Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

History Labour

Hochgeladen von

Keith CampbellOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

History Labour

Hochgeladen von

Keith CampbellCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Banking, Insurance and General Workers Union

History of the Movement

Intro Grapes of Wrath - Conditions of the Working Class The early 1930s saw the steady deterioration of working class living conditions. The two main sectors of the agricultural economy -sugar and cocoa- had remained depressed since the drop in world prices in the early 1920s. The post-war depression and the mechanisation of the production process had reduced the number of workers employed. The great depression also led to the lowering of wages and rising costs and reduction in the working hours. This meant that workers had to live on earnings in the 1930s that were approximately 2/3 of what they received in the 1920s. The sugar barracks with their open, slimy drains, overcrowding and filthy latrines were described by John Jagger as: "....words fail me when I try to describe the conditions we saw ..... perhaps most dreadful of all were the round iron cisterns at each door containing the drinking water for residence, in which were every creeping and crawling thing imaginable, plus endless masses of mosquito larvae" Workers were paid their wages not in cash but with purchase orders which could only be redeemed at the local shops. Cheating of illiterate people, indebtedness at very high interest rates, lower prices for crops mortgage to shops, reduced access to further credit, all led, for countless people, to the loss of their holdings, either to the estates or to the shops. The workers in the oilfields feared no better notwithstanding the substantial margin of profits. The earnings of the average oil worker were less than the wages he earned in the 1920s. Moreover, in the oilfields, prices for basic consumer items tended to be higher than in other parts of the country. Lt. Colonel H. Hickling, manager of Apex oilfields, started a cost of living index based on price increases and showed by his calculations that food prices had risen by 17% between 1935 and 1937. He, in early 1937, recommended to the Petroleum Association that a cost of living bonus be given to the workers in view of the steep increases in prices but there was no unanimity, and the wages remained the same. Transportation to and from the oilfields was non-existent. Very often men had to walk distances from 5 to 8 miles to get home, not infrequently, at midnight. Those who wish to avoid travel could be accommodated only in the barrack dwellings that matched those of the sugar estates in dilapidation and lack of sanitation. Oil workers were subject to utter contempt by the white managerial staff a number of whom were recruited from South Africa, a country which had already become notorious for its treatment of non-white labour. Workers had no job security as they could be dismissed at a moment notice by their white bosses and may not obtain employment elsewhere because of "red booking".["Red Booking"- a system of recording workers‘ career and performance, which had to be produced by workers seeking employment: the person fired by one oil company was thus denied work in all other companies.] Governor in a dispatch to the Colonial Office said: ".....Labour has lived in conditions of extreme poverty and squalor, and the colour line has kept employer and employed at arm‘s length apart..." In another correspondence he said: "the wages of labour throughout the colony are admittedly too low, and abortive attempts have been made for years past to establish a minimum rate". The distressing conditions led to considerable destitution, especially in the urban centres. World events at this time also helped to create a greater race consciousness. Italian attacks on the Abyssinians did much to arouse anti-white feelings among the black population of Trinidad. According to one contemporary observer ‘the betrayal of Abyssinia is nearly as much to blame for the riots in Trinidad and Tobago as is the high cost of living‘. The labour disturbances which originated in the oilfields must be seen as the culmination of accumulated grievances of the labouring classes. Economic conditions such as low wages, rising prices and the unemployment and underemployment endemic in the island, were mainly responsible for the undercurrent of discontent in the country‘s working class. Although legitimate grievances existed among the workers of the two main industries there was no machinery for bringing them to the attention of the employers. All that was needed in these circumstances was a militant and daring leader, prepared to take personal risks in a mass confrontation with the ruling class in order to create an industrial crisis. Such a leader was now to emerge. He was Tubal Uriah Butler. These then were the conditions that fueled the labour riots and strikes from June 19th 1937 and give rise to organised labour. The Labour Strikes of June 1937 The Strike of oil workers was originally planed for June 22, but intelligence was received that the oil companies, the

http://www.bigwu.org Powered by Joomla! Generated: 21 June, 2012, 20:33

Banking, Insurance and General Workers Union

government and the police were concerting measures to frustrate it, as such the strike was brought forward to June 18th. The strike was intended to be peaceful and confined only to the oilfields, with workers simply sitting down on their jobs. The strike organizers warned the workers against street demonstrations, looting and forbade encouraging strikes in other industries. There was no strike fund, but the organizers had secured the assistance of the small businessmen within the oil belt. The strike began at midnight on June 18th, when rigmen sat down on the job at Trinidad Leaseholds Ltd, Forest Reserve and Fyzabad. The planners of the strike, like those who planned the general strike in Britain in 1926, did not anticipate the inexorable logic of a strike once it threatens the interests of the dominant elites and thus threatened would resort to the full use of the armed apparatus of the state whether the strikers intended to be peaceful or not. Warrants were issued for the arrest of Butler on charges of using violent language and of the incitement to breaches of the peace. Police were deplore in the oilfields and troops sent to the South. The Governor issued a proclamation prohibiting assemblies in the oil-producing counties of St. Patrick and Victoria. A party of policemen tried to arrest Butler, who at the time was addressing a large group of workers. The crowd exploded in anger, rush the police and rescued Butler. The crowd, cut the telephone lines, and turned their anger on the police. Some chase Corporal Charles King, who having fallen an broke his leg, was drenched with oil and burned to death. The police later regrouped and tried to recover the body of the slain policeman. But they were received with extreme hostility by the villagers who stoned and fired upon them. By the mourning of June 21st , what was initially a peaceful oil workers strike developed into an island-wide labour crisis. At Point Fortin bus-loads of men outside the district joined their counterparts and erected barriers across the road to prevent vehicles from entering the refinery. In San Fernando mob ruled the day. Sugar workers at the Usine St. Madeleine sugar estate invaded the bungalows of the white owners, smashed furniture and engaged in pilfering. the close down the unit that supplied water for domestic and sanitary purposes. On June 22nd, similar occurrences by sugar workers took place at Penal and Waterloo and Woodford Lodge estates. On June 22nd news of the unrest reach Port of Spain. Workers there, spurred on by activists of the NWCSA (Negro Welfare Cultural and Social Association) demonstrated through the city and closed down businesses. The workers even attempted to raid a train with a consignment of arms bound for San Fernando but the police opened fire and the raid was repulsed. On this day agricultural workers also strike and rioted in Rio Claro and Tabaquite. However, at Rio Claro the situation was worst as persons armed themselves and over-ran the railway station. The police were engage in battle and five men were killed and several injured. By June 23rd sugar workers on the Caroni sugar estate strike, so to did the workers on several estates on the outskirts of Arima: O‘Meara, Carapo, Esperanza, La Reunion, San Raphael and Golden Grove. Workers at the government owned St. Augustine estate also took strike action. By June 23rd workers on the Port of Spain waterfront, as well as workers employed by the City Council were on strike. Strikes in the Government‘s Public Workers Department had also spread rapidly, affecting thirty-one areas. By June 25th workers were on strike at the Bamboo Factory, St. Joseph, and on Black estate in Flanagin Town while in Tableland schools and post offices were forcibly closed. By June 26th the strike movement reached Mayaro, affecting the Beaumont, St. Anns and Lagoon Doux estates. By June 27th the agricultural workers at Caigual and Fishing Pond, on the Non Pariel and St. Lawrence estates also strike, and by June 29th workers attached to the Manzanilla Local Road Board also took strike action and in Tobago workers went on strike in sympathy with the Trinidad workers. Meanwhile the Governor proposed new rates of 72 cents for men and 60 cents for women in Port of Spain, outside of Port of Spain: men to receive 60 cents and women 36 cents, the purpose being to give the workers ‘a lead in the direction of wage increases‘ and the oil companies agree to raise the minimum wage per day from 56 cents to 72 cents and the working week to go down from 54 hours to 45 hours. By July 2nd Governor Fletcher now triumphantly reports to the Colonial Office: with the cordial agreement of the legislative council, I have ....set the minimum wage only a fraction higher than that of pre-depression years. Having seized the initiative with token increases and promises the Governor backed with the armed forces brought and end to the island-wide strike movement that had griped the country for the past month. The strikes of June 1937 had cut across the barriers of race within the working class population and affected every major sector of the economy. 100 years from 1837 Emancipation (1834) brought great fear to the ruling class. There was great worry as to whether the black population would accommodate to the system of free labour that was to be introduced. The general social system in Trinidad and Tobago was in some respects identical with the system then obtaining in the United Kingdom. In the 1830s in the UK trade unions had not been fully establish. Indeed they were fighting for recognition and encountering fierce resistance, opposition and even persecution. It was only in the latter half of the 19th century that the legislative and institutional framework was attaining that stage of development which would enable a free labour movement to emerge. So that the framework into which free labour in Trinidad and Tobago was introduced was the archaic legislation still obtaining in the ‘Mother Country‘

http://www.bigwu.org Powered by Joomla! Generated: 21 June, 2012, 20:33

Banking, Insurance and General Workers Union

1937 The first half of the 1930s witnessed the steady deterioration of working class living conditions in the main sectors of the Trinidad economy. By the early months of 1937 the purchasing power of the Trinidad and Tobago dollar had fallen drastically and was worth 70% of its 1929 value The two main sectors of the agricultural economy, sugar and cocoa, had remained depressed since the drop in world prices in the early 1920s. An adult male sugar or cocoa worker earned, at best, 40 cents per day. But it was in the oil industry, where substantial profits were being realized by oil companies, that working class resentments were first translated into strike action. By June 1937, Tubal Uriah Butler had emerged as the leading spokesman for the oil workers. On June 19th 1937 the oilfield workers struck and this was translated into a series of spontaneous strikes on the sugar and cocoa plantations and other sectors in almost every part of Trinidad and Tobago. The strike movement had cut across the barriers of race within the working class population and affected every major sector of the economy. Collective Bargaining In July 25th 1937 a committee of oil workers decided to publicly announce their intention to for a union and to conduct negotiations via the process of collective bargaining. Such an announcement was anathema to the oil companies, who were completely opposed to the unionization of workers and the principles of collective bargaining. However, by the end of 1937 six unions had gained official recognition from the colonial government. They were the Oilfield Workers Trade Union, All Trinidad Sugar Estates and Factory Workers Trade Union, Federated Workers Trade Union, Seamen and Waterfront Workers Trade Union, Public Works Workers Trade Union and the Amalgamated Building and Wood Workers Trade Union. The immediate net result of the 1937 general strike movement, therefore, was the achievement of the legal right to collective bargaining by workers. Today June 19 is Labour Day and is a public holiday in Trinidad and Tobago.

http://www.bigwu.org

Powered by Joomla!

Generated: 21 June, 2012, 20:33

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Implications of Educational Attainment To The Unemployment Rate Through Period of Time in The PhilippinesDokument34 SeitenThe Implications of Educational Attainment To The Unemployment Rate Through Period of Time in The PhilippinesStephRecato100% (3)

- Subject: SETTLEMENT OF HDFC Bank Credit Card # xxxxxxxxxxxx8614 Alternate Account Number (AAN) 0001014550008058618Dokument3 SeitenSubject: SETTLEMENT OF HDFC Bank Credit Card # xxxxxxxxxxxx8614 Alternate Account Number (AAN) 0001014550008058618Noble InfoTechNoch keine Bewertungen

- Out of Many AP Edition Chapter 24Dokument42 SeitenOut of Many AP Edition Chapter 24kae ayako100% (2)

- Bench Case StudyDokument2 SeitenBench Case StudyTeresita Urbano50% (4)

- Theme9 History NotesDokument12 SeitenTheme9 History NotesJM Mondesir67% (12)

- Adjustments To Emancipation 1838 - 1876Dokument19 SeitenAdjustments To Emancipation 1838 - 1876Shevon Robinson100% (2)

- Econometric Study On Malaysia's Palm Oil Position in TheDokument8 SeitenEconometric Study On Malaysia's Palm Oil Position in TheBagasNurWibowowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Connolly - The Rotten Heart of Europe The Dirty War For Europe's Money (1995)Dokument450 SeitenConnolly - The Rotten Heart of Europe The Dirty War For Europe's Money (1995)sumeets29100% (5)

- Labour Rebellions in The CaribbeanDokument10 SeitenLabour Rebellions in The CaribbeanAlicia GellizeauNoch keine Bewertungen

- British Industrialization in EnglandDokument39 SeitenBritish Industrialization in EnglandLene Angel MarshallNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dewind PeasantsMinersBackground 1975Dokument30 SeitenDewind PeasantsMinersBackground 1975chemo1987Noch keine Bewertungen

- History SbaDokument4 SeitenHistory SbaDanielleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Danna Gabriela Martinez Vargas - BANANA MASSACRE READINGDokument2 SeitenDanna Gabriela Martinez Vargas - BANANA MASSACRE READINGJuan Martinez VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Popular Protest in The 1980sDokument15 SeitenPopular Protest in The 1980syanique mooreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment Accounting BusinessDokument6 SeitenAssignment Accounting Businessalysanajla04Noch keine Bewertungen

- Revolució Petroli EngDokument24 SeitenRevolució Petroli EngBarri La SangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coal Strike of 1902Dokument5 SeitenCoal Strike of 1902RDrake666Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1930s Riots in The British West Indies PDFDokument52 Seiten1930s Riots in The British West Indies PDFWilliam Hunter100% (1)

- Concordant With Church But Church Interfernce in National and Political Matters RestrictedDokument13 SeitenConcordant With Church But Church Interfernce in National and Political Matters RestrictedAnimesh SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 3 HistoryDokument9 SeitenCH 3 HistoryirfaanffgamingNoch keine Bewertungen

- The General Strike and Coal Dispute of 1926 With Particular Reference To Ilkeston, DerbyshireDokument68 SeitenThe General Strike and Coal Dispute of 1926 With Particular Reference To Ilkeston, DerbyshireLubbertus22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Great Depression Notes3Dokument19 SeitenGreat Depression Notes3api-284455561Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Miners StrikesDokument6 SeitenThe Miners StrikesPeter MarshallNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Caribbean's Stolen Jewel: Andy GreenDokument3 SeitenThe Caribbean's Stolen Jewel: Andy GreenKML1992Noch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Of "Employer-Military Complicity During Last Military Dictatorship In Argentina" By Victoria Basualdo: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESVon EverandSummary Of "Employer-Military Complicity During Last Military Dictatorship In Argentina" By Victoria Basualdo: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development of TUDokument51 SeitenDevelopment of TUMasterchef Sugars BillouinNoch keine Bewertungen

- East Anglian RiotsDokument13 SeitenEast Anglian RiotsDafydd Robert HumphreysNoch keine Bewertungen

- NTSE The Making of A Global WorldDokument4 SeitenNTSE The Making of A Global Worldvidushi1121Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading 9: Corporate Imperialism in The PhilippinesDokument11 SeitenReading 9: Corporate Imperialism in The PhilippinesynaNoch keine Bewertungen

- APUSH - LAbor in The Gilded AgeDokument6 SeitenAPUSH - LAbor in The Gilded AgeAndrew MuccioloNoch keine Bewertungen

- D) Development of A PeasantryDokument7 SeitenD) Development of A PeasantryArif MohamedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workers Vanguard No 34 - 7 December 1973Dokument12 SeitenWorkers Vanguard No 34 - 7 December 1973Workers VanguardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of The Industrial RevolutionDokument8 SeitenEffects of The Industrial RevolutionShabnam BarshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MiningDokument6 SeitenMiningARIES C. BULLONoch keine Bewertungen

- MDP 39015034112782 577 1638942222Dokument1 SeiteMDP 39015034112782 577 1638942222Jorge SuárezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guyana's Golden AgeDokument20 SeitenGuyana's Golden AgePro GuyanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1914 Ludlow MassacreDokument3 Seiten1914 Ludlow MassacreMark StrifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guatemala Economy Environment EssayDokument14 SeitenGuatemala Economy Environment Essayapi-253633137Noch keine Bewertungen

- CBSE Class 10 History Chapter 3 Notes - The Making of A Global WorldDokument9 SeitenCBSE Class 10 History Chapter 3 Notes - The Making of A Global Worldmanoj trivediNoch keine Bewertungen

- THEME 5 Adjustments To Emancipation Complete With ObjectivesDokument12 SeitenTHEME 5 Adjustments To Emancipation Complete With ObjectivesJacob seraphine100% (1)

- NCERT Q/A Global World Class 10thDokument5 SeitenNCERT Q/A Global World Class 10thAditya MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presented By: Binny Talati Sneha MorabDokument24 SeitenPresented By: Binny Talati Sneha MorabBinny TalatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workers Vanguard No 501 - 04 May 1990Dokument12 SeitenWorkers Vanguard No 501 - 04 May 1990Workers VanguardNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 HisDokument25 Seiten10 HisVishal dandeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historynotes Theme8Dokument11 SeitenHistorynotes Theme8JM Mondesir86% (7)

- Industrial RevolutionDokument4 SeitenIndustrial RevolutionTracey-Lee LazarusNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Depression: Study: Assignment No: Date: TeacherDokument4 SeitenThe Great Depression: Study: Assignment No: Date: TeacherAhmed Ullah ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curse of The Black GoldDokument11 SeitenCurse of The Black Goldhst939Noch keine Bewertungen

- BBA 3001 Global Business CourseworkDokument4 SeitenBBA 3001 Global Business CourseworkChaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labour Rebellions of The 1930s in The British Caribbean Region Colonies - Readings - 214d4Dokument21 SeitenLabour Rebellions of The 1930s in The British Caribbean Region Colonies - Readings - 214d4Lameka MelbourneNoch keine Bewertungen

- G. Heuman 1865: Prologue To The Morant Bay Rebellion in JamaicaDokument94 SeitenG. Heuman 1865: Prologue To The Morant Bay Rebellion in JamaicajasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- LeGrand LaborDokument24 SeitenLeGrand LaborrappapojNoch keine Bewertungen

- The British Economy in The 19 and Early 20 Century 1. The Rise To Economic SupremacyDokument3 SeitenThe British Economy in The 19 and Early 20 Century 1. The Rise To Economic SupremacyFlori StoianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Industrial RevolutionDokument6 SeitenThe Industrial Revolutionapi-252747198Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Depression - Part2Dokument19 SeitenThe Great Depression - Part2philipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- International: Published by The West Midlands International Forum Summer 2014Dokument8 SeitenInternational: Published by The West Midlands International Forum Summer 2014Dave AugerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2p Portefolio Crash29Dokument3 Seiten2p Portefolio Crash29Sofia McVeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class Struggle 107Dokument16 SeitenClass Struggle 107davebrownzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catherine Legrand - Labor Acquisition and Social Conflict On The Colombian FrontierDokument24 SeitenCatherine Legrand - Labor Acquisition and Social Conflict On The Colombian FrontierSebastián Londoño MéndezNoch keine Bewertungen

- THEME 6 Caribbean EconomydocxDokument15 SeitenTHEME 6 Caribbean EconomydocxJacob seraphineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Marketing ReportDokument13 SeitenBusiness Marketing ReportInfokeedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 IndustrializationDokument40 SeitenChapter 4 Industrializationapi-241427002100% (1)

- The Making of A Global World: I) The Pre-Modern World # Silk Routes Link The WorldDokument5 SeitenThe Making of A Global World: I) The Pre-Modern World # Silk Routes Link The Worldalok nayakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eclectica Agriculture Fund Feb 2015Dokument2 SeitenEclectica Agriculture Fund Feb 2015CanadianValueNoch keine Bewertungen

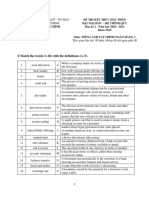

- Đề thi tiếng Anh chuyên ngành Tài chính Ngân hàng 1Dokument4 SeitenĐề thi tiếng Anh chuyên ngành Tài chính Ngân hàng 1Hoang TrieuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sop PDFDokument15 SeitenSop PDFpolikopil0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Phase 1 Course RecognitionDokument6 SeitenPhase 1 Course Recognitionnicolas rodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship 11/12 First: Learning Area Grade Level Quarter DateDokument4 SeitenEntrepreneurship 11/12 First: Learning Area Grade Level Quarter DateDivine Mermal0% (1)

- EXEC 870-3 e - Reader - 2016Dokument246 SeitenEXEC 870-3 e - Reader - 2016Alexandr DyadenkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fractional Share FormulaDokument1 SeiteFractional Share FormulainboxnewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Becg m-4Dokument25 SeitenBecg m-4CH ANIL VARMANoch keine Bewertungen

- Nicolas - 8 - 1Dokument10 SeitenNicolas - 8 - 1Rogelio GoniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Private Equity AsiaDokument12 SeitenPrivate Equity AsiaGiovanni Graziano100% (1)

- Sahil Tiwari Personality Develpoment Assignment PDFDokument5 SeitenSahil Tiwari Personality Develpoment Assignment PDFsahiltiwari0777Noch keine Bewertungen

- AU Small Finance Bank - Research InsightDokument6 SeitenAU Small Finance Bank - Research InsightDickson KulluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microeconomics PS #1Dokument2 SeitenMicroeconomics PS #1Kanav AyriNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSR STPDokument7 SeitenCSR STPRavi Shonam KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 ReviseDokument4 SeitenChapter 2 ReviseFroy Joe Laroga Barrera IINoch keine Bewertungen

- All ZtcodeDokument4 SeitenAll Ztcodetamal.me1962100% (1)

- Invoice 41071Dokument2 SeitenInvoice 41071Zinhle MpofuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standard & Poors Outlook On GreeceDokument10 SeitenStandard & Poors Outlook On GreeceEuronews Digital PlatformsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strama Quiz 8Dokument2 SeitenStrama Quiz 8Yi ZaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Lanka - MAS Holdings Enters New Venture With BAM KnittingDokument2 SeitenSri Lanka - MAS Holdings Enters New Venture With BAM KnittingsandamaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ans: Q2 Moon Manufacturing Company (Dec31, 2017) : Cost of Goods Manufactured StatementDokument3 SeitenAns: Q2 Moon Manufacturing Company (Dec31, 2017) : Cost of Goods Manufactured StatementAsma HatamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multi-Dimensions of Unit Linked Insurance Plan Among Various Investment AvenuesDokument8 SeitenMulti-Dimensions of Unit Linked Insurance Plan Among Various Investment AvenuesRahul TangadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal Dan JWBN Siklus DGGDokument17 SeitenSoal Dan JWBN Siklus DGGGhina Risty RihhadatulaisyNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 190506 Coral Bay Nickel Corporation, Petitioner, Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. Decision Bersamin, J.Dokument3 SeitenG.R. No. 190506 Coral Bay Nickel Corporation, Petitioner, Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. Decision Bersamin, J.carlo_tabangcuraNoch keine Bewertungen