Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

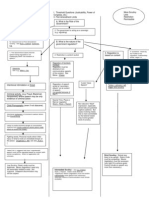

Environmental Law Outline

Hochgeladen von

Lillian JenksOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Environmental Law Outline

Hochgeladen von

Lillian JenksCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

I. ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES Environmental Problems, Environmental Justice and the Rationale for Collective Action Read (1) pp.

. 1-23 and 26-31 in the casebook NEPA 101, pp. 973-974 in the Statutory and Case Supplement pp. 1-2 of the Statutory and Case Supplement, and Info from slides EPA Definition of Environmental Justice: o Environmental justice: The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies. o Fair treatment: No group of people, including racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic group should bear a disproportionate share of the negative consequences resulting from industrial, municipal, and commercial operations or the execution of federal, state, local and tribal programs and policies. Executive Order 12898 (p.19) o 1-101: Agency Responsibilities o 1-102: Creation of Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice o 1-103: Development of Agency Strategies o 2-2: Federal Agency Responsibilities for Federal Programs o 6-609: Judicial Review History of the Environmental Justice Movement o 1979 first lawsuit challenging dump siting on civil rights grounds o 1982: Warren County, N.C. PCB landfill protests o 1983: GAO Study on Hazardous Waste Sites o 1987: UCC Commission for Racial Justice Report o 1991: First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit o 1992: National Law Journal enforcement study In re Louisiana Energy Services (1997) (p.20) Stage of Screening Process Number of Sites Under Percentage of Affected Consideration Population African-American 1 78 28.35% 2 37 36.78% 3 6 64.74% 4 1 97.1% Bob Kuehns Taxonomy of Environmental Justice o Distributive Justice: fairness in the distribution of benefits and burdens o Procedural Justice: fairness in procedures by which policy decisions are made o Corrective Justice: correcting for past injustices o Social Justice: expanding the concept of environmental justice to embrace larger inequities in society

Cost-benefit Analysis, Ecosystem Services and the Tragedy of the Commons. Read pp. 31-43, and 49-60 in the casebook. From slides Ethyl Corporation v. EPA (D.C. Cir. 1976) o Where a statute is precautionary in nature, the evidence difficult to come by, uncertain, or conflicting because it is on the frontiers of scientific knowledge, the regulations designed to protect public health, and the decision that of an expert administrator, we will not demand rigorous step-by-step proof of cause and effect. Such proof may be impossible to obtain if the precautionary purpose of the statute is to e served. II. ENVIRONMENTAL LAW: A STRUCTURAL OVERVIEW The Common Law Roots of Environmental Law: Private and Public Nuisance. Read pp. 61-88 in the casebook. From slides The Common Law Roots of U.S. Environmental Law o Aldreds Case (1611) (p.65): even nontrespassory invasions can be actionable as nuisances o Tenant v. Goldwin (1702) (p.65): sic utere principle o Bamford v. Turnley (1862) (p.65): overrules Hold v. Barlow (1856) to hold that the lawfulness of an activity is no defense to nuisance liability o St. Helens Smelting Co. v. Tipping (1865) (p.66): copper smelter held liable for damage to trees and crops o Sturges v. Bridgman (1879): nuisance liability depends on the character of the neighborhood Baltimore & Potomac R.R. Co. v. Fifth Baptist Church (1883: There are many lawful and necessary occupations which, by the odors they engender or the noise they create, are nuisances when carried on in the heart of a city No permission given to conduct such an occupation within the limits of a city would exempt the parties from liability for damages occasioned to others, however carefully they might conduct their business. What remedy should courts impose for private nuisances? o Smith v. Staso Milling (2nd Cir. 1927): court enjoins some activities, but not others o The Coase Theorum and Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co. (NY 1970): imposition of a conditional injunction Interstate Public Nuisance Cases in the Supreme Court o Missouri v. Illinois (1906) (p.77) o Georgia v. Tennessee Copper (1907) o New York v. New Jersey (1921) o Wisconsin v. Illinois (1929) o New Jersey v. City of New York (1931) o Illinois v. City of Milwaukee (1972) & City of Milwaukee v. Illinois (1981 Lessons from the History of the Ducktown Litigation (Georgia v. Tennessee Copper) o The Supreme Court recognized that states have a right to protect their citizens from substantial harm caused by pollution originating in another state.

Courts were reluctant to shut down economically important enterprises, but the threat of doing so created incentives for the development of improved technology to control pollution o The Court established a kind of equitable remedy requiring the smelter to use the best available control technology to control transboundary emissions Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co. (1907) Facts: Copper smelter in Tennessee was spewing pollution across state lines into Georgia. Holding: A state has an interest in the earth and air within its domain. o

The Rise of the Regulatory State, Environmental Federalism, Environmental Legislation and Preemption of Federal Common Law. Read (1) pp. 88-104 in the casebook Environmental Legislation in Historical Perspective on pp. xii-xv of the Statutory and Case Supplement, American Electric Power v. Connecticut on pp. 1123-1128 in the Statutory and Case Supplement. Slides Six Stages in History of U.S. Environmental Law o 1. Pre 1945: Common Law and Conservation Eras o 2. 1945-1962: Federal Assistance to States o 3. 1962-1970: Modern Environmental Movement o 4. 1970-1980: Erecting Regulatory Infrastructure o 5. 1980-1990: Improving regulatory Strategies o 6. 1991-2009: Reinvention and Legislative Gridlock Federal Environmental Legislation o National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)-1970 o Clean Air Act (CAA)- 1970 o Clean Water Act (CWA)- 1972 o Federal Insecticide, Fungicide & Rodenticide Act (FIFRA)- 1972 o Endangered Species Act (ESA)- 1973 o Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA)- 1974 o Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA)- 1976 o Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) 1976 o Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liabilit Act (CERCLA)- 1980 o Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA)- 1986 o Oil Pollution Act (OPA)- 1990 Important Features of the Federal Environmental Laws o The laws generally seek to establish comprehensive, national regulatory programs o They generally authorize federal agencies to set national standards to be implemented by states through delegated authority. o They generally authorize citizen suits against: (a) agencies for failure to perform mandatory duties and (b) violators of the environmental laws

o The laws employ a wide spectrum of approaches to regulation Illinois v. City of Milwaukee (p.87) o Facts: Illinois seeks to sue four Wisconsin cities and Milwaukee City & Count Sewearge Commission for discharging 200 million gallons of raw or barely treated sewage into Lake Michigan daily. o Milwaukee I Decision (1972): Court refuses Illinois leave to file a bill of complaint. However, Justice Douglas said, It may happen that new federal laws and new federal regulations may in time preempt the field of federal common law of nuisance. [CWA was enacted in following October] o Milwaukee II (1981): International Paper v. Ouellette (1987) (p.101) o Facts: Post Milwaukee II Supreme Court Decisions o Middlesex County Sewerage Authority v. National Sea Clammers Assn (1981): neither CWA nor Ocean Dumping Act create implied private right of action for damages. Federal common law of nuisance fully preempted for water pollution. o Exxon Shipping Co. v. Baker (2008): CWA does not preempt private claims for punitive damages for water pollution caused by reckless conduct. Connecticut v. American Electric Power o Facts: Eight states, NYC, and land conservation groups filed suit against four electric power companies and the TVA (the largest sources of GHG). The lawsuit alleged that the utility companies, which operate facilities in 21 states, are a public nuisance because their carbon-dioxide emissions contribute to global warming. The companies argue that only the ePA can set emissions standards. o Trial Court Holding (S.D.N.Y. 2005): Trial court dismisses common law nuisance action over GHG emissions as a nonjusticiable political question o 2nd Circuit Holding (2009): It is not a political question, plaintiffs have standing to sue, and the suit is not preempted by the Clean Air Act. o Supreme Court Holding (2010): Reversed. The Clean Air Act and the EPA action the act authorizes displace any federal common-law right to seek abatement of CO2 emissions from fossil fuel fired power plants. Comer v. Murphy Oil, USA (5th Cir. 2009) o Facts: Action against oil companies arguing that their contribution to climate change increased Hurricane Katrina damage. o Holdings: Not a political question, state law action not preempted by federal law, plaintiffs have standing to sue Native Village of Kivalina v. ExxonMobil Corp. (N.D. Cal. 2009) o Facts: Residents of small coastal village in Alaska seek $400 million in damages from 24 oil companies and powerplants due to climate change. o Holding: Court dismisses the case as nonjusticiable political question. State Standing, Environmental Federalism, and Forms of Collective Action. Read (1) pp. 104-119, 125-139 in the casebook, (2) Oil Pollution Act 1002(a) & (b) on p. 916 of the Statutory and Case Supplement, and (3) Oil Pollution Act 1004(a) on p. 919 of the Statutory and Case Supplement. Slides

Article III 2 Case or Controversy Requirement o The Judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under the Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party. Standing Requirements: o I. Constitutional Elements 1. Actual or Threatened Injury-in-Fact 2. Traceable to the Challenged Action 3. Redressable by Judicial Action o II. Prudential Restrictions 1. Prohibition of Third-Party Standing 2. Generalized Grievances (taxpayer) 3. Zone of Interest Requirement Evolution of Injury Concept of Standing Doctrine o Initial focus was on common law notions of legal injury to regulated industries o New questions raised by enactment in 1960s and 1970s of regulatory statutes to protect more diffuse interest of consumers, environment o Sierra Club v. Morton (1972): aesthetic injury to persons who alleged an interest in the subject matter is sufficient, as long as there is close enough connection between person and allegedly harmful act. Should trees have standing? o Yes, according to William O. Douglas Massachusetts v. EPA o Standing issues: Actual or threatened injury-in-fact (harm to public health, coastal resources, water supplies, agriculture and ecosystem)- is it sufficiently imminent? Traceable to the challenged action- are defendants emissions of GHGs a significant contributing cause to climate change? Redressability- can judicial action redress the harm plaintiffs allege? Is this a generalized grievance that affects everyone equally and thus precludes standing? o Justice Roberts Dissenting Opinion: Three Models of Federal-State Relations in Environmental Law o Federal government supplies only financial assistance while encouraging states to regulate- old approach, now largely confined to land use issues o Cooperative federalism (federal agency sets standards but states may qualify to issue and enforce permits subject to federal supervision)- predominant approach o Preemption of state standards by federal law- rare in federal environmental law (e.g., mobile source provisions of CAA, products regulated under TSCA and FIFRA pesticide labeling) Constitutional Authority for Federal Regulation o Can the DSA constitutionally prohibit private parties from harming the endangered Delhi Sands Flower-Loving Fly which is found only in two California counties?

Does it depend on what activity harms the fly? Construction of a hospital? Children riding dirt bikes?

III. PREVENTING HARM IN THE FACE OF UNCERTAINTY (started on class 6) I. Risk Regulation in the Face of Uncertainty: How Precautionary Should Regulatory Policy? a. Principle: We are always better off when we prevent harm instead of compensating afterwards, but we still need reliable predictors that something is harmful b. Before an agency or court is authorized to regulate a substance a threshold finding must be made that relates to the harmful potential of the substance or product to be regulated i. Ethyl Corp established that there are two variables: magnitude of harm and probability of harm occurring ii. Can be satisfied by high probability of lesser harm or lower probability of a greater harm c. importance of the burden of proof i. Shifting the burden of proof to the polluters once a reasonable risk threshold has been passed

Reserve Mining Company v. EPA (8th Cir. 1975) (p.185) Facts: Large mining plant was dumping asbestos fibers into Lake Superior. Plaintiffs tried to shut down the operation even though they did not know how the asbestos fibers caused harm when consumed rather than inhaled (multiple tests had been inconclusive). Holding: The plant needs to stop dumping, but not immediately. Engaged in a balancing test: based on the record, the probability of danger is low. However, if the hypothesis is correct, the health consequences would be huge. There is also major harm in closing down a major economic center. Therefore, the company should be given time to figure out a new disposal method. Ethyl Corp. v. EPA (D.C. Cir. 1976) Facts: EPA decided that lead in gasoline presented a substantial risk of harm and ordered reductions in the lad content of gasoline. Decision was based on several suggestive but inconclusive studies. Lead manufacturers claimed the statute required EPA to have proof of actual harm before it could order limits. Holding: Where a statute is precautionary in nature (like CAA), the evidence difficult to come by, uncertain or conflicting ecause it is on the frontiers of scientific knowledge, the regulations designed to protect the public health, and the decision that of an expert administrator, the court will not demand rigorous step-by-step proof of cause and effect. If the Administrators conclusions are rationally justified he may engage in a risk assessment that, if rational, will form the basis for healthreglated regulations under the will endanger language of section 211. II. Statutory Authority for Regulating Risks a. Complex array of statutory authorities address risks presented by toxic chemicals i. TSCA: gives EPA authority over any chemical substance or mixture (other than regulated by FIFRA of FDA)

III.

ii. FIFRA: governs EPA regulation of pesticides iii. SDWA: contaminants in public drinking water systems iv. CAA: hazardous air pollutants v. CWA: toxic water pollutants b. Differ in extent to which they require review or approval prior to manufacture or use of substances i. FDCA: approval of marketing ii. TSCA: EPA must be notified 90 days prior to manufacture of a new chemical or the application of an old chemical to a significant new use iii. Standard setting laws: require agencies to establish standards limiting toxic emissions, controlling worker exposure to toxics, or mandating warning labels on products 1. OSHA, SDWA, TSCA, CAA and CWA c. How safe is safe under the statutes: i. Risk-benefit balancing statutes: require that regulators balance the threat to public health against the cost of regulation when setting regulatory standards 1. TSCA, FIFRA ii. Feasibility-limited standards (subset of Technology- based standards): direct that threats to health be regulated as stringently as feasible 1. OSHA, SDWA iii. Health-based statutes: standards be based exclusively on concerns for protecting public health 1. NAAQS of CAA, FDCA d. Statutes differ in amount and kind of evidence that must be hsown before a substance can be regulated and in the type of controls that they authorize regulators to impose i. Outright prohibitions on manufacture or use of certain chemicals (TSCA, FIFRA, FDCA) ii. Authorize establishment of emission standards or ambient concentration limits (CAA, CWA, OSHA) iii. Restrictions on use and labeling, warning, or reporting requirements (TSCA) iv. Table on p.245 Risk-Benefit Balancing Approaches a. Quantitative risk assessments (QRA) are, to the maximum extent possible, used to evaluate proposed rules to reduce exposure to toxic substances i. QRA anticipates adverse health effects and environmental effects in terms of their dollar values 1. Very controversial and difficult to do ii. Problems and uncertainties 1. Uncertaincies of data 2. Necessity of making assumptions liking data to policy-related conclusions 3. Decision making on the frontiers of science

iii. Criticism of QRA 1. Very expensive to do 2. Information- starved 3. Feature manipulation of data 4. Are impacted by political pressure 5. Produce little abatement b. Example: Toxic Substances Control Act i. Grants EPA broad authority to regulate the manufacture, processing, distribution, use, or disposal of any chemical substance ona finding that there is a reasonable basis to conclude that such an activity presents or wil present an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment ii. In determining whether a substance poses an unreasonable risk, TSCA explicitly requires EPA to make findings for benefits of various uses of the substance, availability of substitutes for it, and reasonably ascertainable economic consequences of regulation iii. EPA must regulate to the extent necessary to protect adequately against such risk using the least burdensome requirements iv. QRAs are routine v. Principal Provisions (p.248) c. EPAs effort to ban asbestos under 6 of TSCA i. EPA announcement (1989) 1. Lay out all the risks of asbestos and conclude that it is an unreasonable risk to human health 2. Substitutes exist, and the rule includes an exemption for instances in which technology hasnt advanced sufficiently by the time of a ban to produce substitutes ii. Corrosion Proof Fittings v. EPA (5th Cir. 1991): A total ban on asbestos did not consider less costly alternatives Read (1) pp. 181-198 & 243-252 in the casebook, (2) 211(c)(1)&(2) of the Clean Air Act on p. 652 of the Statutory and Case Supplement. How Safe Is "Safe"?: Cost/Benefit Balancing and the Asbestos Ban and Regulation by Revelation. (1) pp. 252-264, 311-319 & 323-331 in the casebook and (2) 6(a)&(c)(1) of the Toxic Substances Control Act, on pp. 86-87 of the Statutory and Case Supplement. IV. REGULATING WASTE MANAGEMENT I. History of Waste Disposal a. Early Stage: Local responsibility i. Most wastes were dumped without treatment wherever it was convenient. Waste management was considered a local responsibility ii. Government did not consider the environmental consequences of toxic waste disposal iii. Many assumed nature could assimilate the wastes without harm b. Congress enacted regulatory legislation in the 1970s:

II.

Clean Air Act (1970) Clean Water Act (1972) Ocean Dumping Act (1974) Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (1976) 1. Added Subtitle C: provided for comprehensive regulatory program to ensure that hazardous waste was managed from cradle to grave v. Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liablity Act (1980) 1. This is a misnomer because there was no victim compensation scheme vi. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (1986) Federal Laws regulating waste management a. Ocean Dumping Act: bans dumping of waste in the ocean without a permit, later amended to ban ocean garbage dumping b. RCRA: requires EPA to regulate hazardous waste management from cradle to grave c. CERCLA: creates superfund and procedures for cleaning up dumpsites, imposes strict liability for cleanup costs d. Pollution Prevention Act: establishes preferred hierarchy of waste management practices i. 1. Source reduction: design production processes to prevent creation of waste in the first place ii. 2. Recycling: to the extent you can prevent creation of waste, recycle it iii. 3. Treatment: ensure it wont cause any long term environmental hazard iv. 4. Disposal: last option Waste Managemen t Objective Protect and improve surface water quality Pollutants/waste s Covered Regulatory Approach Basis for Controls Primary Transfers to another Medium Sludge to land; air emissions from treatment plant and sludge incineration

i. ii. iii. iv.

Statute

Clean Water Act

All discharges to surface waters, including 126 priority toxic pollutants.

Performanc e standards (emissions limits); ambient standards

Technology with healthbased backup

Marine Protection Research and Sanctuaries Act Safe Drinking Water Act

Limit dumping into ocean

All wastes except oil and sewage in the ocean

Protect public drinking

Contaminants found in drinking

Use restrictions (prohibited unless done with permit) Ambient standards,

Balancing, with healthbased backup Technology

supply

Clean Air Act

Protect and improve air quality

water and wastes injected into deep wells All emissions to air

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

Comprehensiv e Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act Surface mining control and reclamation Act Nuclear Waste Policy

Control hazardous and solid wastes; encourage waste reduction and recycling Cleanup of abandoned hazardous waste sites; emergency response Control pollution from surface coal mines Control disposal of high-level radioactive wastes Control disposal of low-level radioactive wastes Manage uranium mill tailings Prevent unreasonable

Hazardous and solid wastes

design and performanc e standards Ambient standards; performanc e standards (emissions limits) Use restrictions, design and performanc e standards; information disclosure Performanc e and design standards

Health: technology

Sludge and incinerator residues to land

Health

Air through incineration; water through sewage treatment plants Air through volatilization , incineration, and dust

Release or threatened release of hazardous substance

Health, with costeffectiveness constraint

Surface coal mining wastes

Performanc e standards

Health (or environment ) Health (or environment )

Releases to water

Commercial highlevel radioactive waste

Use restrictions

Low level radioactive waste policy act Uranium mill tailings radiation control Toxic substances

Cmmercial highlevel radioactive waste

Use restrictions

Health (or environment )

Uranium mill tailings

Performanc e standards

Health (or environment

Air from dust

Wastes from production or use

Use restrictions

Balancing

control act

risk from chemical substances

of industrial chemical substances

III.

The Resource Conservation & Recovery Act a. Main point: RCRA is largely regulatory statute because EPA can tell generators, treatment, or transporters of hazardous waste how to treat it b. Jurisdictional term: solid waste (1004(27)) and hazardous waste (1004(5)) i. Solid Waste: defined in 1004(27) to included any garbage, refuse, sludge from a waste treatment plant, water supply treatment plant, or air pollution control facility and other discarded material, including solid liquid, semisolid or contained gaseous material, resulting from industrial, commercial, mining and agricultural activities, and from community activities. ii. Hazardous Waste: 1. Listed waste: waste streams that are specifically listed as hazardous by EPA 2. Wastes that exhibit hazardous characteristics (toxicity, corrosivity, reactivity, and ignitability) 3. Mixture rule: wastes mixed with a listed waste 4. Derived-from rule: wastes derived from a listed waste 5. **Problem: it is usually left up to the producer to decide whether a waste was hazardous or not c. Overview i. Enacted in 1967 to prevent environmental damage from improper management of hazardous waste ii. Requires EPA to issue regulations identifying hazardous waste and governing management of it from cradle to grave iii. Bans export of hazardous waste unless the country receiving waste has consented or adopted treaty d. Structure i. Subtitle C: Hazardous Waste 1. 3001: Identification and listing of hazardous waste a. Can be from a waste stream that is specifically said to be hazardous (always a hazardous waste) b. Or that exhibits a characteristic of a hazardous waste (remains hazardous only so long as it exhibits toxicity, reactivity, corrosiveness or ignitability 2. 3002: Regulation of generators 3. 3003: Regulation of transporters 4. 3004: Regulation of treatment, storage and disposal of facilities (TSDs) 5. 3005: Permit requirement for TSDs ii. Subtitle D (4001-4010): applies to all non-hazardous solid waste (mostly municipal garbage)

1. 7002: Citizen suit provisions 2. 7003: gave EPA the authority to bring suit to halt imminent & substantial endangerment (many fewer suits today as a result of CERCLA) e. Initial Implementation of RCRA by EPA i. EPA found it extremely difficult to develop clear regulations identifying which wastes were hazardous. EPA issued its RCRA regulations only after the EDF brought a lawsuit ii. The initial regulations did not require most facilities handling hazardous waste to use new technology to control releases iii. EPA eventually realized that in all cases where wastes are dumped on land they eventually will leak out in ways that damage the environment iv. Amended in 1984 by banning land disposal of untreated hazardous waste and adding hammer provisions (incentivized industry to push for EPA regulations to avoid hammer provision) f. Note on gaseous waste: i. If something comes out of production as a gas (it is a gas in its natural state), it is subject to regulation under CAA, not RCRA ii. Solid waste cannot be gasified in order to bypass RCRA g. Recycled Materials i. AMC I: EPA exceeded its authority by including recycled materials in its definition of solid waste ii. AMC II: AMC I only applied to closed loop. Sludge stored in unlined surface impoundment could be regulated under RCRA when company said that at some point they intended to recycle it. iii. In 2008, EPA amended its regulations defining solid waste to create a generator controlled exclusion and a transfer based exclusion (if you transfer materials for recycling to someone else and you can show they are useful for recycling purposes, it is not subject to RCRA) h. Problems with RCRA program i. Difficulties in identifying hazardous waste (requirements for testing wastes to determine if they meet hazardous characteristics are vague) ii. Exemptions may leave many hazardous substances unregulated (household wastes, recycling, and wastes dumped in sewers are exempt) iii. Extent of regulation does not vary with the degree of hazard- either a waste is hazardous and its management is strictly regulated or it is not hazardous and it is largely unregulated i. Read (1) pp. 338-341 & 343-366 in the casebook 2) RCRA Legislative History Timeline and Outline of Principal Provisions of the Solid Waste Disposal Act on pp. 300-301 in the Statutory and Case Supplement, and (3) Solid Waste Disposal Act 1004(5) & (27), pp. 305-306 and 307 in the Statutory and Case Supplement. American Mining Congress v. EPA (D.C. Cir. 1987) (p.356)

Facts: EPA amended its definition of solid waste to include recycled materials. The definition did not include raw materials, but did include anything else. If it was a closed loop, where a material goes straight back into production process, it wont be regulated. However, if it sits around for a while it should be regulated because there is potential for danger. Holding: The court applied Chevron and found that the term solid waste is unambiguous. RCRA was enacted to deal with solid waste disposal, not ongoing manufacturing process. Therefore EPA exceeded its authority. Mikva Dissent: We should defer to the expert agency here. If EPA sees this as part of the problem, it should be dealt with. The plan of the producer to ultimately use the material has nothing to do with whether or not it is causing an environmental danger while stored.

CERCLA a. Basic principles i. Direct extension of common law principles of strict liability for abnormally dangerous activities ii. Modeled on Clean Water Acts oil spill liability program iii. The core of the act is its liability provisions and its authorization to EPA to spend monies from the Superfund for removal operations (short-term action to address immediate hazards) and for remediation operations (long-term solutions, including decontamination) iv. EPA is authorized to incur expenses respondingto imminent threats to health and the environment under removal authorites, but can only spend money on remediation for sites that it has placed on the National Priority List (104, 105) v. 105 instructs EPA to place at least 400 sites needing cleanup on the initial NPL and to prepare a National Contingency Plan for dealing with hazardous waste cleanup vi. state governments and federal authorities can engage in joint cleanup vii. EPA has the authority to order private parties to undertake actions to abate actual or potential releases of hazardous substances in order to prevent imminent and substantial endangerment. viii. Superfund 1. Originally funded through tax on chemical feedstocks and petroleum. Tax expired in 1995 and hasnt been reauthorizd. 2. Lack of new funds has been slowly starving program for funds for cleanups that are not paid for by potentially responsible parties b. Main purpose: to make spills or dumping of hazardous substances less likely through liability c. Principal Provisions 101. Definitions: the term hazardous substance is defined in 101(14); release is defined in section 101(22) 103. Notification Requirements : requires reporting of releases of hazardous substances to the National Response Center.

IV.

104. Response Authorities: authorizes the president to undertake removals or remedial actions consistent with the National Contingency Plan to respond to actual or potential releases of hazardous substances. 105. National Contingency Plan: requires establishment of a National Priorities List (NPL) of facilities presenting the greatest danger to health, welfare, or the environment based on a hazard ranking system (HRS) and requires revision of National Contingency Plan (NCP) 106. Abatement Orders: authorizes issuance of administrative orders requiring the abatement of actual or potential releases that may create imminent and substantial endangerment to health, welfare, or the environment. 107. Liability: imposes liability on (1) current owners and operators of facilities where hazardous substances are released or threatened to be released, (2) owners and operators of facilities at the time substances were disposed, (3) persons who arranged for disposal or treatment of such substances, and (4) persons who accepted such substances for transport for disposal or treatment. These parties are liable for: (a) all costs of removal or remedial action incurred by the federal government not inconsistent with the NCP, (b) any other necessary costs of response incurred by any person consistent with the NCP, (c) damages for injury to natural resources, and (d) costs for health assessments. Creates exemptions for innocent purchasers, bona fide prospective purchasers, and de micromis contributors. 111. Superfund: creates a Superfund which can be used to finance governmental response actions and to reimburse private parties for costs incurred in carrying out the NCP. 113. Judicial Review and Contribution: bars pre-enforcement judicial review of response actions and abatement orders, and authorizes private actions for contribution against potentially responsible parties. 116. Cleanup Schedules: establishes schedules for evaluating and listing sites on NPL, commencement of remedial investigation and feasibility studies (RI/FFs) and commencement of remedial action. 121. Cleanup Standards: establishes preference for remedial actions that permanently and significantly reduce the volume, toxicity, or mobility of hazardous substances and requires selection of remedial actions that are protective of health and the environment and cost-effective, using permanent solutions to the maximum extent practicable; requires cleanups to attain level of legally applicable or relevant and appropriate standard, requirement, criteria or limitation contained under any federal environmental law or more stringent state law. 122. Settlements: sets standards for settlements with potentially responsible parties. d. Liability Provisions i. Definition of Hazardous Substance 1. Very broadly defined 2. Includes just about every toxic substance other than petroleum -hazardous waste subject to regulation under subtitle C of RCRA, toxic water pollutants regulated under section 307 of the CWA, hazardous air pollutants under section 112 fo the CAA, imminently hazardous chemicals regulated under 7 of TSCA, substances other than oil that have been designated as hazardous of CWA, and additional substances as designated by EPA

3. Petroleum (including natural gas and crude oil) are specifically exempted [they are covered instead by 311 of CWA] 4. Also gives CERCLA jurisdiction over substances not listed in any categories of hazardous substances if it is a pollutant or contaminant which may present an imminent and substantial danger to the public health or welfare ii. Definition of Release 1. Any spilling, leaking, pumping, pouring, emitting, emptying, discharging, injecting, escaping, leaching, dumping, or disposing into the environment (including the abandonment or discarding of barrels, containers, and other closed receptacles containing any hazardous substance or pollutant or contaminant [101(22)] 2. Specifically exempts: a. Application of pesticides registered under FIFRA b. Exempts federally permitted releases (which includes discharges authorized by permits issued under CWA, RCRA, Ocean Dumping Act, SDWA, CAA, AEA and certain fluid injection practices for producing oil or natural gas. iii. Constitutional challenge: impermissible retroactive legislation iv. Responsible parties 1. Owners a. Innocent Purchaser? i. New York Shore Realty: owners who purchased after the time of disposal are still liable unless the realeases and threats of release were caused solely by the tenants or Shore took precautions against foreseeable acts ii. 1986: SARA (Superfund Amendments Reauthorization Act) created a defense for innocent land purchasers if they can establish that [response to fairness claims] 1. they did not have actual or constructive knowledge of the presence of hazardous substances at the time the land was acquired 2. they are govt entities acquiring the land through involuntary transfer 3. they acquired the land by inheritance or bequest iii. In determining whether purchaser satsifed all appropriate inquiry criteria, courts were originally supposed to consider: 1. Purchasers specialized knowledge or experience

2. Relationship of purchase price to value of uncontaminated property 3. Reasonably ascertainable information about the property 4. Obviousness of the likely presence of contamination 5. Ability to detect such contamination by inspection iv. EPA established final rule establishing standards and practices for AAI: 1. Purchasers need to retain services of an environmental professional a. Individual with training in conducting environmental audits b. EP must submit written report of findings 2. Interviews with past and present owners 3. Many other due diligence measures v. This exception is not necessarily available under state Superfund statutes vi. 2002: Congress created 107(r): exempts bona fine prospective purchasers from owner or operator liability if they satisfy all the requirements of 107(r) b. Passive Liability: Are owners who engage in no active conduct relating to disposal themselves but who owned the land at a time when wastes deposited on the land before their ownership continued to leak or spill onto the land? i. No: US v. CDMG: The words used to define dispoal are active; to acknowledge passive owner liability would vitiate innocent disposal purchaser defense ii. Yes: Nurad: not recognizing a passive owner would mean that an owner could avoid liability by standing idle while an environmental hazard resters on the property 2. Operators 3. Arrangers: 107(a)(3) a. any person who by contract, agreement, or otherwise arranged for dispoal or treatment, or arranged with a transporter for transport for dispoal or treatment, of hazardous substances owned or possessed by such person, by any other party or entity, at any facility or incineration

b. c.

d.

e.

vessel owned or operated by another party or entity and containing such hazardous substances Imposes liability on non-negligent generators of hazardous substances This creates a power incentive for such persons to ensure that wastes are managed carefully generators now must select treatment and disposal options and monitor their implementation with care Initially there was circuit split over arranger liability i. Aceto: Pesticide manufacturers shipped raw materials to Aidex, who mixed products and sold them. Manufacturers were liable for Aidex facility cleanup because they knew that spills of raw materials were an inherent part of the formulation process. ii. Governments case is satisfied once it has proved that 1. A generator shipped hazardous substances to the facility 2. Hazardous substances like those present in the generators waste were found at the facility 3. There had been a release of hazardous substances at the site iii. Detrex: arranged for implies intentional action, so a truck spill on the way to the facility doesnt count (they didnt hire the truckers to spill chemicals) iv. South Water Management Dist: totality of the circumstances approach v. 3rd Circuit: most important factors are: 1. ownership or possession 2. knowledge 3. control Supreme Court resolved issue to hold that an entity qualifies as an arranger when it takes intentional steps to dispose of a hazardous substance (Burlington Northern) i. Knowledge alone is insufficient to prove that an entity planned for the disposal, particularly when the disposal occurs as a peripheral result of the legitimate sale of an unused, useful product. ii. In order to quality as an arranger, Shell must have entered into the sale of D-D with the intention that at least a portion of the product be disposed

of during the transfer process by one or more of the methods described in the statute iii. Shells insistence that B&B improve their maintenance shows that they did not intend for such spills to occur f. Exemptions for arrangers: i. Superfund Recycling Equity Act: exempts arrangers and transporters who arrange for recycling of recyclable materials 1. Requires proving a number of conditions have been met, and is denied to anyone who had an objectively reasonable basis to believe that the materials would not be recycled ii. Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act: de micromis generators or transporters 1. People who contribute less than 110 gallons of liquid materials or 200 pounds of solid materials 2. Part of which must have occurred before April 1, 2001 3. Doesnt apply if President determines that the hazardous substances contributed significantly to the response costs or if person seeking to qualify for the exemption impeded the response action or committed a crime 4. SBLRBRA: 107(p) exempts homeowners, certain small businesses, and certain nonprofits from liability for generation of MSW iii. Arranger liability can attach to parties who do not have an active involvement in the timing, manner, or location of disposal. However, there must be some nexus between the potentially responsible party and the disposal of the hazardous substance that is premised upon the potentially liable partys conduct with respect to the disposal or transport of hazardous wastes. New York v. Shore Realty Corp. (2nd Cir. 1985) (p.402) Facts: Shore Realty bought a property that they knew was occupied by tenants who were illegally operating a waste storage facility. They argued that they were not liable under CERCLA because they

neither owned the site at the time of disposal nor caused the presence or the release of the hazardous waste. Claims they are not covered by 9607(a)(1) because that could not have been intended to cover all owners, because that would render the word owned in 9607(a)(2) redundant. Holding: 9607(a)(1) unambiguously imposes strict liability on the current owner of a facility from which there is a release or threat of release, without regard to causation. Accepting Shores argument would open a huge loophole (would allow the owner of a site to avoid liability by purchasing the site after the dumping had happened). Not covered by the affirmative defense in 9607(b)(3) because they were aware of the nature of the tenants activity. Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway Co. (2006) (p.421) Facts: Holding: Read (1) pp. 393-397, 401-408 & 418-428 in the casebook, (2) edited excerpt from General Electric Co. v. Jackson posted under Ch. 4 Updates on the casebook website (www.erlsp.com), (3) CERCLA Legislative History Timeline and Outline of Principal Provisions of CERCLA on pp. 402-403 in the Statutory and Case Supplement, and (4) 101(14), 101(22), 107(a)&(b), and 101(35) of CERCLA, on pp. 405-406, 408-409, 434435, and 410-411of the Statutory and Case Supplement.

V. AIR POLLUTION CONTROL I. Clean Air Act a. Major Provisions

TITLE I 108: Requires EPA to identify air pollutants anticipated to endanger public health or welfare and to publish air quality criteria. 109: requires EPA to adopt nationally uniform ambient air quality standards (NAAQSs) for criteria air pollutants 110: requires states to develop and submit to EPA for approval state implementation plans (SIPs) specifying measures to assure that air quality within each state meets the NAAQSs. 111: requires EPA to establish nationally uniform, technology-based standards for major new stationary sources of air pollution New Source Performance Standards (NSPSs) 112: mandates technology-based standards to reduce listed hazardous air emissions from major sources in designated industrial categories, with additional regulation possible if necessary to protect public health with an ample margin of safety. *This is a separate program for hazardous pollutants. For pollutants that are carcinogens, etc., EPA is to regulate not just to provide an adequate margin for safety, but for an ample margin for safety of human health. *at first EPA was nervous this was too stringent so they only regulated 6 things. But in 1990 Congress named 178 specific chemicals that will be deemed to be hazardous air pollutants to be dealt with by maximum achievable control technology. If, after applying MACT, there is still a 1 in 1 million risk, EPA decides whether to continue

Part C: specifies requirements to prevent significant determioration of air quality (PSD) for areas with air quality that exceeds the NAAQSs. Part D: specifies requirement for areas that fail to meet the NAAQS (nonattainment areas) TITLE II: requires EPA to establish nationally uniform emissions standards for automobiles and light trucks that manufacturers must meet by strict deadlines. TITLE III 304: Authorizes citizen suits against violators of emissions standards and against the EPA administrator for failure to perform nondiscretionary duties 307: Authorizes judicial review of nationally applicable EPA actions exclusively in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit TITLE IV: creates a system of marketable allowances for sulfur dioxide emissions from power plants and major industrial sources to reduce acid precipitation TITLE V: requires permits for all major industrial sources with state administration and federal oversight. TITLE VI: establishes a program for controlling substances that contribute to depletion of stratospheric ozone. b. History of Clean Air Act i. 1970: Clean Air Act was the first of the regulatory statutes ii. targeted mobile sources 1. required 90% reduction in pollution from mobile sources within 5 years 2. forced radical technological innovation 3. possible because the political situation was different: both parties were trying to prove that they were greener iii. Problems with initial implementation: 1. It said nothing about what to do in areas where the air quality was pristine enough so that it already complied [Sierra Club argued that EPA had a duty to slow down deterioration in pristine areas iv. Clean Air Amendments of 1977 1. Wrote into the Act the way in which EPA was implementing 2. Areas of the country which are in attainment are classified v. Problems with CAA after 1977 1. Grandfathering in existing sources was a premise of CAA. But then utilities had an incentive to operate old sources for as long as possible and tried to update through routine maintenance vi. Provisions of the 1990 Amendments: 1. Title IV: created cap and trade program for SO2 that cause acid rain that gave initial allowances c. State-Federal Roles i. Federal: EPA establishes national ambient air quality standards for criteria pollutants ii. State governments then decide how the numerous existing sources within their jurisdictions whose emissions contribute to the ambient levels of these

pollutants ought to be controlled in order to meet those NAAQSs for their jurisdictions 1. Each states set of regulations to meet the NAAQSs is called its state implementation plan (SIP) iii. SIPs must be submitted to EPA, which approves their adequacy to accomplish statutory requirements iv. If state does not prepare an SIP that meets the requirements fo the act, EPA must prepare a federal implementation plan (FIP) that ensures the NAAQSs will be met v. SIP must avoid interfering with the efforts of other states to achieve compliance with NAAQSs d. What is an air pollutant that may be regulated under the Clean Air Act? i. Statutory definition: any physical, chemical, biological, radioactive substance or material which is emitted into or otherwise enters the ambient air. ii. Mass v. EPA: 1. EPA argued it did not have the authority to regulate GHGs because they are not air pollutants. Congress is aware of climate change: if they had wanted EPA to regulate GHG they would have said so in the 1990 amendments (largely based on FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp.) a. Supreme Court rejects EPAs argument that they do not have authority to regulate GHG i. This is not FDA v. Brown & Williamson because they would not have to ban the product entirely, like they would have had to with tobacco ii. EPA regulation was not preempted by DOTs mandate to deal with tailpipe emissions 2. EPAs second argument: even if they could regulate it, they wont because of judgment that this would not be e. Nonmobile sources i. Up to the federal government ii. All state authority to regulate mobile sources is preempted by federal statute, except California iii. States can create Transportation Control Plans (TCPs) f. Fuel Content i. EPA authorized to restrict or prohibit the use of any fuel additive that causes, or contributes, to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger the public health or welfare (211(c)) g. Alternative Vehicles i. California has Zero Emission Vehicle standards hasnt created ZEV but have been technology forcing ii. Other states can adopt CAs program (otherwise preempted by federal statute) but must adopt any revisions CA makes

Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) (p.509) Facts: EPA argued they did not have the authority to regulate GHG and if they did they declined to do so. Holding: The broad definition of air pollutant forecloses the EPAs reading- they have authority. And they can only decline to exercise authority if they make a judgment on scientific endangerment, not just because of political strategy (cannot be divorced from statutory text). Read (1) pp. 499-528 in the casebook and (2) Clean Air Act Legislative History Timeline and Outline of the Principal Provisions of the Clean Air Act on pp. 504-507 of the Statutory and Case Supplement. National Ambient Air Quality Standards a. Establishing NAAQS i. 109: requires the EPA administrator to set primary NAAQSs at the level which, in the judgment of the Administrator, based on the ambient air quality criteria and allowing an adequate margin of safety, are requisite to protect the public health ii. supposed to accurately reflect the latest scientific knowledge useful in indicating the kind and extent of all identifiable effects on public health or welfare which may be expected from the presence of such pollutant in the ambient air iii. Early problems establishing NAAQS 1. Scientific data lacking or inconsistent 2. Even as we do more studies, experts disagree on meanings 3. Questions left open by the text: a. What is a health effect? any change in blood chemistry, or only hanges proved to have an adverse effect on bodily functions b. What constitutes adverse? c. What population should be used as the measure of effects? 4. Regulatory burden in establishing NAAQSs is so demanding that EPA has incentives to avoid making frequent changes or to promulgate new standards a. Whenever EPA promulgates or revises an ambient standard, every SIP must be amended and reviewed iv. Current NAAQSs on p.553 1. Primary Standards: to protect the public health allowing an adequate margin of safety 2. Secondary Standards: to protect the public welfare from any known or anticipated adverse effects of air pollution 3. Concentrations of pollutants specified by the standards are expressed in terms of averages over different periods of time

II.

v. CAA requires NAAQS to be set based on public health considerations alone, without balancing those considerations against the costs of meeting them 1. Lead Industries Assn: The Administrator should take precautionary measures and is not limited to setting limits that are supported by medical consensus. As long as there is evidence in the record which substantiates Administrators conclusions about the health effects on which the standards were based, she can err on the side of caution. vi. Economic criticism: justifying uniform standards as efficient would have to assume that the costs of a given level of pollution and a given level of control are the same across the nation, but this is clearly not the case. b. Revising NAAQSs i. EPA is required to review and revise its air quality criteria and the NAAQSs at five year intervals [109(d)] ii. EDF v. Thomas: court cannot dictate to EPA whether or how the NAAQSs should be resvised. But the Administrator must make some decision regarding the reviewion of the NAAQSs that would be subject to judicial review. By publishing revised creitera documents [about sulfur oxide], EPA triggered a duty on its part to address and decide whether and what kind of revision is necessary. iii. EPA has been reluctant to revise NAAQSs because of the enormous administrative burden such revisions would generate 1. State must prepare a revised SIP and then submit it for EPA approval iv. EPA usually cites to scientific uncertainty in declining to revise NAAQSs v. How much protection should NAAQSs afford sensitive populations? 1. LIA: air quality standards must also protect individuals who are particularly sensitive to the effects of the population [asthmatics, emphysematics] Lead Industries Association v. EPA (D.C. Cir. 1980) (p.554) Facts: EPA wanted to set lead limits lower than what was currently known to be the trigger for adverse health affects. Holding: This is permissible because Congress directed the Administrator to allow an adequate margin of safety. The Administrator not limited to acting to prevent health effects that are known to be clearly harmful. The Administrator is entitled to err on the side of caution as long as there is evidence in the record which substantiates his conclusions about the health effects on which the standards were based. Whitman v. American Trucking Assns (2001) (p.564) Holding: The text of 109(b) unambiguously bars cost considerations from the NAAQS-setting process. Read (1) pp. 546-573 in the casebook and (2) Clean Air Act 108 & 109 on pp. 522-524 of the Statutory and Case Supplement.

VI. CONTROL OF WATER POLLUTION I. Introduction to the Clean Water Act and the Scope of Federal Jurisdiction. a. Statutory Authorities i. Clean Water Act: prohibits all unpermitted discharges into the waters of the United States of pollutants from point sources, imposes effluent limitations on dischargers, and requires statewide planning for control of pollution from nonpoint sources. ii. Ocean Dumping Act: prohibits all dumping of wastes in the ocean except where permits are issued by EPA (for non-dredged materials) or by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (for dredged materials). Permits are conditioned on a showing that the dumping will not unreasonably degrade the environment iii. Coastal Zone Management Act: provides financial assistance to encourage states to adopt federally approved coastal management plans; requires federal actions in coastal areas to be consistent with state programs. Amended in 1990 to require states to adopt programs to control nonpoint sources of coastal water pollution. iv. Oil Pollution Act: Makes owners of vessels discharging oil liable for costs of cleanup; establishes an Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund to pay response costs; and imposes minimum design standards to prevent spills by vessels operating in U.S. waters. v. Safe Drinking Water Act: regulates the quality of drinking water supplied by public water systems; establishes a permit program regulating the underground injection of hazardous waste, and restricts activities that threaten sole-source aquifers. 1. Cheney loophole: defines underground injection by excluding hydraulic fracturing activities [hydraulic fracturing cannot be regulated by existing federal environmental laws] vi. RCRA and CERCLA: considerable relevance for groundwater protection and remediation b. Predecessor to CWA: Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1954 (gave money to the states to deal with water pollution) c. Goals of the CWA i. Very ambitious goals ii. Two permit programs: 1. 402: Discharges of pollutants in navigable waters 2. 404: governs dredged or fill material iii. Anytime a federal permit is required for a project, the Federal government asks the state to certify water quality d. The structure of the CWA 101 Goals: Declares national goals of fishable/swimmable waters by 1983 and the elimination of pollutant discharges into navigable waters by 1985. 301 Effluent Limitation: Prohibits the discharge of any pollutant (defined in 502(12) as the addition of any pollutant (as defined in 502(12) as the addition of any pollutant to navigable waters from any point source or to the waters of the ocean or contiguous zone from any point source other than a vessel) except those made in compliance with the terms of the Act, including the permit requirements of section 402. Imposes multi-tiered effluent limitations on existing sources whose stringency and timing depends on the nature of the pollutant discharged and whether the outfall is directed to a water body or a publicly owned treatment works (POTW)

302 Water Quality Related Effluent Limitations: Authorizes the imposition of more stringent effluent limitations when necessary to prevent interference with the attainment or maintenance of desired water quality. 303 Water Quality Standards & TMDLs: Requires states and tribes to adopt and to review triennially water quality criteria and standards subject to EPA approval, to identify waters where effluent limits are insufficient to achieve such standards, and to establish total maximum daily loads (TMDLs) of pollutants for such waters. 304 Federal Water Quality Criteria and Guidelines: Requires EPA to adopt water quality criteria and guidelines for effluent limitations pretreatment programs, and administration of the NPDES permit program. 306 New Source Performance Standards: Requires EPA to promulgate new source performance standards reflecting best demonstrated control technology. 307 Toxic and Pretreatment Effluent Standards: Requires dischargers of toxic pollutants to meet effluent limits reflecting the best available technology economically achievable. Requires EPA to establish pretreatment standards to prevent discharges from interfering with POTWs. 309 Enforcement Authorities: Authorizes compliance orders and administrative, civil, and criminal penalties for violations of the Act. 319 Nonpoint Source Management Programs: Requires states and tribes to identify waters that cannot meet water quality standards due to nonpoint sources, identify the activities responsible for the problem, and prepare management plans identifying controls and programs for specific sources. 401 State Water Quality Certification: Requires applicants for federal licenses or permits that may result in a discharge into navigable water to obtain a certification from the state in which the discharge will occur that it will comply with various provisions of the Act. 402 NPDES Permit Program: Establishes a national permit program, the national pollution discharge elimination system (NPDES), that may be administered by EPA or by states or Indian tribes under delegated authority from EPA. 404 Dredge and Fill Operations: Requires a permit from the Army Corps of Engineers for the disposal of dredged or fill material into navigable waters with the concurrence of EPA unless associated with normal farming. 505 Citizen Suits: Authorizes citizen suits against any person who violates an effluent standard or order, or against EPA for failure to perform a nondiscretionary duty. 509 Judicial Review: Authorizes judicial review of certain EPA rulemaking actions in the U.S. Court of Appeals. 518 Indian Tribes: Authorizes EPA to traet Indian tribes as states for purposes of the Act for tribes that have governing bodies carrying out substantial governmental duties and powers. e. Scope of Federal Authority to Regulate Water Pollution i. Jurisdictional term: navigable waters (defined in 502(7) as the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas. ii. Courts are split about whether EPA can regulate discharges to groundwater or deep well injection of wastes in order to protect surface waters. Definitely not when wells are not connected to surface waters. EPA has declined to assert jurisdiction. iii. Navigable Waters 1. Riverside Bayview: should be understood broadly to effectuate the purposes of the act 2. EPA and Corps definition:

All other waters such as intrastate lakes, rivers, streams (including intermittent streams), mudflats, sandflats, wetlands, sloughs, prairie potholes, wet meadows, playa lakes, or natural ponds, the use, degradation or destruction of which could affect interstate or foreign commerce including any such waters: i. Which are or could be used by interstate or foreign travelers for recreational or other purposes; or ii. From which fish or shellfish are or could be taken and sold in interstate or foreign commerce; or iii. Which are or could be used for industrial purposes by industries in interstate commerce b. After SWANCC, EPA and ACE issued joint memo that SWANCC, squarely eliminates CWA jurisdiction over isolated waters that are intrastate and nonnavigable, where the sole basis for asserting federal jurisdiction is the actual or potential use of the waters as habitat for migratory birds that cross state lines in their migrations. 3. Significant Nexus test: To constitute navigable waters under the Act, a water or wetland must possess a significant nexus to waters that are or were navigable in fact or that could reasonably be so made United States v. Riverside Bayview Homes, Inc. (1985) (p.653) Facts: Respondent wanted to fill its wetlands that are continguous to a lake. Holding: Applied Chevron deference and found that Army Corps of Engineers had 404(a) jurisdiction over wetlands that actually abutted on a navigable waterway. The word navigable is of limited import and Congress evidenced its intent to regulate at least some waters what would not be deemed navigable under the classical understanding of that term. The significant nexus between the wetlands and the navigable waters made it permissible to include wetlands that abutted on navigable waters in the statutory term navigable waters. Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (2001) (p.658) Facts: Abandoned sand and gravel pit turned into two ponds that migratory birds visited. Army Corps of Engineers asserted jurisdiction when owners wanted to turn it into a landfill. They relied on the Migratory Bird Rule that they had promulgated. Holding: Isolated ponds wholly located within Illinois do not fall under 404(a)s definition of navigable waters because they serve as a habitat for migratory birds. This would give the term navigable no effect whatsoever. There is no Chevron deference because there is no ambiguity: Congress did not intend what ACoE did. Rapanos v. United States (2006) (p.661) Holding: The phrase the waters of the United States includes only those relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water forming geographic features that are described in ordinary parlance s streams oceans, rivers and lakes. The phrase does not include channels through which water flows intermittently or ephemerally, or channels that periodically provide drainage for rainfall. Only those wetlands with a continuous surface connection to bodies that are waters of the United States in their own right, so that there is no clear demarcation between waters and wetlands, are adjacent to such waters and covered by the Act. Wetlands that only have an intermittent hydrologic connection to waters of the US do not satisfy the significant nexus test.

a.

Kennedy Concurrence: The plurality and dissent did not apply the significant nexus test. The case should be remanded for proper consideration of the nexus requirement. Wetlands possess the requisite nexus if they, either alone or in combination with similarly situated lands in the region, significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of other covered waters more readily understood as navigable. d. Statutory references: Clean Water Act Legislative History Timeline and Principal Provisions of the Clean Water Act on pp. 762-763 in the Statutory and Case Supplement, and Clean Water Act 301(a), 404(a) & 502(6)&(7) on pages 818, 886 and 896 of the Statutory and Case Supplement. II. Regulation of Point Sources of Water Pollution, Effluent Limits, Water Quality Standards and Total Maximum Daily Loadings. a. 301(a): the discharge of any pollutant by any person shall be unlawful except in compliance with certain sections of the Act, including the permit requirements of section 402 (discharge of pollutants) and section 404 (discharge of dredged or fill material) b. Section 502(12) defines a discharge of a pollutant to include any addition of any pollutant to navigable waters from any point source or to the waters of the contiguous zone or the ocean from any point source other than a vessel or other floating craft. c. Defining Addition of Any Pollutant i. Tulloch Rule: excavation activities producing any incidental redeposit of dredged materials, however temporary or small. Challenged in National Mining Association v. Army Corps of Engineers National Mining Association v. Army Corps of Engineers (D.C. Cir. 1998) (p.671) Facts: Army Corps of Engineers promulgated the Tulloch Rule which said that if you do any dredging, they presume it will result in incidental redeposit. The Corps accepted the notion that this constituted a discharge, so a permit would be required. The trade association argued that incidental fallback is not a discharge so therefore it cannot be regulated. The Corps/EPA say that it is a pollutant because it can have a negative environmental impact. Holding: The Court rejects EPAs decision because there is no dredged material. Any incidental fallback is not a net addition. Borden Ranch Partnership v. Army Corps of Engineers Facts: Man used deep ripping equipment to punch holes in clay pan to drain wetlands constitutes adding a pollutant. Holding: Normal farming activities are exempt from 404. However, this was not normal farming activities/ he wasnt trying to drain for a legitimate farming purpose. ii. What is a point source 1. any discernable, confined and discrete conveyance (sucha as a pipe, ditch, channel or tunnel) from which pollutants are or may be discharged 2. the point source need not be the original source of the pollutant; it need only convey the pollutant to navigable waters (Miccosukee) NRDC v. Costle (D.C. Cir. 1977) (p.684) Facts: EPA wanted to exempt because it would be hard to come up with actual limits. They want to save their money and time for big sources that matter more. Holding: Finds for NRDC but says that EPA can do other things to lessen the burden, such as general permits.

U.S. v. Plaza Health Laboratories Question Presented: Is a person a point source? Holding: Legislative history makes clear that Congress wanted to go after big sources, not individuals like a kid throwing a candy wrapper into the ocean. Dupont v. Train (1977) Holding: EPA needs to start issuing permits even if they dont have numerical effluent limits established yet 3. Unitary Waters Test a. Traditional test: pollutant must be added or introduced to the navigable waters from the outside world. Mere transfer or movement of pre-existing pollutants form one water body to another not an addition of pollutants b. This is to be addressed on remand in Miccosukee Miccosukee Facts: Florida had a diversion program for flood protection. Pipes moved water. Holding: The pipes are a point source, even though they dont add pollutant themselves. Unitary Waters idea was not developed at lower level, so should be addressed on remand. III. Water Quality Standards a. Process for setting them: i. States and tribal authorities identify designated uses for each body of water within jurisdiction ii. After consulting EPAs water quality criteria, states and tribes promulgate water quality standards and submit them to EPA for approval. iii. States and tribes must review and revise their water quality standards every three years. b. WQ Standards and Designated Uses i. Supposed to meet fishable/swimmable goal unless that would result in substantial and widespread economic and social impact c. Problems with WQ Standards: i. Limitations of toxicity testing ii. Depends on where you sample the water to determine how toxic it is/ what toxins are present d. Total Maximum Daily Loads Pronsolino v. Nastri (9th Cir. 2002) Issue: Whether or not a body of water that fails to meet water quality standards entirely as a result of non-point source can be subject to TMDL Holding: It is up to the state to deal with the problem of when a water body fails to meet water quality solely as a result of non-source point pollution. EPA can say that water quality standards are being violated, but they cannot directly regulate the non-point sources. Read (1) pp. 670-678, 683-690, 698-701, 714-719, 739-748 in the casebook and (2) 402(a), 502(12) and 502(14) of Clean Water Act on pp. 880 and 896 in the Statutory and Case Supplement.

The Miccusukee Case Behind the Scenes during the Litigation.

Read pp. 678-683 of the casebook, the FOE v. SFWMD Cert Petition (you do not need to read the Appendices), the FOE v. SFWMD Response Brief, and the FOE v. SFWD Opposition Brief by the Solicitor General (all three of these briefs are posted in a folder that follows this section of the Courseware website). VII. LAND USE REGULATION Regulatory Takings Overview

Categories of per se takings o 1. If the government requires an owner to suffer a permanent physical invasion of her property it must provide just compensation (Loretto) o 2. A regulation that completely deprives an owner of all economically beneficial use of her property, except to the extent that background principles of nuisance and property law independently restrict the owners intended use of the property (Lucas) If it doesnt fit in one of these two categories, look to Penn Central test (weigh three factors when looking at all facts and circumstances) o Character of the government action o Degree to which it harms investment backed expectations o Extent of economic burden that it imposes on property Regulatory takings claims very rarely survive Land Use and the Environment, Federal and State Regulations and Introduction to Regulatory Takings. Read pp. 769-799 in the casebook. Village of Euclid v. Amber Realty Co. (1926) (p.784) Kelo v. City of New London (2005) (p.786) Pennsylvania Coal v. McMahon (1922) (p.794) Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York (1978) (p.795) Holding: When a regulation places limitations on land that fall short of eliminating all economically beneficial use, a taking nonetheless may have occurred, depending on a complex of factors including the regulations economic effect on the landowner, the extent to which the regulation interferes with reasonable investment backed expectations, and the character of the government action. Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp. (1982) (p.798) The Modern Revival of Regulatory Takings Jurisprudence. Read (1) pp. 799-824 in the casebook. Some regulations may so unreasonably limit the property owners rights that it should not be outcome determinative if they but it after the regulations (Palazzo) Courts now follow OConnors concurrence in Palazzo: when the owner bought the land in relation to the enactment of the regulation is evaluated as part of the investment-backed expectation factor in the Penn Central test o Scalia had argued that there isnt a problem with the developer getting a windfall, that is just smart business. This is not followed.

Keystone Bituminous Coal v. DeBenedictis (1987) (p.799) Facts: Identical to Pennslyvania Coal Holding: A law restricting the exercise of mineral rights was not a taking because it was designed to protect public health and safety by preventing subsidence of surface areas. Distinguished Pennsylvania Coal because there was no basis for finding htat the law made it impossible for the company to profitably engage in its business or that it had unduly interfered with investment backed expectations. First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. County of Los Angeles (1987) (p.799) Facts: California law made invalidation of the law the only remedy for a takings violation. Holding: While invalidation of an ordinance could make any taking a temporary one, the Constitution requires that the government pay the landowner for the value of the use of the land during this period. Nollan v. California Coastal Commission (1987) (p.799) Facts: Nollans wanted to build a small house on beachfront property that was in between two public beaches. Commission granted the permit conditioned on the Nollans granting the public an easement to pass along property. Holding: The permit condition was unconstitutional because it did not serve the same governmental purpose as the development ban, and therefore did not meet the nexus test between the condition and the justification for the ban. Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Community (1992) (p.801) Facts: Lucas bought beachfront lots but was not allowed to build on them because of risk of hurricane damage and beach erosion. Holding: Created a new categorical taking for when all economic value is lost. Note: This almost never applies because it is Palazzo v. Rhode Island (2001) (p.814) Facts: Palazzo came into possession of waterfront land after the state had designated it as coastal wetlands that could not be developed without a permit. Holding: Rejected the notion that post-regulation acquisition of property serves as an automatic bar to regulatory takings claims. Also rejected RISCs ruling that case was not ripe (because he could still appeal for permit) because it was clear from oral argument that Rhode Island was not going to give him a permit. Regulatory Exactions, Evolving Conceptions of Property Rights and Judicial Takings Regulators sometimes condition approvals of development projects on the developers agreement to do something to provide benefits to the public If you ask an owner to do something as a condition of a permit, there must be a nexus between the dedication and the construction that satisfies the rough proportionality test (Dolan) The rough proportionality test is satisfied by quantifying findings for individualized determination about the nature and extent of the environmental impact of the development. This finding should then be compared with what the city is asking the private owner to give up. (Dolan) Government action must substantially further state purpose (Agins). However, the test in Agins (substantially advances) is not a complete test. In Lingle, OConnor holds that a regulatory takings argument must also consider the burden on the landowner, therefore the

only options for evaluating a taking are Loretto, Lucas, Penn Central, or Nollan/Dolan nexus tests. Dolan v. City of Tigard (1994) (p.833) Facts: Store owner wanted to expand and pave parking lot. City conditioned permit on making the area near a creek (which flooded regularly) public and allowing a bike/ pedestrian path. Holding: There is a nexus, as the prevention of flooding and concern about traffic have a nexus to the requested action (unlike Nollan). However the nexus does not satisfy rough proportionality so the city loses. The runoff problem could be dealt with in less troublesome ways, and forcing the owner to give up a part of her property to the city is too essential a component of property ownership to be relatively necessary. Agins: Lindle v. Chevron (2005) (p.845) Holding: Overrules substantially advances test of Agins. Holds that the only ways to have a regulatory taking are through Loretto, Lucas, Penn Central, or Nollan/Dolan analyses. Stop the Beach Renourishment, Inc. v. Florida Dept. of Environmental Protection (1160 SCS) Facts: Florida put new sand on beach to prevent erosion and then claimed that the new stretch of beach was public property. FL law provided that the state could erect no structures and gave homeowners absolute right of access over strip. Owners sued, arguing that there was a judicial taking when the FL Supreme Court ruled that they hadnt lost anything. Holding: Court upholds Florida Supreme Court decision and splits 4-4 on whether there can be a judicial taking (Constitution does not say that it has to be Congress or Executive taking the land to make it a taking).

I.

VIII. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Read (1) pp. 857-869, 870-872, 887-897 in the casebook, (2) NEPA Legislative History Timeline and Principal Provisions of NEPA on pp. 971-972 of the Statutory and Case Supplement, (3) 102 of NEPA on pp. 974-975 in the Statutory and Case Supplement. Introduction to NEPA a. Structure of NEPA

Structure of NEPA 101: establishes as the continuing policy of the Federal Government the use of all practicable means to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony. 102(2)(C): requires all federal agencies to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) on major federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the environment. The EIS must include a detailed statement of environmental impacts, alternatives to the proposed action and any irretrievable commitments of resources involved. 102(2)(E): requires all federal agencies to study alternatives to actions involving unresolved resource conflicts 201: requires the President to submit to Congress an annual Environmental Quality Report 202: establishes a three-member Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in the Executive Office of the President

204: outlines the duties and functions of CEQ including annual reporting on the condition of the environment, information gathering, and review and appraisal of federal programs and activities. b. The regulatory target of NEPA is federal agencies, not private industry. The goal of NEPA is to make it the job of every federal agency to factor environmental considerations into their decision making process. c. Jurisdictional terms: i. major Federal actions ii. significantly affecting the quality of the human environment d. Other requirements/ reasons for strength: i. Requires EIS ii. Created CEQ iii. Gives incentive to make accurate predictions because a company will be on the hook for environmental damage beyond what they forecast e. Judicial Review of NEPA (as laid out in Calvert Cliffs) i. Courts cannot reverse a substantive decision on its merits, under 101, unless the actual balance of costs and benefits that was struck was arbitrary or clearly gave insufficient weight to environmental values ii. However, if the decision was reached procedurally without individualized consideration and balancing of environmental factors- conducted fully and in good faith- it is the responsibility of the courts to reverse. [NEPA allows for substantive discretion, but has strict standard of compliance for procedure] Calvert Cliffs Coordinating Committee v. U.S. Atomic Energy Agency (D.C. Cir. 1971) (p.860) Facts: AEC issued regulations that required permit applicants to prepare an environmental report to accompany their applications. However, the AEC took the position that it did not have to consider the report unless parties raised specific challenges to it during the licensing process. CCCC argued that AECs regulations violated NEPA because they did not require the agency independently to assess environmental impacts. Stryckers Bay Neighborhood Council, Inc. v. Karlen (1980) (p.864) Facts: HUD prepared EIS and acknowledged that they did not pursue some alternative locations for a low income housing facility because it would create an unacceptable delay. Holding: HUD did consider the environmental consequences of its decision, which is what NEPA requires. Therefore, their decision is sound. II. When Must An Environmental Impact Statement Be Prepared: EIS must be prepared for proposals for legislation and other major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment. a. Proposals for legislation and other major federal actions i. legislative EISs have rarely been performed 1. final action by the President (such as NAFTA treaty) is not judicially reviewable because he is not an agency ii. Major Federal Action