Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chapter 55

Hochgeladen von

Muhammad FarhanOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chapter 55

Hochgeladen von

Muhammad FarhanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

KASHMIR: BUILDING PEACE THROUGH TRADE

Ejaz Mir, a young entrepreneur, lives in a small town at the border of Kashmir, which is divided into an Indian and a Pakistani side. Whenever the tensions between both nuclear powers escalate over their borders, shadows of war and clouds of fear hover over this town. Since childhood, this young trader has been witnessing shells falling, wounded civilians and the destruction of hospitals, schools and business structures in his surrounding area. However, when in 2002 India and Pakistan decided to establish travel and business links between the two divided parts of Kashmir, after 60 years of lack of communication, he finally regained hopes of rebuilding his stagnant business. Barter trade The complexity of these business procedures generates several difficulties for traders. Mirs small firm deals with importing and exporting goods between the Indian and Pakistani regions of Kashmir through trans-border trade. Today, this young entrepreneur deals with a peculiar business method. He sends and receives goods across the border, but no money is involved. The entire business procedure depends on bartering. The complexity of these business procedures generates several difficulties for traders. India and Pakistan have allowed Kashmiri

traders to merchandise only 21 items through the trans-border trading system. They have approved a list of tradable commodities like vegetables, spices, locally-made handicrafts and so on. Traders say that the governments of India and Pakistan can revoke any commodity from the approved list of products and goods, even if these items have already been transported to the other side of the border. This engenders waste as the material is abandoned, and its owners therefore suffer from important financial losses. Financial disputes Traders accuse Pakistani officials of regularly seizing their loaded trucks, thus violating national trade laws. They allow us to carry out the trade when we pay them kickbacks, but now they have seized our trade goods worth millions of Rupees complains Ejaz Mir. Traders have nevertheless shown their willingness to pay any legal tariffs if necessary. We can pay the government if it introduces any mechanism for the collection of tax, says Sheikh Walid Rasool, a trader. Intra-Kashmir trade is one of the confidence-building

measures (CBM) that resulted from the 2004 peace agreement between

India and Pakistan, which both control the Himalayan state of Jammu and Kashmir. Traders consider this trade free from any tax or duty which India and Pakistan levy on their international borders. Pakistani trading authorities say that Cross Line of Control (LoC) Trade aims at encouraging trade between the Kashmiri businessmen of Pakistan and India. Therefore, goods of Indian provenance imported through the Cross LoC Trade, must be consumed within the non-tariff area of Pakistani Kashmir and cannot be sold and consumed in the tariff areas of Pakistan. Communication and logistic barriers Besides suffering from complex financial and administrative

troubles, traders from both countries also face some outrageous communication restrictions in their business dealings. There is a ban on international direct dialling in Kashmir, which impedes traders to talk with their counterparts freely. There are a few hotlines installed in the Trade Facilitation Centre (TFC), but traders phone conversations are monitored by government functionaries, who describe it as essential for security purposes. The lack of free communication causes major strategic business problems and disputes. Sometimes, these traders suffer from payments default by their counterparts. Sateesh Kumar, who is based in Srinagar, a city in the

Indian-administrated part of Kashmir, abandoned his business a year ago when his Pakistani counterpart failed to make his payments: I cant chase my defaulter because we dont have any means for that and there is therefore no possibility of resolving the issue. I would not have to face this situation if they provided us with the possibility to do business through bank or cash payments In this barter system, traders have no guarantee of equal return and recovery of differential amounts from their counterparts across the LoC. Indeed, some Pakistani traders also complain about similar problems of payment failure. Officials admit that the complex payment system involved in these trading procedures is creating discrepancies amongst the business community. Neither India nor Pakistans governments have any control over the payment processes, therefore, when these divergences arise, neither of them takes the responsibility to resolve these issues, and this should change, believes Brigadier (r) Ismail, head of the Travel and Trade Authority. He supported the traders demand of increasing the trade list and the number of trucks to carry commodities. Currently, the Indian government allows only 25 vehicles from the Taitrinote-Chakan-Da-Bagh crossing point and 50 from Chakothi, Amman (Peace) Bridge. The Indian region of Kashmir has a bigger

market and a more important consumption of goods than the Pakistani part, hence traders demand an increase in the number of vehicles from the Pakistani side. New developments Trade relations between New Delhi and Islamabad have recently gone through remarkable transformations. Besides trade exhibitions, business-to-business networking and other joint ventures, both governments are considering the possibility of opening bank branches in each others countries to utilize mutual human and financial resources. However, distrust and fear still prevail when considering geostrategic affairs like Kashmir or information-sharing about nuclear weapons. As a result, India rejected the Pakistani proposal of moving artillery greater than 130 millimetres at least 30 kilometres away from the Line of Control. Indeed, India is still cautious about the alleged infiltration of Pakistani-sponsored militants into Indian-administered Kashmir. Both countries accuse each other of having violated the cease fire that they agreed to in 2003. Militancy erupted in Indian-administered Kashmir in 1989. India blames Pakistan for fuelling Kashmirs unrest and sponsoring insurgency in the region. Islamabad denies this and considers Jammu and Kashmir a disputed territory. The benefits of the Kashmir trading scheme

Trans-LoC trade has contributed to the improvement of social, economic and human ties In 2011 goods dominated over guns across the Line of Control in Kashmir.The Indian Parliament, which received a deadly attack by militants in 2001, was informed by Defence Minister A K Antony that 68 militants attempted to infiltrate through the Line of Control (LoC) in September and October 2011, as compared to 85 such attempts during the corresponding period in 2010. On the other hand, the volume of trans-LoC trade increased surprisingly during this period. According to officials from Indian Kashmir, about 8000 trucks crossed over the LoC and 7000 trucks came from the Pakistani side of Kashmir in 2011, compared to 3798 trucks driving down the LoC from the Chakothi border in 2010. The trans-LoC trade has contributed to the improvement of social, economic and human ties between the divided regions of Kashmir, and has also strengthened Indo-Pak trade realisation. It is cultivating seeds of harmony, trust and mutual respect between Pakistani and Indian traders, maintains Mr. Pawan Anand , President of the Traders Association in Jammu and Kashmir. Cross LoC trade has changed the socio-economic status of many people. And we believe it will bring more optimistic transformations in the future.

Trade has indeed left some positive and hopeful imprints upon the conflict-ridden society of Kashmir, where it is fostering mutual trust and sustainable peace International peace has been recognized over the years as an essential condition for the enjoyment of human rights and justice for all. It is axiomatic that international peace defines the basic condition for the respect for civil and political rights and promotion of economic, social and cultural rights. In an environment of turmoil and tribulations, the very concept of human rights becomes a mockery. The most promising way to prevent conflict is to eliminate its causes. The latter are well known. Violence and mayhem ensue because of mankinds desire for domination, wealth, territory and destruction of people and things that are disliked for religious, racial, ethnic, cultural or other reasons. After an end to the ideological confrontation between East and West, the international community had reason to hope that hostilities in many parts of the world would also come to an end and the residual regional conflicts would be resolved peacefully through negotiations. However, contrary to our expectations, in many parts of the world, bloody conflicts are raging which have destroyed all the hopes for a humane and stable world order. The unresolved conflicts of Palestine and Kashmir are a challenge to international leadership and the human conscience

Although the UN has written declarations that affirm the rights of vulnerable populations, there must be a greater worldwide effort on the part of governments, NGOs, businesses, and UN agencies to incorporate peace, justice and human dignity into internationalization and globalization. Peace, justice and human dignity cannot take a back seat as societies globalize their trade, supply chaining, and outsourcing. Freedom and justice must prevail above all political and economic aspects of international trade relations, and treaties even if it requires canceling trade agreements with countries that blatantly allow gross human rights violations to continue. It is the responsibility of everyone operating in the international arena to ensure that peace, justice and human dignity are protected. Global ethics must be fully integrated into the process of globalization. As long as any one human being suffers the indignation of rape, slavery, torture or sexual exploitation, then peace, justice and human dignity remain absent from the human race as a whole. The South Asian region furnishes an undeniable evidence of how respect for human rights cannot be achieved without first creating conditions for international peace. The people of Kashmir were pledged by no less authority than the UN Security Council to exercise their right to decide their future under conditions free from coercion and intimidation. The denial of this right is directly inter-related with the peace of the region.

I believe that peace and justice in Kashmir are achievable if all parties concerned India, Pakistan and Kashmiris make some sacrifices. Each party will have to modify its position so that common ground is found. It will be impossible to find a solution of Kashmir conflict that respects all the sensitivities of Indian authorities, values all the sentiments of Pakistan, keeps intact the unity of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, and safeguards the rights and interests of the people of all the different zones of the state. Yet this does not mean that we cannot find an imaginative solution. It is possible provided all parties will modify their stated positions and show some flexibility. I also believe that peace and justice in Kashmir are achievable only if pragmatic and realistic strategy is established to help set a stage to put the Kashmir issue on the road to a just and durable settlement. Since, we are concerned with setting a stage for settlement rather than the shape the settlement will take, I believe it is both untimely and harmful to indulge in, or encourage, controversies about the most desirable solution. Any attempt to do so amounts to playing into the hands of those who would prefer to maintain a status quo that is unacceptable to the people of Kashmir and also a continuing threat to peace in South Asia. We deprecate raising of quasi-legal or pseudo-legal questions during the preparatory phase about the final settlement. It only serves to befog the issue and to convey the wrong impression that the dispute is too complex to be resolved and that India and Pakistan hold equally

inflexible positions. Such an impression does great injury to the cause. We anticipate that this forum will make valuable contribution not only to build peace in the pursuit of justice, but also to build stronger partnership between members of various religious groups and civil society for this important task. Source: by courtesy & 2009 Ghulam Nab

Nuclear doctrine, declaratory policy, and escalation control During the 10-month long Indian and Pakistani military mobilization of 2001-02, one of the earliest casualties was the official channel of communication between the two states. With New Delhi deliberately downgrading its relations with Islamabad by withdrawing Indias High Commissioner to Pakistan, and eventually his Pakistani counterpart in India, and halving the strength of respective diplomatic missions diplomatic communications were fatally disrupted. This increased the dependence of both states on public diplomacy and rhetoric as the most significant channel of bilateral communication. Such a state of affairs, with inherent possibilities of misperceptions and miscalculations, had dangerous implications for two nuclear-armed states. During much of the border confrontation, India and Pakistan were communicating with each other on a public basis in terms of conveying stated intentions, as well as assessing respective intent and capabilities. By their public statements or deafening silences, by the issue of provocative and inflammatory statements and subsequent denials or clarifications, or by relative action, or even inaction on various issues, both countries attempted to send signals on nuclear as well as conventional matters. These signals were multiple in nature, carried out at multiple levels, and addressed to multiple constituencies internal, regional, and international. For both India and Pakistan, the most important constituencies were the domestic public, each other, and the U.S., which had the most influence in the region. For Delhi, the U.S. could help pressurise Pakistan to cease cross-border infiltration of militants into Indian-administered Kashmir; for Islamabad, the U.S. could restrain Delhi from military action. Although India attempted to convey clear messages, its nuclear signals appeared confusing, and, at times, were at cross-purposes with one

another. It is also not clear whether these signals were even perceived as intended by Pakistan or the other parties. If they were, it is not clear whether they were fully understood, or even taken cognisance of, especially by Pakistan. In this context, this paper examines the challenges and complexities of Indias nuclear signalling during the 2001-02 Indo-Pakistani border confrontation. Disruption of Diplomatic Communications Soon after the terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament on December 13, 2001, New Delhi began attempting to coerce Islamabad into complying with its demands, and ending cross-border terrorism in Jammu & Kashmir, and other parts of India. On December 14, New Delhi issued a verbal demarche to Pakistan seeking action against the activities of two Pakistan-based terrorist organizations Jaish e Mohammed (JeM) and Lashkar e Toiba (LeT) identified by Indian intelligence agencies as being responsible for the attack on Parliament. This was followed by another demarche on December 31 seeking the return of 20 fugitives wanted by New Delhi, believed to be living in Pakistan. As part of its coercive diplomacy against Pakistan, India launched Operation Parakram (valour) on December 19, which was to constitute the largest and longest mobilisation of the Indian armed forces. This was a deliberate move, taking place amidst the global war on terror, to threaten the use of force against Pakistan. It included the deployment of Indias three strike corps (comprising armoured and mechanised formations) at forward positions on the international border with Pakistan. All leave to armed forces personnel was restricted, and all training programmes and military courses suspended. With Pakistans counter-mobilisation, nearly one million armed personnel were deployed across the India-Pakistan borders.

In order to further increase pressure on Islamabad, New Delhi systematically began to downgrade its diplomatic relations with Pakistan, along with the ending of all transportation linkages and economic relations. On December 14, the day after the attack on Parliament, New Delhi sought the immediate recall of its High Commissioner in Islamabad, Vijay Nambiar, along with the termination of all bus and train services between the two countries, to be effective from January 1, 2002. While it was widely expected that Pakistan would reciprocate by recalling its High Commissioner in New Delhi, Ashraf Jehangir Qazi, it did not do so. In an astute move, Qazi remained High Commissioner to India for the next four months, even though he was deliberately ignored by the Indian Government during this period. In continuation of its policy of coercive diplomacy, on December 21, 2001, India ordered the reduction of the strength of the Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi by half within 48 hours, and restricted the movement of Pakistani diplomats in New Delhi. It also banned all overflight of Indian territory by Pakistani aircraft from January 1, 2002. Within an hour, Pakistan announced reciprocal diplomatic measures, including the reduction of the strength of the Indian High Commission in Pakistan, and restrictions on the movement of Indian diplomats in Islamabad. On May 18, 2002, Pakistani High Commissioner Qazi was finally asked to leave India, in the wake of the terrorist attack in Kaluchak, near Jammu city. The Indian Government told Pakistan to recall Qazi within a week, for sake of parity.1

By early January 2002, both the Indian and Pakistani High Commissions in respective capital cities were operating on a skeletal staff, the Indian Mission in Islamabad did not have a resident High Commissioner, and all transportation links between the two countries were cut off, amidst

the growing military mobilisation of armed forces personnel (to reach a figure of 1 million) across the Indo-Pak borders. Although Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee and Pakistani President Musharraf met twice during the border confrontation at multilateral summits in third countries the seven-nation South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Summit in Kathmandu in January 6-7, 2002, and the 16-nation Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures (CICA) at Almaty, Kazakhstan, on June 3-4, tensions did not ease. Indeed, according to the Indian National Security Advisor, Brajesh Mishra, the five minute Vajpayee-Musharraf meeting in Kathmandu was merely a replay of the Agra Summit (2001) (where Vajpayee and Musharraf failed to agree on the core issues of tension between the two states).2 Nuclear Signalling Past and Present In view of these developments, it was not surprising that nuclear signalling by both New Delhi and Islamabad was unprecedented in terms of the duration as well as the variety and multiple levels at which the signals emanated. The ten-month border confrontation (December 2001 October 2002) was the longest period of military mobilisation by both countries since their independence in 1947. A variety of nuclear signals took place flight tests of ballistic missiles, public speeches - to the public and the armed forces - and press briefings. These also emanated at multiple levels in both countries the political, military, and bureaucratic leadership. During the Kargil conflict of MayJuly 1999, nuclear signalling by Islamabad was restrained. This appears to have been due to Indian military action limited to its own side of the Line of Control (the de facto border dividing Indian - and Pakistani administered Kashmir), along with the Indian political leadership signalled restraint in the use of force across the LoC. The official Indian

post-conflict review - the Kargil Review Committee Report of December 15, 1999 reveals that Pakistan conveyed only veiled nuclear signals to India during the conflict. However, in May 2002, a former senior Clinton administration official publicly alleged that Pakistan was preparing its nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles for possible deployment in July 1999.3 Since New Delhi may not have been aware of such a move, and taking place as it did towards the end of the conflict, it did not impact upon the situation on the ground. Prior to the nuclear tests of 1998, there were two instances of nuclear signalling - during the spring 1990 Indo-Pakistani military crisis and Indias military Exercise Brasstacks in 1987. In 1990, Pakistan is believed to have made an implied nuclear threat to India, although Robert Gates, the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), did not make any reference to this nuclear signal during his mission to India in May 1990. During Exercise Brasstacks Pakistan conveyed two nuclear signals to India through diplomatic channels to Indias High Commissioner in Islamabad, S.K. Singh, and publicly by Dr. Abdul Qadir Khan, its chief nuclear scientist, in an interview published after the end of the military exercise in the British Observer newspaper. In an attempt to understand Indias nuclear signals during the 2001-02 border confrontation both in terms of conveying stated intentions, as well as assessing respective intent and capabilities it is best to examine them in three phases, with the first two comprising the crises periods, and the third the non-crisis period. The first phase can be defined as the period between the terrorist attack on Parliament on December 13, 2001 and the attack on the Army residential camp in Kaluchak on May 14, 2002; the second phase covers the post-Kaluchak period till the end of the crisis in mid-June, 2002; and the final phase from Indian Prime

Minister Vajpayees claim of victory without war on June 17, 2002 to his hand of friendship speech in Srinagar on April 18, 2003. Nuclear Signalling - Phase I: December 13, 2001 May 14, 2002 These five months included the first crisis in the immediate aftermath of the December 13 attack, when, according to the Indian National Security Advisor, Brajesh Mishra, New Delhi came close to using force against Pakistan.4 This period comprised half the total duration of border confrontation and military mobilisation between India and Pakistan. During this period, New Delhi appeared keen to give two major signals to its multiple constituencies its domestic public, the Pakistani Government, and Washington, D.C. although it did not always appear as such. First, that its much-publicised threat to use conventional force against Pakistan was real and credible, with limits to its restraint and patience fast-approaching unless, of course, Pakistan complied with its demands to end cross-border terrorism. Second, that it would strenuously avoid any nuclear signalling to Islamabad, as well as deliberately ignore any nuclear signalling from Islamabad, over the use of Pakistani nuclear weapons to deter an Indian conventional military attack. New Delhi was only too aware that since the early 1990s Pakistan had been attempting to link the Kashmir dispute to nuclear weapons in a political manner. It was not felt that this crisis would be any different. By showing Kashmir as a nuclear flashpoint, Pakistan hoped to involve the international community in its resolution, which was largely opposed by India (with the exception of U.S. involvement in facilitating the deal with Pakistan to formally end the Kargil war). Any Pakistani nuclear signalling during the confrontation was therefore to be seen by New Delhi as a political ploy to raise international concern over a nuclear war over Kashmir.

It was not surprising, therefore, that in the first official reaction to the December 13 terrorist attack, the Indian Cabinet vowed to liquidate the terrorists and their sponsors wherever they are, whoever they are, but without naming any state. Prime Minister Vajpayee also boldly stated, now the fight against terrorism has reached its last phase. We will fight a decisive battle to the end, without going into specifics. However, within two weeks of these events, New Delhi and Islamabad were exchanging navigational coordinates of their nuclear installations and facilities on January 1, 2002, as they had done for the past thirteen years, in accordance with the bilateral agreement on the Prohibition of Attack against Nuclear Installations and Facilities (December 31, 1988). Neither Delhi nor Islamabad apparently felt it prudent to discontinue existing practice on this Confidence Building Measure (CBM), notwithstanding tense bilateral relations. Both apparently felt that continued notification was an easier option than refusing to do so unilaterally. Especially, as the agreement had no security implication of any significance, with both states deliberately continuing to neglect to notify each other of one nuclear-related facility each, without any consequence. However, this may have sent mixed signals to each other of reassurance that nuclear-related CBMs were insulated from the upheavals of politics, although this may not actually have been the case. The announcement that Musharraf was preparing a televised address to the nation on January 12, 2002 was met with a sense of expectation in New Delhi for two reasons firstly, that Indias politico-military pressure could have begun to work, and secondly, that this could be reflected in Musharrafs speech, with Pakistan preparing to meet some of Indias demands. Dressed in civilian clothing, and apparently reading from a handwritten text, Musharrafs speech attempted to cater to a

multiple audience. Although New Delhi cautiously welcomed Musharrafs announcements (including the ban on five sectarian and jehadi organisations) as a major shift in Islamabads policy, it was well aware that it fell short of the goals envisioned in its coercive diplomacy policy. In essence, Musharrafs promises needed to be implemented by concrete action on the ground. The first nuclear signal from Islamabad emanated from Pakistani President Musharrafs speech on the occasion of Pakistans National Day on March 23, 2002. Not only was his speech seen in New Delhi as a reversal of his January 12 promises, but it was tinged with a warning to India of an unforgettable lesson if it dared to challenge Pakistan. The unforgettable lesson was seen as alluding to the use of Pakistani nuclear weapons to counter an Indian conventional attack across the LoC. Although there was no official response to this nuclear signal by the Indian Cabinet, Defence Minister George Fernandes criticised Musharrafs statement as childish. Surprisingly, the second nuclear signal from Islamabad came at a time of relative calm along the Indo-Pakistani borders. On April 6, 2003 the well known German weekly newsmagazine, Der Spiegel, published an interview with Musharraf, quoting him as saying that in the event that pressure on Pakistan became too great, as a last resort, the atom bomb is also possible. The sensational title of the interview, Kaschmir konflikt: Pakistans Musharraf droht Indien mit der Atombombe (Kashmir Conflict: Musharraf of Pakistan threatens India with Nuclear Bomb) added to its impact. The translation of Musharrafs statement reads as follows, "Using nuclear weapons would only be a last resort for us. We are negotiating responsibly. And I am optimistic and confident that we can defend ourselves using conventional weapons... only if there is a threat of Pakistan being wiped off the map, then the pressure from

my countrymen to use this option would be too great". 5 Amidst much sensational international press coverage the following day, the spokesman of the Pakistani Government clarified that Musharraf had actually said that the use of nuclear weapons is only as a last resort, if all of Pakistan were threatened to disappear from the map.

Significantly, Prime Minister Vajpayee publicly declined to comment on Musharrafs interview, stating, I will not like to comment till I see the entire statement. Not surprisingly, Vajpayee never did respond to the Der Spiegel interview. During this phase, the only exceptions to New Delhis policy of avoiding all nuclear signalling, took place, perhaps inadvertently, with Indian Chief of Army Staff (COAS) General Padmanabhans press conference on January 11, 2002, and the flight-test of the Agni 1 ballistic missile on January 25, 2002. The day prior to Musharrafs much advertised address to the nation, General Padmanabhan called a press conference, ostensibly to brief the media on the high state of armed forces preparedness on the borders. At the press conference, he pointed out that the possibility of a nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan was in the realm of the unknown, and India had already declared that it would not be the first to use nuclear weapons. However, in response to a query from a journalist, Padmanabhan gave an unclear warning to Pakistan on nuclear war. He stated that India possessed the capability of a retaliatory strike, and, warned that if any country was mad enough'' to initiate a nuclear strike against India, then the perpetrator of that particular outrage shall be punished severely.6

While this was clearly contradictory to Indias unstated policy on nuclear signalling, what was equally interesting was the response to this statement from the Ministry of Defence (MoD). Within hours, in an unprecedented manner, Defence Minister George Fernandes, publicly repudiated the uncalled for concerns caused by the army Chiefs observations, much to the consternation of his troops. In a written statement, Fernandes pointed out that nuclear issues should not be handled in a cavalier manner.7 However, within two weeks of George Fernandes statement, India flight-tested its medium-range Agni ballistic missile on January 25, 2002, on the eve of its Republic Day. Although Pakistan was provided advanced notification of the missile test (along with the P-5 states), in the spirit of the Lahore Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) (February 21, 1999), it was clear that a nuclear-capable ballistic missile with special characteristics had been tested. Notwithstanding the statement of the official spokesperson of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) that "this (test) is not directed against any country", considerable publicity was given to the range of the missile - 700 kms with the implicit signal that it was, quite clearly, a Pakistan-specific nuclear-capable missile. Nuclear Signalling - Phase II: May 14, 2002 June 17, 2002 This one-month was the tensest of the entire military confrontation, when New Delhi came close to using force against Pakistan for the second time, after the May 14 terrorist attack in Kaluchak. During this period, the war rhetoric from India was at an all-time high, with New Delhi appearing hard-pressed to continue threatening the use of force, whilst deliberately ignoring Pakistans nuclear signalling, which came fast and furious. An added dimension to Indias policy appeared to be a

public appeal to the international community to reign in Pakistans support of terrorism. Just after the Kaluchak attack, Vajpayee informed President George W. Bush in a telephone call that, India will take appropriate action. Vajpayee also informed Parliament that the nation would counter the attack at Kaluchak. Subsequently, both Houses of Parliament adopted a unanimous resolution condemning the most dastardly attack, and pledged to end the senseless acts of terrorism. The Indian COAS, General Padmanabhan, on an official visit to Nepal, was quoted as stating, the time for action has come, though he added that this was a political decision. On May 20, Union Home Minister L.K. Advani said the Government would go ahead and win the proxy war like we did in 1971. However, on May 21 in Jammu, Vajpayee stated that he did not see any war clouds. In Kupwara, the following day, addressing Army personnel, he contradicted his earlier statement by emphatically asserting that the time has come for a decisive battle and we will have a sure victory in this battle. In Srinagar the next day, questioned on his statement on war clouds, Vajpayee stated that the sky may be clear, but sometimes even when the sky is clear there is lightning, but he hoped that lightning would not strike. In a formal statement issued on the occasion, Vajpayee was quoted as having stated that India was preparing for a decisive victory. These statements were perceived by Indian security analysts as referring to a possible surprise attack against Pakistan. A war of words also appeared to be playing out on the Indian media. To an unsourced Indian media report that Pakistan had deployed nuclear-capable Shaheen-1 ballistic missiles (with a range of 800 kms) on the border, an unnamed Indian official was quoted as stating that Indias missile systems had been in position for some time.

These were, arguably, the most important though confusing and apparently contradictory - Indian pronouncements at a critical juncture of the crisis. It is crucial to note that Vajpayees comments on a decisive battle on May 22 were made during an address to Army troops in Kupwara. These were officers and jawans who were already beginning to tire of being at the highest level of operational preparedness for over five months, amidst harsh weather conditions. Vajpayees speech essentially appeared intended to boost the morale of Indian armed forces personnel, and provide some direction to the increasing confusion over the future course of action vis--vis Pakistan. But, at the same time, it appeared intended to impact on Islamabad and Washington, especially the latter in indicating limits on Indias patience over Pakistans perceived intransigence. This was reflected a few days later as well. On May 26, a day before Musharrafs well-publicised second address to the nation, Vajpayee gave a stern warning to Pakistan, while, at the same time, stressing the critical role the international community could play in reigning in Pakistan, and averting a war. From the northern hill station of Manali, where he had ostensibly gone on holiday after his visit to Jammu & Kashmir, Vajpayee reflected that we should have given a fitting reply the day they attacked Parliament. Although this was subsequently clarified, as not stating that we should have struck, but that it would have been better tohave taken action immediately after December 13, its import was clear.7 At the same time, Vajpayee added, world leaders told India to keep patience while condemning the December 13 attack. But, India wont follow the same advice now. The world should understand there is a limit to Indias patience.

Musharrafs televised address to the nation on May 27 was seen as another opportunity to ease tensions with India, the first having been frittered with the lack of implementation post-January 12. But, dressed in military uniform, Musharrafs speech was perceived as highly provocative in New Delhi. Not surprisingly, the Indian Governments response was harsh and focused. At a press conference the following day, External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh began by stressing that the address was both disappointing and dangerous; disappointing in the repetition of earlier assurances, and dangerous, as tension has been added to, not reduced. Partly in response to the war rhetoric emanating from New Delhi, a senior member of the Pakistani Cabinet, Lt. General Javed Ashraf Qazi, told the official Iranian News Agency (IRNA) in Islamabad on May 22 that Pakistan would not hesitate to use nuclear weapons if its survival was at stake. As Minister for Railways, and a former Chief of the ISI (1993-95), Qazi stated, "If it ever comes to the annihilation of Pakistan then what is this damned nuclear option for, we will use (it) against the enemy," He added, "if Indians will destroy most of us, we too will annihilate parts of the adversary. If Pakistan is being destroyed through conventional means, we will destroy them by using the nuclear option as they say if I am going down the ditch, I will also take my enemy with me. A week later, Pakistans Permanent Representative to the UN in New York, Munir Akram, asserted his countrys right to use nuclear weapons against Indias conventional superiority. At a press conference in New York on May 29, his second day in office, Akram stated, "we have to rely on our own means to deter Indian aggression. We have that means and we will not neutralise it by any doctrine of no first-use". Accusing India of having a license to kill with conventional weapons, he queried

how can Pakistan, a weaker power, be expected to rule out all means of deterrence? Although none of these Pakistani statements were ever denied, or alleged to have been, misquoted by the media, additional pronouncements were made to alleviate their impact, in view of possible negative international public opinion. In an interview to the Washington Post published on May 26, Musharraf attempted to downplay the threat of nuclear war. On being asked to describe the circumstances in which he would consider using nuclear weapons if war were to erupt, he said, This is a it is such a question which I wouldn't like to even imagine, frankly, that we come to a stage where this is due. But let me give an assessment that this stage will never comeWe have forces. They follow a strategy of deterrence. And we are very capable of deterring them I really don't think we will ever reach that stage, and I only hope that we I hope and pray that we will never reach that stage. It's too unthinkable. Nonetheless, in the midst of this rhetoric, Pakistan flight-tested three types of nuclear-capable ballistic missiles. Although Islamabad also unilaterally provided New Delhi (along with the P-5 and other neighbouring states) with advanced notification of these tests in the spirit of the Lahore MoU, their timing could not be missed. On May 25, the North Korean-based Ghauri (Hatf-5) (1,500 km range) mediumrange surface-to-surface ballistic missile was tested, followed by the Chinese Ghaznavi (Hatf-3) (DF-11) short-range (300 km range) the next day. Two days later, coinciding with the visit of British Foreign Secretary, Jack Straw, to Islamabad, Pakistan launched the Abdali short-range (180 kms) ballistic missile. Taking place as they did, amidst the presence of some 5,000 American military personnel in Pakistan, deployed in view of the war on terror in Afghanistan, these tests also

sent

strong

message

of

independence

of

military

action.

Nuclear Signalling - Phase III: June 17, 2002 April 18, 2003 These ten months saw the dramatic easing of Indo-Pakistani tensions through U.S./UK facilitation, the successful conduct of assembly elections in Jammu & Kashmir, and the withdrawal and demobilisation of the Indian and Pakistani armed forces from the international border. This phase ended with Vajpayees famous hand of friendship speech in Srinagar. During this non-crisis period, Indias policy on nuclear signalling was abruptly reversed. Instead of deliberately avoiding and ignoring nuclear signals, as in the recent past, in the current non-crisis phase it appeared intent on conveying to Pakistan the credibility of its nuclear forces and its second strike nuclear capability, in the event of any doubts on this account in Islamabad. Not surprisingly, Indias official nuclear doctrine was also publicised in January 2003. With the dramatic easing of tensions, Vajpayee claimed victory in the crisis in the absence of fighting a war. In an interview to a widely read Hindi language newspaper, Dainik Jagran, on June 17, he was quoted as saying that war with Pakistan was averted only due to Islamabads guarantee that it would crack down on Pakistani-based Islamic militants crossing into Kashmir. This was achieved through international pressure on Pakistan, in order to meet Indias demand that it end cross-border terrorism. In a clear indication that Pakistans nuclear deterrence had not worked, he stated, If Pakistan had not agreed to end infiltration, and America had not conveyed that guarantee to India, then war would not have been averted.10 The MEA was quick to clarify that Vajpayees

remarks should not be construed to indicate that India was ready to start a nuclear conflict with Pakistan.11 Vajpayees remarks were immediately challenged by an indignant Musharraf the following day, when he asserted that deterrence had, in fact, worked. At a dinner for Pakistani nuclear scientists and engineers, Musharraf stated that Pakistans nuclear weapons had brought a strategic balance to South Asia. He said that heightened international concerns of a nuclear conflict in South Asia, and the hesitation, frustration, and inability of India to attack Pakistan, or conduct a socalled limited war, bear ample testimony to the fact that strategic balance exists in South Asia and that Pakistans conventional and nuclear capability together deter aggression.12 India was quick to denounce this statement. While accusing Islamabad of trying to justify its nuclear blackmail, it urged the international community not to ignore the continued manifestations of Pakistani irresponsibility, loose talk, and undiluted hostility towards India, along with the continued concoction of doomsday theories to justify its use of nuclear blackmail.13 In support of his contention, Musharraf, in late December 2002, indicated that he had been prepared to use unconventional weapons in the event of an Indian attack. Addressing veterans of the Pakistani Air Force in Karachi on December 30, he stated that we have defeated our enemy without going into war.14 He stated that the Indian Prime Minister had been informed by visiting world leaders that if the Indian Army moved just a single step beyond the international border or the LoC then Inshallah (By the Will of God) the Pakistan Army and the supporters of Pakistan would surround the Indian Army and that it would not be a conventional war.

Although Musharraf did not specifically mention nuclear weapons in his speech, it was apparent he was referring to little else. Significantly, he also made it clear that Pakistans low nuclear threshold ought to be lowered further, to a single step across the LoC by the Indian armed forces. This was quite different from his earlier (April 6, 2002) last resort nuclear threat. The Indian Government promptly responded by noting these highly dangerous and provocative remarks. Subsequently, there was an official Pakistani attempt to clarify Musharrafs remarks by an attempt at obfuscation, which appeared to serve no real purpose. What Musharraf actually indicated, it was clarified, was the use of only unconventional forces and not nuclear or biological weapons...they (a section of the media) took this unconventional form of people rising against the Indian armed forces as meaning nuclear weapons. These statements prompted Defence Minister George Fernandes into sending a spate of nuclear signals to Pakistan. Fernandes began by saying that he did not take Musharrafs December 30 statement seriously. A week later, he told a Confederation of Indian Industries (CII) gathering in Hyderabad that we can take a bomb or two or morebut when we respond there will be no Pakistan. To a question of the danger posed to India if Pakistani nuclear weapons fell into the hands of hard-line Islamic terrorist elements, he elaborated, in a BBC phone-in radio programme in Hindi on the occasion of Indias Republic day on January 26, 2003, We have been saying all through, that the person who heads Pakistan today has been talking about using dangerous weapons including the nukes. Well, I would reply by saying that if Pakistan has decided that it wants to get itself destroyed and erased from the world map, then it may take this step of madness, but if (it) wants to survive then it would not do so.

Conclusion Amidst the 2001-02 border confrontation, New Delhi attempted to convey different and distinctive signals. During the first phase of the crisis period (December 13, 2001-May 14, 2002), India emphatically threatened the use of conventional force against Pakistan. In the second phase (May 14, 2002 June 17, 2002), an added Indian dimension was the appeal to the international community to reign in Pakistans support of terrorism. During both these crises phases, Indias unstated, but deliberate and circumspect, policy was to avoid any nuclear signalling, while, at the same time, deliberately ignore any nuclear signalling from Islamabad. This was essentially motivated by an over-riding political consideration - to avoid the perception of Kashmir as a nuclear flashpoint by the international community. Indeed, Indias Permanent Representative to the UN in New York, was to describe these events as an artificial nuclear scare. However, during the period of non-crisis (June 17, 2002 April 18, 2003), this policy undertook a dramatic reversal, and emphatically threatened the use of Indian nuclear weapons, and the total destruction of Pakistan, were its (Pakistans) nuclear weapons used first against India. This was essentially aimed at countering Pakistans nuclear signalling during the crisis period, which conveyed Pakistans intent to use nuclear weapons to counter an Indian conventional attack. It appeared to be an attempt to primarily convince Indian domestic public, and Pakistan, of Indias nuclear weapon forces and credibility of its second strike nuclear policy. Nonetheless, these signals were not clear and easily discernible; indeed, the opposite was the norm, with signals from both New Delhi and

Islamabad appearing confusing and ambiguous. Five major lessons emerge from this narrative on Indo-Pakistani nuclear signalling. First. A signal is not always perceived as a signal. It is not always clear that a signal by one side is always seen as a signal by the other. Whereas one side may actually be signalling intent, the other may simply miss it, with worrying implications for stability. Signalling depends, on the first instance, on confirmation of the moves that provide the basis for the signal. But confirmation or rebuttal of the signal requires indications and warning signs that are monitored and conveyed back to the leadership. If these are missed, the signaller may perceive the others absence of action as a response, albeit deliberately low-key, forcing it to raise the stakes in a subsequent signal, and thereby further exacerbating tensions. A case in point was Pakistans alleged movement of nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles for deployment during the Kargil conflict in July 1999, which New Delhi may not have been aware of, and Islamabads consequent reactions, if the conflict had not ended. Second. A non-signal may also be perceived as a signal. It is not always clear when a specific action or an event is perceived as a signal, even though it may not actually have been intended as such. Specific actions may have technological or bureaucratic dynamics independent of on-going political tensions, which could be perceived as signalling. In a charged political environment such assessments would appear to be more the norm than the exception. It is not always the case that specific actions are always well thought out and extensively deliberated within Governments prior to signalling. Third. Signalling is confused by a large number of actors. Although New Delhi perceived signals to its multiple constituencies as fairly clear and unambiguous, they were not perceived as such, due to the number of

principal actors involved. Clearly, the principal signaller was Prime Minister Vajpayee. In addition, Defence Minister George Fernandes, and the External Affairs Ministers - Jaswant Singh, followed by Yashwant Sinha were involved in signalling at various stages of the crises. Interestingly enough, Union Home Minister L.K. Advani was rarely involved in issuing these signals, although he is perceived as hawkish on these matters. But, at critical times, there were also two other major players involved in nuclear signalling Army Chief General Padmanabhan, and Defence Secretary Yogendra Narain. This relatively large number of senior individuals involved in signalling tended to confuse New Delhis signals, as perceived by Islamabad and Washington D.C. Fourth. Signals can be at cross-purposes with one another. At crucial times, New Delhis signals were contradictory to one another. When the Indian Government appeared keen to play down nuclear signals during the crisis periods, the statements by the Army Chief, the Defence Secretary, and the test of the Pakistan-specific nuclear-capable Agni ballistic missile appeared confusing, both to Islamabad and Washington D.C. The subsequent clarifications which ensued, from George Fernandes and the MoD muddied the waters even further. It was not clear, for example, whether the actual signal was the Army Chiefs or the Defence Ministers, especially as they contradicted each other. In a similar manner, it was also not clear whether emphasis ought to be placed on the Defence Secretarys signals or the subsequent rebuttal by the MoD. Finally, it ought to be assumed that Islamabad may have perceived it all as a deliberate series of moves, thereby confusing the issue even further. Fifth. The understanding of signals by both sides was weak. In both New Delhi and Islamabad, it was exceedingly difficult to interpret the others

signals. For example, it was not clear if signals were signals; when signals were not signals; and which actors were sending signals and who were not; exacerbated by signals being at cross-purposes with one another. All this added to greater confusion and made consequent signalling even more difficult.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- ObjectivesDokument10 SeitenObjectivesMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Naveed and ButtDokument5 SeitenNaveed and ButtMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Socio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanDokument3 SeitenSocio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SynopsisDokument10 SeitenSynopsisMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Socio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasDokument3 SeitenSocio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Main Page000Dokument5 SeitenMain Page000Muhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desi Efu ReportDokument66 SeitenDesi Efu ReportMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeDokument2 SeitenRosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muhammad Abdul RaufDokument1 SeiteMuhammad Abdul RaufMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Title Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsDokument4 SeitenTitle Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SahibDokument45 SeitenSahibMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zahid SynopsisDokument10 SeitenZahid SynopsisMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- AsDokument11 SeitenAsMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- To Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Dokument1 SeiteTo Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Muhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityDokument1 SeiteLazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of RamadanDokument4 SeitenImportance of RamadanMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bank of Punjab: Internship Report ONDokument7 SeitenBank of Punjab: Internship Report ONMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanDokument2 SeitenCurriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesDokument4 SeitenChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanDokument2 SeitenCurriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Govt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateDokument1 SeiteGovt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

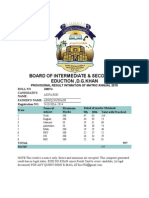

- Board of Intermediate & Secondary Eduction, D.G.KhanDokument1 SeiteBoard of Intermediate & Secondary Eduction, D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- People's Review of ADB, Sindh Rural Development Project DraftDokument46 SeitenPeople's Review of ADB, Sindh Rural Development Project DraftMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesDokument4 SeitenChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muhammad Faisal HanifDokument2 SeitenMuhammad Faisal HanifMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityDokument1 SeiteSajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SaqlainDokument21 SeitenSaqlainMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference Rehmat UllahDokument5 SeitenReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference Rehmat UllahDokument5 SeitenReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference Rehmat UllahDokument5 SeitenReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Bulbul Shah by Yoginder SikandDokument8 SeitenBulbul Shah by Yoginder SikandabirbazazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verification of Genuineness of Educational Certificate Application FormDokument7 SeitenVerification of Genuineness of Educational Certificate Application FormRamu BodduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kashmir Struggle Enters New Phase - 2010Dokument120 SeitenKashmir Struggle Enters New Phase - 2010KashmirSpeaksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ihl and KashmirDokument23 SeitenIhl and Kashmirdarakhshan100% (1)

- July 2, 2013Dokument8 SeitenJuly 2, 2013thestudentageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Places To Visit in IndiaDokument34 SeitenPlaces To Visit in IndiaPramatosh RayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Did You MeanDokument2 SeitenDid You Meananon_231718787Noch keine Bewertungen

- Notice Roll Numberwise Prob 12Dokument10 SeitenNotice Roll Numberwise Prob 12Manasha SaqibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Sacred Groves in Phytodiversity Conservation in Rajouri (J&K)Dokument5 SeitenRole of Sacred Groves in Phytodiversity Conservation in Rajouri (J&K)Ijsrnet EditorialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consolidated CENTRAL UNIVERSITIES ListDokument2 SeitenConsolidated CENTRAL UNIVERSITIES ListTejashri SukareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Late Marriage Among Muslims of Jammu and Kashmir With Special Reference To District Anantnag A Sociological StudyDokument3 SeitenLate Marriage Among Muslims of Jammu and Kashmir With Special Reference To District Anantnag A Sociological StudyIJARP PublicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- AfspaDokument13 SeitenAfspaDarpan MaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Implications of The Revocation of Article 370Dokument3 SeitenLegal Implications of The Revocation of Article 370IJAR JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Detailed Note On The Kashmir Issue Between Pakistan and IndiaDokument3 SeitenA Detailed Note On The Kashmir Issue Between Pakistan and IndiaHadia Ahmed KafeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clsa U Blue Book Oct 2016 PDFDokument32 SeitenClsa U Blue Book Oct 2016 PDFsantanu_1310Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kishor Katti Blog: Real Reason Why Pakistan Is Rattled To The Core Because of Abolishing of Article 370?Dokument35 SeitenKishor Katti Blog: Real Reason Why Pakistan Is Rattled To The Core Because of Abolishing of Article 370?ArnavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daily Paper February 7, 2013Dokument8 SeitenDaily Paper February 7, 2013thestudentageNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 6062168719931474007 PDFDokument8 Seiten5 6062168719931474007 PDFsai kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- KhyberDokument1 SeiteKhyberTaha WaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Party System in Jammu and KashmirDokument3 SeitenParty System in Jammu and KashmirNajeeb HajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Mission in KashmirDokument209 SeitenA Mission in KashmirDn Rath100% (1)

- Management of Pakistan-India Relations: Resolution of DisputesDokument178 SeitenManagement of Pakistan-India Relations: Resolution of DisputesSammar EllahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jammu and KashmirDokument2 SeitenJammu and KashmirSelvaGaneshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walnut Shell - Walnut Shell Manufacturers, Walnut Shell Suppliers & ExportersDokument3 SeitenWalnut Shell - Walnut Shell Manufacturers, Walnut Shell Suppliers & ExportersCicel Jaimani100% (1)

- 10.1007@978 3 030 56481 0Dokument317 Seiten10.1007@978 3 030 56481 0KjellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Notes From Death CellDokument69 SeitenZulfiqar Ali Bhutto Notes From Death CellSani Panhwar100% (10)

- Unemployment and Underemploymentin Rural IndiaDokument9 SeitenUnemployment and Underemploymentin Rural IndiaPranavVohraNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Essay Quotations For Second Year-2Dokument149 SeitenEnglish Essay Quotations For Second Year-2Tayyba Rizwan100% (1)

- Foreign Policy Peace Is Difficult Munir Akramupdated April 14, 2019facebook Count 670 Twitter Share 117Dokument152 SeitenForeign Policy Peace Is Difficult Munir Akramupdated April 14, 2019facebook Count 670 Twitter Share 117Muhammad SaeedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jammu Kashmir Labour Law (1) WordDokument16 SeitenJammu Kashmir Labour Law (1) WordShweta SinghNoch keine Bewertungen