Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Oligopoly For MPA

Hochgeladen von

Ashraf Uz Zaman0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

59 Ansichten41 SeitenOligopoly for MPA (1)

Originaltitel

Oligopoly for MPA (1)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PPTX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenOligopoly for MPA (1)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PPTX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

59 Ansichten41 SeitenOligopoly For MPA

Hochgeladen von

Ashraf Uz ZamanOligopoly for MPA (1)

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PPTX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 41

Oligopoly for MPA

• If you go to a store to buy tennis balls, it is likely

that you will come home with one of four brands:

Wilson, Penn, Dunlop or Spalding.

• These four companies make almost all of the

tennis balls sold in the US.

• Together, these firms determine the quantity of

tennis balls produced and given the market

demand curve, the price at which tennis balls are

sold.

• How can we describe the market for tennis balls?

• The market for tennis balls fits neither the

competitive nor the monopoly model.

• Competition and monopoly are extreme forms of

market structure.

• Competition occurs when there are many firms in

a market offering essentially identical product;

• Monopoly occurs when there is only one firm in a

market.

• It is natural to start the study of industrial

organization with these polar cases, for they are

easiest cases to understand.

• Yet many industries, including the tennis-ball

industry, fall somewhere between these two

extremes.

• Firms in these industries have competitors but at

the same time, do not face so much competition

that they are price takers.

• Economists call this situation imperfect

competition.

• The essence of an oligopolistic market is that

there are only a few sellers.

• As a result the actions of seller in the market

can have a large impact on the profits of all

the other sellers.

• That is oligopolistic firms are interdependent

in a way that competitive firms are not.

Between Monopoly and Monopolistic

Competition

Markets with only a few sellers

• Because an oligopolistic market has only a small

group of sellers, a key feature of oligopoly is the

tension between co-operation and self-interest.

• The group of oligopolists is best off co-operating

and acing like a monopolist-producing a small

quantity of output and charging a price above

MC.

• Yet because each oligopolist cares about only its

own profit, there are powerful incentives at work

that hinder a group of firms from maintaining the

monopoly outcome.

A Duopoly Example

• To understand the behavior of oligopolist let’s

consider an oligopoly with two members

called a duopoly.

• Duopoly is the simplest type of oligopoly.

• Oligopoly with three or more members face

the same problems as oligopolies with only

two members, so we do not lose much by

starting with the case of duopoly.

• Imagine a town in which only two residents----

Jack and Jill—own wells that produce water safe

for drinking.

• Each Saturday Jack and Jill decide how many

gallons of water to pump, bring the water to

town, and sell it for whatever price the market

will bear.

• To keep things simple, suppose that Jack and Jill

can pump as much water as they want without

cost.

• That is MC of water equals zero.

• Table 1 shows town’s demand schedule for

water.

• The first column shows the total quantity

demanded and second column shows the

price.

• If the well owners sell a total of 10 gallons of

water, water goes for $110 a gallon.

• Quantity Price TR

• 0 $120 $0

• 10 110 1100

• 20 100 2000

• 30 90 2700

• 40 80 3200

• 50 70 3500

• 60 60 3600

• 70 50 3500

• 80 40 3200

• 90 30 2700

• 100 20 2000

• 110 10 1100

• 120 0 0

• If the two well owners sell a total of 10 gallons

of water, water goes for $110 a gallon.

• If they sell a total of 20 gallons, the price falls

to $100 a gallon.

• And so on.

• If you graphed these two columns of numbers,

you would get a standard downward sloping

demand curve.

• The last column shows TR from the sale of

water.

• Because there is no cost of pumping water,

the TR of the two producers equals their total

profit.

• Let us consider how the organisation of the

town’s water industry affects the price of

water and the quantity of water sold.

Competition, Monopolies and Cartels

• Consider first what would happen if the

market for water were perfectly competitive.

• In a competitive market, the production

decisions of each firm drive price equal to MC.

• In the market for water, MC is zero.

• Thus under competition, the equilibrium price

of water would be zero and the equilibrium

quantity would be 120 gallons.

• The price of water would reflect the cost of

producing it and the efficient quantity of water

would be produced and consumed.

• Now consider how a monopoly would behave.

• Table 1 shows that total profit is maximized at a

quantity of 60 gallons and a price of $60 a gallon.

• A profit-maximizing monopolist, therefore, would

produce this quantity and charge this price.

• As is standard for monopolies, price would

exceed MC.

• The result would be inefficient, for the

quantity of water produced and consumed

would fall short of the socially efficient level of

120 gallons.

• What outcome should we expect from our

duopolists?

• One possibility is that Jack and Jill get together

and agree on the quantity of water to produce

and the price to charge for it.

• Such an agreement among firms over

production and price is called collusion and

the group of firms acting in unison is called a

cartel.

• Once a cartel is formed, the market is in effect

served by a monopoly.

• That is if Jack and Jill were to collude, they

would agree on monopoly outcome because

that outcome maximizes the total profit that

the producers can get from the market.

• Our two producers would produce a total of

60 gallons which would be sold at a price of

$60 a gallon.

• Once again, price exceeds MC and the

outcome is socially inefficient.

• A cartel must agree not only on the total level of

production but also on the amount produced by each

member.

• In our case, Jack and Jill must agree how to split

between themselves the monopoly production of 60

gallons.

• Each member of the cartel will want a larger share of

the market because a larger market share means larger

profit.

• If Jack and Jill agreed to split the market equally, each

would produce 30 gallons, the price would be $60 a

gallon and each would get a profit of $1800.

The equilibrium for an oligopoly

• Although oligopolies would like to form cartels and

earn monopoly profits, often that is not possible.

Antitrust laws prohibit explicit agreements among

oligopolists as a matter of public policy.

• In addition, squabbling among cartel members over

how to divide the profit in the market sometimes

makes agreement among them impossible.

• Let us therefore consider what happens if Jack and Jill

decide separately how much water to produce.

• At first one might expect jack and Jill to reach

the monopoly outcome on their own, for this

outcome maximizes their joint profit.

• In the absence of a binding agreement,

however, the monopoly outcome is unlikely.

• To see why, imagine that jack expects Jill to

produce only 30 gallons (half of the monopoly

quantity).

• Jack would reason as follows:

• “I could produce 30 gallons as well.

• In this case, a total of 60 gallons of water

would be sold at a price of $60 a gallon.

• My profit would be $1800 (30gallons*$60 a

gallon).

• Alternatively, I could produce 40 gallons.

• In this case, a total of 70 gallons of water

would be sold at a price of $50 a gallon.

• My profit would be $2000 ($40gallons X $50 a

gallon).

• Even though total profit in the market would fall,

my profit would be higher because I would have a

larger share of the market.

• Of course, Jill might reason the same way.

• If so jack and Jill would each bring 40 gallons in

the town.

• Total sales would be 80 gallons, and the price

would fall to $40.

• If the duopolists individually pursue their self-

interest when deciding how much to produce,

they produce a total quantity greater than the

monopoly quantity, charge a price lower than the

monopoly price, and earn total profit less than

the monopoly profit.

• Although the logic of self-interest increases the

duopoly’s output above monopoly level, it does

not push the duopolists to reach the competitive

allocation.

• Consider what happens when each duopolist

is producing 40 gallons.

• The price is $40 and each duopolist makes a

profit of $1600.

• In this case, Jack’s self-interested logic leads to

a different conclusion.

• “Right now, my profit is $1600. Suppose I

increase my production to 50 gallons.

• In this case, a total of 90 gallons of water would

be sold, and the price would be $30 a gallon.

• Then my profit would be $1500.

• Rather than increasing production and driving

down the price, I am better off keeping my

production at 40 gallons.

• The outcome in which jack and Jill each produce

40 gallon looks like some sort of equilibrium.

• In fact, this outcome is called a Nash equilibrium.

• A Nash equilibrium is a situation in which

economic participants interacting with one

another each choose their best strategy given the

strategies the others have chosen.

• In this case, given that Jill is producing 40 gallons,

the best strategy for Jack is to produce 40 gallons.

• Similarly, given that Jack is producing 40 gallons,

the best strategy for Jill is to produce 40 gallons.

• Once they reach this Nash equilibrium, neither

Jack nor Jill has an incentive to make a different

decision.

• This example illustrates the tension between

cooperation and self-interest.

• Oligopolists would be better off cooperating

and reaching the monopoly outcome and

maximizing their joint profit.

• Each oligopolist is tempted to raise production

and capture a larger share of the market.

• As each tries to do this, total production rises

and the price falls.

• At the same time, self-interest does not drive

the market all the way to the competitive

outcome.

• Like monopolists, oligopolists are aware that

increases in the amount they produce reduce

the price of their product.

• Therefore they stop short of following the

competitive firm’s rule of producing upto the

point where price equals MC.

• In summary, when firms in an oligopoly

individually choose production to maximize

profit, they produce a quantity of output

greater than the level produced by monopoly

and less than the level produced by

competition.

• The oligopoly price is less than the monopoly

price but greater than competitive price.

How the size of an oligopoly affects

market outcome

• We can use the insights from this analysis of

duopoly to discuss how the size of an oligopoly is

likely to affect the outcome in a market.

• Suppose for example, that John and Joan

suddenly discover water sources on their

property and join jack and jill in the water

oligopoly.

• The demand schedule remains the same, but

now more producers are available to satisfy this

demand.

• How would an increase in the number of sellers

from two to four affect the price and quantity of

water in the town?

• If the sellers of water could form a cartel, they

would once again try to maximize total profit by

producing the monopoly quantity and charging

the monopoly price.

• Just as when there were only two sellers, the

members of cartel would need to agree on

production levels for each member and find some

way to enforce the agreement.

• As the cartel grows larger, however, the

outcome is less likely.

• Reaching and enforcing an agreement become

more difficult as the size of the group

increases.

• If the oligopolists do not form a cartel----

perhaps because the antitrust laws prohibit it-

--they must each decide on their own how

much water to produce.

• To see how the increase in the number of sellers

affects the outcome, consider the decision facing

each seller.

• At any time each well owner has the option to

raise production by 1 gallon.

• In making decision the well owner weighs two

effects:

The output effect: because price is above MC,

selling one more gallon of water at the going

price will raise profit.

• The price effect: Raising production will increase

the total amount sold, which will lower the price

of water and lower the profit on all the other

gallons sold.

• If the output effect is larger than the price effect,

the well owner will increase production.

• If the price effect is larger than output effect, the

owner will not raise production. In fact , it will be

profitable to reduce production.

• Each oligopolist continues to increase production

until these two marginal effects exactly balance,

taking the other firm’s production as given.

• Now consider how the number of firms in the

industry affects marginal analysis of each

oligopolist.

• The larger the number of sellers, the less

concerned each seller is about its own impact on

the market price.

• That is as the oligopoly grows in size, the

magnitude of the price effect falls.

• When the oilgopoly grows very large, the price

effect disappears altogether, leaving only the

output effect.

• In this extreme case, each firm in the oligopoly

increases production as long as price is above

MC.

• We can now see that a large oligopoly is

essentially a group of competitive firms. A

competitive firm considers only the output

effect when deciding how much to produce:

because a competitive firm is a price taker, the

price effect is absent.

• Thus as the number of sellers in an oligopoly

grows larger, an oligopolistic market looks

more and more like a competitive market.

• The price approaches the MC and the quantity

produced approaches the socially efficient level.

• The analysis of oligopoly offers a new perspective

on the effects of international trade.

• Imagine that Toyota and Honda are the only

automakers in Japan, Volkswagen and BMW are

the only automakers in Germany and Ford and

General Motors are the only automakers in the

US.

• If these nations prohibited IT in autos, each

would have an auto oligopoly with only

members and the market outcome would

likely depart substantially from the

competitive ideal.

• With IT, however, the car market is a world

market and the oligopoly in this example has

six members.

• Allowing free trade increases the number of

producers from which each consumer can

choose and this increased competition keeps

prices closer to MC.

• Thus the theory of oligopoly provides another

reason why all countries can benefit from free

trade.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- VC AndrewsDokument3 SeitenVC AndrewsLesa O'Leary100% (1)

- Chapter 24 - The Solar SystemDokument36 SeitenChapter 24 - The Solar SystemHeather Blackwell100% (1)

- OligopolyDokument17 SeitenOligopolyraviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly: ECON 0100Dokument51 SeitenMonopolistic Competition and Oligopoly: ECON 0100hussnain tararNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17 OligopolyDokument46 Seiten17 OligopolyDhaval Pandya0% (1)

- C17 Edisi 5Dokument36 SeitenC17 Edisi 5Anugerah BagusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Between Monopoly and Perfect Competition: OligopolyDokument7 SeitenBetween Monopoly and Perfect Competition: Oligopolymehmet nedimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 17 - OligopolyDokument35 SeitenChapter 17 - OligopolyTrần Ngọc Mỹ UyênNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 17 - OligopolyDokument41 SeitenChapter 17 - Oligopolycarysma25Noch keine Bewertungen

- SS 132: Microeconomics SS 132: Microeconomics: Oligopoly OligopolyDokument20 SeitenSS 132: Microeconomics SS 132: Microeconomics: Oligopoly Oligopolymuhammad atta ur rehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sesi9 Oligopoly1Dokument30 SeitenSesi9 Oligopoly1aedsutanNoch keine Bewertungen

- OligopolyDokument18 SeitenOligopolySu Sint Sint HtwayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market EquilibriumDokument22 SeitenMarket EquilibriumananthanvaikomNoch keine Bewertungen

- OligopolyDokument21 SeitenOligopolyArsalan Mushtaq0% (1)

- Oligopoly-WPS OfficeDokument12 SeitenOligopoly-WPS OfficeLamillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11 OligipolyDokument12 SeitenChapter 11 OligipolyIsya LolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 Oligopoly 2022Dokument28 Seiten11 Oligopoly 2022Pletea GeorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- OligopolyDokument3 SeitenOligopolyAzlan PspNoch keine Bewertungen

- ITO - Theory of IPEDokument38 SeitenITO - Theory of IPEstarsoflifefliesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lec 19Dokument11 SeitenLec 19vinibarcelosNoch keine Bewertungen

- OLIGOPOLYDokument38 SeitenOLIGOPOLYMei Mei KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- $micro IIDokument224 Seiten$micro IIanesahmedtofik932Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 16-Oligopoly-PDokument27 SeitenChapter 16-Oligopoly-PNgan DinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- DD209: Running The Economy: Tutorial 4: February 2017Dokument30 SeitenDD209: Running The Economy: Tutorial 4: February 2017Zannatul FerdausNoch keine Bewertungen

- Set 10 Internartional Market and International TradeDokument31 SeitenSet 10 Internartional Market and International Trade黄一正Noch keine Bewertungen

- ECO 365 Final Exam Guide (New, 2017) : For More Classes VisitDokument36 SeitenECO 365 Final Exam Guide (New, 2017) : For More Classes Visitking rockNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lect 16Dokument42 SeitenLect 16rajendra kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monopolistic CompetitionDokument51 SeitenMonopolistic Competitionanon_800440945Noch keine Bewertungen

- BUAD 425 Chapter 8 - 2023-24 (Student Version)Dokument29 SeitenBUAD 425 Chapter 8 - 2023-24 (Student Version)jordan.murphy3333Noch keine Bewertungen

- Microeconomics Adel LauretoDokument105 SeitenMicroeconomics Adel Lauretomercy5sacrizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Price & Output Determination in Monopoly & Imperfect MarketsDokument11 SeitenPrice & Output Determination in Monopoly & Imperfect Marketssajal agarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- MonopolyDokument26 SeitenMonopolyhasanimam mahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumers, Producers, and The Efficiency of BusinessDokument22 SeitenConsumers, Producers, and The Efficiency of BusinessAriana Faye CastillanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2 - The Market Forces of Supply & DemandDokument47 SeitenChapter 2 - The Market Forces of Supply & DemandTonmoy (123011100)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Monopoly: Instructor: Ghislain Nono GueyeDokument24 SeitenMonopoly: Instructor: Ghislain Nono Gueyedcttd68kgdNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Determination of Demand For Goods and ServicesDokument30 SeitenThe Determination of Demand For Goods and ServicesRichie ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Business and Globalisation 311 MANEL: Week 2 - Session 1Dokument27 SeitenInternational Business and Globalisation 311 MANEL: Week 2 - Session 1Cornea CristianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market StructureDokument77 SeitenMarket StructureVishal SiddheshwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer and Producer Surplus: AP Economics Mr. BordelonDokument46 SeitenConsumer and Producer Surplus: AP Economics Mr. BordelonS TMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Objectives For Chapter 8 Price Floors and Ceilings: "Black Market" and "Gray Market"Dokument8 SeitenObjectives For Chapter 8 Price Floors and Ceilings: "Black Market" and "Gray Market"Sadaf KushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contrast The Most Important Conditions: Review QuestionDokument28 SeitenContrast The Most Important Conditions: Review QuestionJuvenal Rafael Mercado CanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demand and Its DeterminantsDokument14 SeitenDemand and Its Determinantsapi-26241693457% (7)

- Unit 4 MonopolyDokument27 SeitenUnit 4 MonopolySuresh Kumar100% (1)

- OligopolyDokument11 SeitenOligopolyFachrizal WomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic LiberalismDokument8 SeitenEconomic LiberalismSHEKINAHFAITH REQUINTELNoch keine Bewertungen

- Game Theory and Oligopoly Game Theory and OligopolyDokument18 SeitenGame Theory and Oligopoly Game Theory and OligopolyShobha MukherjeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ibm 3Dokument30 SeitenIbm 3Nasr MohammedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Micro Ch16 PresentationDokument38 SeitenMicro Ch16 PresentationErsin TukenmezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patterns and Trends in International TradeDokument16 SeitenPatterns and Trends in International TradeManisha SahuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ch16 OligopolyDokument32 SeitenCh16 OligopolyhazrezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MonopolyDokument30 SeitenMonopolyHussain HajiwalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monopoly And-OligopolyDokument36 SeitenMonopoly And-OligopolykushalyadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic 5Dokument12 SeitenEconomic 5peter banjaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ME Class Day 3 N 4Dokument58 SeitenME Class Day 3 N 4Harini BaskaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mankiw Week 7Dokument14 SeitenMankiw Week 7asahi's gfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perfect CompDokument24 SeitenPerfect CompSS CreationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly: Mankiv CH 15, 16, 17 Brue CH 10, 11Dokument21 SeitenMonopolistic Competition and Oligopoly: Mankiv CH 15, 16, 17 Brue CH 10, 11Muhammad AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSM5200 Session14 OligopolyDokument15 SeitenMSM5200 Session14 OligopolyAarushi PawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 12Dokument27 SeitenChapter 12Sajid BhatNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Blending and Compounding - Liquors and WinesVon EverandThe Art of Blending and Compounding - Liquors and WinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumers' Cooperative Societies in New York StateVon EverandConsumers' Cooperative Societies in New York StateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Positive Accounting TheoryDokument47 SeitenPositive Accounting TheoryAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting Theory - IntroductionDokument13 SeitenAccounting Theory - IntroductionAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of New CF 2018Dokument23 SeitenSummary of New CF 2018Ashraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detecting Accounting Fraud - The Case of Let's Gowex SA: Document de RecercaDokument47 SeitenDetecting Accounting Fraud - The Case of Let's Gowex SA: Document de RecercaAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Word of Mouth Marketing of Motorcycle ProductDokument9 SeitenHow Word of Mouth Marketing of Motorcycle ProductAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qualitative Research Methods: Ted EthnographyDokument28 SeitenQualitative Research Methods: Ted EthnographyAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSE Limited, Plot No. C/1, G Block, Mumbai - 400 001Dokument28 SeitenBSE Limited, Plot No. C/1, G Block, Mumbai - 400 001Ashraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- IPO Note On Crystal Insurance Limited (CRYSTALINS) PDFDokument8 SeitenIPO Note On Crystal Insurance Limited (CRYSTALINS) PDFAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh Food Situation Report: January-March, 2019 Volume-116Dokument6 SeitenBangladesh Food Situation Report: January-March, 2019 Volume-116Ashraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lo 2+3 - 1: Legitimacy Theory: 1 Created by DR G. L. Ilott, Cquniversity AustraliaDokument9 SeitenLo 2+3 - 1: Legitimacy Theory: 1 Created by DR G. L. Ilott, Cquniversity AustraliaAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- IPO Profile of Robi Axiata Limited - PDFDokument7 SeitenIPO Profile of Robi Axiata Limited - PDFAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh Food Situation Report: July-September, 2015 Volume-102Dokument6 SeitenBangladesh Food Situation Report: July-September, 2015 Volume-102Ashraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Equity Insight On Olympics Industries LTD PDFDokument7 SeitenEquity Insight On Olympics Industries LTD PDFAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Equity Insight On Olympics Industries LTD PDFDokument7 SeitenEquity Insight On Olympics Industries LTD PDFAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Equity Valuation Report On Confidence Cement Limited PDFDokument19 SeitenEquity Valuation Report On Confidence Cement Limited PDFAshraf Uz ZamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Capital Management: Group - 4 Jahnvi Jethanandini Shreyasi Halder Siddhartha Bayye Sweta SarojDokument5 SeitenStrategic Capital Management: Group - 4 Jahnvi Jethanandini Shreyasi Halder Siddhartha Bayye Sweta SarojSwetaSarojNoch keine Bewertungen

- A2 UNIT 5 Culture Teacher's NotesDokument1 SeiteA2 UNIT 5 Culture Teacher's NotesCarolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

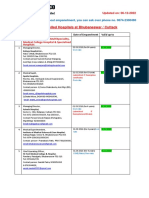

- Empanelled Hospitals List Updated - 06-12-2022 - 1670482933145Dokument19 SeitenEmpanelled Hospitals List Updated - 06-12-2022 - 1670482933145mechmaster4uNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nyamango Site Meeting 9 ReportDokument18 SeitenNyamango Site Meeting 9 ReportMbayo David GodfreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- TAC42055 - HO01 Edition I2.0: Section 1 Module 1 Page 1Dokument69 SeitenTAC42055 - HO01 Edition I2.0: Section 1 Module 1 Page 1matheus santosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gmail - ICICI BANK I PROCESS HIRING FOR BACKEND - OPERATION PDFDokument2 SeitenGmail - ICICI BANK I PROCESS HIRING FOR BACKEND - OPERATION PDFDeepankar ChoudhuryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Donnan Membrane EquilibriaDokument37 SeitenDonnan Membrane EquilibriamukeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal 1 Ieevee LPF PDFDokument4 SeitenJurnal 1 Ieevee LPF PDFNanda SalsabilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- B0187 B0187M-16Dokument9 SeitenB0187 B0187M-16Bryan Mesala Rhodas GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beautiful SpotsDokument2 SeitenBeautiful SpotsLouise Yongco100% (1)

- 13507Dokument5 Seiten13507Abinash Kumar0% (1)

- Autodesk Nastran In-CAD PDFDokument43 SeitenAutodesk Nastran In-CAD PDFFernando0% (1)

- Brochure GM Oat Technology 2017 enDokument8 SeitenBrochure GM Oat Technology 2017 enArlette ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atlascopco XAHS 175 DD ASL Parts ListDokument141 SeitenAtlascopco XAHS 175 DD ASL Parts ListMoataz SamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- RESEARCH 10 Module 1 Lesson 1 (WEEK 1-2)Dokument5 SeitenRESEARCH 10 Module 1 Lesson 1 (WEEK 1-2)DennisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Em FlexicokingDokument8 SeitenEm FlexicokingHenry Saenz0% (1)

- Managemant PrincipleDokument11 SeitenManagemant PrincipleEthan ChorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Practical Eden Swithenbank Graded PeDokument7 SeitenDesign Practical Eden Swithenbank Graded Peapi-429329398Noch keine Bewertungen

- Simon Fraser University: Consent and Release FormDokument1 SeiteSimon Fraser University: Consent and Release FormpublicsqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annex To ED Decision 2013-015-RDokument18 SeitenAnnex To ED Decision 2013-015-RBurse LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- JCIPDokument5 SeitenJCIPdinesh.nayak.bbsrNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Process Reference Model For Claims Management in Construction Supply Chains The Contractors PerspectiveDokument20 SeitenA Process Reference Model For Claims Management in Construction Supply Chains The Contractors Perspectivejadal khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment 4 PDFDokument10 SeitenAssessment 4 PDFAboud Hawrechz MacalilayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Negative Feedback AmplifierDokument31 SeitenNegative Feedback AmplifierPepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taxation Law 1Dokument7 SeitenTaxation Law 1jalefaye abapoNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is A Fired Heater in A RefineryDokument53 SeitenWhat Is A Fired Heater in A RefineryCelestine OzokechiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study To Find Tank Bulging, Radial Growth and Tank Settlement Using API 650Dokument15 SeitenCase Study To Find Tank Bulging, Radial Growth and Tank Settlement Using API 650Jafer SayedNoch keine Bewertungen

- R15 Understanding Business CyclesDokument33 SeitenR15 Understanding Business CyclesUmar FarooqNoch keine Bewertungen