Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

CT Fallacies

Hochgeladen von

Vanka Ramesh0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

83 Ansichten24 SeitenOriginaltitel

CT Fallacies.ppt

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PPT, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PPT, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

83 Ansichten24 SeitenCT Fallacies

Hochgeladen von

Vanka RameshCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PPT, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 24

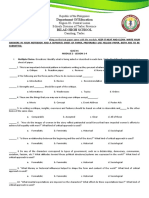

Fallacies of Relevance

All Fallacies of Relevance share the

common problem of appealing to features

that are irrelevant for the evaluation of a

line of reasoning or evidence—they appeal

to factors that do not speak to the truth of

a position or the quality of evidence for it.

Ad Verecundiam (Improper Appeal

to Authority)

Appeal to someone as an authority in

areas where they lack relevant expertise

Appeals to Authority Continued

Appeals to authorities that have a

recognizable bias

Appeals to Authority Continued

Appeals to law or religious principles as

finalizing matters of truth

Ad Populum

Appeal to mass belief, mass sentiment or

mass commitment

False Consensus: presentation of a

controversial viewpoint as if it were

received knowledge.

Ad Hominem

Literally: “against the man”

Replaces evaluation of ideas or evidence

with a personal attack

Ad Hominem Circumstantial: group-based

version of the Ad Hominem

Ad Hominem is not fallacious if it is

relevant to evaluating a line of reasoning

Andrea Dworkin

Tu Quoque

Literally: “You too”

Charge of hypocrisy used to reject the

truth of a claim

Ad Baculum

Appeal to force or other coercion to obtain

assent/agreement without offering

evidence or reasoning

Ad Misericordiam (Appeal to Pity)

Appeal to our emotions, especially sympathy or pity, to

convince without argument.

Ad Ignorantiam (Appeal to

Ignorance)

Involves a claim being declared true or

false because its denial can’t be proven

There may be some cases where a lack of

evidence IS evidence

Fallacies of Presumption

All fallacies of presumption share the

common failing of appealing to

unwarranted assumptions that, when

revealed, undermine the strength of the

reasoning offered

Hasty Generalization

Hasty Generalizations occur when an

inference is made from a small or atypical

sample

Availability Heuristic (or Bias)

We tend to overestimate how likely an

event is to occur based on how easy it is

to recall to memory

Events that are startling, emotionally

evocative or otherwise salient will be

recalled easier

Confirmation Bias

Our tendency to search out confirming

evidence and ignore possible

disconfirming evidence

Includes our tendency to treat

disconfirming evidence more critically than

confirming evidence

Fallacy of Misleading Vividness

Overlooking strong evidence due to a

salient counterexample

Fallacy of Accident

Reverse of the Hasty Generalization

Involves applying a general rule to a

recognizably atypical or exceptional case

Begging the Question (Circularity)

Circular reasoning assumes what it is out

to prove; the evidence already assumes

the truth of the conclusion

Circular arguments may be deductively

valid (and sound!), but are still fallacious

Indirect Circularity

Appealing to evidence that only those who

agree with your conclusion would accept

as evidence; “preaching to the choir”

Involves appeal to controversial evidence

that is not recognized as such

Unlike directly circular arguments, these

can be salvaged

Complex Question

A question loaded to generate a specific

answer

Related to question-begging in that an

answer is assumed

Framing Effect: the way the question is

“framed” affects what answers are given

Straw Man

Deliberate misrepresentation of an

opposing viewpoint; distorts or caricatures

for ease of refutation

Look for attributions of extreme views: this

is a red flag for a Straw Man

Look for attributions of absurd views: this

is a red flag for a Straw Man

Different from a Reductio argument

Bifurcation (aka False Dichotomy;

False Dilemma)

Artificial limitation of options; typically to 2

Often linked to other fallacies

Value Dichotomies: WE value x, while

THEY don’t

Slippery Slope

Predictive story without supporting evidence, or

where the only evidence is “common sense”

Connections in the story are assumed, not

demonstrated

Can be progressive (if we just do X, all these

great things will happen!) or gloom-and-doom (of

we do X, the sky will fall!)

Related to Golden Age Fallacy (things were so

much better in the past) and Utopian Fallacy

(things are so much better than they once were)

Slippery Slope continued

Predictive stories are never more certain

than their first step

This is because with each additional step

in the story that isn’t CERTAIN, the

likelihood that the whole story is true

DECREASES

The irony: the features that make a

slippery slope a good story undermine the

likelihood of the story’s truth

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Module 4 VerbsDokument34 SeitenModule 4 Verbsmarco medurandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essentials of A Position PaperDokument4 SeitenEssentials of A Position PaperJuan BagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Templates For Disagreeing, With ReasonsDokument2 SeitenTemplates For Disagreeing, With ReasonsCaroline RhudeNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Analysis of The Kalam Cosmological Argument by Al-GhazaliDokument11 SeitenA Critical Analysis of The Kalam Cosmological Argument by Al-Ghazalimmuraj313100% (1)

- Encyclopedia of Phenomenology PDFDokument777 SeitenEncyclopedia of Phenomenology PDFVero Cohen100% (4)

- 8 Process of Stylistic AnalysisDokument8 Seiten8 Process of Stylistic AnalysisAwais TareqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Different Errors Committed in Social Media.: Common Filipino FallaciesDokument45 SeitenDifferent Errors Committed in Social Media.: Common Filipino FallaciesJemimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FallaciesDokument3 SeitenFallacies123 456Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 6 (Introduction To Literary Criticism)Dokument55 SeitenModule 6 (Introduction To Literary Criticism)Erlinda RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review Rubric: Assignment Basics ArticlesDokument2 SeitenLiterature Review Rubric: Assignment Basics ArticlesReeds GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kierkegaard and PhenomenologyDokument27 SeitenKierkegaard and PhenomenologyVladimir CârlanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes in Interpreting Plato's DialoguesDokument27 SeitenNotes in Interpreting Plato's DialoguesElevic PernisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ideas General Introduction To Pure PhenomenologyDokument5 SeitenIdeas General Introduction To Pure PhenomenologyAndré ZanollaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic FallaciesDokument14 SeitenBasic Fallaciesem.jolayemiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis StatementsDokument3 SeitenThesis Statementsmslenihan100% (1)

- Rubric For DebateDokument1 SeiteRubric For DebatemsbakermathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Derrida and DeconstructionDokument5 SeitenDerrida and DeconstructionJovana Stojanovic100% (1)

- Writing A Position PaperDokument14 SeitenWriting A Position PaperMichele Taylor BauerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plagiarism Prevention Quiz QuestionsDokument8 SeitenPlagiarism Prevention Quiz Questionsramu0923Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper PowerpointDokument26 SeitenResearch Paper PowerpointHanna Sharleen FlorendoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Campus Journalism - A Course SyllabusDokument9 SeitenCampus Journalism - A Course Syllabuspark jiminNoch keine Bewertungen

- RW - CM 4 - Properties of A Well-Written Text IIDokument27 SeitenRW - CM 4 - Properties of A Well-Written Text IIvianne bonville simbulanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Education Bilad High SchoolDokument4 SeitenDepartment of Education Bilad High SchoolOrly GrospeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing An Editorial or Opinion ColumnDokument2 SeitenWriting An Editorial or Opinion ColumnTashfeen YousafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zahavi Dan Husserl S Phenomenology PDFDokument188 SeitenZahavi Dan Husserl S Phenomenology PDFManuel Pepo Salfate50% (2)

- The Noesis and NoemaDokument7 SeitenThe Noesis and NoemaAquamarine Ruby GoldmagentaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Death Constant Beyond Love AnalysisDokument4 SeitenDeath Constant Beyond Love AnalysisBetlee Ian Barraquias0% (1)

- COMFTF 08-B Logical Fallacies PPT (With Sound) Rev4!12!05Dokument64 SeitenCOMFTF 08-B Logical Fallacies PPT (With Sound) Rev4!12!05David F Maas100% (1)

- Arguments in Ordinary LanguageDokument5 SeitenArguments in Ordinary LanguageStephanie Reyes GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metrical Patterns PDFDokument5 SeitenMetrical Patterns PDFAlcel PascualNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elements of Fiction HandDokument18 SeitenElements of Fiction HandYuri PodmoroffNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Study of LogicDokument26 SeitenThe Study of LogicPatrick CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critique EssayDokument3 SeitenCritique EssayTaylor WeathersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay RubricDokument2 SeitenEssay RubricBrett ClendanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- LogicalFallaciesIntro ActivitiesDokument14 SeitenLogicalFallaciesIntro ActivitiesSyed Ghous Ali Shah100% (1)

- How To Study and Critique A SpeechDokument6 SeitenHow To Study and Critique A SpeechYouness Mohamed AmààchNoch keine Bewertungen

- FallaciesDokument10 SeitenFallaciesRed HoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative AnalysisDokument7 SeitenComparative Analysisapi-264701954Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pathos, Logos and EthosDokument2 SeitenPathos, Logos and EthosZnow BearNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rhetorical Strategies Quiz Final DraftDokument4 SeitenRhetorical Strategies Quiz Final Draftapi-394560871Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A MemoDokument13 SeitenHow To Write A MemoNoreen Joyce J. PepinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asian Debate FormatDokument7 SeitenAsian Debate FormatJonadine DyNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is An ArgumentDokument2 SeitenWhat Is An ArgumentAmir ShameemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analyzing ArgumentsDokument2 SeitenAnalyzing Argumentsapi-243228236Noch keine Bewertungen

- AVOIDING FALLACIES QR - SaifDokument16 SeitenAVOIDING FALLACIES QR - SaifjavidimsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Campuses: Hilltop - MH Del Pilar - Pallocan East - Pallocan West - Lipa Telephone Numbers: +63 43 723 1446 - 980 0041 Website: WWW - Ub.edu - PHDokument2 SeitenCampuses: Hilltop - MH Del Pilar - Pallocan East - Pallocan West - Lipa Telephone Numbers: +63 43 723 1446 - 980 0041 Website: WWW - Ub.edu - PHImeeh Esmeralda-AmandyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adjudication SeminarDokument18 SeitenAdjudication Seminarwahyu nurcahyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Descriptive Essay RubricDokument2 SeitenDescriptive Essay RubricMuhammad Fatih100% (1)

- Writing A Position PaperDokument21 SeitenWriting A Position PaperApril Mae AyawaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 2: Fiction and Creative NonfictionDokument13 SeitenLesson 2: Fiction and Creative NonfictionDaniella Ize GordolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colloquialism Examples in LiteratureDokument4 SeitenColloquialism Examples in Literaturemaiche amarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cainta Catholic College: Senior High School DepartmentDokument17 SeitenCainta Catholic College: Senior High School DepartmentAllan Santos SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay Introductions LP FinalDokument2 SeitenEssay Introductions LP Finalapi-294957224Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nathaniel HawthorneDokument2 SeitenNathaniel HawthorneAndreea ChirilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RJ Mock TrialDokument2 SeitenRJ Mock TrialHeather AultNoch keine Bewertungen

- African LiteratureDokument14 SeitenAfrican LiteratureCristell Mae LasinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On Literary CriticismDokument9 SeitenNotes On Literary CriticismLucky AnnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compare and Contrast Essay 023Dokument4 SeitenCompare and Contrast Essay 023api-293952433Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bibliography (Apa Format)Dokument11 SeitenBibliography (Apa Format)Karen Doblada AcuarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write News ReportDokument12 SeitenHow To Write News ReportMohsin RazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Persuasive WritingDokument1 SeitePersuasive Writingapi-260642329Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stasis Theory in Academic Writing - Student Slides 3Dokument11 SeitenStasis Theory in Academic Writing - Student Slides 3api-490608937Noch keine Bewertungen

- Interval ScaleDokument7 SeitenInterval ScaleGilian PradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Logical FallaciesDokument39 SeitenLogical FallaciesRufo Jawa100% (1)

- Reaction PaperDokument5 SeitenReaction PapermigoogooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Villarica Pawnshop V Sps GernaleDokument1 SeiteVillarica Pawnshop V Sps GernaleStella LynNoch keine Bewertungen

- CT FallaciesDokument24 SeitenCT FallaciespeterdrockNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fallacies of RelevanceDokument23 SeitenFallacies of RelevanceDaniels PicturesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition of An ArgumentDokument2 SeitenDefinition of An ArgumentJTupakNoch keine Bewertungen

- D Section Project TopicsDokument5 SeitenD Section Project TopicsSamaj SewaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Categorical Syllogisms2Dokument30 SeitenCategorical Syllogisms2May Anne BarlisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypothetico-Deductive Method: Parul Agarwal A001Dokument11 SeitenHypothetico-Deductive Method: Parul Agarwal A001محمد فهميNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mean Median ModeDokument36 SeitenMean Median ModeBijal PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- TTC Consciousness and Its Implications BibliographyDokument2 SeitenTTC Consciousness and Its Implications BibliographyGlenGrail100% (1)

- Logic and Critical ThinkingDokument57 SeitenLogic and Critical ThinkingBilisuma Amante100% (1)

- Phenomenology and Hermeneutic Phenomenology - The Philosophy TheDokument23 SeitenPhenomenology and Hermeneutic Phenomenology - The Philosophy TheShaira Mae YecpotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 Inductive VS Deductive ReasoningDokument8 SeitenChapter 3 Inductive VS Deductive ReasoningAngel Anne PadillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Induction Vs Deduction WRDokument3 SeitenInduction Vs Deduction WRAc MIgzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosopy Module 2, Grade 12 BezosDokument10 SeitenPhilosopy Module 2, Grade 12 Bezosadrian lozanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PhilosophyDokument17 SeitenPhilosophyAlex AnteneroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ryle On MindDokument1 SeiteRyle On MindAnna Sophia EbuenNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Lecture Delivered at The Department of Philosophy GadamerDokument22 SeitenA Lecture Delivered at The Department of Philosophy GadamerCaptainDavyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Img089 MergedDokument51 SeitenImg089 MergedWill MorrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding HypothesisDokument7 SeitenUnderstanding HypothesisSpencer ChristenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amnd Synthesis EssayDokument1 SeiteAmnd Synthesis Essayapi-302032867Noch keine Bewertungen

- Topic 6Dokument26 SeitenTopic 62021826386Noch keine Bewertungen

- I Know Lvl3, Ep5Dokument5 SeitenI Know Lvl3, Ep5Aymen BougueffaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gself-1 1Dokument3 SeitenGself-1 1Marjorie Balangue MacadaegNoch keine Bewertungen

- Martin Heidegger and The Question of Being: January 2017Dokument19 SeitenMartin Heidegger and The Question of Being: January 2017Volker HerreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inductive and Deductive ReasoningDokument16 SeitenInductive and Deductive ReasoningCedrick Nicolas Valera0% (1)