake must be made with particularities, you have to give chapter inverse (dates, what the other party said, details on fraud and mistake) 9G give details on items of special damage, give in detail in specificity special damage- exceptional and does not ordinary flow so you need a special detail B. D response Governed by Federal Rule 12 -when you get sued, you have a choice of how to respond -which ever choice you make, you have to respond within 21 days of service of process -respond by (1.) motion or (2.) by answer -whichever one you do must be done in 21 days -motion is not a pleading -motion is a request for court to order something and during a litigation there may be dozens of motions. Every time you ask the court to order something, you are asking the court to make a motion. Motion is not a pleading. Motion under Rule 12 -two are very specialized -12E and 12F 12E motion for more definite statement, pretty rare. Complaint is unintelligible -12F motion to strike, any party can bring a motion. Cut out things that dont belong in the pleading. For example maybe a party has demanded a jury trail but there is no right to a jury trail you can get a motion to strike if it is inappropriate 12B - list of 7 defenses

-all of those can come up as motions to dismiss -the motion is not a pleading, BUT the answer is a pleading -*rule 12B tells us that those 7 defenses can be raised either by motion or by answer -important because it gives rise to possibility of waiver 12B DEFENSES (1.) 12B1- SMJ (2.) 12B2- PJ (3.) 12B3- Venue (4.) 12B4- Insufficient process (fairly unlikely) -process is summons and copy of complaint. 12B4 is when there is a problem with one of those documents (5.) 12B5- Insufficient service of process- documents were fine but they were not served correctly *(6.) 12B6- failure to state a claim (7.) 12B7- failure to join an indispensible party (party under Rule 19) **12G and H read together impose strict rules about waiver -not at all clear on its face 1. 12B2,3,4,5 MUST be put in your FIRST rule 12 response or they are waived -Rule 12 response- rule 12 motion or answer -these are called the waivable defenses 2. 12B6,7 can be raised for the first time anytime through trial, do not have to be in first rule 12 response. Raise these no later than at trial, cant raise first time in appeal for example 3. 12B1 can be raised anytime in the case, SMJ. That defense is never waived. Can raise it for the first time on appeal. If we do not have SMJ, it is unconstitutional under Article 3 of Constitution P sues D -D within 21 days makes a motion to dismiss for insufficient service of process Under Rule 12B5 -court hears motion and denies it, we wont dismiss, service was ok

-D files her answer - she says there is no PJ and no venue -she waived PJ and Venue because they are waivable C. ANSWER 1. under 8B you must respond to the complaint go through everything P said in complaint and respond 1. admit 2. deny 3. lack sufficient information only do that if the stuff is not in your control or not public knowledge ***Failure to deny is an admission. True on everything except damages 2. raise affirmative defenses 8C1 -affirmative- raising a new fact, if you are right, you the D, win ex. statute of limitations, statute of frauds. No matter what I did, you cannot win because the statute of limitations has run -have to plead affirmative defenses -D has burden -If you do not plead them you run the risk of waiver ***In answer, we response and we assert affirmative defenses -denial reacting to what P said, not injecting new facts Affirmative Defenses SOL SOF -you have to pleade affirimitve defenses, defendant must assert this pleading in their answer, if not then D runs the risk of waiver Answer -respond to allegations and assert affirmative defenses

1/15/2012 11:02:00 PM VII. Joinder: Joinder rule defines the scope of the case, they tell us how big, how many claims, and how many parties in one case -great vehicle for testing SMJ -every single claim in federal court has to have federal SMJ (A.) claim joinder by P Rule 18(a) -the P can join any claim she has against D, there is no limit, dont have to be related at all ex. breach of contract, unrelated tort, and personal injury -you do not have to assert all of those, but you may *Then assess SMJ -can the case as structured get into federal court (B.) Claim joinder by D -D is going to sue someone, D is asserting a claim against some party Analytical Framework: Counter Claim v Cross Claim i. Counter claim- asserted against an opposing party, claim goes against someone who has sued you 13(a)(1)- Compulsory Counter Claim arises from same T/O as P claim; must assert that claim in this case or else you waive the claim. This is the only compulsory claim in the world Ex. A and B driving around in their car, they collide. Case 1 A sues B, someone wins. Case 2 B sues A about same wreck. That case is dismissed because It is a compulsory counterclaim and B should have asserted the claim in the first case, we failed to do it, so the claim is lost. 13(b)- Permissive Counter Claim, does not arise from same T/O as P claim. May assert not must 1. **Must have SMJ Diversity and must exceed 75k FQ

If no SMJ, then what about SJ? 2. What about Supplemental Jurisdiction? -you only need supplemental jurisdiction if you have a case that does not meet FQ or diversity 3. 1367(a)- does it grant jurisdiction? Codifies Gibbs, Gibbs is CNOF all from the same real world effect. T/O always meets Gibbs, so compulsory counterclaims must meet Gibbs Now, if 1367 grants it does 1367(b) take jurisdiction away? 4. Does 1367(b) take it away? -only applies in diversity case **-only takes away Supplemental Jurisdiction claims made by P, not by D ii. Cross Claim- claim against a co-party, not opposing. Must arise from same T/O as the underlying case; never compulsory Rule 13(g) SMJ? SJ? Cross claims always meets 1367(a) Does 1367(b) take it away?

Proper Parties: Who may be joined? -Rule 20(a)(1)Co-plaintiffs ** we may join together because our claims arise from the same T/O and they raise at least on common question -we may join together, but are not required to -Rule 20(a)(2) Co-defendants ** we may join together because our claims arise from the same T/O and they raise at least on common question Next, must assesses SMJ; can the case get into federal court? (D.) Necessary and Indispensible; who MUST be joined

-Rule 19 1. Is absentee necessary/required? The answer is yes if we meet any of three tests found in 19(a)(1) 19(a)(1)- go through these three tests o 19(a)(1)(a) without absentee, the court cannot accord complete relief among the parties. Looking at efficiency, hoping to avoid separate litigation o *19(a)(1)(b)(1) the absentees interest may be harmed if she is not joined; focusing on absentees interest herself o 19(a)(1)(b)(2) absentees interest may subject D to a risk of multiple of inconsistent interests/ obligations **if you meet any of those three tests, then absentee is necessary and required to be brought in -Joint tort-feasors are never necessary (Temple) 1. is absentee necessary? If yes, then go to step 2 2. Is joinder of absentee feasible? -Need personal jurisdiction -Need subject matter jurisdiction- will bringing absentee destroy diversity? 3. Here, presume the absentee cannot be joined. She is necessary but we cant because there is no PJ or SMJ. Joinder not feasible; court must make a choice: Proceeds without absentee or court dismisses entire case Rule 19(b) - we should not dismiss this case unless P has an alternative forum -if we dismiss, can P get that justice somewhere -if court dismisses, we call absentee indispensible. Motion 12(b)(6) (E.) Impleader Rule 14 -a defending part(someone thats been sued) joins a new party(TPD) -TPD may be liable to D for the P claim

-this boils down to indemnity or contribution, joining someone to deflect liability -not between co-parties, joining new party Rule 14(a) - P may assert claim against TPD as long as it arises from same T/O - TPD can assert a claim down against P, must arise from same T/O - Claim by D (impleader), P against TPD, TPD against P

1/15/2012 11:02:00 PM Judge will instruct jury on the law but the jury determines the facts Bench trail: no jury sitting, judge decides the fact Right to a jury trail -Seventh Amendment applies only in federal civil cases; does not apply in state court or criminal cases preserves the right; does not create or grant, to a jury trail does so only in actions at law not equity stuck with a historical test o depends how it would have been done in 1791 at the common law of England; thats when the 7th amendment was ratified and because it says preserves we must uphold that language o ask would we have had a jury at common law England in 1791 (a.) is there a 1791 analogue to this claim back in England? (b.) **look at the remedy sought o what is P after o law v equity remedies jury at law but not in equity Remedies Damages Compensatory- Money to compensate P for the harm done to him Equity Remedies Injunctions, specific performance, rescission, reformation Orders by the court enforceable by contempt No jury

Beacon Theatre (1959) and Dairy Queen (1962) Rules 1. Determine the jury right issue by issue o we do not go with center of gravity, not all or nothing 2. If an issue of fact underlies law and equity you get a jury 3. Try the jury issues first

Motions: 1. Motion for JMOL (Judgment as a matter of law) Rule 50(a) o Grant this motion if reasonable people could not disagree on the result o Comes up at trail and if evidence is so clear and overwhelming then judge can decide case on in its own o You can only make this motion after the other side has been heard at trail Used to be called Directed Verdict Judge takes the case away from the jury and decides it himself Functional equivalent as summary judgment- it just comes up at a different time *summary judgment comes up before trail here, we are at trail but dont want the jury to have discretion over the case

2. Renewed JMOL Rule 50(b) o Exactly the same as JMOL but it comes up later in the case o Someone moved for JMOL and it was denied and judge let it go to the jury o Jury comes back with an unreasonable verdict, reasonable people could not have reached that conclusion D will move for renewed JMOL Comes up after trail, there has been a judgment and it is a way for D to undo it This motion must be made within 28 days after the entry of the judgment Must have moved for JMOL at a proper time at trail You waive RJMOL unless you move for JMOL at an appropriate time at trail (anytime after other side presents their argument) 3. Motion for new trail 59(a)(1) timing same as JMOL

make motion within 28 days after the entry of the judgment **trail court judge is convinced that something was wrong in that case and it affected the outcome of the case and so we should start over there was a problem when we went to trail and instead of reversing, just do it over anything that convinces the judge that we should start over, maybe he judge made a mistake court can do this on its own sue spote (on its own) this is less drastic that RJMOL because new trail just results in starting over RJMOL is much more radical because it takes the victory away from one party and gives victory to the other party

1/15/2012 11:02:00 PM The object of this Essay is to assert one very simple principle, as entitled to govern absolutely the dealings of society with the individual in the way of compulsion and control, whether the means used be physical force in the form of legal penalties, or the moral coercion of public opinion. That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise. To justify that, the conduct from which it is desired to deter him, must be calculated to produce evil to some one else. The only part of the conduct of any one, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.

The debate over the relationship of law and morality was brought to the fore in the famous Hart/Devlin debate, which followed the publication of the Wolfenden report in 1957. The committee behind the report contained Lord Devlin, a prominent judge, and the academic Professor Hart. The report recommended the legalisation of prostitution and homosexuality on the particularly utilitarian basis that the law should not intervene in the private lives of citizens or seek to enforce any particular pattern of behaviour further than necessary to protect others. Hart, who was influenced by the theories of Mill, supported the reports approach, stating that legal enforcement of a moral code was unnecessary (because a pluralist society wont suddenly disintegrate), undesirable (as it would prevent development of morality), and in fact morally unacceptable (as it interferes with individual liberty). Devlin, on the other hand, was strongly opposed to the report, on what might be cited as a natural law approach. He felt that society had a

certain moral standard, which the law had a duty to support, as society would disintegrate without a common morality (a point which, as we have seen, Hart disagreed with). Devlin felt that this morality should be based on the views of the right-minded person, and that the legislature should adhere to three basic principles: Individuals should be allowed as much freedom and privacy as is possible without compromising this morality; Parliament and the judiciary should be very cautious about altering laws concerning morality, and that punishment should be used to prevent actions abominable to right-minded people; the law should also only state the minimum of acceptable behaviour, society should have far higher standards. Hart objected to this view, questioning what the right-minded view was. He argued that objections to another morality were more often due to prejudice, fear, ignorance, and misunderstanding rather than the rational approach necessary for law. He gave four reasons for not criminalising that which the right-minded person objected to. Firstly, punishment of someone does harm to them, and if their actions have done no harm to anyone else, then this surely cannot be correct. Secondly, free will is very moral, so undue interference with it would be immoral. Thirdly, this free will can allow learning through experimentation, and fourthly, legislation suppressing an individuals sexuality will harm them, as it can affect their emotional nature. Conclusion In conclusion then, we can see that there are various theories on how law and morality should relate to each other. Whether or not the law should uphold the moral values of society is still debated, and is made more difficult as, in a pluralist society, it is difficult to know what moral values should be supported, or should the issue be left alone to preserve individual liberty? The current approach by the legal system seems to be that a common morality, based on traditional, right-minded values should be maintained by the law, as espoused by Devlin. This may be due to a backlash against the liberalising values of the Wolfenden report. Cases such as Shaw v Director of Public Prosecutions (1961) and Knuller v Director of Public Prosecutions (1972) made use of the offence of conspiracy to corrupt public morals (which had not previously been used since the nineteenth century) and signalled that the law would attempt to uphold societys moral

values according to Devlins doctrine. This approach has continued, as the more recent case of R v Brown (1994) shows. The defendants had willingly consented to various sado-masochistic practices, and none of them had complained to the police. Nevertheless, they were prosecuted, and their convictions were upheld by both the House of Lords and the European Court of Human Rights, based on public policy to defend the morality of society. The law is therefore seen to attempt to uphold what it considers to be public morality, even if some may dispute the correctness of that moral code. Evaluating the six concepts of laws demonstrates the differences between idealist and pragmatist philosophies, as illustrated in the Hart-Devlin debate. Devlin's philosophy of legal moralism takes an idealist's approach to role of law in society. Devlin's philosophy of law argued that the collective judgment of a society should guide enforcement of laws against both private and public behavior that was deemed immoral. According to Devlin, when a behavior reached the limits of "intolerance, indignation and disgust," legislation against it was necessary. Hart's philosophy of legal positivism is a pragmatist's approach to the role of law in society. Hart's philosophy of law held that laws should not be based only on popular moral consensus, in the absence of other harms. This is consistent with Hart's argument that one role of law was to protect individual liberty. Devlin argued in The Enforcement of Morals (1959): There is a shared morality in each community (in Devlin's case he meant a morality derived from Christianity.) He argues that private behaviour should be regulated, that things done in private by people to themselves or other consenting persons that go against the public morality do in fact harm the community as a whole because it undermines the community's state of cohesion. If morality is weakened, it tends to lead to the destruction of society. The public morality, Devlin believes, will be shown through public outrage and the unanimous condemnation of a jury. "No society can do without intolerance, indignation and disgust" Hart argued in Law, Liberty and Society (1963) that:

Humanity incorporates into it's legal systems a "minimum content of natural law" all systems have laws against theft, violence and unmitigated killing. However this is not an expression of common morality but rather of a necessity to prevent certain harmful acts. That is common to all groups, it is an embodiment of John Stuart Mill's Harm Principle. Further there can be no morality common to the entire populace, many societies are pluralistic in matters of morality (outside of the minimum content of natural law which allows society to function) "especially with regard to sexual morality, and that 'difference' in such matters is not necessarily harmful to society it could be argued to be beneficial".

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- MPRE Unpacked: Professional Responsibility Explained & Applied for Multistate Professional Responsibility ExamVon EverandMPRE Unpacked: Professional Responsibility Explained & Applied for Multistate Professional Responsibility ExamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Draft 2Dokument12 SeitenShort Draft 2Rishabh AgnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CivPro Law in A Flash Outline of BLLDokument2 SeitenCivPro Law in A Flash Outline of BLLjohngsimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Analysis of Evidence ProblemsDokument4 SeitenSummary Analysis of Evidence ProblemsJames MortonNoch keine Bewertungen

- EPA Impact Study LawsuitDokument8 SeitenEPA Impact Study Lawsuittoka sadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civ Pro 2 Worksheet 2Dokument9 SeitenCiv Pro 2 Worksheet 2Victor MastromarcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure SkeletonDokument8 SeitenCivil Procedure SkeletonTOny AwadallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Graham Evidence Spring2013 2Dokument26 SeitenGraham Evidence Spring2013 2sagacontNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Causes of Action and Complaint FilingDokument4 SeitenUnderstanding Causes of Action and Complaint FilingHarvey Leo RomanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 13. Counterclaim and CrossclaimDokument8 SeitenRule 13. Counterclaim and CrossclaimJosh YoungermanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence One PagerDokument3 SeitenEvidence One PagerTheThemcraziesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Bar Exam Game Plan: Optimizing Your Review TimeDokument5 SeitenThe Great Bar Exam Game Plan: Optimizing Your Review TimeJastin GalariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBEQuestions1998 PDFDokument103 SeitenMBEQuestions1998 PDFMarco FortadesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fall Civ Pro I OutlineDokument31 SeitenFall Civ Pro I OutlineNicole AlexisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civ Pro Spring Attack SheetsDokument9 SeitenCiv Pro Spring Attack SheetsadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- PJ and DiversityDokument2 SeitenPJ and DiversityjuicykeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Outline FinalsDokument16 SeitenCivil Procedure Outline FinalsKristi JacobsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pleading Requirements for Protestor Removal CaseDokument8 SeitenPleading Requirements for Protestor Removal CaseDeserae WeitmannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline-Civ.-pro II (Very Thorough)Dokument37 SeitenOutline-Civ.-pro II (Very Thorough)adamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crim Pro OutlineDokument22 SeitenCrim Pro Outlinemichael bradfordNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Law: 33 Questions on Federal Judicial AuthorityDokument39 SeitenConstitutional Law: 33 Questions on Federal Judicial AuthoritytNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Law Cheat Sheet: by ViaDokument3 SeitenConstitutional Law Cheat Sheet: by ViaMartin LaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Babich CivPro Fall 2017Dokument30 SeitenBabich CivPro Fall 2017Jelani WatsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence AND: Evidence Outline W/O Hearsay I. Relevance (FRE 401 and 403)Dokument12 SeitenEvidence AND: Evidence Outline W/O Hearsay I. Relevance (FRE 401 and 403)no contractNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIVPROOUTLINEFINALDokument42 SeitenCIVPROOUTLINEFINALJason MaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- CharacterDokument15 SeitenCharacterZarah TrinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence Class Outline 2 (1584)Dokument73 SeitenEvidence Class Outline 2 (1584)Tiffany BrooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIV PRO BARBRI NOTES EditedDokument16 SeitenCIV PRO BARBRI NOTES EditedTOny AwadallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure OutlineDokument18 SeitenCivil Procedure OutlineLanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Cheat Sheet: by ViaDokument3 SeitenCivil Procedure Cheat Sheet: by ViaMartin LaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stage Issue Rule Description Related Cases/Rules: Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rules ChartDokument11 SeitenStage Issue Rule Description Related Cases/Rules: Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rules ChartJo Ann TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civ Pro Yeazell Fall 2012Dokument37 SeitenCiv Pro Yeazell Fall 2012Thomas Jefferson67% (3)

- OR OR: Subject Matter JurisdictionDokument4 SeitenOR OR: Subject Matter JurisdictioncdslamcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Mbe AnswersDokument10 SeitenCriminal Mbe AnswersStacy MustangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parties. ALIENAGE If One Party Is Citizen of Foreign State, Alienage Jdx. Satisfied, Except WhenDokument2 SeitenParties. ALIENAGE If One Party Is Citizen of Foreign State, Alienage Jdx. Satisfied, Except WhenCory BakerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Mentor OutlineDokument7 SeitenCivil Procedure Mentor OutlineLALANoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Evidence 7 04 Sample AnswerDokument4 Seiten2 Evidence 7 04 Sample AnswerZviagin & CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pleadings ExplainedDokument20 SeitenPleadings ExplainedEveris HolbienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benjamin v. Lindner Aviation Case StudyDokument16 SeitenBenjamin v. Lindner Aviation Case StudyMissy MeyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agency & Partnership LiabilitiesDokument147 SeitenAgency & Partnership LiabilitiesAndrew FergusonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Procedure Epstein Fall 2009-1Dokument16 SeitenCriminal Procedure Epstein Fall 2009-1dicleverNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hilton v. Guyot and Pennoyer v. Neff case digestDokument5 SeitenHilton v. Guyot and Pennoyer v. Neff case digestNeill Matthew Addison OrtizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Jurisdiction and ProcedureDokument9 SeitenFederal Jurisdiction and Procedurerdatta01Noch keine Bewertungen

- Classification of Remedies (Outline)Dokument4 SeitenClassification of Remedies (Outline)Ronnie Barcena Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Relevance and Admissibility of EvidenceDokument18 SeitenRelevance and Admissibility of EvidenceksskelsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Improper Bargaining Step by StepDokument3 SeitenImproper Bargaining Step by StepLazinessPerSe100% (1)

- CP Week 8 NotesDokument23 SeitenCP Week 8 NotesRooter CoxNoch keine Bewertungen

- KP FRCP Fall Civ ProDokument14 SeitenKP FRCP Fall Civ ProadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chart End ProblemDokument2 SeitenChart End Problemmtaylor404Noch keine Bewertungen

- My Civ Pro Outline1Dokument25 SeitenMy Civ Pro Outline1topaz551Noch keine Bewertungen

- Crim. Law ATTACK Outline - Alschuler - Spring 2009 ChecklistDokument8 SeitenCrim. Law ATTACK Outline - Alschuler - Spring 2009 ChecklistDaniel BarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Big Head Civ ProDokument55 SeitenBig Head Civ ProSucolTeam6Noch keine Bewertungen

- Crim Law OutlineDokument9 SeitenCrim Law OutlineEmma Trawick BradleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBE - TortsDokument16 SeitenMBE - TortsMichael FNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Resp ExamDokument5 SeitenProfessional Resp ExamMaybach Murtaza100% (1)

- Professional Responsibility: Outline: Disclaimer: These Notes and Outlines Are Provided AsDokument16 SeitenProfessional Responsibility: Outline: Disclaimer: These Notes and Outlines Are Provided AsdigitldrewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drobak CivPro Foster Spring06Dokument42 SeitenDrobak CivPro Foster Spring06HollyBriannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Degroat Crim Adjudication OutlineDokument22 SeitenDegroat Crim Adjudication OutlineSavana DegroatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence CapraDokument87 SeitenEvidence CapraGuillermo FrêneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bedding F-702 NEWDokument2 SeitenBedding F-702 NEWBADIGA SHIVA GOUDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 18 Section 3Dokument8 SeitenChapter 18 Section 3api-206809924Noch keine Bewertungen

- Incrementnotes PDFDokument6 SeitenIncrementnotes PDFnagalaxmi manchalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The ProprietorDokument3 SeitenThe ProprietorBernard Nii Amaa100% (1)

- Presented By:: Reliance Industries Limited and Reliance Natural Resource Limited DisputeDokument20 SeitenPresented By:: Reliance Industries Limited and Reliance Natural Resource Limited DisputeTushhar SachdevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit Nature of ContractDokument102 SeitenUnit Nature of ContractdanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- 74th AmendmentDokument23 Seiten74th Amendmentadityaap100% (3)

- Churchill v Concepcion: Philippine Supreme Court upholds tax on billboardsDokument2 SeitenChurchill v Concepcion: Philippine Supreme Court upholds tax on billboardsKent A. AlonzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code of Ethics and Guidelines Iaap: I. Analyst-Patient RelationshipsDokument4 SeitenCode of Ethics and Guidelines Iaap: I. Analyst-Patient RelationshipsChiriac Andrei TudorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Echeverria Motion For Proof of AuthorityDokument13 SeitenEcheverria Motion For Proof of AuthorityIsabel SantamariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Implementasi Rekrutmen CPNS Sebagai Wujud Reformasi Birokrasi Di Kabupaten BogorDokument14 SeitenImplementasi Rekrutmen CPNS Sebagai Wujud Reformasi Birokrasi Di Kabupaten Bogoryohana biamnasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bill of Rights Sec 1Dokument295 SeitenBill of Rights Sec 1Anabelle Talao-UrbanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovative Financing of Metro Rail ProjectsDokument8 SeitenInnovative Financing of Metro Rail ProjectsNivesh ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIABILITYDokument8 SeitenLIABILITYkaviyapriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs de Los SantosDokument8 SeitenPeople Vs de Los Santostaktak69Noch keine Bewertungen

- Revenue vs Capital Expenditure and Capital AllowancesDokument4 SeitenRevenue vs Capital Expenditure and Capital AllowancesLidia PetroviciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuldague vs. Judge PardoDokument13 SeitenTuldague vs. Judge PardoAngelie FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written Task 1 - Child Pornography in CartoonsDokument4 SeitenWritten Task 1 - Child Pornography in CartoonsMauri CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feria Vs CADokument2 SeitenFeria Vs CAClaudine BancifraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing Case Notes: A Very Brief Guide: Kent Law School Skills HubDokument1 SeiteWriting Case Notes: A Very Brief Guide: Kent Law School Skills HubAngel StephensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employment Contract Know All Men by These Presents:: WHEREAS, The EMPLOYER Is Engage in The Business ofDokument3 SeitenEmployment Contract Know All Men by These Presents:: WHEREAS, The EMPLOYER Is Engage in The Business ofHoney Lyn CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plato and Rule of LawDokument23 SeitenPlato and Rule of LawIshitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senior-citizen tax discounts clarifiedDokument2 SeitenSenior-citizen tax discounts clarifiedJianSadakoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prepositions Exercise ExplainedDokument4 SeitenPrepositions Exercise Explainediwibab 2018Noch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Services Act 2007Dokument114 SeitenFinancial Services Act 2007Farheen BegumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bache & Co Phil Inc v. RuizDokument3 SeitenBache & Co Phil Inc v. RuizRobby DelgadoNoch keine Bewertungen

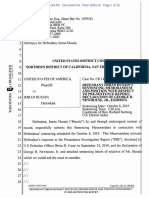

- Imran Husain Sentencing Memo Oct 2019Dokument15 SeitenImran Husain Sentencing Memo Oct 2019Teri BuhlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sworn Statement of Accountability of The PreparersDokument2 SeitenSworn Statement of Accountability of The PreparersLugid YuNoch keine Bewertungen

- IRS Allotment Dependency by Philippine Province 2009-2018Dokument10 SeitenIRS Allotment Dependency by Philippine Province 2009-2018Rheii EstandarteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schedule G Ownership DetailsDokument2 SeitenSchedule G Ownership DetailsMoose112Noch keine Bewertungen