Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Anastomosis Intratoracica Esofago-Gastrica

Hochgeladen von

Odalis ArambuloOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Anastomosis Intratoracica Esofago-Gastrica

Hochgeladen von

Odalis ArambuloCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Intrathoracic Linear Stapled Esophagogastric Anastomosis: An Alternative to the End to End Anastomosis

Lyall A. Gorenstein, MD, Marc Bessler, MD, and Joshua R. Sonett, MD

Department of Surgery, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Division of Minimally Invasive Surgery, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, New York

Minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) is gradually gaining acceptance as an oncological sound procedure. The advantages of MIE arise from avoidance of a thoracotomy or laparotomy, resulting in decreased pulmonary morbidity and generally a faster recovery, yet not compromising the surgical benet of esophagectomy in patients with cancer of the esophagus. No single technique of esophagectomy has proven itself superior to another

from either an oncologic or survival perspective. The MIE is a technically demanding procedure that requires advanced endoscopic skills, especially when performing an intrathoracic anastomosis. We present an alternative intrathoracic anastomotic technique to the commonly performed EEA anastomosis. (Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:314 6) 2011 by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

T

FEATURE ARTICLES

here are various approaches to a minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) [1 4], as there are with an open esophagectomy. With the increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction, a minimally invasive IvorLewis esophagectomy is an excellent procedure in that it affords wide resection margins, complete celiac dissection, and mediastinal lymph node dissection. Compared with a minimally invasive transhiatal esophagectomy or three-hole esophagectomy, there is a lower incidence of recurrent laryngeal injury and better swallowing in the immediate postoperative period. Performing a reliable minimally invasive intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis is challenging. In general, most Ivor Lewis resections for esophageal cancer currently being performed use standard established anastomotic techniques, which are very reliable and have a low incidence of anastomotic leaks or postoperative strictures [5]. However, the commonly performed two-layered hand-sewn anastomosis can not be easily adapted to a minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. Most centers performing a minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy use the EEA stapler. There are certain technical aspects to using this stapler when performing an MIE, which can be challenging; these aspects include inserting an adequate-sized EEA instrument through a narrow intercostal space, placing the anvil into a nondilated esophagus, and intracorporeal suturing of the pursestring to hold the anvil in place. As our experience in MIE increased, our anastomotic technique

evolved from a partially hand-sewn anastomosis to a completely linear stapled anastomosis.

Technique

During the intra-abdominal component of the mobilization, the gastric tube is initiated, but not completed. A double lumen endotracheal tube is inserted, and the patient is placed in a left lateral decubitus position supported by a bean bag. The table is exed maximally to allow placing the thoracoscope in the eighth or ninth intercostal space. Rotating the patient toward the left until they are nearly prone displaces the lung without the need for an additional port to retract the lung. We place our 5-cm utility incision opposite the azygous vein as far anteriorly as possible, usually in the fourth intercostal space. A third port is placed just inferior to the scapula (Fig 1). The azygous vein is divided with a linear stapler. The esophagus is mobilized approximately 5 to 7 cm above the azygous vein, maintaining the dissection adjacent to the longitudinal muscle so that the recurrent laryngeal nerves or membranous trachea are not injured. The esophagus is divided with the harmonic stapler above the azygous vein. We than complete the gastric tube staple line with the linear stapler. The esophagogastectomy specimen is placed in a large specimen bag and is retrieved through the utility port. We routinely open the specimen to examine the gross surgical margin prior to having the pathologist evaluate the microscopic margin. The gastric conduit is placed posterior to the divided esophagus. Adequate esophageal mobilization is essential to allow the esophagus to overlap 4 to 5 cm onto the stomach. The tip of the stomach should lie at the apex of the chest, which will prevent redundancy of the conduit

0003-4975/$36.00 doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.02.115

Accepted for publication Feb 26, 2010. Presented at the Surgical Motion Picture Session of the Fifty-sixth Annual Meeting of the Southern Thoracic Surgical Association, Marco Island, FL, Nov 4 7, 2009. Address correspondence to Dr Sonett, 161 Fort Washington Ave, New York, NY 10032; e-mail: js2106@columbia.edu.

2011 by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Published by Elsevier Inc

Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:314 6

HOW TO DO IT GORENSTEIN ET AL LINEAR INTRATHORACIC ANASTOMOSIS

315

Fig 1. Left lateral decubitus positioning with extreme anterior rotation of the table. The specimen is removed through the anterior port, and the linear stapler is used to nish the anastomosis.

Fig 3. The linear stapler is introduced through the posterior/inferior port.

Comment

There are several features of this technique that are unique and vary from the EEA anastomosis. The anterior utility incision, which is used to perform the majority of the dissection, allows retrieval of the specimen and closure of the anterior gastrotomy of the anastomosis. Because it is placed more anteriorly, the intercostal space is wider, which allows several instruments to be simultaneously inserted through it. In addition to being very functional, we also nd the more anterior intercostal

Fig 2. Stay sutures placed with the endostitch align the stomach and the esophagus.

FEATURE ARTICLES

and improve gastric emptying. The harmonic stapler is used to perform a transverse gastrotomy. Interrupted stay sutures are placed at the corners of the anastomosis (Fig 2). The sutures are used as stay sutures brought out

through the most posterior anterior port sites. The linear stapler is placed through the inferior port, which is aligned with the anastomosis. Traction on the stay sutures facilitates inserting the linear stapler (Fig 3). We create a 4-cm staple line between the stomach and the esophagus (Fig 4). A third stay suture is placed in the anterior defect midway between the two corner sutures. The anterior defect can usually be closed with a single ring of the linear stapler placed through the anterior utility incision (Fig 5). After completing the anastomosis, an upper endoscopy across the anastomosis insures that there is no torsion of the stomach and that the anastomosis is adequate. If it seems that there is a redundant stomach in the right chest, we will gently push the excess stomach back into the abdomen. Preventing the redundant stomach from bowing into the pleural space greatly improves gastric emptying and postoperative quality of life. Suturing the stomach to the right crus of the diaphragm reduces the risk of intestinal hiatal hernias postoperatively.

316

HOW TO DO IT GORENSTEIN ET AL LINEAR INTRATHORACIC ANASTOMOSIS

Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:314 6

incisions are less painful. The linear stapler is simpler to manipulate in the pleural space than by using an EEA device. There are several difcult steps to successfully create an endoscopic intrathoracic EEA anastomosis; namely, these steps involve inserting the anvil into the esophagus, the pursestring suture that holds it in place, and attaches the anvil to the stapler. Unless a large EEA anastomosis is made, there is a risk of postoperative dysphagia if any scarring develops at the anastomosis. The linear side-to-side anastomosis that is described here is large and rarely stenotic. As our experience with MIE has increased, our techniques have also evolved. The port sites and utility incision have been standardized. We believe this anastomotic technique has several advantages when performing a minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy in comparison with an anastomosis performed by using the EEA device. Since January 2007, our group has performed 77 minimally invasive esophagectomies, of which 31 had an intrathoracic anastomosis using the technique described

Fig 5. The linear is inserted through the anterior port and is articulated. Traction on the stay sutures allows closing the anterior defect.

herein. There was one postoperative leak that required a return to the operating room. A leak occurred at the corner of the anastomosis where the anterior gastrotomy is closed. This was easily repaired and buttressed with an intercostal muscle ap. There were no other anastomotic complications in this group of patients. The linear stapled anastomotic technique described is reliable and very easy to learn. Thoracic surgeons who are learning to perform an MIE with an intrathoracic anastomosis may want to consider this anastomotic technique.

FEATURE ARTICLES Fig 4. A linear side to side anastomosis (4-cm long) is created between the posterior wall of the esophagus and the anterior wall of the stomach.

References

1. Enestyedt CK, Perry KA, Kim C, et al. Trends in the management of esophageal carcinoma based on provider volume: treatment practices of 618 esophageal surgeons. Dis Esophagus 2010;23:136 44. 2. Biere SS, Cuesta MA, van der Peet DL. Minimally invasive esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Minerva Chir 2009;64:12133. 3. Santillan AA, Farma JM, Shah NR, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2008;6:879 84. 4. Carr SR, Luketich JD. Minimally invasive esophagectomy. An update on the options available. Minerva Chir 2008;63:48195. 5. Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, Wilkens EW Jr., et al. Transthoracic esophagectomy: a safe approach to carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;45:137 43.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- INDUCTION OF LABOURDokument51 SeitenINDUCTION OF LABOURDuncan Jackson100% (1)

- Vedda Blood Sugar Remedy Web v2Dokument110 SeitenVedda Blood Sugar Remedy Web v2thilanga100% (2)

- Biochemistry of Cancer: Dr. Salar A. AhmedDokument11 SeitenBiochemistry of Cancer: Dr. Salar A. AhmedJoo Se HyukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laparoscopic Weight Loss Surgery (Bariatric Surgery) : A Simple Guide To Help Answer Your QuestionsDokument67 SeitenLaparoscopic Weight Loss Surgery (Bariatric Surgery) : A Simple Guide To Help Answer Your QuestionsSAGESWebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dancing With The HungerDokument85 SeitenDancing With The HungerJohn McLean100% (1)

- Diseases of Oral CavityDokument60 SeitenDiseases of Oral Cavityfredrick damian80% (5)

- Pediatric Leukemia Resident Education Lecture SeriesDokument42 SeitenPediatric Leukemia Resident Education Lecture SeriesFilbertaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cure For All DiseasesDokument4 SeitenCure For All DiseasesNiquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Activity Sheet QTR1 LC1-9Dokument14 SeitenHealth Activity Sheet QTR1 LC1-9Nota BelzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protein TherapeuticsDokument14 SeitenProtein TherapeuticsSumanth Kumar ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 924154502X Eng HR PDFDokument587 Seiten924154502X Eng HR PDFSnufkin GreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Benefits and Risks of Extended Breastfeeding For Mother and ChildDokument10 SeitenThe Benefits and Risks of Extended Breastfeeding For Mother and Childapi-298797605Noch keine Bewertungen

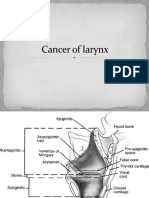

- Cancer of LarynxDokument46 SeitenCancer of LarynxVIDYANoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Signs of The ZodiacDokument9 Seiten12 Signs of The ZodiacProfessorAsim Kumar MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humoral and Cell Mediated ImmunityDokument3 SeitenHumoral and Cell Mediated Immunityinder191Noch keine Bewertungen

- Brokenshire College drug studyDokument1 SeiteBrokenshire College drug studyACOB, Jamil C.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Test Uncovers Asthma Gene DiscoveryDokument20 SeitenReading Test Uncovers Asthma Gene DiscoveryKush Gurung100% (11)

- Male Genitourinary AssessmentDokument46 SeitenMale Genitourinary AssessmentNicole Victorino LigutanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fix DapusDokument6 SeitenFix Dapuseka saptaning windu fitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- MiasmsDokument2 SeitenMiasmsAshu Ashi100% (1)

- Bentonite Trugel 100 2007-09Dokument1 SeiteBentonite Trugel 100 2007-09Tanadol PongsripachaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simplemente RacionalDokument280 SeitenSimplemente RacionalAlfredo Casillas100% (1)

- MSDS Methane PDFDokument8 SeitenMSDS Methane PDFJayusAliRahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- STD Lesson 1Dokument8 SeitenSTD Lesson 1api-277611497Noch keine Bewertungen

- IMAI District Clinician Manual: Hospital Care For Adolescents and AdultsDokument504 SeitenIMAI District Clinician Manual: Hospital Care For Adolescents and AdultsLuis Eduardo LosadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skin Pigmentation + Hari DisorderDokument113 SeitenSkin Pigmentation + Hari DisorderAfiqah So JasmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frozen SectionDokument9 SeitenFrozen SectionBabatunde AjibolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EUROSCOREIIDokument3 SeitenEUROSCOREIIFabiánBejaranoLeónNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cancer Prevention Health Education ProgramDokument9 SeitenCancer Prevention Health Education ProgramKheneille Vaughn Javier GuevarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical PediatricDokument358 SeitenMedical PediatricAishah Alsaud100% (10)