Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Cum Sa Inveti

Hochgeladen von

med_carmenOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cum Sa Inveti

Hochgeladen von

med_carmenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PART ONE SCIENTIFIC PRINCIPLES CHAPTER 1 READING EFFECTIVELY TO ATTAIN PROFICIENCY IN SURGERY RICHARD H. BELL, Jr., LINNEA S.

HAUGE, AND DEBRA A. DaROSA KEY POINTS During a residency in surgery, the successful surgeon-to-be advances from a novice, who must follow rules to achieve good outcomes, to becoming proficient, which means that accumulated knowledge and experience allows him/her to respond correctly to situations in a more automatic and effortless manner. Real learning (more than just memorization for the short term) occurs when information becomes stored in long term memory. Learning with understanding occurs when the student or resident has accumulated sufficient knowledge in long-term memory that he/she recognizes familiar patterns in the new situations that are encountered. Reading is a critical tool for acquiring surgical knowledge. Reading that leads to deep understanding can be facilitated by conscious strategies before, during, and after reading that increase the likelihood that information will be retained in long-term memory and be accessible when needed. The student of surgery can and should develop conscious strategies for assessing the extent to which their reading results in deep comprehension of the educational material. LEARNING, MEMORY, AND PROGRESSION TO EXPERTISE If you are reading this book, the chances are high that you will be (or are or have been) a surgery resident on the first day of your first rotation of your first year. Imagine (or remember) the call to the emergency room to evaluate a new patient with a complex problem, perhaps a 70-year-old male with an upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and known coronary artery disease. By that point in your education as a doctor, you will have learned enough basic rules about resuscitation to take a few stepscheck the airway, start an intravenous line, send off blood for a type and cross match, perhaps place a Foley catheter. Soon, however, your knowledge, skills, and abilities are overwhelmed by the complexity of the situation. Perhaps the patients blood pressure falls, or the electrocardiogram pattern changes. Chances are that you turn at that point to a senior or chief resident, who comes to your aid, seemingly cool in the face of chaos, and makes precise and rapid adjustments in the patients treatment, develops a rapid differential diagnosis, and orders the appropriate diagnostic testing. Finally, the attending surgeon arrives with an air of confidence born of experience, seems to recognize the problems immediately, and, after an incisive set of questions, makes a decision to take the patient to the operating room. What has happened to allow the senior resident or senior surgeon to achieve that level of competence and confidence? The beginning of a surgical residency marks the start of a new way of learning. Prior to that time, you may well have invested effort in accumulating knowledge of facts or understanding of concepts that you knew you were extremely unlikely to ever need beyond the next examination. Suddenly, however, as a resident you are placed in a situation where you need to rapidly acquire information that you can use to build a sophisticated understanding of diseases and operations. You have a huge amount to learn and dont have much time to waste on nonproductive educational activities. Much more than ever before, you need to retain the information you have encountered, store that information in ways that allow you to retrieve it in the future, and relate the information to other pieces of information you have acquired.

How can we describe the transition from the first-year resident with a limited repertoire to the respected senior surgeon? A model that is widely used is the Dreyfus model,1 originally used to describe the performance progression of U.S. Air Force pilots. The Dreyfus system (Fig. 1.1) specifies five levels of accomplishment: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. A novice is capable of following rules, but not capable of changing the rules to adapt to new circumstances or knowing when the rules dont apply. For example, the novice is capable of generating a standard set of postoperative orders, but would not be able to significantly modify them for individual patients. When the novice sees a patient, he or she has had so little experience that he or she cannot call on mental images of a diseasethe novice is forced to depend on analytic reasoning to try to tie the pathophysiology he or she has studied to symptoms and signs. The advanced beginner still functions largely on the basis of rules, but begins to develop some flexibility in applying them. The advanced beginner has had enough clinical experience to begin to recognize patterns in the patients he or she has encountered. The competent surgeon begins to identify patterns in situations and has started to develop mental models of diseases and operations that guide his or her decision making. To a limited extent, the competent surgeon is able to apply knowledge of the known to new and unknown situations. At this stage, experience begins to supplant rules. The competent surgeon also begins to accept responsibility for the care of the patient and becomes more emotionally involved with patients. The proficient surgeon is able to effortlessly recognize many situations, drawing on his or her extensive real-world experience and significant prior learning stored in memory. The proficient surgeon may appear to operate from instinct because of the fluidity of his or her decision making, but the instinct is derived from a store of experience that has created models that allow the surgeon to choose quickly among competing scenarios. FIGURE 1.1. The Dreyfus model of performance (see also Carraccio C, Benson B, et al. From the educational bench to the clinical bedside: translating the Dreyfus developmental model to the learning of clinical skills. Acad Med 2008;83:761767). Finally, the expert seems to always get it right. The expert routinely comes up with an optimal performance and appears to do it effortlessly. The experts mental models of disease are so strong that he or she recognizes atypical features of cases that others miss. The expert may depend so much on second nature that he or she actually has difficulty describing his or her decision-making process. In general, the development of expertise in a given area takes 10 years or more. Most experts in surgery have focused on a particular area of surgery for decades. The Science of Learning and Memory The activities of your brain are conducted by cells, of which there are approximately 1 trillion. The number of brain cells does not increase during life; rather, the development of the brain results from increasing complex connections made between the brains neurons, of which there are about 100 billion, the remainder of the brain cells being glial cells that organize and support the neurons. Neurons communicate with each other via dendrites and axons, the dendrites carrying impulses to the neuron and the axon carrying impulses from the neuron to the dendrites of surrounding neurons. Because an individual neuron can have thousands of dendrites, the number of possible interactions between cells becomes almost unlimited. Learning occurs when the brain acquires new information; memory is the process through which that information is retained and stored for later retrieval.2 When learning occurs, certain neurons start to

function together. Repeated activation of those neurons makes subsequent activations faster and in some cases automatic, leading to the creation of memory. Storage of learning in memory in turn activates additional neuronal connections and associations. Memory appears to be of three types: immediate memory, working memory, and long-term memory. Immediate memory allows you to recall enough information to quickly perform a task such as entering a patients name into a computer and spelling it correctly. Working memory confers the ability to process information during the completion of tasks that take minutes to hours. Long-term memory refers to the storage of information for months or years. Storage of this type of information starts with the information being encoded by the hippocampus, which then exports it to long-term storage areas. A very important goal in surgical education is to increase the likelihood that important information will be retained and stored in long-term memory. Two factors that have been shown to be important in ensuring retention are sense and relevance. Sense implies that the information fits in with the learners previous experience. Relevance means that the information is much more likely to be retained if it has meaning for the learner and is related to the learners real-life activities. Both of these principles are very important to keep in mind in the training of surgeons. As a resident, trying to read about endocrine surgery may not be very effective in promoting long-term memory if you are in the midst of a demanding vascular surgery rotation and have not had previous exposure to very many patients with endocrine problems. Learning with Understanding Learning with understanding occurs when the learner can make sense of new information in light of previous experience and can also see that the information is relevant to his or her learning needs. As one learns with understanding, pieces of information begin to relate to each other and eventually information is clustered in mental models or scripts. Material that is learned with understanding can not only be recalled but can also be used when novel but related situations are encountered. Recent work suggests that it is the elaborateness and depth of these illness scripts that characterize the expert physician.3 Learning with understanding is not easy. As noted previously, learning with understanding can be quite difficult if the learner is not sufficiently familiar with a subject to be well positioned to learn more. Sometimes the prior information that a learner possesses about a subject is incorrect and is difficult to eradicate. In surgery, learning with understanding is complicated when the learner is presented with conflicting information or misinformation from faculty or reading materials. The remainder of this chapter deals with reading and how one can use a textbook in a way that is most likely to lead to learning with understanding and timely progress toward proficiency or expertise. Surgeons learn in many ways, and some are undoubtedly inclined to rely more on doing than reading. Reading is critical to learning to become a surgeon because it is a major way that experts transmit their accumulated understanding to those who are at lower stages in their comprehension. It is very hard to think of another way of learning that does this more efficiently. Having said this, reading is often not done well, not done efficiently, and not done at the right time and place. In the ensuing pages, we hope to offer practical advice about using this textbook and other printed materials to your maximal advantage in your surgical career. READING FOR RETENTION AND TRANSFERREMEMBERING FOLLOWS UNDERSTANDING How do you read a chapter and more easily remember the material? What study strategies enable you to read efficiently, yet also permit you to retrieve the information from memory for use in patient care and on examinations? Why is it that sometimes you are asked a question on a topic about which you

remember reading, but your recollection of the details is clouded? These are common concerns expressed by surgeons working to build and maintain a solid knowledge base in an era when the amount of knowledge is doubling every 18 months.4 In this portion of the chapter, we will explain approaches individuals may take to learn new information and then describe reading and study activities that promote deep understanding and help translate new information into retrievable knowledge. TABLE 1.1 STRATEGIES TO ACHIEVE DEEP STRUCTURED READING Surface Versus Deep Structured Learning Approaches The retention of information in long-term memory is affected by a students approach to learning. Individuals have tendencies to use either a surface or deep structured approach to reading and studying, although any given individual may change his or her approach at times. Readers who take a surface approach read on autopilot, not processing or fully thinking about the information being read. These individuals may go through the motions of highlighting sections in the text, but they dont carefully choose key points. These learners tend to memorize facts indiscriminately, treat what is being read as unrelated bits of information, and find difficulty in later explaining what they read in their own words.5 Surface readers glean satisfaction from the number of pages covered, but then have difficulty remembering the content because the words were never translated into personally meaningful information. Surface-level readers search for facts that might appear on the test but not for the meaning of the text. A surface approach leads to temporary and superficial engagement with the educational material and does not promote long-term retention or understanding because little active thinking occurred during reading. A negative association has been reported between the surface study approach and exam performance. This approach is common in learners who are stressed, have performance anxiety, have little interest in the topic, possess limited time management skills and try to read too much in too little time, or lack the ability to discriminate between essential and less important concepts, thereby missing the forest for the trees and drowning in information overload.6 In contradistinction, deep structured learners are motivated by natural curiosity and a genuine need to know. Their purpose for reading is to acquire information that is considered relevant and personally meaningful. They take control of their own learning and seek to fully understand a topic. They recognize when they understand what is being read, and also recognize when they need more or different information to fully comprehend the material. These learners mentally engage with the information they read by questioning the material, asking themselves about key points, analyzing the material for relationships with what they already know through experience or prior knowledge, and identifying underlying principles to guide their thinking. A deep structured learning approach is an active, integrative process. It results in learners translating the words, charts, and other forms of information into an organized mental picture. This deep and structured approach leads to long-term retention.7 Study Considerations and Strategies Some readers fall asleep while reading, or find themselves having to reread a paragraph several times. Others commit to studying for a block of time, only to start hours later because they found other things to do. Active reading requires a persons full attention. Even with the best of intentions, a readers success can be compromised if concentration is lacking. It is important to minimize or eliminate visual or auditory distractions and to improve the study environment if there is poor lighting, clutter, or uncomfortable seating. Internal distractors (hunger, performance anxiety, sleepiness, etc.) require attention as well. In order to use study time well, keen and consistent concentration are needed.8,9 Table 1.1 demonstrates a three-step reading approach designed to promote deep structured learning.10 In the first stage, learners prepare before reading by activating their prior knowledge and setting

themselves up to read with a purpose. The second stage suggests ways to process the information while reading and make it personally meaningful. The last step reinforces the need to revisit and rehearse what was read to better transfer the information from short-term to long-term memory. Before Reading: Activate Prior Knowledge There is a well-established correlation between prior knowledge and reading comprehension.11,12 Before reading new material, the learner should carefully reflect on what he or she already knows about the topic and how it relates to other subjects already studied. Prior knowledge is the foundation upon which new information is built. A person with a high level of prior knowledge on a given topic can comprehend what is being read in less time and with less effort than a person who has limited experience or knowledge about the subject. Prior knowledge helps learners construct concepts and make meaning out of what is being read.13,14 By activating existing knowledge about a topic before reading more about it, the learner can identify knowledge gaps and then actively read with the clear aim to fill them. Several strategies exist for activating ones prior knowledge, including reflection and recording, interactive discussions, question and answer development, hypotheses development, and deciding what information about the subject matters the most. Reflection and Recording. One of the simplest methods is to bring to mind the subject and note what you know about it. You can revisit existing knowledge by listing the chapter headings and subtitles and documenting what you already know. For example, assume that a chapter entitled Shock lists eight subtitles: pathophysiology, evaluation of shock, classification of hemorrhage, treatment of hemorrhagic shock, resuscitative fluids, special situations, experimental resuscitative fluids, and complications of shock. The process of briefly recording what you already know about each of these areas stimulates memory, clarifies what is known, and highlights learning gaps or needs. This prepares you to read actively and selectively to fill knowledge voids while also efficiently verifying that your comprehension in areas where you have prior knowledge is sufficient. Interactive Discussion with Others. Some people activate prior knowledge best through verbal exchange with others. Talking with a colleague about a specific topic can help highlight key points to be studied, highlight lessons learned through personal experiences, and clarify ones understanding about the topic. These discussions can also yield important questions about the topic that require attention as well as provide an organizational structure for thinking about the subject. Question Development. Generating questions about a topic prior to reading helps you articulate what you think is important to know. It encourages you to think broadly about the subject and anticipate what information might be needed to take care of a patient with the given disease. You might anticipate a question posed by faculty or on an exam, or connect the topic with a patient care problem youve heard about, personally encountered, or anticipate being faced with in the future. When authoring questions on a topic, you should include questions related to word definitions, causeeffect relationships, and comparisoncontrast information (how do the symptoms of appendicitis differ from other diseases causing abdominal pain?). The process of asking questions about a topic (I wonder why.; what causes?; how is X similar to Y?; how is it different than Z?; what if the patient is?) requires you to think deeply about what you dont understand about the topic so reading can be focused to address identified learning needs. Noting questions before reading and then recording the answers while reading activates preknowledge, links the new information to forethought, and helps translate what is read to real-life situations, which makes the information all the more memorable. Prediction or Hypothesis Development. Learners benefit from making predictions about various aspects of a topic by tapping into what they already know and predicting how it relates to the subject under

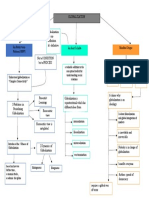

study. For example, if reading about rectal cancer, the reader might predict that multimodality therapy is frequently employed, based on his or her preexisting knowledge of pelvic anatomy and lymphatic drainage and past experience with other gastrointestinal malignancies. By hypothesizing answers to key knowledge gaps, readers can test their assumptions through focused reading. Deciding What Matters Most. Because time for study is limited, it is helpful to pause before reading about a topic to think about which aspects of it are critical, important, or useful to know. Focusing your reading can be done by any of the methods previously mentioned, as well as by simply listing personal learning objectives such as, By the end of this study period concentrating on benign breast disease, I want to be able to do the following: (a); (b). This process activates prior knowledge by determining what components of the topic are most important to you so you can then actively read the chapter with your objectives guiding your study. During Reading: Taking Notes If you dont possess a photographic memory or an experts large store of prior knowledge on a subject so that material being read can be easily organized into long-term memory, note taking is needed or the material will be easily forgotten. It is inefficient to re-read each chapter or even review highlighted paragraphs. Interactive note taking leads to stronger memories and improved concentration while reading. According to Pauk and Owens,15 note taking focuses attention on what is being read, which strengthens the original memory trace of the material. In addition, it results in a document available for later review and reinforcement. The aim is to create condensed notes driven by the identified learning needs from the Before Reading exercises described earlier, formatted for efficient future review and self-testing. Three note-taking methods are described in this section: visual notes, verbal notes, and combined visual/verbal notes. Visual Notes. Visual notes help learners organize information because they show relationships and hierarchies of concepts. Types of graphic organizers include tables, pictures, flowcharts, mind maps, and diagrams.16 Graphic organizers are often already published in the text and serve to highlight the importance of the information. Reading the published version, however, is less useful than constructing your own because creating your own version requires more information processing. Nevertheless, it can be useful to copy graphic organizers from a book to carry in a lab coat pocket to review during windows of available time or access when a clinical opportunity arises. Another strategy is to omit the data in parts of the published graph and later fill in the blanks to further reinforce understanding and retention. Tables are useful for comparing and contrasting common types of details across variables. For example, a table would be helpful to learn about the various imaging techniques for pancreatic cancer. The column headings might include Name of Test, Cost, Risks, Sensitivity, Specificity, and Positive Predictive Value. This approach allows you to extract information from the books narrative and place it in the correct location in the table format. The finished table enables you to compare and contrast the tests and create a big picture view of the multiple factors involved in choosing an optimal diagnostic tool. A flowchart is a picture of the separate steps of a process in sequential order. Translating the material you read into a flowchart helps you think through ifthen scenarios and can uncover your incorrect or unclear decision pathways. After reading a segment of a chapter on a particular disease entity, you can, for example, draw a scheme for working up a jaundiced patient or create an algorithm for the treatment of pulmonary embolus.

Mind maps, sometimes referred to as concept maps, relate facts or ideas to other facts or ideas. Relationships and patterns across information are easily seen in mind maps. A mind map is a structured graphic display of an individuals conceptual scheme within a well-circumscribed domain.17,18 There are various approaches to developing mind maps, but most methods share similar steps. The first step, the brainstorming stage, occurs by drawing or writing the topic in the center of the page (Fig. 1.2). If the chapter under study is about gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the reader would write the word GERD in the middle of a large sheet of blank paper. Lines are then drawn from the center topic outwardly to represent the main ideas or categories that are written or illustrated in the reading. Subheadings from the book could be used for these spokes, or the reader can choose his or her own collection of key ideas. For example, one spoke might have printed on it Diagnosis and a second spoke may contain the word Treatment. A third spoke might be Epidemiology, and a fourth might read Complications. Given that our minds dont think in a linear fashion, mind or concept maps enable readers to build branches and subbranches onto the main spokes or build more main spokes, depending on what they are thinking at the time. Any number of branches can be added to the major spoke lines. Learners continue to build their maps as their thoughts and search and find mental association powers are unleashed. Mapping allows for free-flow thinking and spontaneous thought and decreases the chances of premature closure about a topic or subtopic, which typically happens when using an outline approach. FIGURE 1.2. A basic mind map dealing with the topic of gastroesophageal reflux.

Once the initial brainstorming map is completed, the organizational stage needs to occur. In this phase, readers redo their mind maps, sequencing the branches in sort of meaningful order. During this phase, readers may see hierarchies or new associations that can serve as a basis for organizing or modifying the maps branches or subbranches. Additional details on how to construct mind maps are published elsewhere.19 Other types of graphic organizers include diagrams or pictures. The latter can be helpful, for example, in summarizing a segment of a chapter that describes anatomy. Anatomic pictures can either be drawn or copied from the Internet or other printed source and used to note structures. Creating graphics helps readers activate background knowledge, strengthens metacognitive skills, strengthens their ability to construct meaning from the printed word, and reinforces understanding. Verbal Notes. Research suggests that underlining (or highlighting) while reading leads to greater understanding than reading alone, but writing notes while reading is significantly better for retention than underlining. Creating summaries in your own words of the material you read is critical to converting learning into memory. If notes cant be done easily, then the information is not well enough understood to be incorporated for the long term. One note-making system worth considering is the Cornell method.15 This method, pictured in Figure 1.3, provides a format for condensing and organizing notes. It makes use of paper with a 2.5-inch margin on the left and a 6-inch area on the right in which to write notes. While reading, you write cue words in the left margin and key phrases or points in the right. Later, when reviewing notes, you can view the cue word while simultaneously covering up the key phrases to discern whether you can extemporaneously come up with the key points. For example, while studying the principles of tumor biology, cue words in the left margin might read how cancers develop, role of the host, clinical staging, etc. The bottom 2 inches of the page are used to write summary information or to note areas that need additional study. Templates for the Cornell method note formats and instructions about how to use them can be found on the Internet.

Combined Methods. There are many ways you can interact with the material you read, be it verbally or visually. With todays technology, you could set up a Web page for your reading notes. The Web page could include visual and verbal notes, all organized using a structure that makes sense to you. After Reading: Rehearse The importance of reviewing and rehearsing notes cannot be overemphasized in terms of its importance to long-term memory. Rehearsing material repeatedly helps it become overlearned and thus embedded in your memory. The passage of time can be detrimental to memory, but returning to review notes at the start of each study session can significantly increase retention. There is consistent evidence that the process of rehearsal and recitation transfers information from short-term memory into long-term memory.20 Recitation or rehearsal can include reflecting on the topic, writing about it, answering the questions you posed at the prereading stage, and/or talking to yourself or others about it. It is best to write or talk aloud when rehearsing because it involves multiple senses, which increases the chances of remembering the material. Consider reviewing by offering to teach the topic to othersto teach is to learn twice. When reviewing information, you will be more successful if your notes are organized in a manner that supports a systematic search, such as by hierarchies or categories. The rehearsal process requires processing the information by analyzing it, not merely reciting it. FIGURE 1.3. The Cornell method for note taking (see also Pauk W, Owens R. How to Study in College, 8th ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company Publishers; 2005).

Self-assessment is a helpful form of rehearsal. Multiple-choice practice exams are convenient, but openended questions allow for a richer interaction with the material and avoid some of the artifact in multiple-choice questions that is introduced by distractors. In summary, rehearsal is a critical part of learning. Periodic and consistent review will help you refresh and build your memory. MONITORING YOUR LEVEL OF READING COMPREHENSION Early in your education, your teachers helped you develop strategies to assess and improve reading comprehension. These strategies, known as comprehension monitoring, are likely so engrained in your reading process that now you give little thought to them. Comprehension strategies are specific, learned procedures that foster active, competent, self-regulated, and intentional reading.21 The number and type of comprehension monitoring strategies that you use is predictive of retention.22 Therefore, it is recommended that you do a personal inventory of your strategies before embarking on the difficult task of reading a surgery textbook to ensure that you are using your reading time as effectively as possible (Table 1.2). Your goals for text comprehension should be related to your desired outcome. If you are reading to learn and remember the factual answers to questions you anticipate will be asked of you during an upcoming conference, your strategies may be confined to recitation or listing. If your goal is to understand how or why a patient responds to a particular drug, your need for deeper processing requires that you use more elaborate comprehension monitoring strategies such as schematic mapping or written summaries. Studying for a high-stakes examination, such as the American Board of Surgery Qualifying or Certifying Examination, requires more elaborate comprehension strategies aimed at deeper processing. TABLE 1.2 SUMMARY OF POSSIBLE STRATEGIES FOR MAXIMIZING READING COMPREHENSION

Comprehension monitoring is a metacognitive activity that includes self-evaluation and self-regulation. Self-evaluation refers to whether or not you understand what you have read. Self-regulation is the act of taking steps to correct problems you detect during self-evaluation. Of importance in this process is a sincere attempt to judge future performancein other words, do I understand this well enough now to do well on a future test? Or make a diagnosis in a patient? The judgments you make about future performance impact what and how much you study, so honest and accurate self-assessment is important. Being familiar with ones own limitations about knowledge, memory, and performance under stress is critical for enhancing accurate judgments about future comprehension performance. Accurate predictions require perspective, a capacity for self-criticism, and an understanding and acceptance of biases that lead to cognitive error.23,24 Cognitive dispositions to respond (CDRs) to situations in predictable ways can lead to errors in critical thinking. An example of a CDR that can lead to cognitive error is search satisfying, which occurs when a search is called off once something suitable is found. In diagnosing a source of pain, for example, a plausible explanation is encountered, causing you to cease the search for others. Awareness of these pitfalls and using a strategy for reducing cognitive error (continuing your search for other potential causes of pain) are known as cognitive forcing strategies. Getting perspective and reflecting on ones thinking process during reading, or in clinical situations, is an effective means for avoiding or minimizing potential errors in critical thinking.23 The judgments you make about reading comprehension are limited by the subjectivity inherent to selfevaluation.25 The more familiar you are with a topic, the more likely you will overestimate your comprehension of it.26 While we recommend that you read about topics related to your current rotation and patient encounters in order to take advantage of the retention effect of activating prior knowledge, be aware that when you are reading about a topic of immediate familiarity, you may overestimate your understanding of the material. Using a range of evaluation strategies to monitor your comprehension can help to avoid misinterpreting familiarity as understanding. The more coherent or easier textual material is to process, the higher you will judge your comprehension to be.26 Reading texts and review guides that provide abbreviated overviews of surgical topics may be an expeditious way to cover a topic. However, the easier-to-process text may give you the misimpression that you comprehend more than you actually do about the subject you are reading. Massed re-reading, or reading text twice in a row, has been shown to improve memory of information in the text on free recall and also improve the accuracy of comprehension monitoring.27 However, recent studies of massed re-reading compared to single reading demonstrate that massed re-reading is not an effective means of improving performance on multiple-choice tests.28 Re-reading may be valuable when content is not familiar. However, the fluency gained during a re-read can be misunderstood as improved comprehension when, in fact, massed re-reading alone does not typically result in the deeper processing necessary for the level of comprehension that leads to retention. Comprehension accuracy can be improved by reducing uncertainty about the context in which you will need to recall information.26 Familiarizing yourself with the examination format and with the type of information that will be targeted in the test can improve your judgment about your readiness. Another recommendation for improving accuracy of judgments about comprehension involves using colleagues to anchor your judgments. Reducing the subjectivity inherent in self-evaluation can be accomplished by talking with others about the text after reading it. Using your performance results from previous exams can serve as an effective guide for reading goals. A review book that mirrors the complexity of the questions you will face on an exam can also help

reduce the uncertainty you may have about your future comprehension performance. Using a good review guide or question bank in conjunction with your textbook reading can both help you become familiar with test format and assess your retention. While taking practice tests, stop at intervals to review your answers (e.g., every 10 questions) and consider your justification for the responses you gave. This type of self-assessment has been shown to improve future test performance, a result attributed to the critical thinking or reasoning required by the process.29 Rephrasing and justification about reasoning are also metacognitive strategies that can improve retention and future comprehension performance.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Literature and Skepticism (Pablo Oyarzun)Dokument232 SeitenLiterature and Skepticism (Pablo Oyarzun)Fernando MouraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Modes of SpeciationDokument3 SeitenModes of SpeciationRichard Balicat Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Lesson Plan 1 ElaDokument12 SeitenLesson Plan 1 Elaapi-242017773Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Fanmade Translation Dramatis Personae II (By Blues and Aophis)Dokument50 SeitenFanmade Translation Dramatis Personae II (By Blues and Aophis)BulshockNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Criminalistic SDokument2 SeitenCriminalistic SEdmund HerceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- GCWORLD Concept MapDokument1 SeiteGCWORLD Concept MapMoses Gabriel ValledorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Mystery of NegationDokument5 SeitenMystery of NegationAbe Li HamzahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Bias-Free LanguageDokument26 SeitenBias-Free LanguageFerdinand A. Ramos100% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- How Google WorksDokument9 SeitenHow Google WorksHoangDuongNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Documented Essay About EmojisDokument8 SeitenDocumented Essay About EmojisSweet MulanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daily Lesson Log Subject English Grade Level: 8 Grading Period: I. ObjectivesDokument2 SeitenDaily Lesson Log Subject English Grade Level: 8 Grading Period: I. ObjectivesArchelSayagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Toyota Forklift 02 5fg28!02!5fg30 Parts CatalogDokument22 SeitenToyota Forklift 02 5fg28!02!5fg30 Parts Catalognathanielsmith070288xgd100% (115)

- Ilhaam (Enlightenment) A Play by Manav Kaul: Scene - IDokument19 SeitenIlhaam (Enlightenment) A Play by Manav Kaul: Scene - IPrateek DwivediNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Traditional Public Administration Versus The New Public Management: Accountability Versus Efficiency James P. PfiffnerDokument10 SeitenTraditional Public Administration Versus The New Public Management: Accountability Versus Efficiency James P. PfiffnerChantal FoleriNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- ProspectingDokument21 SeitenProspectingCosmina Andreea ManeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Where You Stand Determines What You SeeDokument6 SeitenWhere You Stand Determines What You SeeMylene Rochelle Manguiob Cruz100% (1)

- Trolldómr in Early Medieval Scandinavia-Catharina Raudvere PDFDokument50 SeitenTrolldómr in Early Medieval Scandinavia-Catharina Raudvere PDFludaisi100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- A Study of The Semiotics of Print AdvertisementsDokument42 SeitenA Study of The Semiotics of Print AdvertisementsMay100% (1)

- Conflict ManagementDokument12 SeitenConflict ManagementRaquel O. MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CYP Case Study Assignment Virginia Toole 20260933 Dec 3, 2019 Part 2Dokument9 SeitenCYP Case Study Assignment Virginia Toole 20260933 Dec 3, 2019 Part 2Ginny Viccy C TNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Muhammad The Last Prophet in The Bible by Kais Al-KalbyDokument293 SeitenMuhammad The Last Prophet in The Bible by Kais Al-KalbyWaqarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Ethical Decision Making and Ethical LeadershipDokument11 SeitenEthical Decision Making and Ethical LeadershipmisonotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voelz - Newton and Einstein at The Foot of The CrossDokument14 SeitenVoelz - Newton and Einstein at The Foot of The CrossEric W. RodgersNoch keine Bewertungen

- BRMM 575 Chapter 2Dokument5 SeitenBRMM 575 Chapter 2Moni TafechNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anticipating Strategy DecayDokument14 SeitenAnticipating Strategy DecayRoshela KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idiomatic Expressions Module 1Dokument20 SeitenIdiomatic Expressions Module 1Jing ReginaldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- College of St. John - Roxas: ACTIVITY SHEETS (WEEK 2-Methods of Philosophizing)Dokument3 SeitenCollege of St. John - Roxas: ACTIVITY SHEETS (WEEK 2-Methods of Philosophizing)Lalaine LuzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Adventist Movement Its Relationship To The Seventh Day Church of God PDFDokument54 SeitenThe Adventist Movement Its Relationship To The Seventh Day Church of God PDFCraig MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 20 RobocupDokument17 SeitenLecture 20 RobocupKartika MunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- BROSUR 58th TEFLIN Conference 2g38ungDokument3 SeitenBROSUR 58th TEFLIN Conference 2g38ungAngela IndrianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)