Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Portfolios 1

Hochgeladen von

Barby FernandezOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Portfolios 1

Hochgeladen von

Barby FernandezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Portfolios in the EFL classroom: disclosing an informed practice

Alexandra Nunes

This article provides an overview of the work carried out over the period of one year with a group of 10th grade students in a Portuguese high school. It argues that by using portfolios in EFL classrooms, the teacher cannot only diagnose the learners skills and competences, but also become aware of their preferences, styles, dispositions, and learning strategies, thus being able to adopt a more learner-centred practice. The article >rst introduces the rationale for the use of portfolios with this group of students. Then it reports on their feedback, categorizing their re?ections into four domains. Finally, it draws some preliminary conclusions that suggest how the students re?ections can help the teacher make informed decisions and choices in the classroom, and also contribute to a greater student involvement in the teaching-learning process, and to more autonomous learners of English.

The purposes and contents of portfolios

There is a wide body of theoretical research that recommends the use of portfolios in EFL classrooms (Hedge 2000; Rea 2001). A range of de>nitions of the portfolio has also developed, illustrating the growth and diversity of its use. For some teachers, the portfolio is part of an alternative assessment programme, and it can either include a record of students achievements or simply document their best work. For other teachers, the portfolio documents the students learning process, and still others use it as a means of promoting learner re?ection. When talking about the kinds of evidence one may >nd in a students portfolio, Crockett (1998) considers portfolio contents to fall into >ve categories: i) found samples, which refer to pieces done to ful>l class assignments; ii) processed samples, or the students analyses and selfassessment of a work previously graded by the teacher; iii) revisions or samples of student work that have been graded and then revised, edited, and rewritten; iv) re?ections, which are related to the processed samples but are applied to the portfolio as a whole, providing a chance for students to think about who they are, what their strengths and weaknesses are; v) and portfolio projects, which cover work designed for the sole purpose of inclusion in student portfolios, and that can arise from a review of portfolios that reveals a particular interest or challenge to overcome. Given that the emphasis of the de>nition of the portfolio can shift from product to process according to the context and design of its

ELT Journal Volume 58/4 October 2004 Oxford University Press

327

articles

welcome

development, the portfolio can include the contents mentioned above, as well as other items considered relevant for its speci>c purpose.

Context of the study and principles of portfolio development

There has been a shift in many educational programmes from an emphasis on content and results to an emphasis on process and on the capacity of the learner to self-direct his/her acquisition of knowledge. In this approach, the teacher no longer acts as the locus for all instruction, and more and more the learners are acknowledged as playing an active role in the diagnosis of their weaknesses and strengths, as well as in the selection of processes and strategies to monitor and self-assess their learning, thus sharing responsibility for the acquisition and development of their linguistic knowledge and skills (Cohen 1998; Macaro 2001). Portfolios in the EFL classroom can be a useful tool for the promotion of active participation of students. However, in order to fully respond to the challenges of the current pedagogical thinking, we believe that the development of portfolios must follow two underpinning principles. The >rst tenet is that it should be dialogic, and facilitate on-going interaction between teacher and students. If the portfolio is to be conceived as an instrument of dialogue, it cannot be written in one session and handed in at the end of the academic year. On the contrary, it has to be continually in the making and document work in progress. In other words, it has to be developed in action, and shared so that it can facilitate focused intervention, decision-making, or joint problem-solving in due time. Following this principle, and in S-Chaves (1997: 140) words the portfolio may be conceived as a long letter written to ones self and to others, and always returned. However, when it gets back to the student it is enriched by new perspectives, new information, new insights, advice and support. (Translation by this author.) The second tenet of portfolio development in the context of our study is that it should document the re?ective thought of the learner. In fact, more and more, learners re?ection on their cognition process is acknowledged as an essential component of education (McCombs 1987; Wolf and Reardon 1996). Taking account of these two principles, we decided to embark on a programme of portfolio development with our 10th grade students, in a Portuguese high school. The objectives of our study were to >nd out how the record of student re?ection in the portfolio could contribute to a more informed approach to the teaching-learning process, as well as to promote a deeper involvement of the students with their learning.

Principles in developing portfolios

Introducing portfolios to our students

When we introduced this project to our students, we stated the educational aims of the portfolio, and widening the scope of its contents beyond the >ve categories presented by Crockett (1998), we told the students that in their portfolios they could include whatever they believed to be important for their learning process. Therefore, besides including representative samples of student work such as essays, compositions, revisions, tests, worksheets, summaries, drafts of assignments, or completed individual and group work, the portfolios could also contain pictures, texts, magazine, and newspaper articles that had a special

Alexandra Nunes

328

articles

welcome

meaning for the students and, above all, re?ections on whatever they believed to be important for them as learners and individuals.

First results

A couple of weeks after the presentation of the portfolio project, the >rst samples began to appear, but they revealed that the students didnt immediately grasp the aims and modus operandi of re?ection since it was absent from these >rst samples. When reading the students material, we didnt immediately understand the reason why a particular piece was included in the portfolio, what the students thought of it, or about anything else. In spite of the fact that these students had been attending high school for four years, they were obviously not used to thinking about their learning, and were therefore at a loss with the re?ective task that they had been assigned. Research recognizes students re?ections and awareness of their work, performance, and cognitive processes as important factors in the way they use their learning strategies and monitor their future performance (Wolf and Reardon 1996). In this particular study the students wrote their re?ections in the target language, and not in their mother tongue, which might be considered an added burden on an already demanding task. This can also mean a more di;cult task for the teacher who has to interpret not only the students re?ections, but also the way these are represented through a language that is being learnt. However, in the long run, and if the students become familiar with the language of self-re?ection, which is an important step to the control of their metacognitive processes (Herbert 2001), producing re?ections in the target language can bring about important advantages for both students, who use the foreign language far beyond the classroom time and locus, and teachers, who re>ne their insight into many of the students language needs, thus being able to adopt a more informed practice.

Developing reflection

As a means of helping the students to re?ect on their learning, we used questionnaires in which they had to answer questions related to their learning process, such as what they have learnt in a particular class, what di;culties they have found, and why, among others. We also dedicated classroom time to the explicit training of learning strategies, having them describe, model, and give examples of the strategies they used to solve particular tasks, as well as by presenting, describing, and providing practice of new strategies so that they became aware of alternative ones. Eventually, these initiatives bore fruit, transforming the portfolios into a curriculum for thinking about learning, that is, a central curricular framework for the development of the students metacognitive awareness (Herbert 2001). So we can say that after a somewhat weak beginning in portfolio development, in which silence and chaos reigned, in the end, the students voices began to be heard.

Data analysis Dialogue

Although the majority of the portfolios produced by the students illustrated the idiosyncrasies of their authors, and were unique and single creations (S-Chaves 1998) (translation by this author), it is also possible to >nd some commonality as far as the focus of their re?ection is concerned, though its language and substance are di=erent.

Portfolios in the EFL classroom 329

articles

welcome

A content analysis of the portfolios displays the emergence of several recurring issues that the learners had re?ected on in their entries, as well as the two principles of portfolio development referred to previously. With regards to its dialogic nature, the students entries reveal an interaction that took place at di=erent levels, not only at an interpersonal level between teacher and student, but also at more intrapersonal and inter-textual levels, for example interaction between the student and himself/herself, between the student and his/her writings, between the student and other writings and so on. Examples of records that illustrate this dialogism appear below (the students are referred to by the initials of their names): Teacher, Finally I have cable TV at home. My father bought it in Christmas and now I can watch more programs in English, like >lms without legends, programs about nature, etc. I think this helps me to learn English better, dont you think so to? (PM, on 4th January) PM, I am glad you are able to watch TV programmes in English (with no captions, I hope), since being exposed to the language that you are learning beyond the classroom time can be rather bene>cial. In fact, the more you listen to and try to speak the English language, the more you are likely to improve your language skills (Teachers reply on 7th January) (Students reaction to some of her mistakes in the test) I sometimes am very angry with myself. For example, I know very well that we use the in>nitive (withoutto) after modal verbs, but I wrote it wrong in the test! I feel like scream to myself: Why dont you pay more attention?! (AP) The text that we read last lesson from our book (Is it hip to buy?) illustrates very well what is consumerism: buy, buy and buy again. In my opinion, the consumerism is caused by an excess of advertising. (. . . ) Advertising doesnt in?uentiats only adults but also children. As Jane Mathews says in Time magazine: Its an enormous market thats not been fully tapped ordare I use the wordexploited. I also think that advertisers are exploiting children and when they target children they want to get to the parents pockets. (AT) We consider all of these dimensions of dialogue to be important since they provide a) an opportunity for a more personal and comprehensive relationship between students and teacher, who can also take more informed actions and understand some educational episodes more easily; b) a chance for students to know themselves better, their strengths and weaknesses and, consequently, monitor their future actions and performances; c) as well as an opportunity for students to relate their opinions to those of others, thus helping them to assess several viewpoints, keep an open mind to diversity, and even construct, widen, and reconstruct their own knowledge.

330

Alexandra Nunes

articles

welcome

Reflection

The second principle of portfolio development that we mentioned in the >rst part of this article is re?ection, and for the current study, only entries that brought the dimensions and levels of the students re?ective thought to light were selected. In attempting to identify what the students most re?ected on, we grouped the entries according to the issues that repeatedly appeared, and this highlighted four areas: syllabus, instruction, learning, and assessment. Under syllabus, we grouped the re?ections on the contents included in the syllabus, in terms of their relevance for the students, and in terms of their emotional reactions to the theme, e.g. I like English and the themes discussed in class, specially the theme Space Exploration. I liked this theme very much because it is related to my area of study in school (Sciences), because the space is still something unknown out there, and because knowledge in this area is in constant change and evolution. (AT) In the area of instruction, we included the students re?ections on teaching aids and materials, teaching methods, instructional activities, strategies, and tasks. Two examples of the several entries considered in this category appear below: What I liked the more in this class were the pictures of some traits and characteristics of Mars that the teacher showed. I found the Happy Face on Mars very interesting, but I also liked the group work and to speculate with my colleagues about what those pictures could represent, before reading a text about them. (. . . ) I really think that changing ideas with our colleagues in English improves our competence and makes classes more interesting. (PM) In this class I liked the debate in groups about the advantages and disadvantages of tourism. It was interesting to hear the opinions of the di=erent groups. However, I think that the text about Ecotourism was a bit di;cult because I didnt know many words. (CS) Entries grouped under the heading learning include re?ections on the contents dealt with in class, on the students weaknesses, strengths, needs, and learning strategies. This category also includes re?ections on mistakes produced in written essays and compositions, or in exercises from grammar books, worksheets, and others. The re?ections below illustrate some of the issues referred to by the students: I think I improved my competence in English due to study a lot and to some learning strategies that I used. I always tried to speak in English in class and I read and wrote a lot of texts. When a text had some words that I didnt understand, I tried to infer their meaning from context or I asked my colleagues. At home I used the dictionary. (AT) (Extract from a composition about technological development and re?ection about the mistake made) . . . The telephone and the telegraph were two importants inventions . . . This is wrong because adjectives in English dont have a plural form. (G T )

Portfolios in the EFL classroom 331

articles

welcome

One of the things I do a lot now and that I didnt do in 9th class is to summarise many texts we read in class. I think this helped improve my writing capacity because I write a lot and get habituated to the structure of the sentences. Writing helps me to learn and many of the exercises that we do in class (like to write topic sentences to summarise the main ideas of the paragraphs of texts) helped me make many resumes. (PM) Under assessment, we grouped re?ections on the students competence and skills, their performance in classroom tasks and in conventional tests, as well as re?ections on the portfolio itself. Examples of some of these entries appear below: I think my portfolio is complete. It has many texts, many re?ections about grammar, themes and also many exercises. What I like most in my portfolio are the texts I write about the themes of the classes. When I write about a subject I can understand this subject better and I have an opportunity to express my opinion. (AT) Group D of the test: This group (the student is referring to exercises in which he had to explain the meaning of expressions) is a new group, and it comes to substitute the group of synonyms. I say it is much more di;cult. I dont know if it is because I am not habituated. I dont understand if I have to do a new sentence and substitute some words for words that come in the dictionary or explain them. (AP) I think that I reached more or less my aims for the English subject because I learnt out to read English in a better way, I can understand better the >lms that are in English and I developed some communicative competence. I think I improved my competence in English due to some learning strategies that I used, like speaking English to my friends and to the teacher in class, consulting the dictionary at home, solving exercises from grammatical books and reading texts in English. (AM) Figure 1 shows the number of entries each area had in the portfolios of the fourteen students that participated in this study. Though there were sixteen students in the class, only fourteen participated in the portfolio study in a systematic way.

332

Alexandra Nunes

articles

welcome

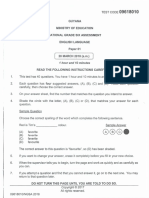

Domains of students re?ections Students (initials) AT CS RS GT HC PM MC AM AP AC LF ES JM

figure 1 Areas of students re?ections

Syllabus 6 3 2 3 2 2 6 5 7 1 1 5 2 3 480

Instruction 29 18 13 19 22 15 18 25 26 11 10 22 11 14 2530

Learning 33 25 12 22 25 17 22 29 32 14 12 25 12 17 2970

Assessment 11 7 6 7 8 7 6 8 10 6 4 8 5 6 99

CT Total

As Figure 1 makes clear, most re?ective thoughts produced by the students in their portfolios focused on the domains of instruction (36%) and learning (43%), whereas only 14% of all entries focused on assessment and 7% on the syllabus. This may suggest that many students didnt consider assessment as part of the ordinary classes, but as an isolated moment associated with conventional tests (which occurred approximately twice every three months). This misconception is probably the result of a long tradition in education that focuses on results and products, and may also explain the fact that only eight out of fourteen students produced re?ections on assessment that were not directly related to tests. It is also somewhat surprising that, with the exception of >ve students (AT, MC, AM, AP, and ES) who re?ected on the syllabus when they considered it interesting, relevant or not so interesting, the rest of the class only produced re?ections on the syllabus when they really didnt like the theme discussed in class. In this respect, the few classes that dealt with history (namely with the Victorian Era) produced the highest number of entries in the students portfolios. The students re?ections revealed di=erent levels of complexity, from a more elementary level of thought to a higher level of metacognition. Nevertheless, we believe that all re?ections are valuable since they may serve di=erent functions. If we consider the re?ections the students produced on the syllabus and on instruction, we have to conclude that they provide invaluable information to the teacher, who has access to a deeper knowledge of the contents, activities, materials, and strategies the students prefer. In this way, the teacher can design future instructional strategies, materials and activities that are more meaningful and valuable

Portfolios in the EFL classroom 333

The value of reflection

articles

welcome

to the learners, as well as make curricular decisions and choices, which will enhance their motivation and involvement in class. The re?ections that focused on the students learning provide the teacher with a better understanding of their preferred learning styles, needs, and di;culties. This information also allows the teacher to adjust instruction to the students individual goals, needs, and learning dispositions. However, and above all, we consider that the students re?ections about learning can help them to become autonomous learners. In fact, by analysing the e;cacy of the strategies used to accomplish certain tasks, the students can make curricular decisions, such as to continue using them, or in case they prove ine=ective, discontinue their use. As far as the re?ections on assessment are concerned, we >rmly believe these can play an important role not only in activating the students metacognitive strategies but also in promoting their autonomy. Self-assessment may be de>ned as the ability to make judgements about what one knows and does. When the students accurately identify weaknesses in their learning they can more promptly and accurately self-monitor their learning process and consider what action to take to overcome those shortcomings. Re?ective dialogue can promote metacognition, that is, thinking about ones thinking and learning. Hacker (cited in Klenowski 2002: 33) considers that the de>nitions of metacognition need also to include knowledge of ones knowledge, processes and cognitive and a=ective states as well as the ability to consciously monitor and regulate ones knowledge, processes and cognitive and a=ective states. As learners become more aware of the state of their knowledge and of their strategies for learning, they can more easily identify obstacles to their learning and, by exercising control over their learning strategies, they can begin considering solutions for those problems.

Conclusion

Though our study was an exploratory one that dealt with a particular learning context, we believe that it has clear implications for teachers working in a variety of situations and it would be interesting to see if further studies point in the same direction. This article presented a case for making re?ection through the portfolio experience an integral part of EFL learning. As Herbert (2001: 55) says, in the portrayals of successful learning environments, it is considered essential to give children means by which they can express and expand their understanding of their own learning processes. The portfolio, considered as an instrument that can foster students re?ection, can also help them self-monitor their own learning, thus helping them to become more autonomous learners. In the light of current pedagogical thinking, and as our study revealed, the portfolio can also be a useful pedagogical tool in that it facilitates the adoption of a more learner-centred practice as well as the integration of assessment, teaching and learning with the curriculum. Revised version received July 2003

334

Alexandra Nunes

articles

welcome

References Cohen, A. D. 1998. Strategies in Learning and Using a Second Language. London: Longman. Crockett, T. 1998. The Portfolio Journey: A Creative Guide to Keeping Student-Managed Portfolios in the Classroom. Eglewood: Teacher Ideas Press. Hedge, T. 2000. Teaching and Learning in the Language Classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Herbert, E. 2001. The Power of Portfolios: What Children Can Teach us about Learning and Assessment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Klenowski, V. 2002. Developing Portfolios for Learning and Assessment: Processes and Principles. London: Routledge. Macaro, E. 2001. Learning Strategies in Foreign and Second Language Classrooms. London: Continuum. McCombs, B. 1987. Issues in the measurement of standardized tests of primary motivational variables related to self-regulated learning. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Washington, D.C. Rea, S. 2001. Portfolios and process writing: a practical approach. The Internet TESL Journal Vol. VII (6). http://iteslj.org/Techniques/ReaPortfolios.html S-Chaves, I. 1997. Novas abordagens metodolgicas: os portfolios no processo de desenvolvimento pro>ssional e pessoal dos

professores in VII Colquio da Association Francophone Internationale de Recherche en Sciences de lducationMtodos e Tcnicas de Investigao Cient>ca. Lisboa. S-Chaves, I. 1998. Porta-flios: No ?uir das concepes, das metodologias e dos Instrumentos in L. S. Almeida and J. Tavares (org.). Conhecer, Aprender, Avaliar. Porto: Porto Editora. Wolf, D. and S. Reardon. 1996. Access to Excellence through New Forms of Student Assessment in J. Baron and D. Wolf (eds.). Performance-based Student Assessment: Challenges and Possibilities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. The author Alexandra Castro Nunes holds a Masters degree in Anglo-American Studies from the University of Porto and at the moment is conducting research for her Doctoral dissertation in Education, in the University of Aveiro. She has served as an English language teacher both in secondary schools and colleges, and has also been a mentor of beginning teachers and a supervisor of sta= development programs. She has published coursebooks for secondary school students, as well as several articles on educational topics, including methodology and didactics, supervision and sta= development. Email: alexandra_nunes@iol.pt

Portfolios in the EFL classroom

335

articles

welcome

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- KableDokument24 SeitenKableDiego Felipe FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Countable Nouns and Uncountable Nouns 1Dokument2 SeitenCountable Nouns and Uncountable Nouns 1florNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENW311 Journals and DiariesDokument28 SeitenENW311 Journals and DiariesBella Amelia Resmanto100% (1)

- Тест по ОТЯDokument8 SeitenТест по ОТЯaishagilmanova771Noch keine Bewertungen

- Past Simple vs ContinuousDokument2 SeitenPast Simple vs ContinuousIrina TsudikovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation Sheet: Oral Presentation ECE 3005: Professional and Technical CommunicationDokument1 SeiteEvaluation Sheet: Oral Presentation ECE 3005: Professional and Technical CommunicationNik ChoNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Grade 6 Assessment 2018 English Language Paper 1Dokument20 SeitenNational Grade 6 Assessment 2018 English Language Paper 1Grade6Noch keine Bewertungen

- Passive Voice TutorialDokument37 SeitenPassive Voice TutorialmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carakumpul - Blogspot.com - Soal PTS Genap 7 Bahasa InggrisDokument3 SeitenCarakumpul - Blogspot.com - Soal PTS Genap 7 Bahasa Inggrisatika putri karinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- VERBSDokument1 SeiteVERBSEs Jey NanolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unidad Académica Profesional Cuautitlán IzcalliDokument4 SeitenUnidad Académica Profesional Cuautitlán IzcalliLuis Israel ValdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparison Between The Effectiveness of Mnemonic Versus Non-Mnemonic Strategies in Foreign Language Learning Context by Fatemeh Ahmadniay Motlagh & Naser RashidiDokument8 SeitenA Comparison Between The Effectiveness of Mnemonic Versus Non-Mnemonic Strategies in Foreign Language Learning Context by Fatemeh Ahmadniay Motlagh & Naser RashidiInternational Journal of Language and Applied LinguisticsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handbook of VolapukDokument136 SeitenHandbook of VolapukAJ AjsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loonie Criteria Score: Name Level Beginner ResultDokument2 SeitenLoonie Criteria Score: Name Level Beginner Resulterinea081001Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tato Laviera - AnthologyDokument5 SeitenTato Laviera - AnthologyElidio La Torre LagaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Distributions - Group 2 PhonologyDokument19 SeitenDistributions - Group 2 PhonologyWindy Astuti Ika SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENG 203-Course OutlineDokument19 SeitenENG 203-Course OutlineMd. Kawser AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mastering HazelcastDokument232 SeitenMastering Hazelcastacsabo_14521769100% (1)

- Advanced Reading Writing QP Finial 2019Dokument2 SeitenAdvanced Reading Writing QP Finial 2019SHANTHI SHANKARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pokorny in Do European DictionaryDokument3.441 SeitenPokorny in Do European DictionaryKárpáti András100% (4)

- Scholarship Legal UNTranslationDokument2 SeitenScholarship Legal UNTranslationSamiha AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kawarazaki Mikio Ri Ben Yu Kanaru Men Nihongo Kana An IntrodDokument103 SeitenKawarazaki Mikio Ri Ben Yu Kanaru Men Nihongo Kana An IntrodОля Ощипок100% (1)

- Poetry Long Form - Green Eggs and HamDokument7 SeitenPoetry Long Form - Green Eggs and Hamapi-450536386Noch keine Bewertungen

- TFL Editorial Style GuideDokument48 SeitenTFL Editorial Style GuideFeliks CheangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vdoc - Pub Handbook of Communications DisordersDokument971 SeitenVdoc - Pub Handbook of Communications DisordersDavid OliveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSS Pashto MCQs - Pashto Important Mcqs For CSS PMS KPPSCDokument4 SeitenCSS Pashto MCQs - Pashto Important Mcqs For CSS PMS KPPSCijaz anwar100% (1)

- ThousandsDokument2 SeitenThousandsOm AutadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vocab in ContextDokument21 SeitenVocab in ContextbaltosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017年全国高考英语试题及答案 全国卷2Dokument10 Seiten2017年全国高考英语试题及答案 全国卷2The Mystic WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Newton C++ Tools Programmer's ReferenceDokument182 SeitenNewton C++ Tools Programmer's Referencepablo_marxNoch keine Bewertungen