Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

A Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian Children

Hochgeladen von

Samuel Díaz FernándezOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian Children

Hochgeladen von

Samuel Díaz FernándezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian Children

The Impact of the Other in Mitigating Intergenerational Trauma

Samuel Daz-Fernndez

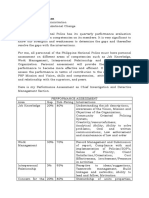

Wheaton College

It is a travesty that children around the world must be subject to the pains of war as if these were a normal component of daily life. It is doubly a crime when a whole nation, as in the case of the Palestinians, is victim to the contained and persistent war battering that has left close to half of its children suffering from the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This estimate does not even take into account the crippling effects that the war has had on the adult population. Sadly, where for most war-torn countries the trauma is one long night of darkness, for the Palestinians the night has not ended since al Nakba in 1948. The main purpose of this essay is to begin to intertwine a psychoanalytic understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder with the socio-political conditions of violence and trauma suffered by Palestinians in the ArabIsraeli conflict. With this in mind, the authors primary intent in the following pages is not to give a definitive account of the conflict or its solution, but rather to lay the groundwork for the project of intertwining by (1) presenting a brief sketch of some of the research conducted to the present concerning PTSD in children (with a special emphasis on Palestinian children), and (2) providing an overarching psychoanalytic framework to explain the nuances of this disorder afresh, especially in regards to the crucial role of the Other in accounting for PTSD development as a result of war trauma in the aforementioned region. In addressing the first task, it will be important to look at the array of studies that have been conducted in the field of post-traumatic stress disorder prevalence in Palestinian children. By and large, these studies show that around half of the Palestinian children sampled who had undergone severe trauma were suffering from full PTSD or PTSD symptomatology. The second task will demonstrate how the onset of post-traumatic stress disorder requires more than basic trauma (as the DSM-IV requires) but a prior neurotic structure similar to what Freud denoted as actual neurosis. This preexisting psychological structure is what leads a person to undergo the somatic effects of post-traumatic stress disorder as the conduit for unmetabolized trauma. In addition, empirical research also shows that trauma, whether it is war, a catastrophe, or a natural disaster, is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder in a person. The final task will consist of tying the two sections together to argue for an existing collective neurotic structure in the Palestinian population that accounts for the marked susceptibility and vulnerability that the children (and adults as referenced in other studies) have of developing post-traumatic stress disorder. Moreover, other contributing factors, such as the lack of discourse, statelessness, displacement, and a lack of a stable national identity will be noted in order to emphasize the way that the unique life conditions of the Palestinian people have turned widespread PTSD prevalence into a chronic intergenerational problem with little hope of healing in the near future. Before going any further there are a few necessary caveats that the author wishes to make to ensure clarity concerning the data used and its subsequent interpretation.1 First, the author has chosen to exclusively focus on Palestinian suffering because, even though both people groups are victims of terrorism and violence and are equally worthy of study and attention, the Palestinian faction has incurred the overwhelming oppression of a powerful and well-armed enemy state. It has also, statistically speaking, suffered more casualties (Burge, 2003). In this way, the author has no intention to be subtle about the large imbalance of atrocities that have been committed against the Palestinian population on part of the Israeli state. This does not in any way undermine the fact that Israelis have also suffered intense trauma as victims of suicide bombings, street violence, and sporadic rocket attacks, which the author hopes will also be examined in other studies. A second question arises prior to the central undertaking: why intertwine psychoanalysis with cultural studies? As Apfel and Simon (2005) state in regards to the role of psychoanalysis in assessing trauma and violence, interweaving is a more apt metaphorthan applied psychoanalysis, as the best work in these areas has

1

Especially given the limited length of the paper, the limited knowledge of the author, and the almost-infinite breadth of data and opinion regarding the subject matter.

represented a form of dialogue and ongoing conversation of analysts and other mental-health professionals with educators, journalists, youth workers, parents, academic social scientists or people in a position to influence policy. It is psychoanalysis interdisciplinary nature that has allowed it to enjoy a unique position in cultural analysis (at least in some circles) and, in this case, in regards to the import of collective trauma and what can be done about it. (Apfel, et al. 2005) In basing its examining power on the past, the psychoanalytic model rightfully lends itself to analyze historical issues of conflict rooted in memory since it assumes that the source of pain is the experiencing of the present through the distorting lens of the past (Silverman, 2004). The great tragedy of the Middle East, however, is that this pain repeats itself, as trauma becomes the mundane, and violent disruptions of ordinary life are part of the quotidian. Thus, these unresolved conflicts of the past, which reside in the competing memories of each group directly involved, result in vicious cycles of physical violence. These then become the visible evidence of coping and defense mechanisms already embedded in the dynamics endemic to the conflict. These solidified mechanisms of operation--what Slavoj Zizek (2008) calls structures of objective violence-- shield the sufferers from having to face the more obscure and meaningful internal conflicts veiled within the collective memory of their respective nation-identities, and from their direct and inextricable connection to a vilified or misunderstood Other. We will soon see how crucial this connection with the Other is. As such, the ad hoc task of intertwining culture theory and psychoanalysis in this case is difficult and controversial, laden with explosive and implicit understandings of the conflict. It is assumed that the hermeneutical lens used must presuppose certain narratives as superior on account of their factual veracity, as well as assume the state of affairs of certain socio-political realities as given, in order to gain any analytical ground. This bilateral conceptual effort must be seen as a cooperative one in which the real fruit of the analytic labor is derived from the supplement of the intertwining fields, particularly when cultural studies lack the real of clinical experience, while the clinic lacks the broader critico-historical perspective (Zizek, 2006). It is in the act of intertwining, then, that the analyst finds her way to the most robust synthesis and interpretation in order to fill the gap where analysts have tended to deal with trauma in individual cases and not attended to larger-scale phenomena (Robinson, 2003). PTSD Research in Palestinian Children A number of recent research findings affirm what has been understood by the general public as the dark predicament of the Palestinian people throughout the last half-century. None have been more injured in this violent imbroglio than Palestinian children. Consequently, even though a war is primarily a physical event with profound physical consequences for those forced to live under it, it is the mental toll on the children that is most remarkable and atrocious. Children living under the effects of political violence and war have been described as growing up to soon and losing their childhood (Boothby, Upton, & Sultan, 2002). It is especially noteworthy to study the effects of trauma on children because childrens response to danger and life-threat include anxiety, somatization, and withdrawal symptoms (Yule, 2002), all fundamental criteria for PTSD diagnosis. In a study by Quota & Odeh (2005), after the Al-Aqsa Intifada on September 28, 2000 through March 31, 2004, it was reported that in the uprising more than 51,288 Palestinians had been injured and 2763 have been killed. Of these, 14,179 who were injured and 701 who were killed were under the age of 18. 12% of these children were left disabled, and most witnessed death and destruction firsthand. Around 50% of children who were injured in the conflict developed post-traumatic stress disorder, contrasted with the normal 34% of mainstream Palestinian school-age children. Quota et al. (2005) observed that in their study on 1000 school-age Palestinian children, of the 547 who had been exposed to traumatic events 63% were diagnosed with PTSD symptomatology (in accordance to the DSM-IV criteria). In another study conducted by Quota in the Gaza strip in 2003 it was found that 33% of the children suffered from acute levels of PTSD, 49% with moderate levels and 16% low levels. In areas closer to Israeli settlements (denoted as hot areas) the rates were even higher. Of the children surveyed, 55% suffered from acute PTSD levels, 35% from moderate levels, and 9% low levels. Moreover, the most prevalent types of trauma exposure for children in community areas is for those who had witnessed funerals, 94.6%; witnessed shooting, 66.9%; saw a friend or a neighbor being injured or killed, 61.6% and were tear gassed, 36.1% (Quota, et al. 2004). These studies demonstrate the heavy toll that children living in Palestine (and especially those living in the zones which receive the brunt of the fighting) live with, so often a toll suffered in the form of post-traumatic stress disorder. The effects of PTSD on the Palestinian population are even more penetrating and dire considering how they expand further than the scope of suffering in the individual person. Inevitably, and particularly because of how central a role the extended family plays in Palestinian culture, the effects of PTSD permeate into the very

infrastructure of society, trickling down ever-more severely onto the children. Seen in this light, Thabet, Tawahina, El Sarraj, and Vostanis (2007) broach the subject of PTSD in the Palestinian experience from a sociological perspective, illuminating the evident link that PTSD has within the life of the middle-eastern family. Thabet et al. (2007) conducted their study in the Gaza Strip, while shells and bullets raged around them, with the intention of establish[ing] the relationship between ongoing war traumatic experiences, PTSD, and anxiety symptoms in children, accounting for their parents equivalent mental health responses. They found that most of the 100 families, with 200 parents and 197 children from the ages of 9-18, reported extremely high numbers of reported traumatic incidents, along with high rates of PTSD and anxiety. A strong association between trauma exposure with total and subscale PTSD scores was also established, especially among the children. Furthermore, and particularly significant in this a strong connection was also made between parental emotional responses and war trauma, and the onset of PTSD and anxiety symptoms in children. The researchers concluded that exposure to war trauma impacts on both parents and childrens mental health, whose emotional responses are inter-related (Thabet, et al., 2007.) They go on to suggest therapeutic interventions that involve families rather than the single individual. Quota and Odeh (2005) emphasize this point in their own study by pointing to the strong familial support and affiliation that exists within Palestinian families, which upon being threatened results in breaking down the very structures of identity, belonging, and security in the life of the Palestinian individual. As shown, although the incidence of PTSD (particularly in political conflict) is directly linked to exposure to violence considerable unexplained variance in casualties symptomatology suggests that additional factors are associated with resilience and vulnerability (Punamaki, Quota & El-Sarraj, 2001). Other research suggests that the following are amongst factors associated with higher risk of developing posttraumatic symptoms: being a part of a minority group (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine), being displaced from your home (Savjak, 2000), the unpredictable nature of trauma suffered (Quota et. al 2003), having suffered torture, lacking a safe home, living currently under traumatic circumstances (Quota et. al 2004), and undergoing multiple exposure to traumatic events (De Jong, Komproe, Ommeren, El Masri, Araya, Khaled, Van de Put, Somasundaram, 2001). Sadly, the Palestinian nation as a whole fulfills the criteria for most of these categories, if not all. This consolidation of research verifies the hypothesis held by many experts that even though trauma (i.e. in the form of violence) is the necessary condition for PTSD, there is a multiplicity of other conditions, which ultimately determine the development and length of this disorder. It also sets the stage to understand other possible necessary conditions for PTSD to evolve within the shared psyche of a people group as in the Palestinian. The Impact of the Other in PTSD as Actual Neurosis A modern understanding of PTSD as outlined in the DSM-IV is one that designates the traumatic experience as the fundamental condition for the subsequent development of the disorder. In this sense the etiology of the disorder seems to be quite clear. In the article Actual Neurosis and PTSD (2005), Verhaeghe and Vanhueule argue that this might not be the case. Their hypothesis is two-fold: firstthat a traumatic incident leads to the development of PTSD if the victim has a pre-existing psychological structure that can be understood as Freuds actual neurosis, and secondly, that this actual neurotic structure is based on early child-taker interactions and that it can be diagnosed as such prior to a trauma or PTSD. (Verhaeghe et al., 2005) Appropriating Lacanian conceptualization in conjunction with modern attachment theory will additionally shed proper light on the formation of this neurotic structure in early development, as yet another necessary condition to the onset of PTSD. According to Paris (2000), a large body of [empirical] research indicates that trauma is a necessary but insufficient condition for the development of PTSD. Considering the fact that most of Western population experiences trauma that fits under the criteria of the DSM-IV, yet only very few actually develop PTSD symptomatology, one can conclude that there is no direct correlation between trauma and the development of PTSD. Though many suffer acute stress disorder in the couple of days following the traumatic event, full-blown PTSD rarely develops. Research also confirms that the importance of the severity of the trauma is relative (possibly insubstantial) in relation to whether PTSD advances or not, surprisingly even in cases of sexual abuse in children (Paris, Andrews, Valentin, 2000). In addition, hereditary studies conducted on twins show that there is a genetic link contributing to the predisposition to the disorder (Kendler, Neale, Kessler, & Heath, 1993; true, Rice, Eisen, & Heath, 1993), yet it is important to remember that the disposition is not specific to PTSD but rather the array of symptoms that it encompasses. Likewise, the intricate interplay between the environment and the persons nature demonstrates that the environment has as big a role to play as the a priori nature of the person does (Paris, 2000).

Studies on the memory functioning of patients with PTSD have also indicated that certain representations of the traumatic event cannot be stored in declarative or narrative memory (functioning via the hippocampus); instead they are initially organized only at the sensorimotor and affective levels, in what is called the implicit, procedural memory (based in the amygdala) (Verhaeghe et al., 2005). This means that it is possible that the traumatic events are associated abnormally, and are thus processed in a somatized way rather than a meaningful way. In turn the representations lack a narrative structure, which must then be constructed post factum in order to achieve any kind of symbolic or meaningful association. In other words, the person will continue to experience the event corporally, but without the explicit remembrance or knowledge of the actual trauma. The question then is: why is the patient suffering from PTSD unable to metabolize the traumatic event in a normal, associative way? According to Verhaeghe and Vanheule (2005), this failure, occurring after the trauma is the core element of PTSD. Freuds notion of actual neurosis shares much in common with the clinical description of PTSD, that will allow us to better understand this failure, and the need for an added fundamental condition for the development of PTSD after trauma, especially as the Freudian concept colludes with Lacanian psychoanalysis and modern attachment theory. Earlier in his career, Freud identified a class of psychoneuroses that he characterized by the absence of a symptomatic superstructure and its associated representational development with regard to sexuality, distinct from those he considered psychoneuroses of defense (Verhaeghe et al. 2005). Those disorders in the former class of actual neuroses (i.e. hypochondria, neurasthenia, and anxiety neurosis) only expressed themselves somatically, were typified by automatic anxiety, and possessed no additional meaning. For this very reason, Freud eventually lost interest in this class because they simply eluded the main task of psychoanalysis, which Freud took to be the drawing out of the unconscious into the conscious realm. Since actual neuroses lacked meaning and only expressed themselves somatically, free association proved to be useless because there was simply nothing to elicit or analyze. Nevertheless, Freud proceeded to hypothesize and describe the actual neurosis as a clinical phenomenon, which we will now compare for congruence with the DSM-IVs description of PTSD. In both of these cases, the central clinical phenomenon is anxiety. Secondly, in both there is a near impossibility of elaborating trauma representationally or meaningfully; instead it is expressed in the compulsive and intrusive reexperiencing of the incident. The traumatic experience is not inscribed within the psychic apparatus and therefore cannot be associatively elaborated (Verhaeghe et. al 2005). In both therefore, the absence of meaning is noteworthy. Thirdly, somatization is a typical characteristic of both PTSD and actual neurosis, indicating the literal embodiment of the trauma. In addition, empirical evidence has actually confirmed an existing neurotic structure in patients diagnosed with PTSD prior to the onset of full PTSD symptomatology. This conclusively determines that the occurrence of PTSD can be related to a preexisting actual neurotic structure, beyond the mere descriptive resemblance of both phenomena. Such a connection was confirmed by a large epidemiological study which showed that more than 60% of patients diagnosed with PTSD had primary disorders preceding traumatic events. The most common, as could be expected, were somatoform disorders (64%), and other specific anxiety disorders, especially social phobia (62%), and simple phobia (71%) (Perkonigg et al., 2000). Thus in accordance with the first hypothesis, PTSD developed in those patients who already had a prior actual-neurotic structure before suffering trauma. The patient consequently developed PTSD since this particular structure prevented the normal, associative way of processing trauma to occur either representationally or meaningfully. Combining Lacanian theory and attachment theory with Freuds notion of actual neurosis, Verhaeghe and Vaneheule, move on to posit the importance of the role of the Other in mitigating trauma, which in effect prevents PTSD from developing. This point will be primarily developed from a summary understanding of the Other in Lacanian theory, sidestepping attachment theory (even while understanding its importance in a more nuanced account). The Others role is axiomatic to the development of subject formation as it grounds the primary mirroring act of the child since birth (considering the child has no identity at birth), also providing a visual and textual model for arousal regulation and identity formation. The child literally receives images and words for its internal state from the Other. (Verhaeghe, 2005) The subject thus comes to know himself by identifying with the Other, primarily by the way that the Other acts in general and in response to the presence of the subject. The subjects identity is thus forged through its direct interaction with the Othera never-ending process of subject formation by continuously identifying with the very given signifiers of discourse itself. The Other, then, in the form of both concrete Other --father and mother--and language itself, forges the identity of the subject in such a way that its absence or presence equally influences whether PTSD does or does not subsequently evolve after trauma is experienced. When the Other has failed to fulfill its essential function of mirroring and representing the subject, especially in relation to regulating the drives, the subject cannot develop a psychical apparatus to handle arousal in a

psychical way. Moreover, the subject fails to achieve a proper synthesis of major ego functioning and identity formation, and therefore develops a recurring inability to process the external symbolic order. The inability disallows the proper association of the traumatic incident in meaningful memory. This then forms the basis for a preexisting neurotic structure, causing the trauma to be experienced somatically in the absence of the Other. Whereas the Other provided the subject with coordinates for the possibility of proper processing, the lack of one impedes such the necessary process. Predictably, somatization occurs alongside a combination of automatic or traumatic anxiety, and separation anxiety. In this way, intergenerational trauma grows exponentially in a population when the coordinates of identification are removed from the grids of parents in an entire generation. The consecutive generations have no reference for psychological processing of trauma from either nation or concrete Others in their lives, either in the form of modeling which they can identify with or discourse which acknowledges their own identity formation. A bleak conclusion ensues, since we assume then that the child who has a parent that suffers both from trauma and has a prior neurotic structure, is bound to identify with the modeled neurotic structure in the absence of a proper intersubjective dimension with the state and in the presence of severe trauma. Since she cannot elaborate it in a normal, associative and meaningful way, she is also bound to repeat the same stunted way of processing said trauma ad infinitum and ad naseum. That is unless there is a restoration of the original relationship between subject and Other in which this Other must take a supporting and a mirroring position thus ending the vicious cycle once and for all (Verhaeghe, 2005). Analysis and Conclusions Schulze (1999) summarizes the psychological-historical condition of the Arab-Israeli conflict well when she says that, while all parties to the conflict knew the broad parameters of negotiations, the obstacles to negotiations seemed insurmountable: seven decades of Jewish-Arab relations riddled with mistrust, broken promises, violence, hatred and almost mutually exclusive interpretations of history. She goes on to conclude that, the psychological gap between the parties led to an absence of official and direct negotiations. (Schulze, 1999, p. 94) Arising from this historical sense of distrust, filled with broken treatises and betrayals that render discourse obsolete and damaged, dialogue has become paralyzed and mutual annihilation anxiety has ensued. Proper mirroring and acknowledgement have suffered as the symbols of Other-denial are sustained--walls go up and checkpoints prevail. As long as each group has an over-determined preoccupation with their own suffering which prevents them from addressing the Other as a necessary mirror through which their own necessary identity is determined, the situation will remain in a constructively mute but destructively verbose stalemate. If the relationship between Israel and the Palestinian Authority were to be considered as an analytic treatment, we would say that currently it is in a state of impasse, of rapturous awaiting repair. (Robinson, 2003) Still more troublesome is the fact that Palestinians and Israelis are not post-traumatic but in-traumatic both [living] in a kind of life-numbing shock (Helen Silverman, 2004). This statement is significant because it reasserts that the state of trauma in this part of the Middle East is ongoing as a way of life. It never ends and as such it reinforces the idea of the vilified Other which must be avoided at all cost, to the detriment of all parties involved. Furthermore, by sustaining an atmosphere of unmetabolized trauma where there is a daily loss of the others and ones own subjectivity (because of the fundamental negation of the other), the stage is set, not for traumas undoing, but for its perpetual repetition as each side holds a monopoly on the fixation of self as victim. Jonathan Lear (1990) describes how the meanings and memories that shape a persons outlook on the world do not lie dormant in the soul; they are striving for expression. If we are to take this as a simple way of expressing Freuds central thesis, then there is reason to think that the way in which almost half of Palestinian children think about the traumatic incidents in their lives (both in memory and daily occurrence) is stunted and abnormal simply because there is no expression other than within the silent horror of PTSD symptomatology. This renders a whole generation of young people, which is living in a state of statelesness, displacement, violence, fear, anxiety, and more, usually unable to process this overwhelming avalanche of arousal. This in effect perpetuates and exacerbates the problem as this form of coping (or non-coping) will also be transmitted intergenerationally as the prime and only known model for proper Palestinian psychological processing. There is reason to believe that children are a strong metaphor, if not literal representation, of the nation of Palestine as a whole. Not only do they represent the future leaders and parents of the up-and-coming Palestinian generations, but they also embody the national struggle in all that it suffers and entails. This bottom-up symbolization of the collective psyche of a people is possible in the Palestinian case because of the way in which

the Palestinians have been isolated by an apartheid-like system, providing uniform life-conditions for most who consider themselves Palestinian. 2 Arthur Koestler wrote: If power corrupts, the reverse is also true; persecution corrupts the victims, though perhaps in subtler and more tragic ways. Ultimately, this is the present and continuing tragedy that unremitting oppression has caused in the Palestinian population. Yet, it must be stated clearly that the solution will only comeand it is a difficult task indeedwhen both sides are ready to mirror each other as rooted and safe subjects. They must do so by way of acknowledging each others subjectivity in discourse, narrative, and action. This will entail the even more onerous task of identifying directly with the source of the problem. In affirming mutual blame, the monstrosity of each will be confirmed along with the humanity of each, possibly creating the lifeaffirming conditions to once again exist as proper subjects free from violence and trauma.

In a further study, one would want to make the distinction between the conditions of life of those who are Arab-Israelis, those who lived in the occupied territories (Gaza and the West Bank), and those who are exiled refugees in neighboring countries.

References Afana, A., Dalgard, O. S., Bjertness, E., Grunfeld, B., & Hauff, E. (2002). The prevalence and associated sociodemographic variables of post-traumatic stress disorder among patients attending primary health care centres in the Gaza strip. Journal of Refugee Studies, 15(3), 283-295. doi:10.1093/jrs/15.3.283 Apfel, R. J., & Simon, B. (2005). Trauma, violence, and psychoanalysis . The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 86, 191-202. American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistic manual of mental disorders (4th edition text revision). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC. Boothby, N. Upton, P., & Sultan, A. (1992). Children of Mozambique: The cost of survival (Special issue paper). Washington, DC: U.S. Committee for Refugees. Burge, G., (2003). Whose Land? Whose Promise?. New York: Pilgrim Press. Elbedour, S., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Ghannam, J., Whitcome, J. A., & Hein, F. A. (2007). Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety among Gaza Strip adolescents in the wake of the Second Uprising (Intifada) . Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 719-729. De Jong, J. T., Komproe, I. H., Ommeren, M. V., Masri, M. E., Araya, M., Khaled, N., et al. (2001). Lifetime events and post-traumatic stress disorder in 4 postconflict settings . The Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(5), 555-562. Hamama-Raz, Y., Solomon, Z., Cohen, A., & Laufer, A. (2008). post-traumatic stress disorder Symptoms, forgiveness, and revenge among Israeli Palestinian and Jewish adolescents . Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(6), 521-529. Lear, J. Love and its place in nature: A philosophical interpretation of Freudian psychoanalysis. (1990). London: Yale University Press. Paris, J. (2000). Predispositions, personality traits, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 8, 175-183. Quist, N., & Loewald, H. (2000). The Essential Loewald. City: Univ Pub Group. Quota, S., & Odeh, J. (2005). The impact of conflict on children: The Palestinian experience . Journal of Ambulatory Care Management , 28(1), 75-79. Quota, S., & Sarraj, E. (2004). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among Palestinian children in Gaza strip . Arabpsynet Journal, 8-13. Rabinowitz, D., & Abu, B. (2005). Coffins on Our Shoulders. Berkeley: University of California Press. Robinson, L. H. (2003). A Psychoanalytic Assessment of the Current Phase of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Journal for the Psychoanalysis of Culture and Society, 8(1), 153-156. Savjak, N. (2000). Sarajevo 2000: the physical consequences of war: Results of empirical research from the territory of former Yugoslavia. In S. Powell & E. Durakovic-Belko (Eds.), Displacement as a factor causing posttraumatic stress disorder (pp. 42-47). Sarajevo: University of Banja Luka. Retrieved April 2, 2009 Silverman, H. (2004). The Middle East crisis: Psychoanalytic reflections. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85, 1265-1268. Schulze, K., (1999). The Arab-Israeli Conflict. New York: Longman.

Thabet, A. A., Tawahina, A. A., Sarraj, E. E., & Vostanis, P. (2008). Exposure to war trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder among parents and children in the Gaza strip . European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17, 191-199. doi:10.1007/s00787-007-0653-9 Verhaeghe, P., & Vanheule, S. (2005). Actual neurosis and post-traumatic stress disorder: The Impact of the Other . Psychoanalytic Psychology, 22(4), 493-507. doi:10.1037 Verlag, S. (2003). Prevalence and determinants of post-traumatic stress disorder among Palestinian children exposed to military violence . European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 12, 265-272. Zizek, S. (2006). Jacques Lacan's Four Discourses. Lacanian Ink. Retrieved April 23, 2009, from http://www.lacan.com/zizfour.htm Zizek, S., (2008). Violence: Big Ideas/Small Books. New York: Picador.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Impact of Training On The Performance of Employeees in The Public Sector - A Case Study of MoWTDokument56 SeitenImpact of Training On The Performance of Employeees in The Public Sector - A Case Study of MoWTJJINGO ISAAC100% (2)

- Whom Then Does Christianity Negate?Dokument2 SeitenWhom Then Does Christianity Negate?Samuel Díaz FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whom Then Does Christianity Negate?Dokument2 SeitenWhom Then Does Christianity Negate?Samuel Díaz FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian ChildrenDokument8 SeitenA Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian ChildrenSamuel Díaz FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian ChildrenDokument8 SeitenA Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian ChildrenSamuel Díaz FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian ChildrenDokument8 SeitenA Psychoanalytic Understanding of PTSD in Palestinian ChildrenSamuel Díaz FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is There A Scientific Formula For HotnessDokument9 SeitenIs There A Scientific Formula For HotnessAmrita AnanthakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reinforcement Learning For Test Case Prioritization-Issta17 0 PDFDokument11 SeitenReinforcement Learning For Test Case Prioritization-Issta17 0 PDFAnonymous V8m746tJNoch keine Bewertungen

- PWC Interview Questions: What Do You Consider To Be Your Strengths?Dokument2 SeitenPWC Interview Questions: What Do You Consider To Be Your Strengths?Karl Alfonso100% (1)

- Process Mapping: Robert DamelioDokument74 SeitenProcess Mapping: Robert Dameliojose luisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recruitment and SelectionDokument3 SeitenRecruitment and SelectionMohit MathurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2 For 2b Mathematical Content Knowledge Last EditionDokument9 SeitenAssignment 2 For 2b Mathematical Content Knowledge Last Editionapi-485798829Noch keine Bewertungen

- Infosys Ar 19Dokument304 SeitenInfosys Ar 19shaktirsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Last Week JasonDokument4 SeitenLast Week JasonGieNoch keine Bewertungen

- V20 - Diablerie Britain PDFDokument69 SeitenV20 - Diablerie Britain PDFEduardo CostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Observational Tools For Measuring Parent-Infant InteractionDokument34 SeitenObservational Tools For Measuring Parent-Infant Interactionqs-30Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lab 8Dokument5 SeitenLab 8Ravin BoodhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kortnee Wingler Professional ResumeDokument1 SeiteKortnee Wingler Professional Resumeapi-413183485Noch keine Bewertungen

- Marxism and Literary Criticism PDFDokument11 SeitenMarxism and Literary Criticism PDFUfaque PaikerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Institutional PlanningDokument4 SeitenInstitutional PlanningSwami GurunandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Social Media in Academic Performance of Selected Grade 11 Students in STI College Novaliches SY 2018-2019Dokument28 SeitenEffects of Social Media in Academic Performance of Selected Grade 11 Students in STI College Novaliches SY 2018-2019Aaron Joseph OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Summary Quest For IntrapreneurshipDokument4 SeitenExecutive Summary Quest For IntrapreneurshipJan-Dirk Den BreejenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Confidence, and The Ability To InfluenceDokument15 SeitenSelf Confidence, and The Ability To InfluenceSOFNoch keine Bewertungen

- GFPP3113 Politik Ekonomi AntarabangsaDokument11 SeitenGFPP3113 Politik Ekonomi AntarabangsaBangYongGukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ongamo Joe Marshal - What Has Been Your Experience of LeadershipDokument14 SeitenOngamo Joe Marshal - What Has Been Your Experience of LeadershipOngamo Joe MarshalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dance Movement TherapyDokument5 SeitenDance Movement TherapyShraddhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cross Cultural ManagementDokument2 SeitenCross Cultural ManagementMohammad SoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qualifications of Public Health NurseDokument2 SeitenQualifications of Public Health Nursekaitlein_mdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gilmore Otp and OfpDokument13 SeitenGilmore Otp and Ofpapi-377293400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rodowick Impure MimesisDokument22 SeitenRodowick Impure MimesisabsentkernelNoch keine Bewertungen

- 138 PDFDokument398 Seiten138 PDFddum292Noch keine Bewertungen

- ACR PDF Legal SizeDokument2 SeitenACR PDF Legal SizeSAYAN BHATTANoch keine Bewertungen

- MPA LeadershipDokument3 SeitenMPA Leadershipbhem silverioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive Psychology Case StudiesDokument6 SeitenCognitive Psychology Case Studieskrystlemarley125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Specific Learning DisabilitiesDokument22 SeitenSpecific Learning Disabilitiesapi-313062611Noch keine Bewertungen