Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Niccacci-BH Verbal System

Hochgeladen von

claudia_graziano_3100%(2)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (2 Abstimmungen)

350 Ansichten21 SeitenThe document discusses the verbal system in Biblical Hebrew poetry. It argues that verbal forms in poetry play precise functions, similar to their functions in prose.

Specifically, it addresses two issues: 1) the phenomenon of alternating qatal and yiqtol forms referring to the same event, and 2) the function of yiqtol when it occurs in the first position of a sentence. Regarding the first issue, the author believes verbal forms should be analyzed based on their distinct functions, rather than comparative considerations. For the second issue, the author argues that sentence-initial yiqtol is volitive (like a jussive), even when not morphologically marked as such.

The author aims to illustrate how

Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe document discusses the verbal system in Biblical Hebrew poetry. It argues that verbal forms in poetry play precise functions, similar to their functions in prose.

Specifically, it addresses two issues: 1) the phenomenon of alternating qatal and yiqtol forms referring to the same event, and 2) the function of yiqtol when it occurs in the first position of a sentence. Regarding the first issue, the author believes verbal forms should be analyzed based on their distinct functions, rather than comparative considerations. For the second issue, the author argues that sentence-initial yiqtol is volitive (like a jussive), even when not morphologically marked as such.

The author aims to illustrate how

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

100%(2)100% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (2 Abstimmungen)

350 Ansichten21 SeitenNiccacci-BH Verbal System

Hochgeladen von

claudia_graziano_3The document discusses the verbal system in Biblical Hebrew poetry. It argues that verbal forms in poetry play precise functions, similar to their functions in prose.

Specifically, it addresses two issues: 1) the phenomenon of alternating qatal and yiqtol forms referring to the same event, and 2) the function of yiqtol when it occurs in the first position of a sentence. Regarding the first issue, the author believes verbal forms should be analyzed based on their distinct functions, rather than comparative considerations. For the second issue, the author argues that sentence-initial yiqtol is volitive (like a jussive), even when not morphologically marked as such.

The author aims to illustrate how

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 21

BIBLICAL HEBREW VERBAL SYSTEM IN POETRY

1. A Verbal Theory for Prose and Poetry

When I wrote the final chapter of my Syntax of the Verb as well as my paper Analysing

Biblical Hebrew Poetry,

1

I thought that verbal forms in BH poetry did not play precise func-

tions, or rather that their functions were not the same as in prose. In addition, it was and still is

fairly common opinion among scholars, although not always openly declared, that the verbal

forms in poetry, more than in prose, can be taken to mean everything the interpreter thinks ap-

propriate according to his understanding and the context. In recent years I changed my mind. I

think now, first, that different verbal forms need play different functions in BH poetry as is the

case in prose and, second, that the functions of the verbal forms in poetry are basically the same

as in prose, more precisely in direct speech.

2

For convenience, here is a summary table of the functions of the verbal forms of direct

speech in prose.

TEMPORAL

AXIS

MAIN LEVEL OF COMMUNICATION

(FOREGROUND)

SECONDARY LEVEL OF COMMUN.

(BACKGROUND)

Past (X-) qatal continuation wayyiqtol

(coordinated, main level)

cf. Deut 1:6 ff.; 5:2 ff.

x-qatal, non-verbal sentence,

x-yiqtol, w

e

qatal

(background)

Present Non-verbal sentence with /

without participle

cf. Gen 42:10-11

Non-verbal sentence with /

without participle

Future Indica-

tive

Non-verbal sentence

(esp. with participle)

continuation w

e

qatal

cf. Exod 7:17-18; 7:27-29

or:

Initial x-yiqtol continuation

w

e

qatal (in a chain)

x-yiqtol (background)

Future volitive Imperative w

e

yiqtol

(foreground)

cf. Num 6:24-26

or:

(x-) yiqtol cohortative/jussive

w

e

yiqtol (= foreground)

x-imperative

(background)

x-yiqtol (background)

Note:

Imperative w

e

yiqtol = purpose (in order to)

Imperative w

e

qatal = consequence (thus, therefore)

cf. Exod 25:2 8

2

The main difference is that direct speech, as prose in general, consists of pieces of infor-

mation conveyed in a sequence, while poetry communicates segments of information in paral-

lelism. The result is linear vs. segmental communication.

3

As a consequence, poetry is able to

switch from one temporal axis to another even more freely than direct speech. This results in a

greater variety of, and more abrupt transition from, one verbal form to another.

If so, it is inappropriate to smooth the asperities of a text as far as the verbal forms are

concernede.g., by translating everything with present tense except the cases where a different

time reference is clearly implied. We should rather do our best to carefully consider the verbal

forms and to interpret them in a consistent way. On the other hand, the difference between prose

and poetry may help understand some peculiarities in the functioning of the verbal system in the

latter. With this approach, the analysis of poetry becomes much more difficult but, as I think,

more respectful of the text and more fruitful.

1.1. Alternating Qatal/Yiqtol

Two main approaches to BH poetry can be mentioned. Most scholars fairly disregard the

verbal forms appearing in the texts and translate according to their own understanding, while

some assume archaic peculiarities in the use of verbal forms, especially an alternating occur-

rence, or variation, of qatal and yiqtol for the same event or information. This phenomenon has

been studied, among the first, by U. Cassuto and M. Held in the sixties-seventies on the basis of

Ugaritic and archaic Hebrew poetry. W. Moran also widely contributed to illustrating the

Northwest Semitic background of Hebrew. S. Gevirtz further suggested that the conjugational

variation qatal/yiqtol is a Canaanite peculiarity, also found in the Amarna letters.

4

In recent

years, a rather influential assessment of the situation following the pioneer research of W.

Moran is due to A.F. Rainey.

5

In principle, I would observe that, first, a phenomenon of a given language can not

automatically be applied to another language without appropriate control within the framework

of the verbal system of that language. Second, one should expect different verbal forms to play

different functions and analyze the texts accordingly on a synchronic level, rather than make the

analysis depend on comparative, diachronic considerations. Of course, diachrony is not ex-

cluded but one should make appropriate use of it, and in any case synchrony is crucial.

Now, in BH x-yiqtol and w

e

qatal occur along with qatal and wayyiqtol in prose texts re-

3

ferring to the past not only in historical narrative but also in direct speech (see table in 1

above). Besides, w

e

qatal and wayyiqtol are not equivalent to the respective nude verbal forms

plus a prefixed waw. In other words, w

e

qatal is not the coordinate continuation form of qatal,

nor is wayyiqtol the coordinate continuation form of yiqtol; rather, in direct speech w

e

qatal is

the coordinate continuation form of discourse-initial indicative x-yiqtol, while wayyiqtol is the

coordinate continuation form of discourse-initial qatal or x-qatal. As a consequence, coordinate

waw with finite verbal forms does not have a place in BH syntax despite the common opinion of

the grammarians.

6

This situation is peculiar to BH as compared, e.g., to Ugaritic.

7

1.2. Yiqtol in the First Place of the Sentence

Besides the variation qatal/yiqtol ( 1.1), a second major problem concerns yiqtol.

8

Ac-

cording to the theory presented here, sentence-initial yiqtol is volitive, or jussive, even though

its vocalization is not distinctively jussive or is not jussive at all. The problem is that a volitive

meaning is not always clearsometimes it may even appear excluded, e.g., when it refers to the

past. Yet, the clear cases that are abundantly available and the consistency of the verbal system

encourage us to consider this issue seriously because, of course, the exact intention of the texts

is at stake.

This problem is seen differently by those scholars who, on the one side, regard as jussive

only the verbal forms morphologically marked as such, and by those who, on the other side, re-

gard as jussive also the sentence-initial yiqtol forms. A further problem arises, as already men-

tioned, when the context is past. A comparative, widely accepted solution is to regard jussive

yiqtol, or short prefix conjugation, occurring in a past context as a survival of ancient Canaanite

yaqtul, and the long form as survival of the ancient Canaanite imperfect yaqtulu (see no. 5

above).

In my view, a correct solution takes into account the distinctiveness and reciprocal rela-

tionships of verbal forms in BH direct speech in prose texts in the different temporal axes. First,

I think that morphology is not a sufficient criterion to identify volitive or jussive yiqtol forms

because, on the one hand, in many cases such verbal forms are not distinguishable from the in-

dicative ones and, on the other, morphology is not always rigorously respected even where dis-

tinctive verbal forms are possible.

9

Second, sentence-initial position alone identifies a yiqtol as

jussive, although second-place jussive x-yiqtol are also clearly attested.

10

4

The synchronic solution that I am proposing is based on the contention that the BH ver-

bal system attested in direct speech in prose basically applies to poetry.

11

From the table above,

it follows that a narrative yiqtol corresponding to the jussive yaqtul typically used in Ugaritic

poetic narrative is not attested in BH. In BH, yiqtol does not narrate, i.e., it is not employed to

convey historical information in the main line; it is only used to comment, specify, detail, or de-

scribe an event in some way. The absence of a narrative yiqtol in BH combined with the ab-

sence noted above of inverted/converted verbal forms in Ugaritic makes me suspicious of any

quick comparison between the two verbal systems.

A major problem in this connection is to identify the temporal reference of yiqtol in the

different occurrences since, as indicated above, it can refer to the axis of the future as well as to

that of the past. In the former case, indicative yiqtol corresponds to the future tense of the Latin

languages, while in the latter it corresponds to the imperfect tense of the same languages. Jus-

sive/volitive yiqtol, on its part, mostly refers to the axis of the future, but occasionally is also

found in the axis of the past, and in the latter case it signals finality ( 2.4 below).

2. Analysis of Poetic Texts

In the following exposition I will try to illustrate the different functions of the two syn-

tactic constructions mentioned above, i.e., variation qatal/yiqtol, and first-place yiqtol. From

what has already been said, it follows that in BH one should speak, on the one side, of verbal

forms of the past axis rather than simply of qatal, because also wayyiqtol is attested, and, on the

other side, of verbal forms of the future axis rather than of yiqtol alone because w

e

qatal and

w

e

yiqtol are also attested. I will suggest that, first, qatal and yiqtol may refer each to its specific

time axispast and future, respectivelyand therefore simply represent a shift from past to

future information ( 2.1); second, when both qatal and yiqtol refer to the axis of the past, they

signal a shift from main-line, punctual information (qatal) to secondary-line, repeated/habit-

ual/explicatory/descriptive information (yiqtol) ( 2.2); third, sentence-initial yiqtol can be

functionally a non-initial yiqtol, i.e., a <x->yiqtol, because of a double-duty modifier ( 2.3);

fourth, sentence-initial yiqtol plays volitive function ( 2.4); and fifth, volitive yiqtol can play

the function of protasis ( 2.5).

5

2.1. Variation Qatal/Yiqtol with Reference to Past/Future

In some Psalms the variation, or alternating occurrence of (a) qatal or (a) continuation

wayyiqtol/(b) indicative x-yiqtol epitomizes a past intervention of God as the basis for the

psalmists hope for a similar intervention in the future. See Psa 4:4:

12

(a) cc:: But know that the lord has set apart the godly for himself;

(b) :::: the Lord will hear me when I will call to him.

13

Similarly in Psa 6:9-10:

:c::::c

(9)

Depart from me, all you workers of evil,

(a) :::::: for the Lord has heard the sound of my weeping.

(a) ::::::

(10)

The Lord has heard my supplication;

(b) :c: the Lord will accept my prayer.

The variation from (a) qatal or (a) continuation wayyiqtol to (b) x-yiqtol refers to dif-

ferent pieces of information both in Psa 4:4 and in 6:9-10 and the meaning is that Gods favor in

the past is the basis of confidence for the future. However, when that variation refers to the

same piece of information, it creates a kind of merismus

14

and the meaning is that what hap-

pened in the past will also happen in the future. See, e.g., Psa 8:6-7 (Engl. 8:5-6):

(a) ::c::c:

(6)

You have made him little less than God,

(b) c:::: and with glory and honor will you crown him

(b) :::::::

(7)

<you> shall give him dominion over the works of thy hands;

(a) :::::: everything you have put under his feet.

Because ::: in v. 7 parallels a waw-x-yiqtol construction in the previous line, it is

most probably to be analyzed as a similar construction with an elliptic element, maybe a pro-

nominal subject, i.e., <x-> yiqtol (see 2.3 below). Note the pattern past-future (a-b) // future-

past (b-a) in the sequence of the verbal forms.

The reverse occurrence (b) x-yiqtol/(a) qatal is also attested. See, e.g., in Psa 9:8:

(b) :::: But the Lord will sit enthroned for ever;

(a) c:cc:::: he has established his throne for judgment.

The psalmist states that the Lord is going to judge the world and he has already set up his

throne (as previously stated in v. 5). Contrast: But the Lord sits enthroned for ever, he has es-

tablished his throne for judgment (RSV), or But the Lord abides forever; He has set up His

throne for judgment (JPS).

6

Indeed, as I have tried to show elsewhere,

15

the whole Psa 9 is structured in three levels

of communication established by specific verbal forms: the level of prayer, with volitive

formsimperative and jussive yiqtol; the level of Gods action in the past, mostly with qatal;

and the level of the consequences for the just and the wicked, mostly with x-yiqtol. This dy-

namic three-level structure continues in the following Psa 10, which constitutes a unit with

Psalm 9 (see the LXX). The aim of this composition is to show that just as God intervened in

the past in favor of the poor, the same he will do in the future, and this faith constitutes the basis

of the prayer.

16

2.2. Variation Qatal/Yiqtol with Reference to Past

As already mentioned, in BH the phenomenon of the variation of (a) qatal/(b) indicative

yiqtol concerns not only these two verbal forms but also their continuation forms (a) way-

yiqtol and (b) w

e

qatal. A good example is Psa 78 which shows different such cases. Let us be-

gin with vv. 12-15:

(a) c:::::::

(12)

In the sight of their fathers he wrought marvels

::::::: in the land of Egypt, in the fields of Zoan.

(a/a) ::::::

(13)

He divided the sea and let them pass through it,

(a) ::::::: and made the waters stand like a heap,

(a) :::::::

(14)

and led them with a cloud in the daytime,

::: and all the night with a fiery light.

(b) :::::::

(15)

By cleaving (<While he> was cleaving) rocks in the wilderness,

(a) :::::: he gave them drink abundantly as from the deep.

V. 12 opens with (a) x-qatal, which is a usual way of starting an oral narrative. This is

followed by a parallel (a) qatal in v. 13actually, both x-qatal and initial qatal are attested at

the start of an oral narrative to begin the main line of communication in the past (see table in 1

above). The main line goes on with continuation (a) wayyiqtol in vv. 13-14. Then there

comes, as a surprise, a (b) first-place yiqtol in v. 15. The surprise is actually double: first be-

cause yiqtol used with past reference indicates repetition, habit, explication or description, while

both qatal and wayyiqtol indicate punctuality; second, because first-place yiqtol has volitive

function (see table in 1 above).

The translation above assumes that the sentence-initial yiqtol in v. 15 is not volitive but

actually an elliptic indicative <x-> yiqtol construction (see 2.3. below). However, before ex-

plaining this analysis let us get a broader picture of the situation by considering other cases oc-

7

curring in Psa 78. Indeed, the sequence of the verbal forms in vv. 25-26 is similar to that of the

previous passage, i.e., (a) x-qatal in v. 12 and (b) <x-> yiqtol and (a) wayyiqtol in v. 15, as is

that of vv. 46-47:

(a) :::::

(25)

(a) ::c:

(46)

(a) :::::: ::::

(b) ::::::c

(26)

(b) ::c::::

(47)

(a) :::::: :::::::

(Psa 78:25) Man ate of the bread of the angels; / he sent them food in abundance. / (26) By caus-

ing (<While he> was causing) the east wind to blow in the heavens, / he led out by his power the

south wind.

(46) And he gave their crops to the caterpillar, / and the fruit of their labor to the locust, / (47)

<while he> was destroying their vines with hail, / and their sycamores with frost.

Another sequence in Psa 78 is (a) wayyiqtol/(b) x-yiqtol in vv. 29 and 36 along with

(b) <x-> yiqtol, (a) negative qatal and (a) x-qatal in vv. 49-50:

(a/a) :::::

(29)

(a) :c::c

(36)

(a) :::::c

(48)

(b) ::::: (b) :::::: :c::::

(b) c:::

(49)

:::::

:::::::

(b) c:::cc

(50)

(a) ::c:::::

(a) :c:::

(Psa 78:29) And they ate and were well filled, / indeed, what they craved he was giving them.

(36) Then they flattered him with their mouths, / while with their tongues they were lying to him.

(48) Then he gave over to the hail their cattle, / and their flocks to thunderbolts. / (49) By letting

loose (<While he> let loose) on them his fierce anger, / wrath, indignation, and distress, / a

company of destroying angels; / (50) by making (<while he> made) a path for his anger, / he did

not spare them from death, / while their lives to the plague he gave over.

A third sequence in Psa 78 is similar to the previous two, i.e., (a) wayyiqtol/(b) x-yiqtol

in v. 44 and (b) <x-> yiqtol/(a) wayyiqtol in v. 45:

(a) ::c

(44)

Then he turned to blood their rivers,

(b) ::::: while as a result of their streams they were not able to drink any more;

(ba) :::::::

(45)

By sending (<Since he> was sending) among them swarms of flies,

they devoured them,

(/a) :::::c: and frogs, they destroyed them.

These passages (also see Psa 78:34-40) show rather clearly the descriptive/habitual/ex-

plicatory/descriptive function of x-yiqtol (along with its continuation form w

e

qatal) and its

8

negative counterpart (b) :/ + yiqtol in a past context. They also show by contrast the punc-

tual value of (a) qatal, of its continuation form (a) wayyiqtol (and their negative counterpart

+ qatal).

What I am saying means that the line of information with x-yiqtol/w

e

qatal does not stand

on the same level with the line of information with qatal/wayyiqtol but the former is subservient

to the latterit specifies it in different ways according to various context situations.

17

Above, I

rendered Psa 78:44 as follows: Then he turned [wayyiqtol] to blood their rivers, / while as a

result of their streams they were not able to drink any more [x-negative yiqtol]. The first sen-

tence conveys a single/punctual piece of historical information while the second expounds the

ensuing continuous situation, i.e., the first narrates (foreground), the second describes (back-

ground). Other similar cases in Psa 78 are as follows:

(v. 20) ::::: Behold, he smote the rock and water gushed out,

cc::: indeed, streams were overflowing.

(v. 58) :::::c:: And they provoked Him to anger with their high places

:cc:: indeed, <they> were constantly moving him to jealousy with

their idols.

(v. 64) c::::: Their priests fell by the sword,

::::::: while their widows were making no lamentation.

(v. 72) ::::::: And (David) tended them according to his upright heart,

::c:::::: while with his skilful hands he was guiding them.

2.3. First-Place Yiqtol as <x-> YiqtolDouble-Duty Modifier

More difficult to explain in the framework of my proposal are the cases with sentence-

initial yiqtol, which in prose texts has volitive force but in several poetic passages referring to

the past volition is unlikely. One could, of course, suppose that specific poetic criteria, such as

prosody or rhythm, might allow some flexibility in the otherwise rigid word order of BH prose.

However, it seems to me that such poetic criteria are fairly elusive and maybe impossible to de-

fine.

A more verifiable characteristic of poetry is ellipsis, i.e., the omission of a given element

that is grammatically expected. In poetry, this phenomenon is particularly frequent, especially in

the form of a technique called double-duty modifier. This designates a grammatical element

that serves two or more lines although it does not appear in every case but only in the first line

or, more difficult to recognize, only in the subsequent parallel lines of a poetic unit.

18

A clear

9

case is Psa 2:1-2:

19

(1a) :::: :

(1)

Why did the nations conspire,

(1b) ::: while the peoples were plotting in vain?

(2a) :::::

(2)

< > <Why> were the kings of the earth setting themselves,

(2b) c::: while the rulers took counsel together,

:::: against the Lord and his anointed?

Initial : modifies not only the qatal immediately following but also the yiqtol of v.

2a,

20

while the x-yiqtol in v. 1b and the x-qatal in v. 2b are circumstantial constructions (back-

ground) linked each to its preceding verbal form (foreground). Actually, we discover a chiastic

disposition of the verbal forms, i.e., in v. 1 qatal-yiqtol // yiqtol-qatal in v. 2. The yiqtol con-

structions convey repetition/habit/explication/description and do not stand on the same level

with the qatal constructions, which convey single information. In combination with the chiastic

disposition of the elements, the alternation of qatal and yiqtol is likely intended to add depth of

field to the presentation of the event. In my opinion, this relief function is likely to be a mean-

ingful explanation for the phenomenon of the alternation qatal/yiqtol in general, even when no

chiastic pattern is attested (see 3 below).

21

The solution of a double-duty modifier, however, does not seem to apply in cases where

no common element is available, e.g., in Psa 78:15, 26, 45, 49, 50, 58 analyzed above ( 2.2). I

would suggest as a suitable solution the ellipsis of a pronominal subject in these and similar

cases. e.g., in Psa 78:44 as it were : <>. This analysis is supported by a chiastic paral-

lelism, i.e., wayyiqtol (main event, foreground) + x-yiqtol (result, background) in 78:44 // <x->

yiqtol (cause, background) + wayyiqtol (main event, foreground) in 78:45.

The best model I can find for the ellipsis of a pronominal subject is Psa 9:9:

::::cc: And he [i.e., the Lord] will judge the world with righteousness,

:::::: <he> will judge the peoples with equity.

One may suggest that the omission of a pronominal subject is intended to speed up the

parallelism. Let us consider the following examples in which yiqtol refers to the future:

(Psa ::: All who see me will mock at me

22:8) :::c::cc will make mouths at me, will wag their heads.

(Hab cc:::: Their horses will be swifter than leopards,

1:8) :::: they will be more fierce than the evening wolves,

:c:c and their horsemen will press proudly on;

10

:::c indeed, their horsemen from afar will come

:::::c: will fly like an eagle swift to devour.

22

(Psa ::c:: On the lion and the adder you will tread

91:13) ::c:c:: will trample under foot the young lion and the serpent.

For the cases where yiqtol refers to the past, Driver, like H. Ewald and others, assumed

an ellipsis of <way->.

23

Yet, I prefer a different kind of ellipsisthat of a pronominal sub-

jectthat is in keeping with the usual values of yiqtol in BH. On the one side, as already men-

tioned, sentence-initial jussive yiqtol plays totally different functions from narrative wayyiqtol,

although the latter is usually composed of a short-form yiqtol. On the other side, clear cases of

x-yiqtol constructions are attested indicating repetition/habit/explication/description in the axis

of the past, in parallelism with wayyiqtol and qatal forms. In my view, this situation also renders

improbable the other solution mostly favored today, i.e., that initial yiqtol is simply an archaic

remainder of the Canaanite narrative yaqtul.

24

2.4. Volitive Functions of Yiqtol

In many cases initial yiqtol and its continuation form w

e

yiqtol clearly play a volitive

function as expected, e.g., in Psa 9:2-3 (Engl. 9:1-2):

:::

(2)

I want to give thanks to the Lord with my whole heart,

:c::cc I want to tell of all your wonderful deeds.

:::::

(3)

I want to be glad and exult in you,

:::: I want to sing praise to your name, O Most High.

25

Besides cases like this in which yiqtol occurs the first place of the sentence, there are

cases in which (1) first-place yiqtol and (2) second-place x-yiqtol forms alternate though clearly

being both volitive. The difference is one of level of communication(1) main level, or fore-

ground, vs. (2) secondary level, or background. Consider Psa 20:2-6 (Engl. 20:1-5):

(1) :::::

(2)

(1) ::::

(5)

(1) ::::::: (2) :::::

(1) ::::

(3)

(1) :::::::

(6)

(2) :c:: (2) ::::::

(1) :::::

(4)

(1) :::::

(2) ::::

(Psa 20:2) May the Lord answer you in the day of trouble! / May the name of the God of Jacob

protect you! / (3) May he send you help from the sanctuary, / while from Zion may he give you

support! / (4) May he remember all your offerings, / while your burnt sacrifices may he regard

with favor! / (5) May he grant you your hearts desire, / while all your plans may he fulfil! / (6)

11

May we shout for joy over your victory, / while in the name of our God may we set up our ban-

ners! / May the Lord fulfil all your petitions!

More rarely but clearly, yiqtol plays volitive function also in contexts referring to the

past, in which cases it expresses finality. In prose this function is mostly played by w

e

yiqtol (and

by waw-x-yiqtol as well).

26

It is a characteristic of poetry that also nude initial yiqtol, i.e.,

without prefixed waw, can play this function.

27

Let us consider 2 Kgs 19:23-25 (// Isa 37:24-26),

a passage from an oracle against Sennacherib in which God first puts words into the mouth of

Sennacherib, then addresses him directly:

28

(23a) :::::::::: ()

(23)

() I have ascended the height of the mountains, the

uttermost part of Lebanon,

(23b) :::::::: that I may cut down the tallness of its cedars, the choice

of its cypresses,

(23c) :::::: and that I may come to the shelter of its border, to the

forest of its orchard.

(24a) ::::::::

(24)

I have dug so that I could drink foreign water,

(24b) :::::c::: that I may dry up with the sole of my feet all the rivers of

Egypt!

(25a) :::::::::

(25)

Have you not heard? Long ago I have done this,

(25b) ::::: from old days I was planning it;

(25c) :::: now I have brought it to pass,

(25d) :::::::: that there may be destroyed into waste heaps

(25e) ::::: fortified cities.

In vv. 23b-c, 24b, and 25d, instead of w

e

yiqtol, the ancient versions read wayyiqtol forms

because they translate with past tenses. However, the volitive forms of the MT can be inter-

preted as conveying the purpose of the two main pieces of information expressed with x-qatal

(vv. 23a, 24a and 25c).

29

One could, of course, as most scholars do, vocalize the text differently,

translate the verbal forms with past tenses and be satisfied with that; still, in my opinion the

problem remains of why did the Masoretes vocalize that way and what they intended.

30

2.5. Protasis Function of Volitive Yiqtol

As already noted by classical grammarians, sentence-initial jussive yiqtol can play the

function of the protasis.

31

One good example is Psa 139:8-10:

32

(8a) ::::::c: If I should ascend to heaven, you are there;

(8b) :::: should I make Hades my resting-place, there you are.

(9a) :c::: Should I raise the wings of the morning,

12

(9b) :::::: should I settle at the extremity of the sea,

(10a) ::::::: even there let your hand guide me,

(10b) :::: and let your right hand lay hold of me.

The first protasis in v. 8a is explicit (with : + yiqtol) while the second in v. 8b (with

volitive w

e

yiqtol, ::), the third in v. 9a and the fourth in v. 9b (with sentence-initial volitive

yiqtol, : and :::, respectively) are implicit protases, simply with volitive verbal forms.

33

Similar cases are Psa 46:3-4 (Engl. 46:2-3); 91:7; 93:3-4; 146:4:

(46:3a) ::::: Therefore we will not fear though the earth should change

(3b) :::::c:: and the mountains shake in the heart of the sea;

(4a) :::: should its waters roar and foam,

(4b) :::::: should the mountains tremble with its tumult.

34

(91:7) ::c Should a thousand fall at your side

(7b) ::::: and ten thousand at your right hand,

(7c) :: none will reach you.

(93:3a) :::: The floods have lifted up, O Lord,

(3b) ::::: the floods have lifted up their voice.

(3c) ::::: Should the floods lift up their roaring,

(4a) :::::: more than the thunders of many waters,

(4b) ::::: of the mighty ones, of the breakers of the sea,

(4c) ::: mighty is the Lord on high!

35

(146:4a) :::::: When his breath will depart, he will return to his earth;

(4b) :::::::: on that very day his plans will have perished.

36

3. Conclusion Poetic Peculiarities

In BH the different verbal forms play basically the same functions in poetry as in prose,

specifically in direct speech (see 1 above). I do not see any justification for taking qatal and

yiqtol as equivalent verbal forms and translate them in the same way. This also applies to their

respective continuation formswayyiqtol and w

e

qatal (indicative) or w

e

yiqtol (volitive). I think

that:

(3.1) Qatal/wayyiqtol are to be translated with the simple past tense, and indicative x-

yiqtol/w

e

qatal with the future. This supposes the fact that each group of verbal forms refer to its

own temporal axis, i.e. qatal/wayyiqtol to the axis of the past, x-yiqtol/w

e

qatal to the axis of the

future ( 2.1).

(3.2) When x-yiqtol/w

e

qatal alternate with qatal/wayyiqtol and refer to the axis of the

past, the former indicate repeated/habitual/explicatory/descriptive information (background)

13

while the latter punctual/single information (foreground) ( 2.2).

(3.3) Sentence-initial yiqtol (occasionally also x-yiqtol) and its continuation form w

e

-

yiqtol convey volitive information. Occasionally they also appear with reference to the past axis

to indicate purpose (volitive consequence) ( 2.4). Sentence-initial volitive yiqtol is also well

attested with the function of protasis ( 2.5).

Further, certain guidelines are to be followed in order to arrive at a correct analysis. On

the one hand, the functions of the verbal forms are to be evaluated in the framework of the text.

Much too frequently passages are analyzed in isolation, with little or no consideration of their

context. On the other hand, the peculiarities of poetry are to be considered.

What makes poetry different from prose, even from direct speech, is its segmental char-

acter ( 1). In other words, poetry develops by segments of information disposed in parallel

lines rather than by coordinate pieces of information linked in a linear sequence. Thus certain

peculiarities become understandable. First, in poetry a sequential verbal form like wayyiqtol is

much less frequent than in prose. Second, when it appears, usually as a continuation form of

initial (x-)qatal, wayyiqtol is found in alternation with x-yiqtol and w

e

qatal. Third, the phe-

nomenon of a double-duty modifier is much more attested in poetry than is in prose.

I call merismus the alternating occurrence of qatal/yiqtol in poetry. It comprises two

forms according to different coordinates: qatal for past vs. yiqtol for future information when

each verbal form refers to its specific temporal axis ( 2.1); and qatal for narrative-punctual vs.

yiqtol for habitual-descriptive information when both verbal forms refer to the axis of the past

( 2.2). Merismus is a way of expressing totality in abbreviated form. Here, the coordinates past

vs. future are intended to express totality, perpetuity while the coordinates punctuality vs.

habit/description add depth perspective and contribute to a graphic representation of the events

that is characteristic of poetry.

Indeed, the fact that a tense transition from qatal/wayyiqtol to x-yiqtol/w

e

qatal with past

reference is frequent in poetry while it is rare in prose reflects a characteristic attitude of the

poet vs. the historian towards past events. While the historian narrates past events in a sequence

of successive bits of information conveyed by a chain of coordinated wayyiqtol, the poet cele-

brates them with frequent resort to description, or graphic representation of multiple bits of in-

formation that follow one another in parallel lines. This is obtained by a recurring shift from

verbal forms of punctual information qatal/wayyiqtol to verbal forms of habitual, descriptive in-

14

formation (x-)yiqtol/w

e

qatal.

The phenomenon of the double-duty modifier helps detect the exact function of appar-

ently sentence-initial yiqtol forms that are actually second-place <x-> yiqtol constructions (

2.3).

In several cases where yiqtol/w

e

qatal verbal forms occur along with qatal/wayyiqtol it is

not easy to decide whether the yiqtol/w

e

qatal refer to the axis of the future and are to be trans-

lated with future tense ( 2.1), or to the axis of the past and are to be translated with the imper-

fect ( 2.2). Sentence-initial yiqtol and w

e

yiqtol can express finality in the axis of the past (

2.4). Only close attention to the context at large can help decide.

One should also note that, particularly in poetry, second-place indicative yiqtol expresses

habitude, custom not only in the axis of the past, where it is a background verbal form ( 2.2),

but also in the axis of the future, where it is a main-line verbal form. In fact, in some cases i n-

dicative yiqtol is used to express habitual presentwhile actual present is usually expressed by

nonverbal sentence especially in proverbial sayings like, e.g., Prov 10:1-2:

(1) :::::: A wise son will always make glad his father,

::::c:: while a foolish son is a sorrow to his mother.

(2) ::::: Treasures gained by wickedness will never profit,

:::::: while righteousness will always deliver from death.

37

The issues presented here indicate a way of analyzing poetry in the framework of BH

verbal system in general, especially in direct speech. This analysis poses a challenge not easy to

face; however, I have tried to suggest that the effort is worthwhile. The result may be a fresh

interpretation of passages, even of complete Psalms.

38

The alternative, more common solution is to admit in BH poetry a narrative yiqtol as an

archaic residue of ancient Canaanite-Ugaritic yaqtul. However, on the one side, a phenomenon

of a given Semitic language, even a well established one, is not automatically applicable to an-

other language without proper control of how it fits within the verbal system of that language.

On the other side, there are two main differences between Ugaritic and BH verbal systems (cf.

1.2). First, the so-called inverted, or converted verbal forms are well attested in BH, both in

prose and in poetry, while they seem to be almost non existent in Ugaritic (cf. no. 7 above).

Second, jussive yiqtol with narrative function on the model of Ugaritic yaqtul does not have a

place in BH verbal system, nor has indicative x-yiqtol full narrative function, because it does

15

not convey main-line information in the past like qatal/wayyiqtol but rather off-line information

like w

e

qatal.

For these reasons, I think that the Semitic-comparative, diachronic solution is not suit-

able for BH poetry.

Footnotes

1

Syntax of the Verb in Classical Hebrew Prose (Sheffield 1990; originally published in Italian in

1986); Analysing Biblical Hebrew Poetry, JSOT 74 (1997) 77-93. Hereafter, well-known grammars are

quoted with the names of the authors/revisers only, i.e., Gesenius-Kautzsch, and Joon-Muraoka. The se-

ries Commentary on the Old Testament in Ten Volumes (ed. C.F. Keil - F. Delitzsch; Grand Rapids [MI],

repr. 1980-1981) is referred to as: Keil-Delitzsch.

2

A first attempt in this direction is a short study on the poetic section in the Book of Jonah (2:3-

10; see Syntactic Analysis of Jonah, Liber Annuus 46 [1996] 26-31, pp. 26-31). Another of my essays

concerns Psalms 9-10 (together with E. Cortese, Lattesa dei poveri non sar vana: Il Sal 9/10 attualiz-

zato, in Biblica et semitica. Studi in memoria di Francesco Vattioni [ed. L. Cagni; Napoli-Roma 1999]

129-149, pp. 139-149). Also see my analysis of Proverbs 22:17-24:22 published in three installments

(Proverbi 22,17-23,11, Liber Annuus 29 [1979] 42-72; Proverbi 23,12-25, ibid. 47 [1997] 33-56;

Proverbi 23,26-24,22, ibid. 48 [1998] 49-104), and Poetic Syntax and Interpretation of Malachi (to

appear in the same review, vol. 51 [2001]).

3

As I have tried to show by comparing Judg 4:19-21 and 5:25-27, two passages in which the

killing of Sisera at the hands of Jael is first narrated in prose, then celebrated in poetry (see Analysing

Biblical Hebrew Poetry, 78-80).

4

U. Cassuto, The Goddess Anath. Canaanite Epics of the Patriarchal Age Texts, Hebrew

Translation, Commentary and Introduction (Jerusalem 1971; Hebr. orig. 1951), 46-48; M. Held, The

Yqtl-Qtl (Qtl-Yqtl) Sequence of Identical Verbs in Biblical Hebrew and in Ugaritic, in Studies and Es-

says in Honor of Abraham A. Neuman President, Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning,

Philadelphia (ed. A.A. Neuman - M. Ben-Horin - B.D. Weinryb - S. Zeitlin; Leiden 1962), 281-290; S.

Gevirtz, Evidence of Conjugational Variation in the Parallelization of Selfsame Verbs in the Amarna

Letters, JNES 32 (1973) 99-104.

5

A.F. Rainey, The Prefix Conjugation Patterns of Early Northwest Semitic, in Lingering over

Words. Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Literature in Honor of William L. Moran (ed. T. Abusch - J.

Huehnergard - P. Steinkeller [Atlanta, GA, 1990] 407-420; more recently in Canaanite in the Amarna

Tablets: A Linguistic Analysis of the Mixed Dialect Used by the Scribes from Canaan, vols. 1-4 [Leiden

1996]). For a discussion of Raineys position, particularly by J. Huehnergard and E.L. Greenstein, see

16

Symposium: The yiqtol in Biblical Hebrew, HS 29 (1988) 7-42 (with contributions by E.L Greenstein,

J. Huehnergard, Z. Zevit, and A.F. Rainey himself). See more recently P.J. Gentry, The System of the

Finite Verb in Classical Biblical Hebrew, HS 39 (1998) 7-39; J. Joosten, The Long Form of the Prefix

Conjugation Referring to the Past in Biblical Hebrew Prose, HS 40 (1999) 15-26; T.D. Andersen, The

Evolution of the Hebrew Verbal System, ZAH 13 (2000) 1-66; J.A. Cook, The Hebrew Verb: A Gram-

maticalization Approach, ZAH 14 (2001) 117-143.

6

In his treatment of archaic BH poetic texts on the basis of Ugaritic, U. Cassuto maintained that

in Isa 60:16 Ww conversive [i.e. consecutive] () in effect does not alter the sense at all, and that

particularly from this passage in Amos [i.e., 7:4, AN] it can be seen that the Ww does not convert

anything. This enables us to ascertain the origin of this Ww, and to understand correctly the form of

verses like Genesis i 5 (The Goddess Anath, 46, and no. 39). Now, in Isa 60:16 we find in parallel

lines w

e

qatal and x-yiqtol, which are perfectly compatible verbal forms because the first is the usual main-

line verbal form for the future axis and the latter its usual off-line counterpart in the course of direct

speech (see 1 above); in this case, therefore: You shall suck the milk of nations (: : : ::), / even

the breast of kings you shall suck (:: ::: :). Things are more complicate in Am 7:4 because it

comprises wayyiqtol and w

e

qatal that are not homogeneous verbal forms but the former signals main line

and single event in the past while the latter signals, when it refers to the axis of the past, off line and

repetition/habit/description/specification (see 2.2 below); in this case: and (the fire) devoured the great

deep (: : :: : :), / while it was eating up the land (: :). In any case, the waw does

convert the BH verbal forms, or better, w

e

qatal and wayyiqtol are individual verbal forms as such because

they possess distinctive morphology and distinctive functions. Cassutos position regarding waw was

shared by M. Held, The Yqtl-Qtl (Qtl-Yqtl).

7

It is commonly held that the so-called inverted verbal forms do not exist in Ugaritic poetic

texts while they exist in later prose texts. Thus already C.H. Gordon, who however noted that Ug[aritic]

poetry has one clear case of qtl with w conversive (67 : I : 24) (Ugaritic Textbook Grammar,

Texts in Transliteration, Cuneiform Selections, Glossary, Indices [Roma 1965] 115, 13.29). More re-

cent grammars like that of S. Segert (A Basic Grammar of the Ugaritic Language, With Selected Texts

and Glossary [Berkeley - Los Angeles - London 1984]), E. Verreet (Modi ugaritici: Eine morpho-

syntaktische Abhandlung ber das Modalsystem im Ugaritischen [Leuven 1988]), and D. Sivan (A

Grammar of the Ugaritic Language [Leiden - Boston - Kln 1997]), do not address the issue of inverted

verbal forms. J. Tropper, on the one side, mentions a few cases of verbal formations that typologically

resemble the Perfectum consecutivum of BH grammar (Ugaritische Grammatik [Mnster 2000] 716,

76.541); on the other side, he states: Geht der PK

K

i [i.e., the indicative short-form yqtl] die Konjunktion

w (und) voraus, ndert sich ihre aspektuell-temporale Funktion nicht. Eine Differenzierung zwischen

PK

K

i einerseits und w-PK

K

i anderseits ist im Ug. nicht notwendig und sachlich nicht sinnvoll (pp. 695-

17

696). However, in his review of Segerts grammar A.F. Rainey suggested that The ubiquitous examples

of the short form *ny in poetic contexts after the w conjunction remind one of the narrative preterite con-

tinuative of biblical Hebrew (A New Grammar of Ugaritic, Or 56 [1987] 391-402, p. 398).

8

S.R. Driver wrote what is until today one of the most accurate treatment on the use of the jus-

sive form (A Treatise on the Use of the Tenses in Hebrew and Some Other Syntactical Questions [Ox-

ford 1892] 170-175; see esp. 170, p. 212). Driver stressed the need of not disregarding the morphol-

ogy of the jussive. Some clear cases of jussive vs. indicative yiqtol forms have been discussed recently by

A. Shulman (The Function of the Jussive and Indicative Imperfect Forms in Biblical Hebrew Prose,

ZAH 13 [2000] 168-180). Like Driver, Shulman only considers the verbal forms that are morphologically

identified as jussive; she does not seem to consider the initial position of yiqtol to be a mark of the jussive

character of the verb although she mentions E. Qimron and P. Gentry (pp. 168-169) who emphasize the

importance of the initial position of yiqtol in the sentence. E. Qimron also stresses the importance of the

initial position of yiqtol although his approach to syntax is different from mine (A New Approach to-

ward Interpreting the Imperfect Verbal Forms in Early Hebrew, Lonnu 41 [1998] 31-43).

9

Consult, e.g., Joon-Muraoka 114gN, and my Syntax of the Verb, 55.

10

On these issues, see my Syntax of the Verb, 55, and my paper, A Neglected Point of Hebrew

Syntax: Yiqtol and Position in the Sentence, Liber Annuus 37 (1987) 7-19.

11

According E.L. Greenstein, poetry is direct discourse (Direct Discourse and Parallelism, in

Studies in Bible and Exegesis, vol 5 [Ramat-Gan 2000; Hebr.] 33-40; Engl. abstract on p. VII; and Be-

tween Ugaritic Epic and Biblical Narrative: The Role of Direct Discourse, in Annual Meeting of the So-

ciety of Biblical Literature [Atlanta, GA, 1993]). For my part, I will suggest that BH poetry, as maybe

poetry as such, shows a dramatic character in the use of the verbal forms ( 3 below), i.e., it describes

or celebrates an event rather than simply narrating it as does prose ( 1 and no. 3).

12

Unless explicitly indicated, the English translations are taken from the RSV with modifications.

13

Contrast M. Dahood, who translates both verbal forms with the future: Yahweh will work

wonders Yahweh will hear me and notes: Perfect hiplh is balanced by imperfect yim, a very

common sequence in Ugaritic and Hebrew poetry (Psalms I, 1-50 Introduction, Translation and Notes

[New York 1966] 24). Among good examples of this phenomenon Dahood lists Psa 6:10, 9:8, and 93:3,

but I will propose a different analysis (see 2.1 and 2.5 below).

14

On this phenomenon in poetry, consult W.G.E. Watson (Classical Hebrew Poetry. A Guide to

Its Techniques [Sheffield 1984] 321-324). F. Rundgren called merismus the shift from wayyiqtol to waw-

x-qatal found in Gen 1:5 (Das althebrische Verbum [Stockholm-Gteborg-Uppsala 1961] 103; see no. 6

above). I would rather reserve this designation to cases in which the same item is referred to with both

past and future verbal forms in parallelism. A similar case of merismus is when a given item is referred to

in parallel lines as punctual information with qatal/wayyiqtol and as repeated/habitual/explicatory/de-

scriptive information with yiqtol/w

e

qatal (see 2.2 and 3 below).

18

15

In my paper, Lattesa dei poveri non sar delusa, 139-140.

16

I would insist on this point: if we do not care to take the verbal forms seriously, we run the risk

of missing the dynamic and precise intention of many Psalms and other poetic materials. E.g., the alter-

nation qatal/jussive yiqtol and w

e

yiqtol is a characteristic structuring device of Psa 85. Indeed, we find

qatal in vv. 2-4; prayer with imperative, then indicative x-yiqtol, and again imperative in vv. 5-8; prayer

with jussive yiqtol, then a non-verbal sentence (present tense), qatal, and again jussive yiqtol in vv. 9-14.

Note that the constructions x-yiqtol in vv. 13-14 are jussive because they are followed by ::. which is a

jussive w

e

yiqtol formation with distinctive morphology. See on this my paper, A Neglected Point of He-

brew Syntax, 9-10.

17

Rainey quoted Judg 21:25 as an example of yiqtol expressing continuous action in the past,

which is one of the function of imperfect yaqtulu of the el-Amarna letters from Byblos (The Prefix

Conjugation Patterns, 411-412). This is certainly correct; note, however, that this is a descriptive rather

than a narrative function of yiqtol. In other words, this yiqtolexpressing background, or secondary line

of communicationis not interchangeable with narrative wayyiqtolexpressing foreground, or main

line. See table of verbal forms in 1 above.

18

On ellipsis and various double-duty modifiers, consult Watson, Classical Hebrew Poetry, 303-

306. A large list of passages that in the authors opinion show this phenomenon in its various forms has

been drawn by M. Dahood, Psalms III, 101-150. Introduction, Translation and Notes (New York 1970)

428-444. Also see C.L. Miller, Patterns of Verbal Ellipsis in Ugaritic Poetry, UF 31 (1999) 333-372.

19

In Job 40:15-32 is also a good example. It can be subdivided into grammatical units on the ba-

sis of the particles that are used in the description of Behemoth: the presentative particle : behold in

vv. 15 and 16, its variant in v. 23, and the interrogative particle in vv. 26-29 and 31. The particle :

of v. 16 also affects the first-place yiqtol in vv. 17 and 22 as well as the intervening lines (vv. 19-21); the

particle also governs the following x-yiqtol (v. 24) and first-place yiqtol (v. 25); and finally the particle

also governs the first-place yiqtol of v. 30, which is the only one without that particle in vv. 26-31. For

his part, A. Gianto quotes Job 40:25-26 and then 40:26-28a without mentioning the governing particles

nor caring about the position of yiqtol in the sentencefirst or second. He assigns to the imperfect

forms in 40:25-26 an epistemic value and to those of 40:26-28a a deontic value (Mood and Modality

in Classical Hebrew, Israel Oriental Studies 18 [1998] 183-198, pp. 185-186). However, such semantic

specifications can hardly be the basis for syntactic analysis without the support of more objective criteria.

20

Cf. Hab 1:2: :: : / c: :/ :::: / ::: :: How long, o Lord, I

have cried for help, / and you will not hear? / <How long> shall I cry to you Violence! / and you will

not save?; 1:13: ::: : :: :::/ :: :: : c:: :Why will you look on faithless men,

<why> will you be silent / when the wicked swallows up the man more righteous than he?

21

Similar cases of double-duty modifiers are Psa 4:3 (Engl. 4:2), 88:15 (Engl. 88:14), and 139:13.

This phenomenon is more rarely attested in prose, e.g., Gen 15:15: As for yourself, you shall go

19

( :: :) to your fathers in peace; <and as for yourself> you shall be buried (:: <:>) in a good

old age.

22

A waw-x-yiqtol construction in the previous line ( : : :c) breaks the sequence of

three indicative future w

e

qatal. Its function is to describe the previous information (note the repetition of

the same subject, their horsemen, respectively at the end and the beginning of the two lines). I have

rendered this function with indeed. A <x-> yiqtol construction (c:) parallel to the preceding waw-x-

yiqtol speeds up the description. The hypothesis of ellipsis is supported here by the close sequence of two

parallel verbal forms belonging to the same subject at the end and the beginning of the respective lines

both here (: and c:) and in the next example, Psa 91:13 (: and c::).

23

Driver, Treatise 172-174.

24

Rainey quoted Deut 32:8 and 32:10 to prove that Biblical Hebrew poetry still employs yaqtul

as a Preterite (The Prefix Conjugation Patterns, 410). Actually, while :: (32:8) is morphologically

marked as jussive yiqtol, :: (32:10) is not. Further, a look at the text will show that other yiqtol

forms occur in 32:8-13 side by side with the two quoted by Rainey, and that one of them is morphologi-

cally marked as non jussive form, i.e., : in 32:11. In my view, this is a good case to show that the mor-

phology of yiqtol is not fully in agreement with the syntactic function; and this is the reason why I think

that morphology is not a sufficient criterion to distinguish jussive from indicative yiqtol, but the principle

of the initial position in the sentence is to be invoked as a more basic criterion (see no. 8 above). Further,

:: (32:8) is preceded by two circumstantial phrases in the same verse that can not be disregarded, i.e.,

:: : :: and : :: c:. This fact suggests, in my opinion, the correct analysis. The two cir-

cumstantial phrases function as an extraposed element, or protasis, and :: as the main sentence, or

apodosis (see similar constructions in my Syntax of the Verb, 102, esp. Exod 40:36 on p. 134). In other

words, the two prepositional phrases govern all the series of yiqtol forms in 32:8-13 and as such they act

as a kind of double- (or rather multi-) duty modifier. As a consequence, these yiqtol are not jussive in

function since they are not actually initial. They are not narrative, either. Indeed, they describe ( 2.3) or

represent the events graphically ( 3), rather than narrating them (see no. 11 above). Therefore, I would

translate Deut 32:8 and 10 as follows: (8) When the Most High portioned out the inheritance to the na-

tions, / when he separated the children of men, / he would fix (::, apodosis) the boundaries of the nations

/ according to the number of the sons of Israel / (10) Should he find him/When he would find him

(::, protasis, cf. 2.5 below) in the land of the desert, / and in the wilderness, the howling of the

steppe, / would surround him (:::c, apodosis), take care of him (:::, coordinate), / protect him

(::, coordinate) as the apple of His eye.

25

Psa 72, a prayer for the king, consists almost entirely of volitive forms.

26

See examples in Driver, Treatise 62-64, and 174.

27

The fact that I propose here a functional equivalence between volitive nude yiqtol and w

e

-

yiqtol does not oblige to accept the ellipsis of <way-> proposed by previous scholars for yiqtol in narra-

20

tive (see 2.3, no. 23 above). In fact, while yiqtol and w

e

yiqtol are homogeneous verbal forms, both be-

ing volitive, yiqtol and wayyiqtol are not because a narrative yiqtol does not exist in BH ( 1.1 above).

28

Translation adapted from Keil-Delitzsch, III/1, 450-452.

29

After x-qatal in v. 24a we find w

e

qatal, a verbal form that according to rule is not coordinate to

x-qatal but rather expresses a non-volitive consequence (rendered here with so that I could) or a cir-

cumstance as in v. 22: :c: :c :: Whom have despised while you were blaspheming? This

function of w

e

qatal contrasts that of w

e

yiqtol which expresses a volitive purpose (rendered here with that

I may). See table in 1, last row.

30

Given the fact that our knowledge of BH is basically dependent on the Masoretic redaction of

the Hebrew Bible, this problem can hardly be ignored. Even if we may prefer a different vocalization, the

task remains of trying to understand what the Masoretes meant by their reading. Further, we have to take

into account the fact that 2 Kgs 19:23-25 is not the only text in which we find qatal/wayyiqtol along with

yiqtol/w

e

yiqtol; see, e.g., Psa 104:14, 15, 20 (no. 38 below).

31

See, e.g., Gesenius-Kautzsch 108e-f; Joon-Muraoka 167a.

32

Translation adapted from Keil-Delitzsch, V, 342, 347.

33

A difference between the conditional sentences in v. 8 and those in vv. 9-10 is that both the

apodoses in v. 8 are non verbal clauses while those of v. 10 have volitive forms as the protases. The x-

yiqtol in v. 10a is also most probably a volitive construction because it is parallel with and coordinate to

an explicit volitive w

e

yiqtol in v. 10b; lit. Let me raise the wings of the morning, / let me settle at the

extremity of the sea; / even there, let your hand guide me, / and let your right hand lay hold of me (cf.

Joon-Muraoka 167a/2).

34

The function of the two volitive yiqtol in Psa 46:4 is similar to that of : in 93:3c (see next

note). The only difference is that in 46:3-4 the order of the clauses is reversed since the apodosis

(: ::) precedes the protasis. Indeed, the protasis comprises four clausestwo with beth + in-

finitive ( :: / : c::) and two with sentence-initial yiqtol in v. 4 (lit. let its waters roar let

the mountains tremble).

35

Translation from Keil-Delitzsch, V/3, 72, 75-76 with modifications. Psa 93:3 is one of the main

texts quoted by both Cassuto and Held in order to show the equivalence of the perfect and the imper-

fect forms of the same verbs in parallel lines. However, Cassuto translated as present (the floods lift up

their roaring: The Goddess Anath, 46) while Held translated as past (The floods lifted up, O Lord, the

floods lifted up their voices, the floods lifted up their: The Yqtl-Qtl, 281). In my opinion, the analy-

sis above is not only defendable but also makes better sense in the context of the Psalm. The many wa-

ters of chaos have roared in the past and may roar at their wish in the future; still, God the Almighty sits

enthroned and is in total control of the universe.

36

Lit. Let his breath depart, let he return to his earth, with sentence-initial yiqtol both as prota-

sis and as apodosis (see no. 33 above). Another good example is Psa 91:15-16: (15) When he will call to

21

me, will I answer him (:: :, both volitive forms; lit. Let him call me and I will answer him); / I

will be with him in trouble, / I will rescue him and honor him (:::, both volitive). / (16)

With long life I will satisfy him (:::, volitive x-yiqtol because it is linked to a series of clearly vo-

litive verbal forms) / and show him (, volitive) my salvation.

37

Similar cases are, e.g., Deut 32:11; Psa 18:26-28 // 2 Sam 22:26-28, and Psa 115:5-7.

38

E.g., on the basis of the verbal forms used, Psa 104 comprises three sections: vv. 1-23, 24-30,

and 31-35, and three motives: first, blessing and praise to God, with imperatives, exclamatory phrases, or

jussives; second, Gods epithets, with participles and qatal forms describing Gods works of creation; and

third, purpose of creation, with first-place yiqtol or x-yiqtol, sometimes with lamed + infinitive. Psa 107

also shows an alternating sequence of three motives: praise of the Lord, description of a critical situation

of the people, and cry to the Lord for help.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Summer Stay On Track Grades 2 To 3Dokument68 SeitenSummer Stay On Track Grades 2 To 3Gabe Coron100% (2)

- Basic HebrewDokument6 SeitenBasic HebrewNatalieRivkahAlexander0% (1)

- 1975 - Misreading The Map. 'A Map of Misreading' by Harold BloomDokument6 Seiten1975 - Misreading The Map. 'A Map of Misreading' by Harold BloomMiodrag Mijatovic50% (2)

- Lambdin - Hebrew GrammarDokument503 SeitenLambdin - Hebrew GrammarViktor Ishchenko75% (4)

- The Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewDokument44 SeitenThe Hebrew Noun Presented in English and HebrewjoabeilonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biblical Hebrew Grammar Presentation PDFDokument245 SeitenBiblical Hebrew Grammar Presentation PDFNana Kopriva100% (3)

- Wijnkoop. Manual of Hebrew Syntax. 1897.Dokument234 SeitenWijnkoop. Manual of Hebrew Syntax. 1897.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdDokument330 SeitenSpirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdfcocajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Passive in HebrewDokument11 SeitenPassive in Hebrewovidiudas100% (1)

- Grammatical Remarks: 1. The Hebrew Aleph-BethDokument6 SeitenGrammatical Remarks: 1. The Hebrew Aleph-BethprogramandosumusicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exemplar Song of Hope 1Dokument2 SeitenExemplar Song of Hope 1api-331716140100% (4)

- Hebrew Weak Verb Cheat SheetDokument1 SeiteHebrew Weak Verb Cheat SheetBenjamin GordonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyDokument4 SeitenLearning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyjoabeilonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scripts of India (S. Kalyanaraman, 2014)Dokument51 SeitenScripts of India (S. Kalyanaraman, 2014)kalyanaraman7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Proofs Biblical Hebrew Periodization enDokument11 SeitenProofs Biblical Hebrew Periodization enChirițescu Andrei100% (1)

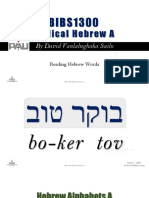

- BIBS1300 02C Reading HebrewDokument35 SeitenBIBS1300 02C Reading HebrewDavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post-Biblical Hebrew Literature: Anthology of Medieval Jewish Texts & WritingsVon EverandPost-Biblical Hebrew Literature: Anthology of Medieval Jewish Texts & WritingsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gelb, Amorite AS21, 1980Dokument673 SeitenGelb, Amorite AS21, 1980Herbert Adam StorckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conybeare - A Grammar of LXX GreekDokument131 SeitenConybeare - A Grammar of LXX GreekmausjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Hebrew MorphologyDokument22 SeitenAncient Hebrew Morphologykamaur82100% (1)

- Gbyrh GBRT - Alison SalvesenDokument11 SeitenGbyrh GBRT - Alison SalvesenTabitha van KrimpenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phonology of Ancient Hebrew - VowelsDokument55 SeitenPhonology of Ancient Hebrew - VowelsPiet Janse van Rensburg100% (1)

- A Is for Abandon: An English to Biblical Hebrew Alphabet BookVon EverandA Is for Abandon: An English to Biblical Hebrew Alphabet BookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verbal Forms in Biblical Hebrew Poetry P PDFDokument352 SeitenVerbal Forms in Biblical Hebrew Poetry P PDFCarlosAVillanueva100% (2)

- A Student's Introduction To Biblical Hebrew: What Are The Essential Features That You Need To Memorize in Chapter 1?Dokument9 SeitenA Student's Introduction To Biblical Hebrew: What Are The Essential Features That You Need To Memorize in Chapter 1?ajakukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masoretic PunctuationDokument26 SeitenMasoretic PunctuationBNoch keine Bewertungen

- Septuagint - Daniel (Chisianus Version)Von EverandSeptuagint - Daniel (Chisianus Version)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Accents in Hebrew BibleDokument17 SeitenAccents in Hebrew BibleInbal ReshefNoch keine Bewertungen

- SteinerDokument45 SeitenSteinererikebenavrahamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Distribution of Object Clitics in Koin e GreekDokument19 SeitenThe Distribution of Object Clitics in Koin e GreekMarlin ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical HebrewDokument25 SeitenPAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical Hebrewivory2011Noch keine Bewertungen

- History of Indic Scripts 2016 PDFDokument15 SeitenHistory of Indic Scripts 2016 PDFclaudia_graziano_3100% (1)

- Targum & Masora: Does Targum Jonathan Follow The Madinhae' Readings of Ketiv-Qere?Dokument20 SeitenTargum & Masora: Does Targum Jonathan Follow The Madinhae' Readings of Ketiv-Qere?AardendappelNoch keine Bewertungen

- PGEG S1 02 (Block 2) PDFDokument87 SeitenPGEG S1 02 (Block 2) PDFआई सी एस इंस्टीट्यूटNoch keine Bewertungen

- J. Philip Hyatt (1967) - Was Yahweh Originally A Creator Deity - Journal of Biblical Literature 86.4, Pp. 369-377Dokument10 SeitenJ. Philip Hyatt (1967) - Was Yahweh Originally A Creator Deity - Journal of Biblical Literature 86.4, Pp. 369-377OLEStarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mishnaic HebrewDokument4 SeitenMishnaic Hebrewdzimmer6Noch keine Bewertungen

- BINS 146 Peters - Hebrew Lexical Semantics and Daily Life in Ancient Israel 2016 PDFDokument246 SeitenBINS 146 Peters - Hebrew Lexical Semantics and Daily Life in Ancient Israel 2016 PDFNovi Testamenti Lector100% (1)

- The Enigma of the Masoretic TextDokument26 SeitenThe Enigma of the Masoretic TextAnonymous mNo2N3100% (1)

- Annette Y Reed 2 Enoch and The TrajectorDokument24 SeitenAnnette Y Reed 2 Enoch and The TrajectorRade NovakovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Rites in Judaism: As Background for Understanding Holy Ghost BaptismVon EverandWater Rites in Judaism: As Background for Understanding Holy Ghost BaptismNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Huehnergard - An Annotated BibliographyDokument21 SeitenJohn Huehnergard - An Annotated BibliographyAntonio Tavanti100% (2)

- A Classification of Conditional Sentences Based On Speech Act Theory - Richard A Young PDFDokument21 SeitenA Classification of Conditional Sentences Based On Speech Act Theory - Richard A Young PDFJoão Nelson C FNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction to BHS Signs and SymbolsDokument6 SeitenIntroduction to BHS Signs and Symbolsbingyamiracle100% (1)

- Guide To The Use of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia - PAUL W. FERRISDokument3 SeitenGuide To The Use of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia - PAUL W. FERRISJohnny HannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studies in Deuteronomy: CJ Oj3Dokument10 SeitenStudies in Deuteronomy: CJ Oj3claudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureDokument272 SeitenNathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureBibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lexical Isoglosses of Archaic HebrewDokument17 SeitenLexical Isoglosses of Archaic HebrewMárcia Souza100% (1)

- Imperial Aramaic Lingua FrancaDokument20 SeitenImperial Aramaic Lingua FrancaTataritos100% (1)

- Origin and Development of Indian Scripts PDFDokument13 SeitenOrigin and Development of Indian Scripts PDFclaudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Morag The Vocalization of Codex Reuchlinianus 1959Dokument22 SeitenMorag The Vocalization of Codex Reuchlinianus 1959adatan100% (2)

- Thesis (Complete)Dokument87 SeitenThesis (Complete)Johnny HannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emannuel Tov. Scribal PracticesDokument325 SeitenEmannuel Tov. Scribal PracticesMark Cooper67% (3)

- The Adverbs For 'Together' in The Hebrew of The Dead Sea ScrollsDokument25 SeitenThe Adverbs For 'Together' in The Hebrew of The Dead Sea ScrollsMudum100% (1)

- (Qimron 1986) The Hebrew of The Dead Sea ScrollsDokument139 Seiten(Qimron 1986) The Hebrew of The Dead Sea ScrollsMudum100% (2)

- Let Actual Test EnglishDokument4 SeitenLet Actual Test EnglishMaria Cecilia Andaya100% (1)

- Summative Test in Creative WritingDokument2 SeitenSummative Test in Creative WritingAnne FrondaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poetics of Architecture - Theory of Design - Anthony C. Antoniades PDFDokument760 SeitenPoetics of Architecture - Theory of Design - Anthony C. Antoniades PDFJessica Santiago100% (7)

- Historical Linguistics 2010Dokument51 SeitenHistorical Linguistics 2010Si vis pacem...Noch keine Bewertungen

- MasoraDokument16 SeitenMasoraSebastian Massena-WeberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parallel Bible Provides Accessible Entry to Original Hebrew TextDokument3 SeitenParallel Bible Provides Accessible Entry to Original Hebrew TextPedroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accents MasoreticDokument16 SeitenAccents MasoreticsikuningNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stanislav Segert, Rendering of Parallelistic Structures in The Targum Neofiti The Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32,1-43)Dokument18 SeitenStanislav Segert, Rendering of Parallelistic Structures in The Targum Neofiti The Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32,1-43)Bibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Four VowelsDokument2 SeitenFour VowelsnativeliteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gottingen LXX Sigla MVPDokument2 SeitenGottingen LXX Sigla MVPGeorge HartinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Militarev - Root Extension and Root Formation in Semitic and AfrasianDokument58 SeitenMilitarev - Root Extension and Root Formation in Semitic and AfrasianAllan BomhardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kaufman Akkadian Influences On Aramaic PDFDokument214 SeitenKaufman Akkadian Influences On Aramaic PDFoloma_jundaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temporal Clause-NiccacciDokument5 SeitenTemporal Clause-NiccacciJosé Estrada Hernández100% (2)

- Biblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualDokument13 SeitenBiblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualcamaziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Israel's Scriptures in Early Christian Writings: The Use of the Old Testament in the NewVon EverandIsrael's Scriptures in Early Christian Writings: The Use of the Old Testament in the NewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Examines Origin of Early Indian ScriptsDokument10 SeitenReview Examines Origin of Early Indian Scriptsclaudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kharo Hī and Brahmi Scripts - Context of Links With Indus Script Hieroglyphs To Catalogue Metalwork, MetalcastingsDokument39 SeitenKharo Hī and Brahmi Scripts - Context of Links With Indus Script Hieroglyphs To Catalogue Metalwork, Metalcastingsclaudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kenoyer2020 Origin Use of Indus ScriptDokument34 SeitenKenoyer2020 Origin Use of Indus Scriptclaudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Table Thesis May 2017Dokument95 SeitenTable Thesis May 2017claudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Get To Know The History BooksDokument28 SeitenGet To Know The History Booksclaudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shemer - Mslib.huji - Ac.il Refer OsDokument26 SeitenShemer - Mslib.huji - Ac.il Refer Osclaudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Get To Know Saint MarkDokument25 SeitenGet To Know Saint Markclaudia_graziano_3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Toward An Oral PoeticsDokument14 SeitenToward An Oral PoeticsTyler SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- William Blake - Selected PoemsDokument21 SeitenWilliam Blake - Selected Poems조수아Noch keine Bewertungen

- Exploring Sensory Imagery and Cultural Significance in Ray Young Bear's "GrandmotherDokument10 SeitenExploring Sensory Imagery and Cultural Significance in Ray Young Bear's "Grandmothersuman dahalNoch keine Bewertungen

- TS Eliot - The Possibility of A Poetic DramaDokument6 SeitenTS Eliot - The Possibility of A Poetic DramaChristopher BournNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Thing of Beauty Poem MCQDokument5 SeitenA Thing of Beauty Poem MCQVivek Agrawal100% (2)

- Tradition and The Individual TalentDokument9 SeitenTradition and The Individual TalentMonikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hum - From The Lover To The Beloved CelebrationDokument14 SeitenHum - From The Lover To The Beloved CelebrationImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- No Dimes For The Dancing Gypsies by Linda King Book PreviewDokument16 SeitenNo Dimes For The Dancing Gypsies by Linda King Book PreviewGeoffrey GatzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 978 3 319 27036 4 PDFDokument421 Seiten978 3 319 27036 4 PDFAndrés Salcedo GüereNoch keine Bewertungen

- How a beach visit leads to loneliness, death and self-discoveryDokument1 SeiteHow a beach visit leads to loneliness, death and self-discoveryestefi paulozzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poem Comparison: My LaDokument3 SeitenPoem Comparison: My LaFaith VNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bloom. Coleridge - The Anxiety of InfluenceDokument7 SeitenBloom. Coleridge - The Anxiety of InfluencemercedesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zindagi Shayari (Top 20 Sher) RekhtaDokument1 SeiteZindagi Shayari (Top 20 Sher) Rekhtarohitkrishnan.connectNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wordplay in Poetry - Assessment Resource - Sample ResponseDokument2 SeitenWordplay in Poetry - Assessment Resource - Sample Responseneindiwe mmasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 3-Two Stories About Flying. Prose 1 - His First Flight Mcqs Based QuestionsDokument25 SeitenCH 3-Two Stories About Flying. Prose 1 - His First Flight Mcqs Based Questionsyoutube addictNoch keine Bewertungen

- HOMER'S ILIAD - Literary Terms and Epic ConventionsDokument2 SeitenHOMER'S ILIAD - Literary Terms and Epic ConventionsNimshim AwungshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- LSAT PT 02 Expl UnlockedDokument44 SeitenLSAT PT 02 Expl Unlockedrohit patnaikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preparing For The SOL EOC English Test Reading Literature and ResearchDokument254 SeitenPreparing For The SOL EOC English Test Reading Literature and ResearchJana Pavlovicova Lehocka0% (1)

- Syllabus On LiteratureDokument8 SeitenSyllabus On LiteraturedeariecreamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nature & Art in Keats' Ode & To AutumnDokument4 SeitenNature & Art in Keats' Ode & To AutumnLauriceWongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle: Aristotle's Poetics SummaryDokument3 SeitenAristotle: Aristotle's Poetics SummaryRohit S NairNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Snake Trying Lesson Plan 1Dokument5 SeitenThe Snake Trying Lesson Plan 1megha raj100% (3)

- Rhytmic Structure in Iranian Music Vol2Dokument164 SeitenRhytmic Structure in Iranian Music Vol2Prokop FialkaNoch keine Bewertungen