Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Social Justice Through Affirmative Action: MBA-IV CSR& HV and Ethics (Unit-4)

Hochgeladen von

Parihar BabitaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Social Justice Through Affirmative Action: MBA-IV CSR& HV and Ethics (Unit-4)

Hochgeladen von

Parihar BabitaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Social Justice through Affirmative

Action

MBA- IV CSR& HV and Ethics

( Unit-4)

Affirmative Action

It is a positive action taken to redress the

imbalances that are the result of previous

discriminatory practices.

INDIAS AFFIRMATIVEACTION PROGRAMME

Indias affirmative action (AA) programme is primarily caste-

based, although there is some AA for women in the electoral

sphere. AA in India, as elsewhere in the world, is contentious

for three reasons.

First, there is considerable debate over the assessment of

caste disparities, the prima facie reason for the existence of

AA whether these are significant at all; if yes, to what extent

and in which sphere; and whether they have been narrowing

over time.

Second, there is a larger debate about whether caste is the

valid indicator of backward-ness or should AA be defined in

terms of class/income or other social markers, such as

religion.

Third, there is the overarching debate about whether AA is

desirable at all, in any form, regardless of which social identity

is used as its anchor.

In the polarised debate around AA, it is either

demonised as the root of all evil or valorised as the

panacea for eliminating discrimination. It is worth

noting at the outset that Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the chief

architect of the constitution of independent India, who

ensured that AA was constitutionally mandated,

himself did not see AA as a panacea.

He did not believe that the caste system could be made

less malignant. He said my ideal would be a society

based on Liberty, Equality and Fraternity [the caste

system] means a state of slavery a society in which

some men are forced to accept from others the

purposes which control their conduct (em-phasis in the

original).

He was constantly engaged with the question of

strategies and instruments which would lead to the

annihilation of caste altogether

However, while the debates around AA are emotionally

charged, it is important to take stock of AA dis-passionately

through an evidence-based approach.

Available national data on caste are defined by the needs of

the affirmative action program which divides the population

into initially three, and now four, broad groups: Scheduled

Castes (ex-untouchable jatis, SC), on average about 18

percent of the Indian population; Scheduled Tribes (ST), on

average about 8 percent of the Indian population; Other

Backward Classes (OBCs, a heterogeneous collection of Hindu

low castes, some non-Hindu communities and some tribes

which are not included in the STs), not yet counted by the

census; however according to the 66th round of the National

Sample Survey (2009-10), these constitute 43 percent of the

rural and 39 percent of the urban population and Others

(the residual; everyone else)

.

Given that data do not allow us

to isolate the upper castes,

Social discrimination

It needs to be emphasized at the outset that

calculations based on this categorization will

underestimate the disparity between the two

ends of the jati spectrum. While the term

Scheduled Castes is a product of this official

terminology, several members of the ex-

untouchable jatis prefer to self-identify

themselves as Dalit the originally Sanskrit

but now Marathi term, meaning oppressed

or broken, which is used as a term of pride.

The idea of preferential treatment for caste and

tribal groups perceived to be the lowest in social

and eco-nomic hierarchy predates Indian

independence. The constitution of newly

independent India continued the idea of

preferential policies, declared untouchability illegal

and espoused the ideal of a casteless society. This

section discusses the (contemporary) rationale for

affirmative action towards designated castes and

tribes. In other words, given that this policy

originated in the early twentieth century, the

arguments in favour of AA are not restated as they

originated, but are being reiterated with

contemporary evidence.

There is sufficient evidence that amply

demonstrates the various aspects of

stigmatization, exclusion and re-jection that

Dalits continue to face in contemporary India

.

In rural India, despite the breakdown of the

traditional subsistence economy, caste

continues to exert its strong presence in many

different dimensions.

Economic discrimination

Average wages for SCs and Others differ across all

occupation categories, and there are a number of

decom-position exercises which divide the average

wage gap into explained and discriminatory

components

The fact that the two groups enter the labour market

with sub-stantial differences in education levels

indicates pre-market discrimination. There is plenty of

evidence which documents the substantial gaps

between SCs and Others in access to education, quality

of education, access to resources that could enhance

learning, and also of active discrimination inside

schools by teachers

Such pre-market discrimination insures that outcomes

will necessarily be unequal, even if there were no

active labour market discrimination

The evidence on persistence of caste-based economic

discrimination in rural areas is perhaps not as

surprising as the evidence from urban areas, especially

in the modern, formal sector jobs. In rural areas

individuals are more easily identified by their caste

status and presumably are more inclined to pursue

caste based occupa-tions given the correspondingly

lower spread of the modern, formal economy

In view of the unambiguous evidence on

discrimination, AA becomes essential to

guarantee representation to Dalits in preferred

positions. It should be noted, however, that AA in

India, due to the specific forms it takes, is not a

complete remedy for discrimination, if not for any

other reason than the fact that AA is applicable

only to the public sector, whereas the evidence of

discrimination is overwhelmingly from the private

sector, which is becoming increasingly important

in the Indian economy.

Compensation for historical wrongs

Finally, social policy ought to compensate for

the historical wrongs of a system that

generated systematic dis-parity between caste

groups and actively kept untouchables at the

very bottom of the social and economic order.

This argument has been used forcefully in

certain international context (for instance, in

Australia for the stolen generation and in

South Africa for the injustice to Blacks during

Apartheid).

However, given the complex and long history of the

Indian sub-continent, the use of this argument in

the context of caste-based oppression and

untouchability has to proceed with extreme

caution, as several right-wing outfits would like to

extend this argument to other arenas by invoking

completely unsubstantiated, often manufactured

injustices against the so-called indigenous

inhabitants, and ask for compensation for historical

wrongs. For a region marked by large waves of

migration over centuries, it is not clear who the

original inhab-itants of the region are. Thus, the

definition of historical wrongs is a site marked by

bitter contestation, and therefore, the question of

compensation is a fraught one.

Coming to the gross violations against

particular castes resulting from centuries of

untouchability, the argument of compensation

for historical wrongs could be, and has been

used as one of the elements in the case for

AA. However, the case for AA as a compensa-

tion for contemporary exclusion is just as

strong, even if one did not view it as necessary

to remedy historical exclusion.

IMPLEMENTATION OF QUOTAS

Overall, the implementation of SC-ST quotas

has improved in all spheres, but despite

safeguards, it remains uneven. Given that

there is no formal systematic monitoring of

the implementation of quotas, they remain

subject to the vagaries of political will and an

overall lackadaisical attitude.

Implementation of quotas in higher

education

Access to education by caste can be, and has

been, analysed at various levels literacy rates,

quality of educa-tion, primary- to- middle school

transition and evidence of discrimination inside

schools. From the strict point of view of

implementation of AA, however, we need to

focus on a few key statistics, while recognising

that the problem of equitable access and

representation across caste groups in the sphere

of education is far too large and complex to be

captured through these few numbers.

Political reservations

The one arena in which quotas have been

implemented completely is the sphere of political

reservations. In principle, SC and ST candidates

are free to contest other, non-reserved seats.

However, since first general elections in 1952, SC-

ST elected representatives have virtually no

presence in these two elected bodies outside of

the reserved seats. This suggests that if

reservations had not been in existence, the

probability that these groups would have the

representation they currently have would be very

low.

ASSESSMENT OF THE AFFIRMATIVE

ACTION PROGRAM

Matters of merit

The most common criticism of the AA measures

is that they go against the consideration of merit

and effi-ciency by allowing candidates access to

preferred positions in higher education and

public sector jobs that they would otherwise not

have access. The latter part of this statement is

obvious--quotas are meant precisely for that.

Productivity impact of affirmative action

In the first empirical study of the effects of AA in the labor market,

Deshpande and Weisskopf 2011 focused on the Indian Railways to

assess if AA, i.e. the presence of SC-ST employees who have gained

entry through quotas, has impacted productivity negatively.

Analyzing an extensive data set on the operations of one of the

largest employers in the public sector in India, the study found no

evidence whatsoever to support the claim of critics of affirmative

action that increasing the proportion of SC and ST employees will

adversely impact productivity or productivity growth. On the

contrary, some of the results suggest that the proportion of SC and

ST employees in the upper (A and B) job categories is positively

associated with productivity and produc-tivity growth.

Assessing affirmative action in higher education

All available evidence indicates that a large majority of

SC-ST candidates owe their presence in institutions of

higher education to reservation policies. While

empirical studies on effects of AA in higher education

are very few due to lack of data, the few studies that

exist point towards the fact that SC-ST students find it

hard to succeed in competitive entrance examinations

due to past handicaps (lack of good quality schooling,

lack of access to special tutorial or coaching centres

that prepare candidates for open competitive

examinations and so forth).

Impact of political reservations

Pande (2003) examines if reservation in state

legislatures for disadvantaged groups increases their

political influence. She finds that political reservations

increase transfers (such as welfare expenditure in the

state plan) towards groups that are targeted by

reservations. Thus, reservation for SCs and STs does

provide them with policy influence. Similar conclusions

at the village level are seen in a study by Besley, Pande

et al (2004), which finds that the availability of public

goods for SC-ST households increases significantly if

the constitu-ency is reserved, compared to non-

reserved constituencies.

The important thing to note is that the

existing AA program and these supplementary

measures need not be considered mutually

exclusive. They can strengthen and reinforce

each other. Admittedly, all these measures

have costs, but the benefits of integrating

large sections of nearly 160 million Dalits and

unleashing the sup-pressed reservoir of talent

is the need of the hour for the rapidly growing

Indian economy.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Sierra Leone Private Investment and Financial Sector Development: Trends and StatisticsVon EverandSierra Leone Private Investment and Financial Sector Development: Trends and StatisticsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Concepts, Theories and Issues in DevelopmentDokument16 SeitenConcepts, Theories and Issues in DevelopmentEman NolascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. An Opportunity for Climate Action in Latin America and the CaribbeanVon EverandForest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. An Opportunity for Climate Action in Latin America and the CaribbeanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignemnt and Case For OBDokument6 SeitenAssignemnt and Case For OBgebgenzNoch keine Bewertungen

- The International Telecommunications Regime: Domestic Preferences And Regime ChangeVon EverandThe International Telecommunications Regime: Domestic Preferences And Regime ChangeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kishan Environment ProjectDokument13 SeitenKishan Environment Projectkishan singh pariharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploring Artificial Intelligence Applications in Human Resource Management 1532 5806 23-5-221Dokument12 SeitenExploring Artificial Intelligence Applications in Human Resource Management 1532 5806 23-5-221ponnasaikumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sons of Soil DoctrineDokument6 SeitenSons of Soil Doctrineanonymous 212Noch keine Bewertungen

- LL & LW ProjectDokument21 SeitenLL & LW ProjectadvikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISDCS Outline - 2015Dokument5 SeitenISDCS Outline - 2015nikaro1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- Torts FinalDokument17 SeitenTorts FinalKaran MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of sustainable tourismDokument11 SeitenPrinciples of sustainable tourismSumit Ghosh100% (1)

- Aim Approach To HRMDokument11 SeitenAim Approach To HRMKAVYA SHANU K100% (1)

- Traditional Knowledge and Intellectual PropertyDokument4 SeitenTraditional Knowledge and Intellectual PropertyPrincess Hazel GriñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rawls' Two Principles of Justice and the MarketDokument4 SeitenRawls' Two Principles of Justice and the MarketRodilyn BasayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Project On JurisprudenceDokument23 SeitenJamia Millia Islamia: Project On JurisprudenceSushant NainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Traditional Knowledge and Human RightsDokument12 SeitenTraditional Knowledge and Human RightsParth BhutaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of JusticeDokument27 SeitenTheories of JusticeARSH KAULNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report On Animal RightsDokument8 SeitenReport On Animal RightsYashashvi Rastogi100% (1)

- Term Paper About Ethics in Research by Ahmad KhaseebDokument6 SeitenTerm Paper About Ethics in Research by Ahmad KhaseebAhmad0% (1)

- The Role of Engineers in Economic DevelopmentDokument8 SeitenThe Role of Engineers in Economic DevelopmentlogzieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Globalisation On Indian SocietyDokument10 SeitenImpact of Globalisation On Indian Societysalmanabu25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Law Project FinalDokument37 SeitenEnvironmental Law Project FinalSamreenKhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justice As The First Virtue of A SocietyDokument39 SeitenJustice As The First Virtue of A SocietyHimanshu GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NTCC Project Report Cover Page and List of ContentsDokument4 SeitenNTCC Project Report Cover Page and List of ContentsAhmad DanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affirmative Action in EducationDokument48 SeitenAffirmative Action in EducationSushman DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- DSNLU Project on Economic and Legal Issues of Agri Market AccessDokument20 SeitenDSNLU Project on Economic and Legal Issues of Agri Market AccessKamlakar ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 21: A Reservoir of Right To Water?: Praveen Patil Shahaji Law College, Kolhapur, MaharashtraDokument9 SeitenArticle 21: A Reservoir of Right To Water?: Praveen Patil Shahaji Law College, Kolhapur, Maharashtratanmaya_purohitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violence in Cartoons: The Effect of Media On Children: Alswaeer. MDokument29 SeitenViolence in Cartoons: The Effect of Media On Children: Alswaeer. MMaryan AlSwaeerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Superstitions in Indian Culture ExplainedDokument10 SeitenSuperstitions in Indian Culture ExplainedKamali SundarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human RightsDokument15 SeitenHuman RightsPhalongtharpa BhaichungNoch keine Bewertungen

- TA-IntroDokument20 SeitenTA-Introsaquib0863Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gender and EconomyDokument34 SeitenGender and EconomyDr. Nisanth.P.MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Economy: Mobilizing ResourcesDokument4 SeitenIndian Economy: Mobilizing ResourcesTarique FaridNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cash Transactions Approach To MoneyDokument8 SeitenCash Transactions Approach To MoneyAppan Kandala Vasudevachary100% (2)

- Problem of Brain Drain in IndiaDokument3 SeitenProblem of Brain Drain in IndiaHardik PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional and Safeguards Provide To The Vulnerable Groups in IndiaDokument29 SeitenConstitutional and Safeguards Provide To The Vulnerable Groups in IndiaAnonymous H1TW3YY51KNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of NGOs in IndiaDokument17 SeitenRole of NGOs in IndiatrvthecoolguyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chanakya National Law UniversityDokument36 SeitenChanakya National Law Universityshubham kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judicial Review of Administrative Discretion PDFDokument44 SeitenJudicial Review of Administrative Discretion PDFAmanKumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in IndiaDokument25 SeitenBureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in Indiachandan8181Noch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Globalisation on Indian Stock MarketDokument27 SeitenImpact of Globalisation on Indian Stock MarketNadeem Lone0% (3)

- Criminology Edwin Sutherland Behavior: Sutherland's Theory of Differential AssociationDokument3 SeitenCriminology Edwin Sutherland Behavior: Sutherland's Theory of Differential AssociationkeshavllmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rethinking Rural DevelopmentDokument31 SeitenRethinking Rural Developmentomairbodla100% (2)

- The AK Model of New Growth Theory Is The Harrod - Domar Growth EquationDokument10 SeitenThe AK Model of New Growth Theory Is The Harrod - Domar Growth EquationAmaru Fernandez OlmedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evs Project - NOISE POLLUTION LAWDokument13 SeitenEvs Project - NOISE POLLUTION LAWAnanya YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- POCSO ACT PaperDokument21 SeitenPOCSO ACT PaperVishwam Kumar100% (1)

- Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Indian Higher Education Issues and Challenges-29Dokument11 SeitenRole of Corporate Social Responsibility in Indian Higher Education Issues and Challenges-29bhartiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amit Icl 123Dokument9 SeitenAmit Icl 123amit100% (1)

- 3 Ghurye On TribeDokument3 Seiten3 Ghurye On Tribekishorebharath100% (7)

- Assessing The Potential Impact of The African Continental Free Trade Area On Least Developed Countries A Case Study of EthiopiaDokument85 SeitenAssessing The Potential Impact of The African Continental Free Trade Area On Least Developed Countries A Case Study of Ethiopiahabtamu100% (1)

- Corruption Undermines Good Governance and DevelopmentDokument3 SeitenCorruption Undermines Good Governance and DevelopmentIsha RaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Good Lie: Movie ReviewDokument8 SeitenThe Good Lie: Movie ReviewSharmishtha BhardeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Term Paper in Research Final LastDokument7 SeitenTerm Paper in Research Final LastNarayan Kumar GhimireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central University of South BiharDokument17 SeitenCentral University of South BiharRajeev RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rural India Gandhi, Nehru and AmbedkarDokument12 SeitenRural India Gandhi, Nehru and AmbedkarMarcos MorrisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friedman - On Legal DevelopmentDokument55 SeitenFriedman - On Legal DevelopmentJorge GonzálezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijhss - Economic Thought of Pt. Deen Dayal UpadhyayaDokument4 SeitenIjhss - Economic Thought of Pt. Deen Dayal Upadhyayaiaset123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Peter DruckerDokument16 SeitenPeter Druckerflorin_ciureaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capability Approach - NotesDokument4 SeitenCapability Approach - NotesneelimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Port TrustDokument3 SeitenPort TrustParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group Decision Supportsystems G DssDokument10 SeitenGroup Decision Supportsystems G DssParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of HR MangersDokument1 SeiteRole of HR MangersParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Components of Marketing PlanDokument10 SeitenComponents of Marketing PlanParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data WarehouseDokument169 SeitenData WarehouseParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 34AdMediaDokument12 Seiten5 34AdMediaEr Siraj AzamNoch keine Bewertungen

- MM ApproachDokument5 SeitenMM ApproachParihar Babita100% (1)

- Water ConservationDokument57 SeitenWater ConservationParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authority Vs PowerDokument3 SeitenAuthority Vs PowerParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PMDokument20 SeitenPMAmrita Prashant IyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meaning Nature Scope Levels of ManagementDokument61 SeitenMeaning Nature Scope Levels of ManagementParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Warehouse Data Mart: Elahe SoroushDokument27 SeitenData Warehouse Data Mart: Elahe SoroushParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Line Staff RelationshipDokument6 SeitenLine Staff RelationshipParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chain of CommandDokument2 SeitenChain of CommandParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics in Advertising and Marketing: Presenting byDokument54 SeitenEthics in Advertising and Marketing: Presenting byParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data WarehousingDokument49 SeitenData WarehousingParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stratgc and Oprtnal ContrlDokument6 SeitenStratgc and Oprtnal ContrlParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AssumptionDokument8 SeitenAssumptionParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic ChoiceDokument43 SeitenStrategic ChoiceParihar Babita100% (1)

- Retail ManagementDokument18 SeitenRetail ManagementParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DMLLLDokument60 SeitenDMLLLParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- OD - InterventionsDokument26 SeitenOD - InterventionsGaurav PareekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Day 8Dokument51 SeitenDay 8Parihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes of SihrmDokument11 SeitenNotes of SihrmParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Mining TechniquesDokument16 SeitenData Mining TechniquesParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSR AsgnmtDokument15 SeitenCSR AsgnmtParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training and Development of Employees:: Importamt ProjectDokument18 SeitenTraining and Development of Employees:: Importamt ProjectParihar BabitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edward Halll T StudyDokument3 SeitenEdward Halll T StudyParihar Babita50% (2)

- Project Employee Training DevelopmentDokument15 SeitenProject Employee Training DevelopmentHimanshu KshatriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plato Girls PDFDokument30 SeitenPlato Girls PDFJohn Reigh CatipayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank For Human Sexuality 3rd Edition HockDokument36 SeitenTest Bank For Human Sexuality 3rd Edition HockLily Rector100% (31)

- Re-Envisioning Higher Education For A Post-Pandemic World: Apprehensions, Challenges and ProspectsDokument4 SeitenRe-Envisioning Higher Education For A Post-Pandemic World: Apprehensions, Challenges and Prospectswafaa elottriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of School Culture in LearningDokument8 SeitenThe Role of School Culture in LearningLepoldo Jr. RazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Example CVDokument2 SeitenExample CVMarta HarveyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diamond Doll Application 2012-2013Dokument4 SeitenDiamond Doll Application 2012-2013abby_zimbelman7498Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment Submission and AssessmentDokument5 SeitenAssignment Submission and AssessmentMarissa ZdianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECA Impact on Student PerformanceDokument15 SeitenECA Impact on Student PerformanceMichael Agustin0% (1)

- Grade 7-10 MathematicsDokument18 SeitenGrade 7-10 MathematicsChierynNoch keine Bewertungen

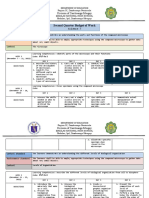

- Second Quarter Budget of Work Grade 7 - ScienceDokument6 SeitenSecond Quarter Budget of Work Grade 7 - ScienceRONNEL GALVANONoch keine Bewertungen

- Key Educational Theories and PhilosophiesDokument2 SeitenKey Educational Theories and PhilosophiesLordced SimanganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Esa Unggul University FacultiesDokument17 SeitenEsa Unggul University FacultiesYeni RahmawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum VitaeDokument5 SeitenCurriculum VitaeNiadika Ayu PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- St. Jude Parish School, Inc. Trece Martires City, Cavite: Certificate of AppearanceDokument6 SeitenSt. Jude Parish School, Inc. Trece Martires City, Cavite: Certificate of AppearanceAfia TawiahNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECE213 Socioemotional Development Children1Dokument16 SeitenECE213 Socioemotional Development Children1NUR HABIBAH BT YUSUFNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building A Future On A Foundation of Excellence: Division of Davao CityDokument2 SeitenBuilding A Future On A Foundation of Excellence: Division of Davao CityMike ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moreta Supervisor Assessment PaperDokument4 SeitenMoreta Supervisor Assessment Paperapi-396771461Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tuguegarao City, Cagayan 3500: St. Paul University PhilippinesDokument58 SeitenTuguegarao City, Cagayan 3500: St. Paul University Philippinesmarchelly simon0% (1)

- Adobe Scan 29 Nov 2023Dokument8 SeitenAdobe Scan 29 Nov 2023mikemwale5337Noch keine Bewertungen

- Welder ResumeDokument2 SeitenWelder ResumeTapas PalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schools Division Pre-Test Item AnalysisDokument6 SeitenSchools Division Pre-Test Item AnalysisHershey MonzonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dem CV PDFDokument1 SeiteDem CV PDFDanica Emily ManalotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan GonzaloDokument2 SeitenLesson Plan Gonzaloapi-252176454Noch keine Bewertungen

- Intellectual Disability Sample Assessment ReportDokument6 SeitenIntellectual Disability Sample Assessment ReportXlian Myzter YosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Application MaineDokument12 SeitenFirst Application MaineqjtxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Engineering Student ResumeDokument4 SeitenCivil Engineering Student ResumeFara AsilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracer Study Business MarketingDokument5 SeitenTracer Study Business MarketingXavel Zang100% (1)

- The Dual Training System in The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenThe Dual Training System in The PhilippinesCHARM BARCELONoch keine Bewertungen

- Script Closing ProgramDokument4 SeitenScript Closing Programshelley llamoso100% (3)