Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Usfg Framework

Hochgeladen von

Ellen DymitOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Usfg Framework

Hochgeladen von

Ellen DymitCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

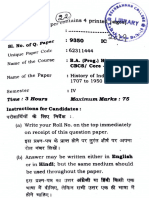

MDAW 2011File Name

Lab Name

1NC-Framework

A. InterpretationThe Affirmative Needs to Defend the Enactment of the Plan by the United States Federal Government B.Violation: they dont use the United States federal government as their actor B. Vote Negative 1. Its Bad For EducationThe Affirmative Kills Our Ability to Debate the Policy Aspects of the Debate Which is what We Prepared for in the First Place, Means We Lose All the Educational Aspects of Competition and Fairness 2. Policy Debates About Space Policy are Crucial to Educate the PublicInformed and Viable Democracy is Only Possible Under Our Framework

Brooks 7 (Jeff, Writer and Political Activist, The Space Review, http://www.thespacereview.com/article/898/1)JFS

I

think we should solve our problemshere on Earth before we go into space.Thisline, or some facsimile of it, has probably been heard countless timesby just about every advocate of space exploration. For many people, it seems to sum up the totality of their thinking on the subject. Not a few politicians invokeiton those rare occasions when space exploration comes up in political discourse. In October of 2006, on the 49th anniversary of the launch of Sputnik, CBS News anchor Katie Couric summarized this attitude when she concluded

her nightly broadcast by saying, NASAs requested budget for 2007 is nearly $17 billion. There are some who argue that money would be better spent on solid ground, for medical research, social programs or in finding solutions to poverty, hunger and homelessness I cant help but wonder what all that money could do for people right here on planet Earth. When space advocates hear this argument, it is difficult not to become irritated or even a little angry. When something that one cares about a great deal is treated with such disparagement, getting upset is a natural reaction. However, responding with irritationand anger does not help and, if anything, merely strengthens the other person inhis or her belief that space exploration is notsomething that should be a national priority. Its important for space advocates to understand that this opinion is held by people not because they are hostile to space exploration, but because they lack sufficient information about it . Thanks to the media, whichgenerally covers space-related stories only when something goeshorribly wrong, a general

impression has been created that space exploration does nothing more than produce a rather small amount of scientific information, of no practical use to anybody, at enormous cost to the taxpayer. Once people have settled into a comfortable belief about something, getting them to change their opinion is far froman easytask.

2. Framework is an A-Priori Voting IssueThe Lack of Effective common Basis for Communication Makes Debate Impossible, Turns Back Fairness and Education

Shively, 2k(Assistant Prof Political Science at Texas A&M, Ruth Lessl, Partisan Politics and Political Theory, p. 181-2)JFS

The requirements given thus far are primarily negative. Theambiguistsmust say "no" to-they must reject and limit-some ideas and actions. In what follows, wewill also find that they must say "yes" to some things. In particular, they must say "yes" to the idea of rational persuasion. This means, first, that they must recognizethe role of agreement in political contest, or the basic accord that is necessary to discord. The mistake that the ambiguists make here is a common one. The mistake isin thinking that agreement marks the end of contest-thatconsensus kills debate. But this is true only if the agreement is perfect-if there is nothing at all left to question or contest.In most cases, however, our agreements are highly imperfect.We agree on some matters but not on others, ongeneralities but not on specifics, on principles but not on their applications, and so on. And thiskind of limited agreement is the starting condition ofcontest and debate. As John Courtney Murray writes:We hold certain truths; therefore we can argue about them.It seems to have been one of the corruptions of intelligence by positivism to assume that argument ends when agreement is reached. In a basic sense, the reverse is true. There can be no argument except on the premise, and within a context, of agreement. (Murray 1960, 10) In other words, we cannot argue about something

if we are not communicating: if we cannot agree on the topic and terms of argument or if we have utterly different ideas about what counts as evidenceor good argument. At the very least, we must agree about what it is that is being debated before we can debate it. For instance, one cannot have an argument about euthanasia with someone who thinks euthanasia is a

musical group. One cannot successfully stage a sit-in if one's target audience simply thinks everyone is resting or if those doing the sitting have no complaints. Nor can one demonstrate resistance to a policy if no one knows that it is a policy. In other words, contest is meaningless if there is a lack of agreement or communication about what is being contested. Resisters, demonstrators, and debaters must havesome shared ideas about the subjectand/or the terms of their disagreements. The participants and the target of a sit-in must share an understanding of the complaint at hand. And a demonstrator's audience must know what is being resisted. In short, the contesting of an idea presumes some agreement about what that idea is and how one might go about intelligibly contesting it. In other words, contestation rests on some basic agreement or harmony.

Page 1 of 2

MDAW 2011File Name

Lab Name

Framework

3. Our Framework is a Prerequisite to All Your Impact ArgumentsOnly Roleplaying as Policymakers About Space Can Allow For True Political Engagement and the Advancement of Social Goals

Stilgoe 6 (Jack, research fellow in science and tech @ U of London, Demos,

http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/exploration/Public/DEMOS_Space_Jury_final_report_v5.pdf)JFS Citizens as policymakersI always thought that those in control say right, I know what I want to do and where we want to go. On the first day of the jury, Colin Hicks, director-general of the British National Space Centre, talked about his role. Asked by jurors who set his agenda, he replied that it was set by the UK Space Board. "And what," he was asked, "is the link between them and us?" His answer was as honest as it was telling. He said his democratic legitimacy is derived from the Space Board, which is chaired by Lord Sainsbury. Lord Sainsbury is a government minister, who is appointed by the current government. The current government is voted in by UK citizens. And that is the link. Unsurprisingly, the jury felt that regular public involvementin ESA strategy is the only way to real involvement and public support for a space exploration programme . Clear communication ofESAs activities and decisions is not enough the jurors wanted to shapeESAs planning, not just hear about itafter the event. Jurors saw this as having real mutual benefit. The ideas and fresh, external perspectives of the public could be of real value."A new pair of eyes is always useful. "Scientists are working in the lab all day, mostly talking to other scientists. Public involvement will keep them grounded, help them work out what's important for everyone, and how to spend the money, our money, better." So the public could play a more active role in helping to maximise the value of space exploration for their fellow tax payers. But there was debate over the extent to which the public should be directly involved in the decisions of space exploration strategy and policy? What questions might this address? Where we should be exploring (should we be going to Mars), or how we should be going about the exploration (robotic or manned missions)? Who should we be working with, how much should we be spending, and ultimately, why are we carrying out space exploration in the first place? There was a large degree of 'pragmatic humility' that emerged about the scope of public inputs. Far from expecting input into every decision madeat ESA, or undermining the importance of scientific expertise, participants were very wary about expressing opinions on scientific priorities.They had strong ideas about where they feel their opinion is backed up and valid (in evaluating the cost, image and communication of missions, and their educational potential for example) and where it is more shaky. Generally, jurors were agreed on the idea that only an informed public would provide useful input, and an uninformed public could not be expected to. In their opinion, the responsibility here lay with ESA. Following a long discussion on this issue, one jury member summed up the groups thinking: "First of all you've got to educate people about it [space exploration], then you've got to do the marketing, andonly then, at the end of it, when you then listen, you're going to get valuable feedback. If you polledthe whole of the UK right now, I'm fairly certain that they would say, 'I don't agree with much about space' or at the least say, 'I don't care'." In short, to have an opinion ona space explorationpolicy, youalso need to have an interest in and understanding of explorationitself. This could be built at both macro and micro levels. The mass methods of communication suggested in the previous section are important as well as genuine and representative dialogue at the micro level. The latter approach might take the form of further citizens' juries in other ESA member states, or by inviting interested but non-expert citizens onto committees as representatives of the wider public.

Page 2 of 2

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Corey Robin The Politics and Antipolitics of Fear 1Dokument30 SeitenCorey Robin The Politics and Antipolitics of Fear 1Ellen DymitNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPS NegDokument41 SeitenSPS NegEllen DymitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lady Gaga Promotes A Capitalist SystemDokument2 SeitenLady Gaga Promotes A Capitalist SystemEllen DymitNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 NCDokument4 Seiten1 NCEllen DymitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Draft Environmental Impact Report Volume 1 For The Alon Bakersfield Refinery Crude Flexibility ProjectDokument660 SeitenDraft Environmental Impact Report Volume 1 For The Alon Bakersfield Refinery Crude Flexibility ProjectenviroswNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loads 30 Jun 21Dokument954 SeitenLoads 30 Jun 21Hamza AsifNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13 Feb 2021 Daily DoseDokument13 Seiten13 Feb 2021 Daily DoseShehzad khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- B.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019Dokument22 SeitenB.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019lakshyadeep2232004Noch keine Bewertungen

- PIL NotesDokument19 SeitenPIL NotesGoldie-goldAyomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subhadra Kumari Chauhan - BiographyDokument3 SeitenSubhadra Kumari Chauhan - Biographyamarsingh1001Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thomas Aquinas and the Quest for the EucharistDokument17 SeitenThomas Aquinas and the Quest for the EucharistGilbert KirouacNoch keine Bewertungen

- PMBR Flash Cards - Constitutional Law - 2007 PDFDokument106 SeitenPMBR Flash Cards - Constitutional Law - 2007 PDFjackojidemasiado100% (1)

- SIA, Allan Ignacio III L. 12044261 Gelitph - Y26: Short Critical Essay #2Dokument1 SeiteSIA, Allan Ignacio III L. 12044261 Gelitph - Y26: Short Critical Essay #2Ark TresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningDokument7 SeitenUsing L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningIsabellaSabhrinaNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statcon - Week2 Readings 2Dokument142 SeitenStatcon - Week2 Readings 2Kê MilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cebu Provincial Candidates for Governor, Vice-Governor and Sangguniang Panlalawigan MembersDokument76 SeitenCebu Provincial Candidates for Governor, Vice-Governor and Sangguniang Panlalawigan MembersGinner Havel Sanaani Cañeda100% (1)

- Registration Form For Admission To Pre KGDokument3 SeitenRegistration Form For Admission To Pre KGM AdnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Field Study-1 Learning Episode:1 4 Activity 14: The Teacher As A Person and As A ProfessionalDokument5 SeitenField Study-1 Learning Episode:1 4 Activity 14: The Teacher As A Person and As A ProfessionalIlex Avena Masilang100% (3)

- SGLGB Form 1 Barangay ProfileDokument3 SeitenSGLGB Form 1 Barangay ProfileDhariust Jacob Adriano CoronelNoch keine Bewertungen

- LANGUAGE, AGE, GENDER AND ETHNICITYDokument16 SeitenLANGUAGE, AGE, GENDER AND ETHNICITYBI2-0620 Nur Nabilah Husna binti Mohd AsriNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESTABLISHING A NATION: THE RISE OF THE NATION-STATEDokument10 SeitenESTABLISHING A NATION: THE RISE OF THE NATION-STATEclaire yowsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1: The Rizal Law, Literature and The Philippine SocietyDokument4 SeitenChapter 1: The Rizal Law, Literature and The Philippine SocietyRomulus GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tamanna Garg Roll No - 19-14 6 Sem 3rd Year Assignment of Modern Political PhilosophyDokument17 SeitenTamanna Garg Roll No - 19-14 6 Sem 3rd Year Assignment of Modern Political PhilosophytamannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broward Sheriffs Office Voting Trespass AgreementDokument20 SeitenBroward Sheriffs Office Voting Trespass AgreementMichelle SolomonNoch keine Bewertungen

- West Philippine SeaDokument14 SeitenWest Philippine Seaviva_33100% (2)

- Styhre, Alexander - Precarious Professional Work - Entrepreneurialism, Risk and Economic Compensation in The Knowledge Economy (2017, Springer International Publishing)Dokument263 SeitenStyhre, Alexander - Precarious Professional Work - Entrepreneurialism, Risk and Economic Compensation in The Knowledge Economy (2017, Springer International Publishing)miguelip01100% (1)

- History of Australian Federal PoliceDokument36 SeitenHistory of Australian Federal PoliceGoku Missile CrisisNoch keine Bewertungen

- RP VS EnoDokument2 SeitenRP VS EnorbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ph102 Thesis StatementsDokument2 SeitenPh102 Thesis StatementsNicole Antonette Del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migrant Voices SpeechDokument2 SeitenMigrant Voices SpeechAmanda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Free Ancient Asiatics PDFDokument175 SeitenFree Ancient Asiatics PDFOsiadan Khnum Ptah100% (1)

- 10 Barnachea vs. CADokument2 Seiten10 Barnachea vs. CAElieNoch keine Bewertungen

- COA Decision on Excessive PEI Payments by Iloilo Provincial GovernmentDokument5 SeitenCOA Decision on Excessive PEI Payments by Iloilo Provincial Governmentmaximo s. isidro iiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines laws on referendum and initiativeDokument17 SeitenPhilippines laws on referendum and initiativeGeorge Carmona100% (1)