Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Enhancing Bilingual Education in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger

Hochgeladen von

Shenandoah SampsonOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Enhancing Bilingual Education in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger

Hochgeladen von

Shenandoah SampsonCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Enhancing the Language of Instruction Model in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger

A801 Final Paper HUIDs: 20828617 50828328 20828064

STEP 1: DEFINE THE PROBLEM In this policy recommendation, we address the issue of poor quality education in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, due to the fact that students primary language is not the same as the language of instruction. Though these countries have taken steps to address this deficiency, only a limited number of communities have benefited. All three countries are located in the Sahel, the arid region just south of the Sahara Desert, are similar in economic and social measures, and have comparable education systems. Like many former colonies in the region, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger retained French as their official language after independence from France, even though the majority of their citizens speak native languages. This is partially the reason why their education systems produce low quality outcomes, as students cannot grasp content in a language they never effectively master. The regional governments all face similar problems in educating a populace who are mostly comprised of subsistence farmers, and who are poorly served by the current school system. According the World Bank (2011), school life expectancy ranges from four years in Niger to seven years in Mali, even though each country maintains compulsory education through middle school. Though net primary enrollment rates are fair, ranging between 54 61% (UIS, 2009), self-reported attendance rates demonstrate abysmal results, as 40.6% of primary school students attend school in Mali, 36.5% in Niger, and 42% in Burkina Faso (MICS & DHS, 2006). Implications for this shortfall are not only academic, but also social, political, and economic. Accordingly, these three governments in the Sahel face serious challenges in implementing an education policy that addresses the needs of their citizens. In this report, we have chosen to implement a model of bilingual education that will improve upon the existing education structure. Currently, the youth literacy rates in these countries are between 36.5% in

Niger and 39.3% in Burkina Faso (UIS, 2005; UIS, 2007). To address these problems, each country has individually initiated experimental bilingual schools which have shown promise for student achievement. Nonetheless, effective policies that encourage widespread adoption of these successful programs have not been implemented. This policy recommendation aims to provide a template for these governments to scale up their bilingual programs and also to attract international support and funding. There are a number of international agencies already supporting bilingual education in these countries who will be supportive of efforts to scale-up these programs. By using Eugene Bardachs eightfold path to structure our findings and subsequent recommendation, (Bardach, 2009) we aim to systematically address the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats within the three education systems language of instruction policies. After defining the problem, both broadly and specifically for each individual context, we will present research in Step 2 from similar countries, in which we identify successful methods to prepare students to learn in a language that is not their mother tongue. In Step 3, we present four language of instruction models, and in Steps 4 through 7, we will establish critera to identify the most appropriate linguistic model, then evaluate each option based on those critera. Lastly, in Step 8, we will detail our recommendation of the best model for Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. In this, we aim to create a clear picture of what the policy should accomplish if the recommendation is adopted unilaterally across the region. Country Backgrounds: The Status of Education and Bilingual School Experimentation Burkina Faso While French is the official language of instruction, it is spoken regularly by just 10-15% of the population (Lavoie, 2008b). Most children are taught in French from the first year of

primary school. Unfortunately, many students fail to obtain sufficient mastery of French to succeed academically, which contributes to the poor educational outcomes experienced in the country. Although there are 68 languages in Burkina Faso, 90% of the population can speak one of 14 national languages (Lavoie, 2008b). In 1996 the government of Burkina Faso passed a law allowing the use of languages other than French in public schools (Lavoie, 2008). Burkina Faso has a primary completion rate of just 43% (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2009). Only 44% of male students and 60% of female students can read a French sentence by grade five (DHS, 2003). Eleven percent of primary students must repeat a grade each year (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2009). Monolingual schools are still primarily designed to prepare students for administrative careers, even though 80% of Burkinab are primarily engaged in subsistence farming (Lavoie, 2008). In 1994, the government of Burkina Faso acknowledged that its education system was not attuned to the social and economic realities of the country and was too costly, and thus, inefficient (UNESCO, 2007). As a result, a bilingual program was piloted in 1994. The results of the bilingual schools have been impressive. From 1998 to 2007 bilingual students pass rates on the national Primary School Certificate exam averaged 78.16%, while the average national performance was just 65.69% (UNESCO, 2007). Evaluators reported that bilingual schools were able to better utilize scarce resources due to higher success rates and lower repeat and dropout rates (Vachon, 2007). Eight national languages are currently used in 110 bilingual schools across Burkina Faso (Lavoie, 2008). Mali Many national languages have been introduced into schools throughout Mali over the past 25 years, though French is still the only official language, and used overwhelmingly for

instruction across all levels of academia (Tamari 2009). There are over 55 local languages and dialects spoken throughout the country, and approximately 80% speak Bamanankan (Bambara) (Traore 2001). Accordingly, the World Bank (2011) rates Mali 0.87 out of 1.0 on the language diversity index, indicating extensive linguistic heterogeneity. French was employed exclusively until 1979, when four schools near the semi-rural town of Fana began experimenting with instruction in Bambara (Mbodj-Pouye 2009). In 1994, the Malian government changed its policy, allowing for the preliminary use of mother tongue languages as a means to promote functional French literacy later in students academic lives. Those studying under the bilingual model in the experimental schools fare significantly better than children in traditional environments. Joshua Muskin found that children in a sample of experimental schools practicing bilingual education performed 40% better in literacy tests conducted in their own language (1999). These advantages were seen not only in reading, but also in mathematics scores. Despite proven successes resulting from these programs, difficulties arise in Malis efforts for large-scale implementation of bilingual education. The Malian government must overcome the popular opinion that literacy in local languages is not intrinsically valuable (Mbodj-Pouye 2009). Niger Though there are twenty-one living languages in the Republic of Niger, many of which are closely related, French has traditionally been used as the sole language of instruction in public schools. Currently, Niger has a language diversity index of 0.64, with eight national languages (World Bank 2011). Less than 10% of the population actually speaks French (Lewis, 2009). Experimental schools in the Republic of Niger were first introduced in 1973 to evaluate whether the utilization of local languages could improve student achievement and quality of

education in Nigerien schools (Albaugh, 2005). By 1998, there were forty-two of these schools across the country (Albaugh, 2005). That same year, the government introduced the Nigerien Education System Reform Law, which created a provision for which any of the five national languages could be used as the language of instruction in the first three years of primary school, to be followed by the phase-in of French (Chekaraou, 2010). Despite these progressive steps with legislation and experimental schools, the models have not been scaled up to a large extent. A study by the Ministry of Education from 2005-2007 found that just 6.4% of 6th grade students in 2005, and a mere 2% of 6th graders in 2007 were at the required level of competence in French (Chekaraou, 2010). However, recent evaluations of experimental schools paint a more promising picture of the of Nigerien students ability to succeed with the aid of their primary language. A study comparing the educational achievement of traditional schools and experimental schools found that students in experimental schools scored remarkably higher on the terminal primary school exam (Komarek, 2003). More recently, a study done by Chekaraou in 2004 found that in experimental Hausa-French schools, there was a more democratic atmosphere, increased teacher-student interactions, and more frequent classroom conversations. These schools have shown encouraging results, and Nigers main problem now is that progress toward expansion across the country has stagnated. STEP 2 - ASSEMBLE THE EVIDENCE Political and financial support from national government Political support is critical for the success of bilingual education policies. The role of the government is important even in small-scale bilingual education policies, given the sensitivities that surround them, and in order to scale up a program, the government must take a leading role. Nevertheless, government support for bilingual education is not guaranteed, and policies which

ignore the interests of politicians, bureaucrats, and administrators are unlikely to succeed (Kemmerer, 1994). In Cameroon, the Language in Education, Literacy and Development (CLED) Program targeted adults and children who were illiterate in their mother tongue (UNESCO, 2008). Although the CLED program produced positive results, the government remained reluctant to integrate mother tongue education into the mainstream system. Without the governments support, the programs impact has been limited in scope. A similar situation played out in Ghana, with different results. The Assistance to Teacher Education Programme (ASTEP), instituted in 1997, was intended to strengthen the usage of mother tongue instruction in the classroom, and improve the poor quality of Ghanaian education. The ASTEP program was successful in preparing teachers to teach mother tongue classes (Alidou, et al., 2006). Unfortunately, the Ministry of Education suddenly decided to revert to English-only instruction in 2002. In response, Ghanaian civil society, including teachers, students, local NGOs, and community leaders protested the new language policy. Following the protests, the government eventually reinstated bilingual education in Ghanaian schools in 2006. This case underlines the fact that government can be responsive to non-governmental actors, and that bilingual programs must have a strong base of support at the community level to be sustainable. Beyond political power, support from the government is also critical for financial reasons (Benson, 2010; Pinnock, 2008). While many developing countries governments rely upon foreign aid to fund bilingual education programs, the eventual goal is to fund and manage the programs independent of external support. Therefore, governments must take into account their own capacity to fund bilingual education programs in the long-term (Buhmann & Trudell, 2008). Vawda and Patrinos (1999) find that the greatest bilingual education expenses in Senegal are the costs of teacher education and bilingual materials production.

Governments may also be reluctant to implement bilingual education programs because they are concerned about incurring additional costs. However, if policy makers consider the costs relative to the quality of education produced, bilingual education often is much less expensive than traditional monolingual schools (Heugh, 2006). The education systems in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have very poor internal and external efficiency. That is, they do not maximize available resources to produce quality student learning, and students who do graduate find that they are poorly prepared for local job markets. Bilingual schools have been found to improve internal efficiency by improving student learning in the classroom (Traore, Kabore, & Rouamba, 2008). They can also increase external efficiency by making school curriculum more relevant to the lives students will lead when they leave the classroom (Kone, 2010). Community involvement Mother tongue education is intended to facilitate the participation of families and communities in the education of their children (Kouraogo & Dianda, 2008; Kone, 2010). Local languages create a bridge between schools and the communities which surround them, allowing for the two-way flow of knowledge between schools and communities. After finishing school, many children in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger stay in their local communities to work and raise families. Bilingual education allows the content they acquired to be more applicable and relevant to the lives they lead. There is significant research showing that mother tongue education greatly facilitates the participation of community members and parents in schools (Kouraogo & Dianda, 2008; Kone, 2010). This is especially true in the Sahelian countries, where citizens lack of French fluency is a serious barrier to communication between community members and schools. One example of a pilot bilingual education program that has done an excellent job of engaging with community members to establish new schools is in Burkina Faso (Lavoie, 2008).

Before a bilingual school is established, the Ministry of Education conducts several visits to the potential schools host-community to share information, allow community members to voice concerns, and finally to vote on whether to establish a bilingual school. This exemplary level of community participation, combined with visable positive results in student acheivement, has made these schools increasingly popular in Burkinab communities. Locally relevant curriculum/local language books Strong bilingual education programs do not simply translate the existing national curriculum into local languages. They also create new curricula that are more relevant to students lives and leverage the existing knowledge from local communities (Improving Quality, 2008; Policy Guide, 2010; Thomas, 2009). Successful bilingual programs allow teachers to collaborate with community members to create locally appropriate curriculum (Advocacy Brief, 2005; Thomas, 2009). The development of curricula locally engages communities in the education process, allows content reflective of local needs, and keeps costs much lower than they would be if materials were developed by foreign consultants (Ouane & Glanz, 2005). Since many parents cannot speak French, allowing education to take place in local languages also allows parents to be more supportive of their childrens academic lives (Ouane & Glanz, 2010). Multilingual Pedagogy for Teachers Currently, many classrooms in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and other multilingual contexts have been constrained to using safe talk, where oral and written communication is limited because of low competence on the part of both the teachers and the students (Benson 2002; Ouane & Glanz, 2005; Ouane & Glanz, 2010). Despite the prevalence of rote learning, most researchers and education policymakers are aware that learner-centered pedagogies are most effective. Consequently, as countries move toward successful multilingual models, training in

active pedagogy that capitalizes on communication between teachers and students will be necessary. (Buhmann & Trudell, 2008; Pinnock, 2008). Komarek (2003) writes that it is not simply switching the language that ensures learning, but that in order for multilingual models to be effective, it is crucial that governments develop adapted teaching and learning methodologies for the classroom. In particular, many teachers could benefit from learning about methodologies that facilitate the transfer of learning between languages given their relevance in mother tongue education classroom settings (Benson, 2010; Dutcher, 2004). Teachers in these settings need to understand language acquisition theory and practice in order to better structure their teaching (Benson, 2002). Not only is learning about the transfer between languages important for teachers in these new schools models, but teachers also need to be trained in how to capitalize upon the strengths of both students and community members of different linguistic backgrounds, particuarly in settings with multiple primary languages (Benson, 2010). In-Service and Pre-Service Teacher Training In scaling up already successful mother tongue education programs, alongside pre-service teacher training, it is extremely important to provide in-service teacher training to those already teaching in classrooms who must adjust to new methods of first and second language development (Advocacy Brief, 2005; Dutcher, 2004). The Policy Guide on the Integration of African Languages and Cultures into Education Systems (2010), argues that part of the capacity-building component of successful integration is ensuring that there are qualified staff to implement the scaling-up of this policy. Included in these trainings should be the revised mother tongue curricula and instructions on how to implement them in multilingual environments (Buhmann & Trudell, 2008). Support should be provided throughout a teachers career (Benson, 2010). In order to scale up, teachers will be needed who are competent in native languages, so

10

local or community teachers make ideal candidates. Eritrea is an outstanding example of a country that immediately reformed its teacher training schemes at the introduction of their mother tongue education program to enable people from a variety of ethnolinguistic groups to become teachers (Pinnock, 2008). Bolivia is also known for its exceptional efforts in recruiting female bilingual teachers within indigenous populations (Advocacy Brief, 2005). These two examples demonstrate the importance of providing flexible modes of entry to teacher training in order to gain a qualified population of teachers who speak local languages (Advocacy Brief, 2005; Thomas, 2009). STEP 3: CONSTRUCT ALTERNATIVES Before designing scaled-up implementation, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger must choose between four main policy options for language of instruction models: the monolingual model, the earlyexit model, the late-exit model and the maintenance model. Monolingual Model The monolingual model is one in which teachers conduct all instruction in French without the use of students primary language. The intention of this linguistic immersion is to encourage students to learn at a rapid pace in French. Research has shown that the immersion method can be effective when students live in communities where the official language is widely spoken, but because so few people speak French in the region, it is not an effective strategy (Pinnock, 2009). Unfortunately, monolingual programs have been found to lower expectations of what can be accomplished in the classroom, both for students and educators (Li 2007, 541). Also, because immersion is thought to encourage cultural domination, the main criticism of this pedagogy is that students do not learn or maintain their native languages and cultures. Opponents of this viewpoint argue that it is the responsibility of the family to relay cultural information to

11

the child, and that considering the extra costs of bilingual programs, immersion is the most efficient methodology (Li 2007, 546). Transitional Model: Early-Exit The early-exit transitional model is the most widespread approach to bilingual education in the francophone Sahel. It begins education in the mother tongue, and shifts to the dominant language of instruction after a short period of time. In the early-exit approach, students often start learning French in grade one or two. No later than grade four, they begin learning all content entirely in French. This model is often associated with convergent pedagogy; the concept that early primary education in ones mother tongue actually allows for increased French literacy later in life (Traore, 2001). The early-exit method is instrumental for students to grasp key concepts in the core subjects while learning and transitioning to the dominant language. Students often transition to French before they have gained significant competency in the local language (Kone, 2010). In multilingual communities, a common regional language can be used as the language of instruction. Since children are often much more proficient in a regional language than in French, these regional languages can also serve as an effective language of instruction in bilingual schools. Transitional Model Late-Exit The late-exit version of the transitional model is an expansion of the early-exit model, and aims to instill a deeper level of literacy in both the mother tongue and French. Though the goal of late-exit is to endow students with a more complete knowledge of their mother tongue, it is ultimately used to prepare students to study in French after graduating from primary school. Kone (2010) finds that acquisition of literacy in the mother tongue greatly improves a students ability to excel in content areas, as well as establish literacy in another language. This is due to

12

the extra time students spend on content in their native languages before subject material advances to more difficult levels. Maintenance Model In the maintenance model, students learn content in both languages simultaneously, maintaining instruction in the primary language through the end of secondary school. Baker (2006) shows this methodology to be more effective than transitional programs because maintenance allows the students to become proficient in both languages due to the expanded length of exposure. It is a more popular approach in areas with relatively low language diversity, as it relies heavily on equal instruction in two languages. Maintenance of both languages also serves to support minority cultures by incorporating the mother tongue equally into academic content and curriculum (Hornberrger, 2005). STEP 4 - ESTABLISH CRITERIA Cost effectiveness While existing literature highlights numerous examples of bilingual education policies that improved education outcomes, it is important to also consider the costs of these policies. Therefore, we explore the relative effectiveness of bilingual models and their subsequent costs. Common bilingual education costs include training for teachers on the new bilingual pedagogy and curriculum, bilingual materials development, and community outreach activities. By considering costs and benefits together we can draw much more accurate conclusions about the relative effectiveness of the different programs. While bilingual education policies may be somewhat more expensive to implement initially, if students learn more because of them the additional costs may be justified.

13

Sustainability The degree to which the different models of bilingual education can be sustainable is a critical consideration in selecting the appropriate model. Sustainable projects are ones which align the policies implemented by high level actors such as governments and international agencies with the interests of the people who will be affected by those policies (Gillies, 2010). When programs are truly sustainable and have significant community support they can survive political powers transitions which often undermine policies with weaker community support. Sustainable change requires feedback loops which maintain and extend a policy change over time (Gillies, 2010). For example, a well designed and implemented program will attract more community support for bilingual education, leading to increased government attention and funding for bilingual education, which in turn results in even better bilingual schools. School Participation Bilingual education programs aim to improve the low school participation rates in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Compared to other Sub-Saharan African countries, all three have very poor student enrollment and attendance, as well as higher dropout and repetition rates. Bilingual schools have been shown to frequently outperform their monolingual counterparts in these indicators. They have particularly increased school participation for members of certain groups, such as girls, children in very rural areas, and ethnic minorities. However, if bilingual programs are not perceived by parents as beneficial to their children, they can result in worse school participation rates. Therefore we evaluate the programs based on their ability to increase school participation while bearing in mind the need for political and community support under less than ideal conditions.

14

Achievement While participation is important, if students are not learning while they are in school, the system is not effective. There is substantial evidence that bilingual education programs produce better learning outcomes than monolingual schools. Their benefits are often greatest for children who are most in need of support, such as children from lower socio-economic groups, ethnic minorities, and girls. While it is clear that children learn best in their mother tongue, the fact remains that French is the language of economic and social importance for these countries. When examining the models of bilingual education we consider policies which will produce the highest level of student achievement in core academic subjects as well as in the French language. Politically feasible Government support is essential when evaluating the scalability of the bilingual education models. Even the best designed bilingual policy will fail if it lacks adequate political support. Some political actors may have economic or ideological oppositions to the adoption of bilingual education policies. For example, elites in the countries capitals may oppose bilingual education for their children, and have political influence well beyond their relative population. In selecting a bilingual model we consider the interests of the various political actors and their possible responses to the policies. Community support and participation Communities are the consumers of bilingual education, and regardless of the decisions made by policy makers they ultimately decide if they will enroll their children in bilingual schools. Their support for bilingual education is critical for the longevity and expansion of bilingual education programs. Some communities may already have negative perceptions of bilingual education. However, these negative perceptions can change over time, and a bilingual

15

policys success can depend on the type of model selected, and the degree to which communities are involved in design and implementation. We evaluate the bilingual models based on how likely they are to gain community support and to what extent they allow for community participation in the design, adoption, and day-to-day school activities. STEP 5 - PROJECT THE OUTCOMES Cost Effectiveness The monolingual model is less expensive because the government does not have to train new teachers or develop new curricula or materials. However, in the long run, it is extremely expensive in terms of the cost to educate students who drop out early or repeat many years of school. Any initial investment costs of bilingual models pale in comparison to this cost. The early-exit model is more expensive than the monolingual model because it requires the development and production of new materials and training new teachers, though it is the cheapest to finance of the three bilingual models. Nevertheless, the early-exit model is the least cost effective of the bilingual models because it necessitates new costs, while it does not produce the full benefits of a bilingual model. The late-exit model is slightly more expensive than the early-exit model. Due to economies of scale, once initial costs are incurred for development of materials in grades one through three, production for additional grades will not be much more expensive. Finally, the maintenance model may also benefit from economies of scale, but would be the most expensive of all models because it requires materials and teachers through the end of secondary school, while producing relatively similar benefits to those of a late-exit model. Sustainability The monolingual model is sustainable from the government perspective because it is already institutionalized and requires no additional management beyond current capacity to

16

maintain. However, this model is not sustainable in terms of the long-term development of these countries because it continues to produce students who are unprepared for the workforce. The early-exit model is relatively sustainable because it has already been established in experimental schools and has been proven effective, but is not sustainable in promoting an extremely effective model of bilingual education for students. The late-exit model requires more work initially, but in the long run, can be a very sustainable model for this region. The maintenance model is the most sustainable, although it requires more work up front like the late-exit model. It more fully supports a positive feedback loop by demonstrating its efficacy in producing a competant, biliterate workforce. Student Participation The monolingual model performs very poorly in terms of participation. Because most children do not understand French, or the culturally distant curriculum, students become frustrated and either do not attend or decide to drop out of school. The early-exit model promotes participation in schooling more effectively because it allows students to begin school with a language they understand. It also allows them the opportunity to learn the academic content rather than wasting time becoming frustrated by the language of instruction. The late-exit and maintenance models subsequently produce more participation because of their extended use of the primary language and protracted use of culturally relevant curricula. Student Achievement In relation to student achievement, the monolingual model performs the worst. Evidence shows that students frequently become literate in neither the primary language nor French, meaning they cannot master the academic content. The early-exit model demonstrates better results for achievement in both academic content and French language (Komarek, 2003;

17

UNESCO, 2007), though early withdrawal of content delivery in the primary language means that students sacrifice full literacy in their first language. The late-exit model also produces improved student achievement, while preparing students that are fully biliterate. Finally, the maintenance model is the most successful for student achievement because it produces students completely competent and prepared for the workforce in two languages (Alidou, 2006). Political Feasibility The monolingual model is the most politically feasible because it is already established, and seemingly promotes education in French, which both politicians and community members embrace as necessary for children. The early-exit model is also relatively feasible because successful models already exist. Many politicians embrace this model because it demonstrates successful results in the short term and then returns to French, which has more political support. The late-exit model is less politically feasible because it is not established in any of the countries, but could easily be added on to existing early-exit models. The maintenance model would encounter the most political resistance because many politicians and community members believe that the continued maintenance of the primary language through secondary would detract from education in French. Politically and logistically, this could be harder to implement as students move from relatively monolingual communities where they attended primary school to more diverse secondary schools where it would be difficult to choose one primary language for instruction. Finally, a maintenance model would be less feasible because it is likely that many politicians will oppose a model that encourages the maintenance of the primary language throughout secondary when students can attain a sufficient literacy level from a late-exit model. Community Support and Participation Currently, there is community support in the region for the established monolingual

18

model because many believe it more effectively supports the acquisition of French. This is gradually changing, however, with increased exposure to successful bilingual programs. To date, there has been relatively strong community support of early-exit models in the experimental schools of the region, and as community members see successful results, these schools become more institutionalized. The late-exit model may encounter some community resistance because of the misperception that mother tongue education takes away from their childrens mastery of French. In that regard, the maintenance model would encounter even more resistance because students would spend even less time learning in French. With the proper community awareness campaigns, however, it is likely that community members would be able to embrace late-exit and maintenance models the way they have embraced early-exit models. Many studies have shown that parents and community members are more involved in students education with bilingual schools, especially when they are involved in decision-making processes. STEPS 6 & 7: CONFRONT THE TRADEOFFS AND DECIDE In sum, the monolingual model is politically feasible and sustainable, enjoying community support. However, it would be extremely cost inefficient, would not promote longterm economic development, and would continue to exhibit insufficient student participation and poor results in student achievement. The early-exit model is politically feasible and has community support, given the fact that it is already established in many experimental schools, but it limits achievement and sustainability. It has been documented in many cases that utilizing the early-exit model sets countries up to fail in the long run. Although it shows positive shortterm results, there is a deficiency in promoting real transfer of learning between languages in such a short time period, and it is limited in the full range of benefits that a more extended bilingual model can provide for students (Ouane, 2005). The late-exit model is cost effective,

19

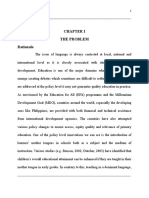

sustainable, politically feasible, and promotes excellent results for student achievement. Table 1, developed by Alidou et al. (2006), shows expected performance on high school language tests in the official language (e.g., French), based on the linguistic model used in students earlier grades (Appendix A). The table shows that the maintenance model achieves the best learning outcomes, while the late-exit transitional model creates the next best student achievement. We advocate the adoption of the late-exit model since it is much more sustainable and politically feasible to expand on a larger scale, while still producing strong improvements in student achievement. STEP 8 - TELL YOUR STORY Explanation of the preferred late-exit model After identifying the late-exit bilingual model as the most appropriate model for Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger it is now necessary to define the details of the policy. Late-exit models in which instruction is conducted primarily in the mother tongue most effectively promotes student learning. Since students who continue their studies beyond the primary cycle will be taught primarily in French, it is also important to introduce French as a subject early in childrens education. Therefore, we advocate for a system that begins with children learning 90% of the time in mother tongue and 10% of the time in French in grade one. Each subsequent year, the proportion of mother tongue instruction will decrease by 10%, and the time spent in French will increase by 10%, so by sixth grade students will spend 40% of their time learning in the mother tongue and 60% learning in French1. This will allow students to form a strong base of mother tongue literacy while also preparing them for studying in French in later grades. In middle and high schools that have a common primary language, mother tongue may still be offered as a subject in later cycles. Successful late-exit models also share a number of other characteristics.

1

i.e., Grade 1: 90% mother tongue/10% French; Grade 2: 80% MT/20% F; Grade 3: 70% MT/30% F; Grade 4: 60% MT/40% F; Grade 5: 50% MT/50% F; Grade 6: 40% MT/60% F

20

The bilingual curriculum should draw on community knowledge and involve those communities in curriculum creation (Kone, 2010). Educational materials should be developed in partnership with local experts in the communities where they will be used. New and current teachers must be thoroughly trained in both the content and delivery of bilingual curricula (Benson, 2010). Active teaching pedagogies should be developed to leverage the greatly increased communication potential of teachers and students in their mother tongues (Komarek, 2003). Finally, communities and parents must be supportive of bilingual education if the reform is to be sustainable. Support can be created by giving communities a voice in the development and adoption of bilingual schooling for their children. Implementation As Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger all have established pilot early-exit bilingual programs, the first step in moving toward a universal bilingual education system is to convert these programs into late-exit models. This will be relatively easy to do as the infrastructure and teachers comfortable with bilingual education are already in place. Another advantage of converting existing early-exit schools is that they already have the critical support of communities and political actors. In existing early-exit experimental schools education primarily takes place in French after grade three. Since instruction will be conducted in the mother tongue through grade six in the late-exit model, additional educational materials will have to be developed before the new model can be implemented. Since the bilingual curriculum must be relevant to the communities where it will be taught, the process of developing this material will be more time consuming than merely translating the existing national curriculum. Fortunately, pilot communities have already engaged in the process of developing the curricula used in the early-exit schools from grades one through three, so repeating the process to develop materials

21

for grades four through six should be managable. Bilingual teachers who are currently accustomed to transitioning to French after grade three will need to be trained on how to continue teaching in the mother tongue through grade six. This in-service training will focus on improving teachers ability to deliver the new mother tongue curricula in grades four through six. The trainings will also be an opportunity to train teachers on active teaching pedagogies, or to reinforce those teaching methods for bilingual teachers already familiar with them. The end goal of this initiative is not merely the establishment of a limited number of lateexit pilot schools, but the systematic reform of language policy in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Before the program can be scaled up it is critical that there is strong empirical evidence demonstrating the efficacy of the late-exit model. This evidence will both strengthen the political support base for the reforms and engender the support of local communities. Therefore we must determine the appropriate amount of time necessary between the conversion of the experimental early-exit schools into late-exit schools, and the targeted date for national implementation, assuming the research on the pilots supports this decision. The transition cannot occur until sufficient data has been collected on the late-exit pilots, while at the same time it is important that momentum for system-wide change be maintained from the pilot stage through scale-up. We propose a nine-year period between the implementation of the late-exit pilot schools and the targeted national scale up date. Nine years will allow students starting school in grade one to complete the primary cycle, and careful data can be gathered on their progress. Since children in the current early-exit schools are already learning in their mother tongue, students in grade three will be able to continue in their mother tongue under the late-exit model in grades four through six. This allows for data collection on those students who continue onto middle school and high school. Because research has found gains from some early-exit programs

22

dissipate with time, Alidou states that evaluations of bilingual education programs must measure student educational outcomes beyond the time students are actually engaged in bilingual education study (Alidou, et al., 2006). While the literature indicates that late-exit models are much more likely to create lasting achievement gains, it is still critical that this be shown to be the case in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. If the pilot late-exit schools are successful, the next step will be to conduct an extensive community outreach campaign. Bilingual programs are most successful when communities are involved in the implementation process of bilingual education. While the objective is for bilingual education to be an option for every community in the region, we recognize that bilingual education may not be desired by or appropriate for certain communities. Therefore the process of scaling up bilingual education will be participatory and community-driven. The community outreach strategy currently used for bilingual schools in Burkina Faso will be extended to Mali and Niger. Since some community members may have negative preconceived ideas of bilingual education, outreach workers will need to dispel some misperceptions. To do so, they will follow the Switch framework, a model developed by Heath and Heath (2010) that outlines the steps toward initiating positive change. This is accomplished by directing the rider (the rational decision-maker), motivating the elephant (peoples emotional and instinctive side), and shaping the path (easy steps people can follow for enacting change). To direct the rider, outreach workers will inform communities about the successes of bilingual education. Since the most common community concern about bilingual education is that it will limit childrens future opportunities, emphasis will be placed on showing that the late-exit model produces greater proficiency in both mother tongue and French language proficiency. To move the elephant, outreach workers will paint a picture of a community where student learning is not removed

23

from its surroundings, where students and teachers are able to express themselves completely, and where students learn, thrive, and are equipped to succeed once they leave school. Finally, communities will be shown the path. Community and school leaders will have opportunities to visit existing pilot schools and will be told about the process of converting their monolingual school to a bilingual school. Following the initial information session communities will be given the opportunity to deliberate and formulate questions for a follow-up meeting. During the follow-up meeting additional community concerns will be addressed. Finally, communities will vote on the conversion of their monolingual school into a bilingual school. Those communities that decline adopting the bilingual model will have the possibility of converting their schools in subsequent years. Giving communities the choice of transitioning is in part what makes the bilingual reform so sustainable. Communities are not disempowered by being required to have mother tongue schools. Moreover, if they observe positive results from bilingual schools in nearby communities they may be convinced to adopt bilingual education in the future. This participatory strategy will help avoid the formation of organized opposition to bilingual schools. While the community outreach effort is ongoing, the government must integrate bilingual education policies into its teacher recruitment and training procedures. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger will need to modify their current recruitment and placement procedures so more teachers are recruited from a range of linguistic groups. Currently, teachers are often assigned teaching positions by the government without regard to geographic origins or native languages. In order for bilingual education to function, schools need teachers who are fluent in the local language. Teacher colleges should integrate bilingual teaching methodologies into their curriculum. Current teachers in monolingual schools that will be converted into bilingual schools will need

24

in-service training to prepare help them to teach in local languages. Both pre-service and inservice trainings should focus on teaching mother tongue curricula designed for the communities where teacher are posted and preparing teachers to work multilingual environments (Buhmann & Trudell, 2008). The governments must play a leading role in the scale-up of bilingual education. For any policy reform to be successful, a national government must firmly support the policy and require its bureaucracy to implement the reform (Kemmerer, 1994). It must also ensure that regional governments are also supportive of the change. While bilingual education increases engagement and empowerment in local communities, political decentralization has not always benefited bilingual movements. Bilingual reforms can be easily weakened at the regional level, so maintaining the strong support of the national government is critical (Heugh, Benson, Bogale, & Yohannes, 2006). While this progressive reform will receive substantial financial and technical support from international development agencies supportive of bilingual education, it is also critical that the governments assume as much responsibility for the management of bilingual education as possible. Funds provided by international agencies would be given in the form of direct government budgetary support, and the governments would then fund the reforms out of their own education budgets. In the past international organizations preferred to bypass governments and fund development projects directly due to concerns about financial mismanagement. However, there is a growing consensus that such strategies undermine the longterm sustainability of the programs they intend to protect (Barder, 2009). When governments are directly responsible for managing bilingual education, the reforms will be far more likely to succeed and gain lasting support within the political establishment.

25

Conclusion As Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger strive to create successful educational systems that take into account the needs and concerns of multilinguistic learners, it is imperative that they bear in mind criteria that will scaffold effective outcomes. In response to the varied challenges faced by these governments, we have identified a bilingual policy that realistically addresses future costs and tradeoffs. Our chosen program, a late-exit transitional model, aims to facilitate literacy in mother tongue languages, then use that knowledge as a base from which to master French. This will enable citizens to participate more fully in the national and global economies by equiping them with the necessary tools for productivity within and outside their home communities. The success of this policy depends on the evaluation of pilot late-exit schools, the committment of relevant parties and multilateral participation from stakeholders. With the focused implementation of the above recommendation, and the support of stakeholders, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have an opportunity to create new opportunities for their citizens. As supportive infrastructure expands, more and more children would become literate in their local language, promoting local empowerment and the capacity for cultural conservation. Children would become literate in their first language before mastering French, which would allow them to pursue jobs in the local economy. Effective instruction of the mother tongue and French would then encourage students to enroll and stay in school, creating a positive feedback loop between literacy and scholastic achievement. Because of supportive pedagogies, students would be able to grasp key concepts in a language they comprehend before progressing to more complicated material. This an attainable reality in which the governments of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger can elevate their citizens learning capacity, enabling them as selfconfident, productive citizens.

26

APPENDIX A: Table 1: Expected Scores for Official Language Subject Test by Grade 10-12 by Bilingual Model

70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 %

L2 medium Mainstream plus L2 pullout

1 Subtractive / Monolingual

L1 for 2-3 years then switch to L2

L1 for 2-3 years plus specialised L2 each subject double teaching time

2b Early-exit transitional

L1 for 6/7 years then L2 medium

Dual medium (L1 only 5-6 yrs, L1 +L2 MOI from 7 th yr.)

P P

L1 medium throughout plus good provision of L2 as subject

4b Additive / Maintenance

TYPE

2a Early-exit transitional

3 Late-exit transitional

4a Additive / Maintenance

Source: Alidou et al., Optimizing learning and education in Africa the language factor, 2006

27

References Advocacy brief: Mother tongue-based teaching and education for girls. (2005). Alanis, I., & Rodriguez, M. A. (2008). Sustaining a Dual Language Immersion Program: Features of Success. Journal of Latinos and Education, 7(4), 305-319. Albaugh, E. (2005). The colonial image reversed: Advocates of multilingual education in Africa. International Studies Quarterly, 53(2), 289-420. Alidou, H., Boly, A., Brock-Utne, B., Diallo, Y., Heugh, K., & Wolff, E. (2006). Optimizing learning and education in Africa - the language factor. Paris, France: Association of the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA). August, D., & Shanahan, T. (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners. Mahwah, New Jersey: LEA. Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Bamgbose, A. (2004). Language of instruction policy and practice in africa. Bardach, E. (2009). A practical guide for policy analysis: The eightfold path to more effective problem solving. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. Barder, O. (2009). Beyond planning: markets and networks for better aid. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Barrak, Anissa. (n.d.). Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie. Retrieved September 28, 2011 from http://www.francophonie.org/English.html. Benson, C. J. (2002). Real and potential benefits of bilingual programmes in developing countries. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 5(6), 303-317. Benson, C. (2010). How multilingual African contexts are pushing educational research and practice in new directions. Language and Education, 24(4), 323-336. Beykont, Z. (1997). Refocusing school-language policy discussions. In W. Cummings, & N. McGinn, International Handbook of Education and Development: Preparing Schools, Students, and Nationals for the Twenty First Century. New York: Pergamon. Brock-Utne, B. (2001). Education for all - in whose language? Oxford Review of Education, 27(1). Buhmann, D., & Trudell, B. (2008). Mother tongue matters: local language as a key to effective learning. Paris, France: UNESCO.

28

Chekaraou, I. (2004). Teachers' appropriation of bilingual educational reform policy in subSaharan Africa: A socio-cultural study of two Hausa-French schools in Niger. Indiana University. Chekaraou, I. (2010). Improving quality in basic education in Niger: Initiatives, implementation and challenges. 1-20. Chiatoh, A. (2006). Barriers to Effective Implementation of Multilingual Education in Cameroon. In E. Chia, African linguistics and the development of African communities. Dakar, Senegal: Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa. Christian, D. (1996). Two-way immersion education: Students learning through two languages. The Modern Language Journal, 80(1), 6676. Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 222-251. Cummins, J. (1991) Interdependence of First and Second Language Proficiency in Bilingual Children. Cambridge. DHS. (2003). Demographic and Health Surveys Dataset. Retrieved from http://www.measuredhs.com/ Dutcher, N. (2004). Expanding Educational Opportunity in Linguistically Diverse Societies. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. Dutcher, N. Language policy and education in multilingual societies: Lessons from three positive models. Barcelona. Dutcher, N. & Tucker, G. R. (1997). The use of first and second languages in education: A review of international experience. Pacific Islands Discussion Paper Series, (1), 1-47. Education Policy and Data Center. (2011). Educational Indicators in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. Retrieved from http://epdc.org/ Freeman, R. D. (1998). Bilingual education and social change. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters. Gillies, J. (2010). The power of persistence: education system reform and aid effectiveness. Washington, DC: AED/Equip2. Heath, C. & Heath, D. (2010). Switch: How to change things when change is hard. NewYork: Broadway Books. Heugh, K. (2006). Cost implications of the provision of mother tongue and strong bilingual models of education. In H. Alidou, A. Boly, B. Brock-Utne, Y. Diallo, H. K, & E. Wolff,

29

Optimizing learning and education in Africa - the langauge factor. Paris, France: Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA). Heugh, K., Benson, C., Bogale, B., & Yohannes, M. (2006). Final report study on Medium of Instruction in primary schools in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Commissioned by the Ethiopian Ministry of Education. Hornberger, N.H. (2005). Student Voice and the Media of Bi(multi)lingual/Multicultural Classrooms. In T.L. McCarthy (Ed.), Language, Literacy and Power in Schooling (pp. 151 168). London: Lawrence Erlbaum. Hovens, M. (2002). Bilingual education in West Africa: does it work? International Journl of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 5(5), 249-265. Improving the quality of mother tongue-based literacy and learning: Case studies from Asia, Africa and South America. (2008). Bangkok, Thailand: UNESCO, 114-165. Kemmerer, F. (1994). Utilizing Education and Human Resource Sector Analysis. Paris, France: UNESCO. Komarek, K. (2003). Universal primary education in multilingual societies. 1-26. Kone, A. (2010). Politics of language: the struggle for power in schools in Mali and Burkina Faso. International Education, 39(2), 6-20. Kouraogo, P., & Dianda, A. (2008). Education in Burkina Faso at Horizon 2025. Journal of International Cooeration in Education, 11(1), 23-38. Lavoie, C. (2008). Hey teacher, speak black please: the educational effectiveness of bilingual education in Burkina Faso. The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 11(6), 661-677. Lavoie, C. (2008b). Famine ducative en Afrique, jai soif de comprendre: ducation bilingue au Burkina Faso. McGill Journal of Education, 43(1), 21-32. Lewis, P. (2009). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Li, B. (2007). From Bilingual Education to OELALEAALEPS: How the No Child Left Behind Ect has Undermined English Language Learners' Access to a Meaningful Education. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy, 14(3), 539-572. Muskin, J. A. (1999). Including local priorities to assess school quality: The case of Save the Children community schools in Mali. Comparative Education Review, 43(1), 36-63.

30

Muthwii. (2004). Language of instruction: a qualitative analysis of the perceptions of parents, pupils and teachers among the Kalenjin in Kenya. Language, Culture and Curriculm, 1532. Oeuvre Suisse dEntraide Ouvrire. (2011). OSEO LEcole Primaire Bilingue (EPB) Program. Retrieved 11 28, 2011, from http://www.oseo-burkina.bf/spip.php?article46. Ouane, A., & Glanz, C. (2005). Mother tongue literacy in sub-Saharan Africa. UNESCO Institute for Education. Ouane, A., & Glanz, C. (2010). Why and how Africa should invest in African languages and multilingual education. Hamburg, Germany: UNESCO. Pinnock, H. (2008). Mother tongue based multilingual education: How can we move ahead? Save the Children. Pinnock, H. (2009). Steps towards learning: A guide to overcoming language barriers in childrens education. London: Save the Children. Policy guide on the integration of african languages and cultures into education systems (2010). Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: ADEA & UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. Rose, P., & Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions, and Equity. (2007). NGO provision of basic education: Alternative or complementary service delivery to support access to the excluded create pathways to access. Research monograph no. 3. Online Submission. Roy-Campbell, Z. M. (2006). The state of african languages and the global language politics: Empowering african languages in the era of globalization. Selected Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. 1-13. Thomas, C. (2009). A positively plurilingual world: Promoting mother tongue education. State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2009. 83-87. Thomas, W. P., & Collier, V. P. (2003). The multiple benefits of dual language. Educational Leadership, 61(2), 6164. Traore, S. (2001). Convergent teaching in Mali and its impact on the education system. Prospects (Paris, France), 31(3), 353-371. Traore, C., Kabore, C., & Rouamba, D. (2008). The continuum of bilingual education in Burkina Faso: an educational innovation aimed at improving the quality of basic education for all. Prospects, 38, 215-225.

31

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2009). UIS Statistics in Brief. Retrieved 9 26, 2011, from http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/document.aspx?ReportId= 289&IF_Language =eng&BR_Country=8540&BR_Region=40540. Vawda, A., & Patrinos, H. (1999). Producing educational materials in local languages: costs from Guatemala and Senegal. International Journal of Educational Development, 287 - 299. Weyer, F. (2009). Non-Formal Education, Out-of-School Learning Needs and Employment Opportunities: Evidence from Mali. Compare: A Journal of Comparative & International Education, 39(2), 249-262. World Bank. (2011). [Interactive data visualization of development indicators in various fields] StatPlanet. Retreived from http://www.sacmeq.org/statplanet/.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- EdNotes Lang of InstructDokument4 SeitenEdNotes Lang of InstructChiso PhiriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neomap0909Dokument12 SeitenNeomap0909Rona Raissa Angeles-GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abdulwakil Hassen Omer ResearchDokument6 SeitenAbdulwakil Hassen Omer ResearchAbdulwakil HasenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engaging and Motivating FLL With Audiovisual AidsDokument14 SeitenEngaging and Motivating FLL With Audiovisual AidsMargaretNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research On Multigrade TeachersDokument43 SeitenResearch On Multigrade TeachersEly Boy AntofinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- French Language Education in Nigeria, Challenges and ProspectsDokument12 SeitenFrench Language Education in Nigeria, Challenges and ProspectsDerick AshuabuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENGLISH TEACHERS' PERCEPTIONS OF THE MOTHER TONGUE BASED EDUCATION POLICY IN THE PHILIPPINES Full Paper PDFDokument16 SeitenENGLISH TEACHERS' PERCEPTIONS OF THE MOTHER TONGUE BASED EDUCATION POLICY IN THE PHILIPPINES Full Paper PDFClaire dela Vega100% (1)

- MTB Education Enhances Grade 3 ReadingDokument14 SeitenMTB Education Enhances Grade 3 ReadingDanny TagpisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education 2015: Melanie A. Benitez ReporterDokument14 SeitenEducation 2015: Melanie A. Benitez ReporterDEBORA CHANTENGCONoch keine Bewertungen

- UNESCO PEFaL InfoDokument5 SeitenUNESCO PEFaL InfoJosephine V SalibaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mtbmle LagunaDokument89 SeitenMtbmle LagunaAngel DogelioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enhancing Learning of Children From Diverse Language BackgroundsDokument91 SeitenEnhancing Learning of Children From Diverse Language BackgroundsAdeyinka PekunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rachel Hsieh - Final PaperDokument28 SeitenRachel Hsieh - Final Paperapi-532470182Noch keine Bewertungen

- Major 9: Language Programs and Policies in Multingual Society Indigenous Language ProgramDokument3 SeitenMajor 9: Language Programs and Policies in Multingual Society Indigenous Language ProgramAngela Rose BanastasNoch keine Bewertungen

- French Language Education in NigeriaDokument14 SeitenFrench Language Education in NigeriaAdemola Michael100% (6)

- MTB-MLE Appropriateness in Urban AreasDokument10 SeitenMTB-MLE Appropriateness in Urban AreasChristina JazarenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language PolicyDokument36 SeitenLanguage PolicyCherry WestinNoch keine Bewertungen

- 105550-Article Text-286045-1-10-20140721Dokument14 Seiten105550-Article Text-286045-1-10-20140721may lachicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bilingualizing Linguistically Homogeneous Classrooms in Kenya Implications On Policy Second Language Learning and LiteracyDokument15 SeitenBilingualizing Linguistically Homogeneous Classrooms in Kenya Implications On Policy Second Language Learning and Literacyadrift visionaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19-175 - Yanagi 2Dokument29 Seiten19-175 - Yanagi 2Richann SahilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Studies of Educational SystemsDokument6 SeitenComparative Studies of Educational SystemsDan ZkyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 5 Professional Review BlogDokument3 SeitenAssignment 5 Professional Review Blogapi-508015406Noch keine Bewertungen

- Language Barriers in The ClassroomDokument13 SeitenLanguage Barriers in The ClassroomLyth LythNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Global Perspective On Bilingualism and Bilingual EducationDokument2 SeitenA Global Perspective On Bilingualism and Bilingual EducationcanesitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AGlobalPerspectiveonBilingualism PDFDokument5 SeitenAGlobalPerspectiveonBilingualism PDFradev m azizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Mother Tongue PDFDokument5 SeitenEffect of Mother Tongue PDFeto sintNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Mother Tongue PDFDokument5 SeitenEffect of Mother Tongue PDFApril OlmedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding of Mathematics in Cebuano vs. EnglishDokument8 SeitenUnderstanding of Mathematics in Cebuano vs. Englishpaulinavera100% (1)

- MTB MLE ResearchDokument62 SeitenMTB MLE ResearchJohn ValenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- THESISDokument37 SeitenTHESISMiah RM95% (104)

- Bilingual EducationDokument16 SeitenBilingual Educationapi-517763318Noch keine Bewertungen

- EEM115-Week2-HW1-Prelim-SALAMAT, SHIELA MAEDokument2 SeitenEEM115-Week2-HW1-Prelim-SALAMAT, SHIELA MAESalamat, Shiela MaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- RRL El6Dokument2 SeitenRRL El6Danica BuhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intensive French in bc-2Dokument4 SeitenIntensive French in bc-2api-270814276Noch keine Bewertungen

- NebaDokument24 SeitenNebadanila_izabelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PA00WG8FDokument5 SeitenPA00WG8FAnguyu JimmyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3b19 PDFDokument12 Seiten3b19 PDFZhavia ShyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mother-Tongue Based Multilingual EducationDokument60 SeitenMother-Tongue Based Multilingual EducationWinter BacalsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- History Foreign Language Policies ColombiaDokument38 SeitenHistory Foreign Language Policies ColombiaMariana RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language and Symbolic Violence in PakistDokument22 SeitenLanguage and Symbolic Violence in Pakistmuhammad7abubakar7raNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Yoruba As Language of InstructDokument13 SeitenEffect of Yoruba As Language of InstructOluwasegun SoluadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Case Against Arguments Obstructing Bilingual Education in South AfricaDokument26 SeitenThe Case Against Arguments Obstructing Bilingual Education in South AfricaNaziem MoosNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study of Bilingual Education in The PhilippinesDokument27 SeitenA Study of Bilingual Education in The PhilippinesPoseidon NipNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pursuit of Social Change in Nigeria: The Language Education AlternativeDokument6 SeitenThe Pursuit of Social Change in Nigeria: The Language Education AlternativedotunolagbajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Medium of Instruction in Ethiopian Higher EducDokument24 SeitenThe Medium of Instruction in Ethiopian Higher Educsamiranes167Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pupils' Performance Using Mother Tongue InstructionDokument9 SeitenPupils' Performance Using Mother Tongue InstructionLegencio MheganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Some Current Issues, Concerns and Prospects: Open File: Education in AsiaDokument8 SeitenSome Current Issues, Concerns and Prospects: Open File: Education in AsiaSIT ADAWIAHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Almario Villenueva DualLanguageDokument30 SeitenAlmario Villenueva DualLanguageVictorino Victorino ButronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine's Mother-Tongue-Based Multilingual Education and Language Attitude: Criticizing Mahboob and Cruz's Attitudinal SurveyDokument4 SeitenPhilippine's Mother-Tongue-Based Multilingual Education and Language Attitude: Criticizing Mahboob and Cruz's Attitudinal SurveyHanierose LaguindabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Strategies To Support Isixhosa Learners Who Receive Education in A Second/Third LanguageDokument12 SeitenTeaching Strategies To Support Isixhosa Learners Who Receive Education in A Second/Third LanguageAllistair MatthysNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bilingual and Mother Tongue Education in the PhilippinesDokument14 SeitenBilingual and Mother Tongue Education in the PhilippinesChromagrafx100% (1)

- For Prelim ExaminationDokument7 SeitenFor Prelim ExaminationJosel Gigante Caraballe100% (1)

- Implementation of MTBMLE in Pangasinan IDokument63 SeitenImplementation of MTBMLE in Pangasinan Isaro jerwayneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experiences of MTB-MLE Teachers in Southern LeyteDokument16 SeitenExperiences of MTB-MLE Teachers in Southern LeyteRica Mae Navarro MarlingNoch keine Bewertungen

- South Africa Education OverviewDokument5 SeitenSouth Africa Education Overviewybbvvprasada raoNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Language Education in Rural Schools of IndiaDokument18 SeitenEnglish Language Education in Rural Schools of Indiasoundar12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bilingual Policy EssayDokument3 SeitenBilingual Policy EssayJeph ToholNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept PaperDokument6 SeitenConcept PaperEdjay SuarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenVon EverandReading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Exploration of Philosophical Assumptions that Inform Educational Policy in Jamaica: Conversations with Former and Current Education MinistersVon EverandAn Exploration of Philosophical Assumptions that Inform Educational Policy in Jamaica: Conversations with Former and Current Education MinistersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Characteristics of Earth's BiomesDokument2 SeitenCharacteristics of Earth's BiomesGian TayamoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Form123academicbooklet 2Dokument16 SeitenForm123academicbooklet 2Mohamed AlamariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom DiscourseDokument3 SeitenClassroom Discoursechahinez bouguerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foundation of TeachingDokument9 SeitenFoundation of Teachingapi-403171908Noch keine Bewertungen

- Task 2-Peer Observation 1Dokument5 SeitenTask 2-Peer Observation 1api-490600514Noch keine Bewertungen

- Child and Adolescent DevelopmentDokument6 SeitenChild and Adolescent DevelopmentPascual GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adamawa State CSDA - Draft Report2Dokument261 SeitenAdamawa State CSDA - Draft Report2Justice OnuNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPH MachinesDokument8 SeitenRPH MachinesMOHD HASRUL ASRAF BIN OTHMAN MoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approaches To Teaching GrammarDokument60 SeitenApproaches To Teaching GrammarKristelle AllesNoch keine Bewertungen

- IELTS Prep Writing: Task 2: Hanif PreplyDokument26 SeitenIELTS Prep Writing: Task 2: Hanif Preplyluksisnskks929299wNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Physical Education Vi Sept 25Dokument3 SeitenDetailed Lesson Plan in Physical Education Vi Sept 25JOEL PATROPEZ100% (1)

- G6 LP Week 2 (Q1)Dokument3 SeitenG6 LP Week 2 (Q1)Ruthcie Mae D. LateNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTEL 7040 - Relection Paper (Week 7)Dokument4 SeitenCTEL 7040 - Relection Paper (Week 7)Jessica PulidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sundale Usd - Pra 5Dokument681 SeitenSundale Usd - Pra 5Michael SeeleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Little Bridge 1 ProgramaDokument77 SeitenLittle Bridge 1 ProgramaSilvia amaro0% (1)

- School Administration and Supervision (8616) : (Assignment 01)Dokument8 SeitenSchool Administration and Supervision (8616) : (Assignment 01)SajAwALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buatag Rating Sheet Cot2Dokument1 SeiteBuatag Rating Sheet Cot2marife buatagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploring Creative Leadership As A Concept - A Review of LiteratureDokument16 SeitenExploring Creative Leadership As A Concept - A Review of LiteratureRodhiana PhDNoch keine Bewertungen

- School Disaster Management Plan: (SDMP) S.Y. 2017-2018Dokument19 SeitenSchool Disaster Management Plan: (SDMP) S.Y. 2017-2018JakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Third Cot-Math 2Dokument3 SeitenThird Cot-Math 2Haidie Muleta100% (1)

- Oct.17 - Phrasesclauses and SentencesDokument5 SeitenOct.17 - Phrasesclauses and Sentencesmarinel de claroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson PlanDokument1 SeiteLesson PlanYogamalar ChandrasekaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Face Validity FormDokument15 SeitenSample Face Validity FormDavid GualinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced - and - Slow LearnersDokument16 SeitenAdvanced - and - Slow LearnersAnupEkboteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8603 (2)Dokument23 Seiten8603 (2)safaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 120 Unit9Dokument20 Seiten120 Unit9Nguyễn DuyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Field Study-Learning-Experience-1Dokument16 SeitenField Study-Learning-Experience-1Czai Lavilla80% (5)

- Teacher Preparedness For The Implementation of Competency Based Curriculum in KenyaDokument6 SeitenTeacher Preparedness For The Implementation of Competency Based Curriculum in Kenyayenm1621066Noch keine Bewertungen

- BOX: Henry Brown Mails Himself To Freedom Teachers GuideDokument3 SeitenBOX: Henry Brown Mails Himself To Freedom Teachers GuideCandlewick PressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dorset College Courses in English BrochureDokument16 SeitenDorset College Courses in English BrochureEtpsi Trabajo PsicologicoNoch keine Bewertungen