Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

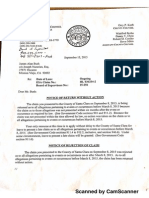

Legal Research On Landlord-Tenant Suit

Hochgeladen von

James Alan BushOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Legal Research On Landlord-Tenant Suit

Hochgeladen von

James Alan BushCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

Duty of landlord to protect tenant from criminal acts of third party. The general duty of maintenance of leased premises includes the duty to take reasonable steps to secure common areas against the foreseeable criminals acts of third parties that would likely occur in the absence of such precautionary measures. [Ann M. v. Pacic Plaza Shopping Center (1993) 6 Cal 4th 666, 674, 25 Cal. Rptr. 2D 137, 863 P2d 207; Frances T. v. Village Green Owners Assn. (1986) 42 Cal 3d 490, 229 Cal Rptr 456, 723 P2d 573, 59 ALR4th 447 (defendant was condominium association that was, for all practical purposes, condominium project's landlord)] In one case, for example, a tenant of an apartment building was assaulted by two intruders who were waiting in the common hallway of the premises. In nding that the tenant stated a cause of action against the landlords for negligence, the court noted that the landlords were aware of crimes in the apartment building and in specic apartments caused by the condition of the premises. Additionally, the landlords were aware of tenant reports of crime on the premises and of complaints concerning conditions that permitted free access to the premises and permitted criminal activity on the premises.[Penner v. Falk (1984, 2nd Dist) 153 Cal App 3d 858, 200 Cal Rptr 661] Similarly, a tenant who was raped in her apartment stated a cause of action against the landlords for failure to warn of the danger of rape or to provide adequate security where the landlords allegedly knew of past assaults and of conditions making future attacks likely. [O'Hara v. Western Seven Trees Corp. (1977, 1st Dist) 75 Cal App 3d 798, 142 Cal Rptr 487; see Kwaitkowski v. Superior Trading Co. (1981, 1st Dist) 123 Cal App 3d 324, 176 Cal Rptr 494 (tenant who was assaulted, battered, raped, and robbed in lobby of apartment building stated cause of action against landlords where landlords had prior notice that tenant was assaulted and robbed 2 months earlier, that their building was in high crime area, and that lock of lobby entrance door was defective)] When a landlord has no knowledge of prior criminal acts or conditions, the landlord's duty to warn or protect will not be found. [See, for example, Davis v. Gomez (1989, 2nd Dist) 207 Cal App 3d 1401, 255 Cal Rptr 743 (landlord's failure to evict psychotically behaving tenant not proximate cause of fatal shooting by that tenant absent landlord's knowledge of or duty to investigate prior shooting by tenant); for discussion of facts of Davis in context of nuisance, see Nuisance] In addition, a tenant's negligence action against her landlord for injuries resulting from the criminal assault of a third person must be supported by evidence establishing that it was more probable than not that, but for the landlord's negligence, the assault would not have occurred. Where there is evidence that an assault could have occurred even in the absence of a landlord's negligence, proof of causation cannot be based on mere speculation, conjecture, and inferences drawn from other inferences to reach a conclusion unsupported by any real evidence, or on an expert's opinion based on inferences, speculation, and conjecture. Furthermore, where there is no factual basis for an expert's opinion or for the plaintiff's assertion of causation, the conclusion is unavoidable that summary judgment was properly granted. [Leslie G. v. Perry & Associates (1966) 43 Cal.App.4th 472, 50 Ca.Rptr.2d 785 (afrming summary judgment against tenant raped in underground security parking facility who failed to prove that broken gate was way in which perpetrator entered garage area)] Under reghter's rule, an apartment owner owed no duty to protect a deputy sheriff from a danger when he was employed to confront even though the injury occurred at plaintiff's place of residence. Plaintiff, an off-duty deputy sheriff, alleged that defendant's failure to correct known security and maintenance problems caused his injuries when he confronted and ultimately shot and killed a suspected burglar in the apartment building where he lived. The court found that, plaintiff acted in response to suspected criminal activity he acted as a California peace ofce,r utilizing his professional training; he asserted his authority as a

Page 1 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

California peace ofcer and he exercised his statuary authority to use force, including deadly force. These activities were inherently part of plaintiff's job and were the types of hazards plaintiff had been trained and employed to confront. [Hodges v. Yarian (1997) 53 Cal.App.4th 973, 62 Cal.Rptr.2d 130] Civil Code 847 grants immunity from liability to a possessory or nonpossessory property owner who causes injury or death to a perpetrator of a felony specied in Civ. Code 847(a) on the owner's property. However, Civ. Code 847 does not so limit the liability of a property owner or owner's agent for willful, wanton, or criminal conduct or for willful or malicious failure to guard or warn against a dangerous condition, use, structure or activity on the property. [Cavillo-Silva v. Home Grocery (1998) 19 Cal.4th 714, 80 Cal.Rptr.2d 506, 968 P. 2d 65 (appellate court reversed trial court's summary judgment granted to robber-plaintiff in suit against property owner who shot him back as he was exiting store in robbery attempt on basis of conicting evidence)] In Sharon P. v. Arman, Ltd. (1999) 21 Cal.4th 1181, 91 Cal.Rptr.2d 35, 989 P.2d 121, cert. den. (U.S. 2000) 120 S.Ct. 2689, 147 L.Ed.2d 961, a case brought by a woman who was attacked and sexually assaulted at gunpoint in a subterranean garage of a commercial ofce building where she worked, the appellate court afrmed the defendants' summary judgment. The trial court found that a sexual assault by a third party in the garage is not sufciently foreseeable to support a requirement that defendants secure that area against such crime. Prior bank robberies on the ground oor of the building were not sufciently similar to the sexual assault to establish a high degree of forgeability that would impose an obligation to provide security guards in the garage. The appellate court further state that, "Commercial underground parking structures are not 'inherently dangerous' and crime highly foreseeable as a matter of law." This would place an unfair burden on landlords, who, in effect, would be forced to become the insurers of public safety, contrary to well established policy in this state. In addition, absent any prior similar incidents indicating a foreseeable risk of violent criminal assaults around the garage, defendants were not required to provide lighting, security cameras, or walk-throughs by guards to secure the area. Also see Nicole M. v. Sears, Roebuck & Co. (1999) 76 Cal.App.4th 1238, 90 Cal.Rptr.2d 922, where a woman who was the victim of a sexual assault in an outdoor department store parking lot brought a negligence action against the department store. The store manager was aware that a homeless man had been camping for eight months in bushes near the location where plaintiff was attacked, bu the homeless man was not plaintiff's attacker. There was no prior record of a sexual assault at that shopping center. The appellate court afrmed the trial court summary judgment for defendant. Low lighting, overgrown bushes, and the presence of the homeless person did not make the property inherently dangerous. These circumstances were not cause for the property owner to reasonably anticipate crime in the absence of prior similar incidents. The mere possibility of causation in negligence actions is not enough. The liability of apartment owners and other business enterprises to persons injured on their premises by the criminal acts of others, is a liability based solely on the business owner's negligent failure to provide adequate security measures to protect those who enter their property. There is a need to balance two important and competing policy concerns: society's interest in compensating persons injured by another's negligent acts and reluctance to impose nancial burdens on property owners. Plaintiff was an employee of Federal Express. Defendants were owners of the Sherwood Apartments, a complex located in Bellower. Plaintiff came to the comp less to deliver a package to a resident. As she entered through one of the many-gated entrances to the premises, she saw three young men loitering outside a security gate that had been propped open. The three of them beat her and attempted to rape her, inicting serious injuries. Her assailants ed and were never apprehended. Since plaintiff could not prove the identity of

Page 2 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

her assailants, she was unable to show that her assailants were unauthorized to enter the premises or whether unlocked gates were a substantial factor in causing her injuries, and there was no proper basis for shifting the burden of proof to defendants. Saelzler v. Advanced Group 400, 25 Cal. 4th 763, 107 Cal. Rptr. 2d 617, 23 P.3d 1143 (2001). Foreseeability Foreseeability has been at the heart of the discussion concerning landlord liability for the criminal cts of third parties. Formerly, some courts applied a rigid test of foreseeability to determine the landlord's liability. For example, in Riley v. Marcus (1981, 2nd Dist) 125 Cal App 3d 103, 177 Cal Rptr 827, the court held that tenant who was raped in her apartment failed to state a cause of action against her landlord where there was no history of rapes or similar acts of violence on the premises. However, cases like Riley are now legally questionable in light of the California Supreme Court's explicit rejection of the rigidied foreseeability concept applied in Riley. [Frances T. v. Village Green Owners Assn. (1986) 42 Cal 3d 490, 229 Cal Rptr 456, 723 P2d 573, 59 ALR4th 447 (referring to Isaacs v. Huntington Memorial Hospital (1985) 38 Cal 3d 112, 211 Cal Rptr 356, 695 P2d 653)] Specically, in Isaacs the court held that foreseeability does not require prior identical or even similar acts, and that foreseeability is but one factor to be weighed along with the "totality of circumstances" in determining whether a landowner owes a duty in a particular case. In Ann M. v. Pacic Plaza Shopping Center (1993) 6 Cal 4th 666, 25 Cal Rptr 2d 137, 863 P2d 207, the California Supreme Court, recognizing the confusion surrounding Isaacs, claried and elaborate on the role of foreseeability in the landlord's duty to the tenant. The court noted that before and after Isaacs, the court recognized that the scope of the landlord's duty is determined in part by balancing the foreseeability of the harm against the burden of the duty to be imposed. If there are strong policy reasons for preventing the harm, or if the harm can be prevented by simple means, a lesser degree of foreseeability is required. The greater the burden of preventing the harm, the higher the degree of foreseeability that is required. Duty in such circumstances is determined by a balancing of foreseeability of the criminal acts against the burdensomeness, vagueness, and efcacy of the proposed security measures. [Ann M. v. Pacic Plaza Shopping Center (1993) 6 Cal 4th 666, 678-679, 25 Cal Rptr 2d 137, 863 P2d 207 (quoting Gomez v. Ticor (1993, 2nd Dist) 145 Cal App 3d 622, 631, 193 Cal Rptr 600)] In Ann M., an employee of a commercial tenant was raped on the leased premises during business hours. The plaintiff argued that the landlord was negligent in not providing security guards for the premises. The court, in holding for the landlord, noted the "not insignicant" costs to the landlord in supplying security guards and stated that a high degree of foreseeability was required in order to nd that ht escape of a landlord's duty of care includes the hiring of security guards. The court found that there was no evidence that the landlord had any notice of prior criminal activity on the premises. To the contrary, the court found that the landlord had a standard practice of noting or recording instances of violent crime, and that the records contained no reference to violent criminal acts prior to the rape of the plaintiff. The court held that the requisite degree of foreseeability rarely, if ever, can be proven in the absence of prior similar incidents of violent crime on the landowner's premises. To hold otherwise concluded the court, would be to impose an unfair burden upon landlords and, in effects would force landlords to become the insurers of public safety. The duty to take steps to prevent the wrongful acts of a third person will be imposed only where such conduct can be reasonably anticipated. Foreseeability is a question of law for the court to decide. [Jefferson v. Qwik Korner Market, Inc. (1994, 4th Dist.) 28 Cal.App.4th 990, 34 Cal.Rptr.2d 171 (car jumping curb outside defendant's convenience store was not foreseeable)] Thus, for example, in a suit against a landlord and condominium association by a plaintiff who had been sexually assaulted on the leased premises, the court held that the rape

Page 3 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

was not foreseeable to the degree that it imposed a duty on defendants to protect plaintiff from the criminals acts of third parties, since the defendants had no notice of prior similar incidents on the premises. [See Pamela W. v. Millson (1994, 4th Dist.) 25 Cal.App.4th 950, 30 Cal.Rptr. 2d 690] The focus of the Ann M. analysis [see Ann. M. v. Pacic Plaza Shopping Center (1993) 6 Cal.4th 666, 25 Cal.Rptr.2d 137, 863 P.2d 207] is whether there were prior similar incidents that would create a high level of foreseeability. In looking at the question of foreseeability the task is not to decide whether a particular plaintiff's injury was reasonably foreseeable in light of a particular defendant's conduct, or the precise nature of the physical injury that results, but rather to evaluate more generally whether the category of negligent conduct at issue is sufciently likely to result in the kind of harm experience that liability may appropriately be imposed on the negligent party. [Leslie G. v. Perry & Associates (1996) 43 Cal.App.4th 472, 50 Cal.Rptr.2d 785; see Robison v. Six Flags Theme Parks Inc. (1998) 64 Cal.App.4th 1294, 75 Cal.Rptr.2d 838 (in negligence action, lack of prior similar incidents is not proper basis for summary judgment; conduct is negligent if unreasonable risk of danger to others would have been foreseen by reasonable person)] Plaintiffs seeking to establish landlord liability for criminal acts of third parties are cautioned that trial courts may dene "prior similar incidents" so narrowly that they are inevitable unforeseeable. In Ann M., where the victim was raped in the course of a store robbery, the Supreme Court characterized the duty inquiry as whether "violent criminal assaults" were foreseeable. [See Ann M. v. Pacic Plaza Shopping Center (1993) 6 Cal.4th 666, 25 Cal.Rptr.2d 137, 863 P.2d 207] In another case, a landlord was held not liable for an intoxicated tenant's accidental shooting of a guest. Though the plaintiff offered evidence showing that the landlord knew the tenant, the landlord's son, had an alcohol problem and kept rearms in the rented premises, the plaintiff failed to offer evidence showing that those two factors created a dangerous condition for guests. The plaintiff offered no evidence that the tenant ever harmed anyone because of his alcohol problem or that he handled rearms in an unsafe manner while intoxicated. In concluding that the plaintiff's injury was not reasonably foreseeable, the court held that a landlord's knowledge that a tenant misuses alcohol and possesses rearms does not put the landlord on notice that he or she needs to protect visitors from injury in the absence of evidence of knowledge chargeable to the landlord that the tenant has violent tendencies or handles rearms in an unsafe manner while drinking. [Sturgeon v. Curnutt (1994, 3rd Dist.) 29 Cal.App.4th 301, 34 Cal.Rptr.2d 498] Under the reghter's rule, an apartment owner owed no duty to protect a deputy sheriff from a danger he was employed to confront even though the injury occurred at plaintiff's place of residence. Plaintiff, an off-duty deputy sheriff, alleged that defendant's failure to correct known security and maintenance problems caused his injuries when he confronted and ultimately shot and killed a suspected burglar in the portent building where he lived. The court found that, plaintiff acted in response to suspected criminal activity; he acted as a California peace ofcer, utilizing his professional training; he asserted his authority to use force, including deadly force. These activities were inherently part of plaintiff's job and were the types of hazards plaintiff had been trained and employed to confront. [Hodges v. Yarian (1997) 53 Cal.App.4th 973, 62 Cal.Rptr.2d 130] The mere possibility of causation or pure speculation or conjecture the mere possibility of causation in negligence actions is not enough. The liability of apartment owners and other business enterprises to persons injured on their premisses by the criminal acts of others, is a liability based solely on the business owners' negligent failure to provide adequate security measures to protect those who enter their property. There is a need to balance two important and competing policy concerns: society's interest in compensating persons injured by

Page 4 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

another's negligent acts and reluctance to impose nancial burdens on property owners. Plaintiff was an employee of Federal Express. Defendants were owners of the Sherwood Apartments, a complex located in Bellower. Plaintiff came to the complex to deliver a package to a resident. As she entered through one of the many-gated entrances to the premises, she saw three young men loitering outside a security gate that had been propped open. The three of them beat her and attempted to rape her, inicting serious injuries. Her assailants ed and were never apprehended. Since plaintiff could not prove the identity of her assailants, she was unable to show that her assailants war unauthorized to enter the premises or whether the unlocked gates were a substantial factor in causing her injuries, and there was no proper basis for shifting the burden of proof to defendants. Saelzler v. Advanced Group 400, 25 Cal. 4th 763, 107 Cal. Rptr. 2d 617, 23 P.3d 1143 (2001). The duty owed by an owner of an interest in real property must have a relationship to the degree of control conferred by the scope of the ownership interest itself. The appellate court held that the homeowner association members had no duty of care to prevent an individual property owner from allowing his dogs to escape and injure an 11 year old on a private road within a subdivision easement. The only [page 1233] connection to the harm alleged was their nonexclusive right to pass over the private streets. The association members were mere residents of the subdivision, and had no power to control the dog owner or his dogs. Each member possessed only a single vote on association affairs and did not make policy for the association Cody F. v. Falletti, 92 Cal. App. 1232, 112 Cal. Rptr. 2d 593 (1st Dist. 2001) Foreseeability of criminal acts by third parties is a question of law for the court. The requisite degree of foreseeability for violent crime rarely can be proven in the absence of prior similar incidents of violent crime on the landowner's premises. [Lopez v. Baca, 98 Cal. App. 4thg 1008, 120 Cal. Rptr. 2d 281 (2d Dist 2002), as modied, (June 5, 2002)] The appellate court stated that landowners owe a duty to tenants and invitees to maintain their premises in a reasonably safe condition. This duty encompasses a responsibility to take reasonable steps to secure the premiere against hazardous events lily to occur in the absence of such precautionary measures. In analyzing the existence and scope of a landowner's duty, the court must balance the foreseeability of the harm alleged against the burden of the duty to be imposedthe greater the burden of preventing the harm, the higher the degree of foreseeability required. Because the burden of employing private guards to protect against third-party criminal conduct is great, a high degree of foreseeability is required in order to nd that the score of a landlord's duty of care includes the hiring of security guards. A school district appealed judgment, arguing that it owned no duty of care to the special education junior high student to prevent sexual assault. The appellate court disagreed nding the school district owed the student a duty of care to protect him from a foreseeable assault and found that since the assault occurred on the school's watch, while the student was entrusted to the school's care the assault was substantially caused by the school's indifference toward the dangers posed by failing to adequately supervise its students, particularly special education students. The court found that a special relationship is formed between a school district and its students which results in the imposition of afrmative duty on the district to take all reasonable steps to protect its students; this afrmative duty arises, in part, based on the compulsory nature of education. [M.W. v. Panama Buena Vista Union School Dist., 1 Cal.Rptr.3d 673, 110 Cal.App.4th 508] Intentional iniction of emotional distress dened The recognition of peace of mind as a legally protected interest is a relatively recent development. It is only within recent years that courts have allowed damages for emotional upset without accompanying physical injury. [State Rubbish Collectors Asso. v. Siliznoff (1952) 38 Cal 2d 330, 240 P2d 282; Witkin, 5 Summary of California L., Torts 402 (9th ed.)]

Page 5 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

In order to successfully plead a cause of action for intentional iniction of emotional distress, the plaintiff must allege [Nally v. Grace Community Church (1988) 47 Cal 3d 278, 253 Cal Rptr 97, 763 P2d 948, cert den 490 US 1007, 104 L Ed 2d 159, 109 S Ct 1644; Saunders v. Cariss (1990, 4th Dist) 224 Cal App 3d 905, 274 Cal Rptr 186]: 1) outrageous conduct by the defendant; 2) an intention by the defendant to cause, or reckless disregard of the probability of causing, emotional distress; 3) severe emotional distress; and 4) an actual and proximate causal link between the tortious conduct and the emotional distress. Whether pleaded as an element of the prima facie case or as an afrmative defense, it must also appear that the defendant's conduct was not privileged. [Cote v. Henderson (1990, 2nd Dist) 218 Cal App 3d 796, 267 Cal Rptr 274] An action for intentional iniction of emotional distress is governed by the 1-year statue of limitations ordinarily applicable to personal injury claims. [Code Civ. Proc. 340(3)] The tort is complete, for statue of limitations purposes, when the effect of a defendant's conduct results in plaintiff's severe emotional distress. [Holliday v. Jones (1989, 4th Dist) 215 Cal App 3d 102, 264 Cal Rptr 448; for complete discussion of intentional iniction of emotional distress, see TORTS Intentional Iniction of Emotional Distress Ch 14] The Fair Employment and Housing Commission is authorized to award claimant actual damages, including damages for emotional distress. [Konig v. Fair Employment and Housing Com'n, 28 Cal. 4th 743, 123 Cal. Rptr. 2d 1, 50 P.3d 718 (2002)] In adjudicating a claim of housing discrimination based on race under the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) (Gov. Code, 12900 et seq.), the Fair Employment and Housing Commission awarded the prevailing claimant, a black woman, damages for emotional distress she suffered when the landlady of the rental unit told her she would not rent to her and slammed the door in her face. In mandate proceedings led by the landlady, the trial court partially granted the petition but struck the $10,000 awards for emotional distress and lost housing opportunity on the ground that the commission was constitutionally prohibited from awarding general compensatory damages for emotional distress. Landlord-tenant relations The right to recover for emotional distress without physical injury is recognized in situations involving extreme and outrageous conduct. There is liability for conduct exceeding all bounds usually tolerated by a decent society, of a nature that is especially calculated to cause, and does cause, mental distress. Behavior may be considered outrageous if a defendant abuses a relationship or position that gives him or her the power to damage the plaintiff's interest, knows the plaintiff is susceptible to injuries through mental distress, or acts intentionally or unreasonably with the recognition that the acts are likely to result in illness through mental distress. [Stoiber v. Honeychuck (1980, 5th Dist) 101 Cal App 3d 903, 921, 162 Cal Rptr 194; see also Intentional Iniction of Emotional Distress by Landlord, 46 Am. Jur. Proof of Facts 2d 429] Severe emotional distress means emotional distress of such substantial quantity or enduring quality that no reasonable person in a civilized society should be expected to endure it, and may consist of any highly unpleasant mental reaction such as fright, grief, shame, humiliation, embarrassment, anger, chagrin, disappointment or worry. [Newby v. Alto Riveria Apartments (1976, 1st Dist) 60 Cal App 3d 288, 298, 131 Cal Rptr 547] In addition to being extreme and outrageous, and causing severe emotional distress, it is imperative that the conduct be not privileged or an act sanctioned by law. The actor is never

Page 6 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

liable where he or she has done no more than to insist on his or her legal rights in a permissible way, even though he or she is well aware that such insistence is certain to cause emotional distress. [Restatement 2d, Torts 46 comment g] Allegations found sufcient to state a cause of action for intentional iniction of emotional distress have been found in the following: 1) a tenant, in addition to pursuing actions based on breach of warranty of habitability and nuisance, alleged that the landlord's failure to correct the defective conditions of the premises was knowing, intentional and willful, and that she suffered extreme emotional distress resulting from the condition of the premises. The conditions alleged, supported by a county health department notice to vacate and demolish the premises, included have cockroach infestation, broken interior walls, broken deteriorated ooring, falling ceiling, deteriorated, overused electrical wiring, lack of proper plumbing connections to the sewage system in the bathroom, sewage under the bathroom oor, leaking roof, broken windows, and re hazard. [Stoiber v. Honeychuck (1980, 5th Dist) 101 Cal App 3d 903, 912, 162 Cal Rptr 194] 2) a tenant presented substantial evidence that the landlords' behavior was outrageous in that the landlords acted knowingly and unreasonably with the intention to inict mental distress, and abused the special relationship between landlords and tenants. The tenant organized a meeting of the tenants to petition the owners to discuss announced rent increases. The manager told the tenant that she was a troublemaker, shouted at her, and ordered her out of the apartment in three days. Another tenant testied that the manager said he would throw the tenant out personally if she did not leave. Another defendant threatened the tenant when he said, "We are going to handle this the way we do down South." When the tenant explained to this defendant that she was not going to vacate her apartment, he said, "Do you want to bet your life?" The court noted that the defendants' continuous harassment and intimidation of the tenant was intended to cause fear and worry and was not a mere insult or annoyance. This total course of conduct, held the court, met the test of outrageous conduct. [Newby v. Alto Riveria Apartments (1976, 1st Dist) 60 Cal App 3d 288, 131 Cal Rptr 547] 3) A damage award was afrmed where the tenant established that during her pregnancy and while she was absent from her apartment, for which the current rent had been paid, the defendant manager removed her possessions to the basement, rented the apartment to others, and prevented her form suing an elevator to remove her possessions. She made several trips to carry the possessions to the street, became emotionally and physically upset, and subsequently suffered a miscarriage. The court held that the defendants intentionally and unreasonably subjected the plaintiff to severe mental stress and physical strain resulting in physical injury and mental suffering to the plaintiff. [richardson v. Pridmore (1950) 97 Cal App 2d 124, 217 P2d 113, 17 ALR2d 929; see also Emden v. Vitz (1948) 88 Cal App 2d 313, 198 P2d 696 (tenant recovered for mental suffering and physical harm where she was locked out of her apartment and subjected to verbal abuse by landlord, which caused various physical ailments including exacerbation of glandular condition)] 4) a cause of action for emotional distress was stated in a complaint alleging that, among other things, the reasonable rental value of the apartment occupied by the plaintiffs was $75 per month, that shortly after the plaintiffs informed the defendant-landlord of their intent to make certain repairs and deduct the cost from the rent, pursuant to Civ. Code 1941, 1942, the defendant raised the rent to $145, that such gure was unfair, unreasonable and uneconomical, that defendant knew plaintiffs could not pay that amount, and that, therefore, the raise constituted an actual eviction. [Aweeka v. Bonds (1971, 1st Dist) 20 Cal App 3d 278, 97 Cal Rptr 650]

Page 7 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

Practice Note: Sexual harassment by the landlord-owner or the manager creates a hostile environment and is a form of sex discrimination prohibited by FHA and FEHA. [Brown v. Smith (1997) 55 Cal.App.4th 767, 787, 64 Cal.Rptr.2d 301 (creating liability under Civ. Code 51.9 (Unruh Act))] A single instance of harassment may be sufcient to establish an employer's liability, bu touch an incident must be severe in the extreme and generally must include either physical violence or the threat thereof. [Herberg v. California Institute of the Arts, 101 Cal. App. 4th 142, 124 Cal. Rptr. 2d 1, 168 Ed. Law Rep. 420, 89 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1025 (2d Dist. 2002), review denied, (Nov. 13, 2002)] In this case, none of the plaintiffs were physically touched or subjected to any sort of verbal abuse but depicted in two students' vulgar and sexually explicit drawing that was displayed in a student exhibition in the main gallery institute for about 24 hours. It held that the alleged harassment was not sufciently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of plaintiffs' employment and create a hostile work environment within the meaning of the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (Gov. Code, 12900 et seq.). Also, the drawing was not intended to harass plaintiffs, rather to make a point about representational art. Nuisance Nuisance liability is not precluded by the existence of a contractual relationship between the tenant and the landlord. An act that constitutes a breach of contract may also be tortious. [Stoiber v. Honeychuck (1980, 5th Dist) 101 Cal App 3d 903, 162 Cal Rptr 194] Every person is bound without contract to abstain from injuring the person or property of another, or infringing upon any of his rights. [Jones v. Kelly (1929) 208 Cal 251, 255, 280 P 942] Regardless of whether the occupant of land has sustained physical injury, he or she may recover damages for the discomfort, annoyance, and mental suffering occasioned by fear for the occupant's own safety and that of his or her family when such discomfort or suffering has been proximately caused by a trespass or a nuisance. [Acadia, California, Ltd. v. Herbert (1960) 54 Cal 2d 328, 337, 5 Cal Rptr 686, 353 P2d 294] In Stoiber, the court held that the tenant stated a cause of action for nuisance by alleging facts showing a substantial interference with the use and enjoyment of the premisesnot merely a de minimis interference. The court found that the tenant pleaded sufcient facts to support her prayer for exemplary damages. She alleged that the landlords had actual knowledge of defective conditions in the premises including leaking sewage, deteriorated ooring, falling ceiling, leaking roof, broken windows, and other unsafe and dangerous conditions. She further alleged that the landlords, in maintaining these nuisances, acted with full knowledge of the consequences of their actions and the damage being caused to the tenant, and that the landlords' conduct was willful, oppressive and malicious. [Stoiber v. Honeychuck (1980, 5th Dist) 101 Cal App 3d 903, 162 Cal Rptr 194] Nuisance actions, however, are not limited to the conditions of the premises, but may be based on the actions of or conditions created by other tenants. For example, in Davis v. Gomez (1989, 2nd Dist) 207 Cal App 3d 1401, 255 Cal Rptr 743, one tenant was shot and killed by another tenant. Although the landlord was found not liable for the death of the tenant, the court mentioned the potential liability of a landlord to other tenants based on the acts of another tenant. The court noted that a landlord owes a duty to preserve the quiet enjoyment of all tenants, and that in extreme cases, eviction of a troublesome tenant may provide the only practical means to abate a nuisance that affects other tenants. Notably, those other tenants would not share the power of eviction, and would otherwise be limited to remedies of a less certain nature. Here there was evidence that the tenant owned a gun, and that she acted

Page 8 of 9

Legal Research

6/25/12 5:28 PM

strangely by exhibiting spell-casting type behavior, talking to herself, and similar behavior. Several tenants had complained about the actions of the tenant and mentioned their fear of passing in front of her window to go down steps. The court noted that the landlord's failure to evict a nuisance tenant may have been breach of duty to the other tenants, but that the failure of these defendants to eliminate a mere nuisance was not the same as their failing to prevent a serious criminal act. [Davis v. Gomez (1989, 2nd Dist) 207 Cal App 3d 1401, 255 Cal Rptr 743, one tenant was shot and killed by another tenant. Although the landlord was found not liable for the death of the tenant, the court mentioned the potential liability of a landlord to other tenants based on the acts of another tenant. The court noted that a landlord owes a duty to preserve the quiet enjoyment of all tenants, and that in extreme cases, eviction of a troublesome tenant may provide the only practical means to abate a nuisance that tenant owned a gun, and that she acted strangely by exhibiting spell-casting type behavior, talking to herself, and similar behavior. Several tenants had complained about the actions of the tenant and mentioned their fear of passing in front of her window to go down steps. The court noted that the landlord's failure to evict a nuisance tenant may have been a breach of duty to the other tenants, but that the failure of these defendants to eliminate a mere nuisance was not the same as their failing to prevent a serious criminal act. [Davis v. Gomez (1989, 2nd Dist) 207 Cal App 3d 1401, 255 Cal Rptr 743] Trespass dened Page 26-54

Page 9 of 9

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Tenant's Rights in CaliforniaDokument23 SeitenTenant's Rights in CaliforniaStan Burman100% (1)

- The Complete Small Claims Court Guide: Winning Without a LawyerVon EverandThe Complete Small Claims Court Guide: Winning Without a LawyerBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (4)

- Landlord-Tenant & Renters ResourcesDokument2 SeitenLandlord-Tenant & Renters Resourcesarnoldlee1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eviction HandbookDokument113 SeitenEviction HandbookDevinSells67% (6)

- How to Win Your Case in Small Claims Court Without a LawyerVon EverandHow to Win Your Case in Small Claims Court Without a LawyerBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- FAQ's Landlord TenantDokument9 SeitenFAQ's Landlord TenantgrahnegNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constructive EvictionDokument14 SeitenConstructive EvictionBobby Slade100% (1)

- The Pro Se Litigant's Civil Litigation Handbook: How to Represent Yourself in a Civil LawsuitVon EverandThe Pro Se Litigant's Civil Litigation Handbook: How to Represent Yourself in a Civil LawsuitBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Eviction Process and ChartsDokument14 SeitenEviction Process and Chartsstummel6636100% (1)

- Managing Rental Housing: A Complete Reference Guide from the California Apartment AssociationVon EverandManaging Rental Housing: A Complete Reference Guide from the California Apartment AssociationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constructive EvictionDokument1 SeiteConstructive EvictionLarry MicksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Representing Yourself In Court (CAN): How to Win Your Case on Your OwnVon EverandRepresenting Yourself In Court (CAN): How to Win Your Case on Your OwnBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Affirmative Defenses To An Unlawful Detainer (Eviction) Complaint in CaliforniaDokument3 SeitenAffirmative Defenses To An Unlawful Detainer (Eviction) Complaint in CaliforniaStan Burman67% (3)

- Representing Yourself In Court (US): How to Win Your Case on Your OwnVon EverandRepresenting Yourself In Court (US): How to Win Your Case on Your OwnBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Jada Pedron - Landlord Letter OverviewDokument4 SeitenJada Pedron - Landlord Letter Overviewapi-434047870Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rent2rent: Landlords, Agents, Tenants & the Legal Skills You Need to ConsiderVon EverandRent2rent: Landlords, Agents, Tenants & the Legal Skills You Need to ConsiderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Illegal Evictions Can Get You in Trouble For Landlord Harassment - FindLawDokument5 SeitenIllegal Evictions Can Get You in Trouble For Landlord Harassment - FindLawCari Mangalindan MacaalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tenant's RightsDokument120 SeitenTenant's Rightssweetlousblossom0% (1)

- Family Law Attorney Liability Immunities: Malicious Prosecution - Abuse of Process - Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress - Litigation Privilege - Constructive Immunity From Tort Liability for Meritless Litigation and Abusive Litigation Tactics - Divorce - Divorce CourtDokument17 SeitenFamily Law Attorney Liability Immunities: Malicious Prosecution - Abuse of Process - Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress - Litigation Privilege - Constructive Immunity From Tort Liability for Meritless Litigation and Abusive Litigation Tactics - Divorce - Divorce CourtCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eviction ProtectionsDokument4 SeitenEviction ProtectionsTabitha MuellerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Demand Letters: A+ Guides to Writing, #10Von EverandLegal Demand Letters: A+ Guides to Writing, #10Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- How To Succesfully Defend Your California Unlawful Detainer With Motion To Strike FinalDokument86 SeitenHow To Succesfully Defend Your California Unlawful Detainer With Motion To Strike FinalKendra Alexander100% (8)

- Retaliatory Eviction in CaliforniaDokument2 SeitenRetaliatory Eviction in CaliforniaStan Burman86% (7)

- Eviction Defense ManualDokument83 SeitenEviction Defense ManualJulio Cesar Navas71% (7)

- The Law Office of Ryan James SmytheDokument19 SeitenThe Law Office of Ryan James SmytheOrangeCountyBestAttorneys100% (1)

- California Eviction Defense ManualDokument200 SeitenCalifornia Eviction Defense ManualSeasoned_Sol58% (24)

- The California Landlords Eviction Law BookDokument193 SeitenThe California Landlords Eviction Law Bookjr_raffy5895100% (3)

- Tenant Rights ResponsibilitiesDokument27 SeitenTenant Rights ResponsibilitiesstarprideNoch keine Bewertungen

- Los Angeles Municipal Code Rent Stabilization ActDokument89 SeitenLos Angeles Municipal Code Rent Stabilization ActRandell TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tenants Facing EvictionDokument8 SeitenTenants Facing EvictionKimberley Nickole Cleggett100% (1)

- Answer To Unlawful Detainer Complaint in CaliforniaDokument4 SeitenAnswer To Unlawful Detainer Complaint in CaliforniaStan Burman100% (2)

- Landlord HarassmentDokument2 SeitenLandlord HarassmentElena HernadezNoch keine Bewertungen

- TWO IMPORTANT APPEAL DECISIONS FOR CALIFORNIANS IN UD - Ascuncion V Superior Court of San Diego 1980 & THE MEHR DECISIONDokument9 SeitenTWO IMPORTANT APPEAL DECISIONS FOR CALIFORNIANS IN UD - Ascuncion V Superior Court of San Diego 1980 & THE MEHR DECISION83jjmack100% (3)

- Retaliatory Eviction Case Exampleif Annoted in Process Verbal Willimson Eq People Vs v. Superior CourtDokument22 SeitenRetaliatory Eviction Case Exampleif Annoted in Process Verbal Willimson Eq People Vs v. Superior CourtSteven SchoferNoch keine Bewertungen

- California Eviction Defense ManualDokument54 SeitenCalifornia Eviction Defense Manualjacque zidane40% (5)

- Motions in Civil Cases CALIFDokument17 SeitenMotions in Civil Cases CALIFAl C0% (1)

- Tenant Three Day To Pay Rent NoticeDokument3 SeitenTenant Three Day To Pay Rent NoticeOHFinancialNoch keine Bewertungen

- California Unlawful Detainer (Eviction) Document Collection For SaleDokument3 SeitenCalifornia Unlawful Detainer (Eviction) Document Collection For SaleStan Burman100% (1)

- Ud105 - ANSWER-Unlawful DetainerDokument2 SeitenUd105 - ANSWER-Unlawful DetainerSalvadah0% (1)

- Retaliatory Eviction Protection in New York PDFDokument23 SeitenRetaliatory Eviction Protection in New York PDFYatinder Singh100% (1)

- Over 200 Sample Legal Documents For California and Federal LitigationDokument5 SeitenOver 200 Sample Legal Documents For California and Federal LitigationStan Burman100% (1)

- Beat The Landlord in California or How To Delay Your Eviction As Long As PossibleDokument10 SeitenBeat The Landlord in California or How To Delay Your Eviction As Long As PossibleStan Burman100% (1)

- Platinum Sample Document CollectionDokument8 SeitenPlatinum Sample Document CollectionStan BurmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Landlord/Tenant Law: For Public LibrariansDokument53 SeitenLandlord/Tenant Law: For Public LibrariansGary SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Landlord & Tenant NotesDokument25 SeitenLandlord & Tenant NotesMichael Stackhouse100% (2)

- Tenant Resource Guide: 219-19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 Fax: 612-624-7351 E-Mail: Usls@umn - EduDokument13 SeitenTenant Resource Guide: 219-19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 Fax: 612-624-7351 E-Mail: Usls@umn - EduAnonymous lidok7lDiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temp Stay Packet 2020Dokument15 SeitenTemp Stay Packet 2020Christina Ashburn100% (1)

- JDF 78 Motion and Order To Set Aside Default JudgmentDokument2 SeitenJDF 78 Motion and Order To Set Aside Default JudgmentSola Travesa100% (2)

- Landlord Tenantv 1Dokument25 SeitenLandlord Tenantv 1mcm100% (1)

- Closing Dos and DontsDokument24 SeitenClosing Dos and DontsNicki SheltonNoch keine Bewertungen

- UD Day Impending Evictions and Homelessness in Los AngelesDokument37 SeitenUD Day Impending Evictions and Homelessness in Los AngeleslvilchisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To Set Aside Default PDF FormDokument3 SeitenMotion To Set Aside Default PDF Formasandoval1150% (2)

- List of Affirmative Defenses To Unlawful Detainer ActionDokument2 SeitenList of Affirmative Defenses To Unlawful Detainer Actionthecastle21390% (10)

- What To Expect SRL Bench Trial FINAL 0310Dokument22 SeitenWhat To Expect SRL Bench Trial FINAL 0310HeyYoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter From Johnson County Department of HealthDokument1 SeiteLetter From Johnson County Department of HealthJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter of Gratitude To Hurtienne FamilyDokument1 SeiteLetter of Gratitude To Hurtienne FamilyJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Letter To Korrey MahoneDokument4 SeitenFirst Letter To Korrey MahoneJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- McDonald's Resume Cover LetterDokument1 SeiteMcDonald's Resume Cover LetterJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pa's LetterDokument1 SeitePa's LetterJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notice of Claim (Beacon Pointe Apartments, Herman Kittle Properties)Dokument6 SeitenNotice of Claim (Beacon Pointe Apartments, Herman Kittle Properties)James Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notice of Intent To Sue Kroger PharmacyDokument3 SeitenNotice of Intent To Sue Kroger PharmacyJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Third Letter To Timothy Ross Jr.Dokument7 SeitenThe Third Letter To Timothy Ross Jr.James Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Letter To Jose Jorge AndradeDokument3 SeitenSecond Letter To Jose Jorge AndradeJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Letter To Angel JuarezDokument5 SeitenFirst Letter To Angel JuarezJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To Julio MadrigalDokument3 SeitenLetter To Julio MadrigalJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- The First Response of Jose Jorge AndradeDokument2 SeitenThe First Response of Jose Jorge AndradeJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Letter To Timothy RossDokument3 SeitenSecond Letter To Timothy RossJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Letter To Jordan LopezDokument2 SeitenFirst Letter To Jordan LopezJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gmail Updates From Denise MillerDokument5 SeitenGmail Updates From Denise MillerJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Letter To Timothy RossDokument3 SeitenFirst Letter To Timothy RossJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To Jenny Howard (VMC)Dokument2 SeitenLetter To Jenny Howard (VMC)James Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- County Counsel - First Rejection LetterDokument2 SeitenCounty Counsel - First Rejection LetterJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eviction Legal Self-Help Brochure (Rev. 2)Dokument2 SeitenEviction Legal Self-Help Brochure (Rev. 2)James Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Letter To Joshua HuertaDokument1 SeiteFirst Letter To Joshua HuertaJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suzellen Jones (Stanford) - LetterDokument1 SeiteSuzellen Jones (Stanford) - LetterJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gmail - 5-Minute UpdateDokument1 SeiteGmail - 5-Minute UpdateJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stanford Positive Care Clinic LetterDokument1 SeiteStanford Positive Care Clinic LetterJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- District Attorney - Pace Clinic LetterDokument2 SeitenDistrict Attorney - Pace Clinic LetterJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heather Wilson E-Mail CorrespondenceDokument3 SeitenHeather Wilson E-Mail CorrespondenceJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Foundation - Denise Miller - E-Mail Correspondence - 2Dokument6 SeitenLegal Foundation - Denise Miller - E-Mail Correspondence - 2James Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Denise Miller E-Mail CorrespondenceDokument14 SeitenDenise Miller E-Mail CorrespondenceJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medi-Cal Managed Care LetterDokument2 SeitenMedi-Cal Managed Care LetterJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Foundation - Denise Miller - E-Mail CorrespondenceDokument10 SeitenLegal Foundation - Denise Miller - E-Mail CorrespondenceJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Order Granting Peaceful Contact With PACE ClinicDokument2 SeitenOrder Granting Peaceful Contact With PACE ClinicJames Alan BushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feati Bank vs. CADokument4 SeitenFeati Bank vs. CAMulan DisneyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part DDokument13 SeitenPart DJovel LayasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- RD RD: Amen - Compiled NotesDokument12 SeitenRD RD: Amen - Compiled NotesMichelle SulitNoch keine Bewertungen

- COL Corporation and PartnershipDokument9 SeitenCOL Corporation and PartnershipMarianne Hope VillasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mathay vs. Court of AppealsDokument25 SeitenMathay vs. Court of AppealsAaron James PuasoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. de JesusDokument10 SeitenPeople v. de JesusDyords TiglaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stebbins V Wal Mart 04 11 2011Dokument5 SeitenStebbins V Wal Mart 04 11 2011Legal WriterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pennsylvania Opp To Bill of Complaint V.finalDokument43 SeitenPennsylvania Opp To Bill of Complaint V.finalWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Md. Emdadul Hasan Sagar, ID No - 2010235172 PDFDokument7 SeitenMd. Emdadul Hasan Sagar, ID No - 2010235172 PDFNazmul HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central Pangasinan Elec Coop vs. MacaraegDokument11 SeitenCentral Pangasinan Elec Coop vs. MacaraegAira Mae P. LayloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Valpy and Others, Assignees of The Estate and Effects of Edward Brown, A Bankrupt, V Gibson and Another (1847) 136 ER 737Dokument13 SeitenValpy and Others, Assignees of The Estate and Effects of Edward Brown, A Bankrupt, V Gibson and Another (1847) 136 ER 737Jahnavi GopaluniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Law - Unit 1Dokument14 SeitenBusiness Law - Unit 1Zafar IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Succession JY Notes Pre-Finals (Mod 9-11)Dokument84 SeitenSuccession JY Notes Pre-Finals (Mod 9-11)Jandi YangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natalio T. Paril, Jr. For Petitioners. Leovigildo L. Cerilla For Private RespondentsDokument4 SeitenNatalio T. Paril, Jr. For Petitioners. Leovigildo L. Cerilla For Private RespondentsLou StellarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Essential Contract Elements PetDokument22 Seiten1 Essential Contract Elements PetahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sia v. CADokument2 SeitenSia v. CAkkkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Special Proceedings Course Syllabus A.Y. 2020-2021: Also See Arts. 390-392, Family CodeDokument5 SeitenSpecial Proceedings Course Syllabus A.Y. 2020-2021: Also See Arts. 390-392, Family CodeAlexis Von TeNoch keine Bewertungen

- RULES OF COURT EvidenceDokument54 SeitenRULES OF COURT Evidencediona macasaquitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Law I Class 1 CDokument221 SeitenConstitutional Law I Class 1 CCJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bea Hotels NV V Bellway LLC (2007) EWHC 1363 (Comm) (12 June 2007)Dokument13 SeitenBea Hotels NV V Bellway LLC (2007) EWHC 1363 (Comm) (12 June 2007)mameemooskbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gregorio Araneta vs. Philippine SugarDokument2 SeitenGregorio Araneta vs. Philippine SugarDarlene AnneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011 Gutierrez v. House of Representatives20210424 14 W02eh4Dokument88 Seiten2011 Gutierrez v. House of Representatives20210424 14 W02eh4Juan Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bustos v. Court of AppealsDokument8 SeitenBustos v. Court of AppealsGfor FirefoxonlyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Law-CourseraDokument37 SeitenCorporate Law-CourseraLyka Mae Palarca IrangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law Notes - Maxims of EquityDokument28 SeitenLaw Notes - Maxims of EquityNadeem Khan100% (1)

- Case Digest - Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U.S. 714 (1878)Dokument1 SeiteCase Digest - Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U.S. 714 (1878)reiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawsuit Against Sugar Land Urban AirDokument13 SeitenLawsuit Against Sugar Land Urban AirHouston ChronicleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Copypdf Seminar 6 AB1301 Lecture Notes - Vitiating FactorsDokument54 SeitenStudent Copypdf Seminar 6 AB1301 Lecture Notes - Vitiating FactorsJulianne Mari WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Discretion and Judicial ControlDokument17 SeitenAdministrative Discretion and Judicial Controlpintu ramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Restructuring - Merger, Amalgamation, EtcDokument124 SeitenCorporate Restructuring - Merger, Amalgamation, Etcudoshi_1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nolo's Deposition Handbook: The Essential Guide for Anyone Facing or Conducting a DepositionVon EverandNolo's Deposition Handbook: The Essential Guide for Anyone Facing or Conducting a DepositionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Dictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersVon EverandDictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Legal Writing in Plain English: A Text with ExercisesVon EverandLegal Writing in Plain English: A Text with ExercisesBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (2)

- Employment Law: a Quickstudy Digital Law ReferenceVon EverandEmployment Law: a Quickstudy Digital Law ReferenceBewertung: 1 von 5 Sternen1/5 (1)

- Legal Research: a QuickStudy Laminated Law ReferenceVon EverandLegal Research: a QuickStudy Laminated Law ReferenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyVon EverandThe Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Flora and Vegetation of Bali Indonesia: An Illustrated Field GuideVon EverandFlora and Vegetation of Bali Indonesia: An Illustrated Field GuideBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Legal Forms for Starting & Running a Small Business: 65 Essential Agreements, Contracts, Leases & LettersVon EverandLegal Forms for Starting & Running a Small Business: 65 Essential Agreements, Contracts, Leases & LettersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsVon EverandEssential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (2)

- How to Make Patent Drawings: Save Thousands of Dollars and Do It With a Camera and Computer!Von EverandHow to Make Patent Drawings: Save Thousands of Dollars and Do It With a Camera and Computer!Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Admissibility of Expert Witness TestimonyVon EverandAdmissibility of Expert Witness TestimonyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Legal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessVon EverandLegal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (9)

- So You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolVon EverandSo You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesVon EverandLegal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nolo's Essential Guide to Buying Your First HomeVon EverandNolo's Essential Guide to Buying Your First HomeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (43)

- Torts: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideVon EverandTorts: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Nolo's Encyclopedia of Everyday Law: Answers to Your Most Frequently Asked Legal QuestionsVon EverandNolo's Encyclopedia of Everyday Law: Answers to Your Most Frequently Asked Legal QuestionsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (18)

- Everybody's Guide to the Law: All The Legal Information You Need in One Comprehensive VolumeVon EverandEverybody's Guide to the Law: All The Legal Information You Need in One Comprehensive VolumeNoch keine Bewertungen