Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

S.6 What May Be Transferred

Hochgeladen von

Bharath SimhaReddyNaidu0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

29 Ansichten44 SeitenThis document discusses the application of Sections 6(a) and 43 of the Transfer of Property Act. Section 6(a) states that the chance of an heir succeeding to an estate or a relation obtaining a legacy cannot be transferred. Section 43 states that if a person fraudulently represents they are authorized to transfer property and later acquires an interest in the property, the transfer will be valid. The document examines a Supreme Court case and observes that Section 6(a) and 43 relate to different subjects and there is no conflict between them - Section 6(a) prohibits certain transfers while Section 43 creates an estoppel based on representation of title.

Originalbeschreibung:

JJ

Originaltitel

TPA 4

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PPTX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis document discusses the application of Sections 6(a) and 43 of the Transfer of Property Act. Section 6(a) states that the chance of an heir succeeding to an estate or a relation obtaining a legacy cannot be transferred. Section 43 states that if a person fraudulently represents they are authorized to transfer property and later acquires an interest in the property, the transfer will be valid. The document examines a Supreme Court case and observes that Section 6(a) and 43 relate to different subjects and there is no conflict between them - Section 6(a) prohibits certain transfers while Section 43 creates an estoppel based on representation of title.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PPTX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

29 Ansichten44 SeitenS.6 What May Be Transferred

Hochgeladen von

Bharath SimhaReddyNaiduThis document discusses the application of Sections 6(a) and 43 of the Transfer of Property Act. Section 6(a) states that the chance of an heir succeeding to an estate or a relation obtaining a legacy cannot be transferred. Section 43 states that if a person fraudulently represents they are authorized to transfer property and later acquires an interest in the property, the transfer will be valid. The document examines a Supreme Court case and observes that Section 6(a) and 43 relate to different subjects and there is no conflict between them - Section 6(a) prohibits certain transfers while Section 43 creates an estoppel based on representation of title.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PPTX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 44

S.

6 what may be transferred

Property of any kind may be transferred, except as otherwise

provided by this Act or by any other law for the time being in

force:

(a) The chance of an heir-apparent succeeding to an estate,

the chance of a relation obtaining a legacy on the death of a

kinsman, or

any other mere possibility of a like nature,

cannot be transferred.

Doctrine of spes successionis

The above shall be understood with S.60 of the CPC which

depicts of exclusions in the process of execution of decree or

order.

The things non-transferable under this clause

are:

(1) The chance of an heir succeeding to an

estate,

(2) The chance of a relation obtaining legacy (a

gift by will) on the death of a kinsman, and

(3) any other mere possibility of a like nature.

(winning a lottery or prize in a certain

competition), right to future offerings.

S.43 Transfer by an authorized

person who subsequently acquires

interest in property transferred

Where a person fraudulently or erroneously

represents that he is authorized to

transfer certain immovable property and

professes to transfer such property for consideration,

such transfer shall,

at the option of the transferee,

operate on any interest which the transferor may

acquire in such property at any time during which

the contract of transfer subsists.

Nothing in this section shall impair the right of

transferees in good faith for consideration

without notice of the existence of the said

option.

Illustration: A, a Hindu who has separated from

his father B, sells to C three fields, X, Y and Z,

representing that A is authorized to transfer the

same. Of these fields Z does not belong to A, it

having been retained by B on the partition; but

on B’s dying A as heir obtains Z. C, not having

rescinded the contract of sale, may require A to

deliver Z to him.

Essentials: (1) A fraudulent or erroneous

representation that the transferor had authority

.

to transfer the immovable property;

(2) The transfer is for consideration;

(3) The transferee subsequently acquires the

interest which he had professed to transfer, and

(4) At any time during which the contract of

transfer subsists.

This section shall not impair the right of

transferees in good faith for consideration

without notice of the existence of the said

option.

Transfer by unauthorized person.

Whether the transferor acts bona fide or

fraudulently or innocently.

Where the transferee does act on the

representation he will have the benefit of the

equitable doctrine u/s.43 however fraudulent

the act may be.

Feeding the grant of estoppel:

This works partly on the english doctrine that a

man who has promised more than what he can

perform, must make good his promise when he

acquires the power of performance.

Representation: The benefit of this section

cannot be claimed by the transferee if he did

not believe in or act upon it.

There is no estoppel when truth is known to

both the parties.

Transfer for consideration:

It is not applicable when the transfer is

gratuitous. By way of gift it is not applicable.

Transfer forbidden by law:

If it is invalid as being forbidden by law or

contrary to public policy.

IEA S.115 Estoppel:

When one person has,

by his declaration, act or omission,

intentionally caused or permitted another person to

believe a thing to be true and

to act upon such belief,

neither he nor his representatives shall be allowed,

in any suit or proceeding between himself and

such person or his representative,

to deny the truth of that thing.

Jumma Masjid, Mercara v.

Kodimaniandra Deviah (AIR1962 SC

847)

Santhappa Nanjudappa Basappa Mallammal

Ammakka Gangamma

Rameshgowda Malleshgowda

Basappa Mallappa Santhappa

Brief facts:

The facts are not in dispute.

There was a joint family consisting of 3

brothers, Santhappa, Nanjudappa and Basappa

and one sister, Mallammal.

Santhappa died unmarried. Basappa died in

1901, leaving behind a widow Gangamma.

Nanjudappa died in 1907 leaving his widow

Ammakka and she died in 1910.

The estate devolved on Basappa, Mallappa and

Santhappa as next reversioners.

By a sale deed Ex.III the three reversioners B, M

and S, sold the properties to one Ganapathi, under

whom respondents claim, for a consideration of

Rs.2000/- as they are the last male owners.

The vendor executed another deed, EX-IV

through which certain items of properties were

included.

On the strength of these two deeds, Ganapathi

sued to recover possession of the properties

comprised therein.

It was contested by Gangamma who claimed that

they were self acquisitions of her husband, and

that she, as his heir, was entitled to them. It was

accepted by the Trial Courts.

Gangamma died in February 17, 1933.

Thereupon Ganapathi applied to the Revenue

Authorities to transfer the patta for the lands

standing in the name of Gangamma to his own

name, in accordance with the sale deed Ex.III.

The appellant claimed that the ‘G’ has

transferred the property through a Gift on

dated Sep 5, 1932.

Secondly, under a deed of release executed by

Santhappa, one of the reversioners,

relinquishing his half-share in the properties to

the mosque for a consideration of Rs.300/- on

March,1933 through Ex-A

The Revenue authorities declined to accept the

title of the appellant and directed to give the

possession of the properties to Ganapathi.

Issue: The sole point for determination in this

appeal is:

whether a transfer of property for

consideration made by a person who

represents that he has a present and

transferable interest therein only a spes

successionis is within the protection of S.43 of

the TPA or not?

Observations

The claim made in the plaint is that as the

vendors had only a Spes successionis in the

properties during the lifetime of Gangamma, the

transfer was void and conferred and no title.

The defense argument was that as Santhappa had

sold the properties to Ganapathi on a

representation that he had become entitled to

them as reversioner of on the death of Ammakka.

So he was estopped from asserting that he had no

title at the dates of EX-III and EX-IV

Considering the scope of the S.43 of the TPA

“that it clearly applies whenever a person

transfers property to which he has no title on a

representation that he has a present and

transferable interest therein, and acting on that

representation, the transferee takes a transfer for

consideration”.

If the transferor subsequently acquires the

property, the transferee becomes entitled to it, if

the transferee has not cancelled the contract.

The contention on behalf of the appellant is

that S.43 must be read subject to S.6(a) of the

TPA which enacts that:

“The chance of an heir apparent succeeding to an

estate, the chance of a relation obtaining a legacy

on the death of a kinsman or any other mere

possibility of a like nature, cannot be transferred”.

The argument is that if S.43 is to be

interpreted that will have effect of nullifying

S.6(a), and that therefore it would be proper to

construe S.43 as limited to cases of transfers other

than those falling within S.6(a).

In effect, this argument involves importing into

the section a new exception to the following effect:

“Nothing in this section shall operate to confer on

the tranferee any title, if the transferor had at the

date of the transfer an interest of the kind

mentioned in S.6(a)”.

If we accede to this contention, we will not be

construing S.43, but rewriting it.

“We are not entitled”, observed Lord Loreburn

L.C., in Vickers v. Evans “to read words into an

Act of Parliament unless clear reason for it is to be

found within the four corners of the Act itself”.

Observations: If it is, then on the facts found by

the courts below, the title of the respondents

under Ex.III and Ex.IV must prevail over that

of the appellant under Ex-A.

The contention on behalf of the appellant is

that S.43 must be read subject to S.6(a) of the

TPA which enacts that :

“The chance of an heir apparent succeeding to

an estate, the chance of a relation obtaining a

legacy on the death of a kinsman or any other

mere possibility of a like nature, cannot be

transferred”.

The argument is that if S.43 is to be interpreted

as having application to cases of what is in fact

transfers of spes successionis, that will have the

effect of nullifying S.6(a), and that therefore it

would be proper to construe to s.43 as limited

to cases of transfers of other than those falling

within S.6(a).

If we accept this argument we are creating an

exception for S.43 through which we are not

construing the section rather we are rewriting

which “we are not entitled”.

S.6(a) and S.43 relate to two different subjects,

and there is no necessary conflict between them.

S.6(a) deals with certain kinds of interests in

property mentioned therein, and prohibits a

transfer simpliciter of those interests.

S.43 deals with representations as to title made by

a transferor who had no title at the time of

transfer and got the title subsequently.

S.6(a) enacts a rule of substantive law, while S.43

enacts a rule of estoppel which is one of evidence.

The two provisions operate on two different

fields, and different conditions, and we see no

ground for reading a conflict between them.

In our opinion, both of them can be given full effect

on their own terms, in their respective spheres.

It is also contended that as under the law there can

be no estoppel against a statute, transfers which are

prohibited by S.6(a) could not be held to be

protected by S.43.

Rules of estoppel are not to be restored for

defeating or circumventing prohibition enacted by

statutes on grounds of public policy.

The point for decision is simply whether on the

facts the respondents are entitled to the benefit of

this section.

The plea of estoppel raised by them on the terms of

the section is one pleaded under, and not against

the statute.

We shall now proceed to consider the more

important cases wherein the present question has

been considered.

One of the earliest case: Alamanaya Kunigari Nabi

Sab v. Murukuti Papiah (AIR 1915 Mad 972) that

arose out of a suit to enforce a mortgage executed

by the son over properties belonging to the father,

while he was alive.

The father died pending the suit, and the

properties devolved on the son as his heir.

The point for decision was whether the mortgagee

could claim the protection of S.43 of the TPA.

It was represented to the transferee that the

transferor was in praesenti entitled to and thus

authorise to transfer the property.

The official Assignee, Madras v. Sampath Naidu

(AIR 1933 Mad 795), where a different view was

taken.

The facts were that one V.Chetti had executed two

mortgages over properties in respect of which he had

only spes successionis.

Then he succeeded to those properties as heir and

then sold them to one Ananda Mohan.

A mortgagee claiming under Anand Mohan filed a

suit for a declaration that the two mortgages created

by Chetty before he had become entitled to them as

heir, were void as offending S.6(a) of TPA.

The Court negatived this contention and held that as

the mortgages, when executed, contravened S.6(a)

and they could not become valid u/s.43.

“The effect would be that by a clever description

of the property dealt with in a deed of transfer

one would be allowed to conceal the real nature

of the transaction and evade a clear statutory

prohibition”.

It is immaterial whether the transferor acts

bonafide or fraudulently in making the

representation.

It is only material to find out whether in fact the

transferee has been misled.

S.43 words were “where a person erroneously

represents” and now, as amended in 1929 they

are “where a person fraudulently or erroneously

represents”.

It does not matter in the cases of whether the transferor

acted fraudulently or innocently in making the

representation, what is material is that he did make a

representation and the transferee has acted on it.

Where the transferee knew as a fact that the transferor

did not possess the title which he represents he has,

then he cannot be said to have acted on it when taking

a transfer, then S.43 would have no application, and

the transfer will fail u/S.6(a).

But, where the transferee does act on the

representation, there is no reason why he should not

have the benefit of the equitable doctrine embodied in

S.43, however fraudulent the act of the transferor

might have been.

In our view Official Assignee, Madras case decision

was erroneous and rightly overruled subsequently

in the following case:

Shyam Narain v. Mangal Prasad (1935 ILR 57 All

474):

One Ram Narayan, who was the daughter’s son of

the last male owner, sold the properties in 1910 to

the Respondents, while they were vested in the

daughter, Akashi.

On her death in 1926, he succeeded to the properties

as heir and sold them in 1927 to the appellants.

The court held that although he was not having the

title at the time of the initial transfer however he

subsequently got the title then S.43 apply.

Before the contract of transfer comes to an end,

the transferor acquires an interest in that

property, no matter whether by private

purchase, gift, legacy or by inheritance or

otherwise, the previous transfer can at the option

of the transferee operate on the interest which

has been subsequently acquired, although it did

not exist at the time of the transfer.

Conclusion: we accordingly hold that when a

person transfers property representing that he

has a present interest therein, whereas he has, in

fact, only a spes successionis, the transferee is

entitled to the benefit of S.43, if he has taken the

transfer on the faith of that representation and

for consideration.

In the present case, Santhappa, the vendor in

Ex.III, represented that he was entitled to the

property in presenti, and it has been found that

the purchaser entered into the transaction

acting on that representation.

He, therefore acquired title to the properties

u/S.43 of the TPA, when Santhappa became in

titulo on the death of Gangamma on Feb 17,

1933, and the subsequent dealing with them by

Santhappa by way of release u/Ex.A did not

operate to vest any title in the appellant.

The appeal must be dismissed with costs.

Kartar Singh v. Harbans Kaur (1994) 4

SCC 730

Brief Facts:

Smt.Harbans Kaur – respondent executed the sale

deed in 1961, in favor of the appellant of alienating

the lands on her behalf and on behalf of her minor

son, Kulwant Singh.

He, after attaining majority filed a case in 1975 for a

declaration that the sale of his share in the lands

mentioned in the schedule attached thereto by his

mother was void and does not bind him.

The decree ultimately was granted declaring that

the sale was void as against the minor.

But, before taking deliver of the possession,

Kulwant Singh died.

She, the mother being the class I heir succeeded

to the estate of the deceased.

The appellant laid his claim to the benefit of

S.43 of the TPA, which was refused by the

High Court.

Thus these appeals by special leave.

Issues: Whether the S.43 of the TPA applies to

protect the rights on the property of the

appellant or not?

Observations:

The contention for the appellant is that in view

of the finding that Harbans Kaur had

succeeded by operation of law, hence he is

entitled to the interest acquired by her by

operation of S.43 of the Act and the H.C has

misapplied the ratio of decisions of this Court

in Jumma Masjid, Mercara case, instead it

would have applied the decision of the Patna

H.C. in Jhulan Prasad v. Ram Raj Prasad (AIR

1979 Pat 54).

To apply S.43 two conditions must be satisfied.

1. There is a fraudulent or erroneous

representation made by the transferor to the

transferee that he is authorized to transfer

certain immovable property and in the

purported exercise of authority, professed to

transfer such property for consideration.

2. When it is discovered that the transferor

acquired an interest in the transferred property,

at the option of the transferee, he entitled to get

the restitution of interest in property got by the

transferor, provided the transferor acquires such

interest in the property during which contract of

transfer must subsist.

In this case, admittedly, Kulwant Singh was a minor

on the date of the transfer. The marginal note of the

sale deed specifically mentions to the effect:

“….that the land had been acquired by her and by her

minor son by exercising the right of pre-emption and

that she was executing the sale deed in respect of her

own share and acting as guardian of her minor son so

far as his share was concerned”.

It is settled law that the transferee must make all

reasonable and diligent enquiries regarding the capacity

of the transferor and the necessity to alienate the estate

of the minor.

On satisfying those requirements, he is to enter and

have the sale deed from the guardian or manager of the

estate of the minor.

Under the Guardian and Wards Act, the estate of

the minor cannot be alienated unless a specific

permission in that behalf is obtained from the

district Court.

Admittedly, no such permission was obtained.

Therefore, the sale of the half share of the interest

of Kulwant Singh made by his mother is void.

S.43 feeds its estoppel.

The rule of estoppel by deed by the transferor

would apply only when the transferee has been

misled.

The transferee must know or put on notice that the

transferor does not possess the title which he

represents that he has.

As a reasonable prudent man the appellant is

expected to enquire whether on her own the

mother as guardian of minor son is competent

to alienate the estate of the minor.

When such acts were not done the first limb of

S.43 is not satisfied.

It is obvious that it may be an erroneous

representation and may not be fraudulent one

made by the mother that she is entitled to

alienate the estate of the minor.

For the purpose of S.43 it is not strong material

for consideration.

On declaration that the sale is void, in the eye

of law the contract is non est to the extent of the

share of the minor from its inception.

The second limb of S.43 is that the contract

must be a subsisting one at the time of the

claim.

A void contract is no contract in the eye of law

and was never in existence, hence second limb

of this section is not satisfied.

Conclusion: In the face of the existence of the

aforementioned note and in the light of the

law, it could be concluded that S.43 does not

apply to the facts of this case.

The ratio of the Patna H.C. also does not apply

the facts in this case as rightly distinguished by

the H.C.

It is made clear that the declaration given by

the H.C. is only qua the right of the minor and

it is fairly conceded by the respondent that the

decree does not have any effect on the half

share conveyed by the mother.

If the appellant has any independent cause of

action subsisting under the contract against the

respondent, this judgment may not stand in

this way to pursue the remedy under the law.

The appeals are accordingly dismissed.

S.6(b) A mere right of re-entry for breach of a

condition subsequent cannot be transferred to any

one except the owner of the property affected

thereby;

(b) Right of re-entry: In leases if the rents are in

arrears or breach of covenants in the lease but the

transfer of land is allowed.

A mere right of re-entry for breach of a condition

subsequent to the grant of the lease cannot be

transferred.

An option to sell the property is valid under the

law and the assignee can enforce the performance

against the vendee and the vendee cannot plead

the absence of privity of contract.

S.6(c) An easement cannot be transferred apart

from dominant heritage.

Examples are rights of way, rights of water, rights

of light etc.,

S.4 of the Easement Act, 1882 defines the Easment:

“an easement is a right which the owner or

occupier of certain land possesses as such for the

beneficial enjoyment of land,

to do and continue to do something, or

to prevent and to continue to prevent something

being done,

in or upon or in respect of,

certain other land which is not his own”.

S.6(d). All interest in property restricted in its

enjoyment to the owner personally cannot be

transferred by him.

Eg., lease, a religious office, a right of pre-

emption, after the partition the brothers should

have priority in buying the property

S.6(dd) Right to future maintenance: The

objective of maintenance is that a person

unable to maintain himself or herself should

not be left destitute and should be prevented

from being in a state of vagrancy. If it is

allowed then its very object will be defeated.

Clause (e): Mere right to sue: damages for

breach of contract, or for tort. The object is to

prevent gambling in litigation. Right to sue is

personal to the party aggrieved.

Clause(f): Public Office cannot be transferred.

This prohibition works on public policy. The

salary of a public officer is not transferable,

although u/s.60 of CPC it is attachable with

certain limits.

Clause(g): Pensions: To Military and civil

pensioners of Government and political

pensions cannot be transferred. These are given

for the past services rendered.

Clause(h): Nature of interest cannot be transferred.

Such as services of inam etc.,

(ii) U/S 23 of the ICA, a consideration or object is

unlawful if it is

(1) forbidden by law; or

(2) is of such nature that it defeats the provisions of

any law; or

(3) is fraudulent; or

(4) involves or implies injury to the person or

property of another; or (adoption given for

consideration)

(5) or the course regard it as immoral or

(6) opposed to public policy.

(iii) Disqualified to be a transferee: S.136,O21

r73.

Clause(i): Untransferable right of occupancy.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Law of ContractDokument20 SeitenLaw of ContractTeena Poonacha100% (1)

- Raj Kumar Mohan Singh v. Raj Kumar Pasupathinath Saran, 1969 AIR 135 1969 SCR (1) 1Dokument14 SeitenRaj Kumar Mohan Singh v. Raj Kumar Pasupathinath Saran, 1969 AIR 135 1969 SCR (1) 1Srishti Jain100% (1)

- Wills Succession Atty. Sebastian Lecture NotesDokument71 SeitenWills Succession Atty. Sebastian Lecture Notesroa yusonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Testacy of Maxima Santos v. Flora BlasDokument4 SeitenTestacy of Maxima Santos v. Flora BlasJm Santos50% (2)

- Latin Legal Phrases, Terms and Maxims as Applied by the Malaysian CourtsVon EverandLatin Legal Phrases, Terms and Maxims as Applied by the Malaysian CourtsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Housekeeping Services Agreement (With Tracked Changes)Dokument56 SeitenHousekeeping Services Agreement (With Tracked Changes)Anonymous WS9qAgwJvNoch keine Bewertungen

- S.6 What May Be Transferred: Spes SuccessionisDokument42 SeitenS.6 What May Be Transferred: Spes SuccessionisBhanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Property of Any Kind May Be TransferredDokument42 SeitenProperty of Any Kind May Be TransferredDileep ChowdaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule of Feeding The Grant by Estoppels (Section 43)Dokument11 SeitenRule of Feeding The Grant by Estoppels (Section 43)AN HadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Property Law Project: Submitted byDokument8 SeitenProperty Law Project: Submitted bypriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer by Unauthorised Person Who Subsequently Acquires Interest in Property Transferred (S.43)Dokument8 SeitenTransfer by Unauthorised Person Who Subsequently Acquires Interest in Property Transferred (S.43)samNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analyse The Case of Jumma Masjid V K. Deviah (AIR 1962 SC 847)Dokument3 SeitenAnalyse The Case of Jumma Masjid V K. Deviah (AIR 1962 SC 847)Shweta SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section 6 of The Transfer of Property Act, 1882Dokument8 SeitenSection 6 of The Transfer of Property Act, 1882Harshat SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difference Between Section 6 (A) AND 43Dokument21 SeitenDifference Between Section 6 (A) AND 43SUNNY BHATIANoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Comment "Jumma Masjid, Mercara vs. Kodimaniandra Deviah, AIR 1962 SC 847"Dokument2 SeitenCase Comment "Jumma Masjid, Mercara vs. Kodimaniandra Deviah, AIR 1962 SC 847"Deepa Saroj100% (1)

- Anoushka 1856 Semester Iv Law of Property, Equity and TrustDokument14 SeitenAnoushka 1856 Semester Iv Law of Property, Equity and TrustHashir KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- FATHEHDokument6 SeitenFATHEHShreeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Property LawDokument16 SeitenProperty LawGulafshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ownership by Estoppel Under Transfer of Property ActDokument6 SeitenOwnership by Estoppel Under Transfer of Property ActAashish GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, LucknowDokument16 SeitenDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, LucknowkakuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer of Property Act AssignmentDokument11 SeitenTransfer of Property Act Assignmentnihit mishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer of Property ActDokument8 SeitenTransfer of Property ActJyoti MauryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter - 1: 1.1 Research MethodologyDokument8 SeitenChapter - 1: 1.1 Research MethodologyKapildev Dhaka100% (14)

- Property Law - 20010125408 - Harshat SinghDokument8 SeitenProperty Law - 20010125408 - Harshat SinghHarshat SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Probables - SuccessionDokument54 SeitenBar Probables - SuccessionPop CatalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer by Unauthorised Person Who Subsequently Acquires Interest in Property TransferredDokument4 SeitenTransfer by Unauthorised Person Who Subsequently Acquires Interest in Property TransferredShashikant SauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- What May Be Transferred (S.6) Property of Any KindDokument15 SeitenWhat May Be Transferred (S.6) Property of Any KindsamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section 6Dokument6 SeitenSection 6Nitya DaryananiNoch keine Bewertungen

- TPA End SemDokument6 SeitenTPA End SemHarshV.PandeyANsh100% (1)

- TPA CA2 NotesDokument16 SeitenTPA CA2 NotesSharad panwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, LucknowDokument7 SeitenDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, LucknowyashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palacios Vs RamirezDokument6 SeitenPalacios Vs RamirezIvan Montealegre ConchasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Succession DigestDokument5 SeitenSuccession DigestGigiRuizTicarNoch keine Bewertungen

- BONILLA V. BARCENA (G.R. No. L-41715 June 18, 1976, 71 SCRA 491)Dokument3 SeitenBONILLA V. BARCENA (G.R. No. L-41715 June 18, 1976, 71 SCRA 491)MhareyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Declaratory DecreeDokument8 SeitenDeclaratory DecreeLovepreet 08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cases For Wills and Succession CompilationDokument113 SeitenCases For Wills and Succession CompilationRaffy LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lykins v. McGrath, 184 U.S. 169 (1902)Dokument4 SeitenLykins v. McGrath, 184 U.S. 169 (1902)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ada Vs BaylonDokument3 SeitenAda Vs BaylonMA. TRISHA RAMENTONoch keine Bewertungen

- 8.de Mesa v. MenciasDokument2 Seiten8.de Mesa v. MenciasKate Bianca CaindoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Succession 1Dokument48 SeitenSuccession 1pandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smith BellDokument71 SeitenSmith BellRegina AsejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solis v. Barroso (53 Phil 912)Dokument2 SeitenSolis v. Barroso (53 Phil 912)Maria TalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feeding Grant by EstoppelDokument4 SeitenFeeding Grant by EstoppelollypocosrNoch keine Bewertungen

- NOTES 1 Aug 2020Dokument15 SeitenNOTES 1 Aug 2020Jolo EspinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- NOTES 1 Aug 2020Dokument15 SeitenNOTES 1 Aug 2020Jolo EspinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisologo Vs SingsonDokument5 SeitenCrisologo Vs SingsonIvan Montealegre ConchasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shri Ram Janam Bhoomi Ayodhya Verdict Part 9 of 14Dokument500 SeitenShri Ram Janam Bhoomi Ayodhya Verdict Part 9 of 14satyabhashnamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 16Dokument16 SeitenSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 16lathacoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Borromeo Vs BorromeoDokument3 Seiten5 Borromeo Vs BorromeoRojan Alexei GranadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Succession - Civil Law Review Final PDFDokument33 SeitenSuccession - Civil Law Review Final PDFjpoy61494Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assig NmenDokument6 SeitenAssig NmenSHAHZADNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spes Successionis As An Exception To Transferability - Legal News - Law News & Articles - Free Legal Helpline - Legal Tips - Legal IndiaDokument10 SeitenSpes Successionis As An Exception To Transferability - Legal News - Law News & Articles - Free Legal Helpline - Legal Tips - Legal Indiasiddharth pandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Succession Case DigestsDokument30 SeitenSuccession Case DigestsRegine Yamas100% (2)

- Crisologo V SingsonDokument2 SeitenCrisologo V SingsonJasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Duran Vs IACDokument3 SeitenDuran Vs IACClaudine SumalinogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Substitution by The HeirsDokument10 SeitenSubstitution by The HeirsFrancesco Celestial BritanicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 RAMIREZ vs. RAMIREZ (Usufructuary)Dokument4 Seiten1 RAMIREZ vs. RAMIREZ (Usufructuary)Robert EspinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rallos V FelixDokument4 SeitenRallos V FelixJohn Leo BawalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Property Law CasesDokument8 SeitenProperty Law CasesRamanah VNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Science of Happiness: ‘Discovering the Secrets of a Joyful and Fulfilling Life’Von EverandThe Science of Happiness: ‘Discovering the Secrets of a Joyful and Fulfilling Life’Noch keine Bewertungen

- Constitution of the State of Minnesota — 1964 VersionVon EverandConstitution of the State of Minnesota — 1964 VersionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National LAW Univer Sity Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDokument28 SeitenDamodaram Sanjivayya National LAW Univer Sity Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National LAW Universit Y Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDokument59 SeitenDamodaram Sanjivayya National LAW Universit Y Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application of International Environmental Law in Outer SpaceDokument13 SeitenApplication of International Environmental Law in Outer SpaceBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air and Space LawDokument52 SeitenAir and Space LawBharath SimhaReddyNaidu100% (1)

- Icl 2015022Dokument20 SeitenIcl 2015022Bharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOPIC: Extradition Law: Indian Perspective: Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDokument20 SeitenTOPIC: Extradition Law: Indian Perspective: Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Space Law 2015022Dokument23 SeitenSpace Law 2015022Bharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

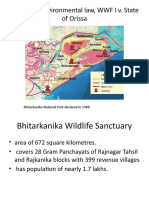

- Wildlife Protection ActDokument15 SeitenWildlife Protection ActBharath SimhaReddyNaidu100% (1)

- TOPIC: Extradition Law: Indian Perspective: Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDokument15 SeitenTOPIC: Extradition Law: Indian Perspective: Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wildlife CaseDokument10 SeitenWildlife CaseBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women and Law FINALDokument50 SeitenWomen and Law FINALBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Today CallsDokument1 SeiteToday CallsBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Analysis of Affirmative Action in India and U.S.ADokument32 SeitenComparative Analysis of Affirmative Action in India and U.S.ABharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forest Rights ActDokument22 SeitenForest Rights ActBharath SimhaReddyNaidu100% (1)

- TOPIC: Jurisdiction and Admissibility of International Criminal CourtDokument25 SeitenTOPIC: Jurisdiction and Admissibility of International Criminal CourtBharath SimhaReddyNaidu0% (1)

- Law & AgricultureDokument43 SeitenLaw & AgricultureBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOPIC - Analysis of Anti Competitive AgreementsDokument25 SeitenTOPIC - Analysis of Anti Competitive AgreementsBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law & Agriculture 1Dokument43 SeitenLaw & Agriculture 1Bharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Search Seizure Income Tax ActDokument89 SeitenSearch Seizure Income Tax ActBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDokument29 SeitenDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW - Unit 1Dokument57 SeitenPRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW - Unit 1Bharath SimhaReddyNaidu100% (2)

- Section 9 of Income Tax Act 1961Dokument55 SeitenSection 9 of Income Tax Act 1961Bharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- DIVORCEDokument34 SeitenDIVORCEBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legitimate and IllegitimateDokument25 SeitenLegitimate and IllegitimateBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Settlement Commission: Dr. P. Sree Sudha, LL.D Associate ProfessorDokument20 SeitenSettlement Commission: Dr. P. Sree Sudha, LL.D Associate ProfessorBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answer The FollowingDokument1 SeiteAnswer The FollowingBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- JURISDICTIONDokument42 SeitenJURISDICTIONBharath SimhaReddyNaiduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Falcon Complaint $50 MillionDokument25 SeitenFalcon Complaint $50 MillionScottNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rfo Flexi Financing Option: Manchester 1Dokument3 SeitenRfo Flexi Financing Option: Manchester 1ninopnatividadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mortgage Need To Send Mortgagelender-Licensee-Download-09302017Dokument108 SeitenMortgage Need To Send Mortgagelender-Licensee-Download-09302017Chris TylerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Youtube Account Transfer AgreementDokument4 SeitenYoutube Account Transfer AgreementEmmanuel Emeka EkemedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reko-Diq CaseDokument2 SeitenReko-Diq Casemohammad faraz aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environment, Transport and Works Bureau Technical Circular (Works) No. 3/2005 Novation of Consultancy AgreementsDokument16 SeitenEnvironment, Transport and Works Bureau Technical Circular (Works) No. 3/2005 Novation of Consultancy AgreementsJacky_LEOLEONoch keine Bewertungen

- Georgetown - Foreign IBEL Curriculum Guide 2014Dokument8 SeitenGeorgetown - Foreign IBEL Curriculum Guide 2014electronionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporation v. Allied Banking Corpora Tion (G.R. No. 187922, September 21, 2016) - YB Is Not ADokument19 SeitenCorporation v. Allied Banking Corpora Tion (G.R. No. 187922, September 21, 2016) - YB Is Not ALaarni GeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perlindungan Hukum Bagi Penjamin Dalam Perjanjian Penanggungan (Borgtocht) Di PT Bank Negara Indonesia (Persero) TBKDokument21 SeitenPerlindungan Hukum Bagi Penjamin Dalam Perjanjian Penanggungan (Borgtocht) Di PT Bank Negara Indonesia (Persero) TBKWahyu DelftStraightNoch keine Bewertungen

- WTO - Intellectual Property - Overview of TRIPS AgreementDokument9 SeitenWTO - Intellectual Property - Overview of TRIPS AgreementDr. Mohd. Aamir KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contoh NdaDokument4 SeitenContoh Ndaiqbal kamilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law of ContractDokument10 SeitenLaw of ContractNur Batrishya IsmailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 1784 To 1809Dokument4 SeitenArticle 1784 To 1809BB KINGNoch keine Bewertungen

- TPA - Important SectionsDokument2 SeitenTPA - Important SectionsRitesh AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 3 - SECTION 5 Divisible and Indivisible Obligations 1223-1225 318-323Dokument4 SeitenCHAPTER 3 - SECTION 5 Divisible and Indivisible Obligations 1223-1225 318-323LawStudent101412100% (1)

- Código Civil CaliforniaDokument10 SeitenCódigo Civil CaliforniaCarla PieriniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Trademark Law 1. Trademark, Servicemarks & Trade NameDokument5 SeitenPhilippine Trademark Law 1. Trademark, Servicemarks & Trade NameDenise GordonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 9 Contracts in ParticularDokument5 SeitenUnit 9 Contracts in ParticularÁlvaro Vacas González de EchávarriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Font LicenseDokument2 SeitenFont LicenseDarmawan PangaribuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bobcat Loader t595 Hydraulic Electrical SchematicDokument8 SeitenBobcat Loader t595 Hydraulic Electrical Schematicvictorbooth231093jbg100% (66)

- Special Power of Attorney - Lease ContractDokument2 SeitenSpecial Power of Attorney - Lease Contractphoebemariealhambra1475100% (1)

- Association LTD, The Supreme Court Provided That The Articles ofDokument21 SeitenAssociation LTD, The Supreme Court Provided That The Articles ofAman BajajNoch keine Bewertungen

- 110 Valencia V CA GR 122363 DDokument2 Seiten110 Valencia V CA GR 122363 DDeniseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 - Lesson 2Dokument10 SeitenChapter 1 - Lesson 2John Irvin M. AbatayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 1 First Midterm PPPDokument30 SeitenGroup 1 First Midterm PPPAngelo BaguioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yngson Vs PNBDokument5 SeitenYngson Vs PNByzarvelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Guarantees ActDokument2 SeitenConsumer Guarantees ActHanna Christelle HoNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is A Mortgage DeedDokument2 SeitenWhat Is A Mortgage DeedAdan HoodaNoch keine Bewertungen