Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Case Matrix

Hochgeladen von

Aiken Alagban LadinesOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case Matrix

Hochgeladen von

Aiken Alagban LadinesCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CASE HERNANDEZ v.

DBP (1976) Issue: WON action of ptr was properly filed in CFI of Batangas

FACTS Hernandez, an employee of DBP for 21 years retired and was awarded a lot in the private respondent's Housing Project at No. 1 West Avenue, Quezon City, containing an area of 810 square meters with a Type E house. Petitioner sent to the Housing Committee a Cashiers check to cover the cash and full payment of purchase price. However, Chief Accountant & Comptroller of DBP returned to check informing petitioner of the cancellation of the award on the following grounds: (1) that he has already retired; (2) that he has only an option to purchase said house and lot; (3) that there are a big number of employees who have no houses or lots; (4) that he has been given his retirement gratuity; and (5) that the awarding of the aforementioned house and lot to an employee of the private respondent would better subserve the objective of its Housing Project.

ARGUMENTS PTR: filed a complaint in the CFI of Batangas seeking the ANNULMENT OF THE CANCELLATION of the award. He contends that cancellation was illegal for he had already become the owner of H&L. PR: filed MOTION TO DISMISS the complaint on the ground of IMPROPER VENUE contending that since the petitioner's action affects the title to a house and lot situated in QC, the same should have been commenced in the CFI of QC where the real property is located and not in the CFI of Batangas where petitioner resides.

HELD & RATIO It is a well settled rule that venue of actions depends to a great extent on the nature of the action to be filed, whether it is real or personal. A real action is one brought for the specific recovery of land, tenements, or hereditaments. A personal action is one brought for the recovery of personal property, for the enforcement of some contract or recovery of damages for its breach, or for the recovery of damages for the commission of an injury to the person or property. Under Section 2, Rule 4 of the Rules of Court, "actions affecting title to, or for recovery of possession, or for partition, or condemnation of , or foreclosure of mortgage in real property, shall be commenced and tried where the defendant or any of the defendants resides or may be found, or where the plaintiff or any of the plaintiffs resides, at the election of the plaintiff". Petitioners action is not a real but a personal action. As correctly insisted by petitioner, his action is one to declare null and void the cancellation of the lot and house in his favor which does not involve title and ownership over said properties but seeks to compel respondent to recognize that the award is a valid and subsisting one which it cannot arbitrarily and unilaterally cancel and accordingly to accept the proffered payment in full which it had rejected and returned to petitioner. Such an action is a personal action which may be properly brought by petitioner in his residence. We do not agree with the defendants. All the allegations as well as the prayer in the complaint show that this is not a real but a personal action to compel the defendants to execute the corresponding purchase contracts in favor of the plaintiffs and to pay damages. The plaintiffs do not claim ownership of the lots in question: they recognize the title of the defendant J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc. They do not ask that possession be delivered to them, for they allege to be in possession. The case cited by the defendants (Abao, et al. vs. J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc., G.R. No. L-16796, Jan. 30, 1962) is therefore not in point. In that case, as stated by this Court in its decision, the "plaintiffs' action is predicated on the theory that they are 'occupants, landholders,' and 'most' of them 'owners by purchase' of the residential lots in question; that, in consequence of the compromise agreement adverted to above, between the Deudors and defendant corporations, the latter had acknowledged the right and title of the Deudors in and to said lots; and hence, the right and title of the plaintiffs, as successors-in-interest of the Deudors; that, by entering into said agreement, defendant corporations had, also, waived their right to invoke the indefeasibility of the Torrens title in favor of J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc.; and that defendants have no right, therefore, to oust plaintiffs from the lots respectively occupied by them and which they claim to be entitled to hold. Obviously, this action affects, therefore, not only the possession of real property, but, also, the title thereto. Accordingly, it should have been instituted in the Court of First Instance of the Province of Rizal in which said property is situated (Section 3, Rule 5 of the Rules of Court)."

Adamos v. JM Tuason (1968)

The plaintiffs, 33 in all, instituted this action for "Specific Performance and Damages," alleging four (4) causes of action against J.M. Tuason & Co., Inc., and Gregorio Araneta, Inc., the latter in its capacity as managing partner and attorneyin-fact of the former. In the 1st CoA the complaint states that the plaintiffs are in possession of certain residential lots situated in Matalahib and Tatalon, Quezon City, having purchased the same sometime in 1949 from several persons collectively designated as the Deudors; that said lots are all embraced and included in a bigger parcel of land covered by a Torrens title in the name of J.M. Tuason & Co., Inc.; that after 1949 the same lots claimed by herein plaintiffs became the subject-matter of several civil cases in the CFI of Rizal (Quezon City) between the Deudors and J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc.; that on March 16, 1953 the parties in those cases entered into a compromise agreement, subsequently embodied in the decision of the Court, under which the legitimate purchasers of lots from the Deudors, named in a list attached to the said agreement, among them the plaintiffs, "who are to continue and/or who are entitled to elect and have elected to buy their respective lots, from the legal owners who are now the defendants (J.M. Tuason & Co., Inc) shall be credited (the) sums already paid by them under their former purchase contracts from their active predecessors-ininterest;" that it is likewise provided in the compromise agreement that the socalled owners (J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc), now the defendants, shall make new purchase contracts in favor of the plaintiffs with respect to their respective lots acquired by them from the Deudors at the current rate then existing at the time of the execution of the compromise agreement; that the plaintiffs "are ... willing to buy their respective lots and/or elect to continue to purchase the same from the defendants and also to sign new purchase contracts, but the defendants without any legal justification whatsoever, deliberately refused and failed and still refuse

and fail to make new purchase contracts in favor of the herein plaintiffs up to the present time, notwithstanding verbal and written demands made by the plaintiffs to the defendants, and in spite of their written and verbal commitments to plaintiffs." The fourth cause of action contains a claim for damages and attorney's fees. J. M. Tuason & Co., Inc., and Gregorio Araneta, Inc. filed separate motions to dismiss, both pleading improper venue and failure to state a cause of action, and the first alleging, besides, extinctive prescription and misjoinder of parties.

CABUTIHAN v. LANDCENTER (2002) WON venue properly laid was

On December 3, 1996, respondent (Landcenter) entered into a contract with petitioner (Cabutihan). The agreement stipulated that the petitioner would assist the respondent in facilitating and arranging the recovery of certain properties in consideration for 20% of the total area of the property thus recovered. The respondent breached the agreement. Petitioner filed an action for specific performance with damages. Respondent filed a motion to dismiss on the ground that venue was improperly laid. The respondent asserts that since the present case filed by the petitioner is for the recovery of her interest in the respondent corporations land, then the action was in rem, thus according to Rule 4 Section 1, the case should have been filed in the court having jurisdiction over the subject property. The respondent also argued that there was a misjoinder or non-joinder of parties to the case and that the paid filing fee was insufficient.

PTR: action is in personam, not in rem, so venue was properly laid. The fact that she ultimately sought the conveyance of real property not located in the territorial jurisdiction of the RTC of Pasig is, she claims, an anticipated consequence and beyond the cause for which the action was instituted. PR: the present case should have been filed by [petitioner] with the proper court in Paranque, Rizal which has jurisdiction over the Fourth Estate Subdivision because said subdivision is situated in Paranaque, Rizal. Since [petitioner] filed the present case with the court in Pasig City, she chose a wrong venue. RTC ruled in favor of PR

We agree with petitioner. Sections 1 and 2, Rule 4 of the Rules of Court provide an answer to the issue of venue. Actions affecting title to or possession of real property or an interest therein (real actions), shall be commenced and tried in the proper court that has territorial jurisdiction over the area where the real property is situated. On the other hand, all other actions, (personal actions) shall be commenced and tried in the proper courts where the plaintiff or any of the principal plaintiffs resides or where the defendant or any of the principal defendants resides. Commodity Storage case: Where the action affects title to the property, it should be instituted in the trial court where the property is situated. Natl Steel Corp v. CA: Court held that an action in which petitioner seeks the execution of a deed of sale of a parcel of land in his favor x x x has been held to be for the recovery of the real property and not for specific performance since his primary objective is to regain the ownership and possession of the parcel of land. La Tondea Distillers, Inc. v. Ponferrada: private respondents filed an action for specific performance with damages before the RTC of Bacolod City. The defendants allegedly reneged on their contract to sell to them a parcel of land located in Bago City - - a piece of property which the latter sold to petitioner while the case was pending before the said RTC. Private respondent did not claim ownership but, by annotating a notice of lis pendens on the title, recognized defendants ownership thereof. This Court ruled that the venue had properly been laid in the RTC of Bacolod, even if the property was situated in Bago. Siasoco v. CA: The Court reiterated the rule that a case for specific performance with damages is a personal action which may be filed in a court where any of the parties reside. A close scrutiny of National Steel and Ruiz reveals that the prayers for the execution of a Deed of Sale were not in any way connected to a contract, like the Undertaking in this case. Hence, even if there were prayers for the execution of a deed of sale, the actions filed in the said cases were not for specific performance.

In the present case, petitioner seeks payment of her services in accordance with the undertaking the parties signed. Breach of contract gives rise to a cause of action for specific performance or for rescission. If petitioner had filed an action in rem for the conveyance of real property, the dismissal of the case would have been proper on the ground of lack of cause of action. INFANTE v. ARAN Builders Inc. (2007) Aran Builders, Inc. filed before the RTC of Muntinlupa City an action for revival of judgment against Adelaida Infante. o The judgment sought to be revived was based on an action for specific performance and damages which was rendered by the RTC of Makati City. The case at bar involves the enforcement of the private respondents rights over a piece of real property located at Ayala Alabang Subdivision. Because it involves a real action, the complaint should indeed be filed with the RTC of the place where the realty is located (which in this case is Muntinlupa City).

The Makati RTC judgment became final and executory on November 1994 and it decreed that Adelaida Infante was to execute a deed of sale of a lot located at Ayala Alabang Subdivision in favor of Aran Builders, and for Aran Builders to pay the remaining balance of the purchase price;

Section 6 Rule 39 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure: after the lapse of 5 years from entry of judgment and before it is barred by the statute of limitations, a final and executory judgment or order may be enforced by action. The rule does not specify in which court the action of revival of judgment should be filed. o However, in Aldeguer vs. Gemelo: xxx an action upon a judgment may be brought either in the same court where the said judgment was rendered or in the place where the plaintiff or defendant resides, or in any other place designated by the statutes which treat of the venue of actions in general.

Infante filed a motion to dismiss the action for revival of judgment on the grounds that the Muntinlupa RTC has no jurisdiction over the persons of the parties and that the venue was improperly laid. o Muntinlupa RTC: denied Infantes Motion to Dismiss and his subsequent MR. Although the judgment was rendered by the Makati RTC, it must be emphasized that at the time it was rendered, there was still no RTC in Muntinlupa City and hence all cases from Muntinlupa were tried and heard at Makati. With the creation of the RTCs of Muntinlupa City, matters involving properties located in this City and cases involving its residents are now ordered to be litigated before its courts.

General Rules on Venue (Rules of Court): (1) Rule 4 Section 1 (Venue of real actions) actions affecting title to or possession of real property, or interest therein, shall be commenced and tried in the proper court which has jurisdiction over the area wherein the real property involved, or a portion of it, is situated. (2) Rule 4 Section 2 (Venue of personal actions) all other actions may be commenced and tried where the plaintiff or any of the principal plaintiffs resides, or where the defendant or any of the principal defendants resides, or in the case of a nonresident defendant where he may be found, at the election of the plaintiff.

Infante filed an instant special civil action for certiorari before the Court of Appeals. o Infante asserts that the complaint for specific performance and damages before the Makati RTC is a personal action (action in personam) and, therefore, the suit to revive the judgment therein is also personal in nature. Consequently, the venue for the revival of judgment is either in Makati City or Paraaque City where private respondent and petitioner respectively reside. Aran Builders for its part maintain that the subject action for revival of judgment is quasi in rem because it involves and affects vested or adjudged right on a real property; in effect, the venue lies in Muntinlupa City where the property is situated. CA Decision: ruled in favor of Aran Builders. The action for revival of judgment is an action in rem which should be filed with the RTC of the place where the real property is located.

The proper venue depends on the determination of whether the present action for revival of judgment is a real action or a personal action. If it is a real action (i.e., action affects title to or possession of real property or interest therein), then it must be filed with the court of the place where the real property is located. On the other hand, if it is a personal action, then it may be filed with the court of the place where the plaintiff or defendant resides. The previous judgment (1st civil case) has declared respondents right

Infante then filed this present Petition for Review on Certiorari under Rule 45 of the ROC seeking the reversal of the decision of the CA.

to have the title over the disputed property. The respondent has an established interest over the property in question, and to protect such right, respondent instituted the current action to enforce and revive the previous judgment. This action falls under the category of a real action. NOTE: Originally, Muntinlupa City was under the territorial jurisdiction of the Makati courts. However, Section 4 of RA 7154 which amended Section 14 of BP 129 provided for the creation of a branch of the RTC in Muntinlupa. Thus, it is now the RTC in Muntinlupa City which has territorial jurisdiction or authority to validly issue orders and processes concerning real property within Muntinlupa City.

LAM v. ROSILLOSA (1950)

Rosillosa was the owner of a parcel of land planted to coconuts located in Unisan, Quezon Province and acquired through homestead. He sold said parcel of land to Maximo Alpay for 10k. Alpay sold the land to Peregrina for 25k and TCT was issued in her name. Rosillosa instituted civil case in CFI of Quezon Province against Alpay & Peregrina to redeem said property under Public Land Act. (Alpay later on ceased to have interest in property) After defendant failed to appear despite summons, Court ordered Peregrina to execute a deed of resale to Rosillosa upon compensation. Apparently, Peregrina died years before commencement of civil case. Ang Lam, administrator of the estate of Peregrina, filed a petition praying that judgment rendered in civil case be set aside on the ground that the court had not acquired jurisdiction over the person of the deceased. Petition was denied by respondent judge Santiago (CFI Quezon) on the grounds (1) that plaintiff's action was by its nature one in rem; (2) that the petitioner Ang Lam is the surviving husband of the defendant Eugenia Peregrina and had the administration of the land in litigation; and (3) that the decision of the court was handed down on April 2, 1949, whereas the petition to set it aside was presented only on September 26, 1949, that is to say, after the lapse (sc.) of the periods mentioned in section 3 of Rule 38 of the Rules of Court.

SC: Judgment in question is null and void of jurisdiction over the person of the defendant. The attempt of the respondent judge to hold the said summons by publication binding upon the petitioner Ang Lam on the theory that the action was one in rem and that said petitioner is the surviving husband of the defendant and is the administrator of the property in question, is, in our opinion, untenable. An action to redeem, or to recover title to or possession of, real property is not an action in rem or an action against the whole world, like a land registration proceeding or the probate of a will; it is an action in personam, so much so that a judgment therein is binding only upon the parties properly impleaded and duly heard or given an opportunity to be heard. "Actions in personam and actions in rem differ in that the former are directed against specific and seek personal judgments, while the latter are directed against the thing or property or status of a person and seek judgments with respect thereto as against the whole world." (1 C.J.S., 1148.) An action to recover a parcel of land is a real action, but it is an action in personam, for it binds a particular individual only although it concerns the right to a tangible thing. An action for resolution of a contract of sale of real property is an action in personam (Sandejas vs. Robles, 46 Off, Gaz., [Supp. to No. 1], 2031). if, on the other hand, the object is to bar indifferently all who might be minded to make an objection of any sort against the right sought to be established, and if any one in the world has a right to be heard on an allegation of facts which, if true, shows an inconsistent interest, the proceeding is in rem (Grey Alba vs. Cruz, 17 Phil., 49, 62). For instance, an application in rem, for the judgment which may be rendered therein is binding upon the whole world (Reyes vs. Razon, 38 Phil., 480, 482). The probate of a will is a proceeding in rem, because the order of probate is effective against all persons wherever residing. On Jurisdiction The word jurisdiction is used in several different, though related, senses since it may have reference (1) to the authority of the court to entertain a

El Blanco EspanolFilipino v. Palanca (1918)

Engracio Palanca Tanquinyeng y Limquingco mortgaged various parcels of real property in Manila to El Banco Espanol-Filipino. Afterwards, Engracio returned to China and there he died on January 29, 1810 without returning again to the Philippines. The mortgagor then instituted foreclosure proceeding but since

defendant is a non-resident, it was necessary to give notice by publication. The Clerk of Court was also directed to send copy of the summons to the defendants last known address, which is in Amoy, China. It is not shown whether the Clerk complied with this requirement. Nevertheless, after publication in a newspaper of the City of Manila, the cause proceeded and judgment by default was rendered. The decision was likewise published and afterwards sale by public auction was held with the bank as the highest bidder. On August 7, 1908, this sale was confirmed by the court. However, about seven years after the confirmation of this sale, a motion was made by Vicente Palanca, as administrator of the estate of the original defendant, wherein the applicant requested the court to set aside the order of default and the judgment, and to vacate all the proceedings subsequent thereto. The basis of this application was that the order of default and the judgment rendered thereon were void because the court had never acquired jurisdiction over the defendant or over the subject of the action.

particular kind of action or to administer a particular kind of relief, or it may refer to the power of the court over the parties, or (2) over the property which is the subject to the litigation. The sovereign authority which organizes a court determines the nature and extent of its powers in general and thus fixes its competency or jurisdiction with reference to the actions which it may entertain and the relief it may grant. How Jurisdiction is Acquired Jurisdiction over the person is acquired by the voluntary appearance of a party in court and his submission to its authority, or it is acquired by the coercive power of legal process exerted over the person. Jurisdiction over the property which is the subject of the litigation may result either from a seizure of the property under legal process, whereby it is brought into the actual custody of the law, or it may result from the institution of legal proceedings wherein, under special provisions of law, the power of the court over the property is recognized and made effective. In the latter case the property, though at all times within the potential power of the court, may never be taken into actual custody at all. An illustration of the jurisdiction acquired by actual seizure is found in attachment proceedings, where the property is seized at the beginning of the action, or some subsequent stage of its progress, and held to abide the final event of the litigation. An illustration of what we term potential jurisdiction over the res, is found in the proceeding to register the title of land under our system for the registration of land. Here the court, without taking actual physical control over the property assumes, at the instance of some person claiming to be owner, to exercise a jurisdiction in rem over the property and to adjudicate the title in favor of the petitioner against all the world. In the terminology of American law the action to foreclose a mortgage is said to be a proceeding quasi in rem, by which is expressed the idea that while it is not strictly speaking an action in rem yet it partakes of that nature and is substantially such. The expression "action in rem" is, in its narrow application, used only with reference to certain proceedings in courts of admiralty wherein the property alone is treated as responsible for the claim or obligation upon which the proceedings are based. The action quasi rem differs from the true action in rem in the circumstance that in the former an individual is named as defendant, and the purpose of the proceeding is to subject his interest therein to the obligation or lien burdening the property. All proceedings having for their sole object the sale or other disposition of the property of the defendant, whether by attachment, foreclosure, or other form of remedy, are in a general way thus designated. The judgment entered in these proceedings is conclusive only between the parties. It is true that in proceedings of this character, if the defendant for whom publication is made appears, the action becomes as to him a personal action and is conducted as such. This, however, does not affect the

proposition that where the defendant fails to appear the action is quasi in rem; and it should therefore be considered with reference to the principles governing actions in rem.

Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U.S. 714, 24 L. Ed. 565 (1878) Facts Mitchell brought suit against Neff to recover unpaid legal fees. Mitchell published notice of the lawsuit in an Oregon newspaper but did not serve Neff personally. Neff failed to appear and a default judgment was entered against him. To satisfy the judgment Mitchell seized land owned by Neff so that it could be sold at a Sheriffs auction. When the auction was held Mitchell purchased it and later assigned it to Pennoyer. Neff sued Pennoyer in federal district court in Oregon to recover possession of the property, claiming that the original judgment against him was invalid for lack of personal jurisdiction over both him and the land. The court found that the judgment in the lawsuit between Mitchell and Pennoyer was invalid and that Neff still owned the land. Pennoyer lost on appeal and the Supreme Court granted certiorari. Issue Can a state court exercise personal jurisdiction over a non-resident who has not been personally served while within the state and whose property within the state was not attached before the onset of litigation? Holding and Rule (Field) No. A court may enter a judgment against a non-resident only if the party 1) is personally served with process while within the state, or 2) has property within the state, and that property is attached before litigation begins (i.e. quasi in rem jurisdiction). Since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, the validity of judgments may be directly questioned on the ground that proceedings in a court of justice to determine the personal rights and obligations of parties over whom that court has no jurisdiction do not constitute due process of law. Due process demands that legal proceedings be conducted according to those rules and principles which have been established in our systems of jurisprudence for the protection and enforcement of private rights. To give legal proceedings any validity, there must be a tribunal with legal authority to pass judgment, and a defendant must be brought within its jurisdiction by service of process within the state, or by his voluntary appearance. The substituted service of process by publication in actions brought against nonresidents is valid only where property in the state is brought under the control of the court, and subjected to its disposition by process adapted to that purpose, or where the judgment is sought as a means of reaching such property or affecting some interest therein; in other words, where the action is in the nature of a proceeding in rem.

The Oregon court did not have personal jurisdiction over Neff because he was not served in Oregon. The courts judgment would have been valid if Mitchell had attached Neffs land at the beginning of the suit. Mitchell could not have done this because Neff did not own the land at the time Mitchell initiated the suit. The default judgment was declared invalid. Therefore, the sheriff had no power to auction the real estate and title never passed to Mitchell. Neff was the legal owner. Disposition Judgment for Neff affirmed. SHAFFER v. HEITNER FACTS Arnold Heitner (as custodian for Mark Andrew Heitner, owner of one share of stock in Greyhound Corp.) instituted a shareholders derivative suit against Greyhound Corp., Greyhound subsidiary Greyhound Lines, Inc., and 28 members of Greyhounds Board of directors and officers. Heitner brought the suit in the Delaware Court of Chancery of New Castle County, Greyhound's state of incorporation. Heitner simultaneously filed a motion for an order to sequester (i.e. to 'seize' the stock by barring its sale) approximately 82,000 shares of Greyhound stock owned by 21 of the defendants. The defendants were notified by certified mail and by publication in a New Castle County, Delaware newspaper. The defendants responded by entering a special appearance in the Delaware court for the purpose of moving to quash service of process and to vacate the sequestration order and to contest personal jurisdiction, pointing out that none of them had ever set foot in Delaware or conducted any activities in that state. They contended that the ex parte sequestration procedure did not accord them due process of law as required by the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution and that the property seized was not capable of attachment in Delaware. In addition, appellants asserted that they did not have sufficient contacts with Delaware to sustain the jurisdiction of that State's courts. The Delaware state court found that it had quasi in rem jurisdiction, based on a Delaware statute that declared stock owned in a Delaware corporation to be legally located 'in' Delaware. The primary purpose of 'sequestration' is not to secure possession of property pending a trial between resident debtors and creditors on the issue of who has the right to retain it. On the contrary, as here employed, 'sequestration' is a process used to compel the personal appearance of a nonresident defendant to answer and defend a suit brought against him in a court of equity. It is accomplished by the appointment of a sequestrator by this Court to seize and hold property of the nonresident located in this State subject to further Court order. If the

defendant enters a general appearance, the sequestered property is routinely released, unless the plaintiff makes special application to continue its seizure, in which event the plaintiff has the burden of proof and persuasion. ISSUES Can a state obtain personal jurisdiction over a party based on that partys ownership of property in the state? Is quasi in rem jurisdiction subject to the constitutional requirements of minimum contacts? Holding and Rule (Marshall) No. A state cannot obtain personal jurisdiction over a party based merely on that partys ownership of property in the state. Yes. Quasi in rem jurisdiction is subject to the constitutional requirements of minimum contacts. RULES Whether or not a State can assert jurisdiction over a nonresident must be evaluated according to the minimum-contacts standard of International Shoe Co. v. Washington. In rem jurisdiction: due process under the Fourteenth Amendment requires that the basis for jurisdiction must be sufficient to justify exercising jurisdiction over the interests of persons in the thing. The presence of property in a State may allow jurisdiction by providing contacts among the forum State, the defendant, and the litigation; for example, when claims to the property itself are the source of the underlying controversy. Where, as in this case, the property serving as the basis for jurisdiction is completely unrelated to the plaintiffs cause of action, the presence of the property alone, i.e., absent other ties among the defendant, the State, and the litigation, would not support the States jurisdiction. Delawares assertion of jurisdiction over appellants, based solely as it is on the statutory presence of appellants property in Delaware, violates the Due Process Clause, which does not contemplate that a state may make binding a judgment against an individual or corporate defendant with which the state has no contacts, ties, or relations. Appellants holdings in the corporation do not provide contacts with Delaware sufficient to support jurisdiction of that States courts over appellants. Delaware state-court jurisdiction is not supported by that States interest in supervising the management of a Delaware corporation and defining the obligations of its officers and directors, since Delaware bases jurisdiction, not on appellants status as corporate fiduciaries, but on the presence of their property in the State. Though it may be appropriate for Delaware law to govern the obligations of appellants to the corporation and stockholders, this does not mean that appellants have

purposefully availed themselves of the privilege of conducting activities within the forum State. See Hanson v. Denckla. Appellants, who were not required to acquire interests in the corporation in order to hold their positions, did not by acquiring those interests surrender their right to be brought to judgment in the States in which they had minimum contacts. Discussion In Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank and Trust we held certain Fourteenth Amendment rights attach once an adverse judgment in rem directly affects the property owner by divesting him of his rights in the property. If jurisdiction over property involves jurisdiction over a persons interests, the proper standard is the minimum contacts standard of International Shoe. This makes the assertion of jurisdiction over the property an assertion of jurisdiction over the person. Thus, all assertions of jurisdiction must be determined according to the standards of International Shoe and its progeny. Delaware has a strong interest in supervising the management of corporations created within its borders. The legislature must assert that interest, however. Delaware is not a fair forum for this litigation because the officers and directors have never set foot in the state and have not purposefully availed themselves of the benefits and protections of the state. Disposition Reversed. Concurring (Powell) I reserve judgment as to whether ownership of real property in a jurisdiction may provide the contacts necessary for jurisdiction. Quasi in rem jurisdiction should remain valid when real property is involved. Concurring (Stevens) This holding should not be read to invalidate in rem jurisdiction. Concurring in Part and Dissenting in Part (Brennan) The use of minimum contacts is more than justified and it represents a sensible approach to the exercise of state court jurisdiction, however the majoritys approach to minimum contacts is wrong. To be proper, State court jurisdiction must have both notice and a long arm statute. Under this case there is no such statute. As a general rule, a state forum has jurisdiction to adjudicate a shareholder derivative action centering on the conduct and policies of the directors and officers of a corporation incorporated in that State. I therefore would not foreclose Delaware from asserting jurisdiction over appellants were it persuaded to do so on the basis of minimum contacts. Heitner however never pleaded or demonstrated that the defendants had minimum contacts with the state. Greyhounds choice of incorporation in Delaware is a prima facie showing of submission to its jurisdiction. There was a voluntary association with the State of Delaware invoking the benefits and protections of its laws. The majority opinion is purely advisory once it finds that the state statute is invalid.

1. Asiavest v. CA G.R. No. 110263 July 20, 2001 Ponente: DELEON, JR The petitioner Asiavest Merchant Bankers (M) Berhad is a corporation organized under the laws of Malaysia Private respondent Philippine National Construction Corporation is a corporation duly incorporated and existing under Philippine laws. In 1983, petitioner initiated a suit for collection against private respondent before the High Court of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. Petitioner sought to recover the indemnity of the performance bond it had put up in favor of private respondent to guarantee the completion of the Felda Project and the nonpayment of the loan it extended to Asiavest-CDCP Sdn. Bhd. for the completion of Paloh Hanai and Kuantan By Pass; Project. On September 13, 1985, the High Court of Malaya (Commercial Division) rendered judgment in favor of the petitioner and against the private respondent The private respondent was asked to pay 5,108,290.23 Ringgits Following unsuccessful attempts to secure payment from private respondent under the judgment, petitioner initiated on September 5, 1988 the complaint before Regional Trial Court of Pasig, Metro Manila, to enforce the judgment of the High Court of Malaya The RTC of Manila and the CA denied the motion for lack of want of jurisdiction

2.

ISSUE: Whether or not the Malaysian High Court acquired jurisdiction over the PNCC ot the private respondent Contentions of Private Respondent: (more of the rules of procedure) 1. The Malaysian High Court did not serve the summons to the right persons a. The summons was sent to the accountant of the PNCC, Cora Deala; she is not authorized to receive the summons for and in behalf of the private respondent. 2. And that there is no lawyer who will defend or act in behalf of the private respondent a. According to Abelardo, the private respondents executive secretary said that there is no resolution granting or authorizing Allen and Glendhill (the said to be lawyers of the company) to admit all the claims of the petitioner. 3. That the decision of the Malaysian High Court is tainted with fraud and clear mistake of fact/law; since there is no statement of facts and law given which the award is given in favor of the petitioner. Held: Petition Granted. The Malaysian High Court acquired jurisdiction over PNCC due to the following ground: 3.

Due to the fact that the rules of procedure (such as those serving of summons) are governed by the lex fori or the internal law forumwhich is in this case is Malaysia a. it is the procedural law of Malaysia where the judgment was rendered that determines the validity of the service of court process on private respondent as well as other matters raised by it. i. Since the burden of proof of showing that there are irregularities in the serving of summons as to the procedural rules of the Malaysian high court should be shouldered by the private respondents; however, the private respondent failed to show or give proof in the said irregularities therefore the PRESUMPTION of validity and regularity of service of summons and the decision rendered by the High Court of Malaya should stand. On the matter of alleged lack of authority of the law firm of Allen and Gledhill to represent private respondent, not only did the private respondent's witnesses admit that the said law firm of Allen and Gledhill were its counsels in its transactions in Malaysia. a. but of greater significance is the fact that petitioner offered in evidence relevant Malaysian jurisprudence to the effect that i. it is not necessary under Malaysian law for counsel appearing before the Malaysian High Court to submit a special power of attorney authorizing him to represent a client before said court, ii. that counsel appearing before the Malaysian High Court has full authority to compromise the suit iii. that counsel appearing before the Malaysian High Court need not comply with certain pre-requisites as required under Philippine law to appear and compromise judgments on behalf of their clients before said court. On the ground that collusion, fraud and, clear mistake of fact and law tainted the judgment of the High Court of Malaya, no clear evidence of the same was adduced or shown. Since the burden of proof again should be shouldered by the private respondent a. As aforestated, the lex fori or the internal law of the forum governs matters of remedy and procedure. i. Considering that under the procedural rules of the High Court of Malaya, a valid judgment may be rendered even without stating in the judgment every fact and law upon which the judgment is based, then the same must be accorded respect and the courts in the jurisdiction cannot invalidate the judgment of the foreign court simply because our rules provide otherwise.

Belen v. Chavez Facts: The petition originated from the action for the enforcement of a foreign judgment against petitioners, spouses Belen, filed by private respondent spouses

Pacleb before the RTC of Rosario, Batangas. The complaint alleged that respondents secured a judgment by default rendered by a certain Judge John W. Green of the Superior Court of the State of California, which ordered petitioners to pay private respondents the amount of $56,204.69, representing loan repayment and share in the profits plus interest and costs of suit. The answer by the petitioners claimed that petitioners liability had been extinguished via a release of abstract judgment issued in the same collection case since the petitioners were really residents of the USA. On 5 August 2003, the RTC rendered a Decision in favor of the plaintiffs. On 24 November 2003, private respondents sought the execution of the RTC decision to levy real properties belonging to defendants. Petitioners filed a Rule 65 petition before the Court of Appeals, imputing, among others, the RTC grave abuse of discretion tantamount to lack or excess of jurisdiction (1) in rendering its decision although it had not yet acquired jurisdiction over their persons in view of the improper service of summons; and (2) in considering the decision final and executory although a copy thereof had not been properly served upon petitioners; Issues: (1) Whether or not the RTC acquired jurisdiction over the persons of petitioners through either the proper service of summons or the appearance of the late Atty. Alcantara on behalf of petitioners; and (2) Whether or not there was a valid service of the copy of the RTC decision on petitioners. Ruling: (1) YES, the RTC acquired jurisdiction over the persons of the defendants through appearance of Atty. Alcantara on behalf of petitioners. In an action strictly in personam, personal service on the defendant is the preferred mode of service, that is, by handing a copy of the summons to the defendant in person. If the defendant, for justifiable reasons, cannot be served with the summons within a reasonable period, then substituted service can be resorted to. While substituted service of summons is permitted, it is extraordinary in character and in derogation of the usual method of service. Records of the case reveal that herein petitioners have been permanent residents of California, U.S.A. since the filing of the action up to the present. From the time Atty. Alcantara filed an answer purportedly at the instance of petitioners relatives, it has been consistently maintained that petitioners were not physically present in the Philippines. That being the case, the service of summons on petitioners purported address in San Gregorio, Alaminos, Laguna was defective and did not serve to vest in court jurisdiction over their persons. Nevertheless, the Court of Appeals correctly concluded that the appearance of Atty. Alcantara and his filing of numerous pleadings were sufficient to vest jurisdiction over the persons of petitioners. Through certain acts, Atty. Alcantara was impliedly authorized by petitioners to appear on their behalf. For instance, in support of the motion to dismiss the complaint, Atty. Alcantara attached thereto a duly authenticated copy of the

judgment of dismissal and a photocopy of the identification page of petitioner Domingo Belens U.S. passport. These documents could have been supplied only by petitioners, indicating that they have consented to the appearance of Atty. Alcantara on their behalf. In sum, petitioners voluntarily submitted themselves through Atty. Alcantara to the jurisdiction of the RTC. (2) NO, there was no valid service of the copy of the decision to the petitioners. As a general rule, when a party is represented by counsel of record, service of orders and notices must be made upon said attorney and notice to the client and to any other lawyer, not the counsel of record, is not notice in law. The exception to this rule is when service upon the party himself has been ordered by the court. In cases where service was made on the counsel of record at his given address, notice sent to petitioner itself is not even necessary. Undoubtedly, upon the death of Atty. Alcantara, the lawyer-client relationship between him and petitioners has ceased, thus, the service of the RTC decision on him is ineffective and did not bind petitioners. Since the filing of the complaint, petitioners could not be physically found in the country because they had already become permanent residents of California, U.S.A.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- SPA SampleDokument2 SeitenSPA SampleAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Affidavit of Discrepancy SampleDokument1 SeiteJoint Affidavit of Discrepancy SampleAiken Alagban Ladines100% (5)

- Judicial Affidavit - SampleDokument7 SeitenJudicial Affidavit - SampleAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

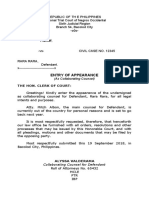

- Entry of Appearance: (As Collaborating Counsel)Dokument2 SeitenEntry of Appearance: (As Collaborating Counsel)Aiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revised Rules On Administrative Cases in The Civil ServiceDokument43 SeitenRevised Rules On Administrative Cases in The Civil ServiceMerlie Moga100% (29)

- Joint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsDokument1 SeiteJoint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases - SourcesDokument15 SeitenCases - SourcesAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waiver of Rights - SampleDokument1 SeiteWaiver of Rights - SampleAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christmas CardsDokument1 SeiteChristmas CardsAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ST Kiss The Miss Goodbye 8x10 1Dokument1 SeiteST Kiss The Miss Goodbye 8x10 1Aiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of LossDokument1 SeiteAffidavit of LossAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Materials UsedDokument3 SeitenMaterials UsedAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ClubsDokument1 SeiteClubsAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colds/Flu Prevention Through VaccinationDokument1 SeiteColds/Flu Prevention Through VaccinationAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstract of Tomato PlantationDokument1 SeiteAbstract of Tomato PlantationAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effective Communication As A Means To Global PeacDokument2 SeitenEffective Communication As A Means To Global PeacAiken Alagban Ladines100% (1)

- LTFRB Revised Rules of Practice and ProcedureDokument25 SeitenLTFRB Revised Rules of Practice and ProcedureSJ San Juan100% (2)

- Affidavit of LossDokument1 SeiteAffidavit of LossAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- VaccinationDokument1 SeiteVaccinationAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Celebrating His Love - EditedDokument1 SeiteCelebrating His Love - EditedAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compassion in Action - EditedDokument1 SeiteCompassion in Action - EditedAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar SchedDokument1 SeiteBar SchedAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Galatians 5 Living by The Spirit's PowerDokument1 SeiteGalatians 5 Living by The Spirit's PowerAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daily RemindersDokument4 SeitenDaily RemindersAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Registered VotersDokument1 SeiteRegistered VotersAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answer - Reswri 2Dokument6 SeitenAnswer - Reswri 2Aiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- PassportDokument2 SeitenPassportAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax NotesDokument6 SeitenTax NotesAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resolution To Open Bank AccountsDokument1 SeiteResolution To Open Bank AccountsAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code of Professional ResponsibilityDokument3 SeitenCode of Professional ResponsibilityAiken Alagban LadinesNoch keine Bewertungen