Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Legislation and Regulation Tushnet

Hochgeladen von

Sarah HuffOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Legislation and Regulation Tushnet

Hochgeladen von

Sarah HuffCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

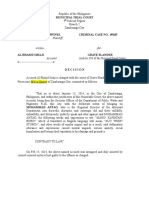

Legislation and Regulation Outline I. Purpose of Regulating Risk A) Introduction: Farwell v.

The Boston and Worcester Railroad Corporation (Shaw opinion) Facts: Farwell worked for the defendant (railroad company). His hand was crushed while he was on duty, because a switchman negligently ran a train off the track. Farwell sued the railroad for the negligence of its employee. Holding: The court held that the defendant was not liable for Farwells injury. Arguments in the opinion: 1. On a railroad, the worker is better positioned than the employer to make the workplace safer. If Farwell sees workers acting dangerously, he can report it, quit, or demand more money. Thus, the employer should not be held liable for the injury. 2. There is an implied contract that the employee bears the risk of injury created by negligence of a fellow servant. Railroad workers have an inherently dangerous profession, but they are fully compensated for the risks of the job in their salaries. If they observe on the job that they are not being fully compensated for risks, they can bargain or quit. If they do not do this, we can assume they are satisfied. 3. There is no precedent to show that the defendant should take responsibility. Analysis of holding: It is arguably unimportant. It doesnt matter if there is liability or no liability for employers such as the Boston and Worcester Railroad Corporation. If there is liability, the risk compensation in an employees salary is eliminated. If there is not liability, the employee can use the risk compensation to buy insurance. Either way, the employee is in the same position. However, this takes into account many assumptions (the employee has perfect information, the employee can adequately assess risks, and the employee is not constrained). In this case, Walters likely has restricted choices. B) Reason for Regulating 1: Lack of information Compensatory wage premiums only succeed when workers have adequate information about the risks they are exposed to. Farwell should bear ordinary risks of job (that he knows about or can observe), but not risks that he is not aware of. If workers are exposed to the risk of developing long-latent disease, they will likely not know about this risk, and they will not be compensated for it. Regulatory response 1: mandate risk disclosure by the employers. Regulatory response 2: fund research regarding the risks, if the employer does not know about the extent of the risks. Criticism of mandatory disclosures #1: Competitor can expose the risks at other firms, and if necessary, a private (or governmental) agency can verify the accuracy of such exposures. It is unnecessary to force companies to disclose information.

Response: Competitors will not always expose the risks. For instance, if the entire industry uses a risky chemical, they will simply want to ignore the risks instead of claiming their product is less risky. Criticism of mandatory disclosures #2: Peoples individual insurance premiums will contain accurate information about the risk of a job/product, thereby solving the lack of information problem. Response: Insurance markets are imperfect, due to problems such as adverse selection. C) Reason for Regulating 2: Poor Risk Appraisal by Individuals Even if workers are given information about risks, they may process the information poorly. They may be cognitively unable to make the right decisions. They may just make bad choices, in societys view. Thus, they may not demand the correct wage premium. For instance, hyperbolic discounting may occur, in which the individual does not value far-future risks adequately. Regulatory response: Since information alone may not be adequate, the correct regulatory response might be to ban the danger. This can be justified by strong paternalistic or weak paternalistic arguments. Strong Paternalism: The government says, We will not allow you to make that choice, even if it is truly your preference. We value the sanctity of human life too much. Weak Paternalism: The government says, We are overriding your immediate preferences because we dont think your choice is consistent with your own risk preferences. You are making poor decisions because of poor information or poor cognitive capacities This can also be justified because society ends up often paying when a person gets sick (negative externality). People are not turned away from emergency rooms, even when they have no insurance. D) Reason for Regulating 3: Constrained Choices Workers do not have options besides taking jobs with inadequate risk premiums. Regulatory Response 1: provide training programs to workers, so their choices are no longer constrained Regulatory Response 2: ban the dangerous job Response 2 may be inappropriate because it would constrain choices even further. The next best job will be even worse for the worker. E) Reason for Regulating 4: Negative Externalities Example: A man sells land to a plant (which will pollute) for $200,000 more than the next highest builder. The neighbors will collectively lose $200,008 from the pollution, so they should pay the man not to sell the land to the plant. However, collective action is difficult, because the

individual neighbors will not be honest about their preferences. Therefore, the man will likely sell the land to the plant. Negative externalities are a problem when the solution necessitates collective action. F) General Criticisms of Regulation We are paternalistic because we are squeamish about living in a world with too much cancer. This is selfish because it is disregarding individual preferences (they may prefer a richer, shorter life). Rose-Ackerman Government programs and policies often fail. Thus, it may not be beneficial to keep the government in charge of risk regulation. G) Readings 1. Margaret Radin- Discussing Market Inalienability and Double Bind Problem Inalienability: Should you be able to sell your pinking? Should anything be inalienable? Should you have an inalienable right to clean drinking water? Radin says some rights are inalienable, depending on their essentiality. Double bind problem: When you pose a regulation, you must think about the cost to the regulated party (for instance, forcing women not to participate in prostitution). On the one hand, prohibiting prostitution takes away an economic opportunity from women. On the other hand, allowing prostitution turns women into commodities, which may lead to gender oppression. The double bind problem is related to constrained choices. Radin says there is no principled solution to the double bind. 2. Robert Steinfeld (quoting Robert Hale)- Discussing Unequal Bargaining Power Unequal bargaining power has a pervasive effect on legal regulation. For instance, the bargaining power of Walters and Moeves are uneven. If you need $100 dollars, and would make $125 in a safe job and $75 in an unsafe job, you will take the unsafe job. However, if you have $50 of wealth, you will take the safe job. Constrained choices lead to unequal bargaining power. Possible regulatory response: Equalize bargaining power. Hale: Everyone agrees it is impermissible to force someone physically to enter into a contract. From the point of view of the employee, there is no difference between physical and economic coercion. You cant starve. Economic coercion arises from distribution of legal rights. For instance, you only steel bread because you are not legally entitled to it. Distribution of legal rights makes some peoples choices so narrow that they need to decide between the undesirable contract and starving. If employees had entitlement to jobs with appropriate safety standards, they would have much more bargaining power.

3. Duncan Kennedy- Discussing Justifications for Regulation For each type of regulation, there are formally adequate justifications based on efficiency, distributional, and paternalistic arguments. Empirical judgments are necessary for full justification (facts) All studies are flawed by the terms of the researcher. Contradictory empirical arguments can always be made. Your ideology dictates whether or not you accept a formally adequate argument with thin empirical evidence. Preference ranking of justifications in public discourse: 1) Efficiency; 2) Distributive; 3) Paternalistic. This preference ranking is ideological. There is nothing inherently wrong with paternalistic arguments, and it is the real justification behind a lot of regulation. Now, we are less afraid to use paternalistic arguments. Efficiency Argument: There are market failures due to lack of information and cognitive imperfection, so you should regulate to improve the efficient operation of the market. This involves a lot of information distribution regulation (making sure employees and consumers understand risks). Due to cognitive processing problems, it also involves banning certain dangers. People in their capacity as voters know more than people in their capacity as consumers, since they are not affected by certain cognitive biases. Consumers have trouble making trade offs between products with complex sets of characteristics. In addition, consumers do not always consider long-term risks. Thus, perhaps government knows better than individual consumers. Another efficiency argument: negative externality arguments (regulate risk so that the party creating the risk internalizes it). Efficiency justifications require empirical arguments. They only make sense if you say that the market is inherently inefficient. Distributive Argument: Regulations should shift wealth so we are no longer worried that people will make constrained choices due to unequal bargaining power. This includes compulsory terms: the wealthier class should be forced to do certain things to improve the situation of the poorer class even if the poorer class could not bargain for it themselves due to uneven bargaining power. Problem: Landlord will raise the rent problem. If you force the landlord to maintain a high level of quality, he may raise the rent, and tenants will be pushed out of the market. Their choices will become even more constrained. Thus, maybe regulation is not a good tool to transfer wealth. Maybe the tax structure should be changed. However, for political reasons, it might be more difficult to achieve tax redistribution than regulation.

Even if regulation is not the best way to redistribute wealth, it is successful in certain circumstances. In these circumstances, compulsory terms can be imposed in a market scenario with the effect of transferring power from the party with more bargaining power to the party with less bargaining power: Circumstance 1: A regulation says that an apartment must be qualitatively improved, and that rents charged to current tenants cannot be increased due to their contract. The tenants in place get benefits from both the quality improvement and rent freeze. However, future tenants do not (their rents will be raised). Circumstance 2: A law says that an employer will be liable for sexual harassment on the job. In this case, the employer can comply with the regulation without any effect on their costs. Circumstance 3: A company periodically redesigns their products. In the course of their redesign, you force them to make safety improvements. The company must incur costs of redesign anyways, and there is always some sloppiness in manufacturing. At the moment of redesign, you force them to squeeze out inefficiency. Circumstance 4: A significant portion of the consumers do not care much about the good, and if the price goes up, they will buy something else. In addition, the sellers are competitive, and they have a large fixed investment in what they sell. Thus, sellers cannot increase the goods price after regulation, and the buyers will benefit from an increased quality and a stable price. However, this is only a short term effect (the sellers will eventually get out of the market). According to Tushnet, these circumstances rarely occur. However, if they do, you can argue that regulation is good because it overcomes differences in bargaining power. Paternalistic Argument: Some choices are just bad choices. Voters get a psychological benefit from living in a society where people cannot make stupid decisions. We are getting more comfortable with paternalistic arguments. We already accept paternalism in our personal lives (making decisions for our dying relatives). In comments section (Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler): There is a very weak form of paternalism known as libertarian paternalism. In this formulation, you do not block individual choices, but rather attempt to shift peoples choices. For instance, you could put healthier foods at the beginning of the cafeteria line. 5. Kip Viscusi- Discussing Potential Problems with Paternalism Wealthier people value safety more than poorer people. Since the individuals controlling government policy tend to be richer than average, their preferences may deviate from the country. This raises an ethical issue. In addition, wealthier nations (like the U.S.) value safety more than poorer nations. Should the US ban exports of products banned in US? Should the US allow import of products made under unsatisfactory conditions (according to US standards)? It seems inappropriate to extend our paternalism to other countries. Perhaps we can justify protectionist policies with economic arguments.

II. Regulatory Institution 1: The Courts A. Ivey Memorandum (1973) This is a document written by a General Motors engineer, evaluating the risk of placing gas tanks in a certain position. In GM automobiles, the fuel tank is positioned so that predictable fuel tank explosions occur. Ivey was asked to figure out the cost to GM of: 1) producing the same cars and facing liability; and 2) redesigning the car and reducing liability. Ivey concludes that it would be worth $2.20 per automobile to prevent fuel fires by redesigning them. Other internal documents show it would cost at least $8.59 per automobile to implement the redesign. Thus, it would not be cost-effective to save lives. Could GM be prosecuted for murdering someone who dies due to a fuel tank explosion, if they do not redesign the cars? Under California Penal Code section 187-188: Murder is the unlawful killing of a human beingwith malice aforethought that shows an abandoned and malignant heart. How can a corporation have an abandoned and malignant heart? Also, they were not deliberately trying to kill anyone (though they did deliberately fail to redesign the cars). However, under the British Corporate Manslaughter/Homicide Statute, they might be held liable. Under the statute, it is an offence to run/manage an organization in a way that causes a persons death and amounts to breech of relevant duty of care. B. Ayers v. Township of Jackson The township operated a landfill. Pollutants leaked into the municipal water supply, due to negligent conduct. The township eventually told the residents about the leak, and told them to retrieve their own water (through barrels). Their quality of life was lowered due to this inconvenience (the court held the township was liable for this). The residents made another claim: They claimed that the township was responsible for exposing them to risk of future illness. (Note: no one claimed they were experiencing current illness.) The court holds that the township is not liable for enhanced risk for future disease. Why cant they just sue when they get sick later? 1) Statute of limitations; 2) hard to show causation The court, however, says that the statute of limitations will not be a problem. You can interpret it to begin running when the causal connection between the illness and polluted water is discovered. The court also says that the legislature can relax the causation standard. The dissent says that enhanced risk is an injury in itself. C. Lon Fuller (p. 192)- Discussing Limits of Adjudication

Bipolar v. Polycentric Disputes Bipolar: 2 parties, narrowly confined resolution, claim of right is based on a principle Polycentric: Web-like relationship between aspects of the case (tug one string, and there are effects far away), there are many parties, the dispute is based on welfare or equity (unprincipled), the results can be unexpected Example of a polycentric dispute: Paintings need to be split up in equal shares. When one party gets one painting, it complicates how other paintings should be allocated. Courts are not good at resolving polycentric disputes. On the other hand, the legislative branch can resolve polycentric disputes. When courts try to resolve polycentric disputes, bad things happen: 1) The court makes the right decision, but fails in implementing a remedy because they do not have the tools 2) Judges will be tempted to perform functions outside their role, such as consulting parties and trying out solutions (***however, today judges do step outside their role, which is why they do sometimes solve polycentric disputes); 3) the problem will be reformulated so it can be solved. Extra class discussion, not in article: Ayers is a polycentric dispute. Although the claim itself is based on principle, the resolution cannot be based on principle. The court does not recognize a claim for enhanced risk because in order to do so, it would need to develop a complex workers compensation program as a remedy. This is not something a court can easily do. Although Farwell may be considered to be a polycentric dispute since it creates important precedent, the court did not know this at the time. Thus, it is essentially bipolar (no case can be purely bipolar in the common law system). III. Regulatory Institution 2: The Legislature The legislature is more apt at solving polycentric disputes than courts. The legislature can either create specific, targeted statutes or create an agency and delegate regulation responsibilities. Characteristics of the Legislature: 1) Unprincipled The legislature does not need a principled basis for its decisions, unlike courts (Fuller). Thus, it can ban one dangerous chemical but not another. 2) Responds to electoral incentives Due to electoral incentives, the legislature may delegate regulation responsibilities to agencies. This allows the legislature to act like it is accomplishing something, without political risk. 3) Generalists For instance, the Senate passes a bail out plan and a text messaging ban for drivers on the same day IV. Regulatory Institution 3: The Agency

Characteristics of agency: 1) Experts in their specialized fields 2) Unique incentives As professionals, they have the incentive to provide solutions that satisfy their communities of professionals (the FDA tries to appease other scientists). In addition, however, they are subject to indirect political control. How agencies are created: The legislature passes a statute to create an agency. The president decides who the head of the agency will be. However, there are not political incentives for each individual decision the agency makes. The legislature can exert indirect political control over specific agency decisions, but they can only exert informal control. They can exert control by: 1) Controlling the agencys budget (money requests will be scrutinized more closely if the agency acts against the legislatures wishes). 2) Oversight hearings (normally this just disturbs agencies. Only influential members of Congress are important in these hearings). There are two types of agencies: independent agencies and executive branch agencies There are only a small number of independent agencies. In independent agencies, the leaders are appointed for terms longer than four years and have protection against removal. Most agencies are located in the executive branch (like the FDA). Thus, the president can remove the agencys head for any reason. IV. Regulatory Institution Comparisons A. Clayton Gillette and James Krier (p. 205) - Comparing Court and Agency Risk Regulation Both agencies and courts can regulate risks (this article does not deal with the legislature). Agencies regulate risks directly, while courts regulate risks be forcing parties to internalize externalities. Both institutions are biased by access bias and process bias. You only want to figure out which institution is less biased in a certain scenario. Access Bias: In courts, the incentive for an individual to sue for a public risk is low, since the risk is widely distributed. In addition, costs of litigation are higher than individual recovery. This problem can be addressed by class action lawsuits and contingency fees for lawyers.

However, entrepreneurial lawyers have incentives to settle non-optimally (since litigation is very costly). In agencies, there is also access bias. Agencies are self-starting, but their priorities might be skewed. The agency must figure out its own priorities. These priorities will be decided by the attention issues get, and not their actual social impact. There will be action when there is political pressure, such as interest group mobilization. Interest group positions do not necessarily correlate with scientific evidence or agency expertise. This is called agency capture. In theory, agencies are self-starting, but they wont regulate against an industry if they are captured by the industry. Industry capture often occurs, especially in extremely specialized agencies (which only deal with one industry). The agency head is a political appointee. The industry is often able to influence the President regarding who the head of the agency should be. In addition, the agency may be staffed by members of the industry. Lastly, the industry can argue that more regulation will lead to a shrinking industry, and thus less work for the agencies. Alternatively, an NGO can capture an industry, leading to over regulation. While this article does not discuss the legislature, there is also access bias in the legislature. In order to be heard, you must bring money or votes. An NGO can say, We dont have money, but we can bring you votes. The industry can say, We cant give you votes, but we can give you campaign contributions. Process Bias: Agencies: Process bias arises out of agency expertise. If you are an engineer, for instance, you will look for engineering solutions to a problem. In order to prevent accidents, you will look into car manufacturing instead of drivers education. Courts: Courts are rule of law oriented. This affects the causes of actions and remedies that courts will recognize. For example, there is process bias in Ayers: the court will not recognize a claim for enhanced risk, because the remedy could not be based on principle. In addition, courts often prefer rules over standards, since rule-based decisions are in line with rule of law values (though top judges know that rules and standards are equally valid). Thus, we may use rules that would be better expressed as standards (statute of limitations). Lastly, courts have a general bias for law-based solutions, rather than settlements and alternative dispute resolution. Sometimes there is tension between process bias and access bias. The article argues that courts are pulled in opposite directions by process and access bias. Courts tend to be pro-victim on process bias and anti-victim on access bias (Tushnet finds this argument questionable, however). So, is bias worse in agencies or courts? The article says that it is a close call, even though most scholars (such as Fuller) say that agencies are better than courts. In general, Gillette and Krier are sympathetic to court regulation. Perhaps we could use courts and agencies (and the legislature) in complementary ways. For instance, suppose that for issue type 1, there is pro-victim access bias in courts but anti-victim access bias in agencies. For issue type 2, it is opposite. If you think there is too much or too little regulation, you can use different institutions for different issues.

B. William Felstiner, Richard Abel, and Austin Sarat (p. 231) Discussing Court Access Bias There are three steps in making a claim in court: Naming, Blaming, and Claiming. Naming: Having a PIE (Perceived injurious experience), and recognizing that something is wrong. It is possible not to recognize an injurious experience. Blaiming: Something is wrong with my life, and someone is causing it. Claiming: Something is wrong with my life, someone is causing it, and I want that person to pay attention and compensate me. Moving from one stage to the next is complicated. Barrier to claiming: costs, embarrassment, apologies Barrier to blaming: pity The role of the lawyer: induce people to move through the stages (personal injury lawyer advertisements). Take away point: Claiming behavior is a product of institutional design. Institutions help create blaming and claiming behavior. You can adjust institutions to end up with the proper amount of blaming and claiming. C. Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife (p. 264) Does the Endangered Species Act pertain to activities outside of the United States? The US government provided finances to build the Aswan High Dam on the Nile. This will harm an endangered species (crocodiles). If the army corps constructs a dam in the US that might lead to the extinction of an endangered species, they must take steps to mitigate damages (consult with the Secretary of the Interior). However, the Interior Department says that there is no consultation requirement for activities outside the US. The plaintiff sues the Secretary of Interior regarding this rule. The plaintiffs are women who saw endangered species in other countries, including the Nile crocodile. They plan to return to see the Crocodiles. The court held that the women did not have standing to bring this claim. They were not directly harmed by the building of the Aswan Dam. There is a three part test for standing: 1) Injury in fact (actual and imminent, not just hypothetical) 2) Causal connection 3) Redressability (Likelihood that there will be a favorable outcome) In this case, the alleged injury is the lack of future enjoyment in seeing the crocodiles. However, the injury is speculative, and not imminent. They did not have plane tickets to go to Egypt. If they did have plane tickets, they might have standing.

10

The plaintiffs made additional arguments: 1) Vocational nexus: I work with the Nile crocodile in the zoo. If it goes extinct, I will lose my work. This argument is problematic, because it goes too far and would give too many people standing. 2) Procedural injury: According to the citizen suit provision in the ESA, anyone can file suit to force an injunction on an agency violating the ESA. The statute says that anyone can sue if the executive does not properly execute the law. Thus, the plaintiffs suffered injury because they enjoy rule of law. This argument is also problematic. Should the courts really determine how the executive branch should execute the law? What about separation of power? Pros of court oversight of the executive branch: Courts are low cost institutions. Anyone can go to court. In addition, a court must take the case (as long as there is standing, etc.) Cons of court oversight of the executive branch: Judges should not make policy decisions, because they are not elected. In addition, priorities may not be set right if the courts get involved, because courts cannot tell people to go away. Pros of legislature oversight of the executive branch: It can set its own priorities. Cons of legislature oversight of the executive branch: It may be unduly influenced by political pressure. In addition, it is expensive to be heard by Congress. If you have no money, you will probably be ignored. Scalia: Complaints about executive non-compliance with the law should be addressed to Congress, not courts. This was how our system was set up at the institutional design state. There are pros and cons to both systems. V. Statutory Interpretation A. Introduction There are two contexts in which statutory interpretation occurs. Sometimes, the statute from the legislature is presented directly to court. Other times, the legislature creates a statute, the agency interprets it, and the agencys interpretation is presented to court. There are three general methods of interpreting statutes: intentionalism, purposivism, and textualism. All approaches are acceptable. Intentionalism: Courts figure out what the legislature had in mind when they formed the legislation. They ask, if the legislature was presented with this problem, what would they do? In order to do this, they look towards legislative history. Critique of intentionalism: The materials that intentionalists rely on do not provide adequate information. In addition, it is hard to find the intention of a multi-member body. Purposivism: Courts assume that the legislature is a reasonable body pursuing reasonable goals reasonably. They do not necessarily try to get into the legislatures head. Rather, they assume the legislature is rational, and thereby try to figure out the statutes purpose. They use both legislative history and common sense.

11

Critique of purposivism: The legislature is not reasonable. It is just a body of politicians trying to get reelected. In addition, statutes do not have purposes, they are just deals. In addition, purposivism gives a lot of judicial discretion, since each judge has a unique view about what is reasonable. Advantage of purposivism: You can adapt the statute to the current time and issues, since you are just looking for the overarching purpose of the statute. Textualism: Courts use the language of the statute to interpret it. They use the dictionary to determine the meaning of individual words. In addition, if the meaning of a word is unclear, they interpret it in light of the words that came before it. In general, courts first look for the most common meaning of a word, and then look for the meaning of the word in context. Critique of textualism: It can lead to socially undesirable results, which are at odds with what reasonable people would do. In addition, textualism has a libertarian tilt, and there is no reason to adapt that specific tilt. B. Karl Llewellyn (p. 319) Discussing Grand Style vs. Formal Style Reasoning This article contains a list of different canons of interpretation. For every canon pointing in one direction, there is another canon pointing in the other direction. All law is simply 30ish moves (different modes of reasoning). Learning law= learning the moves. There are equally correct solutions to dealing with statutes and precedent. Llewellyn discusses grand style and formal style reasoning: Grand Style: Judges using the grand style want wisdom in the results, and they want the law to make sense for all of us. In order to produce wise results, the judge is pushed to focus on the facts of the case. This is ok, but we dont want to produce justice only for this particular case. Instead, the judge must view the case as an example of a recurring situation type. If the judge resolves the situation type correctly, the law will be reasonable for everyone, since everyone could be in that situation. It is up to the judge to decide which situation type the case fits into. This is a matter of judgment. We hope the judge gets it right so the law makes sense for everyone. Grand style reasoning fits with purposivism, assuming that the legislature is a rational body pursuing reasonable goals reasonably. The judge says, What would a reasonable legislature do to pursue reasonable goals in a reasonable manner? Well, I am reasonable, so what would I do? Grand style judges must exercise their own judgment extensively. This can be good, but it can be dangerous (what if they have bad judgment?) Grand style judges also use legislative history (or any other useful information) to figure out a reasonable goal. Formal Style: Judges using the formal style are nervous about exercising their own judgment. They do not ask what is best for society, but rather utilize the text explicitly. This fits with the textualist approach. Formal style judges do not use legislative history or their own creativity/sense. Certain periods of history have either grand style or formal style reasoning tendencies. Right now, nervous grand style reasoning prevails. In addition, certain types of judges are inclined to

12

use grand style vs. formal style reasoning. If a judge is not confident about the quality of his own judgment, he will tend to use formal style reasoning. In addition, risk adverse judges tend to use formal style reasoning, while creative judges tend to use grand style reasoning. Other reasons for using formal style reasoning (despite outcomes possibly bad for society: lack of confidence in successors, lower court judges, and his future self). C. Stephen Breyer (p. 339) Discussing Situations in Which Legislative History Should Be Considered (Intentionalism/Purposivism) According to Breyer, judges should rely on legislative history when it helps them understand the statutes purpose. (Note: this mixes together intentionalism and purposivism). Breyer recognizes that bills sponsors do not write statutes themselves, and a lot of people are involved. Thus, floor statements and committee reports do not represent the pure intention of the sponsors. However, the floor statements and reports do represent the expertise of the involved parties. In addition, groups involved in the legislative process expect that courts will rely on floor statements/reports. This is pro-democracy, and if they didnt expect this, the process of law making would be different. Breyer also recognizes that a lot of legislation is just the result of interest-group deals. Thus, they might not be directed to a broad social goal. However, we still need to uphold the deals. If we ignore them, we would be imagining political forces at the time, according to our own ideologies. Under what circumstances should judges rely on legislative history? Broadly, he says we should rely on history when it helps us understand the statutes purpose. He also discusses more specific situations. (For each of the circumstances, he provides a specific example) 1) Avoiding absurd results 2) Potential drafting error 3) Looking for specific meaning of words (first look at common meaning, then look for technical, specialized meaning) 4) Identifying a reasonable purpose for the statute 5) Choosing among reasonable interpretations of a politically controversial statute D. Frank Easterbrook (p. 328) - A Defense of Textualism Easterbrook is a textualist. He believes that a statute should not be applied to a certain circumstance unless the statute specifically and unambiguously applies to the circumstance, and unless the legislature delegated interpretation of the statute to the court, the statute should not be applied. Under his approach, a lot of the analytic work seeks to find out whether there was delegation to the courts. Easterbrook believes in a punitive approach to statutory interpretation: unless the legislature makes the statute clear, the court should strike down the entire statute. This forces the legislature to be specific, and punishes sloppiness. Easterbrook gives four main reasons why legislative history should not be considered 1) Legislatures are multi-member parties, and thus they dont have intent 2) Gap filling construction has the same effects as extending the terms of the legislature and allowing that legislature to avoid submitting its plan to the executive for veto.

13

3) A principle that statutes are inapplicable unless they either plainly supply a rule of decision or delegate the power to create such a rule is consistent with the liberal principles underlying our political order. Basically, private agreements, not the government, should control most aspects of our lives. We should therefore not extend the power of statutes. 4) Statutory interpretation is difficult, and most judges do not have the skill set to perform creative interpretation properly. E. Church of the Holy Trinity v. US (p. 351)- Brewer uses an intentionalist/purposivist approach A statute does not allow organizations to encourage the migration of foreigners. Does this statute apply to a church encouraging the migration of its pastor? The court says that the statute does not apply because: 1) The statutes tile only includes the word labor (which commonly means manual labor); 2) The reasonable purpose of the statute was to keep out manual labor; 3) a committee thought of writing manual labor instead of labor, but they decided it would be assumed; 4) it is a Christian nation, and there is no reason to keep out pastors. People involved in the legislative process expect committee reports and statements to be given meaning. F. USA v Marshall (p. 356) - Easterbrook Uses a Textualist Approach, Posner (Dissent) Uses a Purposivist Approach Question: whether a statute which set mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment- five years for selling more than one gram of a mixture or substance containing a detectable amount of LSD, ten years for more than 10 grams- excludes the weight of a carrier medium Holding: the statute does not exclude the weight of a carrier meaning. There is only one reasonable way to interpret the statute (the weight of the carrier meaning is included). Dissent first argument: Interpreting the statute this way is unconstitutional. It would prevent giving everyone equal protection of the law (due process). Easterbrook counterargument: it is not unconstitutional. Canon of construction: construe statutes so they do not conflict with the Constitution. Modern version of canon: if there is a possibly unconstitutional way to interpret a statute, you should just interpret the statute the other way. The dissent uses this approach. Problem: this allows courts to impose their own interpretation without actually deciding if the other interpretation is constitutional. Dissent second argument: Paper is a carrier medium (like a bottle), and not part of the mixture. Easterbrook counterargument: paper is definitely part of the mixture, this is a bad analogy (you would never say a bottle is mixed with alcohol) Dissent third argument: We want a sensible policy result, so we should look for a reasonable interpretation that does not give an absurd result. Easterbrook counterargument: We shouldnt care about this. The statute only has one coherent meaning, and as long as it is constitutional, we should use it. G. Chickasaw Nation v. US (Breyer, p. 369) Weighing Canons of Interpretation

14

There is a contradictory statute, so there must be a drafting error. Relevant statute in Indian Gaming Regulatory Act: The provisions of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986] (includingchapter 35 of such Code) concerning the reporting and withholding of taxes with respect to the winnings from gamingshall apply to Indian gaming operationsin the same manner as such provisions apply to State gaming and wagering options. Problem: Chapter 35 deals with imposing a tax, not reporting/withholding taxes. Breyer: it looks like the inclusion of Chapter 35 in the parenthetical was a mistake. This statute was never referred to the finance committee (which is tax knowledgeable). The reference to Chapter 35 should have been excised when the statute was revised, but it wasnt. Also, there is a Pro-Indian Canon of Interpretation. You should interpret statutes in favor of Indians when there is ambiguity. Problem: competing canons of interpretation Competing canons: 1) Anti tax exemption canon of interpretation; 2) words should not be interpreted as unimportant, if possible. Canons provide interpretive moves that judges can use to get results that make sense for all of us. This case creates a problem for textualist, since there is clearly contradictory language. Thus, maybe you have to resort to the grand style, and use canons to help you interpret the statute. Easterbrook would take a different approach. He believes that you should disregard a statute if there is contradictory language. In this case, however, if you disregard the statute, are taxes imposed or not? Usually, the party relying on the statute shouldnt prevail. But here, who is relying on the statute? H. Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council (Stevens, p. 379) Interpreting Statutes Which an Agency Already Interpreted Introduction: The duty of the court is to interpret the law. Sometimes, courts interpret legislative statutes directly. Other times, agencies must interpret statutes first. In the second case, what is the courts role? To answer this, we first must consider the characteristics of the branches of government. Legislature: generalist, politically accountable Courts: generalists, rule of law oriented, politically independent Agencies: specialists, indirectly politically accountable (accountable to the president, and thus indirectly accountable to the people) Facts of case: Statute: In non-attainment States, you must get permits to modify stationary sources of pollution if the modifications increase pollution emissions. Question: can a plant change internal emissions without a permit, and thereby increase the emissions from certain buildings, if overall emissions dont increase?

15

Chevron wants to use a bubble concept. They want to modify something in building 1 that will lead to lower air quality. However, they will modify building 3 so that, as a whole, the modifications improve air quality. Thus, they argue they shouldnt need a permit. The EPA agrees with this interpretation, and allows it. History: the EPA originally rejected the bubble concept, but then adopted it. This happened when Reagan was elected. The EPA changed its interpretation to be more manufacture friendly Policy reasons for the bubble concept: 1) You do not want to retard progression. If you cant modify building one (creating more pollution), you may not be able to afford modifying building two (causing an overall decrease in pollution). 2) All that matters is overall output of pollution Policy reason against the bubble concept: we want to induce technology (look for technology which will reduce emissions) Main question: What is the definition of a stationary source? Every component of a plant, or the plant as a whole? Court of Appeals: The bubble concept would only make sense if the rule was designed to maintain, rather than enhance, air quality. However, we are talking about a rule pertaining to non-attainment zones, and thus the rules goal is to increase air quality. Thus, we reject the bubble concept. Supreme Court: We can apply the bubble concept. Stationary source has a flexible definition, and thus it can be left to the agency. An agency has expertise- so it may know the best way to deal with pollution (BUT it has no advantage with respect to interpreting what Congress wrote). The Supreme Court basically said that it is acceptable for statutory interpretation to change in response to a change in administration (agencies are indirectly politically accountable, not just experts). Method of Statutory Interpretation Developed in Chevron: Chevron Step 1: Is the statute ambiguous? If statutes are unambiguous, no interpretation is needed. It must be interpreted according to its clear meaning. If the statute is ambiguous, you must move on to Step 0. Note: Congress should clearly resolve issues when they are dealing with a big issue; and when a deal is struck between interest groups Chevron Step 0: Did the legislature delegate interpretive responsibility to the court of to an agency? More specifically, did the Congress delegate authority to speak with the force of law? (US v. Mead Corp) If it delegated responsibility to the court, the court should interpret the statute. If it delegated responsibility to the agency, you must move on to Step 2. Note: Step 0 is often difficult to figure out

16

How to figure out if there was delegation to the agency: 1) the statute itself (did Congress explicitly or implicitly leave a gap that needs to be filled?); 2) the formality of the agencys procedures (legislature and courts are more comfortable with agency interpretation when they use a formal process. It is expensive for an agency to act formally. If they take this expense, it signals they have been given authority. An example of formality is the notice-and-comment rule making procedure). United States v. Mead Corp: to determine whether authority was delegated to agency, look at how formally the agency acted. Note: Under this rule, it is much very unclear if statutory interpretation is delegated to agencies. Thus, courts can say that there is delegation less often, and do not need to defer to agencies as much. Skidmore v Swift & Co: listen to an agency in proportion to its persuasiveness (like any other evidence, dicta) When do you want courts to interpret statutes independently? Answer: When you want to take advantage of generalists with no political accountability. When no expertise is necessary (minor details), and when you dont care about political responsibility (or dont want statutory interpretation to change with change in administration, like in Chevron) In addition, with agencies, there is a slippage problem. An administration can have two agendas, but the public only likes one agenda. An agency can exercise an agenda people dont like. So this weakens the argument that agencies are very politically accountable. Chevron Step 2: Was the agencys interpretation reasonable? If it was, you should use the agencys interpretation. If not, the court should interpret the statute independently. It is extremely rare to say that the agency has not been rational. If a decision looks outrageous, you would just say that Congress resolved the issue clearly (step 1) Note: a textualist is likely to stop at step 1. If the issue isnt resolved clearly by the Congress, the statute should not apply. I. Food & Drug Administration v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp (OConnor, p. 388) Chevron Analysis in Action Statutory issue: Does Tobacco fall under the definition of Drug or Device (and thus fall under FDA control, according to the FDCA)? The FDA says it does Drugs and Devices: intended to affect the structure or function of the body FDA says that nicotine is a drug, and that cigarettes are devices This is clearly a reasonable interpretation of the language. Thus, if you find that FDA was given the authority to interpret the state, there is no case This is a Step 1 case: the parties are arguing whether Congress has clearly resolved the issue in the other direction

17

Courts holding: Cigarettes should not be considered drug or devices, and thus should not be regulated by the FDA Court argument 1: You must look at the statute as a whole. The FDA is obligated to ban unsafe, misbranded drugs or devices unless there is an overwhelming benefit. Thus, if cigarettes were considered drugs or devices, they would need to be banned. Legislative history after statute shows they did not intend the FDA to control tobacco (the Congress is controlling tobacco itself). Dissent: A ban of cigarettes would be even more harmful than allowing them (black market). Thus, the agency can regulate cigarettes but still use their discretion to not ban them. Court argument 2: Every prior FDA administrator said that cigarettes are not devices. We are required to do what Congress wanted, and we do not want this to change when the President changes Court argument 3: Under Chevron, when there is a statutory gap in a statute an agency is supposed to implement, implicit authority to fill the gap is given to the agency in question. However, this is not an ordinary case. Congress would not want to give authority to the agency in such a cryptic fashion, given the importance and breadth of the tobacco industry. Thus, Congress must have clearly addressed the issue (Step 1). Congress would want to assume responsibility for such a big issue that they are politically accountable for. Counterargument: The Tobacco industry acts as a special interest in Congress and keeps regulatory bills from being passed. So, it is conceivable that the majority of Congress would want the FDA to regulate tobacco since they dont have this problem (?) and are still politically accountable. In addition, FDA has expertise. J. Massachusetts v. EPA (Supplemental) - Standing Issue and Chevron Anaylsis Cont. Massachusetts (and other states and groups) sues EPA for failing to regulate tailpipe emissions of greenhouse gases Why does Massachusetts have standing? To have standing, you must show injury, causation, and redressability Injury to Massachusetts: loss of coastal property due to sea level rises (state owns shoreline property) Causation: EPA does not regulate properly, and this has some effect on the loss of shoreline. Small, incremental effects should not be discounted (dissent: this is an insignificant effect) Redressability: if EPA was forced to regulate, it would have some beneficial effect. It would be a step in the right direction *The concept of standing has expanded. It allows more judicial oversight, and more participants in the system. Denial of standing is the exception. Merits of Case- Chevron Analysis: Statutory language- EPA should regulate any air pollution from cars which cause problems.air pollutants are air polluting agents includingchemical, physical substances admitted into ambient air

18

Under this statute, does the EPA need to regulate greenhouse gases? Courts holding: Greenhouse gases are air pollutants, and EPA must regulate. EPA Argument 1: Greenhouse gases are not air pollutants, so we do not need to regulate Courts reasoning: Green house gases clearly fit into the definition of air pollutants. The statute is unambiguous (Chevron step 1). Dissent: Greenhouse gases are not air pollutants. If the majoritys definition were correct, there would be absurd results (Frisbees coming from cars would be considered air pollution). EPA Argument 2: Brown v Williamson argument- Additional legislation after statute indicates that the Congress did not think the EPA should regulate Greenhouse gas emissions. Congress is regulating global warming itself. Court response: The legislative statutes are still compatible with EPA having jurisdiction over C02 (EPA regulation would be supplemental to Congress regulation) EPA Argument 3: Brown v Williamson argument- Global warming is a huge deal. We cant believe that Congress wanted to authorize EPA to regulate it through such cryptic language. Court Response: In Brown v Williamson, the tobacco industry would be shut down. This case is different. The auto industry would not need to shut down. They would only need to lower tail pipe emissions. It is not crazy that Congress wanted this result. EPA Argument 4: Even if we have jurisdiction, we do not have to regulate it if doing so is unwise. For instance, we can utilize judgment about whether greenhouse gases can reasonably be expected to endanger public health and welfare. Thus, we do have some discretion. Court Response: True, but EPA cannot make any argument they want. For instance, they cant make broad policy arguments. In addition, they are still vulnerable to Chevron Step 2. Dissent Response: EPA can use broad policy judgments about whether to defer decision about whether to regulate. VI. Administrative Law A. Development of Administrative Law (Discussed by Richard Stewart, p. 416) Administrative law began in the late 19th century. State Legislatures and Congress created agencies to regulate railroad rates. Railroads were quasimonopolistic, so they could overcharge shippers. In addition, agencies were created to implement worker compensation programs. At the beginning, courts were suspicious of agencies, for the following reasons: 1) Agencies interfere with private autonomy/contracting. Monopolies could be attacked via common law. We dont want rate-setting agencies.

19

2) There was a sense that administrative agencies were making arbitrary decisions inconsistent with the rule of law. For instance, in workers compensation programs, workers were compensated for the loss of a hand, even if the employer did not show negligence. The rule of law can be satisfied by general rules adopted by the legislature, or by individualized court application. Problem: agencies fit in the middle. They deal with case-specific application, but they are not courts. Response to concerns: 1) Courts say that agencies are ok, but they must only be given limited discretion. They must be guided (non delegation doctrine). 2) Courts say that agencies can address rule-of-law concerns if they adopt court-like procedures. They must have hearings before deciding a railroad rate. 3) Courts eventually decided that when agencies used expert judgment, this could replace court proceedings or strict legislative guidance. Economists, for instance, can tell them the correct rate to charge. Benefits of Agencies: Expertise, Politically Accountable Progressives in the 20th century argue for greater agency discretion. This is because agencies have expertise AND a sense that legislation could no longer adequately deal with social problems. Reasons Congress no longer seems adequate to create rules: 1) Problems increasingly become technical and the legislature is generalist 2) The pace of change is so rapid that the legislature cannot respond in a timely manner 3) Legislature is corrupt. It is bought be corporations, and thus it is not good at generating policy. Agencies are supposed to be professionals and neutral. By the 1920s, courts are comfortable with administrative agencies. They put up with some deviation from court-like procedures. However, real change happens after the New Deal. At this time, progressives take over. Many agencies form and intervene in controversial ways. The ABA responds by challenging administrative agencies on the ground that they are overly bureaucratic. Walter-Logan bill- Would have restricted agencies by aggressive judicial review of decisions. This is vetoed. Roosevelt, however, knew something needed to be done. Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 (APA)-

20

5 U.S.C. Section 553 (rule making): It describes rule making procedure that agencies must follow. Basically, agencies must give notice of rule making, and give relevant parties a chance to participate. In addition, agencies must give statements of reasoning with rules. 5. U.S.C. Section 706 (scope of review): It gives agencies deference wto rule-making. However, courts can say that an agencies actions are arbitrary and capricious and not supported by evidence. To generalize: Agencies must have hearings, but the hearings do not need to be completely judicial. In addition, limited judicial review is permitted. 1960s and 1970s- Agency capture is noticed. People start to realize that agencies are not just using expertise, but rather weighing interests. Agencies are political in nature. Regulated industries have a lot of access to agencies. They can get allies appointed to agencies, and they have more resources to develop technical arguments. Solution: Improve political process (progressives would say that we should make sure experts are in control. However, since agencies are naturally political, we must change the politics). Ways to improve the political process: 1) Make industry capture harder by making agencies with widespread jurisdiction (not limited to particular industries) 2) Expansion of access to the agency process by beneficiaries of regulation (expansion of standing) 3) Reagan introduces deregulation era (give heads of agencies a larger say; shift decision making authority away from agencies and into Presidents office) Now: these moves are not very helpful in getting rid of agency difficulties. The New Deal structure is so entrenched that you cant get rid of it. Deregulation did have an effect. However, agencies did not stop regulating. Their process just hardened so that they couldnt regulate or deregulate as easily. Later material in the course discusses efforts to create regulatory designs that can overcome regulatory ossification). What else leads to ossification of agencies? By expanding access to the process in the 60s, the process became more cumbersome. Agencies also had to explain their process, and thus couldnt do as much. Now we only think of the political nature of agencies (not their expertise). Can we figure out ways of making expertise more important in the administrative process? Agencies are now made more of career civil servants than technical experts. This does not fit with the progressives notion of the expertise of agencies B. Structure of Administrative Law Adjudication vs rule-making

21

If an agency is affecting a small group, they are adjudicating. If an agency is affecting a large group, they are rule-making. (Bipolar v. Polycentric) You may think this distinction came under pressure because modern courts deal with polycentic disputes, such as class actions. However, it didnt come under pressure. If agencies are involved in adjudication, they must go through procedural hoops, such as cross examinations and formal rules of evidence. This is expensive. Thus, agencies do not want to classify their actions as adjudication if they dont have to. Agencies have discretion about whether to proceed by adjudication or law making. (Qualification: some statutes force agencies to proceed in certain ways, but this is rare). They must decide whether they want a case-by-case response. Sometimes they dont want a rule to apply too broadly, and thus they adjudicate. Agencies can engage in two types of rule-making: formal rule making & notice and comment rule making Formal rule making: Stringent procedure requirements are necessary, such as oral testimony and cross examinations. In addition, they must give notice to everyone affected. Formal rule making is extremely burdensome, and is only used when Congress mandates it (rarely). Notice & Comment rule making: Procedure described in Section 553, judicial review described in Section 706 of APA C. Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Natural Resources Defense Council (Rehnquist, p 427)- Judicial Review of Agency Rule-Making Vermont Yankee seeks a permit to build a nuclear power plant In the licensing proceeding, the issue of disposing spent fuel is not brought up. NRDC objects to this The atomic energy commission (AEC) will come up with a rule to tell licensing body how to address the spent fuel issue Notice- they make this a rule-making proceeding, and not adjudication Steps in rule-making proceeding (notice and comment): 1) Notice must contain the terms of the proposed rule and a description of the issue involved. In addition, it must include a statement of the time and place of proceedings, and their legal authority to make the rule. (see page 426) In this case, the notice gives 2 proposed rules: 1) Licensing proceedings will not need to take disposal into account since risk is slight 2) Numerical value for the impact of fuel disposal must be fitted into cost/benefit analysis during licensing proceedings The AEC chooses rule 2

22

NRCD opposes rule making proceedings: there were no cross examinations, and the origins of the environmental survey numbers were unclear. In addition, the decision was arbitrary and capricious. After notice, agencies must give parties the opportunity to participate in rule making. NRDCthis means meaningful opportunities to participate. In order to do this, you must cross examine people who created the environmental survey. **Supreme Court: Actually, an agency is not required to do this. The agency gets to decide whether to use procedures above the floor. There are other ways to participate. The court should not be involved in forcing above the floor proceedings. The agency can create their own procedures. Holding: the AEC rule should stand. General comments: Who should make the procedural rules for rule making? Agencies: experts who are indirectly politically accountable They know what information they need, and can therefore make appropriate procedures. However, there is process bias: agency experts may overestimate their ability to know what information they need Courts: Not politically accountable, so maybe they shouldnt be making procedures. However, they are experts in procedure, so maybe they should. Congress: Generalists- they have no expertise in designing procedure. However, they are very politically accountable, and thus if the public wants lots of nuclear power, they can make procedural requirements minimal. So what makes the most sense? Unclear, but now the legislature makes basic/minimum requirements, and agencies can extend it. D. Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Association v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. (White, p 438)- Judicial Review of Agency Rule-Making Congress tells the Secretary of Transportation to develop rules that promote car safety. The agency first says that all cars must have seatbelts. It then says that cars must have automatic seatbelts, airbags, or seatbelts that must be fastened to start car. Later, it gets rid of the enhanced requirements, and says that cars only need to have manual seatbelts. Is this arbitrary and capricious? The arbitrary and capricious standard: A rule is ok if it is rational, considered the relevant factors, and within their authority (p 442) Court holding: This decision was arbitrary and capricious The agency did not consider requiring the installation of airbags specifically In addition, it is arbitrary to say that automatic seatbelts could not be efficient, even with technological advances

23

Hard Look Rule: You must give agency rational a hard look. An agency must give a reason for changing a prior decision. The court must look at technical material seriously, and make sure the rule is justified with respect to the material The Court (White) says that the Vermont Yankee rational should not apply here. Vermont Yankee dealt with actual procedures. Additional procedures add additional costs on agencies, and courts should not do this. However, the Hard Look Doctrine also leads to more costs (the agencies will need to create more intensive factual records, etc) Thus, White doesnt describe why the Yankee principle does not apply here. The Hard Look Doctrine is pro status quoIt might prevent sharp swings in rules when administrations change. However, it might be an obstruction and lead to agency ossification. **Overview: Chevron gives deference to agency statutory interpretation (usually). Vermont Yankee gives deference to agency rule make procedures. This encourages the President/policy makers to make changes without interference of the court. However, State Farm allows broad judicial review of rule making rationales. This (along with the Iron Triangle, or the relationship between agencies, legislature, and interest groups that makes it hard to make effective rules) leads to ossification. *** Thus, you defer to agencies on statutory interpretation, but compensate by taking a tough look at the rules you make based on the interpretation. E. Making Agencies Politically Accountable- Non Delegation Doctrine Non-delegation Doctrine: the legislature cannot transfer full legislative authority to agencies. The legislature must provide guidance. It is supposed to ensure that main policies are made by congress, and agencies only fill in details (since the legislature is more politically accountable). Problem with strict non-delegation doctrine: Legislation must include details which tell agencies what to do. Since Congress is not specialist, this leads to a reduction in the quality of legislation. The non-delegation doctrine is not strictly imposed. However, Congress is always allowed to insert a lot of detail about what they want agencies to do. The legislature must provide agencies with an intelligible principle regarding what they should do. F. Whitman v. American Trucking Associations (Scalia, 674)- Application of Non Delegation Doctrine The Clean Air Act requires standards for pollutants to protect public health with an adequate margin of safety, but does not specify what the standard should be. It does not specify where you should draw the line. Ozone is not a threshold pollutionit causes harm at every level above 0

24

The best analysis EPA can adopt is cost-benefit analysis. However, the statute does not consider costs, so the EPA cannot use this standard. Question: Is the statute specific enough to comply with the non-delegation doctrine? Court holding: The directive supplied by the legislature is good enough. We have approved much less specific directives than this. However, where is the intelligible standard? The non-delegation doctrine is not serious anymore. This holding (a very loose non-delegation doctrine) creates low political accountability. Thus, there must be other techniques to achieve political accountability. Why did the non-delegation doctrine die? Congress made a lot of agencies to deal with fast paced change of society and complicated technologies. Given these circumstances, it is unusual for congress to give specific standards. There is simply not enough time. Thus, Congress started giving very general instructions to agencies. If you had a serious non-delegation doctrine, you could not deal with issues in a timely manner. It would make the modern administrative state unworkable. So: Courts wont force the legislature to constrain agency action through statutory language. How can the legislature restrict agencies? How can we insure agencies are politically accountable enough? G. Making Agencies Politically Accountable by Other Means Between Congress and the Executive, to whom should administrative agencies be more accountable? Congress- more people, state-elected, shorter terms (House members) than President The Congress and Executive are accountable to people in different ways. Thus, it is debatable. INS v. Chada- when an immigrants visa expires, he goes to the INS and says that he is eligible for deportation, but he has extraordinary circumstances. The INS accepts this, and decides not to deport him. However, the Congress vetoes the INS decision (though it is not Congress as a whole that makes this decision, just a committee head). *The Court rejects the legislative veto, because it is really just adjudication in a procedurally unfair way. If a decision made by Congress has the effect of changing the rights of people, it must pass through both houses. This limits the accountability of agencies through the legislature. VII. Problems with Regulation A. Problems with Simplest Type of Regulation: Information Provisions

25

Disclosure Requirement: Proposition 65 (discussed on p. 567)- Requires grocery store managers, restaurant owners, etc. to put out warnings about agents that could cause cancer or birth defects. Problem with this regulation: 1) Warnings are so pervasive that they become meaningless; 2) Warnings are attached to things unnecessarily so that managers can avoid liability Warning signs should lead to lower prices. This doesnt work, however. Warnings are pervasive and undifferentiated, so warnings do not have the appropriate effect. Viscusi: maybe there should be different levels of warnings Problem with this: 1) inaccurate categorization; 2) costly; 3) politics may be involved in changing labels Sunstein: Designing successful disclosure laws is very difficult Problems with Disclosure: 1) Overload problem 2) If you force companies to disclose risks in order to make positive claims, you might stop companies from making true claims. This could lead to less consumer information. Hanson: Even if we have accurate disclosures, people cannot interpret them well due to cognitive biases. Thus, disclosures may make people less informed (Sunstein says this too) In general with information provisions, there is a trade off between understandability and providing useful information. Information provisions are the simplest form of regulation, but there are still problems. Four solutions: 1) Even though informational provisions are theoretically defensible, they practically dont work. Thus, we shouldnt even use this type of regulation. We should let competitors provide information about each other. 2) Design information provisions better (Viscosi) 3) We should just prohibit products if information provisions dont work well. 4) Make dangerous products cost more. B) Regulatory Paradoxes (Cass Sunstein, p 470) Paradox 1: Stringent regulation of new risks can increase aggregate risk levels. A focus on new risk perpetuates old technology, even though new options are better than old options. This incentivizes companies/consumers to keep unregulated old technology instead of improving technology For instance, new cars cant pollute as much as old cars, so they are more expensive. Thus, consumers keep old cars longer (leading to more pollution).

26

How to solve this: calculate the expected lifetime of a product. After that lifetime, you must meet the standard for new products. This is difficult, however, due to enforcement problems. We know about the old risk/new risk paradox and ways of responding. However, we continue to regulate new technologies but not old technologies. Why? 1) Political pressure from companies; 2) overvaluation of the status quo compared to new alternatives; 3) dont want to punish people for old decisions Paradox 2: Overregulation produces Under-regulation Example: For political reasons, an agency adopts a regulation which requires reduction of a certain chemical agent to a very low level. Due to this, the regulated party will fiercely challenge the regulation Given the complexity of environmental statutes, this challenge will be hard to fight, and the agency will need to spend a lot of money and time to defend the statute. In addition, the agency may lose. Money spent on defending that regulation reduces the money that can be spent on other regulations. Solution (Mendeloff): Regulate less intensively, but more extensively Reasons this solution might not be good: 1) aggregate resistance might still be just as expensive; 2) we may not want to distribute regulation this way; 3) there are political reasons for intensive regulation: if a chemical is dangerous, it looks bad to restrict it to an intermediate level Overall, there are ways to avoid regulatory paradoxes, but there are political reasons that paradoxes are not avoided. C. Regulations Make Us Poorer, and Thus Less Safe (Aaron Wildavsky, 479) If you impose regulations, you can only achieve your goal at a cost. If companies and individuals comply with regulations, you have less money to spend on other things. Society becomes less rich. When society becomes less rich, it becomes less safe. This is because rich people value safety more than poor people, and thus demand it in the market place. Poorer people do not shop as much for safer products. Thus, paying for safety improvements leads to reduction in safety. *Maybe this is a distribution problem- we should let the market distribute safety money instead of regulators. Consumers know what safety they want better than regulators. Problem: role of expertise v. consumer choice- consumers might not know how to keep themselves safe VIII. Cost/Benefit Analysis There are problems with using cost/benefit analysis in order to create regulations:

27

1) Some people object to c/b analysis in principle. There is something creepy about putting a value on a human life 2) Others object to the implementation of c/b analysis: Even if you assume you can put a value on a statistical life, regulation does not only save lives. It prevents diseases, pain, etc. If you do not factor this in, you will underestimate the benefits. However, it is hard to calculate these benefits. (Agencies have both expertise and some political dimensions. The political demension leads them to factor soft benefits) It is difficult to obtain cost estimates. Only the regulated industry has accurate information regarding costs, and they are biased. It is also difficult to obtain benefit estimates. A life saved is worth about 6 to 9 million dollars. However, should children be valued more than adults? Should rich people be valued more than poor people? It is difficult to know whether to discount, since the benefits (saving a life) are non-financial. Cost Effectiveness Analysis: Pre-set budget or goal. We will spend $100B on complying with regulations. Given that budget, what set of regulations gives us the largest safety gains? OR Our goal is to save 500 lives. What is the cheapest way to do it? C/B analysis does not begin with a budget or goal. Problem with Cost Effectiveness Analysis: It does not fit with reality. Agencies do not have fixed budgets or goals. Budgets and goals are derived from politics. You do not want to slip from c/b analysis into cost effectiveness analysis. John Morrall (p 511): Regulations with high cost per life saved tend not to be enacted, while regulations with low cost per life saved tend to be enacted. C/B analysis is used. Frank Ackerman & Lisa Heinzerling (p 518): Challenge to cost benefit analysis: Experts through out numbers, but you have no idea where the numbers came from. Alternatives to c/b analysis: cap and trade, information provisions However, these are just different forms of regulations, and they still have costs and benefits On the other hand, cap and trade relocates much of the cost-benefit analysis to the regulated companies. Still, you must use cost-benefit analysis to create the cap. Ackerman and Heinzerling do not object to a checklist, pro/con approach (Ben Franklin approach). In cost benefit analysis, after you make a list of pros and cons, you must add up the value of both columns. However, in Franklin approach, you just look at the list, and figure out what seems right. New York Times Article British Health Care System- they do not pay for treatments when the costs outweigh the benefits

28

This is a transparent use of c/b analysis with respect to human life. Memo from John D. Graham to Agency Heads (2001) Describing OIRA review Executive Order 12866: agencies must use cost-benefit analysis for significant regulatory proposals. Each year, agencies must send their proposed agendas to OIRA. OIRA asks questions about why they are planning on doing certain things. Proposed rules are also sent to OIRA, along with cost-benefit analysis. OIRA will assess whether the cost/benefit analysis was good. If the agency departed from cost/benefit analysis, OIRA will judge the explanation for not using it. If the agency does not meet OIRAs standards, the regulation is sent back to the agency for change. Public policy behind OIRA oversight: 1) Prevent agency capture by the regulated industry 2) OIRA is a generalist, and agencies are specialists (different perspectives) 3) More accountability/transparency 4) OIRA is synaptic: it can observe all agencies, and thus know how agencies generally work 5) There is process bias at the agency level (experts may be biased due to their expertise, and think about benefits more than costs) OIRA is under White House control instead of Congress control. The oversight committee in Congress is relatively specialized. Congress might not function well as a generalist oversight body, since the duties will be given to special committees. Criticism of OIRA: It can be captured as well, and thus can lead to more access for industries. In addition, it is a second level that slows down the adoption of regulation. IX. How Politics Effects Regulation There are two types of regulation: Special Interest Regulation: regulation of specific industry, concentrated benefits Ex. Regulate a chemical used in steel making. Benefits: unionized steel makers; costs: steel consumers (if the steel makers pass on the costs) There is a large benefit to a small group (steel workers) and a small cost to a large group (consumers) Consumers wont be lobbying, but steel unions will be. Thus, the bill can be enacted even if costs exceed benefits. There are policy entrepreneurs who advocate on behalf of diffuse interests. However, they are under-funded and cannot compete. Public Interest Regulation: Diffuse benefits, either diffuse or concentrated costs Ex. A statute which prohibits lead in toys; an agency regulates pollution *How are these passed if there are diffuse benefits? David Mayhew (700): 1) Legislatures are motivated by concern for election/re-election

29

2) They are also motivated by the desire to make good policy, as long as they can still get elected (this is especially important in their last term) Politicians vote for regulations in order to advertise, take positions, and claim credit Credit Claiming: Politicians want to take credit for passing some regulations. Thus, they get on committees or become one of the first 5 sponsors of bills. Position Taking: Politicians what to state what their positions are with out policy consequences. They get political credit for just taking a position. Thus, they often show that they care by passing regulation responsibility to agencies. At the agency level, when there are diffuse benefits but concentrated costs, the regulated companies may prevail or shape regulation. However, members of congress wont have to take responsibility for caving into coal producer. Thus, there may be public pressure to do something, but nothing happens (other than the creation of an agency). X. Comparing US Regulation to Other Countries A. Great Britain (David Vogel, 743) In the British system: Stakeholders meet and generate a rule. They then bring the rule to an agency for rubber stamping. This is the corporatist mode. Overall, there is no significant difference in the effectiveness of US and British regulation. The British tend to use general principles and standards in order to regulate. The USA tends to use specific rules. In order for the British system to work, the population must trust that the stakeholders will produce something in the public interest. We have less trust in the US. Benefit of British system: Everyone is talking in a transparent way. This is different from the czar method in the US. We dont know who is influencing the czars. Enforcement: In England, the enforcement is very flexible, nuanced, and plant-specific. It is more cooperative. The regulators send someone to the plant to discuss fixing the problem. The regulators trust the companies. In the US, we fine companies for non-compliance. In England, the firm inspects itself (there are internal safety teams). In the US, there are external inspections and reporting requirements. These reports are sent to the agency to make enforcement decisions OR released locally so the local population demands change. B. Japan In Japan, there is lots of violence/disorder in response to risk-creation (such as pollution). This is partially because you cant easily get redress from the legal system (Sanders) In Japan, apologies are important. Aggrieved people want an apology as much as monetary compensation.

30