Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Sibuyan Mangyan Tagabukid

Hochgeladen von

Abe Bird PixCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Sibuyan Mangyan Tagabukid

Hochgeladen von

Abe Bird PixCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

~ ~

WWF

,

SIBUYAN

MANGYAN

TAGABUKID

Surviving In A Changing World

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

SuppOrt for the research and writing of this book was made

possible by the "Prot cring the Biodiversity of Me. Guit ing-guiting

through the Development of Su t ai nable Community Liveli hood

Enterprises" program of WWF-Philippines, which i funded by

the Directorate General for Int rnarional Cooperation (DGIS)

of the Netherbnds government.

A sabbatlw.lleave from my academic duries at the College of the

Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Manila provided

me with opportunitie to do extended fi eldwork in Sibuyan.

Our fieldwork would not have been frui tful without the ibuyan

Mangyan Tagabuki d of Gintak-an, Gi n-alan, Kabuylanan, Hagimit,

Layag and Panagintingan who guided llS in our journey to

understand thei r way of Iii .

I am also grateful to the many indivi duals wh gave support,

many ugge ti n and encouragement to finally finish this pr iec :

Miks Gul3.-Padilla, Chri sma Sa lao, Carmen Villasenor, Dr. C li

Boncan, Arnold Molrna Azurin, Aileen May Paguntalan, Trina Galido,

Edsel Ramirez Mel iza Joy Torres, Al fredo Principe II, Efren Isorena,

Perla E plel, Ninel Tayag, Rosmiah Mayo and Porti a Marasigan

and Marisel Dino and all t he staff of KKP Si buyan. Needless

to say, there are nameless others, all of whom should be absolved

of any error and shortcomings of this book.

Maramillg sa/arnot at mabuha}, kayong lahat!

Sabino G. Padilla, Jr., PhD.

A UNIQUE ECOLOGICAL NICHE WITH ONE OF mE WORLD'S HIGHEST CONCENTRATIONS OF BIODIVERSITY.

SINCE THE PLEISTOCENE, IT HAS BEEN SEPARATED FROM THE REST OF THE PHILIPPINES BY SURROUNDING

DEEP CHANNELS. THIS ISOLA TlON ENABLED

A NUMBER OF UNIQUE SPECIES TO FLOURISH

ON THE ISLAND. THE MOST REMARKABLE

FEATIJRE OF THE 456 -SQUARE KILOMETER

LAND IS AN UNDISTIJRBED FOREST AREA

OF 16,000 HECTARES. AT THE HEART OF THE

ISLAND IS MOUNT GUITING-GUITING, ONE

OF THE FEW PLACES IN THE PHILIPPINES

WHERE ONE CAN FIND A RANGE OF FORESTS,

FROM THE LOW MOUNTAIN FOREST TO THE

UPPER ALPINE FOREST.

IRONICALL Y, IN Tl-IIS ENVIRONMENT WHERE

DIVERSITY THRIVES, LIVES A GROUP STRUGGUNG

TO AFFIRM AND MAINTAIN THEIR ItIDIVIDUALITY

AS A PEOPLE.

The interior and upland areas of Sibuyan are inhabited by the Sibuyan

Mangyan Tagabukid, one of the least studied Philippine indigenous

peoples. Even for those who also live on the island, the Mangyan Tagabukid's

way of life is unfamiliar - as uncharted a territory as their island haven.

The Mangyan Tagabukid conununities use a set of established caregories

in distinguishing the "tunay na katutubo ng bukid" (genuine indigenous

people of the mountains ), as distinct from taga-ubos (lowlanders):

Individuals born and currently residing in the mountains, who

can trace their lineage to long-time residents of the mountains;

Individuals who cultivate fields il1 the mountains for their

subsistence;

Individuals who can only acquire fatui j" the mountains through

panoblion (inheritance); and

Lowlanders married to Mangyan Tagabukid.

Prehistoric data on Sibuyan and the Mangyan Tagabukid are wholly

unavailable. However, there are a number of burial caves on the i land

that contain artifacts such as ceramics, glass beads, wooden coffins, bones,

jars and pots.

Some scholars contend that the Mangyan Tagabukid may be the remnants

of [he original inhabitants of Sibuyan that sought sanctuary in the thickly

forested range to elude either the Spanish colonizers or the Mora slave-

w.ml1Z".. raiding forays from the 16t h to the

18th century.

Sihllyan MaJtgyall Tagabukid children

Spanish conquistadores led by Martin de Goiti reached Sibuyan as early

as rhe 16rh century. The Spanish expedition described Sibuyan as a "high

and mountainous land known to possess gold mines" and its natives,

"handsome", They were observed to "pai nt themselves, like those

of neighboring Banton Island".

Si nce this sketchy account of t he initial Spanish sighti ng, the Sibuyan

dwellers of the range have received scant attention, and no for mal

ethnographic investigation has ever been conducted on them.

The threat of Mora incursions was sparked by Spanish efforts t establish

domi nion over the southern Phili ppines and control the spread of Islam.

Punitive expeditions to Borneo, Sul u and Cotabato were not a deterrent

to Moro warriors raiding coastal communities under the colonial administration.

In 1649, Sibuyan, Romblon and Banton joined the rebell ion against

Spain that started in Palapag, Samar and spread to Mindanao.

In order to consolidate the colony, attempts were made to convert t he

non-Christians, or what they called infi eles, or infidels. The Recollect fathers

administered th conversion of the native population of Sibuyan and the

people of Romblon, CaJamianes, and Negros. In 1744, the pari sh priest

of the town of Cajidiocan made ser ious efforts to Christianize and resettle

these mountain dwellers to a poblacion, or central part of the town. He was

able to convince 218 Mangyan Taga bukid on condi tions t hat t hey

be exempted from paying tax for ten years and from rendering service

in the military and other government activities t hat required seafaring.

After t hey had begun converti ng the natives, the Spanish

colonizers classifi ed all the inhabitants of Sibuyan, Tablas and

Romblon as Mang)'an. Such broad cl assifi cation was probably

beca use of their proximi ty to Mindoro, whose inhabitants

identified themselves as Mangyan.

Al though this was false, as the Sibuyan Mangyan Tagabukid

have an i entity separate from the Mangyan of Mindoro, it stuck

through the centuries. Early impressions and labels based on the

friar chrorucles, on which many relied for information, have a long

lasting effect. An example is this excerpt from a report of the Order of Saint

Augustine Recollects in 1700:

" ... based on frequent accounts by the locals of" the island,

a large m4mber of infidels inhabit the mountains of the island

of Sibuyan, coming (rom the island of Mindoro. Those

accounts relate that a great number of said infidels, together

with their women and children lived for a long time on this

island, around the steep slopes of the mountains. There, they

lived a nomadic life that they were accustomed to in the

mountairlS of Mindoro ... "

Spanish historian Agustin de la Cavada Mendez de Vigo, in his Historia

Geografica, Geologica y Estadisti ca de Filipinas wrote on the tribes

in Caji diocan called Manguian, who are "submissive but livi ng savagely

in th mountains and who sustain themselves by means of robbery. Those

in Azagra are disobedienr and do not associate with the natives of thi s tOwn."

Aiter convincing the pagan t ribes who inhabited t he forest regions

of Sibuyan to submit themselves to th authority of the Spanish government

and convert to rhe Catholic religion, the upland vill ages of Princesa,

Ysabel and Espana were for med. Problems arose when m rchams came

to COntract the services of the inhabitants of these villages to coll ect

almaciga, wax and tar widely found throughout the island. Despite the

fact that these products f t hed high prices at that time, merchants paid

the Mangyan Tagabukid so little that there was never enough for these

people to meet thei r basic necessities.

Although an dfort was made by the Spanish poli tical -military

commandant at that tim to impose price conrrol on the forest products

and regulate trade, t he governor-general eventually ordered 0 leave

trade unrestricted. This made some of the inhabitant retreat once

again to higher ground.

More of them were for ed to go back to the mountains in s bsequent

year as Mangyan Tagabuki d vi ll ages located in the were

nor spared from the plagues and epidemics that struck almost the entire

archipelago in the years prior to World War 11. Others opted to rerrea

ecause of wartime roeities. In the ourse of time, due to their non-

participation in the colonized lowland society, they became an indigenous

people once again.

During the American colonial period, the Philippine Commission

created the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes (BNCT) under Act No. 253.

Its principal objectives ere to study the conditions of pagan tribes

and Muslim groups, recommend programs to the ivi l government,

and conduct t hnological studies in t e Philippines. It was later on

reorganized into the Ethnological Survey of the Philippines.

The BNCT lists the Sibuyan Mangyan among the indigenous groups

of th Philippines. However, ap rr from acknowledging their existence

In Sibuyan, the bureau has not done anything concrete for the group.

Subsequent reports reflect how littl e was known about the Sibuyan

Mangyan Tagabukid.

In the 1901 Report of the Philippine Commission to the President,

a section entirely dedicated to the description of the island of Sibuyan

descri bed the natives as follows:

"The Mallguianes who live i1l the mountains are quite pacific,

btlt not at all addicted to work, and so dirty that most of

them go naked and are covered with all kinds of repugnatlt

coetaneous eruptions. JJ

In 19 3, the first official c nsus conducted by the American authorities

recorded the existence of "Negrito groups" in Sibuyan. They were

probably referring t o the Mangy n Tagabukid, and t he misleading

identification was due to their method of classifi cation by perceived color

of t he skin or raCial type.

Although some of the information was found to be false, the existence

of the M ngyan Tagabukid in Sibuyan has always een acknowledged.

This was again reinforced in Beyer'S 1916 publication The Population

of the Philippine Islands wherein he listed 43 "recognized ethn graphic

groups ', incl udi ng the Mangyan in Sibuyan, Romblon and Tabla.

As of 1994, the indigenous population on Sibuyan is estimated at 1,557.

Their hinterland villages are located in the towns of Cajidiocan and San

Fernando with a population of 1,846, comprisi ng 335 households.

Their survival throughout the centuries, through colonizations and

incursions, affords us a closer look at a people so little-known.

Perhaps because of its geographical barriers, Sibuyan Island is far off

busy trade routes and is hardJy a popular destination. To compound their

isolation, the ancestral domain of the Mangyan Tagabukid lies along the

interior slopes and spine of the mountain range traversing eastern Sibuyan.

This seclusion has brought about a distinct, indigenous way of li fe.

Settlement Patterns and Housing

Because of their close relationship with their environment, natural

features of tile terrain such as streams; waterfalls, rock formations and

caves serve as markers for their ancestral ground. Other distinct settings,

such as tradirionaJ sacred grounds or burial sites, are also used. Most

of their settl ement areas are named after these landmarks, using terms

originating from their ancestors.

Many of the houses within a community are far apart or follow

a dispersed pattern.

A typical house is a bungalow-type structure, elevated about a foot

above the ground. The building materials come from the forest and their

respective tati (fallow land). Roofs are thatched, while walls are of cogan

or wood, with no partitions. The fl oors are made of bamboo. Instead

of nails, uway (rattan) is used. Hard wood like mangatsapoy, bitis and

kauahinan are used as posts.

There is usually only one room, which serves as living quarters, di ning,

and receiving room. At the center is a sahing (cooki ng area), which is

considered the most important part of the house. Members of the household

sleep in the areas around [he sahing.

There is generally only one family per house. Households are nuclear

in nature, with siblings living near each other or near their parents' house.

At rimes, they also build a ku-ob, a temporary shelter when hunting

and gatheri ng in the forest. The ku-ob is a single-pitched lean-to with

no walls and no flooring. It can withstand strong winds and rains.

h uses the leaves of saiirang, tibangyan or pakoy for roofing.

Below, traditional house made of

forest materials; right, a nuclear

fami ly posing oll:tside their hcmse

Another type of a Mangyan Tagabukid traditional house is the timuso.

The tent-like structure usualJy has a large fern roof and support posts

made of local timber called kasaw.

Language

Today, the Mangyan Tagabukid speak a language generally similar to

that spoken in the lowlands. The village elders still remember how previous

generations spoke differently, with a distinct tone. The change may be

due to greater exposure to t he lowland society in more recent times.

Researchers from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) regard the

present language as a variant of Romblomanon. It is further claimed that

the Sibuyan islanders' clialect shares 70% intelligibility with Aklanon,

70% with Tagalog, 73% with Hiligaynon, and 94% with Romblomanon.

This shows a relatively close relationship with the nearby islands and

may be attributed to their coasrallife after their conversion to Christianity

during the Spanish colonial period.

Garb

In the early times, both men and women use birang (bark cloth) to

cover their private parts. The bark cloth was stripped from the trunks of

local soft wood like ginawwag. alrnacigo. santik, nardong and duayong.

Sometimes, the men would use anabo (loincloth). Single women wore

an alimpay (upper garment ) along with the birang.

When they were converted to Christianity, these g.arments gradually

went out of fashion. The Mangyan Tagabukid refer to this period as

"nang nagkamalisya na" (when malice set in). However, some elders

remember that they continued to wear the traditional clothing until the

end of World War n to as late as the 1960s.

Most of the Mangyan Tagabukid today wear no ornaments. Neither

do they practice tattooing or body piercing, which de Goiti observed

among them in the 16th century and which is still common to other

indigenous groups.

Every Mangyan Tagabukid owns a suntUlng (bolo). The phrase "never

leave home without it" is very much applicable to the sundang. Men tie

it around their waist whenever they go to the urna (swidden fields) or

iiawod (town) . Both men and women use it in farming, collecting forest

products, or catcning shrimps. Uway (rattan) baskets of all shapes and

sizes are used as containers.

Social Organization

Today, various factors affect the Mangyan Tagabukid"s mobility and choice

of residence. These are marriage, children's education and source of income.

Males are usually circumcised at the age of seven. Upon reaching the

age of 10, they are expected to help with chores like fetching water or

assisting in the farm. A young boy is considered of age, an ulitawo or

soltero, when he starts courting. They also r fer to this as nagasupang.

a stage when a young man would start associating with a young woman.

As early as the age of seven, females are taught house chores. They

are expected to run errands for their parents and help take care of their

younger si blings. A young woman is considered of age when she develops

breasts, and upon the onset of menarche. This usually happens when a

Mangyan Tagabukid woman is 15 years old.

The Mangyan Tagabukid practice arranged marr iages, initiated by

parents at birth. The potential spouse usually comes from another kin

of affinity, which strengthens ties between inrermarrying kin. Today,

an inclividual may choose whom he or she wants [0 marry, although some

kin groups have mainrained ties based on generations of intermarriages.

Marriage to a taga-ubos has also been prevalent in recent years. Mansibado.

an arrangement in which a man and a woman decide to live together prior

to marriage, is observed in most of the communities.

Even in cases of arranged marriages, courtship is perform d. In the

traditional courtship practice, both the suitor and his parents visit the

girl's parents to signify the intention of t.be male for marriage in the pabagt;

or pasaka baba. After this, the suitor is expected to render bride service,

or pangagad. In some cases, the swtor lives with the girl's family to render

such service. This can progress to the kasayuran in which the girl's family

decides whether to accept or reject the marriage proposal.

Nowadays, bride service is not strictly observed. The kasayuran is

immediately entered into and the date of marriage is set. There are instances

when, after the kasayuran is done, the parents immediately hand the girl

over to her new family.

) ()ckwis(! (/"(Jill lop lell:

Mf. Glilin

o

$utillg R<1Il$c;

CTlltlllg<1S Rll'er, Br,lhmlllY

Kite: abaca plallt; rattail;

AIlLestTal Dnmam map

(shaded areas): thick forest

TH ELAN DSCAPE

The island is some 350 kilometers south

of Manila and situated at 12" 14' and 12"

30' latitude, 122

0

25' and 122

0

42'

longtitude. It is bounded by Romblon

Island in the northwest; Tablas Island

on the west; Masbate on the east; and

Panay Island on .the south.

The ancestral domain of the Sibuyan

Mangyan Tagabukid is located

approximately between 12 17' 57" and

12 27' IS" north and 122" 34' 43" and

122

0

40'13" east and occupies an area

of about S,ooo hectares in the eastern

portion of Sibuyan. Its boundaries adjoin

the municipalities of Cajidiocan and San

Fernando.

The range lies from north to south and

is dissected by a river systems. One of

the rivers, the Cantingas, separates the

eastern portion of the domain from the

central range of Guiting-guiting and the

smaller portion of the claim in the west.

The northern parts of the domain are

undulating to moderately sloping in

contrast to the rugged topography and

higher elevations of the southern half.

Access to the upland communities in the

north is easier due to the existence of

paved roads halfway into the interior.

On the other hand, entry to the southern

interior communities generally starts

with a short hike on level ground

followed by a lengthy ascent as slopes

originate closer to the coast.

Residency after marriage IS by and large virilocal,

as shown visibly by the presence of dist inct kin group

in particular settlements. land availahil ity als affects

setrlemenr arra ngemenrs. Intermarrying ki n groups

consider t hemselves a collect ive set rlement belongi ng

to single territory. This is reinforced by t h bi lat er I

system of ki n recognized in all [he communi ties.

Leadership and Conflict Management

Tradi tional leaders are rhe authori ry

concerning t he welfare of the entire

community. These traditional leaders ar e t he

managhusay, prominent male elders from

va rious kIn groups in their respe rive

senl ement clusters. The elders' main tasks

concern set Llement of conflicts and t he:

maintenance of harmonious relations among

vari ous kingroups, and wit h neighboring

sitio5. Confli cts are settled in a process called

ergohan (verbal agreement ), which concludes when (he offender asks the

offended parry for forgiveness. If both parties are at fa ult, each of them

is asked to forgive and forget t he incident.

Family conflicrs are resolved by the family alone. It is very seldom that

a family confl ict becomes the concern of the community. The parents or

grandparents act as mal1aghusay.

In the 1990s, the osce introduced t he concept of having tribal

chieftains. The local justice system has also incorporated the Mangyan

Tagabukid under its jur isdiCtion, limiting the type of confli cts that t hey

can setrle on their own.

Subsistence Strategies

Like other indigenous peoples, the Mangyan Tagabukid have a full regard

for the symbiotic relationshi p of t heir land and life. When referring to lands,

they not only refer to t heir kaingin or uma (swidden fields) but also to their

settlement area, their lands near a water system or those used for vegetable

gardens (for crops like squash and sayote), fallow land (iati), and the forests.

Every Mangyan Tagabukid household has its own uma; claim to t he uma

is based on usurrucr. Owned lands refer [Q (he serrlemem areas and farm

lots, while forest wlri"til1 the area is considered common property.

Tubers such as bali"ghoy (cassava), kamote (sweet potato), gabi (taro),

and hllndo (yam) are their staples. Rice and corn are Iso planted, as are

some fruit trees li ke banana and pomelo. Corn is planted in May to July,

and rice in June to November. Sometimes they wait for the corn harvest

before plaming rice. Tubers are planted in November to April . lnter-cropping

and overlapping o f cycles of di fferent cr ps are practiced to secure

household food supply. Fallow lands arc uttl ized as gardens and are sources

of luway (tiger grass). Whil e produce from the fields is generally for home

consumprion, gabl and bl/.ndo are regularly sold to the town for cash

[Q buy salt, cooki ng oil , kerosene and matches.

Tradit ional ri ce varieties planted include the tapuy (red grain) , lubang

(brown rice), pulahirz (red rice), panda/i, Santo Nino, batukan, and guis.

The highest yield is of pandmt , as it is t he most resistant to pests and

birds with its sharp leaves and hard gra in hull.

Although their uma is the prunary source of dai.!y sustenance, they

practice multiple subsistence strategies. Banana and seasonal fruits are

also sold to a ugment household income. Nito-ga thering and nire pl ate-

making are alternative sources of income for some famil ies . Women

are generally respon ible for marketi ng these produce.

Dugos (honey) is another major source of income deri ved fro m t he

forest . It brings in the most money to a nWl1 ber of Mangyan Taga bukid

fami lies. In L a ~ r a g alone, some 22 households engage in honey-gathering.

It is usuall y done by the men because it r qui res strengt h and stamina.

The usual method is to drive away bees with smoke from fire. Gatherers

prefer to ser out in pairs, with an understanding that t he collection will

e split equally. T hIS is especi all y profi table duri ng the dry months, when

fl owers are in full bloom.

Rivers and streams are sources of ulang, or freshwater shrimp. Unlike

some of the lowlanders who use cymbus, a chemical use as a spray for

bana na plants, the Mangyan Tagabukid prefer [0 use tao11, a net made

from vines . They know the harm cymbus does to the water system as it

kllls even me small fis h.

The forest within t he Mangyan Tagabukid domai n provides ample

grounds for pangayam (hunt ing). Traditional hunt ing techni que involve

stalking wild animals with the use of bangkaw (spearl, subdui ng them

phy ically, or using snares and pit traps.

E.lch settlement cl uster has its own bunting zone. Hunters from another

serrlement are permitted to operate within the forest area of an adjacent

settlement. However, the settlement 's authoriry over its territory is respected.

Chance encounters of hunters from twO different territories end in verbal

agreements to esta blish boundaries.

TI1e generall y sustai na ble traditional swidden agriculture of earl ier rimes

is slowly bing rendered obsolete. Their area of mobil ity has been

constricted due to increasing population pressure and access restriction

imposed by forestry laws. This has made them resort to the more intensi ve

slash and burn method, which is destructi ve to both soi l and forest cover.

When loggi ng was banned, some men resorted to searching the forest

for narra roots to dig up. These are the remains t hat loggers leave behind

afte r felling a tree wit h a cl'lainsaw.

Clocklllise, from top, b.tll$kaw; g ~ b i plant;

taDn tor cat chtng ultmg

Many, however, have to sell t neu- labor for wages, at times to illegal

loggers who engage in t imber poaching. Since renting a chainsaw is very

expensive, axes are used. This met hod substantially lengthens rhe rime

and effort needed t o cut up the wood. The preferre measurement is

disisais, or 16 inches in di ameter. The poachers sometimes haul t hese

down, ai ded by a cara bao. They get PSO fo r every piece of disisais,

or PIOO for two days' work.

Furniture makers buy most of this wood, and this is still a thriving

business in Sibuyan. This results'i n the continui ng denudation of the

Si buyan forests.

Land Ownership

The person who clears the land for kaingin acquires entitlement to the

land. However, sharing it with another Mangyan Tagabukid is also possible

if th family does not use the land and permission is requested. This rarely

happens though, as each family opens land for their excl usive use. Renting

is rarely an option, because anyone can use another's land without the

owner expecting payment.

Ownership of land is transferred to children through verbal agreements

and is not supported by any written documents. The community respects

this agreement by not occupying any lot (whether for farmi ng or settlement)

that another person or family has been occupying for several years. Even

if the owner bas left the place, the community will still consider the place

his or his fa mi ly' S property.

The transfer of ownership from parents to children wit[ not happen

while the parents are stiJ[ ali ve and sti ll capable of till ing the farm. If the

land is big enough, a portion of it wi ll be given to a newl y married son

or daughter. Otherwise, the famil y and the new couple share whatever

they have or open a new swidden.

Organization of Labor

Family labor is required in developing and cultivating tbe swidden

fields . Traditional gender-specific roles are observed: men are mainly

responsi bl e for earning a living, while women are in charge of domestic

The t rifle U$I!S age- old tedmiqlles tn carr)' w(; od /!()"rds through the

motmlams. F.IJen the yowtgst childrell carl do it.

responsibili t ies. The mother runs most of domestic chores such as cooking,

taki ng care of the children, washing t he cl othes and cleaning the house.

The father performs physically demandjng work in t he farm such as

fi eld preparation, h::trvesting of coco uts and wood extraction.

Children are expected to belp out both in the house and in the field

at an earl y age. The whole family parricipates in household and farm

work, from planting to h:J.rvesti.ng to selling.

Some Ma ngyan Tagabukid are tenants or caretakers of other's lands.

The systems of product-sharing are called dose-dose, ti71u/o and imtpat .

In dose-dose, for every 6 cavans of harvest. one wil l go to he la ndlord

and me rest will go to t he tenant. In this arrangement, the seeds are

provided by the tenant . [n the Imulo, one-third of the yiel d will go to (he

landlord while two-thirds will go to the tenant. The tenant shoulders

the cost of the seeds. Three parts of the yield will go to the tenant in

inllpat while a part goes to the landlord. The tenam provides seeds. After

harvesting pala)' or om, he is entirled to all the produce.

The landlord ca n al 0 assign the tenant to pla nt other crops, such

as coconuts, in his land. However, if the tenant wishes to plant tubers

or mher crops within the coconut plantation, the tenant is not obligated

to share t h raps wi th the landl or d. It is assumed tha t the main

responsibi lity of the: tenant, in this aspect, is to take care of the coconut

plantati on and guard it from thieves.

Beliefs and Practices

Despite conversion to Christianity, the Mangyan Tagabukid still adhere

to some of their traditional beliefs and practices.

Spirits

They believe that benevolent and malevolent nature spirits intluence the

well ness of life and circumstances of a person. Appeasement of the spirits

and ensur ing good life is guaranteed by consulting the spirits and perfonning

riuals with t he aid of a manugbuyong, or a shaman.

Malevolent spirits are generally called tao sa duyom. These incl ude

ku/ipaw, maligno, sigben, duwende, kapre, bulalakaw or diwata, engkanto,

and the angkag. The angkag is a human-like creature with animal features

and resides in caves. The bulalakaw is a living creature carried by a ball

of fire. To protect themselves from the harmful bulalakaw and drive away

bad luck, the natives wear pailas, a native necklace or bracelet.

These spirits are believed to inhabit the forests. An individual who

accidentally trespasses on their territory may be harmed. The spirits

can only be warded off by a shaman's offering or prayers.

Another spirit believed to be dwelling in forests is the mangon, which

is described to have a head shape:d like a bag. It is said to show itself to young

men and make incomprehensible sounds. Gatherers of nita and rattan

quickly leave the forest as soon as they feel the presence of the mangon.

Health Practices

The Mangyan Tagabukid believe that natural and supernatural forces

cause il lness . The most common illnesses tbey suffer from are fever,

influenza, cough and colds, di arrhea, stomach aches and gas pains,

gastroenteritis, rheumatism and mi nor respiratory disorders.

Herbal medici ne is a popular remedy. While some famil ies simply

require the sick (0 stay at home and rest, others take the sick to the

local health center or the shaman.

The shaman makes a diagnosis by feeling the patient 'S pulse. They

believe that a person who has been enchanted has a rapid pulse beat.

When it has been determined thar the illness was caused by spirits,

an offering of tuba or rice is made. The healer will also burn incense

and smoke tobacco to

produce smoke that

will envelop the sick

person. The process

signifies the

redemption of the

person's soul from the

spirits.

Ottgyo is an illness

ca used by immersing

in the river wben a

person's body is not

prepared for rhe cold

water. This is

characterized by

prolonged itchiness

and rashes. The cure

consists of a ritual

wherein the rashes are

Manugbulollg (shaman) performi11g a ritual to cure o n ~ ; y o

struck with human hair seven times and coconut oil is appU d to the

afflicted parts. A prayer is also recited to appease the spirits.

There are also many beliefs regarding childbirth. To facilitate [he

process, the mother 'S stomach is rubbed with a ladle seven t imes . The

farher or any family member must also sweep outside the h use, near

the door. After giving birth, the woman is not allowed [0 rake a bam mit

the 11th day because her veins are believed to be open. Bathing at this

time might get her sick.

Farming Rituals

The Mangyan Tagabukid still practice rituals that signify care for the

land an d ommuning wim nat ure. Pami1thi, a ritual before planti ng rice,

involves chant ing of prayers and giving offerings to (he spirits for a

prosperous yield. A prayer signals rhe start of t he activity. Stones and

water are set in a coconut shell and placed on tOp of three.pieces of mi n

wood inside the ri ce field. Offer ings of cooked rice, boiled eggs and tltba

(alcohol) are laid on the ground. Incense is burned; the smoke that spreads

over the area is believed to drive away bad spir its. Bringing water in the

fields during the rit ual is not all owed.

There are also certain taboos during planti ng and harvest. Menstruating

women are not all owed in the field during the plant ing because it is

believed that t heif presence will ca use the wi lt ing of th e crops, as they

associate t he color of blood wi th the color of withered rice stalks. It is

also not advisable to plant during high tide, for it will not resul t in a good

yiel d. Harvesters are prohibited from speaking of or bri ngi ng "slippery"

ani mals like tbe freshwater eel and snake.

Dur ing the harvest season, a t hanksgivi ng ri tual is performed for a

bo untiful yield and to protect future crops from insect attacks. Ginger

is placed in the hZ.lmayan or rice container to ward off malevolent spi rits.

The manugtugna, or the ritual performer prays at t he enter of the field

whi le fa hioning a cross Out of twigs or banana leaves. Three white stones

are also laid in a coconut shell, each of the stone taken from an eddy and

along the trail. They believe t hat if stones are coll ected from these places,

yi elds will be abUi dam and continuous. Tlm:e stal ks of nee are tied

together forming a triangle and t ied to a tree SLUmp withm the field. A

piece of bl ack cl oth the size of a matchbox is attached to the cross using

resin. The rocks, toget her with shells, are placed underneath the stalks.

Seven pieces of rice grai ns are collected and placed on me cross, while a

prayer is uttered for each grain. The cross is roll ed in the cloth and buried

in the ground.

From top: Pamill hf, a farmmg ritual

Then, rhe manugtugna will go home and put the grains on top of the

roof, [Q symbolize roof-high, abundant yield. The seeds from the rhree

stalks will be stored for use during [he next planting season.

Harvest begins a day or a after the ritual.

Similar practices are observed in the planting and harvesting of tubers.

In a ri tual called hungod, rice, tuba, coconut leaves an eggs are placed

in the planting area as offerings fo r the pirits . Planting is done only

during low tide because it is believed that the crops will die if planted

duri ng high t ide.

Clockwise from left: Gobi for

transport to the lowland market;

a drink of tuba after planting;

harvesting Ilphmd rice

Tn spite of efforts ro preserve [heir way of life, t he Mnngyan Tagabukid

3re now faci ng pressures from different sectors of society.

Since land tenure arrangements in these commUniti(!s range Fr om us\Lfrucr

to tenancy, it is not su rprising that they do n0t hold document

ownership of the land they ril! or where their home' are buil t. FU'St () t all, their

concept of land is clearl y of property that is simply handed down and owned

over time, hence the term ancesu'al domain. Secondly, their lack of education

prevents them from accessing leg::l l recou l' $es to ensure their tenure of the

land. Although there is no aPPjrent conflict over land tenure at present,

the landholdings J re owned by a few, who are ei rher the more affl uent

lowlanders or are absentee land lords. The Sibuya n Mangyan Tagabukid

are to pl ant for t heir ,uiJs isrencc under sha r ing arra ngcment ,

Li ke most upland commun ities, they do not ho\"e casy access to

services and educ:t cion due t phy iced distance from health ' enters aud

schools and the lack of economic resource to m::lkc acLCSS possible. Ch ildren

\Vho attend school evenruall y :.Ht fro m continuing dL1 e to the

Jnd t he need for money, For al lowance school supplies.

\VhilL rh is tnJigCJ10US popul ati on has cbJ ll ged little in numbe r, and the

LHllling rinu ls and way of life are still rerlective of thci r all cestors' mode

(1f living, one dra tic che nge has come as a tbreat to their ubsistence farming

- 'lI1d their surVival. TIleir <\l lI.:estral domain and tradi ti onal ut ilization of forest

['e::iourccs around Mr. Guiri ng-guiting have been constricted to the poi nt

of depri vation.

The pressure upon their ha bi t:1t-lon and livelihood arises from the fact

that mos t of this mountai n has been declared as a Natural Park in

1992, chosen because of the area 's biodiversity. Although Republ ic Act

7586, otherwise ca ll ed the NIPAS ( arional Integrated Protected Ar as

System) Act, !'ecognizes peoples' in protected areas, the

law is premised on rhe legal fiction of the conquistadors ' Regali an doctrine.

Based on this doctrine, the Spani 'h king owncd the cnrire colonial domain,

except those land parcels duly tirle.d to individuale; and rel iglom .

This doctrine inevitably violated the inherent light of the indigenous

peoples to their ancestral domain and heritage. onethe css, tht.: Philippine

government has redefined the former colonial domain as own nati onal

dommJl or patrimony, similarly ignoring tlte indigenou people" birthright

3nJ threarening the VIabil ity of their way of life.

Furt her source of tension Ir es in the difference of interpretation of the

bw and failure of the various government insritutions like rhe Department

of Environment and Natural RCSfJu n:.cs (DENR) and the National Commission

on Indigenous People (NCIP) to wor k rogerher in resolving issues on the

harmonizarion of ia'A , conservarion IndigenoLls pe )ples nghts, primaril y

in managing areas wbere then,; are ()ver laps of parks and ancc tral terri tories .

Added to this is the uneven repre ellCdtion of indigenoll s communities in the

ma nage ment board Wh( 1Se i. conn'olled by lowlanders J nd the

DENR, and where community prOLe ses and participation are stil l wanting.

Aggravat ing the situation is the series of land use policies of the government

t har run counter co uch indi gen l US subsisrence patterns a slash and

burn agriculture and tracht ional gathering of vines, honey, fuel wood

and hous lI1g materials from rhe torest.

the'e upland vr\ia'iers do nor h:.1Ve exclusive access to forest

rr oduLc extract ion. owla ndcr, Ill OStly migrant to Sibuyan () !" r11cir

descendants, have been poachi ng ti mber fl"Om the range. The .Mangyan

Taga buk id observe the'e lowlanders ro be reckless in thei . extracti on

of fo rest resources because t heir' VvJ)' of li Ce docs not hinge mai nly

on the GO lU1 ry of the range and str.eam "

Left , tlcestrJ! domai ll map

,h(m'ing overT.lppiflg arcas with

\[t. Cllitmu'guiting Natl/ral Park;

Totl . rntr,lJlCC to PAG Offi cr::

ClUSTER IPAREA HH Indiv GENDER

F M

GINTAK-AN 24 155 71 84

LAYAG 66 331 155 176

Buyabog 11 63 31 32

Layag 18 87 48 39

Malapipi 14 56 25 31

Paima 15 84 32 52

Tagbu g 81 41 19 22

KABUYLANAN 56 318 149 169

Ka huylanan 23 117 52 65

Kamagong 8 52 26 26

Dl1WO 10 44 19 25

DUYJ nan 1 13 6 7

Lamao 14 92 46 46

HAGIMIT 84

4W'l

./,) 237 256

Kawa-kawa .3 20 9 ] 1

Da lit 5 28 15 13

Gio ;lhn J2 198 106 92

Hagirn ir 33 186 76 110

Sabla v;] ll 4 26 13 13

Sandig Puya 7 35 t 8 17

PANAGINTINGAN &0 390 18 , 206

Ba!av Lambao 2 6 4 2

6 20 9 11

Gi nakm

24 14 10

.)

Panaginnngan 3 39 20 19

Pinamakahan 2 9 4 5

Pmuka nan 3 16 9 7

Salugon 12 66 33

., .,

.) J

Sinapawan 6 l tl 8 10

Tagaha I 7 5 2

Tagu:ll1 14 7

26 41

TaguJroJ Kalah;!\\' 4 26 15 11

'Yanguh 19 92 37 55

TOTAL 1 /5 1687 796 991

BI BLIOGRAPHY

A. Documents

Distrito de Rombl on: Ano de 1891: Memo ria desm pt ivl dd mis mo redacrada en

vi rtud de la respetable circular del Gobiemo General de esras yslas de 22 de :-.JQ\icrnbre

de 1887

1880: promovido par e1 comanda.me polnico-milita r de Romblon sobrt::

que se Ie contieran arr ibuciones d luez lego

Direcci on General de Adminj st raci on Civil : Num. S: Centro de Estadisrica : rrovinci

de Romblon: Ano de 1896: Pueblo de Azagra: st ado ur bano-agr icola-comcrcial de

eSte pueblo durante el expre 'ado ano

Direcc.ion General de Administr acion Civi l: Num. 1: Cencr o de Estadisrica : Provincia

de Romblon: Ana de 1896: Pue blo de Azagra: Es rado del numero de habitantes

existentes en este pueblo dura nte cl expresado anO cun exprt: ' ion de t ala.

Direccion Gener al de Admini stracion Civi l: Num. 5: entro de Estadistica: Provincia

de Romblon: Ano de 1896: Pueblo de Caji dio an : Estado

de este pueblo durante el expresado ana.

Direccion General de Administraci on ivil: N Unl . 1: ,enrru de Estadi stica : Provinc ia

de Romblon: Ano de 1896: Pueblo de CajidioC:Hl : Estado del numero de habiranrcs

exi stentes en este pueblo durante el expresado ano con c.' presion de ra7. s.

Direccion General de Admin istraci on Civil : N um. 5: Centro de Es tadisti ca : PW\' incia

de Romblon: Ano de 1896: Pueblo de Magallanes: Estado u.r bano- agricola-cornercial

de este pueblo durante el cxpresado ano.

Direccion General de Admini st racion Civil: Num. 5: Cent ro de EstadisticJ : Proyincia

de Romblon: Ano de 1896; Pueblo de Maga ll anes: Estaci o del m mew de habitanres

existentes en cste pueblo durante el e.xpresado am) con exprt: sion de

Provincia de Romblon: Fundacion de Espana en In ys la de Sibuyan: abezeri:l de Don

Ylodio Aribalo

Provincia de Romblon: Fun dacion dt Magall anes en la ys h de Sibuyan: Cabezcr ia de:

Don Bemabe Ri bot

Provincia de Rombl on: Fundacion de Princesa en la ysla de Sibuyan: Cabczeria de

Don Ylario J uan de la Cruz

Provincia de Romblon: Fundaci on de Ysabel en la ysla de Sibuyan: Cabcceri a de Don

Domi ngo de Alexo

1854: Rombl on: Corte de Maderas

Romblon: 1854: Perclidas y arri b das de buques en las costas de Romblon

Romblon: Superi or Go bierno de las islas Fi lipinas: 1854: No_ 5029: Sobre comercio

interi or : Oficio de comandanre mili tar v poli tico de Romblon remi riendo

un comrato de los preci os a que: se han de vender los arti culos que sc Jcopia n cn los

pueblos de Espana, Ysabel y Pri ncesa por las razones que csprcsa

Distrito judicial de Capiz: Num, 3: Provinc..ia de Romblon: Estado por pueblos que

deter mina la extension superficial que comprende el disrriro /udici(l ! de Romblon,

distancia de In cabecera , a la capi tal de ]a provi nci a y a Ia de archipielago, medlo

de ,omlIDica,ion con lIDO y otr o, tiempo qUl: ordi n.Miamenrt se emplca, numcro dt

habi tantes clasifi cados en europcQs e indigen s razas de estos y dialecros qut: hablan

Phil ippineNati ord Library. Historical Data Papers, Province of Romblon.

B. Books

Anthropology Warch

2000 Sl buvan Mangyan Ancestral Domain Census (July 2000). Ms.

1999a Sibuyan M:1ngya.n Tagabub d Customa ry Laws. Ms.

1999b Sibupn Mangyan Tagabubd SWldden Practtces. Ms.

Archives of San Agustin Order Reco!lecrs. .. .

1925 Sino psi s Historia de la ProVLnCl3 de S. NIColas de Tolennno de las Islas

FiLipin as, voll. Order de Agustmo Recoletos.

Beyer, H. O.

1949 Out line Revi ew of Philippine Archaeol ogy by Islands and Provi nces.

BUTeau of Pri nti ng. Manila.

1921 The NOll -Christiall People of the Philippines. Bureau of Printing. Manil a.

1918 [' ofmiati on of the Philippine Island in 1916. Philippine Education. Manila.

Heyer, H. O. and de Vel' ra, Jaime C.

1952 PhilIppi>,,' Saga: A Piaorial History of the Archipelago Since Time Began.

Capitol Publi shing House. Manila.

Blair, Emma Helen and Robertson, James AlexandeL

1973 The Philippine Islall ds: 1493-1898. Cacho Hermanos Inc. Manila.

Blumentritr, Ferdi nand.

1980 A'I Attempt at Writing A Philippine Ethnography. Translated by Marcelino

N. Maceda. Universit y Reseach Cent er (MSU) . Mar awi Ciry.

19 1.6 Tribes and Lan(' uages, in Aust in Craig and Conrado Benitez,

PhililJpille Progress Prior to 1898 (Vol. J). Philippine Education Co., fnc.

Man il a.

1901 List of Natwc Tri hes of the Philippines and of the Languages 5po.l:el1

uy Them. Govanment Printing Office .

Boierin Ed eslastica de

J 965 Bo letin Ecl csiast ica de Filipinas vol.32, no.435. UST Press. Mani la .

Casri llo, Demetr io.

1973 Soil Sur : cy of Rombl on Prov ince. Goveernment Printing Office. Manila.

Conkl in, Ha rold C.

1963

1957

"The Swdy of Shift ing CultivJt ion." Union Panamcri cana. Washington,

D.C.

"Hanunno Agriculture: A Report on an Integral System of Shi ft ing

Cul ti vat ion In rhe Phi lippines. " Fo d and Agricult ure Organ ization

01 the United Nation. Rome.

1954 "The Relation of Hanunuo Culn JI'e to au: Plant Worl d. " Ph. D. DIs.ert;.) tion

(Microfil ms). Ya le Universi ty, University International . Michigan, Ann Arbor.

de la Cavada Mendez de Vigo

1876 Agusrin. Historia Geografiw. Geologica y Esttldistrca de Filipinas.

T01/l0 2: Visayas y Mmdanao, Imp. de Rami.rez y Gi.raudi er, Mani la.

de Tavera, Pardo

19 1 Etim% glQ de Ius Nombres de Razas de Filipillas . M: ni la.

Fox, Robe rt and Elizabeth Flory.

1974 A Map of the Filipino People. Nati onal Museum of the Philippines.

Manila.

Grimes, Ba rbara F., cd

1996 Ethnologtte, 13th Editi on, Summer Insti tute of Linguistics, Inc ..

Heaney, Lawrence R. and Regalado, Jacinto, Jr. c.

1998 Vanishing Treasures of the Philippi ne Rain Forest. The Field Museum.

Chicago.

Ingle, Ni na R. et al.

1994 Mt. Glliti ng-guiting: Establishing a Protected rea wi th People Participation.

Evel io B. Javier FOLlndarion, Inc. Quezon City.

Lebar, EM., cd.

1975 Ethnic groll ps of Insular Southeast Asia. Vol. 2 : Phil ippines and Formosa.

HRAF New Haven.

MA CAJSA

1979 Integrated Area Deuelopmellt Nan: Municipalities of San Fernando,

Cajidiocan, Magdiwang. Sibuya n.

Majni , Cesar Adib

1999 Muslims in the Philippines. UP Press. Quezon City

National Integrated Protected Area Programme (NIPAP)

1999 Baseli ne Survey in Mt. Gui ting-guiting Natural Park, Sibuyan, Romblon

(janua ry 1997).

1997a Draft General Management Pl an for Me. Guiting-guiting Nat ural Park,

October 1997-Dccernber 2002. Manila.

1997b Socia-Economic and Cul tural Profile of the Island of Sibuyan, Romblon. Ms.

National Stat istics Office.

1996 Provincial Profile; Romblon. Manil a.

1995 Census of Agriculture 1991: Ramblon. Manila.

Ol ofson, H., ed.

198 1 Adaptative strategies and change i ~ t Philippine swiddell based societies.

Forest Resea rch Institute. Laguna.

Padilla, Sabino, Jr. G.

1997 Mr. Guiting-guiti ng Project Socioeconomic Report. WWF-Phi lippincs. Ms

1992 "Notes on the Agri clllrural System of the Mangyan Patag," Interna ti onal

Works.hop on Local Knowledge and Global Reoources: Involvi ng Users

in Germplasm Conservati on and Evaluation, Users Perspective wi th

Agricultural Research a nd Development (UPWARD) and Interiati onal

Devel opnem and Research Center (IDRC) , 4-8 May 1992.

Padi lla, Sabi no, Jr. G. and Gui a, Ma. Teresa B.

1991 "Development Wor k and the Indigenous Peopl es, " KABALIKAT:

The Development Worker. June 1991. pp. 1, 3-5.

PaguntaJan, Aileen May et ai.

1998 The Tagabukid of Sibuyan. AnthroWatch. Quezon Ciry. Ms.

PANl.IPI

1997 A Studv on the Life and Aspi rations of Taga buki d, the Indi genous People

in Sibuyan Island, Provin eo Rombl on. Quezon City.

Russel, Susan D.

1986 Mountain People in the PhiliPeines: Ethnographic Contribution in Philippine

Upland Communities. In S. FUJisaka et aI. , Man, Agriculture and the

Tropical Forest. Winrock International Institute for agricultural

Development. Bangkok.

The Phili ppi ne Commission

1901 Report of the Philippine Commission to the President, Vol. III. Government

Printing Office. Washington.

Torres, Meliza Joy A.

1997 NlPAP Cultural Profile of the Mangyan Tagabuk id of Si buyan Island.

Draft Report .

Warren, James Francis

1985 The Sulu Zone 1768-1898. New Day Publishers. Quezon Ciry.

C. Interviews

Diego, Proseso SL Key Informant. Kabuylanan, Si buyan Island, Romblon. October

1998.

Recto, Bonifacia. Key Informant. Salugon, Sibuyan Island, Romblon. October 1998.

Regia, Epifani o. Key Informant. Panagintingan, Sibuya n Island, Romblon. October

1998.

Ruba, Henerosa. Key Infor mant. Hagimit, Sibuyan Island, Romblon, October 1998.

Tolentino, Jose. Key Informant . Pa-ima, Sibuyan Isl and, Romblon. October 1998.

PHOTO CREDITS:

WWF-Phili ppincs

Dr. Sabino Padilla, Jr.

AnthroWatch

PAFID for the maps

Ivan Sarenas

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- HistoryDokument24 SeitenHistoryKey Harken Salcedo CrusperoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Tribes of Buk. BSHM 1b 2semDokument11 Seiten7 Tribes of Buk. BSHM 1b 2semJea Sumaylo HamoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief History of The Town of BulanDokument3 SeitenA Brief History of The Town of BulanmotmagNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACE HymnDokument14 SeitenACE Hymnฟรๅนฃีส เจฃัNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Literature of BesaoDokument16 SeitenThe Literature of BesaoChu RhoveeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SIPALAYDokument3 SeitenSIPALAYjeane annNoch keine Bewertungen

- Region 10Dokument19 SeitenRegion 10glenn canoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of The Schoo1Dokument2 SeitenHistory of The Schoo1Ismael S. Delos ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misamis Oriental HistoryDokument4 SeitenMisamis Oriental HistoryNiña Miles TabañagNoch keine Bewertungen

- ,history of CagayanDokument11 Seiten,history of CagayanJohnny AbadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christianization of The NorthDokument5 SeitenChristianization of The NorthMary Ann Santos100% (1)

- Negros Occcidental History and Culture - Bacolod and Talisay (Autosaved)Dokument63 SeitenNegros Occcidental History and Culture - Bacolod and Talisay (Autosaved)Rafael A. SangradorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Famous LandmarksDokument18 SeitenFamous LandmarksCarodan Mark JosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To MSU System PresidentDokument1 SeiteLetter To MSU System PresidentNorjehanie Ali0% (1)

- Deped HeaderDokument1 SeiteDeped HeaderCarol Nicod-am BelingonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barangay PangpangDokument10 SeitenBarangay PangpangAldrin Ray HuendaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Guman of DumalinaoDokument2 SeitenThe Guman of DumalinaoAngelica Sayman Gomez100% (1)

- The Life and Tradition of BukidnonDokument5 SeitenThe Life and Tradition of BukidnonIsrael Adrigado100% (1)

- BayaniDokument3 SeitenBayanitadashiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subanon: The Subanon People of Living in The Mountains ofDokument2 SeitenSubanon: The Subanon People of Living in The Mountains ofjs cyberzoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Festival Sa Bicol RegionDokument9 SeitenFestival Sa Bicol RegionJec Luceriaga BiraquitNoch keine Bewertungen

- T'boli: Songs, Stories, and SocietyDokument19 SeitenT'boli: Songs, Stories, and SocietyJihan Ashley RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historical Background of CaragaDokument4 SeitenHistorical Background of CaragaLeighgendary CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amador DaguioDokument1 SeiteAmador DaguioCarmella Mae QuidiligNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loboc Travel BrochureDokument2 SeitenLoboc Travel BrochureMike AmbasNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSTP (Flag Heraldic Code of PH) L4Dokument25 SeitenNSTP (Flag Heraldic Code of PH) L4DAIMIE CLAIRE BIANZONNoch keine Bewertungen

- BrochureDokument2 SeitenBrochureCarlo DimarananNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Agusanon ManoboDokument1 SeiteThe Agusanon ManoboMarceliano Monato IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter - Viii - Preactivity - Ical, Erica Ann e PDFDokument5 SeitenChapter - Viii - Preactivity - Ical, Erica Ann e PDFErica Ann IcalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Festivals of TarlacDokument3 SeitenFestivals of TarlacJambi LagonoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Deen BenguetDokument17 SeitenFrom Deen BenguetInnah Agito-RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pangasinan Songs: Oalay Manoc Con TarazDokument1 SeitePangasinan Songs: Oalay Manoc Con TarazPRINTDESK by Dan100% (1)

- Resource 1.3 Instances of Moro Lumad and Christian CooperationDokument4 SeitenResource 1.3 Instances of Moro Lumad and Christian CooperationKobe EmperadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occidental MindoroDokument10 SeitenOccidental MindoroMaureen Joy Aguila GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Awiting Bayan ButuanonDokument16 SeitenAwiting Bayan ButuanonShe TorralbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bubudsil Ethnic Dance: TitleDokument4 SeitenBubudsil Ethnic Dance: TitleJay GamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Legend of CalapiDokument3 SeitenThe Legend of CalapiMA. THELMA B. EBIASNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mt. Hibok HibokDokument5 SeitenMt. Hibok HibokJoanna Marie IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Ati - Atihan FestivalDokument10 SeitenAti - Atihan FestivalAidahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reaction Paper: Nuguid, Wendel SDokument2 SeitenReaction Paper: Nuguid, Wendel SWendel NuguidNoch keine Bewertungen

- PHILIPPINE TOURISM (Western Visayas - Region VI)Dokument29 SeitenPHILIPPINE TOURISM (Western Visayas - Region VI)Crhystal Joy ReginioNoch keine Bewertungen

- TravelogueDokument12 SeitenTravelogueRosa PalconitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hist1 M4 L9 TaxationDokument9 SeitenHist1 M4 L9 TaxationpehikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rizal Memes and Its ReflectionsDokument7 SeitenRizal Memes and Its ReflectionsNicole Mercadejas NialaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts Education 7 ModuleDokument32 SeitenArts Education 7 ModuleShane HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cordillera HymnDokument5 SeitenCordillera HymnMaribethMendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hundred IslandsDokument9 SeitenHundred IslandsJoyce CostesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Don Hard and Harriet Hart-Juan Pusong Filipino Trickster RevisitedDokument34 SeitenDon Hard and Harriet Hart-Juan Pusong Filipino Trickster RevisitedPingkay LagrosasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Spanish: Lesson 2Dokument3 SeitenPre-Spanish: Lesson 2Gayle JavierNoch keine Bewertungen

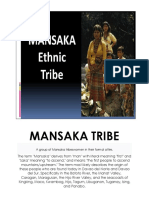

- Mansaka Tribe: A Group of Mansaka Tribeswomen in Their Formal AttireDokument6 SeitenMansaka Tribe: A Group of Mansaka Tribeswomen in Their Formal Attirejs cyberzoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- FuppppDokument9 SeitenFuppppJacinth May Balhinon50% (2)

- Abra MarchDokument1 SeiteAbra MarchLfhsAbraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Informal Reading Inventory - Silent Reading: (Antas NG Bilis Sa Pagbasa) (Antas NG Pang-Unawa)Dokument4 SeitenPhilippine Informal Reading Inventory - Silent Reading: (Antas NG Bilis Sa Pagbasa) (Antas NG Pang-Unawa)bodenz_dvp100% (1)

- History of Balut Island: RationaleDokument17 SeitenHistory of Balut Island: RationaleJessemar Solante Jaron WaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Region 1 (Ilocos Region)Dokument13 SeitenRegion 1 (Ilocos Region)Alvin GacerNoch keine Bewertungen

- ManoboDokument6 SeitenManoboSt. Anthony of Padua100% (1)

- LocalhistoryDokument18 SeitenLocalhistoryKyla AlbanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kankana EyDokument56 SeitenKankana EyRoban Kurispin70% (23)

- Maine Food SummaryDokument6 SeitenMaine Food SummaryAli Shaharyar ShigriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filament Dallas Lunch MenuDokument8 SeitenFilament Dallas Lunch MenuEaterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Current Trend of Tractor Industry PDFDokument8 SeitenCurrent Trend of Tractor Industry PDFHari PeravaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- CanihuaDokument8 SeitenCanihuaEdwin SauñeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Village and Town GeneratorDokument2 SeitenVillage and Town Generatorarclet100% (1)

- Tom Yum RecipeDokument3 SeitenTom Yum Recipeapi-247572990Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 PDFDokument16 SeitenChapter 3 PDFGopinath RamakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cucumber Production GuideDokument12 SeitenCucumber Production GuideLaila UbandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Landscape Plant Salt Tolerance Selection Guide For Recycled Water Irrigation PDFDokument40 SeitenLandscape Plant Salt Tolerance Selection Guide For Recycled Water Irrigation PDFRoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Main Staple Food in The Philippines Is RiceDokument2 SeitenThe Main Staple Food in The Philippines Is RiceErnest ArceosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Requirements of Roses: Design For Everyday LivingDokument2 SeitenCultural Requirements of Roses: Design For Everyday LivingAnonymous loKgurNoch keine Bewertungen

- ElectrocultureDokument7 SeitenElectrocultureefraim75100% (3)

- Periodic Assessment of Waterlogging & Land Degradation in Part of Sharda Sahayak Command Within Sai-Gomti Basin of U.P.Dokument8 SeitenPeriodic Assessment of Waterlogging & Land Degradation in Part of Sharda Sahayak Command Within Sai-Gomti Basin of U.P.SunnyVermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dairy Production - PPT (Compatibility Mode)Dokument9 SeitenDairy Production - PPT (Compatibility Mode)Chan Nhu100% (1)

- Production Guidelines Tomato PDFDokument22 SeitenProduction Guidelines Tomato PDFAgnes Henderson Mwendela100% (2)

- Principles of Erosion ControlDokument14 SeitenPrinciples of Erosion ControlsaurabhNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSS Farm ProjectDokument14 SeitenNSS Farm ProjecthanderajatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mangosteen PDFDokument11 SeitenMangosteen PDFfrankvalle5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Science: Lecture Chapter 7Dokument62 SeitenEnvironmental Science: Lecture Chapter 7gwapak83Noch keine Bewertungen

- Methods of Applying FertilizerDokument27 SeitenMethods of Applying FertilizeramarimohamedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrating Seed Systems For Annual Food CropsDokument329 SeitenIntegrating Seed Systems For Annual Food Cropskiranreddy9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Soal Tbi Baru 2019 (Student)Dokument2 SeitenSoal Tbi Baru 2019 (Student)Manchester cityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iodine Test StarchDokument6 SeitenIodine Test StarchLester PuatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plant - Production BookDokument28 SeitenPlant - Production BookGabriel BotchwayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Almeda Vs Court of Appeals 78 SCRA 194 (1977)Dokument5 SeitenAlmeda Vs Court of Appeals 78 SCRA 194 (1977)Evelyn Bergantinos DMNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gasoline Engine On The Farm 1000032086Dokument561 SeitenThe Gasoline Engine On The Farm 1000032086ecasayang100% (1)

- Caterpillar - Motor Grader Application GuideDokument40 SeitenCaterpillar - Motor Grader Application Guidefvmattos100% (4)

- Eco Agric Uganda Narrative Report For The Firstquarter 2016Dokument11 SeitenEco Agric Uganda Narrative Report For The Firstquarter 2016jnakakandeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mini Combine Harvester-Team AgroDokument24 SeitenMini Combine Harvester-Team AgroavatarsudarsanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 High Efficiency Boiler Technology Sugar Industry Suwat enDokument29 Seiten6 High Efficiency Boiler Technology Sugar Industry Suwat enctomeyNoch keine Bewertungen