Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Gulzad - History of The Delimitation of The Durand Line - 1991 PDF

Hochgeladen von

Cici ShahirOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Gulzad - History of The Delimitation of The Durand Line - 1991 PDF

Hochgeladen von

Cici ShahirCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

THE HISTORY OF THE DELIMITATION OF THE DURAND LINE

AND THE

OF THE AFGHAN STATE (1838-1898)

by

ZALMAY AHMAD GULZAD

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

(History)

at the

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON

1991

by zalmay Gulzad 1991

All Rights Reserved

ii

iii

Dedicated to my family and especially to the memory of my

younger brother Nangalai Jan.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As I draw towards the conclusion of my graduate studies,

I realize of all the people that have contributed towards this

achievement, I am most grateful to Professor Joseph Elder, who

truly surpassed his role as my mentor. Joe was not only a

source of inspiration but encouraged freedom of thought.

Also, he unhesitantly provided solace to me especially during

the most difficult times. I am indebted to Joe for his

invaluable comments on the dissertation and most of all for

his persistent faith in me throughout my graduate studies.

I consider myself fortunate to have known both Joe and Joann

Elder and will always be grateful for their constant support.

I would also like to extend my thanks to Professor Andre

Wink, who was most gracious in accepting to join my committee

at the later stages. Nevertheless, his comments and valuable

criticism truly played an important role towards the

ref inement of this work. I express my utmost thanks to

Professor David Gibbs, whose reassurance and comments were

always readily available. He has truly been of great

assistance in my work. I would also like to acknowledge

Professor Kemal Karpat for his contribution in my studies.

Throughout my graduate career Professor David Knipe has always

been reassuring and receptive of my work. I am most obliged

to Professor Stephen Humphreys for his invaluable guidance

v

during his tenure in Madison. Professor Humphreys' seminars

contributed immensely towards my research and studies.

Finally, Professor Manendra Verma was most effective in my

lanuage training.

lowe a tremendous amount of gratitude to my family for

their continuous support, love and committment in this

endeavor; Especially my brother, Zaffar Gulzad, who

unhesi tantly offered his encouragement and support. My

special thanks to Lata, who has been a true companion

personally and academically. To my comrade and friend Rick

Rozoff, I am most obliged for his insightful suggestions.

without the generous funding of the American Institute of

Indian Studies (AIlS), this study would not have materialized.

I must thank Kaye Hill and Pradeep Mahendirata for all their

help during my AIlS fellowship. I would also like to extend

my gratitude to the Indian Government and the Afghan

Government for allowing me to have access to documents

pertaining to my study. Dr. Ravindra Kumar, the Director at

the Nehru Memorial Library, contributed immensely to my

research in India. I must acknowledge the staff at the

National Archives in India and at the India Office Library and

Public Records Office in London, who were most generous in

their assistance. The staff at the Memorial Library,

especially Judy and Dineen, were most patient and helpful in

the use of the facilities.

vi

Finally, without the guidance of Judy Corchoran and the

aide of the History Department staff, this study would not

have been possible.

Afghanistan's specific historical experience has

contributed towards its current political quagmire. Almost

every family has experienced the loss of a loved one, the

psychological consequences are inexplicable. The colonial

legacy of the region has only intensified the conflict, which

if history must not repeat itself, Afghans everywhere must

work towards uni ty and the restoration of peace in their

country.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 0 0 iv

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0. . . . ~ Q 1

CHAPTER ONE:

CHAPTER TWO:

CHAPTER THREE:

CHAPTER FOUR:

CHAPTER FIVE:

CHAPTER SIX:

CHAPTER SEVEN:

CHAPTER EIGHT:

CHAPTER NINE:

CHAPTER TEN:

The Establishment of Afghanistan

Under the Suddozais e

The First Anglo-Afghan War: The

Rise of the Imperial Frontier

Sner Ali's Internal Reforms Prior

to the Second Anglo-Afghan War

The Second Anglo-Afghan War

23

69

117

(1879-1880) 150

The Origins of RUSsophobia and

Its Impact on Anglo-Russian

Relations in the Nineteenth

century 181

Anglo-Russian Imperial Rivalry in

central Asia 206

The Power Structure and social

Change During the Reign of Amir

Abdur Rahman (1880-1901) 244

The Delimitation of the Russo-

Afghan Boundary e 292

The Drawing of the Durand Line 309

The Durand Line and the Aftermath 348

CONCLUSION. 397

APPENDICES 0................ 406

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHy 424

viii

PAGE

MAPS

Map 1.

..

. . . . .

..

CI . . .

o

22

Map 2.

..

. . . . . . . .

. . .

. .

..

. . . . .

205

Map 3.

-. .

.

. . . . . .

291

Map 4.

. .

. .

. . . . ..

. .

347

- INTRODUCTION -

Afghanistan (modern), Khurasan (medieval), or Aryana

(antiquity) were geographic and cultural expressions that

were used historically by outsiders to denote the area and

its inhabitants.

1

Because of its geographic location,

Afghanistan was subjected to a continuous flow of population

migrations and invaders. In the tenth and ninth centuries,

prior to the development of maritime trade, overland trade

routes across Afghanistan intersected at centers like Kabul,

Peshawar, Balkh, Kandahar, Farah, Ghazni and Herat, forming

a series of market networks.

2

It was along these networks

that dynasties like the Ghaznawids (963-1148) and the

Ghurids (1173-1206) established their power in

Afghanistan.

3

The Ghaznawid military base and more so that

of the Ghurid rested largely on Afghan tribal support.

4

As important partners of the rulers, these Afghan tribes

acquired capital and more importantly land, which in turn

strengthened their position within the country. Under the

Ghaznawid and Ghurid dynasties, various campaigns into India

helped stimulate Afghanistan's economy by bringing capital

and products into the region. Consequently, Afghanistan's

commerce became linked to the Indiari trade.

Early attempts to organize an indigenous state are

evident around the Ghor and Suleiman Mountains in the tenth

century when Sheikh Hamid Lodi organized the local Afghans.

1

2

But the credit goes to his successor, sultan Bahlol Lodi,

who later built an empire in India patterned after the early

kingdom of Sheikh Hamid Lodi.

s

with the advent of the Mongol invasions beginning in

the 1220's, Afghanistan suffered tremendously. Flourishing

urban centers like Ghazni, Balkh, Bamian and many more were

laid to waste repeatedly by the Mongols.

6

Such instability

contributed to a decline in commerce causing Afghan society

to return to a more simple structure. Under the reign of

Timur-i-Lang (1336-1405), the irrigation system was

destroyed to the extent that Seistan, once fertile, became a

desert. However Timur's successor, Shahrukh (1407-1444),

encouraged development in the arts and commerce. During

this period large scale migrations of populations to the

north and east strengthened the Kabul-Ghazni-Kandahar axis.

By the sixteenth century the area today identified as

Afghanistan was divided between the Mughals, Safawids, and

Uzbek Khanates. However it was during this period that

literary sources mention indigenous struggles against the

Mughals around the Kabul-Peshawar-Kandahar axis. The

Roshani movement (1545-1585), interpreted by several

scholars as a national, religious, or class struggle, is an

example of tribes coalescing to overthrow Mughal power in

the region.?

Afghanistan's geographic location exposed its people to

3

many foreign invaders and populations. More importantly,

Afghan interaction with foreigners affirmed their sense of

identity as Afghans, which appeared in poetry and literature

around the 17th century. The Pushto poet, Khushhal Khan

Khattak's (1613-89) compositions illustrate the development

of an Afghan identity.8 Kushhal Khan Khattak's writings

relect a struggle between the Afghan nation and internal

tribal discord. In this dissertation, a nation is defined

as:

a community of people who feel that they belong

together in the double sense that they share

deeply significant elements of a common heritage

and that they have a common destiny for the

future. In the contemporary world that nation is

for great portions of mankind the community with

which men most intensely and most unconditionally

identify themselves, even to the extent of being

prepared to lay down their lives for it, however

deeply they may differ among themselves on other

9

J.ssues. .. .

A cultural identity of this sort was activated by Ahmad Shah

Durrani when he established a kingdom in the 18th century.

The Kabul-Ghazni-Kandahar axis became the basis of the

Durrani empire established in the 18th century by the

Suddozai clan. Under the Suddozais, much of the area known

today as Afghanistan was ruled by a tribal confederacy that

owed quasi-allegiance to the Suddozai clan. Then, in the

19th century, that area began to feel the repercussions of

European imperialism.

At that time Europe, after its industrial revolution,

4

held an economically and militarily dominant postion vis-a-

vis non-Europe. From this position, European powers, and

particularly Britain, were able to tap into market networks,

extract raw materials, and impose political power in

practically all continents. various authors have suggested

that British imperialism arose primarily to satisfy

metropolitan interests.

10

While economic motives may have

played an important role in the making of the British Indian

empire, they were only one of the many propelling factors

that may have guided British expansion.

D. K. Fieldhouse contends that imperialism stems from

peripheral factors, not from metropolitan interests

alone. 11 He elaborates:

A basic weakness of many Eurocentric theories of

imperialism is that they treat non-Europeans as

lay figures, whereas modern research has

emphasized the vast and decisive importance of the

way in which indigeneous peoples reacted to the

intrusion of Europeans and its associated

problems. Such reactions are intrinsic to a

peripheral approach to European expansion, for in

many places it is clear that the main if not the

only stimulus to alien occupation and formal rule

was the problem of deteriorating relations with

non-Europeans. 12

Previous studies of Anglo-Afghan relations, while stressing

the primacy of peripheral reasons for Britain's expansion of

its northwest frontier, virtually ignore Afghanistan's role

in generating this policy.13 Most of these stutiies view

Britain's relations with Afghanistan as a sub-category of

Britain's regional rivalry with Russia.

14

This study

proposes that, while imperial rivalry in the region

influenced British policy makers to pursue an aggressive

role towards Afghanistan, ultimately Anglo-Afghan relations

provided the major stimulus for imperial policy in the

region.

In order to analyze Afghanistan's active role in

influencing British imperial policy this study focuses on

Anglo-Afghan relations from 1838 to 1898, a period

predominated by British attempts to annex Afghanistan into

the British Indian empire. Twice during this period in

(1839 and 1879) British Indian authorities endeavored to

conquer Afghanistan. In neither instance did Russia

threaten India or its interests in the region. Nor did

economic factors figure prominently in the British decision

to try to annex Afghanistan. Instead, evidence suggests

that as early as in the 1830's British Indian officials

feared Afghanistan's capacity to instigate internal

instability, especially among the Muslim populations in

India.

Later in the nineteenth century, the British realized

that the large fighting force at the Amir of Afghanistan's

disposal posed a threat to imperial interests. It was to

neutralize this threat that British Indian authorities

initially proposed stationing British troops or personnel

5

6

inside Afghanistan. But, Afghan resistance to such efforts

led the British to adopt a policy of pre-emptive annexation.

Only after the British failed (twice) to conquer

Afghanistan, did they abandon their policy of annexation and

embark on a policy that separated a large number of eastern

tribes from the rest of Afghanistan and created an

Afghanistan dependent on British India.

By 1901, at the end of Amir Abdur Rahman's reign,

Afghanistan had evolved from a tribal confederation into a

territorial state with the gradual extension of governmental

authority within a fixed territory.lS Afghanistan's

territorial boundaries today are largely legacies of

nineteenth century European imperialists, " ... who often drew

lines without regard for cultural or ethnic realities and

sometimes even dissected meaningful, contiguous, geographic

units.".16 Afghanistan had acquired boundaries and other

basic features of a state. But at that time it still lacked

much of the infrastructure necessary for the development of

a modern polity.

The research for this study was conducted primarily in

New Delhi, at the National Archives of India, where the

Foreign Department Proceedings and Consultations were

extensively used. Of these the most important were the

Secret, Secret-F, Political - A & B, Frontier - A & B,

Memoranda - A & B, and Miscellaneous categories. The private

manuscripts of Lytton, Durand, Ripon, and Landsowne were

invaluable to this study. British Indian government

publications such as: The Annual Reports on the

Administration of the punjab; Gazetteer of the North west

Frontier; Report on the External Land Trade of the Punjab;

and Punjab Trade Reports were also used.

7

The Parliamentary Papers at the Nehru Memorial Library

in New Delhi were consulted, especially for the early period

in Anglo-Afghan relations.

In London, the documents in the India Office Library

and Records and the Public Records Office provided detailed

information regarding many decades of official

correspondence between London and India.

This study is divided into ten chapters. Chapter One

explores British policies towards Afghanistan in the early

nineteenth century. In the early years of the century, the

East India Company, established relations with Afghanistan

mainly because of its geo-political location, situated at

the crossroads in the overland trade between India and

Central Asia. The Board of Directors of the East India

Company felt that any extension of British influence in

Afghanistan would facilitate the East India Company's access

to the Central Asian markets, thereby enabling it to control

a large share of this important part of the world trade.

During this same period, Afghanistan, under the

8

Suddozais, emerged as a regional power, with socio-economic

and political institutions that combined Islamic and Pushtun

principles of organization. The British local political

officers in India concluded that a strong Afghanistan might

generate internal instability in India. Furthermore, French

Russian economic and political competition in the region

provided the British with justification for expanding their

Indian empire's borders, in order to compete more

effectively with such foreign rivals.

Chapter Two traces the formulation of the British

policy calling for the conquest of Afghanistan. In 1839,

under the pretext of removing Russia's influence from

Afghanistan, the British declared war on Afghanistan and

sent their military forces into Afghanistan in order to pave

the way towards greater British control over Central Asia's

economy. The British were surprised when the Afghans, under

the leadership of Amir Dost Mohammed Khan, his son, Akbar

Khan, tribal sirdars, and mullahs, defeated the British

army. The British now had to address the problem of a strong

Afghanistan they could not readily conquer.

Chapter Three analyzes Amir Sher Ali's attempts to

develop the Afghan state with limited resources and in the

shadow of Anglo-Russian rivalry. Amir Sher Ali embarked on

a modernization program that aimed to revive Afghanistan's

economy and introduce political and social reforms. These

9

changes laid the foundations for a modern centralized Afghan

state, with the introduction of a rudimentary parliament

that functioned to advise the ruler in state affairs. A new

political elite emerged in urban centers, more loyal to the

Afghan Amir than to their tribal groups. Although Pushtun

dominance remained solid, other tribes emerged as

influential partners of the state, diluting Qizilbash

dominance in the bureaucracy.

At the economic level, Sher Ali standardized the

monetary system and encouraged the payment of taxes in cash.

He also reorganized the Afghan military and made it into one

of the strongest institutions in the country. Subsequent

Afghan rulers concentrated much of their state resources on

the military. This diversion of funds left other

institutions relatively unattended. Later, when Amir Sher

Ali Khan did implement internal reforms, the British took

advantage of the situation and gradually penetrated into the

frontier region, pacifying some of the Pushtun tribes and

gaining control of several of the strategic passes. The aim

of this policy was to separate a number of the major tribes

from the Afghan Amir, and ultimately to increase British

control over Afghanistan.

Chapter Four probes into the forces leading up to the

second Anglo-Afghan war (1879-1880). In 1869 the British and

Russians began negotiations with the intention of carving

10

out their respective spheres of influence in Central Asia.

In 1873, they reached an agreement in which Afghanistan came

under British jurisdiction with a delimited northern

boundary separating it from Russia. Ironically, the Amir of

Afghanistan, Sher Ali, had no knowledge of this Anglo-

Russian pact until later.

The Viceroy of India, Lytton considered stationing

British personnel in Afghanistan. But ultimately the

proponents of the "forward school" succeeded in convincing

the British administrators that nothing short of occupation

would protect British imperial interests in the region.

Local political agents claimed that Russian advances in

Central Asia necessitated a British extension into

Afghanistan. Convinced that the time had come to assert

British paramount power in Afghanistan, in 1879 Lytton

initiated a war with Afghanistan.

Initial successes, enabled the British to impose the

Gandamak Treaty (1879) on Afghanistan, reducing it to a

protectorate state. But, this short-term victory ended,

when the Afghan nobility, the sirdars and the ulema

coalesced to drive the British out of Afghanistan. For a

second time British attempts to conquer Afghanistan had

failed. But in the process the British became aware of how

fragmented the country had become at all levels. The

British now became convinced that a weak and divided

Afghanistan, subject to British influence, would serve the

imperial objectives in the region.

11

Chapter Five looks at the rise of Russophobia in

nineteenth century British society. Information about

Czarist Russia became available to the British public in the

sixteenth century through the published reports of the

employees of the British Muscovy Company, who commented on

Russia's general backwardness. During the eighteenth

century Anglo-Russian ties were strengthened when the loss

of American raw materials led Britain to SUbstitute

materials obtained from Czarist Russia. By the nineteenth

century Anglo-Russian trade declined as both countries

acquired new colonies. Furthermore, because of competing

economic interests, Britain and Czarist Russia often found

themselves opposing each other.

Russsophobia gained a foothold in Britain in the late

eighteenth century because of events in Eastern Europe,

particularly the partition of Poland (1772). Polish

political refugees in England, advocating support for their

struggle against Russia through literature and political

organizations, aroused anti-Russian sentiments among the

British elites. The British demand for more information

about Czarist Russia, generated an outpouring of literature

on all aspects of Russia. The authors of this literature

generally potrayed Russia as "semi-civilized", ambitious,

12

and power hungry.

The rise of Russophobia in England coincided with the

rise of India's significance to the British Empire. British

political agents capitalized on Russophobic sentiments to

urge policy makers to expand the empire's border to contain

the Russian bogey. Subsequent British invasions into

Afghanistan, were justified to the public in England on the

grounds of an impending czarist Russian threat to India.

But, privately British officials seriously doubted Russia's

capacity to invade India or conquer Afghanistan.

Chapter six compares czarist Russia's expansion into

Central Asia to British Indict's activities in its northwest

frontier. Russian officials feared that British activities

in Afghanistan were aimed at preventing czarist Russian

penetration into Central Asia. Anglophobes, dominating the

Russian military, supported expansion initiated by ambitious

Russian military commanders whose careers, like those of

British political agents, depended on expansion.

Aside from political reasons, economic factors played

an important role in Russian expansion. Russian policy

makers, fearing that British products would come to dominate

the Central Asian market, tried to establish their control

in the region by monopolizing its trade. Although British

authorities potrayed Russia's drive into Central Asia as

part of a set of plans to threaten Afghanistan and India,

13

there was no actual verification of such plans.

By the 1870's it became clear to both imperial powers

of a need for a buffer zone between the two empires. But to

be an effective buffer zone, Afghanistan needed clearly

defined borders.

Chapter Seven analyses the formation of the modern

Afghan state under Amir Abdur Rahman. During his reign the

British and Russians formalized Afghanistan's ill-defined

borders. Having inherited a fragmented country, Abdur

Rahman attempted to consolidate his power and strengthen

the state apparatus and the military. But he was

constrained by the lack of manpower, capital and technology.

Traditionally in Afghanistan, state power was highly

decentralized and tribal units governed themselves according

to their own rules. Abdur Rahman tried to create an

absolutist form of government by breaking tribal power,

eliminating adversaries, and stationing his military

throughout the country. Having received religious approval

for his activities, the Amir tried to use Islam, rather than

tribal consent to legitimize his power.

The Anglo-Afghan wars had left the countryside

devastated. The absence of government authority allowed

independent tribal leaders to appropriate agricultural

surplus. Abdur Rahman attempted to monopolize trade in

Afghansitan, but the British opposed such measures that

14

denied profits to their merchants. As all the major trade

routes and passes were increasingly controlled by the

British, Afghanistan became vulnerable to British political

pressure. Furthermore, with a limited capacity to generate

capital, the Amir depended on British subsidies for the

success of any of his reforms.

Abdur Rahman fostered the growth of a Pushtun identity

through internal imperialism. Some tribes, such as the

Ghilzais, were compelled to migrate into non-Pushtun areas.

He disseminated literature couched in religious and

nationalistic phrases to encourage the tribes to resist

British encroachment. In 1893 the Durand Line separated a

major element of the Amir's power ba.se from the territory

defined as Afghanistan. Consequently, the political postion

of the border tribes remained volatile during subsequent

decades.

Chapter Eight briefly describes the actual

demarcation of Afghanistan's northern boundary, one defined

to suit czarist Russia's and British India's interests.

Afghanistan was not officially represented during their

negotiations. Despite Amir Abdur Rahman's insistence on

retaining control over Shignan and Roshan, the Viceroy of

India maintained that the 1873 Agreement had already

finalized Afghanistan's northern limits. British pressure

compelled Afghanistan to withdraw its troops from

15

territories held in the north. Moreover, Afghanistan was

obliged to relinquish any claims on Panjdeh and the Zulfiqar

Pass. Once Afghanistan's northern boundary was formalized,

British and Russian concerns over a possible confrontation

diminished.

Chapter Nine expands further on the definition and

demarcation of the the Durand Line. Although this line was

never finalized as a boundary between British India and

Afghanistan, it defined the extent of each of their power in

the area.

From the outset, British policy makers weighed two

options: either 1) to incorporate Afghanistan into the

British Indian empire; or 2) to sustain a weak and

fragmented state dependent on the British. By the 1890's it

had become evident to the administrators in India that the

latter plan was more viable. Meanwhile, British activities

among the frontier tribes increased, the British employed a

variety of methods to undermine the Amir's authority. Once

the British made alliances with certain segments of some

Pushtun tribe, then the British presented that segment's

petitions to the Amir claiming that those Pushtuns no longer

wanted to be under his jursidiction. In this way the

British eroded the Amir's power base. Faced with an

economic blockade and threat of another war, the Amir agreed

to sign the Durand Agreement. But the agreement was not

16

supplemented by a mutually agreed-upon map. Even otherwise,

the agreement was vague, and the British negotiators did not

possess acurate information about the frontier territory.

The Boundary Commission's efforts were often disrupted by

differences of opinion. It took two years (1894-1896) to

complete the mapping of the Durand Line, and even then

certain tracts like the Mohmand country remained unmarked.

Chapter Ten focuses on the aftermath of the Durand

Line, especially the reactions of the Pushtun tribes. The

British met with resistance and violence from the Pushtun

tribes in the frontier areas. The colonial administrators

attributed Pushtun defiance against their authority, to such

Pushtun characteristics as "fanaticism", "savagery", and

"anarchy". Colonial administrators often concluded that

brutal force was the only appropriate way to deal with

Pushtun resistance. This British failure to understand

tribal resentment continued to pose problems for the British

in the frontier until the end of their empire.

By 1897 the Durand Line demarcation proceedings had

ended. The Pushtuns to the east of the line resented being

separated from their qawm, and recognized an implicit

British agenda of denying Afghanistan a substantial fighting

force. British penetration into the frontier also increased

altercations between different Pushtun tribes. Those

Pushtuns who entered into British service were identified by

17

their fellow kinsmen as representing British interest in the

region. Such Pushtuns were sometimes seen by the tribal

elites as a new emerging political force challenging the

tribal status quo. Islam provided a unifying ideology to

which almost all sections of the population could be

mobilized by a network of local religious leaders. During

the 1897 and 1898 Pushtun uprisings against the British,

large numbers of tribals crossed the frontier border to join

in the anti-colonial movement. Although the Arnir denied any

personal involvement in the uprising, some of his officials

encouraged and even participated in channelling support to

the resistance. Key religious leaders often met with the

Arnir and cited his support to legitimize the jihad.

In almost every locality where the Pushtuns revolted

the symptoms of dissent were similar - British penalties,

loss of territorial integrity, intra-tribal differentiation,

British challenge to tribal status-quo, etc. The mullahs,

with the support of tribal leaders, transformed local issues

into a wide anti-colonial movement that set ablaze the

frontier from 1897 through 1898.

The concluding chapter reviews additional dimensions of

Anglo-Afghan relations and the shaping of Afghanistan as a

state, after the drawing of the Durand line.

18

1. Kakar claims that "Modern Afghanistan is almost co-

extensive with the land mentioned in the old Greek as

Ariana, in the old Persian as Airyana, in Sanskrit as Arya-

Vartta or Arya-Varsha, and in Zend as Eriene-veejo.". Kakar,

Hassan Kawun Government and Society in Afghanistan: The

Reign of Amir 'Abd aI-Rahman Khan (Austin: University of

Texas Press, 1979) p.xvi; Ghobar asserts that the term

Khurasan, or "land where the sun rises" was initially

applied to only portions of Afghanistan but eventually came

to mean the entire country. Ghobar, Mir Gholam Muhammad

Afghanistan dar Masir-i-Tarikh (Kabul: Books Publishing

Institute, 1967) in Persian p.385.

2. The geographer Abu sayid al-Balkhi was a product of

Balkh, an important intellectual center during this period.

Brown, Edward G. A Literary History of Persia

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956-59) vol.I

p.347-49, 353-54.

3. Fraser-Tyler, W. K. c:::;a=l

Development in Central and South Asia (London: Oxford

University Press, 1950) p.25-27.

4. Caroe, Olaf The Pathans (London: Macmillan and Co.

Ltd., 1958) p.124-125. According to Bosworth, the center

of the Ghaznawid empire was intentionally built in

Afghanistan because of its proximity to India. However, he

points out that the Ghaznawids utilized local institutions

to govern the population when he states:

.. institutions and practices can rarely be

transplanted en bloc from their [Ghaznawid]

homeland to a strange environment . The chief

innovation which the Turkish ghulam commanders

introduced into the village organisation of the

Ghazna region lay in the system of military fiefs

for their followers; but beyond this, there cannot

have been any question of imposing from outside a

completely new system in local affairs.

Bosworth, Clifford E. The Ghaznavids. Their Empire in

Afghanistan and Eastern Iran: 994-1040 (Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press, 1970) p.42-43.

5. Hammed ud-Din "The Loodis" The Delhi Sultanate ed.

R.C. Majmundar (Calcutta: Royal Publishing House, 1951);

The Lodi dynasty retained power in India between 1451 and

1526. For details on sources see, D.N. Marshall's The

Afghans in India Under the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal

Empire: A Survey of Relevant Manuscripts (New York: The

Afghanistan Council of Asia Society, 1976).

19

6. According to Juvaini, only a few artisans remained in

the city while the rest of the population were massacred.

'Ala aI-Din 'Ata; Malik Juvaini The History of the World

Conqueror ed. by Mirza Muhammad Qazvini translated by John

A. Boyle (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958),

vol.I p.131-133, 135; Similarly Ibn Bauta in his travelogue

observed that in the 1300's Balkh was totally abandoned and

Kabul resembled a small village. Ibn Batuta Travels in

Asia and Africa, 1325-1354 trans. H.A.R. Gibb (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1971) p.178-180.

7. The Roshani movement was led by Bayazid Ansari, a

religious scholar who mobilized the tribes by utilizing

traditional symbols and values. For details see: J.

Leyden's "On the Roshanian Sect and Its Founder Bayazid

Ansari" Asiatic Researches vol.XI, 1812; B.C. Smith's

"Lower-Class Uprising in the Mughal Empire" Islamic Culture

vol.XX nos.1-4 January, 1946; and M. Aslanov's "The

Popular Movement 'Roshani' amd Its Reflection in the Afghan

Literature of the 16th-17th Centuries" Afghanistan: Past

and Present (Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences, 1981).

8. The following phrases extracted from poems indicate that

Khushhal Khattak Khan grasped the notion of an Afghan

nation:

A. I bound on the sword for the pride of the

Afghan name,

I am Khushhal Khattak, the proud man of this

day.

B. I alone am concerned for my nation's honour,

The Yusufzais are at ease, tilling their

fields ...

C. For full five years the tribal sword has

flashed

Keen-edged and bright, since first the battle

clashed

Upon Tahtarra's peak, where at one blow

Twice twenty thousand of the Mughal foe

Perished, wives, sisters, all that they held

dear,

Fell captive to the all-conquering Afghan

spear.

Cf. in Caroe, Olaf The Pathans p.237-246.

9. Young, Crawford The Politics of Cultural Pluralism

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) p.67.

20

10. Hobson's classic study attributes Britain's drive to

acquire colonies to a "conspiracy theory". According to this

"theory" special pressure groups influenced parliamentary

politics and the public media to adopt an expansionist

foreign policy that benefitted these groups. Hobson, John

A. Imperialism: A study (Ann Harbor: University of

Michigan Press, 1902); Lenin, too, offered an explanation of

imperialism as emanating from metropolitan interests, with

capitalism in its highest stage necessitating overseas

expansion for profits, raw materials and alternative

markets. Lenin, Vladmir I. Imperialism: The Highest stage

of Capitalism (New York: International Press, 1939).

11. Fieldhouse, D. K. Economics and Empire, 1830-1914

(London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1973, 1984).

12. Ibid. p.81.

13. Malcolm Yapp, in an excellent study of British

activities in India's northern borders, asserts that the

reason for expansion originated in the periphery. British

political agents, hoping to enlarge their spheres of

interest, advocated within the appropriate channels of the

Indian bureaucracy the need to extend the empire's borders

in order to protect British India from some impending

threat. Yapp, Malcolm E. strategies of British India:

Britain, Iran and Afghanistan, 1798-1850 (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1980).

14. Singhal, D.P. India and Afghanistan, 1876-1907

(Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1963); Ingram,

Edward A. The Beginning of the Great Game in Asia, 1828-

1834 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); Alder, G.

J. British India's Northern Forntier, 1865-1895: A study

in Imperial Policy (London: Longmans, Green & Co. Ltd.,

1963); and Chakravarty, Suhash From Khyber to Oxus: A

study in Imperial Expansion (New Delhi: Orient Longman

Ltd., 1976).

15. Crawford Young describes nineteenth cenutry Afghanistan

as a territorial state possessing such major properties as

territoriality and sovereignty as a consequence of Anglo-

Russian imperial rivalry in the region. Young, Crawford

The Politics of Cultural Pluralism (Madison: University of

Wisconsin Press, 1976) p.67. However, during the reign of

Ahmad Shah Durrani (1747-1772), sovereignty had already been

established, along with nominal control over much of the

territory defined today as Afghanistan.

21

16. Dupree, Louis "Afghanistan: Problems of a Peasant-

Tribal state" Afghanistan in the 1970's ed. Louis Dupree

& Linette Albert (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974) p.2.

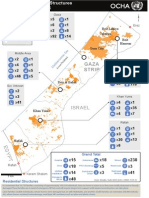

MAP 1.

PCRSIA,

., Kirman

ARABIA

Herat

..

0..

-xc:J'

.. K.abul

Ghazni

II .

Ismai

aD(-' 0 . Khan

------- Ghi lui

.,Q uett a

Arahian Sea

EMPIRE OF AHMAD SHAH DURRANI

A.D. 1762

L. Dupree, 1980

80 /JIJ'

AFTER: G. SINGH, 1959,286

o 200 400 600

____ I I

MILES

\

, N 0

Nllr"b

ocJtJ

j5

N

N

- CHAPTER ONE -

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AFGHANISTAN UNDER THE SUDDOZAIS

Afghanistan as a recognizable state was established in

1747 by Ahmad Shah Durrani, an Afghan military commander of

the Persian ruler Nadir Shah Afshar. Political instability in

neighboring areas enabled first the Ghilzais in Kandahar, and

then the Abdalis (Durranis) to declare their independence from

Persian rule. After the assassination of Nadir Shah Afshar by

Turkmen tr ibes in June, 1747 , Ahmad Shah Baba Durrani, 1

supported by his armed tribal contingents, returned to

Kandahar and proclaimed himself ruler of the Khorasan

provinces.

2

The Suddozais are a sub-division of the Popalzai

clan, who belong to the Durrani tribe. The Barakzais also

belong to the same tribe but are a sub-division known as the

Mohammadzai, and have been the rivals to Suddozai rule

throughout Afghan history.

According to the historian, Ganda Singh, Ahmad Shah

Durrani appealed to all Afghans for loyalty through religion,

patriotism and national honor.

3

From 1747-1758 Ahmad Shah

expanded his empire to incorporate such fertile tracts as the

Punjab, Sind and Kashmir. Consequently, Afghanistan's

position in the Central Asian trade was strengthened, as these

new dependencies produced commodities that were in demand in

widely-scattered markets.

Ahmad Shah Durrani and his followers carried out

23

24

approximately eight campaigns into India that brought them

much wealth and land. Seeing this, many tribes were lured to

support Durrani control on condition they were assured a share

in the booty which in turn increased their positions in

society. Arranged marriages also forged alliances among

several powerful tribes and ethnic groups. It could be argued

that Ahmad Shah Durrani, in these ways, established a state

that covered the core regions today identified as Afghanistan

along with the additional territories of Persian Khurasan,

Turkestan, Punjab, Kashmir, and Baluchistan.

4

Territoriality

and sQvereignty, the key properties of a state, can be

identified in this period of Afghan history. Ahmad Shah

Durrani's extension of state power over these areas, though

not entirely comprehensive, was achieved through taxation,

military recruitment, public works and agricultural projects.

In 1772 Ahmad Shah Durrani died of cancer, and his son

Timur Shah succeeded him as ruler of Afghanistan. One of

Timur Shah's first moves was to transfer his capital from

Kandahar to Kabul, in order to break away from the dependency

of the Kandahar nobility. This caused much resentment among

the Kandahari Pushtuns, who had been a supporting political

base of Ahmad Shah's empire. Timur Shah offended them further

by incorporating Qizilbashis ( a Shiah minority of Turkmen

origin) into his army and also using them as personal

bodyguards. The resentful Pushtuns made several attempts to

25

overthrow Timur Shah. For example, in 1791 Mohmand and Afridi

tribesmen rebelled, espousing the legitimacy of another heir's

claim to the throne. Although the Mohmand and Afridi

tribesmen attacked the Bala Hissar of Peshawar, their efforts

finally failed, and many of them were arrested and put to

death by Timur Shah. Peshawar served as the winter capital of

Afghanistan; consequently it's nexus with Kabul was not only

politically but also economically significant. Much of Timur

Shah's reign was spent crushing internal revolts to bring

stability throughout the country. In 1793 he died in Kabul.

When Zaman Shah, the fifth son of Timur Shah, inherited

the empire, portions of the Punjab and Sind still belonged to

Afghanistan. His efforts to regain lost territory led to his

forming an alliance with Ranjit Singh, a petty chief in the

Punjab, and capturing Lahore. Ranjit Singh was then appointed

the Governor of Lahore and in turn he acknowledged the

suzerainty of the Afghan ruler.

By the turn of the nineteenth century Britain was gaining

paramountcy in India, and her active policy of expansion was

sometimes justified by invoking the "Afghan threat". In part

this notion was affirmed because some Muslims in India, a few

of Afghan origins, openly advocated Afghanistan's intervention

in Indian affairs in order to preserve Mughal power which by

this time was declining. In fact, Afghanistan's intervention

was perceived by many as a natural or logical step because

26

Babur, the progenitor of the Mughal empire, had once been the

ruler of Kabul. Thus, it seemed to some Indian Muslims that

Zaman Shah was the only hope in India for Islam.

5

with Zaman

Shah now in control of Lahore, the British began to recognize

the possibility of a real threat of Afghan expansion into

India.

Although the British saw Zaman Shah's eastward campaigns

to be motivated primarliy by the desire for territory, Zaman

Shah may have had other, more pressing, reasons. The empire

he inherited was in disarray and was in dire need of capital.

Previous rulers in Afghanistan had periodically obtained

capital through plunder.

6

Ahmad Shah Durrani's kingdom

significantly relied on plunder as a source of income. In the

process of engaging in plunder, territories were often

conquered becoming part of the Afghan empire and thus

providing additional revenues to the state treasury.

The British, according to Malcolm Yapp, did not all

necessarily believe in the "Afghan threat". However, they

perpetuated the myth in order to justify their designs in

India. For example, they cited the presence of Afghans in

Lahore to increase their troop strength in Oudh.

further argues that,

. a forward policy was expressly and explicitly

forbidden by the East India company's Board of

directors, by the British Government and by the Act

of Parliament .. British India was allowed to go to

war only if it were attacked ... . These rigid

Yapp

prohibitions, could be dissolved by the solvent of

the external enemy.7

27

During the eighteenth century the French had threatened

British interests in India especially in the Carnatic region

of southern India. However this rivalry had diminished by the

nineteenth century. By now the British administrators were

more afraid of internal foes than of external enemies and they

felt particularly uneasy with their Muslim subjects, who they

feared, had sympathies with the Mughal power or wanted to

align themselves with other Muslim powers. This fear prevailed

to the point that some British conjured up grand plots that

saw external powers forming alliances with internal dissidents

against the British allover India. In order to prevent this

from happening the British adopted the policy of expansion to

the north-west under the guise of creating alliances to

protect their rule in India.

Meanwhile, revolts within his own empire forced Zaman

Shah to return to Kabul. In fact the Barakzai Sirdars of

Kandahar, led by Payinda Khan Mohamadzai, were suspected of

intrigues, and Zaman Shah had the leaders executed.

8

Fatteh

Khan, the son of Payinda Khan, joined forces with Shah Mahmud

of Herat, a half-brother of Zaman Shah, and overthrew the

King. Zaman Shah was barely thirty-two years old when he was

taken captive by Shah Mahmud and blinded. He spent the rest

of his life in Lodhiana as a pensioner of the East India

28

Company.

Shah Mahmud held the Kabul throne for three years (1800-

1803) after which he was replaced by Shah Shuja (1803-1809).

Shah Shuja was Zaman Shah's full brother and Mahmud's half

brother. Rivalry between Mahmud and Shuja plunged the Afghan

kingdom into chaos and disorder at all levels. The political

elites of the ruling stratum were divided, and the power of

the central government weakened. As the Kabul government

became bogged down with matters of its own survival, local

amirs began to carve out territories for themselves. In many

instances, the local amirs increased the taxes and placed

undue demands on the ra'iyah in order to maintain their local

military forces. As a result economic disorder prevailed,

forcing many tribes to resort to raids and looting, and

consequently trade suffered.

Meanwhile, Anglo-French competition in the region

prompted Lord Minto decided to forge alliances with

Afghanistan and Persia to counter French designs. If

Afghanistan and Persia could be convinced of British India's

friendship, they might be less friendly to the French

influences and more willing to protect British interests. On

Febuary, 25, 1807 Mountstuart Elphinstone, the British envoy

to Kabul, was sent on a mission to meet with Shah Shuja in

Peshawar.

9

This marked the beginning of official relations

between Afghanistan and British India. Elphinstone sought an

29

alliance with Kabul in the event France initiated any

hostilities towards British interests in India. However if

Persia were to form a coalition with British India, the

off icials in Calcutta felt that Afghanistan's role in the

regional power play would not be as crucial.

Elphinstone's primary function at his juncture was to

gather intelligence about the Afghan kingdom. When he arrived

in Peshawar, Afghanistan was plagued by political rivalry

between Shah Shuja and his half-brother Mahmud. Instead of

there being a central government, power in Afghanistan was

bifurcated, with Shah Shuja's base in the Kabul-Peshawar

region and Shah Mahmud's base in Kandahar. In the peripheral

areas local commanders or tribal leaders were emerging as

petty rulers of their own regions.

The British mission sent to Afghanistan to meet Shah

Shuja actually strengthened his image as a ruler. On June 17,

1809 an agreement was concluded between Shah Shuja as ruler of

Afghanistan and the British Indian government. This agreement

guaranteed that, should the Persians and French invade against

Afghanistan, British India would join in the defence of

Afghanistan primarily intending to prevent such hostilities

from spreading into India. 10 The importance of this

Agreement was that mutual friendship was established between

the two parties which hereafter was to shape the course of

events in Afghanistan's history.

30

One of Shah Shuja's main reasons for forging this

alliance with the British was to thwart Shah Mahmud's efforts

to overthrow him. Shah Shuja had hoped that by signing such

an agreement with the British he could acquire some political

legitimacy and also obtain some financial aide. According to

the Afghan historian M. Ghobar, since Shah Shujas's power was

only nominal, throughout Afghanistan local sirdars began to

carve out territories of power for themselves. They were thus

in constant rivalry against not only the ruler but also each

other. Tax revenues to the royal treasury in Kabul began to

diminish rapidly because many of the local sirdars stopped

paying provincial dues to the government.!! In an effort to

control the various rebellions, Shah Shuja spent much of his

treasury raising armies and launching expeditions. They,

however, met very little success. The campaign to Kashmir,

for example, was a total failure. As his funds began to

diminish, Shah Shuja faced a situation of general disorder,

even in Peshawar. Finally, in 1809, Shah Mahmud, with the

help of the Qizilbash ethnic group from Kabul marched from

Kandahar and captured Kabul. The conclusive event was the

defection of .Shah Shuja's troops and advisors when they were

en route to battle Shah Mahmud in Jalalabad. Shah Shuja was

forced to flee into exile, joining his blinded half-brother

Zaman Shah in the Punjab. When Shah Shuja arrived there, the

British increased the allowance for the royal family to

31

Rs.50,000 per annum. Hence, one result of the 1809 Agreement

was that the British found an ally in Shah Shuja, who now

remained in exile with their financial support. In the years

to come, he was to play an important role representing British

interests against his own country.

Shah Mahmud's reign ushered in the end of the Suddozai

clan's rule in Afghanistan. Shah Mahmud, even with the help

of his son Prince Kamran, vIas incapable of controlling a

country faced with political and economic upheavals. A period

of civil war prevailed until a different clan of the Durranis

known as the Barakzais, led by Dost Mohammad Khan, was able to

gain power in Kabul and unite all opposition forces.

A major Suddozai contribution to Afghanistan's history

had been the founding of the country in 1767, which became the

basis towards the development of the state.

they had participated in the political

Subsequently,

development of

Afghanistan. For example, Ahmad Shah Durrani expanded the

resources and revenues of the country by conquering and

including new territories into his empire. He left behind him

a vast empire including the following areas: Herat, Persian

Khorasan, Balkh, Khulam, Kashmir, Multan, Sind, Peshawar,

Kandahar, Kabul and Baluchistan.

12

His son, Timur Shah, on

the other hand, pursued his father's goals of development but

was not enthusiastic about conquering additional territories.

Instead, he focused on the internal administration of his

political kingdom.

32

Elphinstone notes that Timur Shah's

" policy was directed to secure his tranquility . " .13

Masson's historical verdict is less kind when he says that the

Shah, as is typical of many rulers, lived on the reputation of

his father.

14

When Timur Shah died, he left behind twenty-

nine sons and ninteen daughters - a situation which led to the

fragmentation of the kingdom through fraternal discord and

rivalry. IS

POLITICAL STRUCTURE OF THE DURRANI REGIME

Afghan society mirrored the patterns of organization

found in medieval Islamic dynasties of the Buyyids (10th

C

),

Ghaznawids (10th-11th

C

), and the Seljukids (11th -12th

c

). The

Durrani government, in its early stages, consisted of a tribal

confederation with Ahmad Shah at its head, having paramount

authority to levy taxes and collect money in times of war.

However, decision-making did not rest solely on his authority.

He was assisted by a councilor jirgah comprising of the

various tribal leaders or elders. Each tribe had its own

customary laws according to which their internal matters were

governed, and Ahmad Shah followed a policy of non-interference

in such areas. In general, Fushtunwali tribal customs

prevailed over Islamic practices whenever they differed. For

example in the event of trying criminal cases, " . trials

(were) conducted before a Jirgah, which (was) composed of

Khans, Maliks, or elders ... " .16 The mullahs' assistance

33

was sought here, not to administer justice but rather to

provide advice if needed. Also, before the jirgah was

convened, the usual Muslim prayers were offered, after them a

Pushto verse was cited stating that, "Events are with God, but

deliberation is allowed to man.".17

Ahmad. Shah's rudimentary form of government was gradually

transformed as new lands were conquered, providing additional

revenues and military personnel independent of the tribes.

The Durrani Sirdars were part of the nobility and were taken

into the jirgah to discuss the matters of the state.

Simultaneously, their powers of revenue collection and

administration of justice were curbed. As the

bureaucracy expanded, revenues were collected

officials, and qazis were appointed to partake

king's

by his

in the

administering of justice. This was the situation during the

peak of the Durrani Empire.

At the top of the Durrani Empire was the monarch whose

function was to maintain peace and order in society. His

title was Shah-i-Dur-i-Duran or "King of the Pearls", a

position that was always to belong to the Suddozai branch of

the Durrani tribe. However, the rule of primogeniture was not

affixed which caused much confusion in the event of the death

of the king. By tradition the Durrani Sirdars were to meet in

council to decide the heir to the empty throne. However, such

a council typically became merely a front for the shifting of

34

alliances and rivalries among the nobility.

The ruling ideology was a combination of Islam,

Pushtunwali and military autocracy. In principle, the entire

country's destiny rested on the will of the Shah. He

controlled the military levies, commanded the armies, and was

the sole arbitrator on crimes against the state.

18

But the

King had no right to take the life of a Suddozai.

Furthermore, the Shah delegated his power to the tribal

chiefs, who had absolute power within their dominions. The

only check on their power was the fear of revolt of their

subjects. To resist such revolts, they maintained their own

armies. As long as the tribal chiefs transmitted the

appropriated revenues to the royal treasury, the King pursued

a policy of non-interference.

In the administration of the government, the King was

assisted by the following: 1) Vazir Auzim, or Chief Minister,

who had the entire control over the collection of revenues and

over the internal and external political officers; 2) Munshi

Bashi, or Chief Secretary, who dealt with the ruler's

correspondence; 3) Hicarah Bashee, or Head of Intelligence,

who was in charge of the informants and managed crimes and

punishments; and 4) Zubt Begi, who confiscated property.

There were also several functionaries of the Royal Court and

household such as: 1) Mir Akhor or manager of the house; 2)

Ishakaghazi Bashi or Master of Ceremonies; 3) Arzbegi or

35

Announcer, who had several criers of the court; 4) Chous

Bashi , who presented grants and dismissed the court; 5)

Sandukdar Bashi, who was the wardrobe keeper; 6) Mushrif, the

Pri vate Treasurer of the King; and 7) Peshkhidmats, or

eunuchs, who often had much influence on court affairs.

The kingdom was divided into twenty-some provinces of

which eighteen were governed by a Durrani Sirdar called the

Hakim, who also commanded the militia and collected revenues.

In these matters he was assisted by the qazi and the head of

the division of the tribe. Thus, his authority was supported

by other subordinates. The administration of justice in the

rural areas was under the sirdar, who was counseled by the

qazi. At least this was the case in the latter part of the

Suddozai reign. Formerly the j irgah had settled the disputes.

Gradually one sees the central bureaucracy replacing tribal

functions. The police functions were performed by the

mirshab, mohtasibs, daroghas and kishikchis (watchmen). In

principle, the King had absolute power; therefore all regal,

military and jUdicial functions were united in one person. In

fact much did depend on the arbitration of the King,

especially assisted by his qazis, muftis and maulvis.

19

In

cities, especially complaints were referred to the King, who

in turn directed them to the qazi according to the nature of

the case. In cases of treason, the monarch was the sole judge

but, he was prohibited, by tribal custom, from taking the life

of a Suddozai.

THE MILITARY

36

The army in Afghanistan was in general controlled by the

sirdars, especially during the earlier years of Ahmad Shah's

reign, when he relied on the support of the tribes from

Kandahar. Gradually this arrangement began to change as he

recruited mercenaries from Central Asia to serve in the army.

In time some of these mercinaries emerged to become

influential commanders. Their relationship to the King was

one of loyalty to a patron, and this loyalty continued as long

as they received financial support. such mercinaries,

however, could be influenced to join rival camps, if those

camps provided them with more generous financial support.

In contrast were the Ghulam-i-Khaas, who were slaves

captured during the various campaigns. Some, who were reared

and fostered at a very early age by the King had strong ties

not only to the ruler but also to the royal family and their

sense of obligation was based on an emotional attachment

rather than on material gains. In fact, so strong was the

bond between the ghulam to his master that it was a more

patriarchal relationship. As a result, some of these slaves

became the King's most important source of power independent

of the tribes. Mottahedeh, in analyzing the role of ghulams

in Islamic society, states:

Essential to the survival of each ruler was the

corps of ghulams whose training he had himself

fostered, and who shared the strong affection that

ghulams usually felt only for patrons who had

sustained their careers in this manner. These were

the 'king's men' in a very special way, and no one

else was supposed to tamper with their affection of

the King or call them to account i and outside

parties seldom did so ... 20

37

The Ghulam-i-Khaas division in the army was divided into

separate corps and were commanded by officers named Qular

Aghasis who were responsible to the King. When the Suddozai

dynasty crumbled, the Ghulam-i-Khaas disintegrated to be

replaced by a new group.

Timur Shah's reign, in a move to diversify his source of

power, incorporated the Qizilbash into his army. The sirdars

of the tribes were not pleased with this, but this provided

the King with more leverage against potentially disaffected

sirdars. Inspite of these new elements, towards the end of

the Suddozai dynasty the majority of the fighting forces were

still provided by the tribes of which the Durranis furnished

12,000 men.

21

The Ghulam-i-Khaas still existed, as did

newly-incorporated ethnic groups. The iljauri, a militia of

poorer classes, were paid through village taxes. However, in

times of instability, these men often remained unpaid, and

they sometimes revolted. The tribes near Kabul were almost

"always employed as iljauri during times of emergency. 22

While some tribes were given rent-free lands for their

military service, others were paid directly from the royal

38

treasury.

REVENUES OF THE EMPIRE: ECONOMIC BASE

state revenues were derived from several sources,

including land revenues, town duties, customs, fines and

provisions supplied to the King and his army when they passed

through an area. The major source of income came from

agricultural revenues; in times of war a share of the spoils

became an added source. Agricultural income was paid in kind

and in cash. In earlier times, state funds had increased with

the rapid accumulation of territories. But by the end of the

18th century, most of the lands had been distributed in the

form of jagirs. This meant large parcels of lands were given

to chiefs who inherited the right to collect and keep the

revenues in return for providing military service for the

ruler.

23

Collection of farm taxes were in actuality the task

of tribal sirdars or nazims, who in turn transferred this duty

to the village headmen. The ancient custom of wesh, (i.e.,

the periodic redistribution of land among tribal clans) was

also practiced. It was a form of communal tenure which was

inalienable. In some instances, entire villages were

transferred from one tribe to another. However, as time

passed, this practice fell into disuse as people began to

recognize the advantage of fixed tenure. In time, the

alientation of property led to the formation of a class of

appropiators of the surplus. They became the elites in the

39

society, i.e. the maliks, khans, ulema, etc. who actively

participated in the political affairs of the country.

In theory the state was the supreme owner of all lands

and had the right to collect taxes, a right that it

transferred to the sirdars. This was commonly practiced

throughout the Islamic world and was especially utilized under

the Buyyids and successive dynasties in medieval times.

Military officers were granted the lands, but not on a

permanent basis: n the area granted and the grantee were

constantly changed ... the system weakened government

supervision and led to more pillage rather than to the

development of the lands granted.

n24

In contrast the jagirs

in Afghanistan were more permanently assigned unless the

central government changed hands. This practice allowed

commanders to develop territorial claims in times when

authority was weak. Although the actual improvements of lands

were, in principle, was in the best interest of the

cultivators assigned to those lands, however, there were cases

where maximum taxation impoverished the cultivators. Very

heavy taxes tended to be imposed in times of political

instability when other sources of income were being diverted

by the jagirdars or tomandars. It is reported that Ahmed

Shah's revenues amounted to thirty million rupees annually. By

contrast, Elphinstone estimates Shah Shuj a's treasury was

receiving only 900,000 rupees per year.

25

As more and more

40

lands were assigned as jagirs, less income went into the royal

treasury.

The cities in Afghanistan sheltered heterogeneous groups

of people, including the nobility and their followers, many of

the soldiers, and the ulema. The city merchants were primarly

Tajiks, Persians or Afghans. According to Elphinstone, the

shopkeepers and artisans were organized into thirty-two

trades.

26

Each guild had a kudkhuda, or chief, that

represented them in dealing with the government. Their

services were not taxed, but duties were imposed on whatever

products they exported. Furthermore, when the royal entourage

was in town, their services were demanded, for which they did

receive pay and from which they profited very little.

Merchants paid customs duties and road taxes, which in times

of prosperity annually brought into the treasury rupees

60,000-70,000 rupees. However, during Shah Shuja's reign

(1803-1809), such duties and taxes produced only rupees 25,000

annually. 27

Afghanistan's external trade was dominated by Hindus,

Sikhs, Jews and Armenians. However wi th the decline of

overland trade these communities diversified their

professions. The Hindus and Sikhs, aside from trade,

monopolized banking, goldsmithing and horticulture. Bankers

from these communi ties rose to prominence in the Durrani

empire. Originally they were merchants from Shikarpoor who

41

had financed several of Ahmad Shah's military campaigns. In

return they had received a percentage of the captured booty.

In some instances this booty was left under their management.

They, in turn, often sold the booty and put the money from the

loot back into circulation. 28 The Hindu merchants also

provided the Durranis and other members of the nobility with

necessary supplies as well as luxury items. These merchants

sometimes made loans not only to the government but also to

other officials, who at times committed the entire revenues of

their provinces as collateral. Many of the Hindus and sikhs

also found employment with the state as treasurers, scribes,

book-keepers and secretaries. Gradually members of these

communities amassed much capital and gained political

power. 29 G. Forester notes that Timur Shah's income was

managed by these merchants who were specially protected by the

government. 30

Afghan Jews turned towards other professions like

medicine and specialized in lambskin trade.

31

Armenians were

a significant force in the overland trade of spices, silk and

wool, especially since they had established posts throughout

the ottoman empire and Persia. Both the Jews and Armenians

were settled in Afghanlstan by Nadir Shah Afshar to encourage

the Indo-Persian trade.

32

In time, British India's

monopolization of external affairs, and poor

economic conditions within Afghanistan, compelled the Jews and

Armenians to leave the country.

THE RELIGIOUS ESTABLISHMENT

42

In a discussion of the internal structure of the Durrani

Empire, the religious establishment must also be included. At

this period in Afghan society, the ulema was gradually

evolving into an important group within the political

structure. Al though there were many religious men throughout

the country, they did not belong to any hierachical body, nor

was there any unity in doctrine. Many of them, e.g., sufis,

pirs, sayids, faqirs, khwajahs, etc., belonged to one tariqa

(mystic order) or another, and their strength was derived from

their followers. Of the several tariqqas, the Naqshbandiyya

order was the most prominent. In the rural areas these men

performed the necessary Islamic rituals and satisfied the

spiritual needs of the people. The fees for their services

and the charitable donations given in-kind supported the local

mullah.

In cities and towns could be found organized religion in

the form of the ulema, who were theologians or scholars of the

faith interpreting daily matters according to the principles

of Islam. sometimes they became involved in politics because,

"As the highest body among the Sunnis the ulema issued fetwas

on subjects concerning religion and state.". 33 Their moral

authority transformed into political power through the

patronage of the crown. Charitable ouqaf lands were given to

43

the religious men, and through the income from these lands

they were able to support themselves. The administration of

the lands was in their own control, and the surplus they

appropriated was not subject to any tax. At the provincial

level, tribal sirdars at times gave charitable lands to the

ulema. This meant that the ulema sometimes came to own large

tracts of land. During this period, the ulema could not be

perceived as a monolithic body owing allegiance to one

authority. The group's common bond was their knowledge of the

theologoy or ilm; aside from that, they had different

overlapping sources of loyalties. 34 For example, the

political interests of the ulema in Herat differed from the

political interests as those in Kabul. Many of the ulema

identified their interests with those of their patrons.

In Kabul, the crown supported a group of religious men

who carried out various functions. The Mullah Bashi was the

head of the ulema under the King. The peshnamaz ( or the

monarch's Imam) read prayers to the King. If the King went on

a journey he was attended by the Imam Parekab. At the royal

mosque the Shah patronized, one Imam who recited the prayers

on Fridays and on Id. Another Imam, subordinate to the

previous one, led prayers every day except Fridays and

holidays. At the Idgah, the actual place where the festical

of Id was celebrated, the Mullah-i-Khatib recited the prayers.

Finally there were the muderris {who were basically

44

instructors at the mosque) and the muezzin (who called

believers to prayers).

outside of Kabul, in smaller towns, the sheikh-ul-Islam

managed the administrative affairs of the ouqafs while the

suddur served as bookkeeper. On the recommendation of the

Mullah Bashi, the king appointed various qazis, muftis, etc.

who served the king in the judicial affairs of the towns.

They received no regular salaries; instead they were provided

with fees for their services.

In the later part of the century, Islam, the established

religion in Afghanistan, was slowly gaining ascendancy in the

ruling stratum. Even so, the mullahs were not an entrenched

organized unit in Afghan society. Things were different in

Peshawar and its adjoining regions. Elphinstone, in

describing the powerful influences of the mullahs in Peshawar

says, I! I believe they are more feared than loved .. " and in

comparison, " ... in the west (Afghanistan) their power is much

more limited and their character much more respectable. ,,35

Amidst the political chaos in the latter part of the

Saddozai reign in Afghanistan, trade had declined, bringing in

only trifling amounts of revenue. For example in Kabul alone,

where previously the annual income from trade had been betwen

60,000 and 70,000 rupees by the early 1800's it was a mere

25,000 rupees per year. 36 As more and more lands were

assigned to jagirs, the income to the royal treasury steadily

45

declined. Many of the jagirdars took advantage of the rivalry

between Shah Shuja and Shah Mahmud to carve out for themselves

centers of power. One case in particular was Ranjit Singh,

the sikh leader, to whom Zaman Shah granted Lahore as a jagir

for his services. This sikh leader gradually emerged to

become one of the major challengers to Afghan rulers.

RANJIT SINGH AND BRITISH STRATEGIES

Lahore, the capital of the sikh state, was bountiful in

agriculture and cotton. Its revenues provided Ranjit Singh

with a strong financial base. Ranj it Singh was able to expand

his power north-east across the Indus and southwards to the

borders of Sind. The chaotic situation in Afghanistan

provided the sikhs a good opportunity to extend their control

westwards. In 1803 Lord Minto sent Charles Metcalfe to Lahore

to try to include the sikhs in the British strategic plans to

form an alliance with Afghanistan against the French.

Metcalfe discovered soon enough that Ranjit Singh did not

favor an alliance with Afghanistan because of the sikh

leader's had plans to expand westward. Furthermore, for the

Sikhs, the possibility of a French invasion seemed too remote.

During this period the British were struggling to gain

paramountcy in India. After the Battle of Plassey (1757) in

Bengal, the East India Company acquired the diwanship of

Bengal and several of its adjacent districts. Between 1786

and 1805 the British were able to seize large territories in

46

the south near Madras. From 1838 onwards, British direct rule

was established in central and north-west India. The reasons

for expansion came from a combination of several factors. In

many instances the decision to expand power was made in India

not in England, and the idea was initiated by political agents

at the scene who then suggested it to their superiors. 37

Involved in these expansionist policy suggestions were often

motives of self-interest justified in terms of an external

enemy or some internal threat.

During this period, the external enemy was often the

French whose threat was not as serious as it was described to

be, but whose presence was used to justify carrying out

policies in India that otherwise would not be well-received in

London. Another plausible foe were the Afghans whose danger

lay in their capability of causing instability within the

British Indian dominions. However by the 1800's with the

political fragmentation of the Suddozai Empire the Afghan

threat declined, and offered a weak argument for expansion in

British political circles, atleast temporarily.

Aside from political interests, economic motives figured

in the expansionist designs of the British in the sub-

continent. Up to the end of the eighteenth century India had

been a source of luxury goods for British consumers at home.

However, by " ... the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

India became a market for Britain's manufactures and a source

47

of raw materials for her expanding industries.".

38

The sub-

continental interior was increasingly opened for the purpose

of extracting the resources needed for the development of the

English markets. Writing on this subject, Karl Marx stated

that " . The English millocracy intend to endow India with

railways with the exclusive view of extracting at diminished

expenses the cotton and other raw materials for their

manufactures. 11.39

Channels of communication were improved or built linking

the interior regions of India to the world markets. Whether

or not a new territory was acquired by the British often

depended on the commercial value of the region. For example