Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kaczinska Elwira - Hesychius On Lykophron

Hochgeladen von

strajder7Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Kaczinska Elwira - Hesychius On Lykophron

Hochgeladen von

strajder7Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HESYCHIUS ON LUKFRWN

ELWIRA KACZYSKA

d According to Hesychian definition, the meaning of the adjective lukfrwn, explained commonly as wolf-minded, is high-minded, adding not irrelevant evidence for the adjectival root *luk -, high.

In his glossary Hesychius, the well known lexicographer from Alexandria, explains the adjective lukfrwn by means of two equivalents deinfrwn and yfrwn 1. The former word deinfrwn appears only once in the ancient texts and therefore it must be classified as hapax legomenon. However, we cannot treat this word as a corrupted form, as both components of the compound, deinj and frn, are easily identified. It denotes nothing other than clever-minded. The latter word can be easily corrected into yfrwn (an itacism) or perhaps yhlfrwn. Both these adjectives mean high-minded, high-spirited, haughty. It is obvious that the same semantics (high-minded, clever-minded or the like) should be suggested for lukfrwn. The traditional explanation of this adjective is based on the association of the first element luk- with Greek lkoj wolf. Thus the word in question is commonly explained as wolf-minded 2.

1

Hesychii Alexandrini Lexicon, recensuit et emendavit K. Latte, vol. 2, Hauniae !966 (henceforth: HAL), p. 613, l-1401: lukfrwn : deinfrwn, yfrwn. 2 Cf. A Greek-English Lexicon, compiled by H. G. Liddell and R. Scott, revised and augmented throughout by H. S. Jones, Oxford 1996, p. 1065. EMERITA. Revista de Lingstica y Filologa Clsica (EM) LXIX 2, 2001 pp. 263-267

264

ELWIRA KACZYSKA

EM LXIX 2, 2001

This etymology is probably wrong, as a number of ancient sources demonstrates the existence of the archaic adjectival root luk- meaning high in Ancient Greek. This root is attested not only in the dialectal vocabulary, but also in many oronyms and toponyms. Now I would like to discuss both lexical and onomastic data.

Lexical evidence. Stephen of Byzantion, the Greek lexicographer of the sixth century AD, gives a double etymology of the place-name Lktoj 3:

Lktoj, plij Krthj, p Lktou to Lukonoj. nioi Ltton atn fasn di t kesqai n meterw7 tpw7. t gr nw ka yhln ltton fas. t qnikn Lktioj, ka qhlukn Lukthj.

The first explanation, deriving the name from the mythical eponym Lyktos, Lykaons son, belongs to the so-called folk etymologies. The second derivation connects the place name Lktoj with the positive topographical feature: the city is situated in a highland place (t kesqai n meterw7 tpw7) and the appellative lyttos means high, lofty, high-raised (t gr nw ka yhln ltton fas). The same appellative is quoted by Hesychius (l-1470): lttoi : o yhlo tpoi 4. However, Pierre Chantraine does not exclude that the Hesychian gloss may be an invention to explain the origin of the Cretan place-name Lyktos 5. The dialectal word lttoj derives from hypothetical *lktoj, similarly as the place-name Lttoj develops from Homeric Lktoj 6 and Mycenaean

Stefanos of Byzantium EQNIKWN. A Geographical Lexicon on Ancient Cities, Peoples, Tribes and Toponyms, Chicago, 1992 (a reprint of the German edition: Stefani Byzantinii Ethnicorum quae supersunt, ex recensione Augusti Meinekii, Berlin, 1849), p. 422, sub. v. Lktoj. 4 HAL II, p. 615 (henceforth: HAL). See also R. A. Brown, Evidence for Pre-Greek Speech on Crete from Greek Alphabetic Sources, Amsterdam, 1985, p. 78; A. Th. Vasilakis, Ti kretiko lexikologio, Iraklio, 1998, pp. 112-113. 5 P. Chantraine, Dictionnaire tymologique de la langue grecque. Histoire des mots, Paris, 1984, p. 652, sub. v. lttoj. 6 Lyktos (or later Lyttos) was one of the oldest and most powerful Cretan city-states of Classical Greek times and a bitter enemy of Knossos. It was quoted by Homer in his wellknown catalogue of ships among seven central towns of Crete (Il. II 645-649).

3

EM LXIX 2, 2001

HESYCHIUS ON LUKFRWN

265

ru-ki-to 7. Strabo remarks that the Homeric form Lktoj differs from the actual Cretan name Lttoj. August Fick observes that the afore mentioned process, analogical to 9Attikj < 9Aktikj, is due to the regressive assimilation of consonants 8. M. Schmidt explains this process as purely Cretan, referring to the Hesychian gloss dittaj : rgodikthj. Inscriptions, found in the central part of Crete, register many other instances of the regressive assimilation -tt- < -kt- 9. It is clear now that the adjectival form lttoj, meaning high, lofty, highraised, derives evidently from the suggested root *luk-. What is more, it must be the old superlative luk-istos. In my paper on the Mycenaean name of Lyktos I tried to prove that the Mycenaean spelling ru-ki-to, ethnic ru-ki-tijo, contains the suffix -isto- (like Faistj, Kdiston) and represents nothing other than Lukistos 10. The Homeric form Lktoj might be a straightforward continuant of the Mycenaean place-name, if we would accept an early (but post-Mycenaean) syncope of -i- 11. A similar process appears in a Cypriote dialect, in which the Apollons epitheton Mgistoj was changed to Mktoj (dat. sg. me-ko-to) 12. It is clear that *Mgstoj, the syncopated form

7 The form ru-ki-to is attested in many Knossian tablets, e.g. KN Da 1288, Dm 1177, Fh 349, and so on, cf. J. Chadwick, L. Baumbach, The Mycenaean Greek Vocabulary, Glotta 41, 1963, p. 219; A. Morpurgo, Mycenaeae Graecitatis Lexicon, Roma, 1963, p. 300; F. Aura Jorro, Diccionario Micnico, vol. 2, Madrid, 1993, p. 268. 8 A. Fick, Vorgriechische Ortsnamen als Quelle fr die Vorgeschichte Griechenlands, Gttingen, 1905, p. 13. 9 Cf. J. Brause, Lautlehre der kretischen Dialekte, Halle, 1909, p. 162-163; Brown (n. 4 above), p. 161. C. D. Buck, The Greek Dialects. Grammar, Selected Inscriptions, Glossary, Chicago, 1955, p. 73, adds: Assimilitation is most extensive in Crete. 10 E. Kaczyska, Remarks on the Mycenaean name of Lyktos, DO-SO-MO 3, 2001 (in press). The reading ru-ki-to = Lukistos was suggested e.g. by C. J. Ruijgh, tudes sur la grammaire et le vocabulaire du grec mycnien, Amsterdam, 1967, p. 180, fn. 413, and R. D. Woodard, Kadmos 25, 1986, p. 63. Also J. L. Melena, Minos 15, 1976, p. 148, preferred a primitive form *Lykistos, hence Lykastos by influence of Gk. stu city. There is no need to postulate the latter process in the case of Lyktos. 11 M. D. Petruevski, Zur Toponomastik Griechenlands im mykenischen Zeitalter, in: Neue Baitrge zur Geschichte der Alten Welt, vol. 1: alter Orient und Griechenland, Berlin, 1964, p. 166. 12 G. Neumann, Kyprisch qej Mktoj 9Apllwn, Zeitschrift fr vergleichende Sprachforschung 87, 1973, pp. 158-160; M. Egetmeyer, Wrterbuch zu den Inschriften im kyprischen Syllabar, Berlin-New York, 1992, p. 89.

266

ELWIRA KACZYSKA

EM LXIX 2, 2001

of Mgistoj, yielded regularly Cypr. Mktoj, as the Greek sequence of -gst(or -kst-) simplifies into -kt-, cf. Gk. ktoj sixth < IE. *swekstos (see Latin sextus, Germ. *swehstaz). By analogy the Mycenaean toponym ru-ki-to (= Lkistoj) developed to *Lkstoj by the syncope of -i-, further to (Homeric) Lktoj and consequently to Cretan Lttoj by assimilation of consonants. The Mycenaean spelling suggests strongly that the ancient name of Lyttos was Lukistos. This form is, of course, a superlative derived from the newly identified adjective *luk- denoting high. This stem was preserved only in the dialect of Crete: in fact, lttoj (originally *lkistoj) was an adjective in the superlative grade and it meant yhltatoj rather than yhlj. However, the Mycenaean evidence appears a perfect proof that the Hesychian gloss lttoi : o yhlo tpoi, as well as the testimony by Stephen of Byzantion, registered an actual Cretan idiom. It is certain now that the word lttoj was not an invention of Greek lexicographers to explain the origin of the Cretan place-name Lyktos.

Onomastic evidence. It is apparently certain that the place-name Lyktos must be etymologically connected not only with the Hesychian gloss (lttoi : o yhlo tpoi), confirmed independantly by Stephen of Byzantion (t gr nw ka yhln ltton fas), but also with a number of Pre-Greek oronyms, which contain the same element *luk- high (different than lkoj wolf):

1) Lukabhttj mountain in Attica, now in Athens. 2) Lkaion mountain in Arcadia apparently not connected with lkoj 13, originally high mountain. 3) Luknh mountain in Arcadia. 4) Lukwrej a summit of Parnassos in Phocis.

It is highly probable that the same explanation should be suggested to explain some Greek toponyms, situated in the mountains, e.g.

A. Bieleckij, The Oronymy of Greece, in: Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Congress of Onomastic Sciences, Cracow, August 21-25, 1978, ed. K. Rymut, vol. 1, Wrocaw-Warszawa-Krakw-Gdask-d, 1981, p. 190.

13

EM LXIX 2, 2001

HESYCHIUS ON LUKFRWN

267

5) Lukreia or Lukwrea a town near Delphi in the Parnassos massive; note a semantical equivalent 'Akrreia a summit in Sicyon and a town in Elis. Both names denote mountain heights. 6) Lukoura a town in North-Eastern Arcadia. This toponym is named after high mountains (luk- high and roj mountain) rather than derived from the compound of lkoj wolf and or tail (literally wolftail). 7) Lkastoj a town in Crete. It denotes most probably an upper or higher city (see luk- high and stu town, city) by analogy to krpolij (upper or higher city, hence citadel, castle). Similar formations are well known in the Greek toponymy (e.g. Acro-polis in Athens), as well as in the the onomastics of other Indo-European languages (e.g. Acro-briga town in Lusitania, Wye-hrad castle in Praha).

The root luk-, seen in the Greek oronymy and toponymy, seems to be connected with the highly situated places. Thus the onomastic data strongly confirm the lexical evidence.

Conclusions. The Ancient Greek evidence for the adjectival root *luk- high seems firmly established. The Hesychian gloss lukfrwn : deinfrwn, yfrwn may be added to the testimony. The equation lukfrwn = yfrwn (or yhlfrwn) suggests that the component luk- may be treated as the exact semantical equivalent of the Greek form yi adv. on high, aloft (as well as yhlj adj. high, lofty, high-raised).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Down and Out On The Quays of Izmir-M FuhrmannDokument32 SeitenDown and Out On The Quays of Izmir-M Fuhrmannstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Time and Timekeeping in The Balkans. Re PDFDokument37 SeitenTime and Timekeeping in The Balkans. Re PDFstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Muchan Jewish Quarter GuideDokument10 SeitenMuchan Jewish Quarter Guidestrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- WP011 PDFDokument18 SeitenWP011 PDFstrajder7100% (1)

- Census System and Population, 1831-1914 (1978)Dokument15 SeitenCensus System and Population, 1831-1914 (1978)warrior_quickNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Kurz3 PDFDokument30 Seiten4 Kurz3 PDFstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ška Proučavanja, (Akademija Umetnosti, Univerzitet U Novom Sadu), Metric Feet - A Comparative Ethnomusicological Study)Dokument3 SeitenŠka Proučavanja, (Akademija Umetnosti, Univerzitet U Novom Sadu), Metric Feet - A Comparative Ethnomusicological Study)strajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Ottoman Conquest and The DepopulatioDokument24 SeitenThe Ottoman Conquest and The Depopulatiostrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Muchan Jewish Quarter GuideDokument10 SeitenMuchan Jewish Quarter Guidestrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- CzechDokument6 SeitenCzechstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- WP011 PDFDokument18 SeitenWP011 PDFstrajder7100% (1)

- Kniha File 334 History of The Jews in HungaryDokument3 SeitenKniha File 334 History of The Jews in Hungarystrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Workbook 1 The Ottoman Empire-Chapter 1Dokument12 SeitenWorkbook 1 The Ottoman Empire-Chapter 1strajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- A History of The Jews in PragueDokument16 SeitenA History of The Jews in Praguestrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cidoc CRM Version 6.2.1Dokument250 SeitenCidoc CRM Version 6.2.1strajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Macedonian ProblemDokument137 SeitenThe Macedonian Problemstrajder7100% (1)

- About The Fiscal Status of The Greek OrtDokument14 SeitenAbout The Fiscal Status of The Greek Ortstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- CzechDokument6 SeitenCzechstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Muchan Jewish Quarter GuideDokument10 SeitenMuchan Jewish Quarter Guidestrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- 18 The Language of Non, Athenians in Old Come, DyDokument14 Seiten18 The Language of Non, Athenians in Old Come, Dystrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- DownloadedDokument18 SeitenDownloadedstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Bulgarians I in AmericaDokument13 SeitenThe Bulgarians I in Americastrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- 10 RobertDokument8 Seiten10 Robertstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Les Ottomans Et Le Temps PDFDokument400 SeitenLes Ottomans Et Le Temps PDFle-perfectionniste100% (4)

- Novasrbija 00 DediDokument363 SeitenNovasrbija 00 Dedistrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- The River in The Mythical and Religious Traditions of The Paeonians - Nikos ČausidisDokument23 SeitenThe River in The Mythical and Religious Traditions of The Paeonians - Nikos ČausidisSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Pre-Roman and Roman DardaniaDokument17 SeitenPre-Roman and Roman DardaniaAnitaVasilkova100% (1)

- Ekrem Hakki Ayverdi 30 Yil Hatira Kitabi-LibreDokument2 SeitenEkrem Hakki Ayverdi 30 Yil Hatira Kitabi-Librestrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Vernacular Romanization Vernacular Romanization Upper Case Letters Lower Case LettersDokument2 SeitenVernacular Romanization Vernacular Romanization Upper Case Letters Lower Case Lettersstrajder7Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Lexical Features of Microtoponyms of ZhondorDokument5 SeitenLexical Features of Microtoponyms of ZhondorOpen Access JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Lochs in Scotland MainlandDokument21 SeitenList of Lochs in Scotland MainlandAnnon1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Geographical Names On 16th and 17th Century Maps of Croatia: Josip FarièiæDokument32 SeitenGeographical Names On 16th and 17th Century Maps of Croatia: Josip FarièiæDrogo MejezelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prezime Ime Ime Oca JMBG AdresaDokument14 SeitenPrezime Ime Ime Oca JMBG AdresaSesti NalogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Onomastics - WikipediaDokument4 SeitenOnomastics - Wikipediamae mahiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ajdar KristinaDokument5 SeitenAjdar KristinaALEKSANDAR JEJINICNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Algeo, John Algeo, Katie) Onomastics As An Interdisciplinary StudyDokument10 Seiten(Algeo, John Algeo, Katie) Onomastics As An Interdisciplinary StudyMaxwell MirandaNoch keine Bewertungen

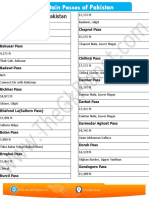

- Mountain Passes of PakistanDokument3 SeitenMountain Passes of PakistanMohsin Raza Maitla0% (2)

- Zgusta, The Terminology of Name StudiesDokument15 SeitenZgusta, The Terminology of Name StudiesDan PolakovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Semantic Classification of Hydronyms in Banat: Virginia DAVIDDokument13 SeitenThe Semantic Classification of Hydronyms in Banat: Virginia DAVIDGeorge IonașcuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chitral-From Toponymy To DemonymyDokument3 SeitenChitral-From Toponymy To Demonymyahnaaf0% (1)

- Orpheus: Journal of Indo-European and Thracian StudiesDokument46 SeitenOrpheus: Journal of Indo-European and Thracian StudiesCristian AiojoaeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spe (BPNT)Dokument102 SeitenSpe (BPNT)Fitrawati Amd Keb SkmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gazeteer of Chinese Geographical Names PDFDokument650 SeitenGazeteer of Chinese Geographical Names PDFbobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name and NamingDokument6 SeitenName and NamingRoberto AlarcónNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deo 2Dokument18 SeitenDeo 2Svetlana GrmušaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greenwald Jessica E-Power in Place-Names A Study of Present Day Waterford County, IrelandDokument85 SeitenGreenwald Jessica E-Power in Place-Names A Study of Present Day Waterford County, IrelandqpramukantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Eponyms, ToponymsDokument37 Seiten12 Eponyms, ToponymsEsatEccoGicićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hungarian Village FinderDokument7 SeitenHungarian Village FinderLuncan Gal HajnalkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Placenames: Es 8 ElDokument448 SeitenPlacenames: Es 8 ElBeso KobakhiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploring Microtoponyms Through Linguistic and Geographic PerspectivesDokument4 SeitenExploring Microtoponyms Through Linguistic and Geographic PerspectivesPhi Yen NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contents - VIIDokument4 SeitenContents - VIIJuan ArrevaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Place Names As Intangible Cultural HeritageDokument1 SeitePlace Names As Intangible Cultural Heritageapi-277557146Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Place Names of Skiathos PDFDokument11 SeitenLiterary Place Names of Skiathos PDFRapha JoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Space Place Story Prospectus Ryan Azaryahu Foote FinalDokument15 SeitenSpace Place Story Prospectus Ryan Azaryahu Foote FinalNoor TayehNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Gazetteer of Peruvian Entomological Stations (Based On Lepidoptera)Dokument9 SeitenA Gazetteer of Peruvian Entomological Stations (Based On Lepidoptera)Luis Daniel PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osmanlı Trakya FethiDokument126 SeitenOsmanlı Trakya Fethihyd arnes100% (2)

- Directions in Urban Place Name ResearchDokument52 SeitenDirections in Urban Place Name ResearchKelly GilbertNoch keine Bewertungen