Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

A Study of The Potential Economic Impacts of Commercializing A General Aviation Airport

Hochgeladen von

Jeremy Paul StephensOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A Study of The Potential Economic Impacts of Commercializing A General Aviation Airport

Hochgeladen von

Jeremy Paul StephensCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A Study of the Potential Economic Impacts of Commercializing a General Aviation Airport

by

Jeremy Paul Stephens

A Graduate Capstone Project Submitted to ERAU Worldwide in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Management

Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide Atlanta Campus March 2012

A Study of the Potential Economic Impacts of Commercializing a General Aviation Airport

by

Jeremy Paul Stephens

This Graduate Capstone Project was prepared under the direction of the candidates Project Review Committee Member, Dr. Merrill E. Douglass, Associate Professor, ERAU Worldwide, and the candidates Capstone Review Committee Chair, Dr. Debra Bourdeau, Director of Academics, Atlanta Campus, ERAU Worldwide, and has been approved by the Capstone Review Committee. It was submitted to ERAU Worldwide in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Management

Project Review Committee:

//SIGNED// ___________________________ Merrill E. Douglass, D.B.A. Committee Member

//SIGNED// ___________________________ Debra Bourdeau, Ph.D. Committee Chair

ii

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to thank those who made this project possible. I would like to thank Drs. Debra Bourdeau, Merrill Douglass, and Charlie Allen, for their guidance throughout. I am also grateful to the following people for taking their time to discuss my project and providing access to vital research data: Brett Smith, Propeller Investments; Amanda Hill, Georgia Department of Transportation, Aviation Programs; and Trisha Lambert, New Hampshire Department of Transportation, Bureau of Aeronautics. I owe my deepest gratitude to my wife, Kara, and my entire family, whose support and encouragement made this all possible.

iii

Abstract Researcher: Title: Jeremy Paul Stephens A Study of the Potential Economic Impacts of Commercializing a General Aviation Airport Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Master of Science in Management 2011

Institution: Degree: Year:

The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential economic impacts of commercializing a general aviation airport. The study investigated the possible overall economic implications in the forms of direct, indirect, and induced monetary effects; the number of jobs commercialization could add; and the effect of a commercial airport on local property values. Utilizing quantitative methods, economic and passenger data collected from economic impact studies completed at the federal, state, and airport authority levels were used to test the scientific hypotheses. Data was obtained from a sample of general aviation and commercial airports, which are approximately the same sizes as the current operations and the proposed commercial operations for the airport at Briscoe Field, Lawrenceville, Georgia. A primary goal of this research was to determine if commercialization is an effective way of generating additional revenue and promoting economic growth in the local area.

iv

Table of Contents Page Abstract List of Tables Chapter I Introduction Background of the Problem Researchers Work Setting and Role Statement of the Problem Purpose and Importance of the Study Assumptions Limitations Delimitations List of Definitions List of Acronyms II Review of Relevant Literature and Research The Search for New Revenue Streams Privatization Gains Momentum Lessons from the United Kingdom The Aerotropolis Property Value Concerns Economic Impact Studies Summary 8 8 10 11 11 11 12 12 12 13 14 14 16 19 20 21 24 27 iv vii

Statement of the Hypotheses III Research Methodology Research Model Target Population Sources of Data Treatment of the Data Sub Problem One and Hypothesis One Sub Problem Two and Hypothesis Two Sub Problem Three and Hypothesis Three IV V VI VII Results Discussion Conclusions Recommendations

27 29 29 29 29 30 30 31 31 33 39 41 44 46

References Appendix A Table of Economic Studies

49

vi

List of Tables Table 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Decibel Level Study on Aircraft Takeoff: Select Aircraft Sample Economic Impact Summary Sample Median Property Values Near Airports Airport Enplanement and Economic Activity Airport Enplanement and Jobs Created Commercial Airport Median Property List Values General Aviation Airport Median Property List Values Page 23 25 31 32 33 35 36

vii

Chapter I Introduction Background of the Problem Since the Wright brothers introduced aviation to the world, this sector has grown from strictly the domain of militaries, governments, and the privileged few, to a means of transportation for businesses and recreational travelers of all income levels. Bill Gates stated that the Wright brothers ushered in an age of globalization, as the world's flight paths became the superhighways of an emerging international economy (Air Transportation Association of America, 2001). The positive economic impact of the aviation industry in the United States is undeniable, as civil aviation accounted for 12 million jobs and $1.3 trillion in total economic activity, equating to 5.6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), in 2007 (Federal Aviation Administration, 2009). Just from these facts alone, it is easy to see the effect aviation has on the economy at large. As the current recession continues to drag on throughout the country, it is becoming increasingly important for local governments to find methods in which to remain fiscally responsible while still providing their citizens with the necessary services to function as a safe, happy, and healthy society. Local governments are analyzing and debating options that will allow them the ability to tighten the budget, while at the same time creating new revenue streams that will keep them from cutting necessary services such as police and fire protection (Dugan, 2010). One option that is available to the government of Gwinnett County, Georgia, is the privatization and subsequent commercialization of the general aviation airport that it currently owns, Briscoe Field, in Lawrenceville, Georgia.

Privatization is the act of transferring a commodity, business, or object from public or government control, to that of a private entity or enterprise. If one considers all management activities that the operation of an airport requires, airports in the United States are actually some of the most privatized in the world. While the actual ownership of airports in the United States still lies mostly with State or Local governments, only 10% to 20% of the workers at these airports are typically government employees. Virtually all services available at an airport are owned and operated by a private entity. This arrangement of ownership contrasts deeply to the model in most of the rest of the world, where virtually every aspect of an airport is controlled by the owning government. This situation is what has lead to massive privatization of airports throughout the world. Despite the level of privatization that has been achieved, these governments still exercise some form of regulation or minority ownership in the airport due to concerns over monopoly business practices, and to protect the public interest in an enterprise such as air travel (Neufville, 1999). While the level of privatization at an airport, such as Briscoe Field, is something that will need to be addressed with the best interests of the community in mind, the reason behind pursuing privatization is one of fiscal concern. Due to the airport grant-funding guidelines from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), it is federal law that any profits from the operation of an airport must be used strictly for the airport (Poole, 2006). Because Gwinnett County has received funding from the federal government for Briscoe Field, it is precluded from using any profits derived from operations at the airport for other budgetary line items, such as education, police, fire, or infrastructure (Poole, 2006). The privatization of Briscoe Field would allow Gwinnett County to use profits from the airport to fund a myriad of other projects and line items

within its budget, thus releasing one of the constraints that it faces in the current economic climate. Based on this information it is evident that the primary concern in this matter is not the privatization of Briscoe Field, but how to increase revenue from the airport. The currently proposed method in which to increase the airports revenue and profitability is in the addition of commercial service at Briscoe Field. This would transform the airport from strictly a general aviation airport to a regional community airport which offers both general aviation and commercial passenger services. Leading the way in the case for commercialization of Briscoe Field is Propeller Investments. Propeller has stated in their proposal that they will build a passenger terminal with 10 gates that is capable of handling four commercial flights per hour, or about 2.5 million passengers per year. Propeller estimates that in approximately 10 years, when the airport should reach peak capacity, it will also account for 20,000 direct and indirect jobs (Fly Gwinnett Forward, 2011).

Researchers Work Setting and Role The researcher is a Master of Science in Management student at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Atlanta, Georgia, campus, and has a Bachelor of Science in Technical Management from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. The researcher has 12 years of practical and academic experience in the aviation industry, and has completed coursework in Airport Management, Airline Management, Macroeconomics, Microeconomics, Strategic Management, and World Economic Analysis.

10

Statement of the Problem It is already evident from the facts stated in the FAAs civil aviation study that the aviation industry has an enormous impact on the economy. What sort of impact would a commercial airport have on the economy of Gwinnett County? How much revenue could the proposed airport generate, both directly and indirectly? To what extent would the new airport affect the number of jobs in the area? Would the airport cause an increase or decrease in area property values? This study is focused on answers to these questions.

Purpose and Importance of the Study With Gwinnet County searching for ways to increase revenue to the county without raising citizens taxes or cutting necessary community services, it is vitally important that the option of privatizing and commercializing the countys general aviation airport be thoroughly studied. If commercialization is shown to be an effective way of generating revenue and boosting the local economy, the county could then use the increase in revenue to bolster its services and infrastructure.

Assumptions The first assumption is that the proposals of privatization and commercialization are independent issues and thus should be studied independently. The second assumption is that all data collected and presented by third parties is accurate and without bias. The third assumption is that the sample is sufficiently large and sufficiently representative of the target population to warrant the findings and conclusions. The fourth assumption is that 2.5 million enplanements for a commercial airport the size of Briscoe Field is realistic. If additional research indicates that the

11

target number should be higher or lower, the hypotheses to be tested will be adjusted accordingly. Refer to the Treatment of Data section in Chapter III for a discussion of the data analysis.

Limitations The limitation of this study is that the economic impact studies, from which all data were derived, were completed in different years. In an effort to properly analyze the data, the figures given will be adjusted for inflation to 2010 dollars in an effort to obtain accurate statistical analysis of the problems.

Delimitations Because the researcher was interested in using the results of this study in relation to Gwinnett County airport, the population from which the sample was drawn was limited to those airports with one million to four million enplanements. The findings and conclusions are based on an investigation of the variables identified in the problem statement and sub-problems. Unidentified confounding variables may have a negative impact on the findings and conclusions. Although the research report is free of intentional bias, the researcher recognizes the probability of bias of some type and cautions the reader to be cognizant of that possibility.

List of Definitions Enplanements - The number of passengers boarding an aircraft at an airport. Does not include arriving or through passengers.

12

Commercialization - the act of commercializing something; involving something in commerce; in aviation this typically consists adding commercial airline service to an airport. Noise Contour Band existing level of noise exposure as delineated on a map. Bands are expressed in highest decibel level of exposure within the marked area. Example: 65 dB Noise Contour Band. Privatization - act of transferring a commodity, business, or object from public or government control or ownership to that of a private entity or enterprise.

List of Acronyms BEA DOT FAA GA GAA GDOT Bureau of Economic Analysis Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration General Aviation General Aviation Airport Georgia Department of Transportation

13

Chapter II Review of Relevant Literature and Research The Search for New Revenue Streams Due to the current economic climate, cities, counties, and states are looking for ways to meet budget gaps created by lower tax revenues and unfunded pensions. According to Dugan, these municipalities are searching for assets to sell or lease to private entities and using the funds generated to plug holes in their budgets. Local and state governments are selling or leasing everything from airports to zoos, including buildings, parking and toll services. Dugan also says that municipalities traditionally do a poor job of running these types of services and infrastructure is deteriorating because of the shrinking revenues. Many of these deals are being cited as a one-time budget maneuver, used to plug a hole in the budget with little regard as to the long-term fiscal effects of such endeavors. The key to brokering deals regarding public assets is to ensure that there is a viable model that will increase long-term revenue for the government. This will enable them to build more long-term assets, boost efficiency, and avoid raising taxes. Governments must also be sure that the private investor takes on the operating risk, and that the risk to taxpayers is minimized, both in the short and long term (Dugan, 2010). Dr. Neufville (1999) argues in his paper Airport Privatization Issues for the United States, that if the entire structure of the airport business, including planning, design, finance, and management is taken into consideration, the United States airport industry is actually one of the most privatized in the world. He contrasts the global and United States industry structures in the following manner: In most other countries airports have been: The complete responsibility of the national government,

14

Financed by the national government, and Entirely controlled by political masters through a national civil service centered on the capital. In the countries with centralized national control over airports there have been correspondingly enormous opportunities for the devolution of initiative away from the political capital toward local communities, and away from governmental processes toward a competitive commercial environment. In the United States, commercial airports have traditionally been: Independent of national control, being operated locally by municipalities or regional authorities; and Decisively influenced by competitive private interests, particularly by airlines that have had the power (through their ability to veto airport projects through the majority-ininterest clauses of their leases) to shape virtually all the major aspects of airport development and management. (Neufville, 1999, pp 8-9) Dr. Neufville states that the privatization of airports can take on many forms. A government considering privatizing its airport should look at the full range of options available and take into account the degree of government participation and strategic direction necessary for the public good, in addition to the debate of the issue of actual ownership. He also makes the point that activities which involve a substantial public interest should not be relegated solely to private interests. If the activity is central to the communitys welfare, and potentially open to, monopolistic exploitation of the public, then that activity should not be completely privatized. He suggests that a shared partnership in which the government maintains strategic control to protect the public interest is the best path to privatization of airports in the United States.

15

Privatization Gains Momentum Privatization has garnered a lot of interest lately due to legislation passed in 1996 which created the Airport Privatization Pilot Program. As summarized by Robert Pool in his article, Should Milwaukees Airport be Privatized? this legislation allows up to five U.S. airports to be privatized whether that be through sale or long-term lease. The federal funding regulations that require repayment of a portion of received federal grants upon sale of the airport would be waived, as long as airports agree to abide by all standard grant agreements in the future. Under this program the restriction by grant agreements that no airport revenue may be used for any other purpose other than the funding of activities and projects at the airport, is lifted. Municipalities may use ongoing profits from operations at the airport so long as a super-majority (65%) of airlines serving the airport approve. The specifics of the program and funding requirements can be found in the Privatization Pilot Program statute 49 U.S.C. 47134. Also in his article, Poole mentions that privatization is a good move on the citys part because airport companies create additional value to the airport by reducing costs, and increasing revenues. In the case of Milwaukees airport a private company could increase the passenger facility fee by $1.50 per enplaned passenger. Based on the number of enplaned passengers per year at the airport, this could mean an additional $4.5 million each year in revenue. He also states that airport companies further commercialize airports in an effort to increase revenue from other sources, specifically in the area of concessions. His cited example, Portland, OR, generates close to $9 per passenger in retail concessions compared to Milwaukees $1.50 per passenger. By increasing revenues in other areas, private companies are able to negotiate affordable rates and charges for the airlines serving the airport. Steps such as these

16

have allowed recently privatized airports to become more commercialized, increase their revenue as well as increase their profitability and market value. (Poole, 2006) According to an article appearing in the December 2008 edition of Airline Business, The United States still lagged behind the rest of the world in the push to privatize the ownership of airports. The author, David Field, notes that at the time, only one airport in the U.S. had been privatized: New York States Stewart Airport. This airport has since been sold to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey because the initial investors decided to leave the airport business to concentrate on other facets of transportation. Field also notes that other forms of privatization have begun to increase in popularity. Indianapolis was privately operated for ten years between 1995 and 2005. It was the first large airport to be privately operated in the U.S. During the course of private operation, the airports net profit increased from $17 million to $28 million. At the time of the article, Midway (Chicago) was undergoing the final negotiations to become the first airport to take advantage of the Airport Privatization Pilot Program. It was also the programs only large hub-style airport allowed to participate. The agreement took several years to negotiate to ensure that all parties would be treated equitably, including airlines, customers, union workers, and the new owners. The agreement went as far as to ensure airlines would only see limited fare increases by freezing them for six years and then linking them to inflation rates for the entire lease. All that remained of the privatization was FAA approval. The author also emphasizes that in the arena of privatization, it is imperative that guidance and oversight is still required from the government. His point is illustrated by the following quote from International Air Transport Association (IATA) director Giovanni Bisignani: I don't care who owns the airport. An airport is important for what it delivers not who owns it. Providing the right incentives is the most critical part of the privatization

17

process. We have seen too many privatizations fail because governments sold the crown jewels without appropriate guidance to the new owners. Look at London Heathrow. Failed regulation allowed for a 42% profit margin. The new Spanish owner is happy but Londoners suffer with terminal facilities politely described as a national embarrassment. There is no need to repeat the mistakes of others. (Field, 2008, p45) While privatization at Heathrow allowed for an outstanding profit margin, the new owners did not improve services at the airport, resulting in unhappy customers. Field insists that the types of negotiations that took place in the privatization of Midway are imperative to ensuring profitability for all parties involved in the process. (Field, 2008) Not long after the article by Field was published, the process to privatize Midway quickly fell apart. This was a direct result of the fact that the soon-to-be owners could not obtain the financing required to fulfill its $2.52 billion bid. Due to this, Chicago decided to cancel its application to privatize Midway. In an article appearing in Air and Space Lawyer in 2010, David Bennett posits that the failure of privatizing Midway is not indicative of what would happen with other airports. Two of the major hurdles in privatizing Midway were, first, that it is one of the 29 large-hub airports in the United States. Because of its size and the number of carriers that are contracted at the airport, the negotiations and contracts that needed to be navigated were unique to the situation. Second, there was no growth potential at Midway. Due to its size and a state law that prohibited boundary expansion, the options to increase revenue and realize a sizable return on the investment from a purchase were few. Bennett states that this is in contrast to airports cited by the FAA in its 2004 report to Congress concerning airports that were in the process of applying for participation in the same program. All of the mentioned airports were underdeveloped in some fashion, and there was a large potential for future development and

18

growth of revenue. Bennett further points out that there are still other forms of privatization available to airport owners, such as lease-management agreements, that do not fall under the privatization pilot program. He states that airport owners who are specifically searching for a way to remove restrictions placed on revenue usage from the airport are best served by this program (Bennett, 2010).

Lessons from the United Kingdom In their paper on airport privatization, commercialization, and regulation in the United Kingdom, authors Humphreys, Francis, and Fry (2001) state that the pressures of funding future development and growth of the airport business have led governments all over the world to consider the options of privatization and commercialization. In the early 1980s, the U.K. realized that it could not possibly continue to fund the growth necessary for this vital economic link. The authors show that the governments deficit disappeared due to privatization of 50% of the public sector between 1979 and 1991. A large part of the massive privatization occurred with the 1986 Airports Act. The purpose was to provide for the introduction of private capital to encourage enterprise and efficiency at the major airports. The authors found through this study that there was, a general trend of traffic growth, financial self sufficiency, increased emphasis on commercial revenue, and increased marketing activity in all of the privatized and commercialized airports (Humphreys, et al., 2001, p 16). Eighty-seven percent of airports experienced a growth of 15% of commercial income. All airports included in the study saw an increase in profitability; however, a few of the airports had reinvested profits into expansion projects which affected the overall amount of increase. The authors conclude that this level of growth is directly attributed to the removal of the financial burden of airport operation from the

19

government. Through varying degrees of commercialization and privatization, airports can realize a growth in profit. They also further conclude that with the, removal of such a financial burden from the state, potential increase of the tax base, and improved commercial performance could be achieved with protection against loss of control, monopoly abuse, and diversion of funds (Humphreys, et al., 2001, p 16).

The Aerotropolis According to John D. Kasarda, airport owners looking to maximize the economic footprint of their airport are expanding their horizons beyond just that of commercial air service. He states that through various commercial endeavors, airports and their immediate surroundings are becoming commercial anchors in their area. Passenger terminals no longer house rows of seats for passengers to wait in; they are now becoming shopping malls, art galleries, and recreational venues. Some airports have even gone further by adding gourmet and culinary clusters, meeting venues, high-end designer clothing stores, cinemas, saunas, and even a tropical butterfly forest. This extra commercialization in airports leads to increased revenue and profits for the airport. The long shopping corridor alone in Dubai Internationals terminal pulled in $1.1 billion in sales in 2008 (Kasarda, 2009). Mr. Kasarda states that airports are quickly becoming economic powerhouses, and that the economic influence is extended beyond simply transit-oriented development. There are even airports that alone employ over 50,000 workers, which by definition of the U.S. Census Bureau, qualify the airports as cities. Airport retail space actually pulls in more revenue than the average shopping mall. These stores generated between $600 per square foot and $2,500 per square foot in sales in 2007, depending on location. The average non-anchor tenant in a shopping mall only

20

generates $450 per square foot says the International Council of Shopping centers. Retail sales at some airports in the world are growing at a 20% rate (Kasarda, 2009). As more developers recognize the economic potential of an airport, they are slowly creating what the author dubs as an airport city. Developers are adding hospitality, entertainment, and recreation clusters, office and retail complexes, conference and exhibition centers, and more. The Sofitel Lux Le Grand hotel at London Heathrow is the nations thirdlargest conference venue. As more and more developers see the economic benefits of airports, these airport cities are morphing into new anchors of development. As the business and commercial clusters expand in the area of airports, these airport cities are giving rise to the aerotropolis. These aerotropolises are the reflection of the economys need for connectivity, speed, and agility (Kasarda, 2009). Airport areas are also attractive to business sector services and are increasingly drawing corporate regional headquarters and various other sectors which require executives and staff to frequently engage in long-distance travel. These types of airport cities are also attractive to the technology sector as high-tech professionals tend to travel more frequently than most other workers. The author states that this trend of aerotropolis development will continue as commercial aviation continues to drive economic development. He also states that urban regions would be wise to position their airports as a critical infrastructure asset for the region that must compete and attract investment and development (Kasarda, 2009).

Property Value Concerns While there are numerous potential benefits that may be realized from a commercial airport in an area, the impact that airports have on area property values is a major concern.

21

Citizens for a Better Gwinnett Inc. is a Georgia 501(c)(3) non-profit corporation organized for the purpose of promoting civic betterment and improving the quality of life for the residents of Gwinnett County, Georgia (Citizens for a Better Gwinnett, 2012). This group is a vocal opponent to any type of commercial service at Briscoe Field, and its primary complaint with commercialization is that it will decrease area property values due to noise, traffic, and pollution (MyFoxAtlanta, 2010). In his 1997 study of property values in the vicinity of the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), Randall Bell showed that a propertys proximity to an airport has a continued negative impact on its value, and that single-family residences near airports are worth considerably less than comparable properties that are located elsewhere. Mr. Bell states that diminution in value ranges from -15.1% to -42.6% and averages -27.4%. He also states that although there are over 200 factors that affect real estate values, an airport is classified as a Class V Detrimental Condition, meaning that it is an imposed condition. He defines this imposed condition as, an act or forced event that affects value, usually long-term or permanent (Bell, 1997). Bells study also included data for commercial properties as well. His study found that despite having readily available and convenient transportation access, commercial properties in the vicinity of LAX had rental rates that were 19.1% to 43.3% lower than any other office market in the surrounding area. He also notes that the vacancy rate of 38.1% was the highest in the area as well (Bell, 1997). In a study published in 2004, Daniel McMillen noted that the majority of studies concerning airport noise and property values are in agreement that airports reduce local property values. His study found that home values were about 9.2% lower in the area within the 65 dB noise contour band. Although this is on the high side of empirical studies stated by McMillen,

22

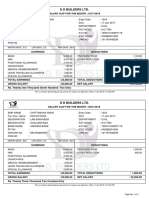

he notes that this may be due to the excessive amount of aircraft traffic at Chicago OHare as well as the denseness of the population in the surrounding area. He also mentioned that recent studies were conducted on airports smaller than that of Chicago OHare. McMillen also found that due to the quieter engines that are now being used by modern aircraft, the 65dB noise contour band had contracted by a third, and that property values in the now quieter area had actually increased. His study also showed that because of the proposed expansion, which would reroute a portion of air traffic, and quieter aircraft engines, that the property value in the area of the airport would actually increase by a total market value of $284.6 million (McMillen, 2004). The findings of McMillen are echoed in the information published by Propeller Investments. If Briscoe Field is developed as they propose, the aircraft that will be able to make use of the airport are actually quieter than the aircraft that currently make use of the airfield (Fly Gwinnett Forward, 2011). This information is reported in Table 1.

Table 1 Decibel Level Study on Aircraft Takeoff: Select Aircraft Current Aircraft Gulfstream II Learjet 24D Global Express Cessna 206 dBA 84.2 80.6 74.6 70.2 Proposed Aircraft MD90 Boeing 737-700 Airbus A-319 Boeing 717 dBA 73 65.8 65.7 64.7

23

Economic Impact Studies The economic impact that Mr. Kasardas aerotropolis provide to the country are best presented by economic impact studies. The most recent federal economic impact study was completed by the FAA in 2009, and utilizes data from 2007. This impact study shows that the aviation industry generated 12 million jobs and $1.3 trillion in total economic activity for the United States in 2007. The total economic activity of $1.3 trillion is equal to 5.6 percent of the GDP. Many states in the U.S. also release economic impact studies on the aviation industry in their region. These studies are broken down by airport and compiled for state-wide information. Due to the far-reaching economic impacts of any industry, some of the impacts cannot be directly measured quantitatively. Economists and planners use software that estimates the figures that cannot be directly quantified, such as an industrys secondary or multiplier impacts. The aviation industry uses either the Bureau of Economic Analysis Regional Input-Output Modeling System (RIMS-II) or the IMPLAN software to produce a measure of the industrys total economic impact. The FAA study utilized the RIMS-II software to estimate secondary impacts. In this software, primary economic impact data is collected from direct and indirect sources, and entered into the system. The software then uses a series of multipliers based on known data from 500 different industries, including spending, income, worker and proprietor wages, and industry structure and trading patterns to estimate secondary impacts. This data can be scaled down to a regional or local level for a more accurate estimate of the associated impacts (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 1997; FAA, 2009).

24

Primary impacts are defined as the summation of direct and indirect economic impacts, which include: air transportation and supporting services; aircraft, engines, and parts manufacturing; travel and other trip-related expenses by travelers. The direct impacts are a result of manufacturing and transportation as measured by employment, payroll, and sales generated by the following: scheduled and non-scheduled airlines and air couriers, airport and aircraft service providers, air cargo, general aviation (GA) operators including flight schools, and manufacturing. The indirect impacts are derived from the expenditures of air passengers other than airfares and other fees paid directly to airlines. These visitor expenditures create sales, payroll, and employment for the following industries: accommodations; restaurants, bars, fastfood outlets and stores; arts, entertainment, and recreations; travel services such as sightseeing and other tourist services; ground transportation; other on and off airport purchases of goods and services. The main identifying factor of primary impacts is that these impacts are all directly quantifiable (FAA, 2009). Secondary impacts, also known as induced or multiplier impacts, are estimated by the software based on the data input from the primary impacts and the set of multipliers related to the given industry. These secondary impacts are a result of the expenditures made by industries included in the primary impacts to supporting businesses, as well as the spending of direct and indirect employees. These induced or multiplier impacts account for the secondary impacts to the economy such as direct and indirect sales, and payroll impacts that are disseminated throughout supporting industries in a series of multiplier effects. For example, employees at the airport spend their salary for housing, food, and recreation. These expenditures create more jobs, payroll, and further increased spending throughout the region. The RIMS-II software uses all of the information to calculate the induced economic impact through expenditures, earnings, and

25

jobs creation. Economic impact studies that use this software can reliably report information as summarized in Table 1 (FAA, 2009).

Table 2 Sample Economic Impact Summary Primary Impacts Output Industry 1 Industry 2 Totals $$$ $$$ $$$ Jobs ### ### ### Multiplier Impacts Output $$$ $$$ $$$ Jobs ### ### ### Total Impacts Output $$$ $$$ $$$ Jobs ### ### ###

The IMPLAN software is an economic impact modeling software that is similar to the RIMS-II software. The major difference is that the IMPLAN software uses what is referred to as Social Accounting Matrices (SAM) to calculate the multiplier effects in a given economy. These matrices are developed by capturing the actual dollar amounts of all business transactions taking place in a regional economy as reported each year by businesses and governmental agencies (Alward, 2009), as well as non-market transactions such as taxes. The information used to build each SAM is derived from unique local and census information, and is not estimated from national averages. The multiplier models are built directly from the SAM for a given region which reflects its unique structure and trade situation. Because of these factors in its

26

design, the IMPLAN model is more accurate in estimating induced economic impacts than other modeling software (Alward, 2009).

Summary While privatizing airports in the United States is proving to be a slow process, there are many things that can be learned for ongoing privatization in other areas of the world. Studies show that privatization can increase profits at an airport; however, due to the public interest in such a vital infrastructure, government guidance or oversight is necessary. These reports also show that the level of privatization is not necessarily the largest factor in airport profitability. The other major factor is the level of commercialization that is developed at or around the airport, whether that be the addition or expansion of commercial flights, shopping and dining choices for travelers, or the development of the surrounding areas for industries that rely on airports for their livelihood. Conflicting studies show that airports can decrease or increase the value of property in the vicinity. The effects can be positive or negative based on the orientation of the runways, and the types of aircraft and engines used. Finally, the impact study performed by the FAA proves the enormous impact that aviation has on the economy. If airport owners and developers take all of this information into consideration and act appropriately, their airports can become the hub of an economic powerhouse for their areas.

Statement of the Hypotheses Based on the review of literature and personal experience, the following three hypotheses are posited for this study.

27

Hypothesis One: Commercialization of Briscoe Field would result in at least $1.5 billion per year in economic activity for the area. Hypothesis Two: Commercialization of Briscoe Field would account for at least 20,000 jobs, once the airports full operating capacity has been reached. Hypothesis Three: Commercialization of Briscoe Field would, in general, decrease the median property value within the area of the three closest zip codes.

28

Chapter III Research Methodology Research Model This research project will be based on the quantitative method using economic and passenger data collected from various federal, state, and airport authority conducted economic impact studies to test the scientific hypotheses. The overall strategy for the research is to estimate the impact of selected variables if the airport at Briscoe Field should be converted from a general aviation airport to one that offers commercial flights. Data will be obtained for a sample of airports, general aviation and commercial, which are approximately the same sizes as Briscoe Fields current operations and the proposed commercial operations.

Target Population The target population for this study will consist of commercial airports in the United States that are about the same size as the proposed commercial operations at Briscoe Field. The proposed passenger terminal for Briscoe Field can process 2.5 million enplanements per year. Airports used for this study had more than 1 million enplanements, and less than 4 million enplanements per year. Findings and conclusions may be applied to any airport considering expansion from general aviation to commercial service that falls within the above parameters for number of enplanements per year.

Sources of Data The sample will include economic and property value data from 10 commercial airports in the United States. Since the target population for the findings and conclusions of this study

29

consists of airports about the size of Briscoe Field, the sample was restricted to commercial airports of similar size. Consequently, the sample was drawn from airports having enplanements between 1 million and 4 million per year. The economic data will be collected from state, local, or airport authority economic impact studies. These studies were completed in conjunction with or under the authority of the airports home states Department of Transportation. The specific data collected will include the following: total number of passenger enplanements, total economic impact in dollars, total primary (direct) impact in dollars, total secondary (indirect) impact in dollars, total multiplier (induced) impact in dollars, total number of jobs. The property value data will be collected from the real estate website Trulia.com. The median sales price for homes in the zip codes closest to the airport will be used.

Treatment of the Data Sub Problem One and Hypothesis One How much revenue could the proposed airport generate, both directly and indirectly? Hypothesis one is that commercialization of Briscoe Field would generate at least $1.5 billion in total economic activity for the area. For each airport in the sample, the direct, indirect and total economic output will be adjusted for inflation to current dollars. The same categories will then be divided by the number of passenger enplanements per year to estimate the amount of economic activity generated per passenger per year. Assuming that the mean number of enplanements per year is 2.5 million, the revenue per enplanement would be $1.5B/2.5M or about $600 per enplanement. The sample mean and sample standard deviation will be calculated. A 95% confidence interval will be used as the population estimate. If the entire

30

confidence interval is greater than $600 per enplanement, the research hypothesis will be supported.

Sub Problem Two and Hypothesis Two To what extent would the new airport affect the number of jobs in the area? The second hypothesis is that commercialization of Briscoe Field would account for at least 20,000 jobs. Assuming the commercialized airport would result in 2.5 million enplanements per year, the number of jobs per enplanement would be 20k/2.5m or about 0.008. For each airport in the sample, the number of jobs produced will be divided by the number of passenger enplanements per year to estimate the number of jobs generated per passenger per year. The sample mean and sample standard deviation will be calculated. A 95% confidence interval will be calculated. If the interval is entirely above 0.008, the research hypothesis will have been supported. In that case a test for means will be conducted. To test the null hypothesis a test for means will be conducted at the 0.05 level of significance. The null hypothesis is that the population mean is equal to 0.008. The alternate hypothesis is that the population mean is greater than 0.008.

Sub Problem Three and Hypothesis Three Would the airport cause an increase or decrease in area property values? The third hypothesis is that commercialization of Briscoe field would decrease the median property value within the area of the three closest zip codes. Five general aviation airports that are of similar size and scope to the operations at Briscoe Field will be selected from the population, and five commercial airports will be selected that are of similar size and scope to the commercial operations proposed at Briscoe Field. The median property values will be summarized in a table

31

similar to Table 2. Property values are reported as medians for a particular zip code. Averaging medians yields a nonsense number (Jones, 2004). Consequently, a test for means cannot be used to test this hypothesis. A Wilcoxon test for independent samples will be conducted at the 0.05 level of significance to test the null hypothesis that the distribution of property values for general aviation airports is equivalent to the distribution of property values for commercial airports. If the null hypothesis is rejected, the median of medians for each sub-set will be found, to determine the direction of that difference.

Table 3 Sample Median Property Values Near Airports General Aviation Commercial

$$$ $$$

$$$ $$$

32

Chapter IV Results The first sub-problem was to determine how much revenue could be generated by a commercial airport of the size proposed at Briscoe Field. Data was collected from economic impact studies completed for various airports that were close to the same scope of operations that are proposed for Briscoe Field. The proposed commercial airport will be able to handle 2.5 million passenger enplanements per year. Airports chosen for the sample reported no fewer than 1 million enplanements for the year of their study, and no more than 5 million. Table 4 summarizes the data collected for the first sub-problem.

Table 4 Airport Enplanement and Economic Activity

Airport Enplanements Total Economic Impact Impact /Passenger

Austin-Bergstrom Int. Dallas Love Field El Paso Int. Houston William P Hobby San Antonio Int. Raleigh-Durham Int. Bob Hope - Burbank Manchester-Boston Regional Fort Myers Southwest Florida Int. Jacksonville Int.

3,841,773 2,954,800 1,685,723 4,151,974 3,712,992 4,701,950 2,837,872 1,861,695 3,770,681 2,965,973

2,540,000,000.00 2,190,000,000.00 1,041,300,000.00 2,890,000,000.00 3,920,000,000.00 3,180,056,600.00 4,206,556,000.00 1,251,906,000.00 3,811,047,000.00 2,209,596,000.00

661.15 741.17 617.72 696.05 1,055.75 676.33 1,482.29 672.45 1,010.71 744.98

33

Palm Beach Int. Tucson Int. Norfolk Int. Richmond Int.

3,232,009 1,808,043 1,664,735 1,660,876

2,540,184,100.00 956,440,000.00 1,064,117,000.00 1,071,389,000.00

785.95 528.99 639.21 645.07

Note: All figures have been adjusted for inflation to 2010 dollars using the Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Inflation Calculator.

The sample mean was found to be $782.70, and the sample standard deviation was $247.45. The 95% confidence interval was found to be $639.83 < mean < $925.57. Since the entire confidence interval was found to be greater than $600 per enplanement, the hypothesis that commercialization at Briscoe Field could generate $1.5 billion in economic activity is supported. The second sub-problem was to determine to what extent the new airport would affect the number of jobs in the area. Data was collected using the same criteria set forth in sub-problem one. Table 5 contains the data collected for sub-problem two.

Table 5 Airport Enplanement and Jobs Created

Airport Austin-Bergstrom Int Dallas Love Field El Paso Int Houston William P Hobby

Enplanements 3,841,773 2,954,800 1,685,723 4,151,974

Total Jobs Created 38,920 32,745 17,613 44,839

Jobs / Passenger 0.0101 0.0111 0.0104 0.0108

34

San Antonio Int Raleigh-Durham Int Bob Hope - Burbank Manchester-Boston Regional Fort Myers Southwest Florida Int Jacksonville Int Palm Beach Int Tucson Int Norfolk Int Richmond Int

3,712,992 4,701,950 2,837,872 1,861,695 3,770,681 2,965,973 3,232,009 1,808,043 1,664,735 1,660,876

51,588 18,327 36,226 3,820 41,588 23,040 37,504 17,000 10,170 10,820

0.0139 0.0039 0.0128 0.0021 0.0110 0.0078 0.0116 0.0094 0.0061 0.0065

The sample mean was found to be 0.0091069 and the sample standard deviation was found to be 0.0034. The 95% confidence interval showed that the population mean is within the range 0.0071434 < mean < 0.0110704. Since the entire confidence interval was not above 0.008, the research hypothesis is not supported. Because the hypothesis is not supported, the test for means was not conducted. The third and final sub problem was to determine if commercialization would cause an increase or decrease in the area property value. In this sub-problem the sample consisted of

five general aviation airports of similar size and scope to the current operations at Briscoe Field, and five commercial airports of similar size and scope of the proposed operations at Briscoe Field after commercialization. For each airport in the sample, the zip codes containing the airport, as well as three of the surrounding zip codes were used for the test. The zip codes and the median property list value near commercial airports are summarized in Table 6, and median property list value near general aviation airports are summarized in Table 7. 35

Table 6 Commercial Airport Median Property List Values

Airport Dallas - Love Field

Enplanements 2,954,800

Zip 75235 75220 75209 75219

Median List Price $125,000 $265,000 $465,000 $245,000 $140,000 $190,000 $175,000 $200,000 $475,000 $280,000 $539,000 $499,000 $170,000 $178,000 $113,000 $195,000 $170,000 $190,000 $208,000 $230,000

Jacksonville International

2,965,973

32218 32011 32097 32226

Bob Hope - Burbank

2,837,872

91505 91352 91504 91506

Austin

3,841,773

78719 78742 78617 78747

Manchester Boston

1,861,695

03103 03109 03104 03053

Note: Enplanement data as reported by FAA for 2010: http://aspm.faa.gov/main/taf.asp . Median List values retrieved from http://www.Zillow.com data for Nov 2010.

36

Table 7 General Aviation Airport Median Property List Values

Airport Briscoe Field

Operations 70,807

Zip 30046 30043 30019 30045

Median List Price $110,000 $145,000 $180,000 $145,000 $120,000 $85,000 $189,000 $188,000 $199,000 $90,000 $85,000 $115,000 $130,000 $198,000 $160,000 $225,000 $130,000 $399,000 $86,000 $51,000

La Porte Municipal, TX

79,433

77571 77520 77523 77586

Aransas County, TX

79,433

78382 78377 78393 78390

Deland Municipal

77,710

32724 32174 32124 32128

Homestead, FL

72,084

33030 33031 33033 33035

Notes: Total Operations data as reported by FAA for 2010: http://aspm.faa.gov/main/taf.asp . Median List values retrieved from http://www.Zillow.com data for Nov 2010.

37

A Wilcoxon test of independent samples was conducted to determine if the median property list values were equivalent for commercial and general aviation airports. This test was conducted at the 0.05 significance level. The null hypothesis that the median property list values were equivalent was rejected because the test statistic (-6.64) based on the sample data was more extreme than the critical value (-1.96) based on probability. Since the null hypothesis was rejected, the median of the medians for property list values was determined. This test showed that the median of property list values near commercial airports ($197,500) was greater than the median of property list values near general aviation airports ($137,500).

38

Chapter V Discussion This project sought to answer questions as to the potential economic effects of commercializing a general aviation airport. The researcher asked, how much revenue could the proposed airport generate, both directly and indirectly? To what extent would the new airport affect the number of jobs in the area? And last, would the airport cause an increase or decrease in area property values? The results for sub-problem one did support the researchers hypothesis that commercializing Briscoe Field would result in at least $1.5 billion in total economic activity for the area. The 95% confidence interval was found to be $639.83 < mean < $925.57. Multiplied by the proposed number of enplanements per year of 2.5 million, the test shows that commercializing Briscoe Field would generate between $1.6 billion and $2.3 billion in economic activity. The results for sub-problem two did not support the researchers hypothesis that commercialization of Briscoe Field would account for at least 20,000 jobs. The 95% confidence interval showed that the number of jobs generated per passenger enplanement would be between 0.0071434 and 0.0110704. Using the proposed number of enplanements of 2.5 million, the researcher found that commercializing Briscoe Field would generate between 17,859 jobs and 27,676 jobs. The results for sub-problem three did not support the researchers hypothesis that commercialization of Briscoe Field would decrease the median property value within the area of the three closest zip codes. The Wilcoxon test showed that the median property list values near commercial and general aviation airports was not equal. Furthermore, finding the median of

39

medians showed that the median property value near commercial airports ($197,500) was greater than that of the median property list value near general aviation airports ($137,500). This indicates that commercialization would actually enhance property values rather than decrease them.

40

Chapter VI Conclusions As mentioned in the introduction, aviation had a national economic impact of $1.3 trillion in 2007. The review of literature showed that airports are not just an asset that merely serves as a transportation hub, but economic engines that are tied directly to the economic output of the community. This study showed the type of impact that just one small commercial airport can have on a community through its economic output, the jobs that it can create, and the effect that it has on local property values. Based on results from the economic analysis, the first hypothesis was shown to be true. A commercial airport of the proposed size of operations for Briscoe Field can statistically produce between $1.6 billion and $2.3 billion in economic activity for the area. The original problem statement of this study was to determine the possible primary, multiplier, and total economic output figures; however, due to the way different states publish their own study results, it was only possible to analyze total economic output. Data used from the various States economic impact studies can be found in Appendix A. Compared to the current economic output of Briscoe Field, which accounted for $85 million in economic activity in 2010 (Georgia Department of Transportation, 2011), commercialization would represent at least a $1.515 billion, or 1782% increase in economic output. Using the upper end of the confidence interval, the airport could be responsible for an increase of $2.215 billion or 2606% in economic output for the area. The second hypothesis proposed that commercialization of Briscoe Field would account for at least 20,000 jobs in the area. While this study failed to support this hypothesis, showing that commercialization would generate between 17,859 jobs and 27,676 jobs, the results are not insignificant. The results show that this is a significant increase over the amount of jobs that 41

Briscoe Field currently generates. According to the GDOT study (2011), Briscoe Field generates 730 jobs in the area. It should also be noted that one of the airports included in the study generated significantly fewer jobs than the other airports. Manchester-Boston Regional Airport generated 0.0021 jobs per emplaned passenger. The mean for this sample was found to be 0.0091 jobs per passenger with a standard deviation of 0.0034. This shows that the airport at Manchester-Boston is more than two standard deviations from the mean, thus including jobs data for this airport in a sample of this size may have skewed the results. The final hypothesis proposed for study was that brining commercial service to Briscoe Field would decrease property values in the area. The results of this study failed to support this hypothesis. There is a significant discrepancy in the median value between property near commercial and general aviation airports. The median value for properties near commercial airports was $60,000 higher than the median value near general aviation airports. The results of this study are opposite to the studies mentioned in the review of literature. It is the researchers opinion that the reason for this difference can be attributed to the fact that airports used for the previous studies were larger, hub-style airports. The difference in the amount of traffic at a large hub airport, and smaller airports similar to the one proposed at Briscoe Field may account for the discrepancy of this study with previous studies. It should also be noted that previous studies use an equation to determine the percentage of decrease in value in relation to the noise level and frequency near an airport. The fact that aircraft with jet engines have become quieter as technology has advanced may also account for a portion of the difference in the study results, a point which was also highlighted in McMillens (2004) study. Finally, previous studies compare property values near airports to similar properties that are not near an airport to show the approximate decrease in value that the airport causes to homes

42

in the immediate area. This study focused on comparing property values between two different types of airports, as opposed to areas with no airports. This may also account for the difference in findings of this study compared to previous studies.

43

Chapter VII Recommendations The recommendations contained in this portion of the project are strictly the opinion of the author based on the data contained throughout the first six chapters of this report. The economic studies presented, as well as the results of this project show just how beneficial a commercial airport can be to the local economy. The large increase in both the economic output and the increase in jobs would be extremely beneficial to any local government looking to boost the economy in the area. Subsequent studies in economic output and jobs areas should expand the sample to include the entire population of airports in the country that are similar to the size and scope of what is proposed for Briscoe Field. Another area that should be further examined is the performance of smaller airports that operate in close proximity to a large hub. While a few of these types of airports were included in this study (Dallas-Love Field and Bob Hope-Burbank), the researcher did not focus solely on this type of environment. A focused study on this type of commercial setup should be performed in order to gain insight as to how these types of airports are affected by their much larger competitors. As for property values, this study showed that the property values near small commercial airports are higher than those near general aviation airports. Future studies should explore possible reasons for this outcome by increasing the sample sizes in both categories for comparison. As noted in the review of literature, the residential property value is not the only concern near airports. Future studies should also take into consideration commercial and industrial property values near similar types of airports. Property value is based on an extremely large number of variables, and thus more expansive studies into this topic should be pursued.

44

Based on the literature reviewed, and the outcome of this study, it is the researchers opinion that Briscoe Field should be commercialized. The potential economic gains as a result of commercialization are too great to be ignored, and it would be a disservice to the citizens not to take advantage of the opportunity.

45

References Air Transport Association of America. (2011). Economic impact. Retrieved from: http://www.airlines.org/Economics/AviationEconomy/Pages/EconomicImpact.aspx Alward, A. (2009, June 29). What is IMPLAN? Retrieved from: http://implan.com/V4/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=282:what-isimplan&catid=152:implan-appliance-&Itemid=2 Bell, R. (1997, January 9). Airport diminution in value. Retrieved from http://www.eltoroairport.org/issues/rbell.html Bennett, D. L. (2010). Airport privatization after midway. The Air and Space Lawyer, 23(1), 11,23-27. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (1997, March). Regional multipliers. Washington, D.C.: Department of Commerce. Dugan, I. J. (2010, Aug 23). Facing budget gaps, cities sell parking, airports, zoo. Wall Street Journal, pp. A.1-A.1. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.libproxy.db.erau.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/74639 8301?accountid=27203 Federal Aviation Administration. (2009). The economic impact of civil aviation on the U.S. economy. Washington, D.C.: Department of Transportation. Field, D. (2008). Slow progress. Airline Business, 24(12), 45-45-46. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.libproxy.db.erau.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/20412 6062?accountid=27203 Fly Gwinnett Forward. (2011). Frequently asked questions. Retrieved from http://www.flygwinnettforward.com/frequently-asked-questions

46

Georgia Department of Transportation. (2011). 2011 Georgia statewide airport economic impact study. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Transportation. Humphreys, I., Francis, G., & Fry, J. (2001). Lessons from airport privatization, commercialization, and regulation in the United Kingdom. Transportation Research Record 1744, pp. 9-18. Paper No. 01-3239. Infanger, J. & McAlliser, B. (2008, August). Economically challenged. Airport Business, pp. 18-21. Jones, D. (2004). Relative earnings of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals, Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 9 (4), 459. Kasarda, J. (2009, April). Airport Cities. Urban Land. 56-60. McMillen, D. (2004). Airport expansions and property values: the case of Chicago OHare Airport. Journal of Urban Economics. 55, 627-640. MyFoxAtlanta. (2010, August, 31). Newsmaker: Briscoe field expansion. Retrieved from http://www.myfoxatlanta.com/dpp/news/newsmaker-briscoe-field-expansion-083110 Neufville, R. (1999). Airport privatization issues for the united states. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Poole, R. (2006). Should Milwaukees airport be privatized? Wisconsin Interest. Fall 2006. 1523.

47

Appendix A Table of Economic Studies

48

Appendix A Table of Economic Studies

49

Table of Economic Studies

State/Year

Airport

Enplanements

Direct Impact

Indirect Impacts

Multiplier Impacts

Total Econ Impact

Total Jobs

TX / 2004

Austin-Bergstrom International Dallas Love Field El Paso International Houston William P Hobby San Antonio International

3,841,773 $1,200,000,000 2,954,800 1,685,723 4,151,974 3,712,992 3,770,681 2,965,973 3,232,009 1,664,735 1,660,876 4,701,950 1,861,695 1,808,043 2,837,872 1,000,000,000 495,200,000 1,400,000,000 1,800,000,000 487,670,800 457,573,000 558,888,100 Not Reported Not Reported 1,103,311,100 242,400,000 Not Reported 628,100,000

Not Reported Not Reported Not Reported Not Reported Not Reported $1,589,959,400 749,736,000 1,375,642,500 Not Reported Not Reported 1,197,644,900 240,900,000 Not Reported 1,124,100,000

$1,000,000,000 900,000,000 406,900,000 1,100,000,000 1,600,000,000 1,685,301,800 974,390,000 1,560,958,000 Not Reported Not Reported 453,899,100 375,200,000 Not Reported 2,136,900,000

$2,200,000,000 1,900,000,000 902,100,000 2,500,000,000 3,400,000,000 3,762,932,000 2,181,699,000 3,495,488,600 1,064,117,000 1,071,389,000 2,754,855,100 1,236,100,000 941,000,000 3,889,100,000

38,920 32,745 17,613 44,839 51,588 41,588 23,040 37,504 10,170 10,820 18,327 3,820 17,000 36,226

FL / 2008

Southwest Florida International Jacksonville International Palm Beach International

VA / 2010

Norfolk International Richmond International

NC / 2004 NH / 2008 AZ / 2009 CA / 2006

Raleigh-Durham International Manchester-Boston Regional Tucson International Bob Hope - Burbank

Note: Dollars reported in the year the study was completed as noted in the first column. 50

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Original PDF Global Problems and The Culture of Capitalism Books A La Carte 7th EditionDokument61 SeitenOriginal PDF Global Problems and The Culture of Capitalism Books A La Carte 7th Editioncarla.campbell348100% (41)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Economics For Everyone: Problem Set 2Dokument4 SeitenEconomics For Everyone: Problem Set 2kogea2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Disrupting MobilityDokument346 SeitenDisrupting MobilityMickey100% (1)

- Nicl Exam GK Capsule: 25 March, 2015Dokument69 SeitenNicl Exam GK Capsule: 25 March, 2015Jatin YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12-11-2022 To 18-11-2022Dokument74 Seiten12-11-2022 To 18-11-2022umerNoch keine Bewertungen

- CI Principles of MacroeconomicsDokument454 SeitenCI Principles of MacroeconomicsHoury GostanianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marico's Leading Brands and Targeting StrategiesDokument11 SeitenMarico's Leading Brands and Targeting StrategiesSatyendr KulkarniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Company accounts underwriting shares debenturesDokument7 SeitenCompany accounts underwriting shares debenturesSakshi chauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- KjujDokument17 SeitenKjujMohamed KamalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thyrocare Technologies Ltd. - IPODokument4 SeitenThyrocare Technologies Ltd. - IPOKalpeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- EP-501, Evolution of Indian Economy Midterm: Submitted By: Prashun Pranav (CISLS)Dokument8 SeitenEP-501, Evolution of Indian Economy Midterm: Submitted By: Prashun Pranav (CISLS)rumiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fiscal Policy of IndiaDokument16 SeitenFiscal Policy of IndiaAbhishek Sunnak0% (1)

- Find payment channels in Aklan provinceDokument351 SeitenFind payment channels in Aklan provincejhoanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alifian Faiz NovendiDokument5 SeitenAlifian Faiz Novendialifianovendi 11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Business Model Analysis of Wal Mart and SearsDokument3 SeitenBusiness Model Analysis of Wal Mart and SearsAndres IbonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pay - Slip Oct. & Nov. 19Dokument1 SeitePay - Slip Oct. & Nov. 19Atul Kumar MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presented By:-: Sutripti DattaDokument44 SeitenPresented By:-: Sutripti DattaSutripti BardhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Bank Review Global AsiaDokument5 SeitenWorld Bank Review Global AsiaRadhakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- IAS 2 InventoriesDokument13 SeitenIAS 2 InventoriesFritz MainarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Exam - Module 2: Smooth Chin Device CompanyDokument16 SeitenFinal Exam - Module 2: Smooth Chin Device CompanyMuhinda Fredrick0% (1)

- (Sample) Circular Flow of Incom & ExpenditureDokument12 Seiten(Sample) Circular Flow of Incom & ExpenditureDiveshDuttNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On Alternative Centres of PowerDokument10 SeitenNotes On Alternative Centres of PowerMimansaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Companies List 2014 PDFDokument36 SeitenCompanies List 2014 PDFArnold JohnnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- StopfordDokument41 SeitenStopfordFarid OmariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ex 400-1 1ST BLDokument1 SeiteEx 400-1 1ST BLkeralainternationalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5d7344794eaa11567835257 1037739Dokument464 Seiten5d7344794eaa11567835257 1037739prabhakaran arumugamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Examiners' Report June 2017: GCE Economics A 9EC0 03Dokument62 SeitenExaminers' Report June 2017: GCE Economics A 9EC0 03nanami janinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blackout 30Dokument4 SeitenBlackout 30amitv091Noch keine Bewertungen

- Icelandic Line of WorkDokument22 SeitenIcelandic Line of Workfridjon6928Noch keine Bewertungen

- Compressors system and residue box drawingDokument1 SeiteCompressors system and residue box drawingjerson flores rosalesNoch keine Bewertungen